ABSTRACT

Charismatic organisms are often used as symbols of nature-based community development. Understanding value perceptions of ecosystems services provided by symbolic species is important because such perceptions often influence land management and cultural associations between people and nature. Here, we aimed to characterize local perceptions of social values for ecosystem services of wild cherries in Sakuragawa city, Japan. The city has long been renowned for the beautiful traditional landscape of its flowering wild cherries and is involved in various conservation activities as a part of regional planning. We administered a questionnaire survey to three socio-cultural groups: local residents, tourists, and high school students; their responses were analyzed by using SolVES. Value perceptions of ecosystem services provided by wild cherries differed considerably among these groups. The residents and tourists ranked the value ‘aesthetic in spring’ as highest, whereas high school students ranked many values equally. In addition, most of the students confused wild cherry trees with the popular cultivar ‘Somei-yoshino’. The students’ more limited knowledge of wild cherries may have affected their value perceptions. Looking at the spatial distribution of perceived values, local residents and tourists highly valued the specific sites famous for their wild cherry scenery. In contrast, students did not value such sites and perceived more value in urbanized areas. Although symbolic species help to develop the perceived value of nature, filling a knowledge gap and sharing a variety of values within local communities is important for promoting community-based management of traditional forest landscapes characterized by wild cherries.

Edited By:

1. Introduction

Focusing on the species that draw people’s attention is an effective approach in nature conservation (Bowen-Jones and Entwistle Citation2002; Home et al. Citation2009; Jepson and Barua Citation2015). Charismatic organisms, such as plants with beautiful flowers or large mammals with impressive behavior, are often used to capture the imagination of the public and raise funds for saving endangered species (Primack Citation2014; Bennett et al. Citation2015). Such concepts can be applied not only to conserving a specific threatened species but also to promoting nature-based community development. For example, edelweiss (Leontopodium nivale (Ten.) Huet ex Hand.-Mazz.) is a strong icon of alpinism in the European Alps and is used to support a wide range of cultural and economic activities (Grabherr Citation2009; Rüdisser et al. Citation2019). Silver fern (Cyathea dealbata (G. Forster) Swartz) is a national symbol of New Zealand, where an extremely large number of fern species occur (Department of Conservation, New Zealand Citation2021). In these cases, the species do not have to be endangered. In fact, they may be rather common or widely used by the public, which helps to stimulate people’s interest in local natural environments (Garibaldi and Turner Citation2004).

Symbolic species enhance people’s cultural associations with nature (Schirpke et al. Citation2018; Rüdisser et al. Citation2019), but perceptions of the species’ values are known to vary among social groups. In general, local value perceptions of nature and its ecosystem services are markedly different among individuals depending on their place of origin (Orenstein and Groner Citation2014; Moutouama et al. Citation2019; García-Llorente et al. Citation2020), socio-economic background (Sodhi et al. Citation2009; Muhamad et al. Citation2014; Shoyama and Yamagata Citation2016), and knowledge of and experiences with nature (Lamarque et al. Citation2011). In an investigation of people’s perception of street trees, Graça et al. (Citation2018) reported that their value perceptions were related to educational level and age. In a study of urban trees in South Africa, perceptions of the benefits of trees were clearly different based on residents’ income and place of residence (Shackleton et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, people’s use and perceptions of ecosystem service benefits were markedly different among forests with different histories and structures (Abram et al. Citation2014). Understanding the socio-cultural and environmental contexts of people’s value perceptions is critical for maintaining relationships between humans and nature as well as for transitioning to more sustainable societies (Chan et al. Citation2016; Pascual et al. Citation2017; Stålhammar Citation2021). In addition, identifying local people’s dependency on ecosystem services could serve as a basis of community-based landscape management (Plieninger et al. Citation2015). Nevertheless, it can be difficult to present how people perceive nature’s values, and the topic is often overlooked in decision-making (Schröter et al. Citation2014; Cheng et al. Citation2019; Sherrouse et al. Citation2022). This may lead to conflicts among stakeholders (García-Nieto et al. Citation2015; Zoderer et al. Citation2019) because ecosystem services usually have trade-offs (Bennett et al., Citation2009), so that prioritizing one ecosystem service could reduce another.

Cherry, or ‘Sakura’, is an important tree group in Japan. The trees are loved by many as a symbol of spring (Katsuki Citation2015; Konta Citation2016; Moriuchi and Basil Citation2019) (). The Japanese people have been familiar with cherry blossoms since ancient times. In Manyoshu, an anthology of poetry published in the 7th and 8th centuries in Japan, wild cherries are praised many times for their beauty. Moreover, wild cherries appeared frequently in ancient writings, plays, arts, and festivals (Sato Citation2005; Primack et al. Citation2009; Sakurai et al. Citation2011; Katsuki Citation2015). Thus, in Japan, wild cherries have a unique significance in supporting relationships between humans and nature.

Figure 1. Comparisons of cherry blossom trees in Japan. (a) Common cultivar (Cerasus × yedoensis (Matsum.) Masam. et Suzuki) planted along a street in Tsukuba city, Japan. (b) Wild cherry blossoms (Cerasus jamasakura (Siebold ex Koidz.) H. Ohba and Cerasus leveilleana (Koehne) H. Ohba) in Sakuragawa city, Japan. Left: A natural forest landscape in Hirasawa. Right: Planted trees in Isobe, which was designated as a National Place of Scenic Beauty and a National Monument by the Agency for Cultural Affairs.

Wild cherries tend to regenerate vigorously after forest disturbances in mountains and semi-natural ecosystems like Satoyama (Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute Citation2010; Katsuda et al. Citation2020). Satoyama is a socio-ecological production landscape consisting of secondary forests, agricultural fields, grasslands, and local communities. In Satoyama, people historically utilized natural resources for their living, and their management incidentally created favorable habitats for many plants and animals. Owing to this mutually beneficial relationship between humans and nature, Satoyama is expected to contribute to global goals for biodiversity conservation (Scheyvens et al. Citation2019). Popular for more than 1000 years in Japan, Satoyama forest management involved short-rotation harvesting (Takeuchi Citation2001; Washitani Citation2001). This practice gave wild cherry trees an advantage in regeneration. After the fuel revolution and widespread use of chemical fertilizers in the 1960s and 1970s, however, Satoyama forests were gradually abandoned (Hattori et al. Citation1995). Because of this social change, wild cherries are declining in many parts of Japan (Yamamoto and Takahashi Citation1991; Ishii and Nakagoshi Citation1997; Nakamura and Shigematsu Citation2000; Fujii et al. Citation2009).

