ABSTRACT

Human and ecological values influence all aspects of governance and management processes and in doing so, contribute to environmental decisions and outcomes. However, there is an absence of coherent and well-developed guidance to assist understanding of how values influence the different aspects of environmental governance and management. This paper addresses the gap between environmental values theory and governance and management practice. With in the context of Government policy making and implementation we examine the meaning and influence of principle, contextual and relational values in connection to the normative, empirical, and applied aspects of environmental governance and management. We present a conceptual framework articulating the relationships between value types and their influence on governance and management processes, demonstrating that management actions (applied) are based on empirical understandings (contextual values) through a lens of normative judgments (principle values). In addition to clarifying the role of values in governance and management, the framework is envisaged as an analytical tool to assist management practitioners to: 1) elucidate the values operating in a given governance or management setting; 2) tease out how different values influence the aspects of governance and management (e.g. goal setting, assessment, and choosing and applying management strategies), and how those aspects interact to influence outcomes; and 3) to identify potential value conflicts or synergies to guide the integration of multiple environmental interests, priorities and knowledges.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

Human and ecological ‘values’ are becoming increasingly important concepts in environmental governance and management (Tadaki et al. Citation2017; Pascual et al. Citation2023). References to values can be found in contexts ranging from environmental research to management plans and policies (Jones et al. Citation2016; Skewes et al. Citation2017; Tadaki et al. Citation2017). There are emerging suggestions that ‘values’ should become a cornerstone of environmental governance and management (e.g (Tadaki et al. Citation2017; Pascual et al. Citation2023). There is also a general consensus on the need to better account for the diversity of environmental values, including those often overlooked (e.g. cultural, social), or held by often marginalized groups (e.g. local or indigenous communities) (e.g (Arias-Arévalo et al. Citation2018; Chan et al. Citation2018; Christie et al. Citation2019). This has resulted in increased research into developing value concepts, typologies and valuation approaches which aim to better reflect the multiplicity of ways humans value the natural environment (e.g (Arias-Arévalo et al. Citation2018; Chan et al. Citation2018; Christie et al. Citation2019). Accompanied by this is greater interest in the intersection between values, environmental governance and management practice (Jones et al. Citation2016; Tadaki et al. Citation2017; Pascual et al. Citation2023).

Authors have examined links between environmental values, governance or management for some time, and from a broad range of perspectives. Perlman and Adelson (Citation1997) explore the role of values and associated priorities in biodiversity conservation. Norton and Steinemann (Citation2001) highlight the need to account for the diversity of stakeholder values within adaptive ecosystem management. More recent review papers have endeavoured to make sense of the diversity of concepts or approaches used in the applied environmental values literature (e.g. (Jones et al. Citation2016; Tadaki et al. Citation2017), and to examine the contribution values research can make towards understanding and managing human-environment relationships (e.g (Ives and Kendal Citation2014; Jones et al. Citation2016). More specifically, research has demonstrated how valuation can support reaching agreement among stakeholders on management goals (e.g. (Bateman et al. Citation2014; Kenter et al. Citation2016); policy options to be considered (e.g. (Marttunen and Hämäläinen Citation2008; Fish et al. Citation2016); and the means of policy implementation (e.g (Clark and Turpie Citation2014). Approaches or frameworks have also been developed which emphasise values in governance, management or decision-making processes. For example, Kenter et al. (Citation2016) propose a Deliberative Value Formation model for decision-makers to account for a plurality of value perspectives, and to develop shared values in environmental management. Similarly, Norton and Steinemann (Citation2001) present a heuristic model to guide stakeholders toward shared environmental values to underpin adaptive management goals. Other frameworks such as Landscape Approaches also account for values in decision-making and management practice (Sayer et al. Citation2013; Bieling et al. Citation2020).

More recently the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) assessed more than 50,000 scientific publications, policy documents and Indigenous and local knowledge sources on nature’s diverse values and valuation methods to gain insights into their uptake in policymaking (Pascual et al. Citation2023). A key finding was that while valuation methods are diverse and spreading, uptake in policy making remains limited. The authors argue that to increase the likelihood of uptake, policymakers and stakeholders require different types of values information at different stages in the policy cycle – agenda setting, goal formulation, and policy formulation, adoption, implementation, and evaluation. The authors add that learning from one stage feeds back into the design of the next. However, while they highlight the entry points for valuation to inform, aid design or decision-making in the policy cycle and provide some general examples, they do not examine the specifics of which types of value relate to which policy stages or how the values from different stages inform or influence each other. There remains a lack of clarity around which concepts of value relate to the different aspects of governance and management (Tadaki et al. Citation2017), and how governance and management relate to one another more broadly (Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill Citation2015; Bennett and Satterfield Citation2018), including the complex web of conditions (e.g. understanding, communicating, and allocating resources) which reside between, and can create matches and mismatches between the two (Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill Citation2015). Furthermore, much research on environmental values to date is largely inaccessible to environmental practitioners due in part to an emphasis on theory (Ives and Kendal Citation2014; Jones et al. Citation2016), or challenges associated with translating the findings of studies in specific geographical contexts to broader environmental governance and management questions (Ives and Kendal Citation2014). Therefore, there remains a gap between environmental values theory and how associated concepts relate to governance and management practice.

This paper seeks to complement the current body of work by examining the complexities of how different value concepts influence, inform or relate to the different aspects of environmental governance and management, and how those aspects in turn inform each other. We recognise that the concepts of governance and management are complex and contested (Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill Citation2015; Bennett and Satterfield Citation2018). For the purposes of this paper, we confine our discussions to the aspects of governance and management most commonly undertaken by Government actors – namely policy making and implementation. To do this, we 1) review the different value concepts and establish some key value categories; 2) establish some key aspects of environmental governance and management (in the context of policy making and implementation); and 3) present a conceptual framework which maps out the interrelationships between different values and different aspects of governance and management. In addition to helping clarify the role of values in governance and management, the framework is intended as an analytical tool to assist environmental practitioners to:

elucidate the values operating in a given governance or management setting so as to make them more explicit or transparent;

tease out how different values influence the aspects of governance and management, and how those aspects in turn inform each other to influence outcomes; and

identify and reconcile potential value conflicts or synergies which can help guide the integration of multiple interests, priorities and knowledges in environmental management practice.

This paper sits at the intersection of theoretical and analytical approaches. It presents ideas that are grounded in existing theory and attempts to conceptualise how they translate in practice within the day-to-day context of decision making, policy development and planning. We examine the potential utility and limitations of the framework, and its implications for environmental governance and management practice, including integration of multiple interests, priorities and knowledges. These take the form of take away messages for management practitioners.

2. Environmental values – key concepts and distinctions

A broad range of established and emerging approaches to documenting and categorizing human and ecological values exist, all of which come with their own definitions, assumptions, and limitations (Jones et al. Citation2016; Tadaki et al. Citation2017). Ongoing debate exists around the validity of different approaches or categorizations (e.g. relational values - (Luque-Lora Citation2010; Norton and Sanbeg Citation2021). It is important to point out that the purpose of this paper is not to contribute to theory around documenting or eliciting values, but instead to examine how established value types relate to governance and management practice. While any taxonomy of values can lead to insights, no given set of categories will be helpful in all situations (Norton and Sanbeg Citation2021). Where it assists in translating values theory into governance and management practice, we have modified, adapted or expanded upon certain established value categories.

The terms value or values are often used without rigorous definition or a clear link back to the environmental governance or management context in which they are situated (Perlman and Adelson Citation1997; Bentrupperbäumer et al. Citation2006). This poses a significant challenge in establishing the difference between the values which underpin worldviews, goals, or objectives; an object, place, quality or relationship of value; and the reasons why something is valued (Gee et al. Citation2017; Pascual et al. Citation2017; Islar et al. Citation2022). It is important therefore to make a clear distinction between the different ways values have been conceptualized in different disciplines and contexts, to provide a common framework upon which to examine the interrelationship between values, governance and management.

