ABSTRACT

Biocultural approaches are gaining attention for coping with current sustainability challenges. These approaches recognize that biological and cultural diversity are inextricably linked. Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) plays an important role in biocultural approaches as these often build on local cultural perspectives. This review explores how ILK is conceptualized and applied in the scientific literature published in Spanish on biocultural approaches to sustainability and examines the status and trends of ILK described in this literature. For this, we reviewed 72 publications and conducted a category-based qualitative content analysis. We found multiple conceptualizations of ILK, although most of them shared some commonalities, such as the close link to specific biocultural contexts. The results suggests that there are three themes that seem to be both relevant and controversial within the reviewed literature: the different strategies to bridging diverse knowledge systems, the conflictive views on the role of ILK in sustainability, and the threats to ILK. We also show that future research would benefit from greater attention to power relations and context-specific dynamics in bridging diverse knowledge systems, as there is still room to improve approaches and tools to promote the co-production of knowledge while supporting and enhancing the self-determination of IPLC. We conclude that the way biocultural approaches to sustainability engage with ILK can support shape a variety of alternative futures, which may differ from currently dominant perspectives on sustainability, and further demonstrate that the design and implementation of conservation policies that protect both people and nature can be enhanced.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

During the last decades, the increasing complexity of global sustainability challenges such as biodiversity loss and climate change has led to greater recognition of indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) in science and policy (Martello and Jasanoff Citation2004; Mistry and Berardi Citation2016; Brondízio et al. Citation2021). The interest in ILK emerged from the scientific disciplines of ethnobiology and human ecology, that focus on the comparative taxonomy of scientific and ethnoclassifications and nomenclature of species, as well as the study of ecological processes and human-nature relationships (Berkes Citation2018; López-Rivera Citation2020; McAlvay et al. Citation2021). By the late 1970s, ILK was considered from a very utilitarian perspective and emphasis was placed on the practical part of this knowledge (Bell Citation2009; Howes and Chambers Citation2009). For example, it was applied to improve agricultural production systems, which is why many scholars referred to this knowledge as indigenous technical knowledge (ITK) (Agrawal Citation1995; Bell Citation2009; Howes and Chambers Citation2009). In 1988, the First International Congress of Ethnobiology adopted the Declaration of Belém, which emphasized the importance of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) for the stewardship of biodiversity worldwide (see for definitions of IPLC and ILK). Ever since, greater recognition was given to the role of IPLC for legitimate and effective environmental governance (Brondizio and Tourneau Citation2016). For example, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted in 1992 and more recently the Global Assessment report by the IPBES, specifically stress the importance of ILK and IPLC for the conservation, promotion and sustainable use of biodiversity (United Nations Citation1992; IPBES Citation2019). For those initiatives to be successful, it has been proposed that abroad evidence based on diverse knowledge systems needs to be recognized and represented (Turnhout et al. Citation2012; Tengö et al. Citation2014, Citation2017; Brondizio and Tourneau Citation2016).

Box 1. Definitions of ILK and IPLC of the IPBES.

There are multiple scientific understandings and applications of ILK in research (Onyancha et al. Citation2018; Lam et al. Citation2020). For example, different terms have been proposed and are used to conceptualize the diverse bodies of knowledge hold by IPLC (Pierotti Citation2011), such as ‘local ecological knowledge’ (e.g. Davis and Wagner Citation2003), ‘indigenous knowledge’ (e.g. Gadgil et al. Citation1993), and ‘traditional ecological knowledge’ (e.g. Berkes Citation2018). ILK is also at the core of biocultural approaches since these approaches ‘explicitly start with and build on local cultural perspectives – encompassing values, knowledges, and needs – and recognise feedbacks between ecosystems and human well-being’ (Sterling et al. Citation2017, p. 3). Biocultural approaches build on the idea that, for as long as they have co-existed, people and nature have influenced each other and possibly co-evolved (Posey Citation1999; Maffi Citation2007; Rapport and Maffi Citation2010). This assumption is supported by the correlations found between regions rich in biological diversity and linguistic and cultural diversity (Loh and Harmon Citation2005; Gorenflo et al. Citation2012). Biocultural approaches can be also considered as a boundary concept that is interpreted in many ways, which is why the application of these approaches is wide-ranging (see the lenses or different ways of conceiving the biocultural identified by Hanspach et al. Citation2020). However, what they all have in common is the aim of understanding and interpreting human-nature relations (Merçon et al. Citation2019). As such, they offer an interdisciplinary perspective that allows for a complex, holistic understanding of socio-ecological systems (Sterling et al. Citation2017; Merçon et al. Citation2019). Despite the importance of ILK within biocultural approaches to sustainability, the meanings and applications of ILK have not received much attention in the corresponding scientific literature published in Spanish so far.

With this review, we provide new insights into how ILK is understood and applied in the scientific literature published in Spanish on biocultural approaches to sustainability by exploring conceptualizations, applications, as well as the status and current trends of ILK described in the reviewed literature. Although English has become the academic lingua franca, many scientists from non-Anglophone countries continue to publish research in languages other than English (Meneghini and Packer Citation2007, Gordin Citation2015, Vila Citation2021). This non-Anglophone science receives far less attention in scientific debates and policymaking, which can lead to biases in research and evidence-based decision making (Amano et al. Citation2016; Vila Citation2021). To date, language barriers still need to be addressed in science (Amano et al. Citation2021). For this reason, by publishing our findings in English, we would like to provide non-Spanish speakers access to highly relevant evidence that were previously not accessible to them, thereby helping to overcome language barriers.

2. Methods

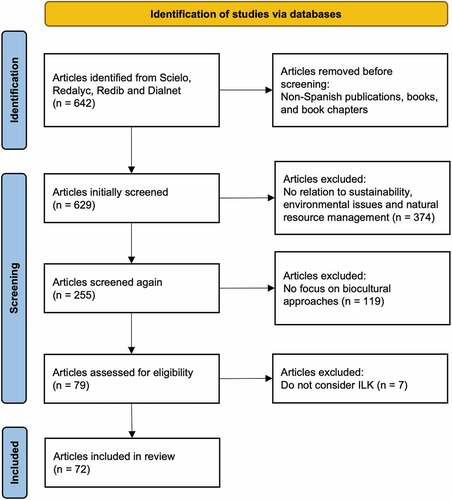

We conducted a systematic literature review (Luederitz et al. Citation2016), based on the review on biocultural approaches to sustainability in Spanish performed by Díaz‐Reviriego et al. (Citationunder review). The first compilation of the sample for this review consisted of searching the databases ‘Scielo’ (https://scielo.org), ‘Redib’ (www.redib.org), ‘Redalyc’ (www.redalyc.org) and ‘Dialnet’ (https://dialnet.unirioja.es) in December 2019. Since we were interested in the academic engagement with ILK in the Spanish-speaking community, we only considered Spanish language journal articles published from 1990 to 2018, recognizing that there is much more literature on this topic beyond that. To ensure that the article explicitly addresses biocultural approaches, we only included articles in which ‘biocultural’ was explicitly mentioned. Therefore, the Spanish keywords used for the search were ‘biocultural’ (singular) and ‘bioculturales’ (plural). This search recruited a total of 629 papers, excluding books and book chapters. We scrutinized the abstracts and selected those papers that related to sustainability and environmental issues, leaving 255 papers. Finally, only papers where biocultural approaches were the focus of the paper, i.e. biocultural was not only used as buzzword but was the main focus of the paper, where included in the review. Subsequently, all papers were reviewed, and the types of knowledges (scientific knowledge and ILK) considered was examined. The final sample for our analysis was constituted by the 72 papers that considered ILK in the study (see Appendix 1 for a complete list of all papers reviewed). summarizes the methodological approach in a flow diagram.

In order to explore the (a) conceptualizations, (b) applications, and (c) status and current trends of ILK described in the scientific literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability in Spanish, we conducted a category-based qualitative content analysis (Mayring and Fenzl Citation2019). For the sub-questions (a) and (b), we deductively developed eight categories and inductively developed codes within these categories. These are for sub-question (a): terms, aspects, characteristics, holders, and most knowledgeable people and for sub-question (b): functions, bridging strategies and challenges (see Appendix 2 for a table with a description of all codes and references). For sub-question (c), we adopted all categories for direct and underlying threats and conservation actions from the comprehensive meta-analysis carried out by Tang and Gavin (Tang and Gavin Citation2016). This includes six codes for direct threats, ten codes for underlying threats, and five codes for conservation actions (see Appendix 2 for a complete list of all codes, for a detailed description of these codes see Tang and Gavin Citation2016, p. 60–64). Additionally, whenever the paper included a place-based component, we coded the country to which the paper referred to. In the broadest sense, we included references to all types of knowledge held by IPLC. We were as broad and inclusive as possible to avoid presupposing a conceptualization of ILK ourselves, since exploring different conceptualizations of ILK is one of the goals of this study.

