Abstract

This paper explores the universal health coverage (UHC) roll-out process in Kenya through the lens of its potential to progressively realise the constitutional promise of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in Kenya. We argue that SRHR requires significant attention to be paid to preventive and promotive approaches to health and that this requires interrogation of barriers around access to information, norms, and legal and policy frameworks. We then unpack the UHC process in Kenya, its genesis, development and eventual roll-out, focusing on the essential benefits package and its components. We argue that a process of democratic priority-setting cognisant of equity, non-discrimination and transparency will better deliver on an essential benefits package for access to SRHR that is legitimate and acceptable. As a result, we submit that Kenya’s UHC process fails to take cognisance of the weight placed on sexual and reproductive health in our Constitution and fails to address historical inequities around accessing health services.

Résumé

Cet article s’intéresse au déploiement de la couverture santé universelle (CSU) au Kenya dans l’optique de son potentiel pour réaliser progressivement la promesse constitutionnelle de la santé et des droits sexuels et reproductifs dans le pays. Nous faisons valoir que la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs exigent d’accorder une attention considérable aux approches de prévention et de promotion de la santé, ce qui nécessite de s’interroger sur les obstacles autour de l’accès à l’information, des normes et des cadres juridiques et politiques. Nous exposons ensuite le processus de la CSU au Kenya, sa genèse, son développement et son déploiement ultérieur, en nous concentrant sur le panier de services essentiels et ses composants. Nous affirmons qu’un processus démocratique de définition des priorités, respectueux de l’équité, de la non-discrimination et de la transparence, sera plus à même de parvenir à mettre en œuvre un panier de services essentiels pour l’accès à la santé et aux droits sexuels et reproductifs qui soit légitime et acceptable. Par conséquent, nous avançons que le processus de la CSU au Kenya ne reconnaît pas le poids accordé à la santé sexuelle et reproductive dans notre Constitution et ne réussit pas à corriger les inégalités historiques autour de l’accès aux services de santé.

Resumen

Este artículo explora el proceso de implementación de cobertura universal de salud (CUS) en Kenia desde la perspectiva de su potencial para realizar progresivamente la promesa constitucional de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SDSR) en Kenia. Argumentamos que SDSR requiere que se preste atención significativa a los enfoques preventivos y promotores de salud, para lo cual es necesario interrogar las barreras en torno al acceso a información, normas y marcos legislativos y normativos. Luego desentrañamos el proceso de CUS en Kenia, su génesis, su desarrollo y finalmente su implementación, enfocándonos en el paquete de beneficios esenciales y sus componentes. Argumentamos que el proceso de establecer prioridades democráticas conscientes de la equidad, no discriminación y transparencia podrá cumplir mejor con la entrega del paquete de beneficios esenciales para el acceso a SDSR que sea legítimo y aceptable. Por consiguiente, consideramos que el proceso de CUS de Kenia no reconoce la importancia atribuida a la salud sexual y reproductiva en nuestra Constitución y no aborda las inequidades históricas relacionadas con el acceso a servicios de salud.

Introduction

Kenya has enshrined the right to health in Article 43(1) (a) of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010, which provides that: “Every person has the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to healthcare services, including reproductive health”. The Constitution nuances reproductive health and rights in a number of provisions including guaranteeing the right to non-discrimination on the basis of pregnancy and liberalising access to safe abortion by expanding the grounds (Articles 26[4] and 27[4]).Citation1 This emphasis was not a coincidence but a deliberate attempt to address marginalisation and neglect of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in Kenya. Therefore, the move towards universal health coverage (UHC) as a tool towards the progressive realisation of the right to health has been met with optimism, albeit cautiously. This paper explores UHC in Kenya and its ability to meet the constitutional promise around SRHR and provides a critique on the shortcomings of the UHC process that may ultimately result in a failure to realise Article 43(1) (a) of the Constitution within the lens of sexual and reproductive health (SRH).

