Abstract

Expanding access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services is one of the key targets of the Sustainable Development Goals. The extent to which sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) targets will be achieved largely depends on how well they are integrated within Universal Health Coverage (UHC) initiatives. This paper examines challenges and facilitators to the effective provision of three SRHR services (maternal health, gender-based violence (GBV) and safe abortion/post-abortion care) in Ghana. The analysis triangulates evidence from document review with in-depth qualitative stakeholder interviews and adopts the Donabedian framework in evaluating provision of these services. Critical among the challenges identified are inadequate funding, non-inclusion of some SRHR services including family planning and abortion/post-abortion services within the health benefits package and hidden charges for maternal services. Other issues are poor supervision, maldistribution of logistics and health personnel, fragmentation of support services for GBV victims across agencies, and socio-cultural and religious beliefs and practices affecting service delivery and utilisation. Facilitators that hold promise for effective SRH service delivery include stakeholder collaboration and support, health system structure that supports continuum of care, availability of data for monitoring progress and setting priorities, and an effective process for sharing lessons and accountability through frequent review meetings. We propose the development of a national master plan for SRHR integration within UHC initiatives in the country. Addressing the financial, logistical and health worker shortages and maldistribution will go a long way to propel Ghana’s efforts to expand population coverage, service coverage and financial risk protection in accessing essential SRH services.

Résumé

Élargir l’accès à la santé et aux droits sexuels et reproductifs est l’une des principales cibles des objectifs de développement durable. La mesure dans laquelle les objectifs en matière de santé et droits sexuels et reproductifs seront réalisés dépend de leur plus ou moins grande intégration dans les initiatives en faveur de la couverture santé universelle (CSU). Cet article examine les facteurs qui contrarient ou facilitent la prestation de trois services de santé sexuelle et reproductive (santé maternelle, violences sexistes et soins d’avortement sûr/post-avortement) au Ghana. L’analyse effectue une triangulation des données tirées d’un examen des documents avec des entretiens qualitatifs approfondis avec des parties prenantes et adopte le cadre de Donabedian pour évaluer la prestation de ces services. Les points essentiels parmi les difficultés identifiées sont l’insuffisance du financement, la non-inclusion de certains services de SSR, notamment la planification familiale et les services d’avortement/post-avortement, dans le panier de soins de santé et les frais cachés pour les services maternels. Le manque de supervision, la mauvaise répartition de la logistique et du personnel de santé, la fragmentation des services d’appui pour les victimes de la violence sexiste entre les organismes sont aussi problématiques, de même que les croyances et pratiques socio-culturelles et religieuses qui influent sur la réalisation et l’utilisation des services. Parmi les facteurs qui facilitent une prestation efficace des services de SSR figurent la collaboration et le soutien des acteurs, une structure du système de santé propre à appuyer la continuité des soins, la disponibilité de données pour surveiller les progrès et définir les priorités, et un processus bien conçu de partage des leçons et de redevabilité grâce à de fréquentes réunions d’analyse. Nous proposons la mise au point d’un plan-cadre national pour l’intégration de la SSR dans les initiatives de CSU dans le pays. En s’attaquant à la mauvaise répartition des ressources et aux lacunes financières, logistiques et relatives aux agents de santé, on pourra faire beaucoup pour stimuler les activités du Ghana afin d’élargir la population desservie, la couverture des services et la protection contre le risque financier dans l’accès aux services essentiels de SSR.

Resumen

Una de las principales metas de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible es ampliar el acceso a los servicios de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SDSR). El grado en que se lograrían las metas de SDSR depende en gran medida de cuán bien son integradas en las iniciativas de Cobertura Universal de Salud (CUS). Este artículo examina los retos y facilitadores de la prestación eficaz de tres servicios de SDSR (salud materna, violencia de género (VG) y aborto seguro/atención postaborto) en Ghana. El análisis triangula la evidencia de la revisión de documentos con entrevistas cualitativas a profundidad con las partes interesadas y adopta el modelo Donabedian para evaluar la prestación de estos servicios. Entre los retos identificados, los más importantes son: financiamiento inadecuado, la no inclusión de algunos servicios de SDSR tales como planificación familiar y servicios de aborto/atención postaborto en el paquete de beneficios de salud, y cargos ocultos por servicios de salud materna. Otros problemas son: mala supervisión, mala distribución de personal de logística y de salud, fragmentación de los servicios de apoyo para las víctimas de VG entre diferentes instituciones, y creencias y prácticas socioculturales y religiosas que afectan la prestación y utilización de los servicios. Los facilitadores que resultan prometedores para la prestación eficaz de servicios de SDSR son: colaboración y apoyo de las partes interesadas, estructura del sistema de salud que apoya el continuum de servicios, disponibilidad de datos para monitorear el progreso y establecer prioridades, y un proceso eficaz para compartir lecciones y rendición de cuentas por medio de reuniones de revisión frecuentes. Proponemos la formulación de un plan maestro nacional para la integración de SDSR en las iniciativas de CUS en el país. Abordar la mala distribución e insuficiencias financieras, logísticas y de trabajadores de salud contribuirá en gran medida a impulsar los esfuerzos de Ghana para ampliar la cobertura de la población, la cobertura de servicios y la protección de riesgos financieros para acceder a los servicios esenciales de SDSR.