Sakuragawa (), a suburban city in Ibaraki prefecture, Japan, designated wild cherries as a symbol for the promotion of local development (Sakuragawa City Government Citation2019). The city has long been renowned for the beautiful scenery of its wild cherry trees, Cerasus jamasakura (Siebold ex Koidz.) H. Ohba and Cerasus leveilleana (Koehne) H. Ohba. To conserve its forest landscapes of wild cherries, the Sakuragawa city government is involved in both forest management and environmental education. To make these efforts more effective and to improve decision-making regarding the promotion of community-based forest management, it is important to understand people’s diverse value perceptions of wild cherries and the ecosystem services they provide.

Figure 2. Map of Japan and inset of Sakuragawa city in Ibaraki prefecture showing the major geographic features and land uses.

In this study, we aimed to investigate people’s awareness of wild cherries and the perceived social values of their ecosystem services. Specific objectives were to characterize value perceptions of ecosystem services provided by wild cherry blossoms, analyze differences in local people’s perceptions, and identify factors affecting their perceptions. We conducted a questionnaire survey and analyzed responses by using Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES; Sherrouse et al. Citation2011, Citation2022), an open-source GIS tool developed for the analysis of people’s perceptions of social values for ecosystem services. In the analyses, we focused on three socio-cultural groups: local adult residents, tourists, and high school students. Local residents who live near the famous scenic sites of wild cherries can play a significant role in conservation efforts because some actively participate in trail maintenance and deliver information about wild cherries to the public. The tourists who visit Sakuragawa city to enjoy the beautiful scenery of wild cherries are likely interested in conservation of the trees, but their value perceptions may be different from those of local residents. With regard to high school students, the population of Sakuragawa city is aging, as seen in other rural districts in Japan. Thus, encouraging younger generations to become involved in management activities is a key to the success of conservation efforts.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area

The research was conducted in Sakuragawa city in western Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan (). In the eastern part of the city, the Tsukuba Mountain Range (elevation, 16–852 m) extends from north to south. The mean annual temperature and precipitation for the period 2002–2019 were 14.2°C and 1205 mm, respectively (Japan Meteorological Agency Citation2021). The study area is mostly within the warm-temperate evergreen forest zone at lower elevations and the cool-temperate deciduous forest zone at higher elevations. During the Meiji period (1868–1912), the low-elevation areas of the Tsukuba Mountain Range were covered by pine forests, oak forests, and secondary grasslands (Ogura Citation2019). These forests and grasslands were used by local residents to obtain natural resources, such as firewood, charcoal, and natural fertilizer, as typically seen in Satoyama ecosystems. In Sakuragawa city, there are many scenic areas with wild cherries. Among them, particularly famous are the Hirasawa and Isobe districts (). Hirasawa district is located in the foothill of Takamine hilly area and is famous for its natural forest landscape with wild cherries. In Isobe, many wild cherry trees were planted at a park-like flat area near Isobe shrine, and the site has been designated a National Place of Scenic Beauty and a National Monument by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Many people visit these sites every spring, averaging about 20,000 visitors each year (Sakuragawa City Government, personal communication). The city promotes community-based forest management in a Satoyama ecosystem, using wild cherries as a symbolic species to encourage public involvement.

2.2. Data collection

From April to November 2020, we administered a questionnaire survey to 321 participants (161 males, 152 females, and 8 who did not answer) in three groups: residents, tourists, and high school students. This questionnaire survey was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the University of Tsukuba (no. 2019–4). For the resident group, we mailed a questionnaire to each of the 184 residences in Hirasawa and Isobe districts; we received responses from 73 (ca. 40%) residences. For the tourist group, we performed face-to-face surveys with 70 visitors to the Sakura festival in Sakuragawa city (April 1–11, 2020). In the survey of tourists, one or two investigators talked to visitors and provided the survey sheets to those who agreed to participate. For the group of high school students, face-to-face surveys were conducted with 178 students from three of the four high schools in the city, for which we obtained permission from the high school administrators and/or instructors. Approximately 80% of the students were in their second year of high school (i.e. 16–17 years old). Although we combined mail (for residents) and face-to-face surveys (tourists and students), all participants received the same questionnaire sheet with detailed instructions (Appendix 1). Thus, we assumed that different administration methods had limited effects on the answers, but responses received from residents may represent individuals who were more motivated toward wild cherry conservation than non-respondents.