Coding was done with the software ‘MAXQDA’ (VERBI Software Citation2019). After a first round of coding all papers, we revised the category system and the coding guide. Subsequently, we read the papers again, checked all coded segments and, if necessary, corrected or supplemented them. During the second coding round, we did not modify the coding guide anymore. This ensured that we coded all papers applying the same category system. The coding procedure was conducted by one person (L.B.).

We analyzed the results quantitatively by determining the frequency of each category. Additionally, we reviewed all coded segments and produced a brief qualitative summary, containing the most important points for the most important subcategories. All direct quotations from the reviewed literature were translated from Spanish into English by the author.

3. Results

3.1. Geographical distribution

The majority of the papers reviewed (76%) had a place-based component in Latin America, half of which (47%) were case studies conducted in Mexico (see Appendix 3 for a map of the number of case studies per country). This shows that the publications are geographically very unevenly distributed. Many studies have been conducted in a few countries (e.g. Mexico, Chile), while other Latin American countries such as Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, or many Central American countries were not covered. There were only a few papers based outside of Latin America: two case studies in Spain (Calvet-Mir et al. Citation2014; Socies Fiol and Cuéllar Padilla Citation2017) and a paper that referred, besides local communities in Mexico and Costa Rica, to a traditional community in China (Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013). Five papers had no place-based component.

3.2. Conceptualizations of ILK

There was a variety of terms used to refer to the knowledge of IPLC and only seven papers referred to ILK without explicitly mentioning a specific term. In total, we found five terms used to conceptualize ILK: knowledge, heritage, memory, wisdoms, and world views. These concepts were intimately linked and, in most cases, used interchangeably.

Most papers (79%) used the term ‘knowledge’ when referring to ILK. These papers emphasized different characteristics of ILK by using a very broad range of adjectives. ‘Traditional’ (61%), ‘local’ (50%) and ‘ecological/environmental’ (31%) knowledge were most frequently mentioned. Furthermore, there were papers (47%) that used the term ‘heritage’ as a way to conceptualize ILK, which was defined as ‘that which reminds us of our ancestors’ by some authors (Vásquez Gonzalez, Citation2016, p. 205). In other papers (25%), ILK was referred to as ‘memory’. Many authors defined ‘biocultural memory’ drawing on Toledo and Barrera-Bassols (Citation2008). Accordingly, memory comprises at least three different dimensions: a genetic, linguistic, and cognitive dimension, which fulfil the function of the diversity of genes, languages, and knowledge (Toledo and Barrera-Bassols Citation2008; as cited in Costanzo Citation2016). Thus, ‘biocultural memory […] represents the capacity of a community to remember in order to understand the present and, consequently, gives elements for planning the future and tracing similar events that have occurred in the past’ (Toledo and Barrera-Bassols Citation2008; as cited in Nuñez-García et al. Citation2012, p. 201).

We identified four different aspects that were attributed to ILK: practices, local and empirical knowledge, world views and social institutions. Many papers referred in this context to the conceptualization of ILK proposed by Toledo et al. (Citation2001) where ILK is understood as a ‘kosmos-corpus-praxis’-complex. Most of the papers considered several aspects and 28 papers addressed all four categories. The aspect we identified most frequently is ‘practices’ (also referred to as ‘praxis’) (88%), including agricultural practices and natural resource management systems, as well as crafts, medical practices, and cooking activities (e.g. Nuñez-García et al. Citation2012). Many articles (82%) also mentioned ‘local and empirical knowledge’ (‘corpus’), relating to the possession of information. In some cases, only ecological knowledge such as knowledge about animals, plants or landscapes was considered (e.g. Campregher Citation2011; Socies Fiol and Cuéllar Padilla Citation2017). In other papers also specialized types of knowledge, such as medical or astronomical knowledge, was considered (e.g. Hilgert et al. Citation2014; Rozzi Citation2016; Hirose López Citation2018). Additionally, most papers took world views (‘kosmos’) into account (78%). These comprise belief systems that are manifested in special ceremonies and rituals as well as in customs and norms (e.g. taboos) in daily life (Tetreault and Lucio López Citation2011). The world views depicted in the reviewed literature are usually based on the ontological perspective where nature is considered to be sacred (Madrigal Calle et al. Citation2016). Finally, social institutions, although never explicitly mentioned as such, were considered by more than half of the papers (53%). In particular, social principles such as reciprocity or solidarity, which determine the organization of a community, were cited in this context (Argueta Villamar Citation2016).

We identified a wide range of different characteristics attributed to ILK. Most papers (58%) described ILK as being deeply rooted in its local context. These papers emphasized the strong, inseparable relationship between the local population and their environment. For this reason, ILK was usually regarded as sensitive to its specific environment and contextually bound (e.g. Garrido Peña Citation2014; Ramos Muñoz et al. Citation2018; Figueroa Burdiles and Vergara-Pinto Citation2018). Many authors described the ‘co-evolution’ of humans and nature (e.g. Campregher Citation2011; Luque et al. Citation2012a; Jiménez Ruiz et al. Citation2016), thus meaning that nature and culture have always been influencing each other in their evolution over a very long period of time. Furthermore, some papers referred to the concept of ‘territory’, i.e. a geographical area symbolically and instrumentally appropriated by a community (Lucio Citation2015). ILK was usually depicted as held by peasant or indigenous populations. Only few papers (6%) indicated that ILK can also be held by urban communities (Tetreault and Lucio López Citation2011; Luque et al. Citation2012a; Calvet-Mir et al. Citation2014, Ruiz Barajas Citation2018). Some described that indigenous people lived in urban environments even before colonization (Tetreault and Lucio López Citation2011). Others referred to outmigration towards urban areas and in some places, urban population is now even higher than rural population (Luque et al. Citation2012b). Furthermore, some papers mentioned individuals or groups who were considered to be most knowledgeable (17%). In some papers (7%) elderly people were considered as more knowledgeable about agrobiodiversity (Socies Fiol and Cuéllar Padilla Citation2017; Colin-Bahena et al. Citation2018), medicinal plants (Pérez Mesa Citation2013) and the cultural identity of their community (Espinoza López et al. Citation2016). Other papers also referred to gendered knowledge. For example, in some studies (7%), women were considered as being most knowledgeable by indicating that only or mainly they are responsible for certain activities, such as mushroom picking (Jiménez Ruiz et al. Citation2016), food rituals (Hernández Bernal Citation2016), traditional farming, including the selection of fruits for obtaining seeds (Socies Fiol and Cuéllar Padilla Citation2017), or the management of local agrobiodiversity (Arguello and Cueva Citation2009). In other cases, as in the study by Rodríguez-Ramírez et al. (Citation2017), they noted that usually only sons accompany their fathers to the forest, field, or milpa, so men tend to hold more knowledge about nature and birds than women in their case study. Finally, specialist knowledge was also described by Hirose López (Citation2018) in reference to the h’men (Mayan priest) being the most knowledgeable within his community since he gathers all the knowledge of Mayan healing arts, especially herbal medicine.

3.3. Applications of ILK

Most papers (92%) described how ILK can contribute to biocultural approaches to sustainability. Firstly, most papers (78%) emphasized that ILK contributes to biodiversity conservation, giving a variety of explanations. Some papers indicated that IPLC promote biodiversity diversification through the creation of agrobiodiversity, which for this reason is often only conserved in the gardens of IPLC (e.g. Luque et al. Citation2012b; Pérez and Matiz-Guerra Citation2017). Hence, their role is crucial for the in-situ conservation of many domesticated species (Calvet-Mir et al. Citation2014). Other papers went beyond and contended that ILK also contributes to the conservation of wild species and ecosystems through oral expressions of biocultural memory. For example, Contador et al. (Citation2018) referred to the narrative of the Yagan community in southern Chile about the Omora hummingbird. This narrative expresses a traditional knowledge that understands and values the importance of biodiversity for the long-term sustainability of freshwater ecosystems as a source of drinking water for humans and animals (Contador et al. Citation2018). For this reason, the holders of this knowledge may contribute to maintaining the integrity and continuity of the ecosystem, including all living and non-living elements. Furthermore, some papers depicted how IPLC conserve biodiversity by actively defending the environment against external, anthropogenic threats. Toledo (Citation2013) spoke of the ‘indigenous insurgency of Latin America’ (p. 57) which opposes international policies that promote global warming. Some papers also illustrated this with specific examples where IPLC took legal action against forestry and mining companies and blocked local infrastructures in order to prevent them from operating in their territories and causing the loss of local biodiversity (e.g. Tetreault and Lucio López Citation2011; Martínez González and Corgos López-Prado Citation2014). Despite positive examples of resistance that led to a shift in national policies towards the protection of biodiversity, there were also examples where the resistance of IPLC was suppressed and therefore could not support the conservation of the local biodiversity (e.g. Martínez Coria and Haro Encinas Citation2015).