Background

There exist inexpensive and effective interventions to help women go through pregnancy and childbirth safely, prevent unintended pregnancies, offer safe abortions, and avoid and treat sexually transmitted diseases. Despite these, unsafe sex is the second highest risk factor for death and disability in the poorest communities of the world.Citation1 Each year, about 214 million couples in developing countries face unmet need for contraception,Citation2 about one in four pregnancies are unintended/unplanned,Citation3 and 25 million unsafe abortions occur. In addition, 810 women die every day from pregnancy and childbirth-related complications.Citation4 Each day, about 1 million sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are acquired and each year there are an estimated 376 million new cases of infections with one of these four STIs: chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichomoniasis, which could have easily been prevented.Citation5 In addition, about 200 million women alive today have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM), a practice that has no health benefits, and is a violation of their human rights. Treating health complications related to FGM also costs about $1.4 billion per year globally.Citation6

Despite their extreme importance, there has not been sufficient funding to increase access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for most people across the globe. This is even more pronounced in lower-and middle-income countries where funding for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) is largely donor driven.Citation7 Some organisations, including PATH, reported a large financing shortfall for family planning, with an estimated annual funding gap for eliminating preventable maternal, child, and adolescent deaths of about US$33 billion globally.Citation7 Thus the responsibility for upholding SRHR ultimately lies with national leaders, who must develop strategies for ensuring sustainable financing in relation to universal health coverage (UHC) and access to SRH services, including family planning.Citation7

Ensuring universal access to SRH services is one of the main targets of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3.7 and 5.6).Citation8,Citation9 In addition, the World Health Organization’s 13th General Programme of Work provides a strategic focus on UHC with specific reference to SRHR.Citation10 This presents an important opportunity to ensure SRH services are incorporated into initiatives aimed at achieving UHC at global, regional and country levels.

Since Independence in 1957, Ghana, has signed onto several treaties aimed at advancing SRHR. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966, the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women of 1979, the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development,Citation11 the Family Planning Costed Implementation PlanCitation12 (arising from FP 2020) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development are a few prominent international treaties Ghana has signed onto which seek to improve SRHR.Citation13 In the country, some health-related policies and strategies have highlighted SRHR issues and provided action plans for their inclusion within broader health programmes. Key among these are: National Reproductive Health and Service Policy and Standards,Citation14 National HIV and AIDS, STI Policy, Ghana National Condom and Lubricant Programming Strategy, the National Gender and Children Policy, the Ghana National Reproductive Health Commodity Security Strategy 2011–2016, among many others.

These policies, along with health systems reforms, improvements in human resource capacity and distribution, infrastructure, logistics and supplies, and health information systems, have led to modest improvements in SRH indicators, but vast disparities exist across the country. For instance, under-five mortality is 52 per 1000 live births while the maternal mortality rate is 310 deaths per 100,000 live births. These are both higher than the MDG targets that were to be attained in 2015. The teenage pregnancy rate is 14% (not changed since 1998) and modern contraceptive use prevalence rate is 20%.Citation15 Coverage of skilled birth attendance is 60% in rural areas compared to 90% in urban settings. Also, nearly all mothers among the richest households (98%) made at least four ANC visits, compared to 76% of mothers from the poorest households.Citation15 Only 47% of deliveries in the poorest households had a skilled attendant at birth, compared to 97% of deliveries in the richest households.Citation15

With the global momentum and efforts towards the achievement of universal health coverage, it is expedient to ensure that SRH programmes and services are integrated within UHC initiatives. This paper investigates the challenges and facilitators of integrating SRHR policies and services into UHC initiatives within Ghana’s health sector. Due to the wide range of SRHR issues, this paper focuses on three SRH services as tracers: specifically, maternal and child health, abortion/post-abortion care, and support for GBV victims. Understanding the challenges and facilitators to the provision of these important SRH services would help prioritise interventions aimed at improving SRHR in Ghana and other developing countries desirous of improving the SRHR of their citizenry.

Conceptual framework

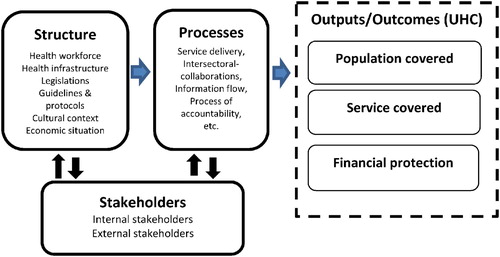

presents the conceptual framework guiding the analysis of this study, which is based on the Donabedian Structure-Process-Outcome (SPO) modelCitation16 and WHO attributes of UHC outcomes to entail proportion of population covered, range of service coverage and financial protection provided.Citation17 The authors postulate that “Structure” in terms of health system infrastructure; health workforce availability and distribution; the legal framework in the country; policies, guidelines and protocols for implementing specific health programmes; social, cultural and religious context; and the economic situation, among others, impact directly on “Process”. The processes here have to do with service delivery, information flow, intersectoral collaborations, and the process for accountability, which impact on the outcomes of UHC in relation to the programmes (specifically maternal and child care, abortion / post-abortion care; and GBV).

Figure 1. Influence of stakeholders, structure and processes on UHC outcomes; a conceptual framework

Stakeholders (both internal and external) are crucial in shaping the “structure” and “process” to improve the main outcome measures. While internal stakeholders are healthcare providers and health managers who oversee and /or provide the services, external stakeholders through acts of advocacy and resource provision play a key role in contributing to improved service coverage, population coverage and financial protection by influencing “structure” and “process” pathways.

Methods

Study setting

Ghana has a population of about 30 million people. Administratively, the country is sub-divided into 16 regions, and 216 districts.Citation18,Citation19 Ghana’s female population is slightly higher than the male (50.8% vs. 49.2%) and about 56.1% of the population live in urban settlements.Citation19 Life expectancy is 63 years while total fertility currently is 4.0.Citation15,Citation20 Maternal and child mortality are relatively high. The main causes of maternal deaths in Ghana are obstetric haemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, abortion-related complications and infectious diseases.Citation15,Citation21 Under-five mortality is higher in rural settings (56 deaths per 1000 live births) compared to urban settings (48 deaths per 1000 live births). Childhood mortality is also disproportionately distributed among the regions of the country with the Greater Accra region having the lowest rate of 42 deaths per 1000 live births while the Upper West region (Ghana’s poorest region) has the highest under-five mortality rate of 78 deaths per 1000 live births.Citation15 Antenatal care (ANC), child health care (vaccinations etc.) and nutrition services are largely supported with donor funds and are free, but the concern is whether the gains could be sustained as donors support dwindles.Citation22

Study design

This is mainly a qualitative research study triangulating information from document review and in-depth interviews. Data was collected through in-depth stakeholder interviews and desk review. The desk review applied the use of relevant key words and Boolean operators to search and retrieve relevant documents including research reports, peer reviewed articles, and policy and legal documents related to SRHR in Ghana. In addition, annual reports and websites of key institutions in Ghana’s health sector were included in the review (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 provide more information on the keywords and websites that were searched and a list of documents reviewed). Since qualitative research is not aimed at achieving randomness but at gaining a deeper understanding of the issues,Citation23 purposive sampling was employed to select individuals to participate in the in-depth interviews. Key informants were purposively selected from the level of policy decision-making and programme implementation from government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and civil society organisations (CSOs), including the Ghana Health Service (GHS), Ministry of Finance, Population Council, and multilateral organisations including Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana, Marie Stopes International, UNFPA and UNICEF.

