Abstract

In March 2011, the Myanmar Government transitioned to a nominally civilian parliamentary government, resulting in dramatic increases in international investments and tenuous peace in some regions. In March 2015, Community Partners International, the Women’s Refugee Commission, and four community-based organisations (CBOs) assessed community-based sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in eastern Myanmar amidst the changing political contexts in Myanmar and Thailand. The team conducted 12 focus group discussions among women of reproductive age (18–49 years) with children under five and interviewed 12 health workers in Kayin State, Myanmar. In Mae Sot and Chiang Mai, Thailand, the team interviewed 20 representatives of CBOs serving the border regions. Findings are presented through the socioecological lens to explore gender-based violence (GBV) specifically, to examine continued and emerging issues in the context of the political transition. Cited GBV includes ongoing sexual violence/rape by the military and in the community, trafficking, intimate partner violence, and early marriage. Despite the political transition, women continue to be at risk for military sexual violence, are caught in the burgeoning economic push–pull drivers, and experience ongoing restrictive gender norms, with limited access to SRH services. There is much fluidity, along with many connections and interactions among the contributing variables at all levels of the socioecological model; based on a multisectoral response, continued support for innovative, community-based SRH services that include medical and psychosocial care are imperative for ethnic minority women to gain more agency to freely exercise their SR rights.

Résumé

En mars 2011, le Gouvernement du Myanmar a fait la transition vers un régime théoriquement de type parlementaire civil, aboutissant à des augmentations spectaculaires des investissements internationaux et à une paix fragile dans certaines régions. En mars 2015, Community Partners International, la Women's Refugee Commission et quatre organisations communautaires ont évalué les services communautaires de santé sexuelle et reproductive au Myanmar oriental, au beau milieu des contextes politiques changeants au Myanmar et en Thaïlande. L'équipe a mené 12 discussions par groupes d'intérêt avec des femmes en âge de procréer (18–49 ans) ayant des enfants de moins de cinq ans et s'est entretenue avec 12 agents de santé dans l'État de Kayin, au Myanmar. À Mae Sot et Chiang Mai, en Thaïlande, l'équipe a interrogé 20 représentants d'organisations communautaires desservant les régions frontalières. Les conclusions sont présentées dans une perspective socioécologique pour étudier spécifiquement la violence sexiste et pour examiner les problèmes persistants ou émergents dans le contexte de la transition politique. Les actes de violences sexistes cités incluent des violences sexuelles/des viols par des militaires et dans la communauté, la traite, la violence de la part du partenaire intime et le mariage précoce. En dépit de la transition politique, les femmes continuent d'être à risque de violences sexuelles perpétrées par les militaires, sont prises au piège des facteurs économiques naissants de l'offre et de la demande et connaissent des normes de genre restrictives, avec un accès limité aux services de santé sexuelle et reproductive. Il y a beaucoup de fluidité, parallèlement à de nombreuses connexions et interactions entre les variables qui contribuent à tous les niveaux du modèle socioécologique. Sur la base d'une réponse multisectorielle, la poursuite du soutien à des services communautaires et novateurs de santé sexuelle et reproductive incluant des soins médicaux et psychosociaux est impérative pour que les femmes issues de minorités ethniques acquièrent des capacités accrues d'exercer librement leurs droits sexuels et reproductifs.

Resumen

En marzo de 2011, el Gobierno de Myanmar pasó a ser nominalmente un gobierno parlamentario civil, lo cual produjo drásticos aumentos en inversiones internacionales y paz tenue en algunas regiones. En marzo de 2015, Community Partners International, la Comisión de Mujeres Refugiadas y cuatro organizaciones comunitarias (OC) evaluaron los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) a nivel comunitario en el este de Myanmar, en contextos políticos cambiantes en Myanmar y Tailandia. El equipo realizó 12 discusiones en grupos focales con mujeres en edad reproductiva (de 18 a 49 años) con hijos menores de cinco, y entrevistó a 12 trabajadores de salud en el estado de Kayin, en Myanmar. En Mae Sot y Chiang Mai, en Tailandia, el equipo entrevistó a 20 representantes de OC que atendían las regiones de la frontera. Se presentan los hallazgos a través de la perspectiva socioecológica para explorar la violencia de género (VG) en particular, para examinar continuos y emergentes asuntos en el contexto de la transición política. La VG citada abarca continua violencia sexual/violación perpetrada por militares y en la comunidad, trata de personas, violencia de pareja y matrimonio precoz. A pesar de la transición política, las mujeres aún corren riesgo de sufrir violencia sexual perpetrada por militares, se encuentran atrapadas en florecientes impulsores económicos incitadores y disuasivos, y están sujetas a continuas normas de género restrictivas con acceso limitado a servicios de SSR. Hay mucha fluidez, así como muchas conexiones e interacciones entre las variables contribuyentes en todos los niveles del modelo socioecológico. A raíz de la respuesta multisectorial, el continuo apoyo de innovadores servicios de SSR comunitarios, que incluyen atención médica y psicosocial, es imperativo para que las mujeres de minorías étnicas adquieran más agencia para poder ejercer libremente sus derechos sexuales y reproductivos.

Introduction

Myanmar’s ethnic minority border regions have experienced conflict and military activity for seven decades. In March 2011, the Myanmar Government transitioned to a nominally civilian parliamentary government, resulting in dramatic increases in international investments and a tenuous peace in some regions.Citation1,Citation2 In October 2015, the Myanmar Government and eight ethnic armed groups signed a ceasefire agreement.Citation3 The following month, the League for Democracy was democratically elected.Citation4 While the changing political context has resulted in government-led initiatives to broaden access to health care, including sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, how political changes have affected women’s experiences around gender-based violence (GBV) and access to services are unknown.Citation5,Citation6

In March–April 2015, a research consortium comprising Community Partners International (CPI), the Women’s Refugee Commission (WRC), Mae Tao Clinic (MTC), Burma Medical Association (BMA), Back Pack Health Worker Team (BPHWT), and Karen Department of Health and Welfare (KDHW), supported by public health researchers from the United States (US), undertook a qualitative assessment to examine ongoing and emerging gaps and barriers to accessing SRH care in Kayin State, eastern Myanmar. This paper examines findings related to women’s experiences with GBV and access to services, to explore what has changed and what remain as ongoing issues in the context of the political transition.