Secondly, more than half of the reviewed papers (53%) argued that ILK contributes to a transformation towards sustainability. However, the ideas about such a transformation and the role of ILK in it vary widely or are even contradictory. On the one hand, there were authors arguing that ILK can effectively contribute to sustainable development since IPLC have developed forms of life and practices that are closely linked to nature and respect the environment (e.g. Socies Fiol and Cuéllar Padilla Citation2017; Hernández Hernández et al. Citation2018). Some papers emphasized that ILK complements scientific knowledge as it may help to overcome the dichotomy between nature and culture that is inherent to scientific knowledge systems (Jasso Arriaga Citation2018). On the other hand, there were authors describing a transformation towards sustainability without referring to the concept of sustainable development. In these papers, ILK was regarded as an opportunity for transformational pathways that differ from or even contradict sustainable development (e.g. Toledo Citation2013; Bravo Osorio Citation2016; Guzmán Citation2016). Notions of development that are based on the application of ILK were referred to using different terms, including ‘endogenous development’ (Arguello and Cueva Citation2009), ‘ethnic development’ (Gonzales Citation2017) and ‘local community development’ (Bello Cervantes and Pérez Serrano Citation2017). Furthermore, some authors also strongly criticized the concept of development in general. They argued that it creates a dichotomous hierarchy of underdevelopment and development, which implies that, in order to achieve a desirable life, people must go through the development that ‘developed’ people have already gone through (García Campos Citation2013). Martínez Coria and Haro Encinas (Citation2015) pointed out that the concept of development has failed to combat poverty and inequalities in the past and is therefore unable to meet the current sustainability challenges. For other authors, the concept of development, i.e. the idea of a linear process of life that establishes an earlier or later state, does not exist within ILK (García Campos Citation2013). For this reason, ILK is expected to potentially be the base for the initiation of a paradigm shift that enables ‘overcoming the discussions that focus on the depletion of resources […] with a view to development and supposed progress, which only leaves us a loss of diversity at different levels’ (Bravo Osorio Citation2016, p. 164). Nonetheless, counter-hegemonic pathways to development were rarely specified. The Andean concept of ‘Buen Vivir’ was explicitly mentioned by a few authors (e.g. García Campos Citation2013; Toledo Citation2013; Martínez Coria and Haro Encinas Citation2015). ‘Buen Vivir’ refers to the idea of ‘be[ing] in harmony with oneself, with human beings, with the world of nature and with the transcendent’ (Toledo Citation2013, p. 58) and was perceived as an alternative to the prevailing Eurocentric modernist paradigm (Costanzo Citation2016).

In many papers ILK and scientific knowledge were seen as complementary to each other (e.g. Martínez Coria and Haro Encinas Citation2015; Torrescano Valle et al. Citation2018). These authors contended that despite this, ILK is often not considered in science and policy and its holders are marginalized in these contexts. For this reason, these authors stressed the necessity of bridging ILK and scientific knowledge (e.g. Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013; Pérez Mesa Citation2014; Mancera-Valencia et al. Citation2018) and described how to facilitate and shape this process, and various bridging strategies were described. The strategy most frequently mentioned was the development and implementation of co-management systems that involve IPLC and scientists equally (38%). The need of developing strategies that facilitate full rapprochement between and participation of public institutions and IPLC was highlighted (Tetreault and Lucio López Citation2011). Various papers referred to the Mexican management approach of Biosphere Reserves, which actively involves IPLC into the development and implementation of an integral and sustainable management concept of their territories (e.g. Tetreault and Lucio López Citation2011; Romero Ugalde Citation2016; Rodríguez-Ramírez et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, some authors pointed out that participatory research, i.e. ‘doing research with people rather than about people’ (Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013, p. 5), is crucial for bridging scientific knowledge and ILK (29%). The idea of participatory research involving IPLC was described by many different terms such as ‘biocultural research’ (Nemogá, Citation2016), the ‘transdisciplinary approach’ (Crego et al. Citation2018), ‘ethnoecological/ethnobiological investigation’ (e.g. Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013; de Los La Torre Cuadros Citation2013) or ‘participatory action research’ (Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013). These papers highlighted that research should adopt a ‘biocultural focus’ and look for alliances and agreements with IPLC (Nemogá, Citation2016). This will help to overcome the prevailing authority and predominance of scientific knowledge and contribute to nature conservation management systems where ILK is accounted for and not subordinated (Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013). Moreover, it was stressed that IPLC should be actively involved into the research process from the very beginning, including the definitions of objectives (Bello Cervantes and Pérez Serrano Citation2017). This was seen as a precondition to ensure that the results not only reflect the interests of the researchers, but also the priorities and needs of IPLC and promote the benefits for the communities involved (Cordero Romero & Palacio, Citation2018).

Several papers (43%) described challenges that hinder or prevent bridging ILK and scientific knowledge. Most frequently mentioned were power asymmetries between IPLC and scientists, which limit the ability of IPLC to actively participate in decision-making processes (31%). Costanzo (Citation2016) spoke of a ‘dual conception in which there are ‘two worlds’, one supposedly ‘backward’, where the rural population and indigenous people […] are found and another where knowledge and modernity reside, which without being discussed or debated, solve any problem in their own perfect way’ (p. 48). This so-called ‘abysmal thinking’ divides the scientific knowledge from other knowledge systems and favors power asymmetries (García Campos Citation2013). Bravo Osorio (Citation2016) stressed that these power asymmetries are an expression of an ongoing colonial process that subordinates other epistemologies and reinforces paradigms of control and cultural homogenization. Consequently, IPLC suffer from marginalization in the access to economic and institutional resources compared to scientists, which leads to an additional disadvantage (Luque Agraz and Doode Matsumoto Citation2009). As a consequence of these multiple power asymmetries, the dialogue between IPLC and scientists might be hindered or even prevented.

3.4. Status and current trends of ILK

Most papers (92%) referred to direct and underlying threats, that lead to a continuous erosion and loss of ILK. For these drivers of ILK degradation, we adopted the classification of Tang and Gavin (Citation2016). We found all six direct threats proposed by them also in the reviewed literature. Almost half of the papers reviewed (49%) mentioned the change of environment and natural resources as a direct driver of ILK degradation. As ILK is deeply rooted in local contexts, its continued existence directly depends on the conservation of the natural environment. Consequently, the degradation of the environment entails the degradation of ILK (Calvet-Mir et al. Citation2014). In this context, extreme weather events related to climate change such as droughts (Luque et al. Citation2012b) and wildfires (Figueroa Burdiles and Vergara-Pinto Citation2018) as well as biodiversity loss, water, air and soil pollution, deforestation, desertification, habitat destruction and fragmentation, urbanization and the overexploitation of natural resources were mentioned (e.g. Luque et al. Citation2012b; Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013; Espinoza López et al. Citation2016). Of the ten underlying threats proposed by Tang and Gavin (Citation2016) we found nine in the literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability. Only the threat of war and military occupation proposed by them was not considered in the reviewed literature. Most frequently mentioned were government policy and legislation that discriminate against IPLC and therefore contribute to the degradation of ILK (47%). Many papers see state policies as usually based on the premise of promoting neoliberal development and economic growth (e.g. Gonzales Citation2017; Cariño Olivera and Castillo Maldonado Citation2017; Medici Citation2018). Therefore, they do not consider the needs and interests of IPLC as these are often perceived as obstacles to development and growth (Guzmán Citation2016). Under the premise of a modernizing development, the heterogeneity of the local population is made invisible in order to impede the processes that could challenge the current model (Guzmán Citation2016). Other threats different than those included in Tang and Gavin (Citation2016) were not identified within the reviewed literature.

The threats we identified occur on different spatial and temporal scales. Whereas some papers referred to threats at a local level, as for example the migration of IPLC from rural to urban areas (e.g. Moreno-Calles et al. Citation2013; Calvet-Mir et al. Citation2014), other papers considered globalization as a threat (e.g. Campregher Citation2011; Hirose López Citation2018). Moreover, there were papers that describe unique events such as the relocation of indigenous peoples from their ancestral territory (e.g. Pérez Mesa Citation2013; Martínez Coria and Haro Encinas Citation2015), and papers that referred to processes that take place over a longer period of time, such as the persistent marginalization of IPLC (e.g. Pérez Mesa Citation2014; Espinoza López et al. Citation2016).

