Abstract

In the context of a growing adolescent population globally, it is imperative to understand which interventions will most effectively advance their sexual and reproductive health (SRH). In India and globally, peer education is often utilised as an intervention for promoting the SRH of young people. Globally, the evidence of its effectiveness is mixed. A systematic review of the literature from the Indian context gave insight into the knowledge, attitudinal, and behavioural (KAB) outcomes affected by peer education, as well as the inputs, coverage, content, and context of such interventions. Out of the over 1500 publications initially identified through the database and bibliographic searches, 13 were included in the review; no quality assessment was done, given the dearth of publications matching the inclusion criteria. Analysis of the included publications highlights the multiple ways that peer education is implemented in the Indian context, as part of multi-component programmes and as a stand-alone intervention. The KAB outcomes from these initiatives are mixed, with some multi-component and some stand-alone initiatives affecting statistically significant outcomes and others not–a finding consistent with global literature reviewed for this paper. Despite the mixed results and the limited effects of behaviour relative to knowledge, this paper proposes that peer education has a place in an overall response to improving the SRH of young people. It calls for better research on peer education in India, and for research in relation to the optimal conditions for peer education to succeed in affecting KAB and other outcomes.

Résumé

Avec une population adolescente croissante dans le monde, il est impératif de comprendre quelles interventions feront le plus efficacement progresser la santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR) de ce groupe. En Inde et dans le monde, l’éducation par les pairs est souvent utilisée comme une intervention pour promouvoir la SSR des jeunes. Dans le monde, les données sur son efficacité ne sont guère concluantes. Un examen systématique des publications issues du contexte indien a donné un éclairage sur les connaissances, les attitudes et les pratiques (CAP) influencées par l’éducation par les pairs, ainsi que les contributions, la couverture, le contenu et le contexte de ces interventions. Sur les plus de 1500 publications initialement identifiées par des recherches bibliographiques et dans la base de données, 13 ont été incluses dans l’examen; aucune évaluation de la qualité n’a été faite, compte tenu de la rareté des publications réunissant les critères d’inclusion. L’analyse des publications incluses souligne les manières multiples dont l’éducation par les pairs est mise en œuvre dans le contexte indien, dans le cadre de programmes à multiples composantes ou comme intervention autonome. Les résultats de ces initiatives en matière de CAP sont disparates, certaines initiatives autonomes ou à multiples composantes obtenant des résultats statistiquement significatifs alors que d’autres non, une observation qui cadre avec les publications mondiales examinées pour cet article. En dépit des résultats nuancés et des effets limités des pratiques relatives aux connaissances, l’article suggère que l’éducation par les pairs a sa place dans une réponse globale pour améliorer la SSR des jeunes. Il demande des recherches de meilleure qualité sur l’éducation par les pairs en Inde et des recherches en rapport avec les conditions optimales pour que l’éducation par les pairs parvienne à influer sur les CAP et d’autres résultats.

Resumen

En el contexto de la creciente población de adolescentes a nivel mundial, es imperativo entender qué intervenciones promoverán su salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) de la manera más eficaz. En India y en el resto del mundo, la educación de pares a menudo se utiliza como intervención para promover la SSR de jóvenes. Mundialmente, la evidencia de su eficacia es mixta. Una revisión sistemática de la literatura del contexto indio permitió ver los resultados relacionados con los conocimientos, actitudes y comportamientos (KAB, por sus siglas en inglés) afectados por la educación de pares, así como los aportes, cobertura, contenido y contexto de las intervenciones. De más de 1500 publicaciones identificadas inicialmente por medio de búsquedas en bases de datos y en bibliografías, trece fueron incluidas en la revisión; no se realizó una evaluación de la calidad, debido a la escasez de publicaciones que reúnen los criterios de inclusión. El análisis de las publicaciones incluidas destaca las diversas maneras en que la educación de pares es aplicada en el contexto indio, como parte de programas de múltiples componentes y como intervención independiente. Los resultados KAB de estas iniciativas son mixtos, ya que algunas iniciativas con múltiples componentes y otras independientes producen resultados estadísticamente significativos mientras que otras no. Este hallazgo concuerda con la literatura mundial revisada para este artículo. A pesar de resultados mixtos, y de los efectos limitados del comportamiento con relación al conocimiento, este artículo propone que la educación de pares tiene lugar en la respuesta general para mejorar la SSR de las personas jóvenes. Insta a realizar mejores investigaciones sobre la educación de pares en India, y a velar por que las investigaciones relacionadas con las condiciones óptimas para la educación de pares logren afectar KAB y otros resultados.