Methodology

This study relied on qualitative analysis of secondary data on the implementation of UHC obtained from county and national government bodies, including the Ministry of Health (MOH), National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kenya Medical Association and the National Treasury. Documentation data from these sources included cabinet memoranda, meeting documentation county government reports and policy briefs. Information was also drawn from reports developed by various stakeholders such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank; academic sources on the implementation of UHC in Kenya; and news sources. Kisumu County (one of the four pilot counties) was used as a case study. Kisumu was chosen as the case study because the authors have first-hand experience of engagement in the roll-out process as have significant contextual knowledge of that county.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights

SRHR: a definition

Reproductive rights were first touted in the international sphere as a subset of human rights in the 1968 Proclamation of Tehran. The proclamation gave parents the human right to freely determine the number and spacing of their children.Citation2 This right was affirmed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1969, terming it a “parent’s exclusive right”.Citation3

The catalysts for the movement to recognise reproductive rights as human rights were the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) held in Cairo in 1994, and the Fourth World United Nation Conference on Women held in Beijing the following year.Citation4 ICPD reflected the notion that reproductive rights encompass existing human rights and tendered a definition of reproductive health:

“Reproductive health is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes … reproductive rights embrace certain human rights that are already recognised in national laws, international human rights documents and other consensus documents. These rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. It also includes their right to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence, as expressed in human rights documents.”Citation5

Reproductive health therefore implies that people are able to have a safe and satisfying sex life have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to make decisions regarding their reproductive health. Sexual health is defined by WHO as “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality”.Citation6 This requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as safe and pleasurable sexual relationships.

Legal and policy framework on SRHR

Kenya has a robust framework of laws and policies that relate to SRHR, from the Constitution to health policies and strategic frameworks. Moreover, Kenya is a State Party to various international and regional instruments that guarantee SRHR.

Internationally, health is recognised as a fundamental human right that is indispensable to the exercise of other human rights and includes the right to maternal, child and reproductive health; and the right to prevention, treatment and control of diseases that adversely affect SRH.Citation7 The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has affirmed that sexual and reproductive rights are an integral part of the right to health and States are required to take steps to the maximum of available resources to make such services available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality.Citation8

The African regional human rights framework explicitly recognises the reproductive health and rights of women. Duties are placed on the State to ensure that SRHR are respected and promoted. Specific rights elucidated include the right to: control their fertility, family planning education, make decisions on whether to have children, the number and the spacing of children, choose methods of contraception and be protected against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV. States are also required to provide reproductive health services, including education; and medical abortion in cases of sexual violence including assault, rape and incest, and where the life and/or physical and mental health of the pregnant woman is in danger.Citation9

The Kenyan constitution recognises the right to health including the right to the highest attainable standard of reproductive health. Women and girls are also accorded the right to a safe abortion where, in the opinion of a trained medical provider, the life or health of the pregnant woman is in danger.Citation1 The High Court of Kenya has interpreted this provision to mean that women and girls have a right to abortion in exceptional circumstances including where there is need for emergency medical treatment, where the physical, mental, psychological, and social health and well-being of the pregnant woman is in danger. The Court utilised the provision on “any other law” finding that the Sexual Offences Act, 2006 qualified under these circumstances and provided for access to safe abortions in the instance of sexual violence.Citation10

The right to reproductive health includes the rights to access and be informed about safe, effective, affordable and acceptable family planning services; appropriate healthcare services that enable parents to safely go through pregnancy, childbirth and the post-partum period; and treatment by a trained health professional for conditions occurring during pregnancy, including any medical condition exacerbated by the pregnancy to the extent that the life or health of the pregnant woman is threatened. It is the State’s fundamental duty to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the right to the highest attainable standard of reproductive health care by ensuring the provision of a health service package at all levels of the health care system. This package ought to include promotive, preventive, curative, palliative and rehabilitative services as well as physical and financial access to health care.Citation11

A comprehensive package for SRHR

Sexual and reproductive health care encompasses the whole life cycle of an individual from birth to old age and services must therefore be provided along the continuum of care. Comprehensive SRH care should include access to preventive, promotive, curative, palliative and rehabilitative SRH services that are rights-based and equitable in access.

