Abstract

Complications from abortion, while rare, are to be expected, as with any medical procedure. While the vast majority of serious abortion complications occur in parts of the world where abortion is legally restricted, legal access to abortion is not a guarantee of safety, particularly in regions where abortion is highly stigmatised. Women who seek abortion and caregivers who help them are universally negatively “marked” by their association with abortion. While attention to abortion stigma as a sociological phenomenon is growing, the clinical implications of abortion stigma – particularly its impact on abortion complications – have received less consideration. Here, we explore the intersections of abortion stigma and clinical complications, in three regions of the world with different legal climates. Using narratives shared by abortion caregivers, we conducted thematic analysis to explore the ways in which stigma contributes, both directly and indirectly, to abortion complications, makes them more difficult to treat, and impacts the ways in which they are resolved. In each narrative, stigma played a key role in the origin, management and outcome of the complication. We present a conceptual framework for understanding the many ways in which stigma contributes to complications, and the ways in which stigma and complications reinforce one another. We present a range of strategies to manage stigma which may prove effective in reducing abortion complications.

Résumé

Si l’avortement s’accompagne rarement de complications, elles sont néanmoins possibles, comme avec tout acte médical. Alors que la grande majorité des complications graves de l’avortement surviennent dans des régions du monde où cette pratique est limitée par la loi, l’accès légal à l’avortement n’est pas une garantie de sécurité, en particulier là où l’avortement est fortement stigmatisé. Les femmes qui souhaitent avorter et les soignants qui les aident sont universellement “marqués” négativement par leur association avec l’avortement. La stigmatisation de l’avortement comme phénomène sociologique fait l’objet d’une attention grandissante, mais ses conséquences cliniques, en particulier son impact sur les complications de l’avortement, ont reçu moins de considération. Nous explorons ici les intersections de la stigmatisation de l’avortement et des complications cliniques, dans trois régions du monde avec différents climats juridiques. En nous servant des récits des soignants en cas d’avortement, nous avons mené une analyse thématique pour examiner comment la stigmatisation contribue, directement et indirectement, aux complications de l’avortement, les rend plus difficiles à traiter et influence la façon dont elles sont résolues. Dans chaque récit, la stigmatisation a joué un rôle clé dans l’origine, la prise en charge et l’issue de la complication. Nous présentons un cadre conceptuel pour comprendre les nombreuses manières dont la stigmatisation contribue aux complications et comment la stigmatisation et les complications se renforcent mutuellement. Nous décrivons une gamme de stratégies pour gérer la stigmatisation qui peuvent se révéler efficaces pour réduire les complications de l’avortement.

Resumen

Las complicaciones del aborto, aunque raras, son de esperarse, al igual que con cualquier otro procedimiento médico. Aunque la gran mayoría de las complicaciones graves del aborto ocurren en partes del mundo donde el aborto es restringido por la ley, el acceso legal a los servicios de aborto no es garantía de seguridad, en particular en regiones donde el aborto es sumamente estigmatizado. Las mujeres que buscan un aborto y los prestadores de servicios que las ayudan son “marcados” universalmente de manera negativa por su asociación con el aborto. Aunque la atención al estigma del aborto como fenómeno sociológico está en alza, las implicaciones clínicas del estigma del aborto, en particular su impacto en las complicaciones del aborto, han recibido menos consideración. Aquí exploramos la intersección del estigma del aborto y las complicaciones clínicas, en tres regiones del mundo con diferentes contextos legislativos. Utilizando narrativas compartidas por prestadores de servicios de aborto, realizamos análisis temático para explorar las maneras en que el estigma contribuye, directa e indirectamente, a las complicaciones del aborto, dificulta su tratamiento y afecta las maneras en que se resuelven. En cada narrativa, el estigma desempeñó un papel clave en el origen, manejo y resultado de la complicación. Presentamos un marco conceptual para entender las numerosas maneras en que el estigma contribuye a las complicaciones y las maneras en que el estigma y las complicaciones se refuerzan mutuamente. Presentamos una variedad de estrategias para manejar el estigma, las cuales podrían resultar eficaces para disminuir las complicaciones del aborto.