The main structure of the questionnaire was developed following Shoyama and Yamagata (Citation2016) and Riper et al. (Citation2017) (Appendix 1). The survey consists of three basic sections. Section Q1 inquired about the respondents’ attributes including gender and age, occupation, location of residence, and frequency of activities that involve contact with nature in their daily life. In Section Q2, respondents were asked about the frequency of cherry blossom viewing asked about their preference between the most popular cultivar C. × yedoensis and wild cherries and the types of conservation activities they are interested in, and asked to describe Satoyama. Respondents were shown two photographs of well-known scenic sites one was a natural forest landscape in Hirasawa, and the other was planted wild cherries in Isobe (; Appendix 1); they were then asked to select the one closer to their image of wild cherries. We then investigated whether respondents prefer wild cherries (C. jamasakura and C. leveilleana) compared to the most popular cultivar, C. × yedoensis. Most cherry trees planted in parks and along roadsides in Japan today are C. × yedoensis (Matsum.) Masam. et Suzuki ‘Somei-yoshino’. Cerasus × yedoensis is a cultivated variety created in the Edo period (1603–1864; see ). Before this cultivar was developed, wild cherry trees, such as C. jamasakura and C. leveilleana, were the representative cherries to the Japanese people (). The final question evaluated the degree of understanding of Satoyama, because wild cherry conservation in Sakuragawa city has a strong relationship with traditional Satoyama management (Katsuda et al. Citation2020). Respondents were asked to describe what they imagined when they heard the word Satoyama; those who gave answers like ‘a place that is rich in nature in the countryside’ and ‘a space where people and nature coexist in harmony’ were counted as understanding the term. In Section Q3, respondents were asked which of the following eight values of ecosystem services provided by wild cherries they perceive to be important: history, recreation, economy, aesthetic in spring, aesthetic in fall, biodiversity, education, and culture. For the selection of these values, we referred to the classification of social values of ecosystem services presented by Sherrouse et al. (Citation2011, Citation2022), that is, the definitions of social-value types provided in our main analytical tool, SolVES, and chose ones that appeared to have relatively direct relationships with a symbolic species. The value of culture was explained as a source of cultural and local identity of Sakuragawa city. Respondents were then asked to assign a number from 0% to 100% according to the degree of importance of each value, with the eight values summing to 100%. In addition, the respondents were asked to mark on a map of Sakuragawa city where they felt the values were assigned and to write the name of specific locations or landmarks associated with selected values, to the best of their knowledge.

2.3. Data analysis

For questions about the frequency of outdoor recreation, people’s awareness of wild cherries, and the trees’ perceived social values, a χ2 test was performed to analyze the statistical differences in answers among the three groups. Residual analysis was used to estimate the choices with significantly higher or lower response rates. In the analyses of perceived social values, we examined whether the eight values were equally distributed in each of the groups by using a goodness-of-fit test.

For the question regarding mapping of value types, we used SolVES (Sherrouse et al. Citation2011, Citation2022) to analyze the spatial distribution of respondents’ perceived social value of ecosystem services provided by wild cherries. After the data collection, a spatial database was developed from the digitized survey points obtained from the questionnaire. Each survey point and its associated data were digitized as a GIS point data along with the respondent’s ID, group, and locality names. In SolVES, users are able to input ‘attitude types’ regarding specific questions that the users arbitrarily selected. We did not use this function and simply compared the spatial patterns of perceived values among the three survey groups. We assigned the entirety of Sakuragawa city as the ‘study area’. The eight values described above were input as ‘value types’. After preparing these data, we constructed a geodatabase file consisting of multiple shapefiles and environmental layers for each of the three groups according to the user manual of SolVES version 3.0 (Sherrouse and Semmens Citation2015).

The values that people perceive from wild cherries were mapped using the Maximum Entropy Modeling Software (Maxent; Phillips et al. Citation2006) that was integrated into SolVES. Maxent models species’ niches and distributions by using a machine-learning technique, and it was applied to predict the distributions of social values of ecosystem services in SolVES. In the analysis with Maxent, the dependent variable is the grid-weighted value assigned by the respondents to each ecosystem service, and a 100 m-resolution raster dataset was prepared for the explanatory variables. The environmental metrics included elevation, slope, land-use type, vegetation type, distance to road, distance to water, distance to tourism resources, and distance to forest. Land-use type and vegetation type are categorical variables, whereas the others are continuous. In selecting these variables, we hypothesized that these factors affect local perceptions of social values for ecosystem services provided by wild cherries, but the size of effects may differ among groups. The environmental metrics data were obtained from the National Land Numerical Information Database (https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj/index.html) and Conservation GIS-Consortium Japan (http://cgisj.jp/about.html). Distance to road, distance to water, distance to tourism resources, and distance to forest were estimated with the Euclidean distance tool included in the ArcGIS Spatial Analyst. In addition, we examined the degree of clustering of point data for each value for ecosystem services by calculating average nearest neighbor statistics. These analyses were carried out using ArcGIS ver. 10.2 (Esri, Redlands, California).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of respondents

In the questionnaire survey, we obtained responses from 73 residents, 70 tourists, and 178 high school students. Male vs. female ratios were almost equal for all the groups: 47.9% and 47.9% for residents, 50.0% and 47.2% for tourists, and 52.9% and 47.1% for high school students. The proportion of respondents over 60 years of age was 61.6% for the residents and 71.2% for the tourists (), which was higher than the mean percentage of Sakuragawa citizens (Sakuragawa Statistical Abstract Citation2020). In terms of occupation, the proportion of ‘other’ was the highest among residents and visitors, suggesting that many of these respondents were retired. A majority of tourists and high school students lived outside of Sakuragawa city. Regarding outdoor recreation, 45.2% of the residents and 74.2% of the tourists answered that they do outdoor recreation frequently or sometimes. However, only 23.0% of high school students answered as such, with the rest selecting ‘interested but difficult to do’ or ‘not interested’. The proportion of student respondents who selected these two categories was significantly higher than those of the other groups (χ2 = 96.8, df = 6, p < 0.001).

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents

3.2. People’s attitudes toward wild cherries

The proportion of respondents who have a custom of viewing cherry blossoms was significantly higher among residents (80.0%) and tourists (95.6%) compared to high school students (50.0%) (χ2 = 115.3, df = 4, p < 0.001; ). When shown two images of two different types of scenic sites, both types were selected almost equally by residents, whereas wild cherries in natural forest was mainly selected by tourists (). For high school students, however, about 40% selected the planted trees, about 20% selected ones in natural forest, and the others chose ‘unknown or no difference’. The proportion of selected answers differed significantly among the three groups (χ2 = 80.3, df = 4, p < 0.001), indicating that students have different perceptions about the type of cherry trees. The proportion of respondents who preferred wild cherries to C. × yedoensis was higher among residents (48.6% vs. 22.2%) and tourists (52.2% vs. 17.4%; ), whereas high school students showed no preference, with 50.6% of respondents answering ‘I don’t know’ or ‘no difference between them’ (χ2 = 24.8, df = 4, p < 0.001). To the question about interest in conservation activities, the largest number of respondents selected participation in forest management, followed by environmental education (). This tendency was consistent over all the three groups. In response to the question about Satoyama, 69.4% of the residents and 76.1% of the tourists were able to explain Satoyama, whereas only 18.1% of high school students could do so, which was significantly lower than the other two groups (χ2 = 68.3, df = 2, p < 0.001; ).