We found several papers that suggested ways to address the direct and underlying threats to ILK degradation in order to maintain and foster these knowledge systems (71%). We identified all six categories for these conservation actions proposed by Tang and Gavin (Citation2016). Most frequently mentioned were community-based conservation activities, i.e. the in-situ conservation of ILK that is based on ideas proposed by IPLC (38%). These include environmental conservation activities (e.g. Calvet-Mir et al. Citation2014; Hirose López Citation2018) as well as ILK commoditization (e.g. Espinoza López et al. Citation2016; Bello Cervantes and Pérez Serrano Citation2017). The latter refers to the transformation of aspects of ILK into goods to which previously no monetary value was attributed. This includes, for example, the implementation of biocultural tourism activities, based on the active participation of IPLC (e.g. Rodríguez-Ramírez et al. Citation2017; Jasso Arriaga Citation2018). These activities may provide IPLC a sustainable livelihood option and thus revitalize and promote their traditional way of living. Moreover, education and awareness building are mentioned as actions for the conservation of ILK (21%). These include formal educational activities such as the inclusion of ILK in school curricula, as well as informal activities including workshops and the promotion of festivals, competitions, and television programs aimed at reviving traditional cultures (e.g. Aldasoro Maya and Argueta Villamar Citation2013; Hernández Hernández et al. Citation2018).

4. Discussion

We explored how ILK is conceptualized and used in the scientific literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability in Spanish. Overall, there are multiple conceptualizations of ILK within the biocultural approaches reviewed, although they shared some commonalities that include various aspects that are seen as the foundational of these knowledge systems: they are (1) linked to specific biocultural contexts, (2) experiential and practice-based, which shapes the intracultural diversity of knowledge, as gendered knowledge and specialist knowledge, and (3) maintained through customary norms, institutions and world views. Our results also highlight that ILK is considered to be held, in most cases, by peasant or indigenous communities and only a few studies took place in urban areas. This tendency of biocultural approaches to be mostly undertaken in rural or indigenous context has been highlighted by Cocks et al. (Citation2006), Cocks and Wiersum (Citation2014) and Cocks and Shackleton (Citation2020). These authors show and commend the opportunities that biocultural approaches offer to studies in urban areas. Drawing on this, we put forward that diversifying the contexts in which ILK is considered within biocultural approaches could be a fruitful future research pathway. Also, our results show that geographically, most place-based research was conducted in Latin America and especially in Mexico. This might be due to the influence of the seminal work of Mexican researchers Victor M. Toledo and Narciso Barrera-Bassols on biocultural memory (Toledo and Barrera-Bassols Citation2008) and Eckart Boege on biocultural heritage (Boege Citation2008), which were very frequently cited within the literature reviewed.

For the way in which ILK is applied in biocultural approaches, we have identified three key themes that seem to be both relevant and controversial within the reviewed literature: (1) the different strategies to bridging diverse knowledge systems, (2) the conflictive views on the role of ILK in sustainability, and (3) the threats to ILK. We devote the rest of this section to discussing these key themes.

4.1. Bridging knowledge systems: complementing or co-producing knowledge?

First, we will discuss the different knowledge bridging strategies we found. Our review reveals that within biocultural approaches to sustainability, there are diverse ways to bridging ILK and scientific knowledge, such as cross-fertilization and co-production. While the idea of cross-fertilization focuses on convergences of diverse knowledge systems, co-production of knowledge seeks to co-produce new understandings of a defined problem by acknowledging convergences as well as possible divergences between ILK and scientific knowledge (Tengö et al. Citation2014; Roue and Nakashima Citation2018).

Papers referring to the idea of cross-fertilization of knowledge emphasize the complementarity of ILK and scientific knowledge systems and stress the importance of a mutual learning process that benefits all of those involved in the process (e.g. Bello Cervantes and Pérez Serrano Citation2017). For example, Figueroa Burdiles and Vergara-Pinto (Citation2018) point out that local knowledge, ‘when appropriately and symmetrically positioned with technical and scientific knowledge’ (p. 119), can contribute to the prevention and regeneration of territories affected by natural wildfires because of the memory that has historically been built around these disasters. Thus, ILK complements scientific knowledge in terms of its temporal scope. Notwithstanding, considering ILK and scientific knowledge exclusively as complementary could lead to neglecting that knowledge systems can also be contradictory and incommensurable. For example, Torrents-Ticó et al. (Citation2021) conducted a case study in the Sibiloi National Park area in Kenya and found that, despite many convergences between ILK and scientific knowledge, there are also many differences in perceptions of occurrence and trends of threatened and conflict carnivores. While photo and track rates indicated low abundance for all species surveyed, a high percentage of respondents considered some species to be abundant (Torrents-Ticó et al. Citation2021). This example suggests that the idea of knowledge systems complementarity and integration should not be solely understood as ILK filling in the gaps of science, as this narrow understanding can gloss over irreconcilable knowledge systems and world views (Klenk and Meehan Citation2015; Klenk et al. Citation2017; Turnhout et al. Citation2020).

The idea of co-production of knowledge acknowledges the divergences between ILK and scientific knowledge. These approaches are defined as ‘a collaborative process of bringing a plurality of knowledge sources and types together to address a defined problem and build an integrated or systems-oriented understanding of that problem’ (Armitage et al. Citation2011, p. 996). Thus, the different knowledge systems are not considered as two separate entities that mutually enrich each other, but, in a reciprocal process of knowledge generation, new knowledge is created (Tengö et al. Citation2014). This idea is also adopted by some authors of the reviewed literature. An illustrative case of this approach within the literature review is the work by Avellaneda-Torres et al. (Citation2014). They propose a framework for building community management plans through a process of rapprochement and participatory dialogue between IPLC and environmental authorities to developing new co-management systems in a mutual learning process. Positive examples, such as the Ashaninka Community Reserve in Peru, show that co-management systems may enable local actors to actively reduce existing power asymmetries (Caruso Citation2011). Nevertheless, some critical scholars have highlighted that co-management may also have unintended effects by fostering unequal power relations that disadvantage IPLC and hampering the pathway to indigenous self-determination (Natcher Citation2001; Nadasdy Citation2005; Armitage et al. Citation2011). Indigenous scholars argue that co-management may be an obstacle to indigenous self-determination as it reinforces ‘the reduction of complex legal-political orders, anchored in specific lands, value systems, rights, and practices, to material culture’. Accordingly, co-management is regarded as a ‘state-ratified international rights regime’ (Grey and Kuokkanen Citation2020, p. 919), which is why it necessarily undermines indigenous self-determination and endangers the cultural heritage of IPLC. They further argue that ‘the solution is not to improve co-management but to remove it as a barrier to Indigenous peoples’ governance over their own cultural heritage’ (p. 920) since cultural heritage can only be preserved in situ. Other indigenous scholars emphasize that indigenous self-determination does not mean representing and interpreting indigenous voices, but rather giving indigenous people a space to express their perspectives themselves (Adese et al. Citation2017).

Taken together, our results show that, despite the diversity of bridging strategies we found in the literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability, the interweaving of different knowledge systems remains a challenge. First, since the focus is often only on the complementarity of ILK and scientific knowledge, this approach could potentially neglect differences between knowledge systems. Second, because even when differences are acknowledged, many bridging strategies can in practice perpetuate unequal power relations that disadvantage IPLC and hinder indigenous self-determination. This shows that attention to power relations and context-specific dynamics is required for bridging diverse knowledge systems and that there is still a room for improving approaches and tools to promoting the co-production of knowledge that simultaneously support and enhance indigenous self-determination.

4.2. ILK for sustainable development or ILK as an alternative pathway?

The second, controversially discussed key theme we found in the reviewed literature is about the role of ILK in sustainable development. While some papers argue that ILK can contribute to sustainable development (e.g. Rodríguez-Ramírez et al. Citation2017; Socies Fiol and Cuéllar Padilla Citation2017; Hernández Hernández et al. Citation2018), others consider ILK as a possibility to create new transformational pathways that are detached from the idea of sustainable development (e.g. García Campos Citation2013; Bravo Osorio Citation2016; Guzmán Citation2016). The following paragraph is devoted to discussing the role of ILK and biocultural approaches in transformative pathways to more sustainable futures.

In the wider political discourse, the idea that ILK goes hand in hand with sustainable development is supported by influential development agencies such as the World Bank (World Bank Citation1998). In 1998, they developed a framework for ‘applying indigenous knowledge in development processes’ (World Bank Citation1998). Likewise, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) emphasizes that ‘indigenous knowledge, cultures and traditional practices contribute to sustainable and equitable development’ (United Nations Citation2007, p. 2). Among the papers reviewed some are illustrative of the idea that ILK can contribute to sustainable development. For example, Socies Fiol and Cuéllar Padilla (Citation2017) describe that ILK associated with the management of traditional varieties is key to the development of strategies that ensure the conservation of these varieties as well as to ensure the food security of the local population, and thus to the design of sustainable and resilient development processes. Others also support this idea, although highlighting that despite ILK and IPLC are receiving increasing attention in development policy, IPLC still do not have sufficient access to effective participation in current sustainable development initiatives such as the Agenda 2030 (Buenavista et al. Citation2018; Yap and Watene Citation2019). According to these authors, IPLC can make important contributions to the discourse on sustainable development and suggest that biocultural approaches can support to bring IPLC voices so that they are active agents of sustainable development, rather than passive recipients.