Theoretical framework

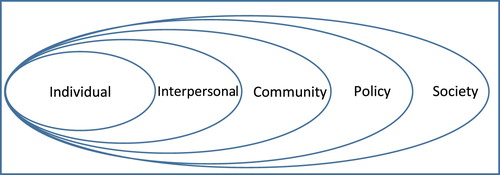

This study draws on the socioecological framework, first promoted by Lori Heise in 1998, to better understand the complex relationships that exist between individuals and their surrounding environment that promote or perpetuate violence in humanitarian settings.Citation7 While variability exists among researchers on how they characterise the different layers of influence, these can include the individual, interpersonal, community, policy, and societal levels. The immediate levels examine factors such as personal security, access to and control of resources, personal relationships, and existing power dynamics between individuals. The community level encompasses the interactions between people within the structures that are influenced by social norms, such as health facilities and security structures. The policy level characterises the legal and political context, while the societal represents cultural and social norms around gender.Citation7,Citation8

In humanitarian settings, conflict or political violence can further impact the various layers of the socioecological framework, as well as amplify the significance of structural or intentional violence. Multiple studies and inter-agency guidelines note the relationship between conflict and the increased risks of GBV for women and adolescent girls, especially.Citation9,Citation10 Several authors have applied the socioecological framework to understanding GBV in crisis and low resource settings, including Hatcher et al. of GBV among pregnant women in rural Kenya; Laisser et al. of intimate partner violence (IPV) in semi-rural Tanzania; and Mootz et al. of GBV among the Karamojong in northern Uganda.Citation8,Citation11,Citation12 These authors found that at the individual level, internalised blame or shame on the part of women, and alcohol consumption on the part of men, contributed to increased risks of GBV. At the relationship level, contributing factors included women’s isolation and lack of social support, transgression of gender roles, and men’s reduced control of resources. At the community level, factors included a lack of responsiveness by the police, stigma, and community resistance to addressing GBV. At the policy and societal levels, inequitable laws and policies, poverty, and pervasive male dominance were found to perpetuate GBV.Citation8,Citation11,Citation12

Much has also been researched about the various forms of GBV experienced by women in the border-based ethnic communities in Myanmar, and existing findings can be placed within the framework of the socioecological model. Fuelled by policy and societal level factors, women’s and human rights organisations within Myanmar have documented a longstanding history of military perpetrated sexual violence in eastern Myanmar.Citation13–20 Despite the 2015 ceasefire agreement, impunity for sexual violence committed by armed actors poses an ongoing and growing threat to women’s safety in the ethnic minority regions.Citation21 In Mae Sot, Thailand, women from Myanmar who are seeking refuge or economic opportunities risk sexual and other forms of abuse from employers, police, and immigration authorities due to their gender and legal status.Citation22–24

Human trafficking remains a further concern. The United States Department of State placed Myanmar on the Tier Two Watch List for the trafficking of ethnic minority women, children, and men from 2012 to 2015 and in 2017.Citation25 In 2016 and 2018, Myanmar was downgraded to Tier Three — a designation reserved for the most problematic offenders.Citation26 Mae Sot, which borders Kayin State (also known as Karen State), is a known location to and through which individuals from Myanmar are trafficked.Citation24,Citation27

Influenced in part by individual-level factors and societal expectations, early marriage is also seen in the region. However, despite the 2014 census finding 12.4% of girls and 4.4% of boys aged 15–19 years being married, early marriage was seldom discussed in the literature.Citation28 Nationally, pregnancy during adolescence most often occurs within marriage, and there is an unmet need for accessible adolescent SRH services.Citation28

IPV has been described as pervasive throughout Myanmar, particularly in ethnic minority areas.Citation29–32 Internally displaced and ethnic minority refugee women cited violence in the home, including rape perpetrated by husbands and restrictive cultural norms that limit opportunities and mobility, as some prominent forms of GBV.Citation23 In a cross-sectional study conducted in three refugee camps along the Thailand-Myanmar border, Falb et al. found 8.6% of women surveyed — the majority being Kayin — experienced IPV, 9.8% conflict-related violence, and 15.4% any form of violence within their lifetime; the last of which was associated with a threefold increase in the odds of experiencing pregnancy complications.Citation33

The literature further acknowledges the fluidity, connections, and interactions among the contributing variables at all levels of the socioecological model. For instance, Mootz et al. found that in the context of domestic physical violence, alcohol consumption as an individual variable was frequently linked with relationship factors that involved resource acquisition as a contributing factor.Citation8 Most of the available literature has been based within conflict or post-conflict settings however, rather than the fluid process of political transition.