Figure 3. Results of the questionnaire survey about respondents’ perceptions and experiences regarding wild cherries. (a) Q2-1 How often do you go cherry blossom viewing? (b) Q2-2 What image do you have of wild cherries? (c) Q2-3 Which do you like better, Cerasus × yedoensis or wild cherries? (d) Q2-4 What kind of activities are you interested in regarding the conservation of wild cherries? (Respondents were allowed to choose multiple answers.) (e) Q2-5 Do you have an image of Satoyama?.

3.3. Spatial distribution of perceived values

The respondents allocated the values to a relatively wide range of ecosystems services (). In the responses from residents and tourists, the value of aesthetic in spring (when the flowers bloom) was rated significantly higher than the other seven values (χ2 = 31.9, df = 7, p < 0.001 for residents; χ2 = 42.9, df = 7, p < 0.001 for tourists). High school students also valued aesthetic in spring as highest, but there was no statistical difference from the other values (χ2 = 3.7, df = 7, p > 0.8).

Figure 4. Averaged allocation (%) to eight types of ecosystem services according to the three groups of respondents.

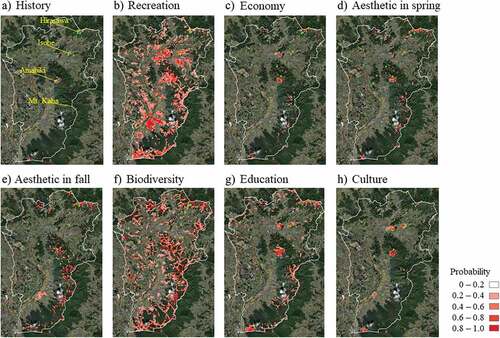

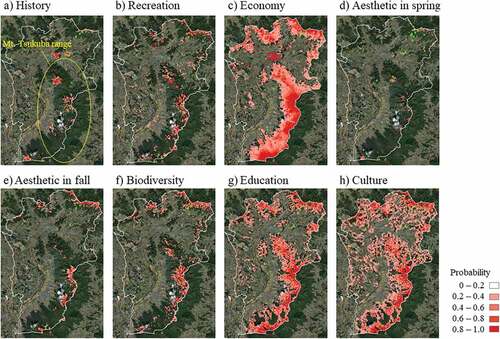

R ratios from the average neighbor statistical analyses were less than 1.0 for nearly all the values across the three groups (Appendix 2), indicating that the point data of each value were significantly concentrated in specific areas. The distribution of values derived from wild cherries was mapped using Maxent analyses (). In the responses from residents (), historical and aesthetic values in spring were estimated to be present at Hirasawa, Isobe, Amabiki, and Mt. Kaba, which are known as beautiful landscapes with flowering wild cherry trees. In this modeling, distance to tourism resources showed a strong contribution to the estimation of history (). Furthermore, aesthetic value in spring was higher at points with steeper slopes and plant communities typically seen in Satoyama ecosystems (i.e. Quercetum acutissimo-serratae Miyawaki 1967 and Castaneo-Quercetum serratae Okutomi, Tsuiji et Kodaira 1976) (Appendix 3a, b). Values of recreation and biodiversity were estimated to be distributed in larger areas than the other values; the areas with high probability were around the Tsukuba Mountain Range and low-elevation urban areas (). Again, slope and vegetation type made strong contributions when modeling these values, although distance to road showed a strong contribution to biodiversity as well (, Appendix 3c).

Figure 5. Distribution of values of ecosystem services derived from wild cherries according to residents. Grid cells with a distribution probability of 0.2 or higher are colored. The four areas in A) are famous scenic areas.

Figure 6. Distribution of values of ecosystem services derived from wild cherries according to tourists. Grid cells with a distribution probability of 0.2 or higher are colored.

Figure 7. Distribution of values of ecosystem services derived from wild cherries according to high school students. Grid cells with a distribution probability of 0.2 or higher are colored.

Table 2. Estimates of relative contributions of environmental variables to the Maxent model. See for the corresponding maps. DTF: Distance to Forest, DTT: Distance to Tourism resources, DTR: Distance to Road, DTW: Distance to Water, ELEV: Elevation, SLOPE: Slope, LAND: Land use type, VG: Vegetation

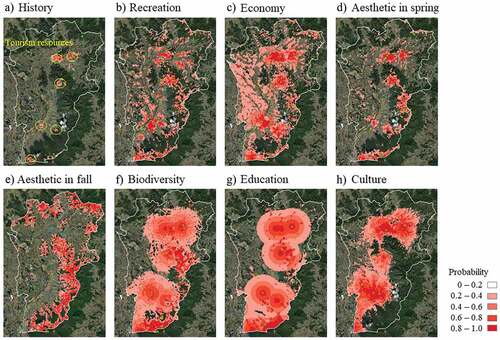

Tourists’ perceptions were more widely distributed in the Tsukuba Mountain Range (). This can typically be seen in the values of economy, education, and culture, for which elevation, land-use type, and slope, respectively, demonstrated the strongest contributions (). Yet, the distributions of values of history and aesthetic in spring were concentrated at specific scenic sites, as seen for the residents (). The variables making a strong contribution were distance to tourism resources for history, and slope and vegetation type for aesthetic in spring ().

The value perceptions of high school students were estimated to occur more closely to tourism resources (, ). This trend was conspicuous for values of history, biodiversity, and education. In addition, the southeastern part of Sakuragawa city near Mt. Tsukuba showed a relatively high probability of occurrence of perceived social values for ecosystem services.