In contrast, other authors consider that ILK can be the knowledge base to build an alternative to sustainable development and problematize the concept of sustainable development in general (e.g. García Campos Citation2013; Bravo Osorio Citation2016). These authors argue that sustainable development emerged from a purely scientific perspective. Accordingly, sustainable development encompasses economic growth and follows a linear process of life that establishes an earlier and later state, which often does not exist in ILK (García Campos Citation2013). These arguments are also made beyond the literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability. Kothari et al. (Citation2014) argue that ILK should not be forced into this concept but be perceived as an opportunity to shape entirely new transformational pathways that are completely detached from the idea of sustainable development. Other scholars also point out that, so far, economic growth has failed to deliver on the promise of sustainable development since it does not recognize the biophysical limits of the planet (Caradonna Citation2018; de Souza Silva Citation2018; Otero et al. Citation2020). Post-development views see development and growth as part of the problem of unsustainability rather than the solution (Harcourt Citation2014; Kothari et al. Citation2019; Chassagne Citation2019). Our results show that some of the biocultural approaches to sustainability also adopt this post-development perspective. In the search for alternatives to the development paradigm, some authors refer to the concept of ‘Buen Vivir’ (e.g. García Campos Citation2013; Toledo Citation2013; Costanzo Citation2016). However, this is also a contested concept in academic debates and is interpreted in very different ways, such as a way of living or as a ‘post’ utopia (Gudynas Citation2011; Gudynas and Acosta Citation2011; Cuestas Caza Citation2019).

The results of our review indicate that there is no consensus on the role that ILK and biocultural approaches play for transformational pathways to more sustainable futures, but rather a plurality of perspectives about how ILK might support and shape alternative futures. Nevertheless, there is an increasing awareness that ILK and IPLC are key to better understanding and shaping context-specific and grounded transformational pathways, as they provide a valuable local perspective to the complex and uncertain global sustainability challenges.

4.3. Threats to ILK

Biocultural approaches build on the idea that humans and nature are inextricably linked and start from local cultural perspectives (Maffi Citation2007; Sterling et al. Citation2017). In this review, we examined the trends of ILK presented in the scientific literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability by looking at what direct and indirect threats are described that lead to a degradation of ILK. We recognize that ILK is a dynamic body of knowledge that is constantly adapting to changing environmental and social conditions (Gómez-Baggethun and Reyes-García Citation2013). Nonetheless, there is a pervasive loss and erosion of ILK systems (Fernández-Llamazares et al. Citation2021), which is why in the next section we will examine and discuss how biocultural approaches to sustainability address this issue.

Our findings reveal that there is an integrative understanding of the biological and cultural degradation, which was most frequently expressed through joint direct threats driving the erosion of ILK and of the environment. This link between environmental and sociocultural degradation is often not considered in the wider scientific discourse, which does not necessarily adopt a biocultural perspective. The meta-analysis conducted by Tang and Gavin (Citation2016) included English- and Chinese-language academic literature as well as literature from government agencies and nongovernmental organizations on ILK. Their results show that only approximately 20% of the cases considered mention changes in the environment and natural resources as a direct threat to ILK, whereas in our review of biocultural approaches almost half of the papers address this threat.

In the reviewed literature, war and military occupation were not explicitly mentioned as a threat to ILK. This is surprising given that Latin America remains, despite democratic developments, one of the most violent regions in the world (Kurtenbach Citation2019). More than two-thirds of the murders of land and environmental defenders in 2020 occurred in Latin American countries, with indigenous environmentalists particularly at risk of violence (Scheidel et al. Citation2020; Global Witness Citation2021). More recent literature already explores the role of armed conflicts in biocultural approaches in relation to nature’s rights, whereby nature is recognized as a victim of armed conflicts in Colombia (Ramírez Hernández and Leguizamon Arias Citation2020) through a biocultural rights approach for recognizing nature.

Overall, the integrative understanding of a biocultural degradation that we found in the reviewed literature indicates that, for ILK to thrive and flourish and to respect and support IPLC diverse ways of living, actions that simultaneously address socio-cultural and environmental threats to ILK are needed. Accordingly, the establishment of databases for the protection and spread of ILK, which has become increasingly popular since the 1990s (Agrawal Citation2002), while contributing to the ex-situ preservation of diverse knowledge systems, is not sufficient to adequately support the lived, embodied and contextualized nature of every knowledge system, including ILK. Rather, ILK may be maintained through continuous development, testing, and updating of knowledge (Gómez-Baggethun and Reyes-García Citation2013). This implies that IPLC are recognized as having sovereignty over their land, ecological means of production, technology, and livelihood-related knowledge systems (Gómez-Baggethun and Reyes-García Citation2013). The ILK conservation actions that we identified in this analysis would better be attuned to promote the revitalization and continuing of ILK when they explicitly support IPLC rights, recognize their contributions to understand and address social-environmental issues and acknowledge the dynamic and adaptive nature of ILK (Reyes-García et al. Citation2021; Brondízio et al. Citation2021). Also, since the threats driving ILK degradation occur at different spatial and temporal scales, the implementation of a single conservation measure such as co-management systems will most likely not be able to address the many dimensions of ILK threats. Rather, a variety of concerted multi-scalar and temporal conservation actions would be required.

The findings of our analysis indicate that the biocultural paradigm might foster the development and implementation of conservation actions that combine environmental and cultural conservation activities in a single holistic and integrative conservation management concept (Merçon et al. Citation2019). The increasing importance of biocultural approaches may further promote the effective participation of IPLC in conservation policy in a framework where ILK is not subordinated to scientific knowledge. This may require a paradigm shift in conservation policy from protecting the nature from people to protecting the nature with its people. It also implies that not only sustainability goals such as ‘ensuring the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems’ (UN General Assembly Citation2015, p. 29) are met, but also indigenous normative goals, since IPLC are increasingly actively involved in the development and implementation of co-management systems, which enables them to articulate and defend their interests (Burgos-Ayala et al. Citation2020).

With this review, we showed that ILK plays an important role in the academic literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability in Spanish. Our findings suggest that the consideration of ILK in biocultural approaches to sustainability can help shape a variety of alternative futures that may differ from currently dominant perspectives on sustainability. Moreover, the development and implementation of conservation actions that protect both people and nature can be enhanced through engagement with ILK in biocultural approaches. Future research should pay more attention to power relations and context-specific dynamics in bridging different knowledge systems and that there is still a need to improve approaches to knowledge co-production that simultaneously support and strengthen indigenous self-determination.

Supplementary Materials

Download PDF (866.7 KB)Acknowledgments

This research draws on a review of biocultural approaches to sustainability in the scientific literature published in Spanish and we gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Camila Benavides Frias, María García-Martín, Berta Martín-López, Stefan Ortiz Przychodzka, Elisa Oteros-Rozas, and Mario Torralba for their contributions to that.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2022.2157490

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adese J, Todd Z, Stevenson S. 2017. Mediating Métis identity: an interview with Jennifer Adese and Zoe Todd. MediaTropes. 7(1):26.

- Agrawal A. 1995. Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Dev Change. 26(3):413–15. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1995.tb00560.x.

- Agrawal A. 2002. Indigenous knowledge and the politics of classification. Int Soc Sci J. 54(173):287–297. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00382.

- Aldasoro Maya EM, Argueta Villamar A. 2013. Colecciones Etnoentomológicas Comunitarias: Una Propuesta Conceptual y Metodológica. Etnobiología. 11(2):1–15.

- Amano T, González-Varo JP, Sutherland WJ. 2016. Languages are still a major barrier to global science. PLoS Biol. 14(12):e2000933. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2000933.

- Amano T, Rios Rojas C, Boum Y II, Calvo M, Misra BB. 2021. Ten tips for overcoming language barriers in science. Nat Hum Behav. 5(9):1119–1122. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01137-1.

- Arguello M, Cueva K. 2009. La revalorización de la agroecología andina: estrategia local de diálogo de saberes para enfrentar problemas globales. Letras Verdes, Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Socioambientales. 5:12–14. doi:10.17141/letrasverdes.5.2009.850.

- Argueta Villamar A. 2016. El estudio etnobioecológico de los tianguis y mercados en México. Etnobiología. 14(2):38–46.

- Armitage D, Berkes F, Dale A, Kocho-Schellenberg E, Patton E. 2011. Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Glob Environ Change. 21(3):995–1004. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.04.006.

- Avellaneda-Torres LM, Torres Rojas E, León Sicard TE. 2014. Agricultura y vida en el páramo: una mirada desde la vereda El Bosque (Parque Nacional Natural de Los Nevados). Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural. 11(73):105–128. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.CDR11-73.avpm.