Data collection and analysis

Primary data was collected mainly through key informant interviews conducted between January and February 2020 with persons who have in-depth knowledge of SRHR issues in Ghana. Twelve respondents who are involved or have been involved in either decision-making or implementation of SRHR programmes or in advocacy for the implementation of SRHR policies or programmes in Ghana were interviewed. To select the participants for the in-depth interviews, letters were sent to the targeted institutions and scheduled officers with deeper insights into the issues were selected. In some instances, institutions requested the interview guide to enable them to understand the issues for discussion and to select the most suitable person for interview.

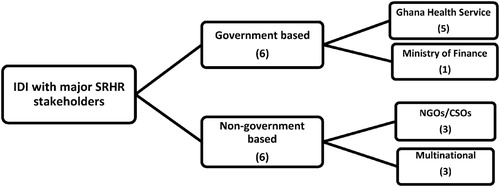

To ensure data quality, experienced researchers with the requisite skills in qualitative research were deployed after undergoing a three-day intensive training. The training allowed the research team to thoroughly review the interview guide and to be conversant with the questions and develop a common understanding of questions and probes before going to the field. The interview guide was first pre-tested with lower-level healthcare managers to ascertain the validity of the questions, after which it was appropriately revised and made ready for data collection. The interviews were tape-recorded. depicts the categories of stakeholders who were interviewed.

The tape-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by experienced researchers. Quality of transcripts was validated by swapping tapes among transcribers and listening to check for accuracy of content. The validated transcripts were then organised and coded thematically. Results from the stakeholder interviews were triangulated with findings emanating from the desk review to improve validity of results. Our triangulation involved a point-by-point comparison of results with the aim of identifying convergent issues from both data sources that serve as either facilitators or challenges to the effective provision of SRHR services in Ghana. This approach to triangulation is a within-method data source triangulation since both in-depth interviews and desk review are qualitative methods but different approaches to data collection and processing.Citation24–26 Analysis took into consideration our conceptual framework thus: results are presented based on the facilitators and challenges with regards to “structure” and “process” issues.

Ethical considerations

The study obtained ethical clearance from the Ghana Health Service Ethical Review Committee (GHS –ERC024/10/19) and the World Health Organization’s Ethics Review Committee (WHO ERC.0003365). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the in-depth interviews. Data was analysed and presented in a manner to preserve anonymity and confidentiality of study participants.

Results

The results examine challenges and facilitators for the effective provision of SRH services including maternal and child health, safe abortion/post-abortion care and GBV services in Ghana, triangulating evidence from document review and in-depth interviews by taking into consideration the Donabedian model of structure and processes leading to key UHC outcomes for SRHR.

“Structure” facilitators

The Ghana Health Service is the main health sector agency responsible for providing maternal and child health services, and abortion/post-abortion care through its health delivery structures in the country. The GHS collaborates with other partners such as the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, the Domestic Violence and Victim Support Unit (DOVVSU) of the Ghana Police Force and other agencies to ensure that survivors of GBV in the country receive the necessary support including healthcare services. Other partners support various components of these services including the development of guidelines and protocols, particularly for maternal and child health, and ensuring that services are consistent with international best practices as well as supporting implementation of specific programmes of interest including trainings and provision of logistics.Citation27

“We did not directly provide help; our help was in the area of ensuring that we develop tools that can be used to make sure that the quality standards are adhered to. There are other agencies that support financially and they play a more active role.” (Development partner official)

“I won’t say that we can attribute all the achievement to us but we have played a major role to make sure that on the universal health coverage, the aspect of reproductive and sexual health we played the little role to help.” (NGO in Health 1)

The availability of the requisite information through national surveys such as the maternal health survey,Citation15 Demographic and Health Surveys, (DHS)Citation20 and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS)Citation28 among others, and the district health information management system have been crucial in facilitating the identification of gaps for effective service provision.Citation29 Aside the information, there is also a cadre of health staff capable of implementing maternal and child health, safe abortion and post-abortion interventions at all levels of health care delivery as well as a strong partnership among the health sector community.

“I believe that the maternal health survey of 2017 even though it served as an end line survey to the MDGS, it served also as a baseline for the sustainable development goals. And so all the indicators of SRH; these are the family planning care, antenatal care, postnatal care, newborn care, HIV aids and all those things … provide a good baseline from where we can build on towards 2030.” (Program Officer, Ghana Health Service)

“And so access to information is important, access to resources, access to technical capacity and all others are all enablers that would help you achieve universal health coverage and also looking at partnerships.” (CSO official)

Another important facilitator for the implementation of maternal and child health programmes is the good reputation Ghana enjoys among the league of network nations in the sub-region who are implementing the WHO quality of care standards for maternal and newborn health care.Citation30 The programme sets standards for the provision of care and experience of care towards reducing maternal and newborn deaths by half by the year 2021.

“Ghana is named as one of the nine African countries implementing the quality of care network which is being supported by WHO. It is about the quality of care for maternal and newborn health care. It is forming district networks that can help to address issues when it comes to maternal and newborn health and some set of standards have been set … this quality of care program is aimed at capacity building networks of staff within these districts networks that have been created.” (Program Officer, Ghana Health Service)

In addition, Ghana has an elaborate health care delivery structure, including referral systems for delivering healthcare services, and particularly maternal and child healthcare services, from the primary through to the tertiary level such that if particular services are not provided at one level of the health care delivery system, they are available on the next level.Citation31 Apart from the health system structure as an enabling factor, there is also a clientele of health care seekers who are willing and able to access maternal and child health services, as coverage for some of these services has grown over the years.