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge, attitudes, and local value perceptions of ecosystem services provided by wild cherries

In this study, we focused on three types of socio-cultural groups and compared their knowledge, attitudes, and value perceptions of ecosystem services provided by symbolic wild cherries. As a result, there were considerable differences among the groups. First, local residents and tourists were more favorable to wild cherries than the common cultivar, and a majority of them had basic knowledge of wild cherries and Satoyama (). In contrast, many of the high school students surveyed did not seem to recognize the difference between wild cherries and the cultivar and could not describe the characteristics of Satoyama. These results imply that high school students have limited knowledge of and experiences with wild cherries. The value perceptions also varied markedly among the three groups. The residents and tourists rated aesthetic in spring as the highest value of wild cherries (), whereas high school students rated the eight values more equally. The results suggest that most of the students were not able to discriminate among the values due to limited knowledge of wild cherries. A majority of students commute from outside of the city () and expressed little interest in outdoor recreation. Thus, they likely had fewer opportunities to learn about and visit wild cherry sites in Sakuragawa city compared to residents and tourists. Differences in the perceived value of ecosystem services in local communities have been reported in other areas. In a study of a peri-urban forest in Djoumouna, Republic of Congo, there was marked variation among age groups in the recognition of sociocultural services, such as income, recreation, ecotourism, and source of inspiration (Kimpouni et al. Citation2021). According to a study of grassland ecosystems in Europe (Lamarque et al. Citation2011), perceptions of ecosystem services varied depending on a stakeholder’s knowledge of biodiversity and experiences in nature. In Slovenia, students’ frequency of direct experiences in forests had a positive correlation with the value they assigned to some ecosystem services of forests, especially cultural services (Torkar Citation2016). Our results agree with these findings. In other words, the students’ perceptions may change in the future through information outreach, education, and experiences with cherry trees in nature.

In a previous study, people living closer to the forest tended to appreciate more indirect services, such as regulating, cultural, and supporting services, than direct ones (Muhamad et al. Citation2014). In addition, tourists often focus more strongly on aesthetic values than the others (Zoderer et al. Citation2019). In this study, however, there was little difference in the importance of values between the residents and tourists () because the landscape of wild cherries, as well as its history and culture, are well recognized by local residents and those visiting from distant places. Perhaps different stakeholders tend to perceive the value of characteristic symbolic species like wild cherries in similar ways to the degree they have sufficient information on that species.

When local people are highly dependent on goods and income from the natural environment, their perceptions of ecosystem services tend to be focused on provisioning services (Camacho-Valdez et al. Citation2020; Kimpouni et al. Citation2021). In the present study, we did not observe such a pattern, suggesting that local people do not currently depend on timber and other goods from forests dominated by wild cherries. This reflects the fact that the social relationship between humans and Satoyama has greatly changed from the past, when people continuously utilized forests for their daily use.

4.2. Spatial distributions of value perceptions

Looking at the spatial distribution of perceived values, according to residents and tourists the values of aesthetic in spring and history were concentrated in narrow areas, which are famous for their beautiful scenery of wild cherries (). This result corresponds well with the fact that local residents emphasized aesthetic value in spring (). Yet for tourists, a large forested area around the Tsukuba Mountain Range was identified as having a high probability of the other values (). This contrast may be related to tourists’ preference for wild cherries in natural forests over the planted ones in Isobe (), such that they perceive more value in mountain forested areas rather than low-elevation urbanized areas. In a study conducted in Berlin, Germany, perceptions of cultural ecosystem services in urban green spaces were relatively concentrated in the inner city, where there is a higher population density and a large number of people can utilize the spaces (Rall et al. Citation2017). Our study, however, showed different patterns; both developed and rural/forested areas were perceived as having high values. This indicates that core-valued sites were well recognized by local residents as well as tourists, despite the sites being relatively scattered across Sakuragawa city.

The distribution of perceived values of high school students showed a markedly different pattern from those of the other two groups (, ). Perhaps the areas ranked as having high values, which correspond to areas where tourism resources exist, are frequently visited by the students, because these sites are also close to their schools in urbanized areas. The survey revealed that high school students are less familiar with wild cherries as compared to residents and tourists (). In addition, some of the students may not have been familiar with the geography of Sakuragawa city, such that they could not point out the wild cherry sites correctly (). Relatively weak interest in and knowledge of wild cherries may be linked to students’ spatially different perception of the values of wild cherries. In contrast, local residents and frequently visiting tourists are more likely familiar with wild cherry sites. In order to maintain the traditional values of local communities, it is important to encourage communication between young and elderly generations, which can help with filling the knowledge gap and sharing a variety of values provided by wild cherries. Such interactions are known to strengthen integrative understanding of ecosystem services (Bullock et al. Citation2018) and enrich human and social capital (Camacho-Valdez et al. Citation2020), thereby contributing to sustainable communities (Stålhammar Citation2021).

Among the environmental factors used in the analysis, distance to road, distance to tourism resources, slope, and vegetation type made large contributions in the models (). Social factors such as distance to road and distances to tourist resources had a significant influence on values that directly benefit human activities, such as history, economy, education, and culture. On the other hand, biophysical factors such as slope and vegetation type had an effect on values with indirect benefits, including aesthetic in spring, aesthetic in fall, and biodiversity. The probability of a site being perceived as having aesthetic value in spring was higher at points with steeper slopes (Appendix 3a). The result agrees with the ecological characteristics of wild cherries, as regeneration is more likely to occur on slopes with a high frequency of disturbance. For vegetation type, the probability tends to increase with the occurrence of vegetation types that are representative of Satoyama landscapes (Appendix 3b). The congruence between habitat characteristics of symbolic species and people’s value perceptions is quite important from the perspective of decision-making in community-based management because local stakeholders likely support habitat conservation of the species where it actually occurs. In addition, the distribution of the values generally increased as distance to road decreased (Appendix 3c), in agreement with other studies reporting that people are more likely to perceive ecosystem services when they are closer to a road (Riper et al. Citation2012, Citation2017; Sherrouse et al. Citation2014). In short, value perceptions of symbolic species are affected both by biophysical factors (i.e. habitat characteristics of the species) and accessibility issues (distance to road), and their spatial patterns can be integrated into conservation planning.