Introduction

Young people’s sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is recognised as a crucial component for progress toward global development outcomes related to education, poverty reduction and gender equality, amongst others.Citation1,Citation2 Given that young people constitute nearly one-fourth of the world’s total population, a focus on this age group is both imperative and inevitable, particularly for India, the country with the largest share of adolescents in the world.Citation3

Peer education is not a new programmatic intervention for SRH. The simplicity and commonsensical nature of its rationale–that young people can more easily reach their peers with education and can discuss sensitive issues with them more easily than adults can–may be behind its prolific use in SRH programming. To place this India-focused systematic review in the context of the wider literature, we appraised the global literature, identifying reviews on the effectiveness of interventions aimed at preventing SRH problems and the behaviours amongst adolescents and young people that contribute to them. Despite the use of peer education globally, the evidence of its contribution to bringing about changes in SRH knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours is mixed.Citation4–37 Further, little to no evidence exists on the possibility of peer education impacting upon other desirable changes, such as the creation of safe spaces, friendship networks, and youth empowerment. Finally, there is limited evidence on the optimal conditions for peer education programmes to be effective. This systematic review thus addresses part of the evidence gap by seeking to understand the inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes of youth peer education interventions undertaken in the Indian context and to gain insights on their effectiveness on the above-mentioned outcomes. Specifically, the review sought to answer the changes that these initiatives have affected in relation to SRH knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of young people. Besides the primary research question, we also addressed additional subquestions:

What was the content of these initiatives?

How were these initiatives delivered (by whom, where, with what support tools)?

In what context were they delivered, i.e. were they part of a wider intervention package?

What was the coverage of these initiatives?

What was the quality of these initiatives?

What other, if any, changes have resulted, e.g. in perception of stronger trust (attitude) and behaviour (help-seeking) from friends?

Methods

Search strategy

Following standard systematic review methodology, the research team developed a protocol to comprehensively collect and analyse evidence related to the research questions.Citation38 As a first step, an expert advisory group was convened to help define key terms for the research (Box 1).Citation39–41 Members of the group included individuals with experience in research and programme implementation on young people’s SRH in India and those with existing relationships with SRH non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Box 1. Key definitions

Sexual health is a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity.

Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.Citation39

Reproductive health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes. Reproductive health therefore implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so. Implicit in this last condition are the rights of men and women to be informed and to have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable methods of family planning of their choice, as well as other methods of their choice for regulation of fertility which are not against the law, and the right of access to appropriate health-care services that will enable women to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth and provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy infant. In line with the above definition of reproductive health, reproductive health care is defined as the constellation of methods, techniques and services that contribute to reproductive health and wellbeing by preventing and solving reproductive health problems. It also includes sexual health, the purpose of which is the enhancement of life and personal relations, and not merely counselling and care related to reproduction and sexually transmitted diseases.Citation39

Bearing in mind the above definition, reproductive rights embrace certain human rights that are already recognised in national laws, international human rights documents and other consensus documents.

These rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. It also includes their right to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence, as expressed in human rights documents.Citation40

Young people are defined as encompassing individuals aged 10–24 years.Citation39, Citation40 This age grouping encompasses both adolescents (10–19 years of age) and youth (15–24 years of age).

Peer education is a strategy whereby individuals from a target group provide information, training, or resources to their peers. These groups can be determined by social or demographic characteristics (e.g. age, education, type of work) or by risk-taking behaviour (e.g. injection drug use, commercial sex work). Peer networks can increase the credibility and effectiveness of the message being presented as they convey information to often hard-to-reach populations. Peer education is widely used and is generally a low-cost intervention. It is a good approach for conveying information in natural settings where target groups are located (e.g. schools, work sites, social gathering places such as parks or clubs), when group members are unlikely to receive services without such an approach, or when a peer is much more likely to appear credible than a non-group member (e.g. among stigmatised groups).Citation41

The search strategy aimed to identify studies and evaluations of initiatives in India that included a component of SRH peer education for young people. Relevant peer-reviewed articles and grey literature (hereinafter referred to collectively as “publications”) were identified using three methods: PubMed and POPLINE database searches; bibliographic reviews; and targeted outreach to organisations. PubMed searches were conducted using the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms “sexual and reproductive health and rights”, “peer education program”, and “young people”. The POPLINE search was done using the main topics and subtopics of this review, along with the key search terms (Box 2). The bibliographies of select articles were then reviewed to identify further publications. The list of relevant organisations to target with outreach was developed in consultation with the expert advisory group and included both youth- and adult-led national and international NGOs and donor agencies.

Inclusion criteria

The research team included publications only if they adhered to all of the following criteria: were studies and evaluations of interventions that took place in India; were published on or after 1 January 2000 and on or before 31 December 2016; the research was initiated on or after 1 January 2000; the intervention included a stand-alone or integrated peer education component focusing on the promotion of young people’s SRH; the target group was young people aged 10–24; measurements on changes in knowledge, attitudes, and/or behaviours were reported; were published in English.

Box 2. Literature search strategy

PubMed searched October 24, 2016: 1302 results

Filters applied: article type (clinical trials, evaluation studies, meta-analysis, review, systematic review), publication dates (2000-2015), species (humans), Languages (English), Ages (child: 6–12 years, adolescent: 13–18 years, young adult: 19–24 years)