Environmental values can be divided into three broad categories within current values theory. The first type relates to generic environmental values held by individuals or groups which are independent of context or place, which we term as ‘principle values’. The second type of value refers to those that relate to a specific context or location, which we term as ‘contextual values’. Finally, the third type reflect lived experiences, known as ‘relational values’ (Schroeder Citation2013; Jones et al. Citation2016; Tadaki et al. Citation2017), which can take the form of both principle or contextual values, and in practice link the two concepts (Chan et al. Citation2018; Gould et al. Citation2019). We examine these in detail below.

2.1. Principle values

Generic environmental values relate to ideas or principles associated with nature or society that individuals or groups hold as important. When commentators refer to this meaning, they typically write of values in the plural (Perlman and Adelson Citation1997). This broad conceptualisation of values has been examined and described from several perspectives; and referred to as transcendental values (Schwartz and Bilsky Citation1987), held values (Brown Citation1984) or principle-based values (Sagoff Citation1998). Transcendental values are conceptions about desirable end states or behaviours that transcend specific situations and guide selection or evaluation of behaviour and events (Schwartz and Bilsky Citation1987). Held values represent ideals of what is desirable (Bengston Citation1994), how things ought to be, and how one should interact with the world (Brown Citation1984). Principle-based values relate to moral considerations regarding the ‘means’ with which an action or decision is achieved (Sagoff Citation1998; Hirons et al. Citation2016).

For the purposes of clarity and brevity we adopt the term principle values (adapted from Sagoff (Citation1998): principle-based). This is because in the context of public policy making and implementation, values in this sense essentially relate to principles guiding how humans should relate to the natural environment and one another. While this may introduce new terms to what is already a cluttered theoretical space, we think it is justified for the purposes of conveying the concepts in a way which can be best understood by management practitioners who may not be versed in values theory.

Principle values are not necessarily made explicit (Frey Citation1994) and are often latent where related to the environment (Niemeyer Citation2004). Yet an individual, group and indeed a governance process interprets all information or experiences through the lens of their pre-existing principle values. The principle values of an individual or group (i.e. shared social values or norms) are developed through socialization, experiences and the context in which they are situated. Principle values however may be subject to change with every important experience that impinges on them (Perlman and Adelson Citation1997).

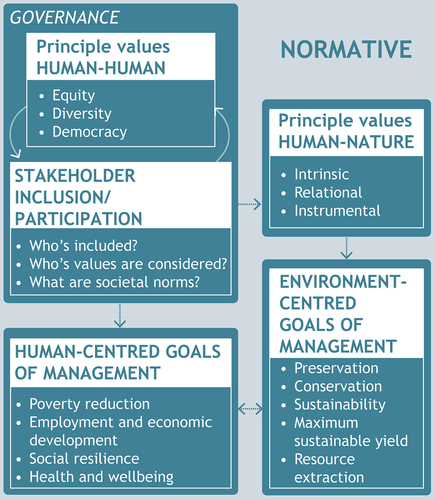

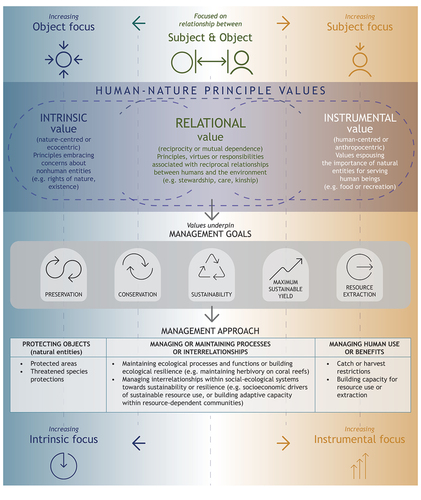

We divide principle values into two broad categories: human-human principle values – associated with principles guiding how humans relate to one another, and human-nature principle values – associated with how humans relate to the natural environment. outlines the key categories of human-human and human-nature principle values. Human-human principle values can be further divided into two categories: egoistic values associated with self enhancement, and altruistic values associated with concern for the welfare and fair treatment of other human beings (Stern et al. Citation1998; Bouman et al. Citation2018). The latter includes the key aspects of equity, diversity and democracy (Saunders et al. Citation2020) (). Human-nature principle values can be divided into three categories, intrinsic, instrumental and relational (Chan et al. Citation2016) (). Intrinsic values, referring to the inherent worth of an organism independent of its value to anyone or anything (Norton Citation2000), have long guided environmental management especially for protected areas (Arias-Arévalo et al. Citation2017). In contrast, instrumental values, where nature serves as an instrument to fulfil human material needs, have been widely used in economic valuations of ecosystems (Chan et al. Citation2016; O’Connor and Kenter Citation2019). Relational values which have emerged more recently, refer to principles, preferences and virtues associated with relationships between humans and the environment (examined in detail in section 2.3). A key component of relational human-nature principle values is reciprocity which emphasises mutual dependence and responsibility between humans and nature, including concepts such as stewardship or care (Chan et al. Citation2018; Ojeda et al. Citation2022). The principle of human-nature reciprocity is a core element of many Indigenous people’s worldviews about nature (Gould et al. Citation2019; Ojeda et al. Citation2022). Whereas intrinsic values of nature are inherent to a natural entity, and instrumental value implies one-directional flow of benefits (value of nature for humans), relational values concern relationships that are reciprocal (Mattijssen et al. Citation2020). With this, it is recognized that humans and nature also shape and influence each other (Gould et al. Citation2019).

Table 1. Categories of principle values associated with how humans relate to one another (human-human) and the natural environment (human-nature).

2.2. Contextual values

In contrast to principle values; contextual values (Kenter et al. Citation2015), which are also referred to as assigned (Brown Citation1984), or preference-based values (Sagoff Citation1998; Raymond et al. Citation2010) involve judgements about worth or importance which are dependent on a specific object of value and are hence contextual and attitudinal (Kenter et al. Citation2015). When commentators refer to this meaning, they typically write of value in the singular (i.e. as of value) (Perlman and Adelson Citation1997). Brown (Citation1984, p. 236) defined this type of value as ‘the expressed relative importance or worth of an object to an individual or group in a given context’. For the purpose of clarity, we adopt the term contextual value (Kenter et al. Citation2015) as it denotes reliance on a specific place or object.

In environmental management, contextual values are assigned to certain places, species, or other features of the natural world and are typically found in economic, ecological or social valuation studies (Seymour et al. Citation2010). We divide contextual values into three aspects, including: a) qualities or attributes exhibited – e.g. species or habitat diversity, resource abundance or environmental health or condition; b) uses supported or benefits provided – e.g. food, water or materials, recreation or climate regulation; and c) relationships enabled – e.g. culture and way of life, maintaining traditions, biocultural interactions or cultural landscapes (i.e. relational values, see section 2.3).

It is important to highlight that the above aspects overlap and inform each other (Escobar Citation1999). For example, fishing may provide food and income (uses or benefits), represent a particular culture and way of life (relationships), and be reliant on the environment exhibiting abundant fisheries resource and intact fisheries habitat (attributes or qualities) (Kuster Citation2011). Contextual values are shaped by principle values and are also influenced by other factors, including socialization processes, knowledge and perceptions, contextual factors, and the characteristics of the resource valued (Seymour et al. Citation2010). Different principle values will lead one to assign importance to different aspects of nature and have different preferences for its condition (Perlman and Adelson Citation1997). For example, intrinsic human-nature principle values correspond with importance placed on attributes such as species diversity or rarity, and an emphasis on minimizing human interaction or impact (Kremen and Ostfeld Citation2005).