“There are people who understand the concept of sexual and reproductive health and how it fits into universal health coverage and how it has been translated to the various managers and service providers. The other enabler is the fact that you can go through the continuum of care from the community level, all through to the highest level, to get the services depending on what the person needs. … Then, you can get the simplest and the most complex things done within the health system.” (Former Director, Ghana Health Service)

Another important enabler for the implementation of care for safe abortion and GBV is the promulgation of legislation and establishment of a legal framework to ensure that such services are made available, accessible and acceptable to those who need them and that those who violate the rights of others in this respect are punished.Citation13 For instance, besides the 1992 Constitution of Ghana, which guarantees the rights of citizens including women and children, additional laws, such as the Domestic Violence Act, 2007 (Act 732), the Provisional National Defense Council Law (PNDCL) 102 of 1985, and the Criminal Code (Amendment) Act, 2007 ACT 741 have been enacted to promote SRHR. For example, the (PNDCL) 102 of 1985 which amended Act 29, Section 58 of the Criminal Code of 1960 makes abortion legally permissible if the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, or if the pregnancy is a threat to the health of the mother or the foetus.Citation13

To enforce GBV laws and prosecute perpetrators, the government established three “specialised domestic courts” in order to expedite the adjudication of domestic violence cases.Citation32 Again, through social intervention programmes, the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection has put in place a Domestic Violence Board and Secretariat and a domestic violence fund to assist domestic violence victims with skills training and medical bills. Also, the Department of Social Welfare has trained social workers who conduct investigations and counsel victims of domestic violence.Citation32

“Process” facilitators

Frequent review meetings and joint conferences by SRH service providers and programme implementers is one of the key process facilitators for effective delivery of maternal and child health, safe abortion and post-abortion care and GBV programmes in Ghana.Citation29,Citation33

“ … Frequently, we do reviews for those doing reproductive health, and sometimes in the form of conferences they bring them in and they will review their performance. … they are key people apart from those at the ministry level, they also do some monitoring and if you look even at the health summit, the holistic assessment report, you will see that it is partly done by most of the staff from the Ghana Health Service who will carry it out and then present at the health summit.” (Former Director, Ghana Health Service)

A key milestone in SRHR programme implementation in Ghana is the fact that most services, including abortion services, are being carried out at the lower level of care (the community-based health planning and services programme – CHPS) which makes it accessible to rural people.Citation34

“ … In Ghana, you find the doctors almost always in the city, so making the provision of abortion services by midwives for example made it so easy for people to go into health centers in their villages, even the CHPS compounds that have got midwives to have the services and that really changed the whole atmosphere.” (NGO in Health Official 1)

Good results emanating from the district health information system and surveys are also serving as motivation for stakeholders implementing SRHR programmes in the country.

“ … Seeing the results of implementation, some of the initiatives that we put across we’ve seen that they do show very good results so that is more of the motivation factor. If the data is showing that we are making improvement then there is the need to continue and even focus more on those areas.” (Development partner official 1)

Yet another enabling factor for safe abortion and post-abortion care service provision is the fact that some NGOs in health are able to build strong community stakeholder collaboration by involving community members such as women group leaders, community champions and peer educators which facilitates the provision and access of some reproductive services such as abortion and family planning services.

“Oh yes, we thought that the committee champions were our enablers, we also have people we call champions … The Champions were people when if politically people are being difficult we use such champions to try to soften the grounds for us. The Champions were very seasoned and respected individuals who believed in the rights of a woman.” (NGO in Health official 1)

“Structure” challenges

One of the biggest challenges for the implementation of SRH services, including maternal and child health, safe abortion and post-abortion care and GBV, is the lack of adequate funding for implementing and sustaining these activities in the country.Citation22,Citation35 Family planning, safe abortion, post-abortion services and referral services are not covered under the national health insurance benefits package. Funding for most reproductive health programmes including abortion care is largely donor-driven, and most often donor funds are not national in character, but for targeted interventions and communities. Unfortunately, donor funding is now dwindling.Citation22 Moreover, a large chunk of the health sector budget of the Ministry of Health goes into payment of salaries and emoluments and conferencing with virtually nothing left for health promotion and delivery.Citation22

“ … you know currently 95% of budget to Ministry of Health is going to pay emoluments, salaries, so how much of that money would be used to promote health? … all that money for the Ministry of Health is going to pay emoluments and the rest are going to conferences and all that.” (NGO in Health 1)

“ … you can’t continue to depend on donors. In Ghana the domestic resources to the health sector is not very much encouraging. I’m told they said 15% of Abuja, we are not meeting that. Even 5% of GDP we don’t meet that too. And so domestic resources to health is where our concentration is now and globally there have been discussions because a lot of donor funding is reducing and so we have to look at ways of mobilizing our own resources to move on.” (CSO official)

“ … some of the barriers are financing – financing to put things in place at the various levels for the various ages and for the various components of sexual and reproductive health. The other thing is that the financing of the services under NHIS, it doesn’t cover everything, the other thing with SRH as I told you, we wanted the family planning to be covered, but when you sit down and you look at it, you will say ah, who should pay for you to go and have sex?” (Former Director, Ghana Health Service)

Some reproductive health interventions that were piloted and rolled out with support from donor partners in some districts and regions and proven to be successful could not be sustained or scaled up to other districts or regions because government does not have the necessary funds to continue with them.

“UHC is something that I would not say we have attained so it is a process. For us the main challenge is scaling of best practices for we really do support initiatives and this demonstrates practices that work. The challenge is the government having the available funding and resources to continue. So we can have results in a few areas but for UHC, best practices should be scaled up at the national level.” (Development partner 1)

There is also the absence of a national plan for the implementation of SRHR activities. Thus, donors to a large extent determine which reproductive health activities are carried out and each donor decides which component they want to support. This leads to overconcentration on some segments of reproductive health services to the neglect of others.