(((“Sexual health” OR “reproductive health” OR “reproductive choice” OR “sexual behavior” OR “HIV/AIDS” OR “HIV” OR “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” OR “sexually transmitted infections” OR “maternal health” OR “pregnancy” OR “abortion” OR “contraceptive choice” OR “contraception behavior” OR “family planning” OR “contraception” OR “child marriage” OR “sexual violence” OR “menstrual hygiene” OR “sexuality” OR “gender” OR “gender norm” OR “gender based violence” OR “sexual rights” OR “reproductive rights”)) AND (“peer education” OR “peer group” OR “peer mentored” OR “youth led” OR “youth run” OR “youth informed” OR “participation” OR “involvement” OR “meaningful participation” OR “programs” OR “social participation” OR “leadership” OR “community engagement” OR “process evaluation” OR “health services” OR “behavior” OR “life skills education” OR “comprehensive sexuality education”)) AND (“Adolescent” OR “adolescence” OR “youth” OR “young adult” OR “young adolescent” OR “young”)

POPLINE searched October 25, 2016: 205 results

Filters applied: India, 2000–2015

Main category: Adolescent Reproductive Health

Early and unintended pregnancy

Family Planning Programs and Services

– Community-based Non-formal Education Programs

– Increasing Adolescents’ Participation in Programs

– Increasing Adolescents’ Access to Health Services

– Unmet Need for Family Planning Services

– Youth Friendly Clinic Services

HIV and STIs in Adolescents

Improving Knowledge, Attitudes, and Skills of Adolescents

– Advocacy Campaigns

– Life-Skills Education

– Meeting the Needs of Married Adolescents

– Peer Education

– Youth Clubs/Organisations

Sexual Behaviour

Exclusion criteria

The research team excluded publications that were: secondary analyses of existing data sets for the purpose of presenting integrative outcomes from different research studies or programmes; discussions of literature included in contributions to theory building or critique; summaries of the literature for the purpose of information or commentary; editorial discussions that argue the case for a field of research or course of actions

Data analysis

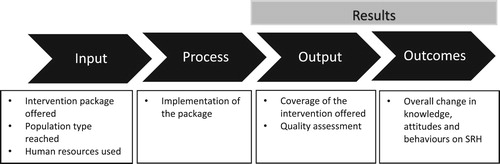

In order to facilitate the data analysis, the research team developed a logic model () which, in turn, formed the basis for the review tables (). We used the standard Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for reporting findings.Citation38 The tabled information includes: geographical location of the study or evaluation; year of completion; name of implementing organisation; objectives of the study or evaluation; implementation (intervention package, target group, and human resources); results (outputs and outcomes); and limitations. Data entered in the review tables () were discussed with all authors to reach a consensus on characteristics and main findings of each publications.

Consistencies and divergences of findings across publications, methodological limitations of existing research, and knowledge and evidence gaps were identified as part of the review and synthesis. However, given the dearth of publications that fit the inclusion criteria and were accessible to the research team, the decision was made not to assess and exclude publications on the basis of quality, as it would have further limited the evidence base. The preliminary findings of the review were discussed and refined in consultation with the expert advisory group.

Findings

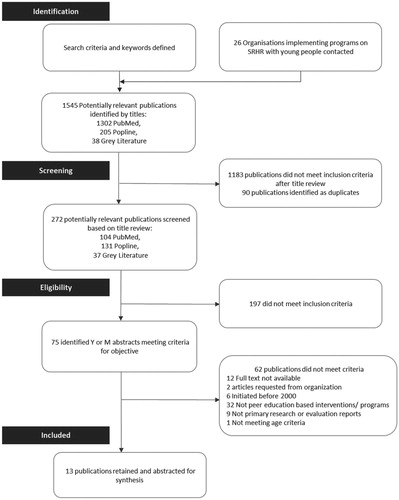

Using the above-mentioned search strategy, the team identified 1545 publications, including 38 from the grey literature (). As a first step, the titles of all publications were screened by two authors, resulting in the exclusion of 1183 that did not meet the inclusion criteria; another 90 duplicates were also removed. As a second step, the abstracts of the remaining 272 publications were screened by the same two authors and categorised into three groups: (1) those that met the inclusion criteria (Y); (2) those for which it was unclear whether or not they met the inclusion criteria (M); and (3) those that did not meet the inclusion criteria (N). Any difference of opinion between the authors was resolved through discussion and consultation. As a third step, the 75 falling into categories Y and M were retrieved and reviewed in full by the two authors, as a result of which 62 were excluded for the following reasons: full text not available (n = 12) or not provided by the concerned organisation (n = 2); research initiated before the year 2000 (n = 6); no peer education based intervention or programme (n = 32); not research studies or evaluation reports (n = 9); or not meeting the age criteria (n = 1). Of the 13 publications in the final list, 9 are peer-reviewed journal papers and 4 are evaluation reports from the grey literature (). As our inclusion criteria include interventions initiated in the year 2000, it is likely that the publications included in this final list are skewed away from the first few years of the review period. Characteristics and main findings of these publications (labelled with letters A-M)Citation42–54 are found in .

Table 1. Literature search results

The work described in the publications (hereinafter referred to as “initiatives”) was geographically distributed across India: two initiatives each in Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal and one each in Bihar, Chandigarh, Goa, and Maharashtra. Two studies reported on initiatives in multiple (two) states–Uttar Pradesh and Delhi National Capital Region (NCR) and Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh, respectively. One study was a pan-India evaluation. Five initiatives were published before 2008, while eight were published between 2008 and 2016.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) carried out 10 of the 13 initiatives. Amongst those, six (A, D-F, H, M) were carried out by indigenous NGOs, one (C) by the Indian chapter of an international NGO, two (I, K) as collaborations between international and indigenous NGOs, and one (G) as a collaboration between the international and Indian chapters of an international NGO. Two initiatives were carried out by academic institutions (B, L), whilst the remaining initiative (J) was carried out by indigenous NGOs in partnership with an academic institution.