2.3. Relational values

It is increasingly recognized that a fundamental basis of concern for nature is based on the relationships that humans have with nature and more than human entities: relational values (Chan et al. Citation2018). Despite some contention as to the appropriateness of relational values as a distinct value category (Luque-Lora Citation2010; Norton and Sanbeg Citation2021), the concept is increasingly applied in a broad range of environmental settings (Mattijssen et al. Citation2020). Relational values have been defined as ‘[linking] people and ecosystems via tangible and intangible relationships to nature [and referring to] the principles, virtues and notions of a good life’ (Klain et al. Citation2017). Relational values can encompass relationships between humans and nature, between different natural entities, or between different human aspects (Chan et al. Citation2018; Schulz and Martin-Ortega Citation2018). Here we are concerned with the first two (). The latter, human-human relational values are examined broadly under human-human principle values (section 2.1). In relational values, the relationships themselves are of value – that is, the value of the relationship between a person and a tree is not found in either the person or tree, but in the connection between the two (Mattijssen et al. Citation2020). In addition, relational values are non-substitutable (Himes and Muraca Citation2018). In so far as the relationship takes on its own meaning as more than a means to an end, and the thing is not wholly substitutable (e.g. a tree planted to commemorate a birth or death) the value is relational (Himes and Muraca Citation2018; Knippenberg et al. Citation2018).

Table 2. Categories of relational value.

Relational values relate to both principle and contextual values but are distinct in that they represent the interdependent relationship between principle and contextual values, cutting across the distinction between the two value concepts (Gould et al. Citation2019). Relational values refer to particular/specific relationships, which are dependent on an object of value and are therefore contextual, yet often play the role of guiding principles – i.e. principle values (Kenter et al. Citation2015; Gould et al. Citation2019). Thus, in a relational context, values can be simultaneously both principle and contextual. In the instance of a person caring for a particular piece of land, that person could simultaneously be guided by the notion that caring for that land is the right thing to do (a guiding human-nature principle value) and influenced by the benefits derived from land management or stewardship e.g. sustained harvests (contextual value) (Gould et al. Citation2019). In the context of real relationships, these two notions of value (principle and contextual) may often be explicitly and inextricably intertwined (Gould et al. Citation2019).

Chan et al. (Citation2018) make the distinction between relational values ‘about nature’ and relational values ‘of nature’. Relational values about nature concern representations of what many people find meaningful about nature (e.g. attachments, commitments, and responsibilities) and correspond with relational human-nature principle values, including care, stewardship and kinship (). Relational values of nature relate to contextual values and are best understood through the concept of eudaimonia or the notion of a good life. Eudaimonic values (a subset of relational values) refer to those contributions to a good life, entailing not only hedonistic dimensions but also living in accordance with moral principles and virtues (Chan et al. Citation2018) (). In the context of relational values, eudaimonic values are concerned with the relationships with nature that contribute towards a good life (Chan et al. Citation2018). Whereas a principle relational value might be responsibility toward a wild mushroom patch, a linked contextual relational value would be the multi-faceted contribution that harvesting mushrooms makes to a good life (e.g. by connecting one to the land, maintaining traditions, motivating a relaxing and contemplative activity) (Chan et al. Citation2018).

We propose that a third type of relational value relevant to environmental management practice be distinguished: process-relational values (). We adapt the term from Mancilla García et al. (Citation2020) who examines the potential of process-relational perspectives in tackling the challenges of social-ecological systems research. This category aims to encompass broader scale dynamics or interrelationships within and between social and ecological systems, in line with the increasing emphasis placed on coupled social-ecological systems in environmental management (Folke et al. Citation2016). The inclusion of process-relational values allows for inclusion of not just relationships between humans and nature, but also relationships between different natural entities, biotic and abiotic.

A process-relational perspective focuses attention on processes, as opposed to objects, as the primary constituents of reality. Processes can be understood as patterns and their properties and functions are defined by the set of relations that constitute them (Mancilla García et al. Citation2020). Emerging from this perspective are then a range of processes or relations between abiotic, biotic or human entities that are of value (). These can be broken up into two broad categories. The first category is ecological processes and functions which underpin the persistence of habitats and species and their resilience to disturbance (Bennett et al. Citation2009). The second, social-ecological relationships – includes interdependent and dynamic relationships between people and ecosystems which support both human well-being and the sustainable management of natural resources (Gain et al. Citation2020; Ojeda et al. Citation2022).

3. Environmental governance and management – the context of public policy making and implementation

Before exploring how values interact with environmental governance and management, it is important to develop some analytical clarity to these concepts and how governance and management differ (Lockwood et al. Citation2010; Bennett and Satterfield Citation2018). The two concepts are not synonymous, instead they are distinct but related. Governance refers to the broader processes and institutions through which societies make decisions that affect the environment. It is generally defined as the institutions, structures, and processes that determine a) who makes decisions, b) how and for whom decisions are made, c) whether, how and what actions are taken and d) by whom and to what effect (Lockwood et al. Citation2010). Management involves operational decisions to achieve specific environmental outcomes (Armitage et al. Citation2012). It refers to the resources, plans, and actions that result from the functioning of governance (Lockwood et al. Citation2010).

The distinction and relationship between governance and management is significant, if not well understood (Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill Citation2015; Bennett and Satterfield Citation2018). In between the two resides the complex web of conditions – understanding, communicating, and allocating power and resources – which can create matches and mismatches between the two (Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill Citation2015). While governance will invariably influence the outcomes of management interventions, management can often be undertaken in isolation of an in-depth examination of its relationship to governance arrangements. This may be due in part to problems in accessing or operationalising important but often highly theoretical governance concepts, theories, or frameworks (Bennett and Satterfield Citation2018). There is a need for practical and pragmatic guidance for practitioners who might wish to apply governance concepts, theories, or frameworks to help ameliorate real-world environmental problems (Bennett and Satterfield Citation2018).

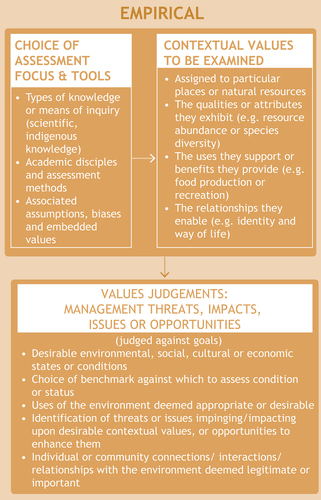

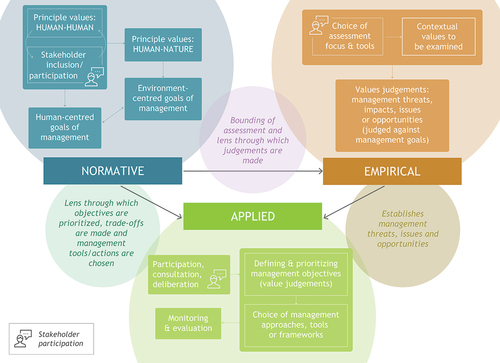

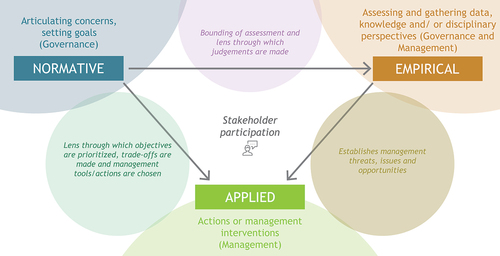

To examine the role of values in environmental governance and management we use the context of Government led public policy making and implementation. For the purposes of this paper, we build upon the broad categories proposed by Voyer et al. (Citation2021) which incorporate both governance and management. Voyer et al. (Citation2021) established three key aspects or focus areas of integrated ocean management: normative, empirical and applied. We have adopted this categorisation to apply more broadly to different aspects of environmental governance and management (). The broad categories provide a useful umbrella to examine and describe the key interactions between values, governance and management. In addition, we adapt and incorporate components of the adaptive management framework for policy making and implementation (Rist et al. Citation2013) to examine the specific interactions occurring within these broader aspects (normative, empirical and applied). These components include: stakeholder inclusion and participation; goal setting; assessment; defining and prioritizing management objectives; choice of management approaches and tools; and monitoring and evaluation. These components while described differently, share significant overlap with the stages of the policy cycle outlined by Pascual et al. (Citation2023).