Introduction and theoretical framework

Five million women are hospitalised worldwide each year for abortion-related complications.Citation1 Complications range from those that are minor and can be easily treated to those that, while rare, are serious and can result in morbidity or even death. While the vast majority of serious complications occur in regions of the world where abortion is legally restricted,Citation2 the relationship between the legal status of abortion and abortion safety is nuanced. Both highly trained and ill-trained providers work in both legally permissive and legally restrictive climates. Women in both settings may self-manage their abortions, some using safe techniques, and some with harmful tactics. In other words, legal access to abortion cannot be equated with a guarantee of safety, particularly in areas where abortion is highly stigmatised – a phenomenon that cuts across legal settings.Citation3 While restrictions on abortion vary by region and country, abortion stigma is a nearly global phenomenon. Here we consider the intersection of abortion stigma with abortion complications, both in regions of the world where abortion is highly restricted and without significant restriction.

Erving Goffman first defined stigma as an attribute that is “deeply discrediting”, which moves someone from being seen as “whole and usual person, to a tainted, discounted one”.Citation4 Stigma related to abortion is prominent across the globe. Abortion stigma impacts individuals and organisations associated with the procedure, including women who have abortions, those to whom they are connected (partners, family members and friends), abortion advocates, researchers, and clinicians who provide care. These groups are all negatively “marked” by their association with abortion.Citation5

Experiences with abortion stigma, for both women seeking the procedure and their caregivers, fall into three general domains: perceived stigma, enacted stigma and internalised stigma.Citation6–9 Perceived stigma, or one's feelings about how others do or may react once an abortion experience is revealed, perhaps most commonly leads to silence and censorship, in anticipation of judgment, rejection and loss of relationships.Citation8,Citation10–12 Prior research in the US has shown that women are more likely to disclose experiences with miscarriage than abortion, which carries less social judgment and stigmatisation,Citation13 and can resort to concealment, creating cover stories and lying to avoid disclosing their abortions to others.Citation14 This secrecy and silence results in the shared idea that abortion is uncommon and abnormal, perpetuating a social norm that abortion is deviant, and thus generating further silence around abortion decisions.Citation10 Enacted, or experienced, stigma is the actual experience of negative treatment or discrimination as a result of one's abortion experience being known. This may mean rejection, mistreatment, discrimination, abuse and devaluation for both patients seeking abortion and their caregivers.Citation8 Additionally, health care workers may experience marginalisation within medical communities, harassment or violence.Citation12 Finally, internalised stigma, or one's own beliefs about their experience or involvement or experience with abortion, can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, embarrassment and self-blame.Citation9

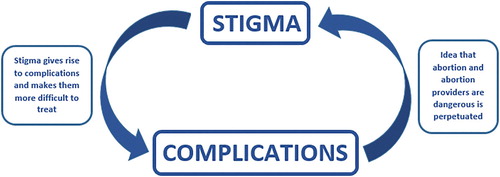

Here we explore the possible relationships between stigma and abortion complications, considering stigma experienced by patients and healthcare providers. While scholars, advocates and care providers all widely agree that abortion stigma is pervasive, few have described its impact on abortion complications. Stigma generates and reinforces many stereotypes of those who seek the procedure and those who provide the care. Kumar and colleagues described a vicious cycle of stigma and silence termed the “prevalence paradox”, in which people who have abortions do not report on their experiences, leading to an understanding of abortion as uncommon and perpetuating a social norm that it is deviant.Citation10 This then leads to discrimination against those who have abortions, further perpetuating fear around disclosure of abortion, and the cycle continues. This cycle of stigma and silence was later applied to caregivers, described as the “legitimacy paradox”.Citation15 Many abortion caregivers do not routinely disclose their work in everyday situations, perpetuating a stereotype that abortion work is deviant and illegitimate. This stereotype leads to the marginalisation of abortion work within medicine, and harassment and violence against abortion caregivers. These outcomes lead to further reluctance to disclose abortion work, continuing the cycle of stigma and silence. Here we suggest that stigma and abortion complications also exist together in another vicious cycle (). Complications in abortion care contribute to the idea that abortion is dangerous and negatively impacts women's health, and that abortion providers are unskilled and technically deficient. The notion that abortion, and the physicians who offer the procedure, are dangerous further generates more stigma, and often leads to the justification of further legal restrictions for abortion, thus contributing to more complications and worse outcomes for women. The cycle then continues. We present three stories below that demonstrate this relationship, and describe how abortion stigma, directly and indirectly, can lead to complications, make them more difficult to treat, and impact the ways in which those affected – both patients and caregivers – process the ways in which they resolve.