Core elements of SRHR include maternal health and newborn care; safe abortion care; family planning; prevention and management of STIs including HIV and non-sexually transmitted reproductive tract infections (RTIs); prevention and management of infertility; prevention and management of cancers of the reproductive system; addressing mid-life concerns of men and women; health and development; reduction of gender-based violence; interpersonal communication and counselling; and health education (see ).Citation12 Adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) is also a component of SRHR and includes the elements of SRHR outlined above.Citation6 Adolescents require SRH services specifically geared towards them as they require different health, education and social services to meet their reproductive health needs.Citation13

Taking a preventive and promotive approach to SRHR

In order to meet sustainable development goals 3 and 5 on good health and well-being and gender equality, universal access to comprehensive SRH services is key. However, in resource-constrained environments, this is at best progressively realisable. Preventive and promotive approaches may be strategic to adopt as they tend to be cost-effective and even cost saving, and they lead to better health outcomes in the long term.Citation14 Preventive health services encompass actions aimed at avoiding the manifestation of disease through provision of information, vaccination and early detection of disease, thus improving the chances for positive health outcomes. Promotive services empower people to increase control over their health and its determinants through education and awareness efforts and action to increase healthy lifestyles and behaviour.Citation15

There is evidence of the efficacy of preventive and promotive approaches. Reproductive health services have continuously been strengthened across Kenya in connection with a gradual increase in the contraceptive prevalence rate among married women between 1978 and 2009. Other preventive and promotive strategies included making methods of modern contraception available and dissemination of family planning messages, while community involvement in advocacy and disseminating information led to increased access, availability and uptake of SRH services. This contributed to a drop in fertility rates from 5.4 in 1993 to 4.6 in 2003.Citation16

It is almost axiomatic that comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) has a positive impact on SRH, especially in reducing STIs, HIV and unintended pregnancy. It is vital as adolescence is a period of significant growth and development and is filled with vulnerabilities. It also presents a unique opportunity for fostering better health outcomes as adolescents’ experiences likely shape their health behaviour throughout their lives.Citation17 A United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation study on the cost-effectiveness of CSE found that CSE programmes are highly effective, cost-effective and may even be cost saving, especially if they are intra-curricular, nationally rolled out and jointly delivered with youth-friendly health services.Citation18 A 2014 study of school-based sexuality education programmes noted that there was a demonstrable increase in HIV knowledge, contraception and condom use, and a reduction in risky sexual behaviour among students.Citation19 The results of a pilot programme in Kenya noted that more than 6000 students who received sexuality education reported increased condom use among the sexually active, and delayed sexual initiation compared to more than 6000 students who did not receive such education.Citation20

The Guttmacher Institute estimates that if all unmet needs for modern contraception among adolescents in Kenya were satisfied, unintended pregnancies would drop by 73% from 218,000 per year to 58,000 per year, resulting in reductions in the annual numbers of unplanned births from 111,000 to 30,000 and abortions from 77,000 to 20,000. Adolescent maternal deaths would drop by 39% from 450 per year to 280 per year. If full provision of modern contraception were combined with adequate care for all pregnant adolescents and their newborns, adolescent maternal deaths would drop by 76%, from 450 per year to 110 per year.Citation21

HPV vaccines for pre-adolescent girls have been associated with a range of 28–49% reduction in the lifetime risk of contracting cervical cancer. Vaccines combined with screening showed a risk reduction of up to 56%.Citation22

A comparator is Uruguay’s SRHR package of care, that includes provision of low cost or free modern contraceptives, screening of reproductive health cancers, CSE, information and counselling, and has contributed to a reduction of the adolescent fertility rate from 57 per 1000 live births in 2015 to 36 per 1000 live births in 2018. Reportedly, 91.7% of women and 85.9% of men are regular users of modern contraceptive methods.Citation23

Evidently, access to SRHR and all that they entail is critical to ensuring that the right to the highest attainable standard of health is realised. In light of the global movement to ensure that all persons can receive essential health services without suffering financial hardship,Citation24 it is imperative that a comprehensive approach to SRHR is adopted to effectively meet people’s SRHR needs.