Figure 1. Broad interrelationship between the different aspects of environmental governance, management and values.

The normative aspect is aligned to governance, although normative goals are inherent, if not always explicit, within management. Normative considerations set the agenda by establishing the ‘rules of the game’ of the decision-making process, stakeholder inclusion and participation, and the overarching goals for management (e.g. environmental, economic, social, cultural). Empirical understandings, knowledge or data are central to both governance and management as they provide a knowledge base for action and decision making relating to the nature and functioning of the environment, and the benefits, impacts or drivers of human use or relationships. Applied aspects are more aligned within management interventions which involve prioritizing or evaluating trade-offs among specific objectives and actions, including allocating use or access, such as protection (e.g. via zoning) or sectoral management arrangements (Voyer et al. Citation2021). The interrelationships between the three aspects are explored in greater detail in relation to values in the proceeding sections.

4. Values in environmental governance and management

Having defined the foundations of our conceptual model, this section will now explore the interrelationships and co-dependencies that exist between governance, management and values within the context of public policy making and implementation. Here we present a conceptual framework which elucidates how different value concepts underpin normative, empirical and applied aspects, and how those aspects in turn inform each other. In short, we argue that management actions (applied) are based on (empirical) understandings through a lens of (normative) judgments (). Through a series of examples, the following sections expand on these interrelationships by; 1) establishing how principle values underpin normative aspects of environmental governance and management; 2) how contextual values underpin empirical aspects of environmental governance and management and are influenced by normative aspects and the values which underpin them; and 3) how the applied aspects of environmental management are influenced by both the empirical and normative aspects.

4.1. Values and the normative aspects of governance

The normative dimensions of environmental governance set the ‘rules of the game’, including the decision-making processes and overarching management goals (Voyer et al. Citation2021). In this section we consider how principle values influence the nature of the management goals that are set and ‘who gets to decide?’ what those goals should be.

It is important first to make a distinction between goals and objectives. Whilst often used interchangeably, there are key differences between these terms. Goals are broad intentions about what one wants to achieve, or general statements about desired outcomes (e.g. conserving biodiversity, sustainable resource use). Objectives are more specific, with the tasks required to achieve the objective outlined in clear terms (Barber and Taylor Citation1990). As goals are broad, they can be intangible (generic), objectives on the other hand are generally tangible targets which you can see and experience (context-dependant) (see section 4.3.1). This places goals higher in order than objectives which are set to achieve goals (Barber and Taylor Citation1990).

4.1.1. Decision making processes underpinned by human-human principle values

The process (or absence of process) for establishing the rules of the game of any governance or management approach is arguably the first and most significant way in which values influence outcomes. Decisions about appropriate and meaningful societal goals are ‘political’ in that the particular goals chosen will have distributive implications for whose interests are realized in environmental decision-making (Tadaki et al. Citation2015). Modern governance and management increasingly recognise the need to engage with participatory models of goal setting, a shift which demonstrates the growing adoption of principle values associated with democracy, equity and diversity (Saunders et al. Citation2020). In contrast, a centralization of power, whereby the rules and goals of governance are established independently of stakeholders, remains a common feature of the governance landscape (Armitage et al. Citation2012). Needless to say, principle values will determine who is included in the management process, whose values are considered and what societal norms will be advanced. We therefore argue that decision-making processes and the nature of public participation are underpinned by human-human principle values (). Human-human principle values adopted at the outset will determine the potential and scope of participation in the process of defining and justifying management goals ().

4.1.2. Management goals underpinned by human-human and human-nature principle values

Any goal that is set finds its roots in a value of some kind (Keeney Citation1996). The question arises ‘which values do environmental management goals reflect?’ (Ives and Kendal Citation2014). The generic nature of management goals mean that they are underpinned by principle values which are not context-dependant (). Human-human principle values often underpin human-centred goals for managing the environment and its use. For example, the goals of poverty reduction, health and wellbeing, or economic development may be underpinned by the value of equitable distribution or access to natural resources. Human-nature principle values influence the goals which govern human-environment relationships or interactions. presents how different human-nature principle values underpin or correspond with different environmental management goals. Human-nature principle values can be conceptualized as a spectrum or continuum with intrinsic (nature-centred or object-focused) values at one end, and instrumental (human-centred or subject-focused) values at the other. Relational principle values associated with reciprocity or mutual dependence (e.g. stewardship or care) fall between these two and focus on the relationship between the subject and the object. Environmental management goals can also be conceptualized as a continuum ranging from preservation at one end to resource extraction at the other end. While recognizing that definitions of conservation, sustainability or maximum sustainable yield vary broadly depending on the context, they serve as a useful illustration of the gradation of management goals between the spectrum of intrinsic to instrumental values (). A focus on purely intrinsic value may correspond most closely with preservation of nature and seeking to prevent all human interaction or impact. For example, a goal of maintaining the persistence of threatened species is likely to be driven by an intrinsic set of values. At the other end of the spectrum a focus on purely utilitarian value could align with the goal of resource extraction, such as in the case of mining where all existing organic and inorganic resources may be entirely removed. In reality, managing the environment usually falls at some point between these two extremes and involves balancing or incorporating both intrinsic and utilitarian values, which are not mutually exclusive, but rather often overlap (Himes and Muraca Citation2018). For example, a coral reef could be protected for both the purposes of conserving biodiversity (intrinsic value) and for mitigating shoreline erosion in adjacent communities (instrumental value).

Figure 3. The relationship between human-nature principle values, environmental management goals and management approaches.

Relational principle values are seen as having the potential to integrate or bridge the gap between intrinsic and instrumental perspectives as they link the subject and the object and position people as part of nature (Chan et al. Citation2018; Mattijssen et al. Citation2020). For example, the value of the relationship between a person and a tree is not found in either the person or tree, but in the connection between the two. With the concept of relational values, humans and nature are therefore not seen as separate entities: humans are part of nature and value their relationship with it (Knippenberg et al. Citation2018). An increasing body of research is indicating that relational values resonate more broadly with environmental stakeholders and provide a more realistic picture of how people value nature (Klain et al. Citation2017; Mattijssen et al. Citation2020). We posit that relational principle values which emphasise reciprocity or mutual dependence between humans and nature (e.g. stewardship or care) align more closely with sustainability concepts and goals (triple bottom line, sustainability pillars, SDGs) which essentially seek to integrate human and environmental interests (unlike intrinsic or instrumental values which tend to favour nature or humans respectively). Accordingly, it appears that they have the capacity to underpin or accommodate a broader range of potential management goals ().

The combination or relative mix of human-centred (human-human principle values) and environment-centred (human-nature principle values) goals chosen will either inform the choice of management framework/model or, conversely, the choice of framework will determine the suit of management goals (and the values underpinning them) to be advanced. For example, it has been argued that SDG 14 – life below water, largely revolves around environmental considerations, falling short of addressing the wide range of socioeconomic issues raised throughout the goal-framing process (Ntona and Morgera Citation2018).

4.2. Empirical aspects of management – underpinned by management goals

The empirical aspect of management involves examining the contextual values of a given social-ecological setting, including the qualities or attributes exhibited; the uses supported, or benefits provided; and the relationships enabled. It also includes examining aspects or activities which impinge on or diminish those values. In most cases this involves some form of assessment, accounting process or inventory of existing knowledge.

In this section we consider two aspects of this process of assessment and the value judgements that are inherent within them (). The first relates to the choice of assessment focus and tools, the second relates to the specific contextual values that are selected to be assessed. Here we define value judgements as decisions or assumptions based on particular underlying principle values.