Methods

This qualitative assessment was conducted in March-April 2015 to inform existing SRH programming. The research took place in four townships in Kayin State, Myanmar and in Mae Sot and Chiang Mai, Thailand. In Kayin State, the study team selected Hlaingbwe, Kyainseikgyi, Kawkareik, and Myawaddy townships because they were sites for current and future health programming by BMA, BPHWT, KDHW, and MTC. The study conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with village women of reproductive age, as well as semi-structured key informant interviews (KIIs) with village-based health workers and Mae Sot and Chiang Mai-based community-based organisation (CBO) representatives (see ). FGDs were used to learn about village women’s perspectives around health service accessibility, ongoing needs, and perceived service quality. KIIs were used among health workers to learn about their perspectives around demand and gaps in service provision. KIIs with CBO representatives in Mae Sot and Chiang Mai explored CBO perspectives on continued and emerging needs around SRH in the border communities. The study applied similar research methods and study instruments from other qualitative SRH assessments conducted by the WRC.Citation34 The Mae Sot-based Community Advisory Board and the Partners/Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Table 1. Focus groups and interviews by location

The study team implemented 12 FGDs with 8–12 women of reproductive age (18-49 years) in 12 villages in the four townships. Three villages per township were selected based on their varying degrees of access to health services: one with an ethnic health clinic, one far from a clinic, and one close to a government military base. Trained community health workers (CHWs) from BMA, BPHWT, and KDHW conducted the FGDs. The CHWs spoke the local languages, could access remote communities, knew security risks, and could respond to community needs that arose. Several had qualitative research experience through prior CBO research initiatives, and they participated in a five-day training in Mae Sot in March 2015, specifically for this study. Staff from CPI, the US-based researchers, and WRC trained the CHWs in human subjects research, communication skills, facilitation and recording, consent processes, and research ethics. The trained CHWs piloted the study instruments and tools in villages around Mae Sot and Myawaddy prior to data collection under the close supervision of the US-based public health researchers.

In the villages, the trained CHWs recruited women of reproductive age with children under five who likely accessed SRH services, considering age. Recruitment took into consideration political dynamics at the community level and inclusivity across the community. Data collectors facilitated discussions in three languages: S’gaw Kayin, Pwo Kayin, and Burmese. The data collectors obtained informed, verbal consent, which included providing information on participant selection, the nature of the study, and the types of questions asked. Nine of 12 FGDs were audio-recorded; recordings were made only if women individually verbally consented. Given sensitivities around discussing GBV in focus groups, the lack of availability of GBV services in the locations, and the broader focus of the assessment on access to SRH services, women were not directly asked about GBV. Instead, they were asked about perceptions and access to available SRH services, as well as SRH needs more broadly. Participants were not compensated; no personal identifiers were recorded or retained.

The trained CHWs also interviewed one health worker in each village for a total of 12 health worker KIIs. The health workers were selected based on their experiences providing SRH services. Similar processes around language, consent, and confidentiality were applicable, as with the FGDs. While health workers were not asked directly about GBV in the community, they were encouraged to elaborate on community experiences if they mentioned related topics. Nine of the 12 interviews were audio-recorded with the participant’s verbal consent.

In Mae Sot and Chiang Mai, WRC and CPI staff conducted 14 interviews in English with 20 representatives working for cross-border CBOs. These stakeholders were asked to share perceived needs with regard to SRH broadly, and for vulnerable populations in their communities. In addition, stakeholders were asked to comment on issues related to GBV affecting their communities. Verbal consent was also obtained for participation and recording. Thirteen of 14 interviews (some interviews were conducted with two representatives from the same organisation) were audio-recorded with the interviewees’ consent.

The CHWs transported audio recordings and handwritten notes from the villages to Mae Sot in April 2015, where they participated in a three-day debrief and analysis workshop with CPI and CBO staff. The workshop focused on identifying themes, as well as generating preliminary recommendations based on initial findings.

In the subsequent months, CBO staff transcribed the audio recordings in their original language, and translators from BMA and KDHW translated the transcripts into English. The translators compared handwritten notes with transcriptions, adding any missing information. Regarding the CBO interviews, two WRC staff transcribed the English audio files. The recordings were deleted once the data were transcribed. Original notes were stored in a locked cabinet in CPI’s Mae Sot office. Only co-investigator staff involved in the data analysis had access to transcripts.

In terms of data analysis, staff from CPI, WRC, and the US-based researchers coded all of the English transcripts and analysed the data using Dedoose, an online qualitative analytic software.Citation35 Transcripts were coded using a content analysis approach and reviewed by at least two researchers to enhance reliability and reduce variability.Citation36 Codes and descriptive categories relating to SRH and its sub-components were developed using analytic induction after reviewing a subset of transcripts. The codes were subsequently revised for better applicability and applied to the remaining transcripts. The identified codes and themes were further analysed vis-à-vis the socioecological framework to understand GBV in the context of the political transition, and women’s access to services (see ). Findings were further discussed during two stakeholder workshops in Mae Sot. During these meetings, CBO partners confirmed the validity of the results and developed joint recommendations.

Figure 1. Socioecological framework

Note: Adapted from: Terry MS (2014) Applying the Social Ecological Model to Violence against Women with Disabilities. J Women's Health Care 3: 193. doi:10.4172/2167-0420.1000193

Results

Overview of GBV in the community

GBV-related concerns mentioned by study participants included ongoing sexual violence/rape by the military and in the community, trafficking, IPV, and early marriage. CBO representatives in Mae Sot and Chiang Mai discussed GBV, focusing on sexual violence. Village-based health workers in Kayin State spoke about IPV and early marriage, but not other forms of GBV. Of note, women in FGDs made no mention of GBV-related needs when asked in an open-ended manner to cite on-going SRH needs in their communities, or when asked about vulnerable populations. However, they alluded to factors at different levels of the socioecological framework that could be contributing to some of the violence they continue to experience. The data are thus presented through the socioecological lens to explore GBV and women’s access to services to examine what has changed and what remain as ongoing issues in the context of the political transition.

Individual level

The individual level represents factors that affect the individual’s behaviour and relationships, and the immediate context in which the abuse takes place.Citation7 Findings showed that the individual-level factors that were mentioned vis-a-vis GBV were lack of SRH awareness, drugs, and alcohol. These issues were often mentioned as factors that prompted risky sexual behaviour, unintended pregnancy, subsequent unsafe abortions, and marriage at an early age. Other individual-level factors mentioned included shame on the part of survivors that limited access to care.