Stories shared are from three continents: North America, South America and Africa, regions of the world where the legal status of abortion varies, but its stigmatisation is common to all. It is often difficult to isolate the impact of stigma from restrictive abortion law, especially in the setting of abortion complications. For example, in settings where abortion is restricted or has an ambiguous legal status, hesitation to disclose an abortion by a patient or provider (as seen in the cases below) may be a result of the “mark” of stigma, but may also stem from fear of legal consequences. Other healthcare workers’ unwillingness to assist a patient may be rooted in stigmatising attitudes, but may also represent fear of legal ramifications. The intersecting effects of stigma and legal restriction are reflected in the stories shared here.

Methods

The stories presented here were shared by healthcare providers who offer abortion or treatment for self-managed or otherwise unsafe abortions, often referred to as post-abortion care, as part of their participation in the Providers Share Workshop (PSW). PSW is a facilitated group intervention that provides abortion caregivers an opportunity to reflect on their work experiences, including the burden of abortion stigma. Workshops are structured around five session themes, which follow an intentional emotional arc, allowing for safety, sharing and openness within the group. Workshops employ narrative story-telling and reflection, as well as arts-based methodologies including collage and photography, to help participants engage with topics and experiences that may be intensely emotional. Full workshop methods have been described in detail elsewhere.Citation12,Citation16

Our team conducted a pilot workshop at one US abortion clinic in 2007.Citation12 We subsequently implemented the PSW at eight US abortion clinics from 2010–2012.Citation17 In 2014, we adapted the workshop content and pilot-tested it with participants working in Latin America and Africa. Here we reflect on the narratives shared by participants in these three PSW iterations. In all cases, workshop sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The University of Michigan's Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved all three studies. Study protocols for the international pilot project were also reviewed by two independent IRB's. Participants provided either written or oral consent to participate in the study and to be audio-recorded.

Data Analysis

Workshop audio recordings were transcribed and translated from Spanish and a local African language to English as needed. Transcripts did not include identifying information about participants or their organisations. Narratives reflected in this manuscript were shared in sessions titled “Memorable patients” (US) and “Difficult cases and memorable complications” (international). Study team members read each of the transcripts independently. We later collaboratively identified major themes and established an initial coding scheme. Transcripts were independently coded in three rounds using an iterative coding process until all transcripts were coded by all three team members. Coding disagreements were resolved through consensus. Data collected from the initial US pilot transcripts were coded using NVivo 8.Citation18 The transcripts from the second, multi-site US study and the international study were coded with the assistance of Dedoose.Citation19 After our initial analysis of all workshop data, the three stories shared below were selected by members of the study team in collaboration with our global partners. We examined these stories specifically using thematic analysis, identifying larger themes, underlying social factors and processes at play that emerged. The theme “stigma” was evident in each narrative; several sub-themes such as “stigmatisation of women”, “stigma within medical institutions”, “medical marginalisation”, “impacts of legal restriction” and “community condemnation” were also present.

The stories below moved PSW participants tremendously. Their power came, in some cases, from their tragic endings, and in others from the determination with which care providers overcame a wide range of barriers and obstacles to safe patient care. What they all shared was the centrality of the role of abortion stigma – the stigmatisation of both women seeking abortion and the caregivers who help them – in the origin, treatment or outcome of the complication. In two out of three cases, the impacts of stigma are further amplified by the legally restrictive context for the work.