4.2.1. Choice of assessment focus and tools – contextual values

Environmental assessment is based on numerous choices regarding what should be measured and how it is measured (Grubert Citation2018). Choice of assessment focus and tools are bound explicitly or implicitly by the management goals or aspirations to be advanced, and shape ‘what’s in’ and ‘what’s out’, thereby giving effect to particular framings of environmental management challenges and perhaps unwittingly excluding others (Tadaki et al. Citation2015). For example, if emphasis is placed on achieving economic goals, then focus will be placed on examining the economic benefits (contextual values) of a given social-ecological setting, or aspects which impact on those economic values. A desire for assessments to appear ‘objective’ is common, with results bounded and studies made consistent through guidelines or standards, which imply universally accepted values or absence of values entirely (Grubert Citation2018). However, in practice value-free assessment cannot exist, in part because of the inherent boundary choices required when drawing on multicriteria information (Rosenfeld and Ptolemy Citation2017; Grubert Citation2018). An assessment may be conducted in the absence of an explicitly defined goal, however it will be influenced by the principle values which underpin the discipline or knowledge type in which it is embedded (Kuster Citation2011). Accordingly, choice of an assessment tool does not only influence the type of information to be gathered but may also advance certain underlying goals and associated principle values. Such design choices for assessment reflect the operationalisation of values which may be either implicitly or explicitly articulated (Grubert Citation2018).

4.2.2. Judgement of status, threats, impacts, issues and opportunities

In addition to bounding the scope of assessment, the goals chosen for management will underpin value judgements about which qualities or attributes are desirable, which uses (or intensities of use) are appropriate, and whose relationships are important or legitimate (). The above aspects ultimately shape definition of management status, threats, impacts, issues and opportunities. Assessments of the status of ecosystems or resources require benchmarks (i.e. desired, preferred, or reference states) against which to compare (Anderson Citation1991; Lackey Citation2001). As ecosystems have no preferences about their states, preferred states or benchmarks must come from the individuals or groups doing the assessment (Jamieson Citation1995). The different backgrounds, values and priorities of stakeholders and scientists from different disciplines and management practitioners mean that they may adopt different assessment criteria and interpret resource status differently (Gasparatos Citation2010; Kuster Citation2011). For example, conserving biodiversity as a goal could be assessed using metrics of species composition, rarity, and richness (Margules and Pressey Citation2000). Different ecosystems could be compared and valued according to how much they contribute to realizing the goal of biodiversity conservation according to these metrics (Kremen and Ostfeld Citation2005). In addition, whether a specific use (or intensity of use) is deemed to be detrimental or desirable, will be determined by its contribution to, or impingement on, a specific goal. For example, fishing might be considered a negative impact within a protected area aimed at biodiversity conservation, but a positive activity if aimed at encouraging sustainable livelihoods (Kuster Citation2011).

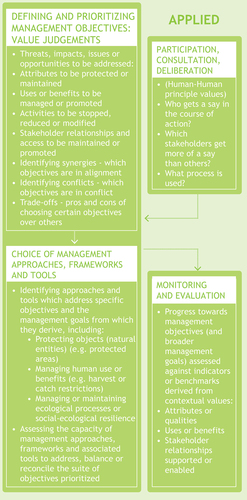

4.3. Applied aspects of governance and management

Applied environmental management involves bringing together normative judgements about what goals a management action is trying to achieve with empirical information and knowledge about the problem, situation or location to be managed, in order to develop a suite of informed and applied management actions (Voyer et al. Citation2021). In this section we consider three common aspects of applied environmental management and their relationship with values. Firstly, we expand on our examination of how the values that underpin normative goals inform the development of management objectives. We then explore how this informs the choice of management approaches, frameworks or tools. Finally, the development of monitoring and evaluation frameworks for management are also linked to clear value judgements about what should be monitored and why.

4.3.1. Defining and prioritizing management objectives – synergies, conflicts and trade-offs

The empirical aspect of management establishes (through a normative lens) the management threats, issues and opportunities associated with a given social-ecological context (section 4.2.2). These form the basis for defining management objectives, including those relating to 1) what attributes are to be protected or maintained; 2) what uses or benefits should be maintained or promoted; 3) which activities should be stopped, reduced or modified; and 4) whose relationships and access should be maintained or promoted.

Once the suite of potential management objectives is identified, value judgements must be made to prioritize them and to identify synergies, conflicts or to assess trade-offs between the objectives. These value judgements are made through a normative lens assessed against the relative mix of human-centred and environment-centred management goals chosen and the principle values which underpin them. Where trade-offs and incommensurability among objectives (and the values which underpin them) occur, questions of power relations among those holding conflicting values may arise (Pascual et al. Citation2017). The normative aspect, in particular the underpinning human-human principle values, will determine which stakeholders get a greater say and the process through which conflicts are addressed or compromise is reached. They will also underpin deliberations around who will carry the costs (impacts of management) and receive the benefits of management intervention.

4.3.2. Choice of management approaches or tools

The suite of management objectives to be advanced or balanced and the broader management goals and underlying principle values which inform them will influence the choice of management approaches or tools (). demonstrates how different management goals and associated principle values underpin or correspond with different management approaches. If we look at the intrinsic value extreme of the spectrum which corresponds with the goal of preservation, we see that this aligns most closely with a management approach focused on protecting objects (natural entities) (e.g. protected areas). If we look at the instrumental value end of the spectrum which could correspond with the goal of resource extraction, we see that this corresponds most closely with a management approach focused on managing human use or benefits (e.g. catch or harvest restrictions). To date little attention appears to have been given to examining how relational principle values which emphasise reciprocity or mutual dependence (e.g. stewardship or care) relate to western management goals and associated approaches. However, we propose that reciprocal values such as stewardship correspond most closely with sustainability goals and management approaches which focus on managing relationships and interactions (interdependencies) between humans and nature; and also between different aspects of nature – a process-relational approach (see section 2.3).

It is important to highlight that while certain management approaches may be adopted to address particular objectives, management approaches or frameworks may in turn favour certain objectives and the broader goals and values which underpin them (Islar et al. Citation2022). For example, protected areas are often used as a framework for advancing ecological, social and economic objectives; however, they may have a predefined emphasis on ecological objectives (biodiversity conservation) which may sideline or deprioritize social and economic objectives (Voyer et al. Citation2021). This goes some way to understanding why new protected areas often result in significant community opposition, reflecting a lack of opportunity and engagement of communities in normative deliberations over management goals and objectives, or if a protected area is the most appropriate tool to achieve these (Voyer et al. Citation2015).

4.3.3. Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation involve assessing progress towards achieving management objectives (and broader management goals) through the use of indicators or benchmarks (Anderson Citation1991; Lackey Citation2001). Similar to environmental assessment, monitoring indicators or benchmarks are underpinned by contextual values, including attributes or qualities, uses or benefits, and stakeholder relationships supported or enabled (i.e. relational values) (). For example, a program concerned with maintaining the sustainability of a coral reef fishery may adopt yield of fisheries resources per unit area of coral reef as an indicator to assess whether management efforts (e.g. catch and effort restrictions) are keeping harvesting within sustainable limits (Kuster et al. Citation2005).

4.4. Synthesis

provides a synthesis of the function and influence of values in environmental governance and management in the context of Government led policy making and implementation. We contend that principle values influence the development and articulation of overarching management goals. These goals will influence the ways in which the situation is assessed and judgements about which environmental ‘problems’ are to be managed, including the contextual values used to identify threats, issues or opportunities. This in turn, will influence how management objectives are defined and the types of management tools and actions employed to deliver these objectives. Values will also define how success is measured or monitored.

5. Discussion and takeaways for management practitioners

The framework presented in this paper seeks to clarify the role of values in environmental governance and management using the context of Government led public policy making and implementation. In addition, it is aimed as an analytical tool to assist management practitioners to elucidate the values operating in a given context, understand their influence, and to identify potential value conflicts or synergies to guide the integration of multiple environmental priorities. We begin by discussing the potential utility and limitations of the framework for elucidating values in environmental governance and management, and the importance of stakeholder participation. We then explore the implications of the framework for governance and management practice. Specifically, we examine how an understanding of the interaction of values, governance and management can inform identification of potential conflicts between, or guide alignment of, the normative, empirical and applied aspects, and the potential of relational principle values emphasizing human-nature reciprocity for integrating multiple environmental interests and priorities. These take the form of take away messages for management practitioners.