Limited SRH awareness and early marriage

CBO representatives and health workers raised early marriage as a recurring issue, defined as marriages of girls aged 13–18. One village health worker shared: “Yesterday, a sixteen-year-old girl came to the clinic. But her pregnancy was eight months already after we had examined her. Actually, she is not sixteen yet, but almost delivers a child. Her husband is just fifteen years old.”

CBO representatives and health workers discussed “early marriage” as a social and health concern, and less as a violence issue. CBO representatives noted the decision to marry young often resulted from an unintended pregnancy, resulting in turn from poor SRH knowledge and access to care.

CBO representatives reported a lack of awareness and knowledge around family planning as a major factor that further prompted young married girls to become pregnant soon after marriage, if they were not already pregnant prior to marriage. One CBO representative shared:

“The most important thing is that we need to prevent early marriage. Because in our communities, very young teenage girls, they are married early and don’t know how to prevent pregnancy, or how to use contraceptives or condoms … I saw a young woman. She was only 13 years old. But she was already pregnant … because she didn’t know how to prevent” [pregnancy].

“Mostly it is unsafe abortion. They do by themselves or they go to people who do that, or they will take the medicines from China, and then do the abortion by themselves, and finally they are bleeding and faint [from] serious anaemia. And then they come to clinic, and oh my god. People nearly die.”

Drugs and alcohol

Alcohol – especially in Mae Sot – and illegal drugs, were seen as major contributors to GBV at the individual level; alcohol to IPV and violence against children, alcohol and drugs to adolescent pregnancy and early marriage, and drugs to sexual violence and trafficking. In terms of IPV, a village health worker shared: “Some men only use their income for drinking, and women have many children … Some women go to work even though they have a newborn to take care of to be able to provide food for their children.”

Regarding adolescents, one CBO representative mentioned: “Some adolescents, if they drink alcohol, will try taking the girls in the communities, and in many cases, [this becomes] a social problem. So, one thing is drug problem.” In Mae Sot, adolescent pregnancy was perceived to be more common than early marriage.

Alcohol and illicit drug use were raised as major concerns for individuals and public health at large. The links between drugs and sexual violence and trafficking are elaborated in more detail in the policy level section, given the strong interlinkages between conflict, economic activity, drugs, and GBV.

Shame hindering access to services

CBO representatives explained that those who survive GBV in particular are unlikely to report as a result of a deep sense of shame. As one CBO representative added:

“And, also, the gender-based violence from the other, from the other men, like from the other men in the village, it is like, like torture. Especially for the women. They keep that information very … secret … . Like if, if this information comes out, spreads out, people will look down on them … . they will be ashamed. So, that is a barrier.”

“I know our maternal and child health workers collect information … where gender-based violence happens in their own area. And, they take care … of women who experience violence. But, as I see and know, that kind of information is quite difficult to get, the real information [about] what happened … You cannot get it. Yeah, it gets quiet and disappears.”

Interpersonal level

The interpersonal level focuses on personal relationships and existing inequalities between individuals that can reinforce power dynamics.Citation7 Women and health workers frequently mentioned the role that husbands and other family members play in women’s abilities to exercise their SRH rights and access SRH services.

SRH decisions and autonomy

In villages, CBO representatives and health workers perceived that most IPV cases were of adults and within families. While women in FGDs did not directly voice that their spouses were violent, some women alluded to forced sexual intercourse within marriage, as well as their limited autonomy in the home, especially pertaining to reproductive decisions. One woman from one village noted: “As for me, there are difficulties to prevent from getting pregnant as I am in a family economic crisis and my husband is also not good to me and does as he likes.”

A village-based health worker supported the view that some women may not have the ability to decide whether to use a family planning method: “There are some husbands who do not allow their wives to take them. Some women do not use pills or injections even though they have many children.” Another health worker mentioned:

“Some women were not in good health after they got married. But their husband wants to have a baby. Women do not have any rights to prevent pregnancy by themselves. They have no choice when their husband asks them to become pregnant.”

Mothers-in-law and women’s parents were also mentioned by many FGD participants as influential persons within families that determined health service access for women. This was primarily in the context of pregnancy care, as well as when a woman could seek family planning. A village health worker explained this dynamic:

“Some … have their first baby by being forced by their parents, and then the parents let their children use birth control methods. They worry they will not get their new generation if they let their children first use contraception before they have their first baby.”

Community level

The community level encompasses the interactions between people within the formal and informal structures that are influenced by social norms.Citation7 The two issues raised at this level were the physical environment where non-military sexual violence often takes place in the Mae Sot area, as well as the widespread impunity that still exists around sexual violence and trafficking in particular.

Remoteness

CBO representatives noted that female migrant and factory workers in Mae Sot face risks of sexual violence. In the Mae Sot area, rape among migrant and factory workers was reported primarily in the peri-urban areas, given their remoteness. A CBO representative explained: “Sometimes they walk very far into the remote area, some have no mobile contact, … and [there are] no motorbikes nor any people. Therefore, it is very, very prone to occur – GBV in that remote area.”

Impunity

Ongoing impunity was raised by CBO representatives as contributing to sexual violence and trafficking.

While also a policy level issue, as one CBO representative noted, the political space in eastern Myanmar still has not resulted in legal consequences for perpetrators of sexual violence or empowerment of women and girls: “We cannot do much with the people who traffic and rape because they have power, they have money, so we cannot do much with them. One thing we can do is provide knowledge to the community.”

Among village women and health workers, impunity was discussed more in the context of daily safety at the village level (check points, etc.). CBO representatives also acknowledged the prevailing problems around impunity in cases of sexual violence and trafficking.

Policy level

The policy level encompasses the legal and political frameworks that perpetuate violence.Citation7 In eastern Myanmar, factors that were raised at this level included the continued military presence, increased economic activity prompted by aid infusion and investments, and the continued lack of legal status, all against the backdrop of the political transition. The interactions of these factors presented ongoing GBV risks for women, especially sexual violence and trafficking.