Results

Case one

(In this African country, abortion was legally permitted in limited circumstances, such as to preserve a woman's life or health. Post-abortion care, if a woman's life or health is at risk, was legally permissible.)

A nurse shared a story of a client who presented to a family planning clinic complaining of abdominal pain. The patient reported that she was not pregnant and was seeking pain relief for menstrual cramps. While she was waiting to be seen, the physician gave her some pain medication and told her to rest on the couch while the medication took effect. After about 30 min, the patient approached the front desk clerk reporting, “The pain is too much, please help me”. Clinic staff again asked the woman if she might be pregnant. She said no; she was just having menstrual cramps. After a while, the woman began to cry; “the pain is too much”, she said. She declined a physical exam, or any urine or blood testing. Suddenly, she started bleeding heavily and passing large blood clots. The centre manager rushed her to an exam room. Still, she would not permit a pregnancy test to be done and denied repeatedly that she was pregnant. The patient also expressed that her husband did not know she was at the health centre, and the staff should not inform him of her visit; however, the woman did not have any money or transportation and her husband needed to come to pay her bill and take her home. The staff called her husband and, at the patient's request, invented a story about why she was there. By the time her husband arrived, her pain had decreased and she went home without determining a clear reason for her pain. The staff were still unable to confirm whether or not the woman was or had been pregnant.

The woman and her husband came back the next day. The woman's skin and eyes were completely yellow. The staff administered a hepatitis test; it was negative. The patient gave a stool sample, which was black. The physician thought she must have typhoid, and decided to refer her to a hospital. There was some debate about where to send her, however. Clinic staff feared that because they were known as providers of safe post-abortion and family planning care, they would be accused of performing an illegal abortion, and causing her grave complication. The nurse shared,

“If the people [we refer her to] knew that it was from [our clinic], they will start saying that we did an abortion on her and the complications are from that; we are not to give them the problem [of treating this woman's complication].”

A few days following the woman's passing, the fears of the clinic staff that they would be blamed for performing an abortion came true. The nurse sharing the story was acquainted with the woman's brother and her husband through her church. The nurse reflected,

“Her brother goes to the same church as me. He [confronted] me in the street. I was walking with a friend and he yelled to me: ‘You knew my sister. You are the one who killed my sister and I am going to the police to report it; you guys will be in trouble’. The husband [of the patient] was joining this man, because he found out his wife was doing an abortion, and he said that the abortion was done at [our clinic]. They were [verbally] attacking me.”

Case two

(In this Latin American country, at the time this story took place, abortion was illegal with no exceptions.)

Although this particular incident happened many years earlier, it was so memorable that one obstetrician-gynaecologist (ob-gyn) felt compelled to share it when the topic of abortion complications arose. The story began when he received a request from a close colleague – a paediatric surgeon – who had a patient who was experiencing complications following an abortion procedure the surgeon had performed. The ob-gyn went to see the colleague; when he arrived the patient was on a gurney, stable with IV fluids. At that time, abortions were performed using dilation and curettage, not suction, and sometimes used tweezers. The paediatric surgeon explained the patient's cervix had been dilated and he was extracting the uterine contents when suddenly he encountered resistance as he pulled. The ob-gyn relaying the story began to imagine the worst, that his colleague may have perforated the patient's uterus, and perhaps damaged her intestine. His colleague administered antibiotics and IV fluids, knowing that the woman would need a laparotomy (a surgical incision in the abdomen); “that would be a bigger problem for him and for her”, as he put it. The two men looked for a “friendly” clinic. They contacted an anaesthesiologist colleague; the owner of that clinic did not want to help them. The ob-gyn shared, “We spent the whole day looking for clinics and none of them would let us operate there, [out of] fear. The mistake we made was to tell the truth.” After six hours, there had been no change in the patient's status. The next day, the ob-gyn sharing the story returned to his own practice. More than 12 hours had passed and the patient was still stable. The ob-gyn contacted another hospital and arranged for the patient to be admitted with a different type of complication, unrelated to abortion, so she would not be turned away. The surgeon continued to monitor her at his clinic and after further evaluation and testing, determined that while there had likely been a uterine perforation, there had been no intestinal injury, or damage to other nearby organs. The two doctors concluded that the defect in the uterus appeared to be healing. The ob/gyn reflected on the experience, “It was very traumatic for me, and because he was very close to me, I got involved. For him that was the end of it because he never did that type of procedure again.”