- Bell M. 2009. The exploitation of indigenous knowledge or the indigenous exploitation of knowledge: whose use of what for what? IDS Bull. 10(2):44–50. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.1979.mp10002008.x.

- Bello Cervantes IPS, Pérez Serrano AMM. 2017. Turismo biocultural: relación entre el parimonio biocultural y el fenómeno turístico. Experiencias investigativas. Scripta Ethnologica. XXXIX:109–128.

- Berkes F. 2018. Sacred ecology. Philadelphia and London, UK: Taylor and Francis.

- Boege E. 2008. El patrimonio biocultural de los pueblos indígenas de México: hacia la conservación in situ de la biodiversidad y agrodiversidad en los territorios indígenas. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropoligía e Historia.

- Bravo Osorio LM. 2016. Escuela, memoria biocultural y territorio: el caso de la práctica pedagógica integral en la institución educativa Inga Yachaikury (Caquetá-Colombia). Educación y ciudad. 30:159–166. doi:10.36737/01230425.v.n30.2016.1596.

- Brondízio ES, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y, Bates P, Carino J, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Ferrari MF, Galvin K, Reyes-García V, McElwee P, Molnar Z, et al. 2021. Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: indigenous and local knowledge, values, and practices for nature. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 46(1):481–509. annurev-environ-012220-012127. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-012127.

- Brondizio ES, Tourneau FML. 2016. Environmental governance for all. Science. 352(6291):1272–1273. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5122.

- Buenavista DP, Wynne-Jones S, McDonald M. 2018. Asian indigeneity, indigenous knowledge systems, and challenges of the 2030 agenda. East Asian Community Rev. 1(3–4):221–240. doi:10.1057/s42215-018-00010-0.

- Burgos-Ayala A, Jiménez-Aceituno A, Torres-Torres AM, Rozas-Vásquez D, Lam DPM. 2020. Indigenous and local knowledge in environmental management for human-nature connectedness: a leverage points perspective. Ecosyst People. 16(1):290–303. doi:10.1080/26395916.2020.1817152.

- Calvet-Mir L, Garnatje T, Parada M, Vallés J, Reyes-García V. 2014. Más allá de la producción de alimentos: los huertos familiares como reservorios de diversidad biocultural. Ambienta. 107:40–53.

- Campregher C. 2011. Conservación de la diversidad bio-cultural en Costa Rica: comunidades indígenas y el ambiente. Cuadernos de antropología. 21(1):1–20.

- Caradonna JL, editor. 2018. Routledge handbook of the history of sustainability. London ; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Cariño Olivera MM, Castillo Maldonado AL. 2017. Oasis Sudcalifornianos: Paisajes bioculturales con elevada capacidad adaptativa a la aridez y potencial para la construcción de la sustentabilidad local. Fronteiras. 6(2):217–239. doi:10.21664/2238-8869.2017v6i2.p217-239.

- Caruso E. 2011. Co-management redux: anti-politics and transformation in the Ashaninka Communal Reserve, Peru. Int J Herit Stud. 17(6):608–628. doi:10.1080/13527258.2011.618254.

- Chassagne N. 2019. Sustaining the ‘Good Life’: Buen Vivir as an alternative to sustainable development. Community Dev J. 54(3):482–500. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsx062.

- Cocks ML, Bangay L, Wiersum KF, Dold AP. 2006. Seeing the wood for the trees: the role of woody resources for the construction of gender specific household cultural artefacts in non-traditional communities in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Environ Dev Sustain. 8(4):519–533. doi:10.1007/s10668-006-9053-4.

- Cocks M, Shackleton C. 2020. Situating biocultural relations in city and townscapes: conclusion and recommendations. In: Cocks M Shackleton C, editors. Urban nature: enriching belonging, wellbeing and bioculture. London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; p. 241–268.

- Cocks ML, Wiersum F. 2014. Reappraising the concept of biocultural diversity: a perspective from South Africa. Hum Ecol. 42(5):727–737. doi:10.1007/s10745-014-9681-5.

- Colin-Bahena H, Monroy R, Velázquez-Carreño H, Velázquez-Carreño A, Monroy-Ortiz C. 2018. El tianguis de Coatetelco, Morelos: articulador de la conservación biocultural en el territorio. Revista Etnobiología. 16(2):87–97.

- Contador T, Rozzi R, Kennedy J, Massardo F, Ojeda J, Caballero P, Medina Y, Molina R, Saldivia F, Berchez F, et al. 2018. Sumergidos Con Lupa en los Ríos del Cabo de Hornos: Valoración Ética de los Ecosistemas Dulceacuícolas y Sus Habitantes. Magallania (Chile). 46(1):183–206. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442018000100183.

- Cordero Romero SS, Palacio G. 2018. Parques Nacionales desde la percepción local: A propósito del Parque Nacional Natural Amacayacu (Amazonas, Colombia). Mundo Amazónico. 9(2):199–227. doi:10.15446/ma.v9n2.65747.

- Costanzo M. 2016. Perspectivas de cambio desde el Sur. Pensamiento crítico desde la raíz. Cuadernos de Filosofía Latinoamericana. 37(115):45–69. doi:10.15332/25005375/2488.

- Crego R, Ward N, Jiménez JE, Massardo F, Rozzi R 2018. Los ojos del árbol: Percibiendo, registrando, comprendiendo y contrarrestando las invasiones biológicas en tiempos de rápida homogeneizacion biocultural. Magallania (Chile). 46(1):137–153. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442018000100137.

- Cuestas Caza J. 2019. Sumak Kawsay. ÁNFORA. 26(47):109–140. doi:10.30854/anf.v26.n47.2019.636.

- Davis A, Wagner JR. 2003. Who knows? On the importance of identifying “experts” when researching local ecological knowledge. Hum Ecol. 31(3):463–489. doi:10.1023/A:1025075923297.

- de Los La Torre Cuadros MA. 2013. Nota científica: hacia un enfoque biocultural en los programas de conservación de la naturaleza. Etnobiología. 11(1):53–57.

- de Souza Silva J. 2018. Investigación Científica ¿Para el desarrollo o para la vida? Mauritius: Editorial Adadémica Española.

- Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A, Adhikari JR, Arico S, Báldi A, et al. 2015. The IPBES conceptual framework — Connecting nature and people. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 14:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002.

- Díaz-Reviriego I, Hanspach J, Benavides Frias C, Burke L, García-Martín M, Ortiz Przychodzka S, Oteros-Rozas E, Torralba M. underreview. A review of biocultural approaches to sustainability in the Spanish literature.

- Espinoza López PC, Bañuelos Flores N, López Reyes M. 2016. Entre capullos de mariposas y fiestas. Hacia una alternativa de turismo indígena en El Júpare, Sonora, México. Estudios Sociales. 47:313–344.

- Fernández-Llamazares Á, Lepofsky D, Lertzman K, Armstrong CG, Brondizio ES, Gavin MC, Lyver PO, Nicholas GP, Pascua P, Reo NJ, et al. 2021. Scientists’ warning to humanity on threats to indigenous and local knowledge systems. J Ethnobiol. 41(2): doi:10.2993/0278-0771-41.2.144.

- Figueroa Burdiles N, Vergara-Pinto F. 2018. Reserva Nacional China Muerta: Consideraciones en torno a la conservación biocultural de la naturaleza, los incendios forestales y la herida colonial en territorios indígenas. Cultura-Hombre-Sociedad. 28(1):102–127. doi:10.7770/cuhso-v28n1-art1324.

- Gadgil M, Berkes F, Folke C. 1993. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio. 22(2/3):151–156.

- García Campos H. 2013. La educación ambiental con enfoque intercultural. Atisbos latinoamericanos. Revista Bio-grafía. 6(11):161–168. doi:10.17227/20271034.11biografia161.168.

- Garrido Peña F. 2014. Topofilia, paisaje y sostenibilidad del territorio. Enrahonar. 53:63–75. doi:10.5565/rev/enrahonar.174.

- Global Witness. 2021. LAST LINE OF DEFENCE: the industries causing the climate crisis and attacks against land and environmental defenders.

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Reyes-García V. 2013. Reinterpreting change in traditional ecological knowledge. Hum Ecol. 41(4):643–647. doi:10.1007/s10745-013-9577-9.

- Gonzales T. 2017. Turismo, cocinas, sabores y saberes locales y regionales sostenibles en Perú. Turismo y Patrimonio. 11(11):37–51. doi:10.24265/turpatrim.2017.n11.04.

- Gordin MD. 2015. Scientific Babel: how science was done before and after global English. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Gorenflo LJ, Romaine S, Mittermeier RA, Walker-Painemilla K. 2012. Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 109(21):8032–8037. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117511109.

- Grey S, Kuokkanen R. 2020. Indigenous governance of cultural heritage: searching for alternatives to co-management. Int J Herit Stud. 26(10):919–941. doi:10.1080/13527258.2019.1703202.