Ongoing military presence and economic impetus

On the whole, village women, health workers, and CBO representatives agreed to decreased insecurity as compared to the period prior to the ceasefire agreement. However, sexual violence was mentioned by CBO representatives and health workers as a form of ongoing violence, especially in the ethnic areas. They most often reported incidents in Kachin and Shan States due to the ongoing conflict in these areas. Perpetrators were reportedly from the Myanmar military, although villagers were sporadically mentioned. Sexual violence was said to increase where the Burmese army was present, as well as in mining, damming, and other zones with economic activities known for “drugs, sex, and disease”. One CBO representative noted: “There is a lot of negative change in our Kachin area. A lot of IDPs [internally displaced people]. And also fighting is ongoing. Women have been raped … those kinds of human rights violations are happening in our Kachin area.”

Another CBO representative summarised:

“The concern areas for the women’s groups that I’ve seen over the past year, I think, one is the militarization in Kachin State right now. Definitely to do with the increase in military presence in the ethnic areas that is creating, is continuing, sexual violence. The other one is development … . when these outside employees come to work on these construction work, then a lot of the women around that construction area are at risk of sexual violence. And it doesn’t seem like there is a lot of, you know, support systems … The jade mining areas of Kachin State, you hear so many people, migrant workers working in jade mines … . The heroin addiction is just, out of this world. There are a lot of sex workers, you know, in places all around that area. And violence and HIV come with that.”

“One is kidnapping. Second is people get a lot of, ‘You will get a lot of money if you come with me and go work.’ … Because now in Shan State, there are lot of conflict zones. Ethnic armed groups collect people into the armies, people trying to escape from this problem come to Thailand trying to seek better opportunities. So, it is one of the things that support trafficking, too … people see these problems and keep going into the community saying that there are better opportunities there, so girls go very easily.”

“Trafficked women have been sexually abused in trafficked situations, and when they come back for survival, sexual and reproductive health counselling and service are very rare … I think some of the people know that it is very important for women, but because of the situation and other challenges, there have been no service at all, yet.”

Societal level

The society level includes cultural and social norms about gender roles, and attitudes towards women and adolescents.Citation7 The study found restrictive gender norms and normalised violence contributing to ongoing IPV; expectations around upholding family and household economies as contributing to early marriage; and perceptions around unmarried adolescents and their use of SRH services as hindering their access to care.

Restrictive gender norms and normalised violence

CBO representatives described domestic violence as “normal” and a common reality with consequences for women and children – a reality that has not changed for Burmese women at this border as Myanmar has attempted to move towards democracy. A CBO representative described: “According to our Burmese tradition, we do not want to talk openly about RH, sex education and also GBV. In our Burmese culture, the husband is the number one person. Therefore, he can do anything.” A village health worker also mentioned, “Husbands do not care about women’s health and beat their wife physically and mentally when they come home from work. They are also uneducated, and women are relying only on their husband’s income.”

Upholding family economies

In addition to unintended pregnancies, CBO representatives reported that early marriage could be a result of choice made out of economic or family considerations. Economic reasons included difficulty in finding work or a lack of money. Family and societal pressures and expectations appeared to contribute to this as mentioned by one CBO representative:

“If the girl or boy grows up, they have to work for money and their families … if they become adolescents, parents will say you will have a family, you have to work, you have to get money for your life, so they all think that and marry early.”

Perceptions around unmarried adolescents’ access to SRH services

FGDs among women revealed that SRH care is not easily obtained by unmarried adolescents at the village level. While some health workers mentioned that young married women come for family planning, unmarried girls often do not seek SRH or family planning services due to shame, shyness, or fear. Quotes from women included: “There aren’t unmarried women who use family planning here. If they are found, people will tell,” and “Women who are not married or single women are looked down upon by the community if they use family planning methods.”

CBO representatives especially commented on the need for SRH programmes targeting adolescents, including new mothers, to prevent unintended pregnancies and their consequences, including early marriage arrangements.

Discussion

Findings from this assessment have identified continued and emerging GBV concerns affecting ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar amidst the changing political, social, and economic climate. Cited GBV includes ongoing sexual violence/rape by the military and in the community, trafficking, IPV, and early marriage. Based on the socioecological lens, at the individual level, primary factors that contribute to ongoing GBV include lack of SRH awareness and drugs and alcohol that lead to violence in the home, risky sexual behaviour, unintended pregnancy, subsequent unsafe abortions, and early marriage. Other individual-level factors include shame on the part of survivors that limit access to care. At the interpersonal level, husbands and other family members continue to influence women’s ability to exercise SRH rights and access SRH services. At the community level, factors raised in this research include the physical environment, as well as widespread impunity that still exists around sexual violence and trafficking in particular. The policy level is characterised by militarisation of economic development zones and the push–pull factors created by migration, mining, and conflict that present ongoing sexual violence and trafficking risks. At the societal level, restrictive gender norms and normalised violence continue to perpetuate IPV; expectations around upholding family and household economies contribute to early marriage; and perceptions around unmarried adolescents and their use of SRH services hinder their access to care. Thus, despite the political transition, women continue to be at risk for military sexual violence, are caught in the burgeoning economic push–pull drivers, and experience ongoing restrictive gender norms, with limited access to SRH services. Democracy has thus yet to change the lived experiences and freedoms for women at this border.