Universal health coverage

Framing universal health coverage

The right to the highest attainable standard of health is guaranteed in the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Article 16),Citation9 as well as other regional and international human rights instruments. In pursuance of the right to health, the 58th World Health Assembly urged member states to work towards guaranteeing universally accessible health care to their populace based on the principles of equity and solidarity.Citation25

UHC entails ensuring that all people obtain the health services they need without suffering financial hardship.Citation24 UHC encompasses all components of a health system. Achieving it necessitates investment in health service delivery systems, the health workforce, health facilities and communications networks, health technologies, information systems, quality assurance mechanisms, and governance and legislation.Citation24 The essence of UHC however, is that everyone should have access to the health services that they need without risking financial ruin.

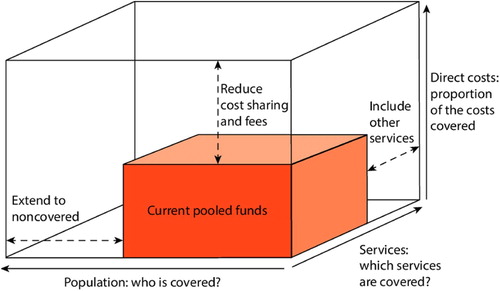

The path to UHC involves important policy decisions and inevitable trade-offs. Funds can be pooled from a variety of sources following a policy decision but once pooled, countries should work towards three dimensions: extending coverage to individuals not previously covered; expanding services and including services not previously covered; and finally reducing the direct cost of each service.Citation26 These dimensions are illustrated (see Figure 1).

While the illustration in seems simple, the process required to achieve it is anything but. Countries are faced with a series of difficult choices such as: which services to expand first? How to reduce costs? Which populations must be reached or prioritised? Which services must be prioritised? These are all difficult choices with necessary trade-offs but, significantly, the legitimacy of these decisions can be pegged onto the robustness of accountability and participation mechanisms that facilitate the process of decision-making.Citation27 Thus democratic priority-setting is not just a component of UHC, it is the process under which we can develop an equitable mechanism towards achieving UHC.

Democratic priority-setting

Priority-setting can be defined as

“the task of determining the priority to be assigned to a service, a service development or an individual patient at a given point in time. Prioritisation is needed because claims (whether needs or demands) on healthcare resources are greater than the resources available.”Citation28

In health systems, priority-setting is about allocation of resources to commodities, programmes, training of practitioners; about deciding which populations should access subsidised or even free care; and even about complex policy interventions. It is about making explicit decisions about what to fund and weighing various options, leading to tradeoffs in the process.Citation28

Priority-setting is a key component of UHC because states have to make difficult choices about what and how to finance health, and this is especially true for countries with limited resources.Citation29 This is a crucial process because decisions on how state resources should be utilised should be made in an equitable, non-discriminatory, transparent and accountable way. The health system is a part of democratic governance and therefore questions to be answered around priorities are not merely technical but require active participation of citizens in decisions regarding their health.Citation29

The WHO suggests a framework for priority-setting that countries can adopt. Countries begin by defining principles and scope of UHC and through this should stipulate guiding principles which, within a rights-based framework, must include human rights principles.Citation27 While setting principles is an important aspect of priority-setting it has been critiqued for being too general and unclear in practice.Citation30 Reaching consensus on principles is especially difficult in pluralist societies, such as Kenya, where there may be reasonable disagreements on guiding principles. In those instances, Daniels argues that in the absence of consensus on principles a fair process can lead to consensus on what is legitimate and fair.Citation30 On fair process we can learn from Mexico’s experience on priority-setting after an epidemiology shift seeking a democratic and participatory process noted that the process ought to be evidence-based, equitable, transparent, and contestable.Citation31