Case three

(In this North American region, abortion was legal but a number of restrictions made it difficult to access.)

A physician working at a university hospital family planning department received a referral for the care of a patient of approximately 12 gestational weeks, who had been turned away by several outpatient abortion clinics. She had large uterine fibroids (benign muscle growths) that prevented access to the pregnancy. The pregnancy was located in the upper portion of the uterus, corresponding to the right quadrant of her abdomen, and could not be reached from the cervix. She also had a range of mental health issues, including agoraphobia and an anxiety disorder. The physician at the hospital explored several different options for her care, ultimately deciding to perform a small laparotomy (defined earlier), making an incision in the top of the uterus and using suction to remove the pregnancy. She explained,

“We came up with [a plan], and I guess I still would do it the same way, but it was definitely not … the way you really want to go. Ideally you try to do everything without doing an incision on the belly. But it just seemed like it was not going to be possible [any other way] and we’d had some other experiences in the past that made me feel like [that was] the best thing for her to do. I went over this with everybody I knew and I think most people were on my side but there [was] definitely controversy and, you know, everybody had some concerns.”

“I mean there was no doubt that this was risky to her, but the pregnancy was risky as well. She was also Catholic and she had some discomfort with the idea of having an abortion, but I think in the end I felt pretty comfortable that we had come to the best [solution].”

“The thing that I just started thinking about is, why do I do this? I had this vision of, this lady dies, my name's going to be in the paper, or my kid's life is going to be ruined, about something that I think in the end wasn’t a bad decision, but taking it out of context, it was going to be terrible.”

“I had to re-present this case about a half dozen times to the department. I felt like it was [handled] pretty well but, you just always feel a little bit like there are certain people that are like, “that is what you get [for doing abortions]”. I [also] had this scenario going through my mind that it was going to ruin my kid's life … If I had something like that happen … I would never get a job anywhere else. So I started thinking about, why do I do this?”

Analysis

These stories show a range of relationships between abortion stigma and complications. While there were undoubtedly clinical and legal factors at play in all three cases, they also all highlight manifestations of stigma which significantly contributed to serious complications. Stigma can, directly and indirectly, contribute to the onset of complications, make complications more difficult to treat, and the complications can, in turn, manifest more stigma.

In the first case, the patient would not disclose to her partner, family or clinic staff that she had ended her pregnancy, until it was too late. Non-disclosure of a stigmatised attribute or behaviour is a well-described feature of stigma – particularly if the stigmatised attribute is invisible, meaning that others would not know about it if it were not disclosed.Citation10 By denying she was pregnant and refusing to take a pregnancy test, her caregivers were left without crucial information that could have allowed them to treat her sooner and perhaps save her life. As post-abortion care was legal in this country, there would have been legal options to treat her, if the staff had known about her self-managed abortion. Her caregivers were also hesitant to transfer her to another care setting, for fear of being accused of providing her with an abortion, and anticipated that other care settings would be unwilling to assist the patient and expect them to treat her themselves, which they were unable to do. Given that there were not legal barriers to treating her given the circumstances, any hesitation to get involved in the woman's care would have been rooted in stigma, and the desire not to be associated with abortion. Her caregivers were left to rely on established relationships with other clinics who were known to be helpful and supportive, instead of referring the woman directly to a hospital, inevitably causing a delay. For the nurse sharing the story, the fear of being blamed for procuring an abortion became true when the woman’s brother and husband publicly confronted her in front of their church community, accusing her of causing the woman's death, and threatening to go to the police. Had the patient died from another, less socially contested cause, such as tetanus or malaria, a confrontation of this nature likely would not have occurred. This encounter also served as a public “outing” of the story-teller as someone involved in abortion care. While the reactions from others in this church community around this confrontation were not shared, this fear of community condemnation is common for many providers, and is, in part, what motivates many to stay silent about their work.Citation12