As mentioned in the literature, there is much fluidity, along with many connections and interactions among the contributing variables at all levels of the socioecological model. The factors promulgating the various types of GBV are multifold and disentangling them by level can be challenging. CBO representatives in particular flagged ongoing concerns, and these needs identified in 2015 take on particular urgency given increased economic activity, the breakdown of ceasefires in Kayin State in early 2018, and the rise in conflict and reports of state-sponsored sexual violence in Kachin and Rakhine States over the past year.Citation37–39

Reports of sexual violence in the ethnic minority regions have been documented for decades.Citation13–20 This study found ongoing and emerging risk factors across levels that perpetuate this violence and other forms of GBV, and more recent studies have further examined the intricacies of economic activity and military- and villager-perpetrated violence. For example, a 2012–2016 study from southeast Myanmar documented an ongoing threat of sexual violence by the Myanmar military; alcohol and drug-induced GBV committed by community members; and a heightened risk of GBV for women with low education levels. Access to justice and health services in villages was found to be limited, and women’s protective income generation activities were undermined by development and other actors.Citation40 A 2013 population-based survey in eastern Myanmar additionally reaffirms that migration continues despite the political transition. The primary reasons cited for migration out of the household into even precarious settings was education (46.4%), followed by work (40.2%); which speaks to the economic push–pull factors additionally documented in this study.Citation41

Findings from our study, especially pertaining to family and household influences and decision-makers around women’s SRH, show the possible connections of traditional beliefs and social norms that may still limit women’s and girls’ ability to be free from violence or exercise their SRH rights. The 2013 population-based study has additionally documented women’s sub-standard level of access to SRH care in eastern Myanmar.Citation42 Nevertheless, numerous studies have shown that awareness and sustained interventions can indeed enhance women’s access to contraceptive choice and even abortion care in the border-based communities.Citation43

Our study further found the need for adolescent SRH and some of the normative barriers that unmarried adolescents face in their access to SRH services. A 2018 qualitative study by Asnong et al. of adolescent perceptions and experiences of pregnancy along the Thailand-Myanmar border found that adolescent pregnancy was related to premarital sex, forced marriage, lack of contraception, school dropout, fear of childbirth, financial insecurity, support structures, and domestic violence; all of which are interlinked within the socioecological model.Citation44 A 2017 study by Kågesten et al. of very young Burmese adolescents aged 10–14 also found gaps in SRH information necessary for healthy transitions through puberty. The authors stressed the importance of early SRH interventions that involve parents and educational centres.Citation45 Recent learning from the WRC around early marriage in humanitarian settings additionally shows the importance of providing health care – including family planning services – education, protection, and livelihoods; teaching life-skills and decision-making; and fostering economic literacy in early marriage interventions.Citation34

Since August 2017, violence perpetrated towards the Rohingya community in Myanmar has resulted in widespread displacement and reports of GBV against fleeing populations. Per the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are roughly 900,000 Rohingya refugees in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. To address the humanitarian crisis, in February 2019, UNHCR and the Government of Bangladesh released their 2019 Joint Response Plan. Of the total refugee population, 52% are women and girls. Many of them have been exposed to widespread and severe forms of sexual violence in Myanmar, and they continue to be at disproportionate risk of IPV, forced/child marriage, exploitation, and trafficking. Despite these risks, as of November 2018, only 43% of minimum service coverage has been achieved for GBV case management and psychosocial support. Access to health services for GBV survivors is also limited, with almost 56% of sites lacking required services.Citation46 Against this backdrop, a 2018 qualitative study by the WRC found that Rohingya men and boys are also subjected to GBV, including forced witnessing of sexual violence against women and girls, genital violence – mutilation, burning, castration, and penis amputation – and anal rape, as well as sexual abuse and exploitation. While the disproportionate impact remains on women and girls, care for survivors of GBV is critical for all survivors.Citation47

Given the prevailing risks at all levels – both continued and escalating – the need for multisectoral GBV prevention and response services is paramount.Citation9,Citation10 It is additionally important for health organisations to provide medical and psychosocial care to sexual violence survivors to prevent unwanted pregnancy, HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and other consequences. To address the challenges of ensuring facility-based post-rape care in eastern Myanmar, WRC, CPI, BMA, and KDHW implemented a community-based approach to providing medical care to survivors of sexual violence in Kayin State in 2009–2011. CHWs were trained to provide SRH services according to the 2004 World Health Organization’s minimum protocol to explore whether such a method was safe and feasible. This was the first attempt to task-shift post-rape care. The project built on the MOM Project’s existing SRH logistics framework, a cadre of trained CHWs, community rapport, and monitoring mechanisms for community-based service delivery.Citation30 Revisiting this model in rural Myanmar is critical and timely, as the alternative in remote areas is no post-rape care. Indeed, studies have since explored the potentials, as well as remaining gaps, for the community-based provision of care for survivors of sexual violence.Citation48

Continued support for community-based SRH services that include medical and psychosocial care for survivors of GBV would be expected to increase availability, accessibility, and quality of SRH services in remote villages and contribute to overall health systems strengthening. Village-level systems – especially those that support women and women’s groups – should be leveraged and expanded to protect women and girls in Myanmar.Citation49 Village-level GBV programming may fill critical gaps as conflict and human rights abuses driven by the Myanmar Government rise, and this rising insecurity limits access to geographically distant clinical services. Additionally, health programmes can benefit from linkages with feasible protection, education, and livelihoods components, which help sustain health systems, provide more holistic care, and better address the fluid and interconnected layers of the socioecological model.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study was the research team’s inability to directly interview women in communities with regard to GBV needs given the lack of available response services. The authors also acknowledge that FGDs are not generally appropriate to explore sensitive issues, such as GBV, and it was beyond the scope of the study to include additional data collection methods. Thus, discussions among village women focused on SRH needs and risks more broadly. The findings and conclusions on GBV are therefore inferred from the reports of the health workers and CBO staff.