4.3. Limitations and future research perspectives

Although we found marked differences of value perceptions among the three groups, our study does have some limitations. First, the number of visitors to the festival was smaller than in previous years due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Sakuragawa city government, personal communication). Thus, respondents’ attributes might be different from those visiting in regular years. For example, the visitors surveyed may have come from closer areas than usual. At this point, we are unable to determine whether this potential bias affected the results or not, so our results should be interpreted with caution. Second, we focused on three socio-cultural groups, but other stakeholders such as foresters, farmers, conservation organizations, and commercial sectors may have different value perceptions of wild cherries. Inclusion of their views in additional studies would be necessary to implement comprehensive policy-making. Third, differences in age, sex, and educational levels were not examined here since it was outside the aims of our study. Relationships between these basic factors and value perceptions can be analyzed with a large-scale survey, which is also encouraged in the future.

4.4. Management implications

Our results indicated that there was a considerable difference among the stakeholders in value perceptions of ecosystem services provided by wild cherries, a symbol of the traditional forest landscape in Satoyama. For the conservation of such landscapes, it is important to share the diverse values, which are appreciated by local residents and knowledgeable visitors, with younger generations. Encouraging participation in community forest management and educational activities may improve communication among these stakeholders because all three groups expressed strong interest in these activities (). Above all, forest management by local communities could play a significant role; intensive management with short-rotation harvesting, as historically performed in Satoyama, is effective for the regeneration of wild cherries (Katsuda et al. Citation2020). Such activities likely strengthen the function of wild cherries as a symbol of sustainable resource use and biodiversity conservation.

In the Maxent model, the aesthetic value in spring, which was the most important to a majority of respondents, was distributed at well-known scenic sites (). These sites have great potential to encourage the setting aside of new protected areas and community-based management. In the decision-making process, land managers and city governments may propose new projects on such sites. On the other hand, wild cherries grow in many areas in the forests of the Tsukuba Mountain Range that were not marked by the respondents (Katsuda et al. Citation2020). Such places with high biological value and ecosystem services but not recognized by people are known as ‘warm spots’ (Alessa et al. Citation2008). These currently unrecognized valuable sites should also be the focus of future management and may be good choices for initiating new activities.

Although residents and tourists focused on aesthetic values in spring, many of them also selected other values. The historical value of cherries was also well appreciated about this unique cultural forest landscape. Plieninger et al. (Citation2015) argued that too much emphasis on only a few ecosystem services that are easily recognized may hinder the acquisition of multiple benefits related to other ecosystem services. Cultural ecosystem services are strongly related to quality of life and well-being, making them important in establishing sustainable communities (Bullock et al. Citation2018; Camacho-Valdez et al. Citation2020). Therefore, we encourage policy-makers and managers to consider symbolic wild cherries as an entry point to thinking about multidimensional values of cultural forest landscapes (i.e. Satoyama). It may be worthwhile to hold small workshops or meetings where various stakeholders can exchange their opinions about the values of wild cherries, which could broaden each person’s value perceptions while avoiding potential conflicts. A participatory mapping approach like the one we used in this study is useful in such discussions and promotes community-initiated (rather than governmental top-down) decision-making regarding the management of traditional wild cherry landscapes.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we found that local value perceptions of ecosystem services provided by wild cherries were diverse, but local residents and tourists both greatly appreciated aesthetic values in spring. This perception was developed based on their knowledge of wild cherries and Satoyama as well as their experiences in nature. Value perceptions were affected by several environmental factors, but the size of the effects differed among the groups. The areas they marked as important can be considered hotspots of locally perceived values and should be prioritized for designation as protected areas and places for community-based forest management. In addition, filling the knowledge gap about wild cherries in the younger generation is encouraged and can be implemented through workshops, advertisements, and education.

The traditional Satoyama landscape has high biodiversity and multiple cultural values, including aesthetic, recreational, and historical values. In general, however, the maintenance of Satoyama landscapes is challenging because it requires a large labor force and cooperation from land owners and local communities. Anthropogenic impacts, including development and land-use changes, are also serious threats to Satoyama. Nevertheless, the presence of symbolic tree species like wild cherries would help draw people’s attention and encourage their consistent support of conservation work. Moreover, it is relatively easy to evaluate the success of conservation projects when wild cherries, with conspicuous flowers that can be easily identified by the public, are used as a landscape indicator. Our research provides an example of the potential application of symbolic indicators for conservation and community-involved management of traditional forest landscapes. Wild cherry blossoms represent ecological and cultural associations between humans and nature in Japan. Their conservation as symbolic trees has implications for sustainable development and the provision of a variety of ecosystem services in the future.

Supplementary Materials

Download PDF (565.2 KB)Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Sakuragawa City Government, residents in the Isobe and Hirasawa districts, and all the respondents who kindly answered the questionnaire. We also appreciate the support of Dr. Nobu Kuroda, Dr. Yoshihiko Tsumura, Dr. Kiyokazu Kawada, and Dr. Masae Ishihara. Two anonymous reviewers provided valuable critiques and useful suggestions for revisions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2022.2065359

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abram NK, Meijaard E, Ancrenaz M, Runting RK, Wells JA, Gaveau D, Pellier A-S, Mengersen K. 2014. Spatially explicit perceptions of ecosystem services and land cover change in forested regions of Borneo. Ecosys Services. 7:116–127. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.11.004.

- Alessa LN, Kliskey AA, Brown G. 2008. Social-ecological hotspots mapping: a spatial approach. for identifying coupled social-ecological space. Landscape Urban Plan. 85(1):27–39. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.09.007.

- Bennett JR, Maloney R, Possingham HP 2015. Biodiversity gains from efficient use of private sponsorship for flagship species conservation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282, 20142693.

- Bennett EM, Peterson GD, Gordon LJ. 2009. Understanding relationships among multiple ecosystem services. Ecol Let. 12:1394–1404. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01387.x.

- Bowen-Jones E, Entwistle A. 2002. Identifying appropriate flagship species: the importance of culture and. local contexts. Oryx. 36:189–195. doi:10.1017/S0030605302000261.