The included initiatives fell into three categories: quasi-experimental evaluations (n = 8), descriptive studies (n = 4), and a randomised controlled trial (n = 1) (Supplementary Box S1). The most commonly utilised methodologies were cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. In six of the eight quasi-experimental evaluations, baseline, and endline analyses comparing intervention and control groups were conducted (A-C, G, J, K); the remaining two utilised such comparisons without a control group (E, M). Most quasi-experimental evaluations utilised quantitative measures (A-C, E, G, J, M), although one (K) utilised mixed-methods. The descriptive studies employed quantitative (n = 1) (D), qualitative (n = 1) (H), and mixed-method (n = 2) approaches (F, L). Qualitative studies used in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with beneficiaries and/or key stakeholders such as frontline health workers, programme implementers, government functionaries, family members and community members.

All the initiatives had clearly defined objectives. Nine of the 13 initiatives assessed changes in knowledge, attitudes and perceptions regarding SRH (A-G, J-K), whilst five of them assessed changes in knowledge or utilisation of SRH services (D-F, L-M). Seven assessed changes in attitudes such as gender-equitable attitudes; in perceptions such as emotional health, wellbeing, and improvements in self-confidence and leadership skills; and/or in behavioural outcomes relating to condom and contraception usage, self-reported violence, and substance use (tobacco, cigarettes, or alcohol) (A, G, I, K-M).

Implementation

Across the 13 studies, the implementation of peer education interventions varied widely. The following variables affecting implementation were considered by this review, including: (1) the SRH content of the information provided by peer educators; (2) the wider initiative within which peer education was included; (3) the modes of delivery; (4) the target population groups; and (5) the human resources used to implement the project. These variables are considered in turn below.

Firstly, whilst the exact content of the SRH information provided by peer educators was difficult to determine, the analysis indicates varying degrees of comprehensiveness. This variation in content and delivery of the initiatives and the changes in knowledge and attitudes towards SRH are not comparable. For most initiatives, it is apparent that peer educators provided general reproductive health information, though this was not defined clearly or consistently. Sexual and reproductive health topics common to many of the initiatives were: menstruation, puberty, contraception, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, and pregnancy. Less commonly, the peer educators provided information on birth spacing, laws relating to child marriage and/or abortion, relationships, violence, sexuality, and gender. In most initiatives, peer education expanded beyond SRH to include other public health and development topics too. The most common additional topic covered was nutrition, whilst livelihoods, savings formation, substance use, sports, and adolescent health (general) were addressed by a few initiatives.

Secondly, more often than not, peer education was one amongst several interventions aimed at achieving programmatic objectives related to young people’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours. Out of the 13 initiatives included in this review, two reported the use of peer education as a stand-alone intervention, whilst 11 reported it as one intervention amongst two or more. Each multi-component programme used a combination of interventions in addition to peer education. Some of the additional components were directed at frontline workers, including teacher training (n = 1) and capacity-building for health workers (n = 2), whilst those directed at adolescents included: delivery of educational sessions in schools by teachers or public health nurses (n = 2); livelihoods and/or vocational training (n = 4); savings formation (n = 2); communication skills training (n = 1); community outreach and sensitisation (n = 3); service delivery (n = 1); and sports coaching (n = 1).

Thirdly, between the initiatives, there was great variety in the settings, materials, and delivery modes. The majority were delivered in out-of-school settings in places close to where young people live or congregate, such as community centres, anganwadi centres (type of rural child care centre), and homes of peer educators who work or live in slums. In two initiatives, peer educators were operating in school settings. Whilst most initiatives did not elaborate on the content or format of the materials available for peer educators, one publication mentions the use of a flip book with relevant case studies, whilst others mention training curricula or modules. In relation to delivery modes, in nine initiatives peer educators gave group informational sessions, rather than speaking to young people one-on-one, which was the modality reported in the four remaining publications.

Fourthly, whilst all the initiatives used peer education to reach young people, specific cohorts were targeted through each. The most common group targeted were adolescent girls in the 10–19 age bracket, or a subset thereof. Only two initiatives targeted young men specifically, and one targeted married couples. Most of the initiatives addressed young people younger than 20 years, although four included young people older than this and, in one case, up to 29 years of age. The target groups included a mixture of in-school and out-of-school young people, as well as urban and rural residents. Several of the studies made reference to targeting poor, low-income or slum areas.

Lastly, in addition to peer educators, in multi-component initiatives other cadres of workers were involved in delivering information or complementary interventions. Some initiatives built upon existing parts of the health, community development or education systems in India (e.g. community health workers, anganwadi workers, SABLA Scheme workers, teachers, child development officers) for implementation, whilst others drew upon staff members within non-governmental agencies. Implementing agencies also drew upon their own staff members, in addition to consultants, researchers, and local NGOs, for delivery.