“ … because we don’t have that kind of master plan that includes all these departments, … for now it’s all like, the Ministry of Health have their plan, Ministry of Gender and Social Protection etc all have their plan, and everybody has got his own plan, that is the way I see it, and we are hoping that all of them will come together without any conscious effort of bringing them together, do you get the point?” (NGO in Health 2)

Socio-cultural and religious factors such as myths, stigma and misconceptions negatively affect the provision and uptake of some reproductive health services.Citation36 Services such as abortion and family planning (e.g. vasectomy) are being stigmatised. Besides that, it was also observed that some providers of abortion services were reportedly beaten up in some circumstances.

“We have people who are worried about myths and misconceptions about family planning methods or even other aspects of sexual reproductive health. There is a lot of stigma on some of the services like abortion … . You should get people who are also looking at different sexual orientations and things which we are not used to as our norms. Some of our people are being beaten up. Some things like vasectomy, in Ghana people shun it.” (Former Director, Ghana Health Service)

“ … we are in a country where everything is being spearheaded by pastors or whatever. You will find somebody coming to the hospital to deliver and the person will tell you, oh my pastor says this one nobody should touch me with the blade, no operation, my pastor says because of this and that I should be able to deliver without any operation and if such a woman dies in the process. So this is a system that is not about money, not about physical structure, not about road but about something in the mind, the religiosity and the cultural thing that is preventing our people from accessing health.” (NGO in Health 1)

In addition, the cost of providing abortion services in some facilities is too high for some clients thus affecting the provision of and access to these services as they are not covered under the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) benefits package. Moreover, some service providers’ religious inclinations prohibit them from providing abortion services and legal and professional ethical standards do not mandate provision in cases of conscientious objection.

“The main challenge has been stigma and also the fact that some service providers charge exorbitant prices for service provision. … there was one individual who was a Regional Director who prevented us from doing it (providing SRHR services) because his religion or he says his religion is in conflict with anything to do with sexual reproductive health services.” (NGO in Health 1)

“ … so even though we are saying that people are coming, there are still others who are surrounded by a lot of religious beliefs during the time of birth. So it becomes a problem when people refuse services like the caesarean section on account that they have not been given the go ahead by their prophet or spiritual leader. That is just an example. There are so many things that we are battling with.” (Program Officer, Ghana Health Service)

“The debatable thing is that we have a comprehensive abortion package which is within the confines of the laws of Ghana. But the word abortion is a very sensitive word and is not always being mentioned, there is an abortion law that the policy of the comprehensive abortion care is under. So that service package is within that provision. And if we don’t pay attention to it as a nation, the health of women would not improve and the maternal mortality would still be a problem because causes of mortality are not only in the pregnancy but for the lack of family planning, there is the problem of an unmet need for family planning.” (Program Officer, Ghana Health Service)

The health system structure and administrative procedures are another challenge confronting the implementation of SRH services including abortion care and GBV. The health system administration arrangement of distributing resources to lower levels of health care delivery through routine bureaucratic administrative procedures poses challenges for the implementation of SRHR programmes. Apart from delays emanating from getting resources to the lower levels, there is also the likelihood that some of the resources may not arrive whole. In addition, others were of the view that government allocation to SRH services should be increased because there is over-reliance on donor partners to fund SRHR activities, and that they should be decentralised to let the lower level of health care have direct access to their allocation for their operations.

“You see for the health system’s capacity at the lower level, access to resources and other things like money is very low. I think a lot of things are concentrated at the national level and so there should be effective decentralization. They should have the resources to work because the services are needed more at the community level. If we are able to allocate more resources to the lower levels to work, a lot of things would change better than allowing money to sit here to be transferred through national to regional before small money gets there … It should not be donor money but our own. How is the government increasing resources to help? They would always say that it is their priority but in reality, it is not the case. They should allocate resources to the lower levels and monitor for accountability at all levels. This is the way we should go.” (CSO official)

It was also noted that SRHR services are often lumped together as one set of services to be provided without due regard to gender differences and different age groups and their needs. There was therefore a strong advocacy against the wholesale programming and implementation of programmes and a call for priority setting that will give priority to populations with the greatest needs and interventions that will generate the desired results.

“I think we must look at the gender issues especially age groups. We have put everything together and we are not addressing the issues because there are different needs and a lot of people are left out. This is where we have a problem. It should be approached at different levels bearing in mind the needs of the different groups rather than just telling them that this is what we have to offer you.” (CSO official)

One other barrier that is affecting the implementation of SRHR programmes is the lack of integration of an effective referral system into them, particularly at the community level. The CHPS system was designed to bring health care closer to the people at community level but does not have the capacity to deal with complications relative to pregnancy or childbirth, which often require referral to the next level of health care. It was argued that the National Ambulance Service – which is supposed to bridge that gap – is under-resourced to be able to carry out such functions, to the extent that clients have to co-fund by way of paying for the cost of fuel etc.

“ … women are suffering and mortality was too high and if we have to reduce it drastically, we have to remove the financial and geographic barriers. So now we have the CHPS bringing health closer to where the people are but I can’t say that the CHPS can address everything. It is just the free services and then improving the referral system because sometimes when there are complications, the CHPS level cannot address the complications of pregnancy and childbirth. At best, the health worker there can recognize that but we need a good referral system so that the women can get to bigger facilities where there is medical care. So the referral system is something that I think should go under the health benefit package.” (Program Officer, Ghana Health Service)

“Process” challenges

The process factors impeding the implementation of reproductive health and rights programmes relate to the quality of services, because of ineffective monitoring and supervision and inequitable distribution of logistics and equipment for providing SRH services.