5.1. Making values transparent in environmental governance and management

5.1.1. Potential utility and limitations of the framework

A key challenge for environmental governance and management is to accommodate, balance or reconcile the multitude of interests, priorities, knowledges or perspectives of stakeholders involved in use or management of environmental spaces (e.g (Stephenson et al. Citation2021). Underpinning these aspects are values, which need to be made transparent to effectively guide integration (Tadaki et al. Citation2017; Stephenson et al. Citation2021). We feel that the framework provides a structure which could act as a series of prompts or questions to systematically assess the values operating within a governance or management context. For example, one could examine the contextual values and assessment criteria comprising empirical investigations, including judgments of management status, threats, issues, or opportunities. These could then be interrogated to determine the normative principle values which underpin them to shed light on whether the assessments are in alignment with stated governance aspirations. The framework could also be used to interrogate whether the value basis of governance aspirations (e.g. instrumental or reciprocal human-nature principle values) reflect, or have the capacity to integrate, the range of stakeholder aspirations and associated principle values (see section 5.3). In addition, it could be used to examine competing knowledge claims around environmental status and management issues to be addressed, which are often not about the quality or validity of different assessment types, but are instead the result of underlying value differences, associated management goals and assessment criteria (Kuster Citation2011; Grubert Citation2018).

It is important to point out that the framework represents a simplification of governance and management, which in practice is more complicated, nuanced and context specific (e.g (Rist et al. Citation2013). The authors of this paper are academics with practical experience working within public environmental governance and management institutions. One of the authors is also an Indigenous Australian academic with a background in community organisations. Accordingly, the intersection between values and environment governance was examined in the context of public policy making and implementation. However, we acknowledge that this is a relatively narrow focus of environmental governance which does not adequately capture alternative or traditional governance approaches found in a range of cultures. By drawing attention to the role of values in the dominant Government led models of governance found in industrialised countries we hope however to assist in identifying possible pathways towards better alignment of, or appreciation of, diverse governance systems. In addition, the generic examination of environmental values encompassed the principles underpinning many indigenous or traditional governance and management approaches, namely, a relational perspective (relational values) (Gould et al. Citation2019), and more specifically the principle value of reciprocity (Ojeda et al. Citation2022). This has provided some insight into the implications of these values for western governance and management (see section 5.3).

Whilst we maintain that the framework has assisted in clarifying the role of values in governance and management, and provided insights for management practice, it is yet to be applied as an analytical tool. Where possible we expand on key aspects of the framework through illustrative examples, however the scope of this paper remains conceptual and untested. Therefore, this paper sits in the space between theoretical and analytical research, and we hope it provides a pathway through which to bridge the divide between these bodies of work. Future research will expand on this work to empirically apply the conceptual framework to case study examples of environmental governance in practice.

5.1.2. Values derive from humans – participation is central

To ensure broad support for and hence the ongoing sustainability of management interventions, it is important that the values of different stakeholders be made transparent (Tadaki et al. Citation2015; Grubert Citation2018). Environmental values and stakeholder participation are inextricably linked (Tadaki et al. Citation2017), and participation is relevant to all aspects of normative, empirical and applied environmental governance and management. Tadaki et al. (Citation2017) propose that environmental values be viewed as ‘technologies of participation’. The key aspects or junctures where participation has the greatest influence on the values to be advanced include:

establishing the governance principles, decision making processes and governance models;

defining the management goals;

choice of assessment focus, knowledges and tools; and

defining and prioritizing objectives, examining trade-offs, and choosing management approaches, frameworks or tools in all applied aspects.

Importantly, there are links between human-human principle values and procedural aspects of governance, particularly in relation to stakeholder participation. Normative principles of democracy, equity or diversity may be undermined in practice by centralized approaches to developing, deciding upon and implementing management strategies and actions. These values will drive the extent to which a governance process is seen as legitimate within the eyes of stakeholders (Breakey Citation2021).

5.2. Accounting for the interaction of values, governance and management

5.2.1. Establishing normative goals: the importance of reconciling values at the outset

The framework demonstrates how the normative aspect of environmental governance effectively sets the parameters and scope of a management intervention and influences both empirical and applied outcomes. As such, efforts should be made at the outset to examine the source and nature of environmental and societal goals (Tadaki et al. Citation2015), the principle values which underpin them, and to identify conflict and establish common ground between them. Being cognisant of the underlying value basis of management goals is particularly important when potential incompatibilities arise (such as managing for human use of biodiversity as well as conservation goals) (Ives and Kendal Citation2014). Establishing common or shared principle values and associated goals at the outset will minimize potential conflict in both the empirical and applied aspects by establishing consistency on what should be assessed (empirical tools and contextual values) and establishing agreed or consistent benchmarks against which judgements are made regarding management issues, defining and prioritizing management objectives, and choice of management actions or tools.

5.2.2. Knowledge, information and data are influenced by values and context

The knowledge, information or perspectives which underpin environmental decision-making do not exist in a vacuum, instead they are influenced by the context from which they derive (Kuster Citation2011). It is important to establish or elucidate the principle values (normative) which underpin both the choice of assessment focus and associated tools/disciplines, and judgements around management threats, issues or opportunities. It is important when adopting empirical frameworks designed to integrate different types of knowledge or perspectives that efforts are made to interrogate the principle values underpinning them, so as to determine potential bias towards advancing certain priorities.

5.2.3. Governance and management: aligning values and application

Without explicit consideration of the role of values, management activities run the risk of a misalignment between the values that underpin the different aspects of governance and management. That is, each aspect could in practice be underpinned by different values causing tensions and inconsistencies across the process. For example, empirical assessments might not measure the contextual values that are needed to ensure the principle values that underpin the normative goals are being realised. Similarly, applied management interventions might undermine normative goals by being more aligned to a different set of principle values than those embedded within the normative goals. This is because applied management tools and frameworks (such as protected areas) may inherently and implicitly prioritise particular principle values (for example intrinsic over instrumental values (e.g. (Voyer et al. Citation2021)). There is therefore a need to interrogate the principle values that underpin popular management frameworks/tools, and to assess whether they have the capacity to integrate different management goals.

5.3. Informing integration – the potential of relational values which emphasize reciprocity and mutual dependence

The principles of diverse Indigenous worldviews often resonate strongly with relationality and relational value concepts, both in terms of general frames and specific articulations (Gould et al. Citation2019). There are many examples in history and across cultures of diverse human – nature relationships, where reciprocity is a core element of people’s worldviews about nature, which position humans as part of nature (Ojeda et al. Citation2022). The principle of human-nature reciprocity is practiced by many Indigenous and local communities in range of settings – land and sea or urban, rural, and peri urban, even if those efforts are not always recognized (Ojeda et al. Citation2022).

Our examination of how relational principle values which emphasise human-nature reciprocity (e.g. stewardship, care or kinship) relate to management goals, indicates that by focusing on the interdependence between humans and nature, they have the potential to reconcile or accommodate a broader range of management goals than intrinsic or instrumental values. In addition, we argue that unlike intrinsic or instrumental values which focus on the content of people’s values (the what) and underpin management goals which emphasise an outcome or end point (e.g. conserving biodiversity, using resources within sustainable limits), relational values such as stewardship, care or kinship focus on conduct and responsibility (the how and why people should relate to nature) with the main outcome being maintenance of the relationship. In theory a range of potential outcomes (e.g. biodiversity conservation, sustainable use) can derive from or be compatible with relational principle values such as stewardship, so long as they are achieved through a relationship underpinned by the principles. We argue that relational values underpinned by reciprocity or mutual dependence are inherently integrative, and support suggestions by Stålhammar and Thorén (Citation2019) of the importance of relational values for the sustainability agenda by acting as boundary objects used to integrate different epistemological or disciplinary perspectives. This supports a growing body of research indicating that relational values provide a link between intrinsic and instrumental value perspectives and resonate more broadly with different sectors of the community (Chan et al. Citation2016; Klain et al. Citation2017; Mattijssen et al. Citation2020).