- Bullock C, Joyce D, Collier M. 2018. An exploration of the relationships between cultural ecosystem services, socio-cultural values and well-being. Ecosys Services. 31:142–152. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.02.020.

- Camacho-Valdez V, Saenz-Arroyo A, Ghermandi A, Navarrete-Gutiérrez DA, Rodiles-Hernández R. 2020. Spatial analysis, local people’s perception and economic valuation of wetland ecosystem services in the Usumacinta floodplain, Southern Mexico. PeerJ. 8:e8395. doi:10.7717/peerj.8395.

- Chan KMA, Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould R, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain S, et al., 2016. Opinion: why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113, 1462–1465.

- Cheng X, Van Damme S, Li L, Uyttenhove P. 2019. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: a review of methods. Ecosys Services. 37:100925. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100925.

- Department of Conservation, New Zealand. 2021. New Zealand ferns. [Accessed 2021 May 16] https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-plants/ferns/

- Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute. 2010. Handbook of transformation to broadleaf forests. [Accessed 2021 May 16] (in Japanese) https://www.ffpri.affrc.go.jp/pubs/chukiseika/documents/2nd-chuukiseika22.pdf

- Fujii Y, Shiga S, Asahiro K, Shigematsu T. 2009. Growing and flowering situation of Prunus jamasakura for 9 years in urban forest reserve. Japanese Inst Landscape Arch. 72(5):523–526. (in Japanese with English summary). doi:10.5632/jila.72.523.

- García-Llorente MJ, Castro A, Quintas-Soriano C, Oteros-Rozas E, Iniesta-Arandia I, González JA, García Del Amo D, Hernández-Arroyo M, Casado-Arzuaga I, Palomo I, et al. 2020. Local perceptions of ecosystem services across multiple ecosystem types in Spain. Land. 9:330. doi:10.3390/land9090330.

- García-Nieto AP, Quintas-Soriano C, García-Llorente M, Palomo I, Montes C, Martín-López B. 2015. Collaborative mapping of ecosystem services: the role of stakeholders׳ profiles. Ecosys Services. 13:141–152. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.11.006.

- Garibaldi A, Turner N. 2004. Cultural keystone species: implications for ecological conservation and restoration. Ecol Soc. 9(3):1. [Accessed 2021 May 16]. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss3/art1/

- Grabherr G. 2009. Biodiversity in the high ranges of the Alps: ethnobotanical and climate change perspectives. Global Environ Change. 19:167–172. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.01.007.

- Graça M, Queirós C, Farinha-Marques P, Cunha M. 2018. Street trees as cultural elements in the city: understanding how perception affects ecosystem services management in Porto, Portugal. Urban Forestry Urban Greening. 30:194–205. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.02.001.

- Hattori T, Akamatsu H, Takeda Y, Kodate S, Kamihogi A, Yamazaki H. 1995. A study on the actual conditions of Satoyama (rural forests) and their management. Humans Nature. 6:1–32. (in Japanese with English summary).

- Home R, Keller C, Nagel P, Bauer N, Hunziker M. 2009. Selection criteria for flagship species by conservation organizations. Environ Conservation. 36(2):1–10. doi:10.1017/S0376892909990051.

- Ishii M, Nakagoshi N. 1997. Population structure of canopy trees and vegetation management of secondary forest in a forest-park planning. Japanese Inst Landscape Arch. 60(5):543–546. (in Japanese with English summary). doi:10.5632/jila.60.543.

- Japan Meteorological Agency. 2021. [Accessed 2021 May 16] (in Japanese) https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/view/annually_a.php?prec_no=40&block_no=0318&year=&month=&day=&view=

- Jepson P, Barua M. 2015. A theory of flagship species action. Conservation Soc. 13:95–104. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.161228.

- Katsuda K, Saeki I, Kamijo T. 2020. Regeneration patterns of Cerasus leveilleana (Koehne) H. Ohba and C. jamasakura (Siebold ex Koidz.) H. Ohba in Satoyama forests of Sakuragawa City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. J Jap Soc Revegetation Technology. 46(1):27–32. (in Japanese with English Summary).

- Katsuki T. 2015. Cherry blossoms. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten Publishers. (in Japanese).

- Kimpouni V, Nzila JDD, Watha-Ndoudy N, Madzella-Mbiemo MI, Yallo Mouhamed S, Kampe JP. 2021. Exploring local people’s perception of ecosystem services in Djoumouna Periurban Forest, Brazzaville, Congo. In:Źróbek-Sokolnik, A. Int J Forestry Res. 2021:6612649. doi:10.1155/2021/6612649.

- Konta F. 2016. Dendrology of cherry blossom. Tokyo: Gijutsuhyoronsha. (in Japanese).

- Lamarque P, Tappeiner U, Turner C, Steinbacher M, Bardgett RD, Szukics U, Schermer M, Lavorel S. 2011. Stakeholder perceptions of grassland ecosystem services in relation to knowledge on soil fertility and biodiversity. Regional Environ Change. 11:791–804. doi:10.1007/s10113-011-0214-0.

- Moriuchi E, Basil M. 2019. The sustainability of ohanami cherry blossom festivals as a cultural icon. Sustain MDPI Open Access J. 11(6):1–15. [Accessed 2021 May 16]. https://ideas.repec.org/a/gam/jsusta/v11y2019i6p1820-D217389.html

- Moutouama FT, Biaou SSH, Kyereh B, Asante WA, Natta AK. 2019. Factors shaping local people’s perception of ecosystem services in the Atacora Chain of Mountains, a biodiversity hotspot in northern Benin. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 15:38.

- Muhamad D, Okubo S, Harashina K, Parikesit P, Gunawan B, Takeuchi K. 2014. Living close to. forests enhances people’s perception of ecosystem services in a forest-agricultural landscape of West Java, Indonesia. Ecosys Services. 8:197–206. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.04.003.

- Nakamura K, Shigematsu T. 2000. A study on growing and flowering situation of Prunus jamasakura in urban forest reserve. Japanese Inst Landscape Arch. 63(5):469–472. doi:10.5632/jila.63.469.