Coverage and quality

Coverage of these interventions was assessed based on the number of people within the target population reached by the peer educators. In 11 initiatives, peer educators reached out to young people who were a part of the intervention, whereas the remaining two initiatives had no information on coverage (C, H). Amongst the 11 initiatives that mentioned coverage, four did not specify the denominator population (D, E, J, M). The scale of these initiatives varied considerably, with the number of young people reached by peer educators ranging from 84 to 4,811,264.

None of the initiatives reported on the quality of the content or delivery of peer education. Five initiatives did conduct process monitoring (A, E, F, H, L). In one of these initiatives, on-site supervision was done along with weekly review meetings to assess intervention delivery quality (A), whereas two further initiatives developed a monitoring mechanism involving multiple stakeholders to ensure effective implementation (F, L).

Changes in knowledge

Whilst 11 publications–including both multi-component and stand-alone peer education initiatives–reported increases in knowledge, just nine reported increases in SRH knowledge. These increases in SRH knowledge related to pubertal changes, menstrual hygiene, reproductive tract infections, STIs, and HIV; the existence of SRH services, including those for adolescents; and SRH practices such as contraceptive use (A-G, J, M). An initiative implemented by the Centre for Catalysing Change (C3) that carried out peer education for married couples in Jharkhand (M) reported significant increases in knowledge between baseline and endline surveys in relation to a variety of different topics, including knowledge of family planning methods (contraceptive pills: 20% to 91%; condoms: 39% to 97%); awareness of pregnancy detection kits (28% to 86%) and their use (20% to 56%); awareness of complications in pregnancy and childbirth often leading to maternal death as a consequence of early pregnancy (wives: 67% to 87%; husbands: 74% to 96%); and awareness of the benefits provided by the Government of India in case of institutional delivery (e.g. free transport to and from the health facility: wives 21% to 100% and husbands 36% to 97%). The Yuva Mitr initiative, implemented by indigenous NGO Sangath, demonstrated that young people reached by peer educators had higher levels of knowledge of and more favourable attitudes toward SRH [OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.06–2.28 (rural community) and OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.09–1.97 (urban community)] in comparison to young people reached by teachers (A).

One of the two stand-alone peer education initiatives reported change in SRH knowledge (J). This initiative assessed changes in HIV and AIDS knowledge and found that young people who received the intervention had higher knowledge scores (p ≤ 0.001). Additionally, young girls scored significantly higher on HIV and AIDS knowledge in comparison to young boys (p < 0.05).

Changes in attitudes

Only four of the 13 initiatives measured changes in SRH attitudes or beliefs (A, J, K, M). Among these, two were stand-alone (J, K) and two were multicomponent (A, M) initiatives. The STEP initiative (J) reported that young people reached by peer educators had significant increases in positive attitudes toward consistent condom use (p < 0.001) and positive beliefs towards people living with HIV (p < 0.001). The Yaari-Dosti initiative, which targeted young men aged 15–29, also reported more positive attitudes towards people living with HIV (p < 0.05) (K). Favourable attitudes were reported by the C3 married couple initiative, which reported changes amongst both young women (46% to 93%) and their husbands (51% to 92%) in relation to attitudes toward visiting a health facility for symptoms of reproductive tract infections (M).

Overall, the two stand-alone (J, K) and one multicomponent (A) initiatives reported statistically significant positive changes in attitudes among young people who received the interventions. One other multicomponent intervention (M) reported positive changes in attitudes; however, the initiative did not provide information on whether those changes were statistically significant.

Changes in behaviours

Seven of the 13 initiatives (A, F-I, K, M) reported changes in behavioural outcomes; however, only four of these initiatives reported changes in SRH-related behaviours—one stand-alone peer education initiative (K) and three multicomponent initiatives (A, F, M). The outcomes reported by the initiatives included increases in reporting sexual health problems or menstrual problems for young women (A, F, K); help seeking from health care providers (A, M); and visiting adolescent-friendly health services for SRH (M). The Yaari-Dosti initiative reported several other behavioural changes, including improvements in communication with one’s partner on condoms, sex, STIs, and/or HIV (p < 0.05); increased condom use (p < 0.05); and positive trends on the Gender-Equitable Men scale scores associated with a decrease in HIV/STI risk behaviours among the young men reached by peer educators (K). Amongst these initiatives, only the stand-alone peer education intervention reported statistically significant changes in behavioural outcomes among young people (K). None of the three multicomponent initiatives reported statistically significant changes in behaviours (A, F, M).

Other changes

In addition to changes in SRH knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours, some initiatives reported knowledge, attitudinal, and behavioural changes in relation to other areas, including gender-based violence, child marriage, livelihood, and savings formation, nutrition, substance use, community sensitisation, and advocacy.

Knowledge

Six of the 13 initiatives reported changes in knowledge on non-SRH-related issues such as nutrition, substance use, emotional health, and gender equity (A, E, F, H, I, L). Four of these initiatives reported increases in knowledge about nutrition, anaemia and/or intake of iron-rich foods and folic acid tablets for young women (E, F, H, L). For example, one initiative reported young people reached by the National Adolescent Health Programme (Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram) in one of the districts had increased knowledge of iron-rich foods (97% vs. 76%); were more likely to have heard of anaemia (89% vs. 48%); received information on nutrition (79% vs. 24%) and were aware of their own weight (75% vs. 62%) compared to those not reached by the national programme (F).