“ … we have to admit, sometimes, not the right people do the supervision and the monitoring, especially at the service level, you need hands on somebody to guide, so if the people who come to supervise you are even less knowledgeable about what you do, how do they guide you?” (Former Director, Ghana Health Service 2)

Some respondents argued that there has been good coverage for maternal and child health services, yet this is not reflected in the expected health outcomes. They lamented the fact that people continue to present adverse maternal health conditions amid good ANC coverage, which in their estimation is attributable to the quality of services. They maintain that the reason for monitoring and supervision is to offer guidance for effective service delivery; however, these activities are often carried out by persons who may not have expert knowledge in the area of SRHR and therefore may not be able to lend that expert guidance for effective implementation of SRHR programmes. Another issue was the lack of vehicles for carrying out monitoring and supervision activities.

Furthermore, there is a concern about equitable process in distributing logistics and equipment and trained health personnel to health facilities. It was said that more logistics/equipment often end up in places whose leaders are influential instead of going to places where they are more needed. There was also the view that most health sector resources are overconcentrated in the national capital and a few towns instead of going to communities where they are more needed, affecting effective implementation of reproductive health services including abortion services.

“There are sometimes challenges with having adequate personnel, equipment and commodities to implement services. So much as we desire to have the national level scale up, these barriers impede performance.” (Development Partner 1)

“ … And the other aspect of quality is availability of logistics and equipment, there have been efforts in this direction but there is still a big gap … At a point some districts don’t even have one vehicle for monitoring and supervision. So how do they go and see what is happening on the ground?” (Former Director, Ghana Health Service 2)

“ … Currently with all the CHPS zones spread across the country, only 15% of CHPS compounds have midwives. … although we have community health nurses going round doing the work but not all places that we have community health nurse who have midwifery background to address maternal and child health issues.” (NGO in Health)

It was also observed that some vulnerable groups of persons have difficulty accessing SRHR services.Citation37–39 For instance, women with disabilities are said to experience compounded vulnerabilities, including higher rates of violence, and lower rates of access to economic and social services, due to the fact that women with disabilities rank lower in every economic and social service indicator compared with their male counterparts.Citation40 This was confirmed in the qualitative analysis where disabled and older persons and adolescents were said to shy away from accessing SRH services in some instances. There was also the problem of geographical location which makes it difficult for SRH services to reach some people in inaccessible areas.

“We have gender issues, I mean men and women not getting access to quality health and a whole lot. We also have issues of resources, poverty level, geographical location are all part of the problem.” (CSO official)

“You know it includes both men and women and everybody. It involves gender issues and we have a lot of people who don’t have access to family planning. We have issues about young people who don’t have access to condom based on educational policies and so certain ages you can’t use condom and even in the schools you cannot promote its usage. And access to comprehensive abortion is not everywhere you can promote it, for example in the Catholic health facilities, you cannot promote it. And so those are the things. ” (CSO official)

Another challenge confronting SRH service provision is the inadequate coordination among NGOs/CSOs and other agencies involved in SRHR programmes. There was the notion that the GHS, which is the main health sector organisation responsible for implementing health programmes, does not rally together all organisations involved in SRHR to implement a comprehensive national SRHR programme that takes into consideration the gaps within the sector. In addition to the lack of coordination, there is also the issue of delays in the reimbursement of funds to service providers by the NHIS which is seriously affecting service delivery, especially SRH services covered under the benefit package.

“You see if the Ghana health service would want the civil service around, they should look at the civil society that is implementing SRHR and bring them together. There are a number of NGOs who have their own funding doing a lot of work. Alliance for reproductive health, hope for future etc. there are quite strong NGOs but unfortunately they are not part of any of their processes. So they should look at which NGO they should bring on board to support. We are not saying that they should give us money. We look for our own money and so whatever resources that they will get, we can track and add it to the work that we do and discuss with them the areas we want them to focus on and so when you are looking for resources, please fill those gaps for us. I think those are the things they should be doing. But if no engagement is being done and everybody is doing their own things, I think that is where I have an issue with. The coordination aspect is very weak. Who is coordinating NGOs in SRH? Nobody.” (CSO official)

“I think it is about access. Our national health insurance has issues. People provide services and do not get back their monies so there is a lot of back log of payment to service providers. These issues are very paramount in the private sector.” (CSO official)

Discussion

Health, including SRHR, is a constitutional right in Ghana;Citation41 however, numerous practical challenges have made it difficult for most Ghanaians to exercise their full right to SRH. These challenges range from health systems problems including inadequate and poor distribution of health workforce and logistics, leadership and governance challenges at the various levels of the health system; financial problems including late reimbursement by NHIS to service providers and low allocation of funds to the health sector; poor data quality; poor health infrastructure; and geographical accessibility challenges, as well as fragmented policies and programmes for integrating SRHR in the country.

In Ghana, various stakeholders are involved in the implementation of SRHR programmes. The majority of stakeholders outside the government sector provide mainly financial and logistical resources for implementation.Citation42 The Ministry of Health through its agencies and the Ghana Health Service implements SRHR programmes, including maternal and child healthcare services, abortion services and some aspects of GBV related services. Among the key SRH services, maternal and child health has always received priority in the national agenda and found its way into almost all programmes of work within the health sector.Citation42 Other SRH services including family planning services have been subsidised by donor partners but have not been integrated within the health benefits package of the NHIS due to resource constraints and partly also to low prioritisation. A cross-section of stakeholders have ensured that stringent measures are put in place to curtail expanding the benefits package to include the wide range of SRHR issues, as they fear this may potentially pave the way for the donor community to incorporate LGBT issues in the priority-setting for SRHR in Ghana.

Planning for health activities including SRHR programmes is primarily done by the Ministry of Health working together with its agencies. Decisions regarding costing, budgeting and human resource allocation go through both bottom-up and top-down approaches. District Health Management Teams (DHMTs) plan health activities including SRHR. These are collated at the regional level and inputted into national priorities and plans as well as the national Programme of Work. However it is important to note that studies have shown that financial allocations made by the Ministry of Finance often fall short of the budgets presented by the MoH and its agencies.Citation35 This makes implementation of health programmes, including reproductive health and rights programmes, difficult and creates a cycle of planning and less implementation of planned activities.