The second requirement by WHO is operationalising the principles, which seeks to put into place a process for priority-setting with a four-step protocol: (i) identifying interventions; (ii) finding evidence; (iii) taking decisions; and (iv) making appeals.Citation27 In Mexico, cost-effectiveness played a key role both in identifying interventions and in finding evidence. However, a key lesson was that international estimations may misguide national resource allocation decisions, while countries with less resources may lack extensive, reliable and valid data as well as technical analytical capacity to localise the cost-effectiveness discourse.Citation27 Therefore, for Mexico the availability of local epidemiological information (to identify the interventions) and economic assessment helped unearth what would not be transferable from international estimations.Citation30 Another lesson from Mexico in this process was the inclusion of non-health considerations in priority-setting; systems should seek to reduce inequality in distribution of health gains and in levels of responsiveness across population groups.Citation30 This will include non-technical concerns such as criminalisation of certain populations; or social constructs that limit use for others. To address this, priority-setting resulted in two groups being engaged: the first to discuss analytical criteria subject to quantification, such as costs, budgets and implementation constraints. The second focused more on qualitative concerns through a deliberative process by different stakeholders.Citation30

Finally, once priority issues have been selected and a decision taken and implemented, the WHO recommends a process of monitoring and evaluation to assess the priority-setting process, learn from it and possibly improve upon it in a second iteration.Citation30

While priority-setting is a component of UHC, it is a key component of every health system given that there are always more needs than there are resources, and deciding what to fund and when is a constant question. What democratic priority-setting seeks to do is to create a publicly acceptable process for taking decisions. Key elements will include: transparency, appeals to acceptable rationales, and procedures for challenging decisions.Citation32 When priority-setting does not take place explicitly or informed by an agreed process it still takes place implicitly and often lacks legitimacy.

UHC in Kenya

At least half of the world’s population lack full healthcare coverage for basic health services; more than 800 million people spend 10% of their family budget on health services; and nearly 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty due to the cost of health services.Citation33 As of 2014, 48% of Kenyans did not have essential healthcare services and were susceptible to financial hardship due to health costs.Citation34

In a bid towards the progressive realisation of the right to the highest attainable standard of health, the implementation of UHC targets attaining 100% health coverage for all Kenyans.Citation35 The right to health intersects with other rights enshrined in the Constitution including the rights to life, equality and non-discrimination, human dignity, privacy and access to information.Citation36 The State is required to take all legislative, policy and other measures to achieve progressive realisation of the right to health (Article 21).Citation1 Such measures include ensuring prioritisation and adequate investment in research for health; ensuring realisation of the right to heath of vulnerable groups within society; and providing a health service package at all levels of the health care system.Citation11

The implementation of UHC will require reforms in all aspects of the health system as the architecture of health financing plays a central role in the larger health system. This means that all NHIF schemes, MOH programmes and social protection programmes by the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection must be restructured in order for it to be aligned. Legal reform of relevant instruments such as the NHIF Act, the Insurance Act, the Health Act and other relevant regulations is required to mandate NHIF to develop new structures that will ensure quality, equitable and efficient health care at all levels.Citation35

Afya Care – the Kenyan context

Kenya’s UHC pilot or “Afya Care” is not synonymous with universal health care, as the latter implies that there is provision of all health services. Rather, Afya Care implies that all Kenyans will be covered under a minimum package of primary health care.Citation37 Afya Care aims to ensure realisation of the right to health without financial hardship on the citizenry. Therefore, it must be prioritised, reflected within the national budget allocation and there must be significant political goodwill to ensure its realisation.Citation38

Historically, the Kenyan government has underfunded the health sector and has been reliant on donor funds and out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure.Citation34 OOP is the highest contributor of the largest share of total health expenditure as the Kenyan government has continually allocated less than the 15% required by the 2001 Abuja Declaration on Roll Back Malaria in Africa.Citation34 The current government’s spending priorities for the FY2019/2020, amounting to Ksh. 2.8 trillion, are in four broad areas, one of which is implementating UHC.Citation39 Of the Ksh. 2.8 trillion, Ksh. 47.8 billion has been allocated to UHC roll-out, including scaling up to other counties (the pilot phase included four of Kenya’s 47 counties) and improving the NHIF to adequately care for the vulnerable, such as the elderly and disabled.Citation39