In a practical sense, relational principle values focused on reciprocity provide a normative foundation to move environmental management towards a process-oriented (Norton Citation2000) or process-relational approach (Mancilla García et al. Citation2020). This means positioning people as part of nature as in the growing emphasis on social-ecological systems approaches (Folke et al. Citation2016), and emphasising management of ecological processes or functions (Bennett et al. Citation2009). Norton (Citation2000) points out that intrinsic and instrumental value theories are directed at the specific content of people’s values (entity-orientation), rather than the real and shared source of those values in nature. He adds that the common factor in all value stances, is nature valued as a multi-scaled system of creative processes. If this is applied to environmental management, the focus would be on the processes that have created and sustained the species/ecosystems that currently exist rather than on the natural entities themselves (Norton Citation2000).

6. Conclusions

To effectively integrate multiple interests, priorities and knowledges it is important to more critically engage with values in environmental governance and management because values influence all aspects of the process. It is envisaged that the framework presented here will assist management practitioners to elucidate and understand how different value types inform each other across the different aspects of environmental governance and management, with management actions (applied) being based on empirical understandings (contextual values) through a lens of normative judgments (principle values). Ideally, environmental governance and management should be informed by a more explicit consideration of values and identification of how management might build on shared or common values. In this regard, participation is key, because it is people who decide on values. Where it is not possible to establish shared or common values at the normative stage, it is important to interrogate and make transparent the normative values that are influencing a given management aspect, or those embedded in governance and management frameworks. It is hoped that this conceptual framework will assist in that process. We point to relational principle values which emphasise reciprocity or mutual dependence as an area for future inquiry into the role they can potentially play in integrating multiple, and often competing, values within environmental governance and management.

Credit author statement

Chris Kuster: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Resources

Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization

Michelle Voyer: Validation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition

Catherine Moyle: Validation, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization

Anna Lewis: Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration

Acknowledgements

This research forms part of the ‘Blue Futures’ keystone project funded by the University of Wollongong’s Global Challenges program. The authors thank Eleanor McNeill for the graphic design services and Freya Croft for her final review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson JE. 1991. A conceptual framework for evaluating and quantifying naturalness. Conserv Biol. 5(3):347–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1991.tb00148.x.

- Arias-Arévalo P, Gómez-Baggethun E, Martín-López B, Pérez-Rincón M. 2018. Widening the evaluative space for ecosystem services: a taxonomy of plural values and valuation methods. Environ Values. 27(1):29–53. doi: 10.3197/096327118x15144698637513.

- Arias-Arévalo P, Martín-López B, Gómez-Baggethun E. 2017. Exploring intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values for sustainable management of social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc. 22(4). doi: 10.5751/es-09812-220443.

- Armitage D, De Loë R, Plummer R. 2012. Environmental governance and its implications for conservation practice. Conserv Lett. 5(4):245–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263x.2012.00238.x.

- Barber WE, Taylor JN. 1990. The importance of goals, objectives, and values in the fisheries management process and organization: a review. North Am J Fish Manage. 10(4):365–373. doi: 10.1577/1548-8675(1990)010<0365:TIOGOA>2.3.CO;2.

- Bateman IJ, Harwood AR, Abson DJ, Andrews B, Crowe A, Dugdale S, Fezzi C, Foden J, Hadley D, Haines-Young R, et al. 2014. Economic analysis for the UK national ecosystem assessment: synthesis and scenario valuation of changes in ecosystem services. Environ Resour Econ. 57(2):273–297. doi: 10.1007/s10640-013-9662-y.

- Bengston DN. 1994. Changing forest values and ecosystem management. Soc Natur Resour. 7(6):515–533. doi: 10.1080/08941929409380885.

- Bennett AF, Haslem A, Cheal DC, Clarke MF, Jones RN, Koehn JD, Lake PS, Lumsden LF, Lunt ID, Mackey BG. 2009. Ecological processes: a key element in strategies for nature conservation. Ecol Manage Restor. 10(3):192–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-8903.2009.00489.x.

- Bennett NJ, Satterfield T. 2018. Environmental governance: a practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis. Conserv Lett. 11(6):e12600. doi: 10.1111/conl.12600.

- Bentrupperbäumer JM, Day TJ, Reser JP. 2006. Uses, meanings, and understandings of values in the environmental and protected area arena: a consideration of “World heritage” values. Soc Natur Resour. 19(8):723–741. doi: 10.1080/08941920600801140.

- Bieling C, Eser U, Plieninger T. 2020. Towards a better understanding of values in sustainability transformations: ethical perspectives on landscape stewardship. Ecosysts People. 16(1):188–196. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2020.1786165.

- Borrini-Feyerabend G, Hill R. 2015. Governance for the conservation of nature. ANU Press. doi: 10.22459/pagm.04.2015.07.

- Bouman T, Steg L, Kiers HAL. 2018. Measuring values in environmental research: a test of an environmental portrait value questionnaire [original research]. Front Psychol. 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00564.

- Breakey H. 2021. Harnessing multidimensional legitimacy for codes of ethics: a staged approach. J Bus Ethics. 170(2):359–373. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04270-0.

- Brown TC. 1984. The concept of value in resource allocation. Land Econ. 60(3):231–246. doi: 10.2307/3146184.

- Chan KMA, Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould R, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain S, et al. 2016. Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 113(6):1462–1465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525002113.

- Chan KM, Gould RK, Pascual U. 2018. Editorial overview: relational values: what are they, and what’s the fuss about? Curr Opin Sust. 35:A1–A7. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.11.003.

- Christie M, Martín-López B, Church A, Siwicka E, Szymonczyk P, Mena Sauterel J. 2019. Understanding the diversity of values of “nature’s contributions to people”: insights from the IPBES assessment of Europe and Central Asia. Sustainability Sci. 14(5):1267–1282. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00716-6.

- Cinner JE, Barnes ML. 2019. Social dimensions of resilience in social-ecological systems. One Earth. 1(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.08.003.

- Clark BM, Turpie JKE. 2014. Analysis of alternatives for the rehabilitation of the lake St Lucia estuarine system.

- Escobar A. 1999. After nature: steps to an antiessentialist political ecology. Curr Anthropol. 40(1):1–30. doi: 10.1086/515799.

- Fish R, Church A, Willis C, Winter M, Tratalos JA, Haines-Young R, Potschin M. 2016. Making space for cultural ecosystem services: insights from a study of the UK nature improvement initiative. Ecosyst Serv. 21:329–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.09.017.

- Folke C, Biggs R, Norström AV, Reyers B, Rockström J. 2016. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol Soc. 21(3). doi: 10.5751/es-08748-210341.

- Frey R. 1994. Eye juggling: seeing the world through a looking glass and a glass pane: a workbook for clarifying and interpreting values. Lanham, Maryland US: University Press of Amer.

- Gain AK, Giupponi C, Renaud FG, Vafeidis AT. 2020. Sustainability of complex social-ecological systems: methods, tools, and approaches. Reg Environ Change. 20(3). doi: 10.1007/s10113-020-01692-9.

- Gasparatos A. 2010. Embedded value systems in sustainability assessment tools and their implications. J Environ Manag. 91(8):1613–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.03.014.

- Gee K, Kannen A, Adlam R, Brooks C, Chapman M, Cormier R, Fischer C, Fletcher S, Gubbins M, Shucksmith R, et al. 2017. Identifying culturally significant areas for marine spatial planning. Ocean Coast Manag. 136:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.11.026.

- Gould RK, Pai M, Muraca B, Chan KMA. 2019. He ʻike ʻana ia i ka pono (it is a recognizing of the right thing): how one indigenous worldview informs relational values and social values. Sustainability Sci. 14(5):1213–1232. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00721-9.