Case Two also demonstrates the challenges faced when referring a patient for treatment at another facility following a complication. Here, the participant admitted that both he and the provider avoided transferring the patient to a hospital, for fear of negative consequences for both providers and the patient. As both abortion and post-abortion care was not legally allowed under any circumstances, the story-teller here was likely referring to legal consequences for the patient and her caregivers. But there would have been social consequences as well. As in the first case, complications can serve as an “outing” for both patients and their caregivers, revealing their experience with abortion to others, when they may have preferred otherwise to remain silent. This can lead to judgment, rejection, embarrassment, and loss of relationships.Citation12 Both doctors were driving all night, looking for a clinic that would admit them. As in Case One, both physicians tried to rely on established relationships with other physicians who were known to be supportive of abortion, but even then were unsuccessful. After facing rejection from multiple clinics as they attempted to admit the patient as a post-abortion complication, the story-teller settled on a stigma management tactic in order to get the patient the care that she needed. He shared that it was easier to conceal that their patient had an abortion, and admit the case as a different type of complication. Once the story-teller made arrangements for the patient to be admitted as a complication unrelated to abortion, he encountered no difficulty or pushback. The decision to conceal an abortion brings about its own stress however, as the caregivers must be sure that the abortion will not be revealed, which can involve changing paperwork and medical records, lying to patient's family members, and ensuring the patient themselves will not disclose their abortion. While the patient here ultimately recovered, there were serious lapses in her care and delays in treatment. This story had a lasting influence on the story-teller, who broke down into tears during the workshop, recounting it from many years earlier. For the original paediatric surgeon, the stress and trauma of managing the case was enough for him to stop offering abortion care altogether. This represents another impact of stigma, as many caregivers experience complications from abortion as different, and more difficult, than complications encountered in other medical care.Citation12

The resolution of complications, and the impact on the provider's well-being, was central in Case Three. The physician feared that this case would result in condemnation in her broader community, similar to Case One. She feared that if the patient in her care died, the case would inevitably make it into the media and be taken out of context, impacting her ability to get a job at another institution and impacting her child’s life and well-being. The stress of the situation, amplified by the stigmatised nature of abortion, led her to immediately imagine these conclusions before the case had even been resolved. As mentioned earlier, stigma impacts the way that providers interpret and react to complications and the ways they are resolved, making them feel more challenging than other types of complications. This case led the physician to question her own judgment, be on the receiving end of questions and doubt from colleagues, and impacted her sense of her standing within medicine. Even though she stood by her decision and was backed by many of her supportive colleagues, she still felt the need to defend her decisions to her department many times. She felt a lack of sympathy and understanding from some, and sensed they may feel that any sort of complication was deserved, as a punishment for doing abortions. Whether or not her feelings reflect her colleagues’ actual beliefs, or her own internalised stigma, is unclear – but either is a reflection of the widespread stigmatisation and marginalisation of abortion from the rest of the medical community, which is acutely apparent in the setting of a complication. The stigmatisation of abortion leads to feeling as if there is no room for error, and, similar to Case Two, caused this physician to question leaving her abortion work and medicine altogether. The impacts of abortion complications can have serious human resource implications for the abortion-providing workforce. If the pressure and trauma associated with abortion complications can cause caregivers to want ultimately to leave their work, there may be difficulty in sustaining a thriving workforce of trained, skilled clinicians in the future.

Discussion

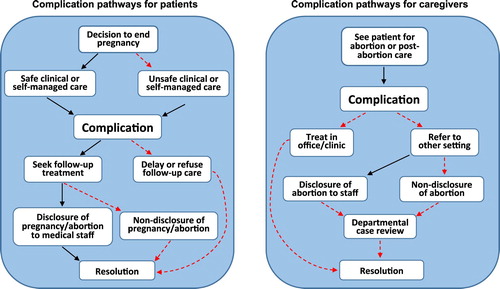

We present a conceptual model of pathways to abortion complications in , for both patients and providers. Arrows in red represent points along the pathway where stigma can have an impact, as evidenced in the stories shared above. For patients, stigma impacts their decisions about how and where to seek care, whether or not to seek follow-up care following a complication and whether to disclose their pregnancy and abortion to their medical staff. For providers, stigma impacts their decisions about whether to refer patients when there is a complication or attempt to treat in-office, whether or not to disclose the pregnancy and abortion when making a referral, their treatment in case reviews, and their eventual resolution.