Time and logistical constraints permitted only three FGDs and three health worker interviews in each township. Accessibility challenges prevented remote supervision of field activities; therefore, the data collector training focused on improving quality. Language difficulties were also present; the training was conducted in four languages and some FGDs were implemented in one language with notes taken in another (due to written Kayin not being taught in many schools). To minimise inaccuracies and loss of data, audio-recorded activities were transcribed verbatim and compared with notes. As the FGD data collectors were CHWs, some participants may have hesitated to voice concerns. However, this was unlikely since negative feedback was noted. Lastly, not every organisation conducting SRH research or services along the border was interviewed, but the majority of and the most relevant CBOs were reached.

Conclusion

An application of the socioecological lens shows the various interlinked and dynamic factors that contribute to ongoing and emerging GBV risks for women in eastern Myanmar against the backdrop of recent political transition. Based on a multisectoral framework, opportunities exist for health CBOs to integrate GBV issues through programming around health, gender, and equitable access to care. Meaningful improvements in GBV experiences for women will need to involve ethnic minority women gaining more agency in Myanmar to be able to freely exercise their SR rights. Given increased conflict in Kayin, Kachin, and Rakhine states, and other regions in Myanmar, developing innovative programming to reach women experiencing GBV in Myanmar is particularly crucial.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to staff at BMA, BPHWT, KDHW, and MTC who contributed to implementation and analysis, and deeply grateful to the Kayin women and representatives in Mae Sot and Chiang Mai who shared their valuable time and perspectives. The authors would like to acknowledge Marisa Felsher, who conducted part of the data transcription.

ORCID

Jennifer Leigh http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6319-4269

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rieffel L, Fox JW. Too much, too soon? The dilemma of foreign aid to Myanmar/Burma [Internet]. Brook. Inst. [cited 2016 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2013/03/03-foreign-aid-myanmar-burma-rieffel.

- Myanmar signs ceasefire with eight armed groups. Reuters [Internet]. 2015 Oct 15 [cited 2018 Oct 11]; Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-politics/myanmar-signs-ceasefire-with-eight-armed-groups-idUSKCN0S82MR20151015.

- The nationwide ceasefire agreement between the government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the Ethnic Armed Organizations [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/MM_151510_NCAAgreement.pdf.

- Farrelly N, Win C. Inside myanmar’s turbulent transformation. Asia Pac Policy Stud. 2016;3:38–47. doi: 10.1002/app5.124

- Lubina M, Sabrie M. Transformation in Burma/Myanmar: economic, social and spatial changes. SOAS, University of London; 2016; Available from: https://www.soas.ac.uk/cseas/aseasuk-conference-2016/file109437.pdf.

- Risso-Gill I, McKee M, Coker R, et al. Health system strengthening in Myanmar during political reforms: perspectives from international agencies. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:466–474. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt037

- United Nations Population Fund. Managing gender-based violence programmes in emergencies e-learning and companion guide [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/GBV%20E-Learning%20Companion%20Guide_ENGLISH.pdf.

- Mootz JJ, Stabb SD, Mollen D. Gender-based violence and armed conflict: a community-informed socioecological Conceptual model from Northeastern Uganda. Psychol Women Q. 2017;41:368–388. doi: 10.1177/0361684317705086

- Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises. Inter-agency field manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://iawg.net/iafm/.

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Guidelines for integrating gender-based violence interventions in humanitarian action: reducing risk, promoting resilience and aiding recovery [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Jul 13]. Available from: http://gbvguidelines.org/.

- Hatcher AM, Romito P, Odero M, et al. Social context and drivers of intimate partner violence in rural Kenya: implications for the health of pregnant women. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15:404–419. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.760205

- Laisser RM, Nyström L, Lugina HI, et al. Community perceptions of intimate partner violence - a qualitative study from urban Tanzania. BMC Womens Health. 2011;11(13).

- Karen Women’s Organisation. State of Terror: the ongoing rape, murder, torture, and forced labour suffered by women living under the Burmese Military Regime in Karen State [Internet]. 2007. Available from: https://karenwomen.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/state20of20terror20report.pdf.

- The Shan Human Rights Foundation, The Shan Women’s Action Network. License to rape: how Burma’s military employs systematic sexualized violence. 2002.

- Women’s League of Burma. Same impunity, same patterns: sexual abuses by the Burma Army will not stop until there is a genuine civilian government [Internet]. 2014. Available from: http://womenofburma.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/SameImpunitySamePattern_English-final.pdf.

- Apple B, Martin V. NO SAFE PLACE: Burma’s army and the rape of ethnic women [Internet]. Washington (DC): Refugees International; 2003; [cited 2015 Jan 30]. Available from: http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs09/No_safe_place_Burmas_army.pdf.

- Meger S. Sexual and gender-based violence in Burma/Myanmar [Internet]. Monash University; 2014; Available from: http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/preventing-mass-sexual-violence-in-asia-pacific/files/2014/10/Sexual-and-Gender-Based-Violence-in-Burma-PSVAP-Report-2014.pdf.

- Pellegrini C. Burma briefing: rape and sexual violence by the Burmese Army [Internet]. Burma Campaign UK; 2014. Report No.: 34. Available from: http://www.peacewomen.org/assets/file/Resources/NGO/rape_and_sexual_violence_by_the_burmese_army.pdf.

- Women’s League of Burma. “If they had hope, they would speak”: the ongoing use of state-sponsored sexual violence in Burma’s ethnic communities [Internet]. Chiang Mai, Thailand; 2014. Available from: http://womenofburma.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/VAW_Iftheyhadhope_TheywouldSpeak_English.pdf.

- Karen Human Rights Group. Dignity in the shadow of oppression: the abuse and agency of Karen women under militarisation [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2016 May 1]. Available from: http://khrg.org/2006/11/dignity-shadow-oppression-abuse-and-agency-karen-women-under-militarisation.

- Women’s League of Burma, Asia Justice and Rights. Access to justice for women survivors of gender-based violence committed by state actors in Burma, Briefing Paper [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 May 26]. Available from: http://www.asia-ajar.org/files/VAW%20Briefing%20Paper-%20English%20Version.pdf.