In Ghana, SRH services including maternal and child health, abortion/post-abortion care and some aspects of domestic violence support are largely integrated within routine health care delivery in health facilities. Family planning (FP) commodities are currently not reimbursed under NHIS but the commodities are highly subsidised by government and Development Partners. There are decisions/plans to incorporate clinical FP services into the NHIS benefit package. Marie Stopes International, NHIA and the GHS are piloting a system of reimbursement under the NHIS clinical FP services in some selected districts. However there are concerns that including FP services in the health benefits package will overstretch the “pot” as the NHIS is already facing challenges in reimbursement for services and is always late in reimbursing service providers.Citation43

Currently, about 8% of the national budget is allocated to health. However, most of that funding is being channelled towards worker remuneration, with little left to invest in improving healthcare services.Citation7,Citation22 Additionally, it is not known how much of the health budget goes to SRH.Citation7 In 2019, for instance, 99.8% of the Government budget for the Ghana Health Service was for salaries and emoluments of staff with almost nothing left for goods and services.Citation22 Thus the financial challenges for SRHR programme integration are actually part of broader financial resource challenges within Ghana’s health system.

Occasional shortages of essential supplies, including stock-outs of child health record booklets and maternal health record booklets, vaccines and basic commodities at health facilities, are prevalent in the country. Inadequate scanning machines at peripheral facilities make service delivery difficult, especially in instances where women have to be referred over long distances to conduct scans for their pregnancies. Adolescents can access SRH counselling services free through the Adolescent Corner, but the unfriendly location of these counselling centres (obscure areas at public health centres) is a challenge and the adolescents have to pay for commodities. Thus, there is inadequate access to adolescent and youth-friendly health services in the country.Citation27 Unfortunately 14% of adolescents aged 15–19 years have already begun childbearing.Citation15

In addition, socio-cultural and religious factors have hindered the delivery and use of some SRH services and issues of sexuality are not discussed openly, especially with young people, as most Ghanaian societies frown upon this. Male partners enjoy dominion over their female partners in most settings in Ghana, to the extent that they can take decisions that affect women’s use of family planning services. These challenges are compounded by poor enforcement of laws and policies on SRHR.

The community-based health planning and services programme is the lowest level of care in Ghana and currently has the highest number of service points in the country.Citation44,Citation45 However, many of the CHPS facilities do not have midwives to take care of deliveries and so mothers in rural areas often have to be transported on motorbikes for several kilometres on bad roads, which is contributing to the high maternal and child mortality in the country.

In spite of this, Ghana has made significant strides in the implementation of maternal and child health, safe abortion and GBV services through legislation and the establishment of a legal framework to ensure that these services are made available, accessible and acceptable to those who need them and that the requisite punishment is meted out to perpetrators of GBV. Unfortunately, socio-cultural and religious factors and myths surrounding such practices and enforcement of these pieces of legislation present obstacles, and financial allocations to address these are lacking. Advocacy is needed to improve financial allocations for GBV support programmes as well as tackling the socio-cultural and religious factors affecting implementation of these services. There is also a need for more education for women to be more assertive in demanding their sexual and reproductive health and rights, including the right to safe abortion and post-abortion care services.

To improve SRHR in Ghana, the health benefits package needs to be extended to cover more SRH services. Finding additional sources of financing for the NHIS can make this a reality. There is also the need for intersectoral collaboration and the development of a national master plan/strategy for SRHR integration. Standards and protocols for the implementation of SRHR interventions and effective monitoring and supervision are needed, as well as adopting community participatory approaches, such as involving stakeholders such as community champions or gatekeepers, queen mothers and peer educators and working with law enforcement agencies such as the police and lawyers. The media are also needed to help demystify negative socio-cultural and religious practices in order to ensure maximum results for SRHR interventions.

Study limitations

One of the main limitations of this study is the small sample size of the interviewees. In addition, participants in the in-depth interviews were selected using a non-randomised convenience approach based on authors’ knowledge of the involvement of their institutions in SRHR issues in Ghana. While the researchers made efforts to include as many key stakeholders involved in SRHR in Ghana as possible, the use of a convenience sampling coupled with the small sample size has implications on the generalisability of findings. A further limitation is the inability to quantify the magnitude of issues discussed, which is an inherent attribute of qualitative research. Lastly, due to time and resource constraints, lay community members were not included in the interviews. While stakeholders involved in SRHR programme planning and implementation are also community members and their views might align with community perspectives, we acknowledge this as a limitation as the views of lay community members could have brought into focus other issues not known to stakeholders involved in policy and implementation of SRHR. These issues notwithstanding, the triangulation of interview results with document review has largely improved the validity and reliability of findings in this study.

Conclusion

This study provides an understanding of the challenges and facilitators confronting the effective implementation of sexual and reproductive health and rights programmes in Ghana. It was found that there exists substantial integration of SRHR services within UHC initiatives in Ghana. However, several “structural” and “process” challenges limit Ghana’s efforts to expand population coverage, service coverage and financial protection for accessing essential SRHR services. Based on the results of this study, we propose the development of a national intersectoral master plan for SRHR programming in Ghana. Addressing the financial, logistical and health workforce inadequacies and maldistribution will go a long way to propel Ghana’s efforts in improving access to essential SRHR services. Ghana cannot achieve universal health coverage and the health-related Sustainable Development Goals if SRHR issues are not fully and adequately integrated into the NHIS (Financing) and the CHPS (service delivery) which are Ghana’s pathways for achieving universal health coverage.

Acknowledgements

JA, AK, EWK and DA conceived and designed the study with inputs from VG and GD. JA, AK, EWK and DA carried out analysis, interpretation of data and drafted the article. VG and GD critically reviewed the article. All authors read and approved the final version for submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Glasier A, Gülmezoglu AM, Schmid GP, et al. Sexual and reproductive health: a matter of life and death. Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1595–1607. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69478-6

- World Health Organization. Family planning/contraception; 2018. [cited 2020 April 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/family-planning-contraception

- United Nations. One-in-four pregnancies unplanned, two-thirds of women foregoing contraceptives; 2019. [cited 2020 April 22]. Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/10/1050021

- World Health Organization. Maternal mortality; 2019. [cited 2020 April 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

- World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs); 2019. [cited 2020 April 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis)

- World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation; 2020. [cited 2020 April 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation

- Esenam Amuzu. Sustainable financing for family planning; 2019. [cited 2019 October 11]. Available from: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/funding-family-planning-sexual-reproductive-health-services-trump-gag-rule-by-esenam-amuzu-2019-09

- United Nations. Transforming the world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development; 2016.