Three of these six initiatives reported increased awareness of the right to education, life skills education, legal age of marriage, and/or various legal and other options for women who experience marital violence (E, F, I). One initiative reported increased knowledge between baseline and endline surveys of the legal age of marriage for girls (30% to 96.5%) and boys (26% to 77%) (E). Another reported higher levels of awareness among young people on their right to education, equal rights between boys and girls and available child protection services (F).

Attitudes

Other than those noted above, the most common attitudinal change affected by the initiatives was in relation to gender equality; three of the 13 initiatives–including one stand-alone peer education initiative (K)–reported statistically significant changes towards egalitarian gender role attitudes and, at the same time, less support for inequitable norms (C, I, K). The Do Kadam Barabari Ke initiative (I), for example, reported that young men reached by peer educators expressed more egalitarian attitudes and notions of masculinity (p = 0.04), rejected men’s or boys’ right to exercise controlling behaviours over women or girls (p = 0.003), and rejected men’s or boys’ right to perpetrate violence on a woman or girl (p = 0.002). Moreover, the young men believed their peers would respect them for demonstrating non-traditional behaviours in at least three of the following four situations: respected by friends if a boy talks about his problems with his friends or peers; helps his mother do her housework; walks away from a fight; and refuses to physically abuse his wife even if she disobeys him (p = 0.04) (I).

Behaviours

Four of the 13 initiatives reported changes in non-SRH behaviours (A, C, G, L), all of which were multicomponent initiatives. Three of these initiatives reported increases in autonomy amongst young women, which was demonstrated by improvements in vocational skills and livelihood activities, work aspirations, physical mobility within the community and/or communication skills (C, G, L). One initiative reported a decrease in the perpetration of physical violence among young people reached by the intervention (A).

Discussion

This paper sets out to answer a set of interrelated research questions regarding the use and effectiveness of peer education in achieving sexual and reproductive health knowledge, attitudinal, and behavioural outcomes in India. Although the quantity and quality of the evidence are limiting, this review has been able to highlight important trends and define a framework for future research.

In relation to the first three additional research questions, this review found that the way in which peer education has been utilised varies greatly in terms of content, delivery, and context in India. There is no standardised model of peer education, and the majority of initiatives combine it with other interventions such as health service delivery, sports coaching or vocational training for young people. The next two additional research questions on coverage and quality were difficult to assess given the dearth of data. Whilst numbers of young people reached through peer education were available for 11 publications–and noteworthy in several–four were missing denominators. Further, the quality of peer education was not assessed systematically in any of the initiatives.

In relation to the changes affected by the initiatives, success varied in terms of impact on SRH knowledge, attitudinal, and behavioural outcomes. In relation to SRH knowledge, nine of the 13 initiatives reported increases, with four of these reporting statistically significant results (A, B, G, J). Of the nine, eight were multi-component initiatives (A-G, M), and one was a stand-alone peer education initiative (J). Changes in SRH attitudes were reported by just four initiatives; two of these were multi-component (A, M) and two were stand-alone (J, K). The two stand-alone (J, K) initiatives and one multicomponent (A) initiative reported statistically significant attitudinal change. Lastly, SRH behavioural outcomes were reported by four initiatives (A, F, K, M), one of which was a stand-alone peer education intervention (K). Only the stand-alone peer education intervention reported statistically significant changes in behavioural outcomes amongst young people (K). Changes in non-SRH knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours were also reported in many publications, and notably so in relation to knowledge of nutrition and changes in gender-equitable attitudes. Overall, changes in the desired direction in relation to knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours occurred in some multicomponent and stand-alone interventions, but not in others.

To place the findings of our India review in perspective, we utilised our global review of reviews (). These reviews were published between 2001 and 2014Citation4–13 and had been cited in two state-of-the-art reviews.Citation14,Citation15 They included published reports of research studies and evaluations carried out in high-,Citation16–27 middle- and low- income countries.Citation28–37 Twenty-two initiatives–10 of which were from low- and middle-income countries–provided information on the effect of peer education interventions when delivered as stand-alone interventions. Changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour as a result of stand-alone peer education are mixed (). Of those initiatives reporting changes, positive results in knowledge were seen in nine of 15 initiatives (60%); in relation to attitudes, positive change was seen in six of 11 initiatives (54.5%); and in relation to behaviour, in six of the 14 initiatives (37.5%). In other words, the global review illustrates that peer education has been shown to be more effective in improving knowledge and attitudes than in promoting healthier behaviours in some initiatives, but not in others, a finding that is consistent with the India review. In the India review, whilst peer education was part of a number of multi-component initiatives in which positive changes were reported, it was also part of initiatives in which such changes were not reported. However, it is worth noting that peer-education-only initiatives from India did report statistically significant results in relation to knowledge (J), attitudes (J, K), and behaviours (J, K).