- Gudynas E. 2011. Buen vivir: Germinando alternativas al desarrollo. América Latina en Movimiento. 462:1–20.

- Gudynas E, Acosta A. 2011. El buen vivir mas alla del desarrollo. Revista Quehacer. 181: 70–83

- Guzmán D. 2016. Diversidad biocultural y género: Trayectorias productivas de mujeres campesinas de Chiloé. Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales. 31(31):25–42. doi:10.4206/rev.austral.cienc.soc.2016.n31-02.

- Hanspach J, Haider J, Oteros-Rozas E, Olafsson A, Gulsrud N, Raymond M, Torralba M, Martín-López B, Bieling C, Garcia-Martin M, et al. 2020. Biocultural approaches to sustainability: a systematic review of the scientific literature. People Nat. 2(3):1–17. doi:10.1002/pan3.10120.

- Harcourt W. 2014. The future of capitalism: a consideration of alternatives. Cambridge J Econ. 38(6):1307–1328. doi:10.1093/cje/bet048.

- Hernández Bernal MC. 2016. Los alimentos en la vida ritual de los nahuas de San Juan Tetelcingo, Guerrero. Un elemento a considerar dentro del patrimonio biocultural. Dimensión Antropológica. 23(66):64–86.

- Hernández Hernández BR, Santiago Ibañez DP, Miguel Velasco AE, Cruz Carrasco C, Regino Maldonado J. 2018. Empresas sociales rurales, estrategía de desarrollo sustentable y conservación del patrimonio cultural inmaterial. Caso: “Amaranto (Amaranthus spp) de Mesoamerica. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios. 42:955–967.

- Hilgert N, Lambare AD, Vignale ND, Stampella PC, Pochettino ML. 2014. ¿Especies naturalizadas o antropizadas? Apropiación local y la construcción de saberes sobre los frutales introducidos en época histórica en el norte de Argentina. Revista Biodiversidad Neotropical. 4(2):69–87. doi:10.18636/bioneotropical.v4i2.118.

- Hill R, Adem Ç, Alangui WV, Molnár Z, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y, Bridgewater P, Tengö M, Thaman R, Adou Yao CY, Berkes F, et al. 2020. Working with Indigenous, local and scientific knowledge in assessments of nature and nature’s linkages with people. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 43:8–20. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.006.

- Hirose López J. 2018. La medicina tradicional maya: ¿Un saber en extinción? Revista Trace. 74(74):114–134. doi:10.22134/trace.74.2018.174.

- Howes M, Chambers R. 2009. Indigenous technical knowledge: analysis, implications and issues. IDS Bull. 10(2):5–11. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.1979.mp10002002.x.

- IPBES. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn: IPBES secretariat.

- IPBES. 2021. Glossary. https://ipbes.net/glossary/indigenous-peoples-local-communities.

- Jasso Arriaga X. 2018. Análisis y perspectivas para gestionar el turismo biocultural: una opción para conservar el ecosistema forestal de Temascaltepec. Madera y Bosques. 24(1):1–14. doi:10.21829/myb.2018.2411451.

- Jiménez Ruiz AE, Thomé-Ortiz H, Burrola-Aguilar C. 2016. Patrimonio biocultural, turismo micológico y etnoconocimiento. El Periplo Sustentable. 30:180–205.

- Klenk N, Fiume A, Meehan K, Gibbes C. 2017. Local knowledge in climate adaptation research: moving knowledge frameworks from extraction to co‐production. WIREs Climate Change. 8(5): doi:10.1002/wcc.475.

- Klenk N, Meehan K. 2015. Climate change and transdisciplinary science: problematizing the integration imperative. Environ Sci Policy. 54:160–167. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.05.017.

- Kothari A, Demaria F, Acosta A. 2014. Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: alternatives to sustainable development and the green economy. Development. 57(3–4):362–375. doi:10.1057/dev.2015.24.

- Kothari A, Salleh A, Escobar A, Demaria F, Acosta A. 2019. pluriverse. New Delhi: Tulika Books.

- Kurtenbach S. 2019. The limits of peace in Latin America. Peacebuilding. 7(3):283–296. doi:10.1080/21647259.2019.1618518.

- Lam DPM, Hinz E, Lang DJ, Tengö M, von Wehrden H, Martín-López B. 2020. Indigenous and local knowledge in sustainability transformations research: a literature review. Ecol Soc. 25(1):art3. doi:10.5751/ES-11305-250103.

- Loh J, Harmon D. 2005. A global index of biocultural diversity. Ecol Indic. 5(3):231–241. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2005.02.005.

- López-Rivera A 2020. Blurring global epistemic boundaries: the emergence of traditional knowledge in environmental governance. Global Cooperation Research Papers.

- Lucio C. 2015. Mezcales y diversidad biocultural en los alrededores del Volcán de Colima. El caso de los productores tradicionales de Zapotitlán de Vadillo. EntreDiversidades. 5(5):13–43. doi:10.31644/ED.5.2015.a01.

- Luederitz C, Meyer M, Abson DJ, Gralla F, Lang DJ, Rau AL, Von Wehrden H. 2016. Systematic student-driven literature reviews in sustainability science - an effective way to merge research and teaching. J Clean Prod. 119:229–235. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.005.

- Luque Agraz D, Doode Matsumoto S. 2009. Los comcáac (seri): hacia una diversidad biocultural del Golfo de California y estado de Sonora. Estudios sociales (Hermosillo, Son). 17:273–301.

- Luque D, Martinez-Yrizar A, Búrquez A, Gómez A, Nava E, Rivera M. 2012a. Pueblos indígenas de Sonora: el agua, ¿Es de todos? Region y Sociedad. 3:53–89.

- Luque D, Martinez-Yrizar A, Búrquez A, Gómez E, Nava A, Rivera M. 2012b. Política ambiental y territorios indígenas de Sonora. Estudios sociales. 2:257–280.

- Madrigal Calle BE, Escalona Maurice M, Vivar Miranda R. 2016. Del meta-paisaje en el paisaje sagrado y la conservación de los lugares naturales sagrados. Sociedad y Ambiente. 1(9):1–25. doi:10.31840/sya.v0i9.1631.

- Maffi L. 2007. Biocultural diversity and sustainability. In: Pretty JN, editor. The SAGE handbook of environment and society. Los Angeles: SAGE; p. 267–277.

- Mancera-Valencia FJ, Ávila Reyes AA, Amador Guzmán PM. 2018. Educación y patrimonio biocultural: construcción de una experiencia en la educación indígena de la sierra Tarahumara. IE Revista de investigación educativa de la REDIECH. 9(16):119–132. doi:10.33010/ie_rie_rediech.v9i16.116.

- Martello M, Jasanoff S. 2004. Introduction: globalization and environmental governance. In: Jasanoff S Martello M, editors. Earthly politics: local and global in environmental governance. Cambridge: MIT Press; p. 1–29.

- Martínez Coria R, Haro Encinas JA. 2015. Derechos territoriales y pueblos indígenas en México: Una lucha por la soberanía y la nación. Revista Pueblos y fronteras digital. 10(19):228. doi:10.22201/cimsur.18704115e.2015.19.52.

- Martínez González P, Corgos López-Prado A. 2014. La pesca artesanal en Jalisco. Conflictos en torno a la conservación biocultural y la reproducción del capital. El caso de Careyitos. Sociedad y Ambiente. 1(4):23–38. doi:10.31840/sya.v0i4.1522.

- Mayring P, Fenzl T. 2019. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In: Baur N Blasius J, editors. Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden; p. 633–648.

- McAlvay AC, Armstrong CG, Baker J, Elk LB, Bosco S, Hanazaki N, Joseph L, Martínez-Cruz TE, Nesbitt M, Palmer MA, et al. 2021. Ethnobiology phase VI: decolonizing institutions, projects, and scholarship. J Ethnobiol. 41(2): doi:10.2993/0278-0771-41.2.170.

- Medici A. 2018. Metabolismo social con la naturaleza, pluralismo jurídico y derechos emergentes. ABYA-YALA. 2(3):101–116. doi:10.26512/abyayala.v2i3.23248.

- Meneghini R, Packer AL. 2007. Is there science beyond English?: Initiatives to increase the quality and visibility of non‐english publications might help to break down language barriers in scientific communication. EMBO Reports. 8(2):112–116. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400906.

- Merçon J, Vetter S, Tengö M, Cocks M, Balvanera P, Rosell JA, Ayala-Orozco B. 2019. From local landscapes to international policy: contributions of the biocultural paradigm to global sustainability. Global Sustain. 2:e7. doi:10.1017/sus.2019.4.

- Mistry J, Berardi A. 2016. Bridging indigenous and scientific knowledge. Science. 352(6291):1274–1275. doi:10.1126/science.aaf1160.

- Moreno-Calles A, Toledo V, Casas A. 2013. Los sistemas agroforestales tradicionales de México: Una aproximación biocultural. Bot Sci. 91(4):375–398. doi:10.17129/botsci.419.