Figure 2. Pathways to abortion complications

Note: Dotted arrows represent points along the pathway where stigma can have an impact, as evidenced in the stories above.

There are also many points where stigma may have impacts on abortion complications, for both clinicians and patients, that are not represented by these stories, but were shared by other participants in the PSW. Both clinicians and patients can start to internalise and believe prominent negative stereotypes in the setting of a complication: patients can start to believe that they are bad people; clinicians may start to think of themselves as “hacks” or “butchers”. Many patients blame themselves for complications, feeling as though they are deserved as a form of punishment for seeking an abortion. In settings where abortion is legally restricted, doctors have faced threats of extortion by the police following a complication. Additionally, working in a clinic with a known reputation as a “safe” abortion provider, or provider of post-abortion care, brings a certain amount of pressure, as if there is no room for error. Concerned with maintaining clinic reputations, administrations may denigrate staff when complications do inevitably occur. Complications may also provide fodder for anti-abortion activists, particularly if the patient is transported to an emergency setting. In the US, anti-abortion protestors have filmed patients being transported to another setting for emergency care, or may listen in to 911 calls, hoping to discover calls for assistance following a complication, with the aim of making the calls public in order to shame patients and clinicians.Citation20 Additionally, in the US, public insurance does not typically cover abortion in 34 states except in rare circumstances,Citation21 a clear product of stigma, singling out abortion as ineligible for funding. Given funding issues, caregivers may feel pressured to care for women in less costly outpatient clinic settings, even if underlying health issues would make hospital-based care a safer option. These factors beg us to question the extent to which providers’ decisions around if and when to transport patients to another setting following a complication are influenced by stigma.

Dismantling the many manifestations of abortion stigma, particularly as they intersect with patient care and safety, is a significant public health issue. As discussed above, the impacts of stigma and legal restriction are often overlapping and reinforce one another. Thus, efforts to reduce unsafe abortion and maternal mortality should not focus solely on reducing legal restrictions, but rather broader de-stigmatisation and culture change at the individual, community and institutional levels, as liberalisation of abortion laws alone is likely not enough to protect women's health. Significant cultural change around abortion is needed around the world in order to reduce stigma, improve restrictive legal climates, and shift polarised discourse around abortion. Short of such changes, many women will continue to feel unable to openly discuss their pregnancy options with their partners, family members, friends and care providers, and concealment and secrecy around abortion will likely still persist.

While there are many organisations aiming to reduce abortion stigma, underlying cultural change around abortion is a long-term process that will not happen quickly. In the short term, strategies to manage stigma may have positive impacts on patients’ safety and well-being. Recently, new initiatives have aimed to improve the safety of self-managed abortion, especially for women who do not have access to safe abortion providers.Citation22 Supportive interventions and workshops may contribute to improving abortion attitudes among staff members who are not directly involved in abortion care, and there is likely a role for programmes such as the PSW and Values Clarification exercises in addressing stigma amongst medical staff to ease hospital referrals and ultimately improve patient safety.Citation23 In separate work, our research team has established a cohort of supportive subspecialists from a range of medical backgrounds who family planning specialists can contact directly for consultation when seeing medically complicated patients. Participants have shared that the programme allowed many patients to be seen in outpatient, rather than hospital settings, reducing delays and added costs for patients.Citation24 Many have also shared that they feel more integrated into the broader medical community and less isolated, a well-documented effect of stigma.Citation12 Similar models may be helpful for streamlining referral and consultation processes in other settings, which may positively impact patient safety.