Table 2. Global review of reviews studies

Table 3. Summary of review findings

Our review of Indian peer-education initiatives did not directly address the optimal conditions for the success of peer education. On the other hand, three other systematic reviews examined what it takes to ensure that peer education programs are effective—Tolli et al., Maticka-Tyndale et al. and Gottschalk et al., although only Tolli et al. did so in any depth.Citation7,Citation10,Citation13 Further research on the optimal conditions for success for peer education is needed to provide solid evidence for designing effective programs in India and across the globe.

Another pertinent research question emerging from both India and global reviews is whether the fields of global health and human rights are measuring the “right” things in relation to peer education. To date, evaluations and research of peer education have judged its effectiveness primarily on changes in knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, and, in some cases, health outcomes. Whilst these measurements are not without value, it is important to further explore the potential of peer education to contribute to a range of desirable health and rights outcomes, including young people’s awareness of their rights to access information and services; legitimation of dialogue on previously-taboo SRH issues; young people’s awareness of where and how to seek help and their confidence in doing so; improvement in communication between peers, as well as between parents and young people; and enhancement of social networks.

Conclusion

Peer education has been employed in India and around the world in a variety of ways to bring about changes in the SRH knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of adolescents and young people. While the published literature on this in the Indian context is uneven in quality, there are clear indications that it has contributed to improvements in these areas in some–but not all–initiatives. Now is not the moment to give up on peer education, but, rather, to better understand the role it could play within public health and human rights initiatives. Taking the next step forward in programming for adolescents and young people in India and globally will require dialogue regarding which outcomes peer education programmes could reasonably be expected to contribute to and the conditions under which they can be achieved.

Acknowledgments

Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli conceived the paper. Suneeta Krishnan, Mariam Siddiqui and Ishu Kataria prepared the first draft. Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli provided feedback; Mariam Siddiqui and Ishu Kataria worked with him to prepare the second draft. Suneeta Krishnan dropped out of the process. Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli then worked with Mariam Siddiqui, Ishu Kataria and Katherine Watson to prepare the final draft. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Supplementary Box S1

Download MS Word (59.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1741494

Additional information

Funding

References

- Deutsche Stiftung Weltbevölkerung. Sexual and reproductive health and rights and the global goals. 2016; [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: http://www.dsw.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/SRHR-and-the-SDGs.pdf.

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. Sustainable development goals: a SRHR CSO guide for national implementation. 2015; [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/sdg_a_srhr_guide_to_national_implementation_english_web.pdf.

- Dasra. Body of knowledge: improving sexual and reproductive health for India’s adolescents; 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.dasra.org/resource/improving-sexual-and-reproductive-health-for-adolescents.

- Blank L, Baxter SK, Payne N, et al. Systematic review and narrative synthesis of the effectiveness of contraceptive service interventions for young people, delivered in educational settings. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(6):341–351.

- Blank L, Baxter SK, Payne N, et al. Systematic review and narrative synthesis of the effectiveness of contraceptive service interventions for young people, delivered in health care settings. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(6):1102–1119.

- Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, et al. The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: two systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(3):272–294.

- Gottschalk LB, Ortayli N. Interventions to improve adolescents’ contraceptive behaviors in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the evidence base. Contraception. 2014;90(3):211–225.

- Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S. Peer-delivered health promotion for young people: A systematic review of different study designs. Health Educ J. 2001;60(4):339–353.

- Kim CR, Free C. Recent evaluations of the peer-led approach in adolescent sexual health education: a systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(3):144–151.

- Maticka-Tyndale E, Barnett JP. Peer-led interventions to reduce HIV risk of youth: a review. Eval Program Plann. 2010;33(2):98–112.

- McQueston K, Silverman R, Glassman A. The efficacy of interventions to reduce adolescent childbearing in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Stud Fam Plann. 2013;44(4):369–388.

- Medley A, Kennedy C, O'Reilly K, et al. Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3):181–206.

- Tolli MV. Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention, adolescent pregnancy prevention and sexual health promotion for young people: a systematic review of European studies. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(5):904–913.

- Chandra-Mouli V, Lane C, Wong S. What does not work in adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A review of evidence on interventions commonly accepted as best practices. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(3):333–340.

- Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. Our future: a lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423–2478.

- Smith MU, Dane FC, Archer ME, et al. Students together against negative decisions (STAND): evaluation of a school-based sexual risk reduction intervention in the rural south. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(1):49–70.

- Ferguson SL. Peer counseling in a culturally specific adolescent pregnancy prevention program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(3):322–340.

- Brindis CD, Geierstanger SP, Wilcox N, et al. Evaluation of a peer provider reproductive health service model for adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(2):85–91.

- Borgia P, Marinacci C, Schifano P, et al. Is peer education the best approach for HIV prevention in schools? findings from a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36(6):508–516.

- Stephenson J, Strange V, Allen E, et al. The long-term effects of a peer-led sex education programme (RIPPLE): a cluster randomised trial in schools in England. PLoS Med. 2008;5(11):e224, discussion e224.

- Kleiber D, Appel E. Evaluation des Modellprojektes Peer Education im Auftrag der BzgA. Koln: Bundeszentrale fur gesundheitliche Aufklarung; 2001.

- Merakou K, Kourea-Kremastinou J. Peer education in HIV prevention: an evaluation in schools. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(2):128–132.