- Nadasdy P. 2005. The anti-politics of TEK: the institutionalization of co-management discourse and practice. Anthropologica. 47(2):215–232.

- Natcher DC. 2001. Co-Management: an aboriginal response to frontier development. North Rev. 23:146–163. Summer 2001.

- Nemogá G. 2016. Diversidad biocultural: Innovando en investigación para la conservación. Acta Biológica Colombiana. 21(1):311–319. doi:10.15446/abc.v21n1Supl.50920.

- Nuñez-García R, Fuente Carrasco M, Venegas-Barrera C. 2012. La avifauna en la memoria biocultural de la juventud indígena de la Sierra Juárez de Oaxaca, México. Universidad y Ciencia. 28(3):201–216.

- Onyancha O, Ngulube P, Maluleka J, Mokwatlo K. 2018. Towards a uniform terminology for indigenous knowledge concepts: informetrics perspectives. Afr J Libr Arch Inf Sci. 28:155–167.

- Otero I, Farrell KN, Pueyo S, Kallis G, Kehoe L, Haberl H, Plutzar C, Hobson P, García‐márquez J, Rodríguez‐labajos B, et al. 2020. Biodiversity policy beyond economic growth. Conser Lett. 13(4): doi:10.1111/conl.12713.

- Pérez D, Matiz-Guerra LC. 2017. Uso de las plantas por comunidades campesinas en la ruralidad de Bogotá D.C., Colombia. Caldasia. 39(1):68–78. doi:10.15446/caldasia.v39n1.59932.

- Pérez Mesa MR. 2013. Concepciones sobre biodiversidad desde la perspectiva de la diversidad cultural.dos estudios de caso. Revista Bio-grafía. 6(11):43–59. doi:10.17227/20271034.vol.6num.11bio-grafia43.59.

- Pérez Mesa MR. 2014. Miradas de la biodiversidad y la diversidad cultural: una reflexión a propósito de la enseñanza de las ciencias. Revista Tecné, Episteme y Didaxis: TED. 413–418.

- Pierotti RJ. 2011. Indigenous knowledge, ecology, and evolutionary biology. New York: Routledge.

- Posey DA. 1999. Introduction: culture and nature – the inextricable link. In: Page in United Nations Environment Programme, editors. Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity. London: Intermediate Technology Publications; pp. 1–18.

- Ramírez Hernández NE, Leguizamon Arias WY. 2020. La naturaleza como víctima en la era del posacuerdo colombiano. El Ágora USB. 20(1):260–274. doi:10.21500/16578031.4296.

- Ramos Muñoz DE, Álvarez Gordillo MG, Morales López MC. 2018. Sustentabilidad y Patrimonio Biocultural en la Reserva de la Biosfera del Ocote. Trace. 74(74):9–37. doi:10.22134/trace.74.2018.165.

- Rapport D, Maffi L. 2010. The dual erosion of biological and cultural diversity: implications for the health of ecocultural systems. In: Pilgrim S Pretty JN, editors. Nature and culture: rebuilding lost connections. London; Washington, D.C: Earthscan; p. 103–122.

- Reyes-García V, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y, Benyei P, Bussmann RW, Diamond SK, García-Del-Amo D, Guadilla-Sáez S, Hanazaki N, Kosoy N, et al. 2021. Recognizing indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ rights and agency in the post-2020 biodiversity agenda. Ambio. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01561-7.

- Rodríguez-Ramírez M, Maya EM, Zamora C, Orozco J. 2017. Conocimiento y percepción de la avifauna en niños de dos comunidades en la selva Lacandona, Chiapas, México: hacia una conservación biocultural. Nova Scientia. 9(19):660. doi:10.21640/ns.v9i19.1033.

- Romero Ugalde M. 2016. Caldos para el Xont’e. La territorialidad simbólica como reto legislativo en Guanajuato. Acta Universitaria. 26(2):109–118. doi:10.15174/au.2016.1453.

- Roue M, Nakashima D. 2018. Indigenous and local knowledge and science: from validation to knowledge coproduction. In: Callan H, editor. The international encyclopedia of anthropology. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons; 1–11. doi:10.1002/9781118924396.

- Rozzi R. 2016. Bioética global y ética biocultural. Cuadernos de Bioética. XXVII(3a):339–355.

- Ruiz Barajas CAR. 2018. Patrimonio, Paisaje y Resiliencia. Un encuentro En Lo Colectivo. MILLCAYAC - Revista Digital de Ciencias Sociales. 321–334.

- Scheidel A, Del Bene D, Liu J, Navas G, Mingorría S, Demaria F, Avila S, Roy B, Ertör I, Temper L, et al. 2020. Environmental conflicts and defenders: a global overview. Glob Environ Change. 63:102104. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102104.

- Socies Fiol A, Cuéllar Padilla M. 2017. ¿Quién mantiene la memoria biocultural y la agrobiodiversidad en la isla de Mallorca? Algunos aprendizajes desde las variedades locales de tomate. Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares. 72(2):477. doi:10.3989/rdtp.2017.02.008.

- Sterling EJ, Filardi C, Toomey A, Sigouin A, Betley E, Gazit N, Newell J, Albert S, Alvira D, Bergamini N, et al. 2017. Biocultural approaches to well-being and sustainability indicators across scales. Nat Ecol Evol. 1(12):1798–1806. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0349-6.

- Tang R, Gavin M. 2016. A classification of threats to traditional ecological knowledge and conservation responses. Conserv Soc. 14(1):57–70. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.182799.

- Tengö M, Brondizio ES, Elmqvist T, Malmer P, Spierenburg M. 2014. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: the multiple evidence base approach. AMBIO. 43(5):579–591. doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0501-3.

- Tengö M, Hill R, Malmer P, Raymond CM, Spierenburg M, Danielsen F, Elmqvist T, Folke C. 2017. Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—lessons learned for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 26–27:17–25. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.005.

- Tetreault DV, Lucio López CF. 2011. Jalisco: Introducción pueblos indígenas Desde 1992 con el esta- y regiones de alto blecimiento del Convenio. Estudios sobre Estado y Sociedad. XVIII(51):165–199.

- Toledo VM. 2013. El paradigma biocultural: crisis ecológica, modernidad y culturas tradicionales. Sociedad y Ambiente. 1(1):50–60. doi:10.31840/sya.v0i1.2.

- Toledo VM, Alarcón-Chaires P, Moguel P, Olivo M, Cabrera A, Leyequien E, Rodríguez-Aldabe A. 2001. El Atlas Etnoecológico de México y Centroamérica: Fundamentos, Métodos y Resultados. Etnoecológica. 6(8):7–41.

- Toledo VM, Barrera-Bassols N. 2008. La Memoria biocultural: la importancia ecológica de las sabidurías tradicionales. Barcelona: Icaria editorial.

- Torrents-Ticó M, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Burgas D, Cabeza M. 2021. Convergences and divergences between scientific and indigenous and local knowledge contribute to inform carnivore conservation. Ambio. 50(5):990–1002. doi:10.1007/s13280-020-01443-4.

- Torrescano Valle N, Pradp Cedeño Á, Mendoza Palma N, Trueba Macías S, Cedeño Meza R, Mendoza Espinar A. 2018. Percepción comunitaria de las áreas protegidas, a más de 30 años de su creación en Ecuador. Trace. 74(74):60–91. doi:10.22134/trace.74.2018.166.

- Turnhout E, Bloomfield B, Hulme M, Vogel J, Wynne B. 2012. Listen to the voices of experience. Nature. 488(7412):454–455. doi:10.1038/488454a.

- Turnhout E, Metze T, Wyborn C, Klenk N, Louder E. 2020. The politics of co-production: participation, power, and transformation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 42:15–21. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009.

- UN General Assembly. 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. A/RES/70/1. New York, N.Y: United Nations General Assembly.

- United Nations. 1992. Convention on biological diversity. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil & New York, NY United Nations.

- United Nations. 2007. United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples.

- Vásquez González AY, Chávez Mejía C, Herrera Tapia F, Meléndez FC. 2016. La fiesta xita: Patrimonio biocultural mazahua de San Pedro el Alto, México. Culturales. 4(1):199–228.

- VERBI Software. 2019. MAXQDA 2020. VERBI Software. Berlin, Germany.

- Vila FX. 2021. The hegemonic position of English in the academic field. Eur J Lang Policy. 13(1):47–73. doi:10.3828/ejlp.2021.5.

- World Bank. 1998. Indigenous knowledge for development: A framework for action. Knowledge and Learning Center. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/388381468741607213/text/multi-page.txt

- Yap MLM, Watene K. 2019. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and indigenous peoples: another missed opportunity? J Hum Dev Capab. 20(4):451–467. doi:10.1080/19452829.2019.1574725.