- Ogura J. 2019. Decrease of grasslands from early to late periods of the Meiji era in Boso hills and Mt. Tsukuba area. Biol Sci. 70(4):217–224. (in Japanese).

- Orenstein DE, Groner E. 2014. In the eye of the stakeholder: changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border. Ecosys Services. 8:185–196. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.04.004.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Díaz S, Pataki G, Roth E, Stenseke M, Watson RT, Başak Dessane E, Islar M, Kelemen E, et al. 2017. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach. Current Opinion Environ Sustain. 26-27:7–16. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006.

- Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE. 2006. Maximum entropy modeling of species. geographic distributions. Ecol Modelling. 190:231–259.

- Plieninger T, Bieling C, Fagerholm N, Byg A, Hartel T, Hurley P, López-Santiago CA, Nagabhatla N, Oteros-Rozas E, Raymond CM, et al. 2015. The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Current Opinion Environ Sustain. 14:28–33.

- Primack RB. 2014. Essentials of conservation biology. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates.

- Primack RB, Higuchi H, Miller-Rushing AJ. 2009. The impact of climate change on cherry trees and other species in Japan. Biol Conservation. 142:1943–1949.

- Rall E, Bieling C, Zytynska S, Haase D. 2017. Exploring city-wide patterns of cultural ecosystem service perceptions and use. Ecol Indicators. 77:80–95.

- Riper CJ, Kyle GT, Sherrouse BC, Bagstad KJ. 2017. Toward an integrated understanding of perceived biodiversity values and environmental conditions in a national park. Ecol Indicators. 72:278–287.

- Riper CJ, Kyle GT, Sutton SG, Barnes M, Sherrouse BC. 2012. Mapping outdoor recreationists’ perceived social values for ecosystem services at Hinchinbrook Island National Park, Australia. Applied Geography. 35:164–173.

- Rüdisser J, Schirpke U, Tappeiner U. 2019. Symbolic entities in the European Alps: perception and use of a cultural ecosystem service. Ecosys Services. 39:100980.

- Sakuragawa City Government. 2019. Yamazakura Preservation and utilization plan in Sakuragawa City. [Accessed 2021 May 16] (in Japanese) https://www.city.sakuragawa.lg.jp/page/page006073.html

- Sakuragawa Statistical Abstract. 2020. [Accessed 2021 May 16] (in Japanese) https://www.city.sakuragawa.lg.jp/page/dir002288.html

- Sakurai R, Jacobson SK, Kobori H, Primack R, Oka K, Komatsu N, Machida R. 2011. Culture and climate change: Japanese cherry blossom festivals and stakeholders’ knowledge and attitudes about global climate change. Biol Conservation. 144:654–658.

- Sato T. 2005. “Japan” formed by cherry blossoms. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, Publishers.

- Scheyvens H, Mader A, Lopez-Casero F, Takahashi Y. 2019. Socio-Ecological production landscapes and seascapes as regional/local circulating and ecological spheres. Hayama: Institute for Global Environmental Strategies. [Accessed 2021 May 16] https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep21789.pdf

- Schirpke U, Meisch C, Tappeiner U. 2018. Symbolic species as a cultural ecosystem service in the European Alps: insights and open issues. Landscape Ecol. 33:711–730.

- Schröter M, van der Zanden EH, van Oudenhoven APE, Remme RP, Serna-Chavez HM, de Groot RS, Opdam P. 2014. Ecosystem services as a contested concept: a synthesis of critique and counter-arguments. Conservation Let. 7:514–523.

- Shackleton S, Chinyimba A, Hebinck P, Shackleton C, Kaoma H. 2015. Multiple benefits and values of trees in urban landscapes in two towns in northern South Africa. Landscape Urban Planning. 136:76–86.

- Sherrouse BC, Clement JM, Semmens DJ. 2011. A GIS application for assessing, mapping, and quantifying the social values of ecosystem services. Applied Geography. 31:748–760.

- Sherrouse BC, Semmens DJ 2015. Social Values for Ecosystem Services, Version 3.0 (SolVES 3.0): documentation and user manual. U.S. Geological Survey.

- Sherrouse BC, Semmens DJ, Ancona ZH. 2022. Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES): open-source spatial modeling of cultural services. Environ Model Software. 148:105259.

- Sherrouse BC, Semmens DJ, Clement JM. 2014. An application of Social Values for Ecosystem. Services (SolVES) to three national forests in Colorado and Wyoming. Ecol Indicators. 36:68–79.

- Shoyama K, Yamagata Y. 2016. Local perception of ecosystem service bundles in the Kushiro. watershed, northern Japan: application of a public participation GIS tool. Ecosys Services. 22:139–149.

- Sodhi NS, Lee TM, Sekercioglu CH, Webb EL, Prawiradilaga DM, Lohman DJ, Pierce NE, Diesmos AC, Rao M, Ehrlich PR. 2009. Local people value environmental services provided by forested parks. Biodiversity Conservation. 19:1175–1188.

- Stålhammar S. 2021. Assessing people’s values of nature: where is the link to sustainability transformations? Frontiers Ecol Evol. 9:624084. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.624084

- Takeuchi K. 2001. Nature conservation strategies for the ‘SATOYAMA’ and ‘SATOCHI’, habitats for secondary nature in Japan. Global Environ Res. 5(2):193–198.

- Torkar G. 2016. Secondary school students’ environmental concerns and attitudes toward forest ecosystem services: implications for biodiversity education. Int J Environ Sci Edu. 11(18):11019–11031.

- Washitani I. 2001. Traditional sustainable ecosystem ‘Satoyama’ and biodiversity crisis in Japan: conservation ecological perspective. Global Environ Res. 5(2):119–133.

- Yamamoto S, Takahashi R. 1991. Establishment of cherry-dotted coppice in the countryside. Japanese Institute Landscape Arch. 54(5):173–178. (in Japanese with English summary).

- Zoderer BM, Tasser E, Carver S, Tappeiner U. 2019. Stakeholder perspectives on ecosystem service supply and ecosystem service demand bundles. Ecosys Services. 37:100938.