- Caron F, Godin G, Otis J, et al. Evaluation of a theoretically based AIDS/STD peer education program on postponing sexual intercourse and on condom use among adolescents attending high school. Health Educ Res. 2004;19(2):185–197.

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, et al. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):177–186.

- Mellanby AR, Rees J, Tripp JH, et al. A comparative study of peer-led and adult-led school sex education. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(4):481–492.

- Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment project: a community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(8):1129–1136.

- Ozer EJ, Weinstein RS, Maslach C, et al. Adolescent AIDS prevention in context: the impact of peer educator qualities and classroom environments on intervention efficacy. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25(3):289–323.

- Agha S, Van Rossem R. Impact of a school-based peer sexual health intervention on normative beliefs, risk perceptions, and sexual behavior of Zambian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(5):441–452.

- Cartagena RG, Veugelers PJ, Kipp W, et al. Effectiveness of an HIV prevention program for secondary school students in Mongolia. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(6):925.e9–925.e16.

- Brieger WR, Delano GE, Lane CG, et al. West African youth initiative: Outcome of a reproductive health education program. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(6):436–446.

- Merati TP, Ekstrand ML, Hudes ES, et al. Traditional Balinese youth groups as a venue for prevention of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl 1):S111–S119.

- Nastasi BK, Schensul JJ, De Silva MWA, et al. Community-based sexual risk prevention program for Sri Lankan youth: influencing sexual-risk decision Making. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1998;18(1):139–155.

- Speizer IS, Tambashe BO, Tegang SP. An evaluation of the “Entre Nous Jeunes” peer-educator program for adolescents in Cameroon. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(4):339–351.

- Mitchell K, Nyakake M, Oling J. How effective are street youth peer educators?: Lessons learned from an HIV/AIDS prevention programme in urban Uganda. Health Educ. 2007;107(4):364–376.

- Gao Y, Shi R, Lu Z, et al. An effective Australian-Chinese peer education program on HIV/AIDS/STDs for university students in China. J Reprod Med. 2002;11(Suppl 1):7–12.

- Kinsler J, Sneed CD, Morisky DE, et al. Evaluation of a school-based intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention among Belizean adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2004;19(6):730–738.

- Ozcebe H, Akin L, Aslan D. A peer education example on HIV/AIDS at a high school in Ankara. Turk J Pediatr. 2004;46(1):54–59.

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Br Med J. 2015;349:g7647.

- World Health Organization. Sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health: an operational approach; 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258738/9789241512886-eng.pdf;jsessionid=783755057698F07ED34A9D5BE849B19C?sequence=1.

- World Health Organization. Reproductive health strategy; 2004 [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68754/WHO_RHR_04.8.pdf;jsessionid=5238C75726FB8FF44F6DAC0AF0B3B912?sequence=1.

- Horizons Program. Peer education—rigorous evidence, usable results; 2010 [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/research-to-prevention/publications/peereducation.pdf.

- Balaji M, Andrews T, Andrew G, et al. The acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of a population-based intervention to promote youth health: an exploratory study in Goa, India. J Adoles Health. 2011;48(5):453–460.

- Parwej S, Kumar R, Walia I, et al. Reproductive health education intervention trial. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72(4):287–291.

- Sebastian MP, Grant M, Mensch B. Integrating adolescent livelihood activities within a reproductive health programme for urban slum dwellers in India. New Delhi: Population Council; 2005.

- YP Foundation. Advancing leadership and life skills to enable young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health information and services. programme closure report (September 2014–January 2016). 2016.

- Child In Need Institute (CINI). Making a difference 2012–15: advancing young people’s reproductive and sexual health and rights though a government-civil society partnership in four districts of West Bengal, India. CINI; 2015.

- Child In Need Institute (CINI). Report on the impact assessment of the project strengthening Rashtriya Kishore Swasthya Karyakram through government civil society partnership in West Bengal. 2016.

- Mensch BS, Grant MJ, Sebastian MP, et al. The effect of a livelihoods intervention in an urban slum in India: do vocational counseling and training alter the attitudes and behavior of adolescent girls? New Delhi: Population Council; 2004.

- Centre for Development and Population Activities (CEDPA). SABLA—improving well being of adolescent girls to improve their health, economic and education status. Achievements and challenges in the implementation of SABLA scheme in Jharkhand. CEDPA; 2013.

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Gogoi A, Zavier AJF, et al. The effect of a gender transformative life skills education and sports coaching program on the attitudes and practices of adolescent boys and young men in Bihar. New Delhi: Population Council; 2016.

- Chhabra R, Springer C, Rapkin B, et al. Differences among male/female adolescents participating in a school-based Teenage Education Program (STEP) focusing on HIV prevention in India. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(2 Suppl 2):S2-123-127.

- Verma R, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra VS, et al. Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India. Horizons Final Report. Washington, DC: Population Council; 2008.

- Administrative Staff College of India. Evaluation of SABLA scheme: a report submitted to ministry of women and child development. Hyderabad: Government of India; September 2013.

- Centre for Catalyzing Change. Endline evaluation report on ‘addressing the reproductive health needs and rights of married adolescent couples’. May 2015.