Through these cases it is evident that stigma matters, beyond just its usefulness as a descriptive sociological concept, and has real consequences for women and their care providers. These cases beg us to question how many serious complications and deaths of women can be directly attributed to stigma, and may not have otherwise occurred if women felt comfortable discussing their abortion decisions openly with their partners, families and care providers. They raise the question around lapses of care that may been avoided if abortion providers had equal standing within medicine, were respected by their medical colleagues, and cases were treated with urgency, compassion and empathy. While there have been recent efforts to reduce abortion stigma, many have focused on the personal benefits of sharing abortion stories, and mobilising abortion experiences for legislative change. Few efforts have focused on the clinical implications of broader de-stigmatisation, although these findings indicate that this should be imperative. Abortion stigma is a global public health and maternal mortality issue, one which must be addressed urgently by those working to improve women's health around the globe.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Haddad L, Nour N. Unsafe abortion: unnecessary maternal mortality. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Spring;2(2):122–126.

- Grimes D, Benson J, Singh S, et al. Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic. The Lancet. 2006 Nov;368(9550):1908–1919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6

- Barot S. The roadmap to safe abortion worldwide: lessons from new global trends on incidence. Leg Saf. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2018;21:17–22.

- Stigma: GE. Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York (NY): Simon & Schuster, Inc.; 1963; p.3.

- Norris A, Bessett D, Steinberg J, et al. Abortion stigma: a reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Women’s Health Issues. 2011 Feb;21(3):S49–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.010

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav. 1997 Jun;38(2):177–190. doi: 10.2307/2955424

- Fife BL, Wright ER. The dimensionality of stigma: a comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J Health Soc Behav. 2000 Mar;41(1):50–67. doi: 10.2307/2676360

- Shellenberg K, Moore A, Bankole A, et al. Social stigma and disclosure about induced abortion: results from an exploratory study. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(1):S111–S125. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.594072

- Hanschmidt F, Linde K, Hilbert A, et al. Abortion stigma: a systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016 Dec;48(4):169–177. doi: 10.1363/48e8516

- Kumar A, Hessini L, Mitchell E. Conceptualising abortion stigma. Cult Health Sex. 2009 Aug;11(6):625–639. doi: 10.1080/13691050902842741

- Major B, Gramzow R. Abortion as stigma: cognitive and emotional implications of concealment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(4):735–745. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.735

- Harris L, Martin L, Hassinger J, et al. Dynamics of stigma in abortion work: findings from a pilot study of the providers share workshop. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(7):1062–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.004

- Cowan SK. Secrets and misperceptions: the creation of self-fulfilling illusions. Sociol Sci. 2014 Nov;1:466–492. doi: 10.15195/v1.a26

- Cockrill K, Nack A. “I’m not that type of person”: managing the stigma of having an abortion. Deviant Behav. 2013;34:973–990. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2013.800423

- Harris L, Martin L, Hassinger J, et al. Physicians, abortion provision and the legitimacy paradox. Contraception. 2013;87:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.031

- Debbink M, Hassinger J, Martin LA, et al. Experiences with the providers share workshop method: abortion worker support and research in Tandem. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1823–1827. doi: 10.1177/1049732316661166

- Martin L, Hassinger J, Seewald M, et al. Evaluation of abortion stigma in the workforce: development of the revised abortion providers stigma scale. Womens Health Issues. 2018 Jan;28(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.10.004

- NVivo qualitative data analysis software. QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 8, 2008.

- Dedoose Version 5.0.11 web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles (CA): SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2014.

- Ornstein C. Activists pursue private abortion details using public records laws. ProPublica [Internet]. 2015 Aug 25; Available from: https://www.propublica.org/article/activists-pursue-private-abortion-details-using-public-records-laws.

- State Funding of Abortion under Medicaid [Internet]. (2019). Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/state-funding-abortion-under-medicaid.

- Women Help Women [Internet]. Available from: https://womenhelp.org/

- Turner KL, Page KC. (2008). Abortion attitude transformation: A values clarification toolkit for global audiences. Chapel Hill, NC, Ipas. Available from: https://ipas.azureedge.net/files/VALCLARE14-VCATAbortionAttitudeTransformation.pdf.

- Personal communication with program participants, 2019.