- Kusakabe K, Pearson R. Working through exceptional space: the case of women migrant workers in Mae Sot, Thailand. Int Sociol. 2016;31:268–285. doi: 10.1177/0268580916630484

- Norsworthy KL, Khuankaew O. Women of Burma speak out: workshops to deconstruct gender-based violence and build systems of peace and justice. J Spec Group Work. 2004;29:259–283. doi: 10.1080/01933920490477011

- Freccero J. Safe Haven: sheltering displaced persons from sexual and gender-based violence; case study: Thailand [Internet]. Human Rights Center, Berkeley Law, University of California; 2013 [cited 2016 May 8]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/51b6e3239.pdf.

- United States Department of State. (2015). Trafficking in persons report [Internet]. 2014. p. 104–107. Available from: http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/245365.pdf.

- United States Department of State. Trafficking in persons report 2016 [Internet]. Department of State. The Office of Website Management, Bureau of Public Affairs.; 2016 [cited 2016 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2016/258696.htm.

- United Nations Inter-Agency Project on Human Trafficking/Myanmar. Strategic information response network (SIREN) human trafficking data sheet: Myanmar [Internet]. Office of United Nations Resident Coordinator in Myanma; 2009. Available from: http://www.no-trafficking.org/reports_docs/myanmar/myanmar_siren_ds_march09.pdf.

- Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development, UNICEF. Situation analysis of children in Myanmar [Internet]. Myanmar, Nay Pyi Taw; 2012. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/eapro/Myanmar_Situation_Analysis.pdf.

- Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women. Myanmar/Burma Breaking Barriers: Advocating sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://arrow.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Myanmar-Burma-Country-Study.pdf.

- Tanabe M, Robinson K, Lee CI, et al. Piloting community-based medical care for survivors of sexual assault in conflict-affected Karen State of eastern Burma. Confl Health. 2013;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-12

- Women’s League of Burma. CEDAW shadow report: Burma 2008 [Internet]. Chiang Mai, Thailand; 2008. Available from: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cedaw/docs/ngos/Women_Burma42.pdf.

- The Gender Equality Network. Behind the silence: violence against women and their resilience, Myanmar [Internet]. Yangon, Myanmar; 2015. Available from: http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs21/GEN-2015-02-Behind_the_Silence-en-red.pdf.

- Falb KL, McCormick MC, Hemenway D, et al. Symptoms associated with pregnancy complications along the Thai-Burma border: The role of conflict violence and intimate partner violence. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:29–37. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1230-0

- Schlecht J. A girl no more: the changing norms of child marriage in conflict [Internet]. Women’s Refugee Commission; 2016 [cited 2016 Jul 13]. Report No.: ISBN:1-58030-153-3. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/girls/resources/1311-girl-no-more.

- Dedoose [Internet]. [cited 2016 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.dedoose.com/.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Fact-finding mission on Myanmar: concrete and overwhelming information points to international crimes. 2018 Mar 12 [cited 2018 Oct 11]; Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/Pages/NewsDetail.aspx?NewsID=22794&LangID=E.

- Human Rights Watch. “All of My Body Was Pain”: sexual violence against Rohingya Women and Girls in Burma [Internet]. Human Rights Watch; 2017 [cited 2018 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/11/16/all-my-body-was-pain/sexual-violence-against-rohingya-women-and-girls-burma.

- Karen Human Rights Group. Attacks on villagers, ongoing fighting and displacement in Hpapun and Toungoo districts from January to April 2018 [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://khrg.org/sites/default/files/18-1-nb1_wb.pdf.

- Karen Human Rights Group. Hidden strenghts, hidden struggles: women’s testimonies from southeast Myanmar [Internet]. 2016. Report No.: 2016–01. Available from: http://khrg.org/sites/default/files/khrg_july_2016_hidden_strengths_hidden_struggles_english_resize.pdf.

- Parmar PK, Barina C, Low S, et al. Migration patterns & their associations with health and human rights in eastern Myanmar after political transition: results of a population-based survey using multistaged household cluster sampling. Confl Health. 2019;13(15).

- Parmar PK, Barina CC, Low S, et al. Health and human rights in eastern Myanmar after the political transition: a population-based assessment using multistaged household cluster sampling. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0121212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121212

- Foster AM, Arnott G, Hobstetter M, et al. Establishing a referral system for safe and legal abortion care: a pilot project on the Thailand-Burma border. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;42:151–156. doi: 10.1363/42e1516

- Asnong C, Fellmeth G, Plugge E, et al. Adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of pregnancy in refugee and migrant communities on the Thailand-Myanmar border: a qualitative study. ReprodHealth. 2018;15:83.

- Kågesten AE, Zimmerman L, Robinson C, et al. Transitions into puberty and access to sexual and reproductive health information in two humanitarian settings: a cross-sectional survey of very young adolescents from Somalia and Myanmar. Confl Health. 2017;11(24).

- UNHCR. 2019 joint response plan for the Rohingya refugee crisis [Internet]. Geneva; 2019; [cited 2019 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh/document/2019-joint-response-plan-rohingya-humanitarian-crisis-january.

- Chynoweth S. “It’s Happening to Our Men as Well”: sexual violence against Rohingya men and boys [Internet]. Women’s Refugee Commission; 2018. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/gbv/resources/1664-its-happening-to-our-men-as-well.

- Gatuguta A, Katusiime B, Seeley J, et al. Should community health workers offer support healthcare services to survivors of sexual violence? A systematic review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2017;17(28).

- Karen Human Rights Group. Village Agency: Rural rights and resistance in a militarized Karen State [Internet]. 2008. Report No.: KHRG#2008-03. Available from: http://khrg.org/sites/default/files/khrg0803.pdf.