- United Nations General Assembly. Sustainable development goals: transforming our world; 2015. [cited 2019 October 3]. Available from: http://www.igbp.net/download/18.62dc35801456272b46d51/1399290813740/NL82-SDGs.pdf

- World Health Organization. Thirteenth general programme of work 2019–2023; 2019. [cited 2019 October 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/about/what-we-do/thirteenth-general-programme-of-work-2019-2023

- United Nations. International conference on population and development programme of action. UNFPA; 1994. [cited 2020 April 1]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/international-conference-population-and-development-programme-action#

- Ghana Ministry of Health. Ghana family planning costed implementation plan Government of Ghana Ministry of Health; 2015. Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/sites/default/files/Ghana-Family-Planning-CIP-2016-2020.pdf

- Boateng JA. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in Ghana: the role of parliament – social protection and human rights; 2017. [cited 2020 February 1]. Available from: https://socialprotection-humanrights.org/expertcom/sexual-reproductive-health-rights-ghana-role-parliament/

- Ghana Health Service. National reproductive health and service policy and standards; 2014.

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana maternal health survey 2017. Accra; 2018. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR340/FR340.pdf

- Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? J Am Med Assoc. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. DOI:10.1001/jama.260.12.1743

- World Health Organization. WHO | health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. World Health Organization. [cited 2019 May 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/whr/2010/en/

- Ghana Health Service. Ghana health service 2016 annual report; 2017.

- Ghana Statistical Service. Population projection of Ghana; 2019. [cited 2020 April 10]. Available from: http://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS); Ghana Health Service (GHS); ICF International. Ghana demographic and health survey 2014; 2015.

- Asamoah BO, Moussa KM, Stafström M, et al. Distribution of causes of maternal mortality among different socio-demographic groups in Ghana; a descriptive study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:159. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-11-159

- UNICEF. Health budget brief Ghana; 2019. Available from: http://apps.who.int/nha/database/ViewData/

- Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs. 1997;26(3):623–630. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x

- Casey D, Murphy K. Issues in using methodological triangulation in research. Nurse Res. 2009;16(4):40–55. DOI:10.7748/nr2009.07.16.4.40.c7160

- Bekhet AK, Zauszniewski JA. Methodological triangulation: an approach to understanding data. Vol. 20; 2012. [cited 2020 August 9]. Available from: https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1395&context=nursing_fac

- Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, Dicenso A, et al. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545–547. DOI:10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Ghana Health Service. Family health division, 2016 annual report; 2016.

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana multiple indicator cluster survey 2017/2018; 2019. Available from: doi:https://www.unicef.org/ghana/media/576/file/Ghana%20Multiple%20Cluster%20Indicator%20Survey.pdf

- Nyonator F, Ofosu A, Segbafah M, et al. Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in Ghana. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001691. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001691

- World Health Organization. Quality of care network – resources and data related to maternal, newborn and child health quality of care measurement. [cited 2020 September 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent/quality-of-care

- Awoonor-Williams JK, Tindana P, Dalinjong PA, et al. Does the operations of the national health insurance scheme (NHIS) in Ghana align with the goals of primary health care? Perspectives of key stakeholders in Northern Ghana. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16:21. DOI:10.1186/s12914-016-0096-9

- UNHCR. Ghana: domestic violence, including legislation, state protection and support services (2011–2015); 2015. [cited 2020 June 15]. Available from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/560b95c54.html

- Ghana Health Service. Ghana health 2018 annual report; 2019.

- Ghana Ministry of Health. National community-based health planning and service policy.

- Abekah-Nkrumah G, Dinklo T, Abor J. Financing the health sector in Ghana: a review of the budgetary process. Eur J Econ Financ Adm Sci. 2009;17:45–59.

- Takyi BK. Religion and women’s health in Ghana: insights into HIV/AIDs preventive and protective behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(6):1221–1234. DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00122-3

- Akazili J, Chatio S, Ataguba JEO, et al. Informal workers’ access to health care services: findings from a qualitative study in the Kassena-Nankana districts of Northern Ghana. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1). DOI:10.1186/s12914-018-0159-1

- Yiran G-SA, Teye JK, Yiran GAB. Accessibility and utilisation of maternal health services by migrant female head porters in Accra. J Int Migr Integr. 2015;16(4):929–945. DOI:10.1007/s12134-014-0372-2

- Lattof SR. Health insurance and care-seeking behaviours of female migrants in Accra, Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(4):505–515. DOI:10.1093/heapol/czy012

- Badu E, Gyamfi N, Opoku MP, et al. Enablers and barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services among visually impaired women in the Ashanti and Brong Ahafo regions of Ghana. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26(54):51–60. DOI:10.1080/09688080.2018.1538849

- Government of Ghana. The constitution of the Republic of Ghana; 1992. [cited 2019 April 29]. Available from: https://www.judicial.gov.gh/index.php/preamble

- Koduah A, Agyepong IA, van Dijk H. ‘The one with the purse makes policy’: power, problem definition, framing and maternal health policies and programmes evolution in national level institutionalised policy making processes in Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2016;167:79–87. DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.051

- Agyepong IA, Abankwah DNY, Abroso A, et al. The “universal” in UHC and Ghana’s national health insurance scheme: policy and implementation challenges and dilemmas of a lower middle income country. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):504. DOI:10.1186/s12913-016-1758-y

- Kanmiki EW, Akazili J, Bawah AA, et al. Cost of implementing a community-based primary health care strengthening program : the case of the Ghana essential health interventions program in northern Ghana. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):1–15.

- Ghana Health Service. National community-based health planning and services policy: accelerating attainment of universal health coverage and bridging the access equity gap. Accra, Ghana; 2016.