- Grubert E. 2018. Relational values in environmental assessment: the social context of environmental impact. Curr Opin Sust. 35:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.020.

- Himes A, Muraca B. 2018. Relational values: the key to pluralistic valuation of ecosystem services. Curr Opin Sust. 35:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.09.005.

- Hirons M, Comberti C, Dunford R. 2016. Valuing cultural ecosystem services. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 41(1):545–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085831.

- Islar M, Balvanera P, Kelemen E, Pascaul U, Subramanian SM, Nakangu B, Kosmus M, Nuesiri E, de Vos A, Porter-Bolland L. 2022. Methodological assessment report on the diverse values and valuation of nature of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services: chapter 6: policy options and capacity development to operationalize the inclusion of diverse values of nature in decision-making.

- Ives CD, Kendal D. 2014. The role of social values in the management of ecological systems. J Environ Manag. 144:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.05.013.

- Jamieson D. 1995. Ecosystem health: some preventive medicine. Environ Values. 4(4):333–344. doi: 10.3197/096327195776679411.

- Jones NA, Shaw S, Ross H, Witt K, Pinner B. 2016. The study of human values in understanding and managing social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc. 21(1). doi: 10.5751/es-07977-210115.

- Kaltenborn BP, Linnell JDC, Gómez-Baggethun E, Lindhjem H, Thomassen J, Chan KM. 2017. Ecosystem services and cultural values as building blocks for ‘the good life’. A case study in the community of Røst, Lofoten Islands, Norway. Ecol Econ. 140:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.003.

- Keeney RL. 1996. Value-focused thinking: identifying decision opportunities and creating alternatives. Eur J Oper Res. 92(3):537–549. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(96)00004-5.

- Kenter JO, O’Brien L, Hockley N, Ravenscroft N, Fazey I, Irvine KN, Reed MS, Christie M, Brady E, Bryce R, et al. 2015. What are shared and social values of ecosystems? Ecolog Economic. 111:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.01.006.

- Kenter JO, Reed MS, Fazey I. 2016. The deliberative value formation model. Ecosyst Serv. 21:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.09.015.

- Klain SC, Olmsted P, Chan KMA, Satterfield T, Zia A. 2017. Relational values resonate broadly and differently than intrinsic or instrumental values, or the new ecological paradigm. PLOS ONE. 12(8):e0183962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183962.

- Knippenberg L, De Groot WT, Van Den Born RJ, Knights P, Muraca B. 2018. Relational value, partnership, eudaimonia: a review. Curr Opin Sust. 35:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.022.

- Kremen C, Ostfeld RS. 2005. A call to ecologists: measuring, analyzing, and managing ecosystem services. Front Ecol Environ. 3(10):540–548. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2005)003[0540:ACTEMA]2.0.CO;2.

- Kuster C. 2011. In search of common ground: towards a model for the integration of local and scientific perspectives in the selection of community-based marine protected areas. PhD thesis, Lismore, Australia: Southern Cross University. https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/esploro/outputs/doctoral/In-search-of-common-ground/991012820334802368?institution=61SCU_INS.

- Kuster C, Vuki VC, Zann LP. 2005. Long-term trends in subsistence fishing patterns and coral reef fisheries yield from a remote Fijian island. Fish Res. 76(2):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2005.06.011.

- Lackey RT. 2001. Values, policy, and ecosystem health. BioScience. 51(6):437–443. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0437:VPAEH]2.0.CO;2.

- Lockwood M, Davidson J, Curtis A, Stratford E, Griffith R. 2010. Governance principles for natural resource management. Soc Natur Resour. 23(10):986–1001. doi: 10.1080/08941920802178214.

- Luque-Lora R. 2010. The trouble with relational values. Environ Values 32(4):411–431. doi: 10.3197/096327122X16611552268681.

- Mancilla García M, Hertz T, Schlüter M, Preiser R, Woermann M. 2020. Adopting process-relational perspectives to tackle the challenges of social-ecological systems research. Ecol Soc. 25(1). doi: 10.5751/es-11425-250129.

- Margules CR, Pressey RL. 2000. Systematic conservation planning. Nature. 405(6783):243–253. doi: 10.1038/35012251.

- Marttunen M, Hämäläinen RP. 2008. The decision analysis interview approach in the collaborative management of a large regulated water course. Environ Manage. 42(6):1026–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9200-9.

- Mattijssen TJM, Ganzevoort W, Van Den Born RJG, Arts BJM, Breman BC, Buijs AE, Van Dam RI, Elands BHM, De Groot WT, Knippenberg LWJ. 2020. Relational values of nature: leverage points for nature policy in Europe. Ecosyst People. 16(1):402–410. doi: 10.1080/26395916.2020.1848926.

- Niemeyer S. 2004. Deliberation in the wilderness: displacing symbolic politics. Env Polity. 13(2):347–372. doi: 10.1080/0964401042000209612.

- Norton BG. 2000. Biodiversity and environmental values: in search of a universal earth ethic. Biodivers Conserv. 9(8):1029–1044. doi: 10.1023/A:1008966400817.

- Norton BG, Steinemann AC. 2001. Environmental values and adaptive management. Environ Values. 10(4):473–506. doi: 10.3197/096327101129340921.

- Norton B, Sanbeg D. 2021. Relational values: a unifying idea in environmental ethics and evaluation? Environ Values. 30(6):695–714. doi: 10.3197/096327120X16033868459458.

- Ntona M, Morgera E. 2018. Connecting SDG 14 with the other sustainable development goals through marine spatial planning. Mar Policy. 93:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.06.020.

- O’Connor S, Kenter JO. 2019. Making intrinsic values work; integrating intrinsic values of the more-than-human world through the life framework of values. Sustainability Sci. 14(5):1247–1265. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00715-7.

- Ojeda J, Salomon AK, Rowe JK, Ban NC. 2022. Reciprocal contributions between people and nature: a conceptual intervention. BioSci. 72(10):952–962. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biac053.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Anderson CB, Chaplin-Kramer R, Christie M, González-Jiménez D, Martin A, Raymond CM, Termansen M, Vatn A, et al. 2023. Diverse values of nature for sustainability. Nature. 620(7975):813–823. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06406-9.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Díaz S, Pataki G, Roth E, Stenseke M, Watson RT, Başak Dessane E, Islar M, Kelemen E, et al. 2017. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach. Curr Opin Environ Sustainab. 26-27:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006.

- Perlman D, Adelson G. 1997. Biodiversity: exploring values and priorities in conservation. doi: 10.1002/9781444313550.

- Raymond CM, Fazey I, Reed MS, Stringer LC, Robinson GM, Evely AC. 2010. Integrating local and scientific knowledge for environmental management. J Environ Manag. 91(8):1766–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.03.023.

- Rist L, Campbell BM, Frost P. 2013. Adaptive management: where are we now? Environ Conserv. 40(1):5–18. doi: 10.1017/s0376892912000240.

- Rosenfeld JS, Ptolemy R. 2017. Trade-offs and the importance of separating science and values in environmental flow assessment. Can Water Resour J/Revue canadienne des ressources hydriques. 42(1):88–96. doi: 10.1080/07011784.2016.1211036.

- Sagoff M. 1998. Aggregation and deliberation in valuing environmental public goods: a look beyond contingent pricing. Ecol Econ. 24(2–3):213–230. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00144-4.

- Saunders F, Gilek M, Ikauniece A, Tafon RV, Gee K, Zaucha J. 2020. Theorizing social sustainability and justice in marine spatial planning: democracy, diversity, and equity. Sustain. 12(6):2560. doi: 10.3390/su12062560.

- Sayer J, Sunderland T, Ghazoul J, Pfund J-L, Sheil D, Meijaard E, Venter M, Boedhihartono AK, Day M, Garcia C, et al. 2013. Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 110(21):8349–8356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210595110.