UHC’s strategic outcomes are: 100% access to essential health packages and medicines by 2022; a reduction in OOP expenditure from 32% to 20%; accelerated progress towards achieving the optimum ratio of 23 healthcare workers per 10,000 (currently at 10–13 per 10,000); increased population access to health facilities within a 5 km radius from 91% to 100%; increased community units from 55% to 100% by 2022; and a reduction in infant mortality from 16 to 4 per 1000 live births.Citation40 Additionally, the government aims to achieve UHC through reforms in governance of private insurance companies; restructuring NHIF including expanding its coverage and benefits;Citation41 scaling up the support of plans geared towards the provision of specialised medical equipment; increasing the total number of health facilities; scaling up the Linda Mama programme; and strengthening health research.Citation42

UHC pilot phase

Kenya’s aspirations for UHC are derived from the Development Blueprint of Kenya Vision 2030.Citation34 The UHC pilot phase was rolled out in 2018 in Nyeri, Isiolo, Kisumu and Machakos counties with the aim of providing medication and medical equipment, improving the infrastructure of hospitals and addressing human resource concerns.Citation43 These counties were chosen for their high maternal mortality rates, road traffic injuries, and high levels of communicable and non-communicable diseases.Citation43 Running for a period of 12 months, the intention of the pilot phase was to draw out best practices before scaling up nationally.Citation38

In the pilot phase, the approach to UHC focused on the scrapping of user fees at public health facilities at all levels and securing commodities through the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA).Citation44 Additionally, the MOH provided conditional grants to the four pilot phase counties in an effort to strengthen their primary health care interventions.Citation45 The pilot phase scaled up the use of Community Health Volunteers (CHVs); investment in standardising diagnostics; prioritising the National Integrated Identity Management System for biometric registration; and monitoring and accountability systems. Structural reforms to NHIF focused on efficiency, financial sustainability and transparency to ensure that all Kenyans may enjoy health services without the financial risk.Citation46 Finally, the UHC pilot phase had a focus on primary health care including immunisation facilities, maternal and child health services, HIV, TB and sexually transmitted infections, and a focus on nutrition for women and children for the first five years of life.Citation46

Financing mechanism

The government acknowledged that UHC can only be achieved through increasing public expenditure on health. As such, it allocated revenue specifically directed towards paying insurance subsidies for NHIF premiums meant to cover the economically marginalised. NHIF currently covers 15% of the Kenyan population, which translates to 88.4% of Kenyans with health insurance. Contribution is compulsory for all formal sector workers and voluntary for informal sector workers.Citation35 Although there have been measures to increase the financial capacity of NHIF by increasing the amount that workers pay and introducing outpatient cover,Citation47 there have been systematic shortcomings in the use of NHIF as an efficient vehicle to deliver UHC. Currently, the regulatory and policy framework to guide purchasingCitation48 between NHIF and MOH is weak. Additionally, monitoring and accountability is weak and majorly focused on financial practices. The need to determine NHIF reforms and an essential benefits package which promotes the sustainability of NHIF while improving strategic purchasing remains a priority of the NHIF reforms task force.Citation49 The MOH announced that KEMSA would be the main provider for health commodities while NHIF would continue to be the main purchaser of UHC.Citation50

The health benefits package

The Health Benefits Package provides an outline as to what efforts have been undertaken in the process of defining an essential services package and the criteria upon which it should be based. As UHC is a health financing system, rather than the construction of an entirely new health benefits package, the UHC health benefits package is to be developed from existing mechanismsCitation51 such as the NHIF health benefits package, and the KEHP (Kenya Essential Package for Health),Citation52 and from KEMSA for its provision of medical equipment.

The UHC health package is yet to be defined, thus the current health package implemented is the voluntary NHIF package (see ). The NHIF’s national scheme is targeted towards formal and informal sector workers, self-employed persons and includes declared spouses and children; Linda Mama which covers all pregnant women who are citizens of Kenya; the Health Insurance Subsidy for the Poor scheme which covers orphans and vulnerable children,Citation53 and Inua Jamii which aims to cover poor elderly persons and persons with disabilities.

Table 1. Core elements of sexual and reproductive healthcare services

Table 2. NHIF healthcare benefit package

At the time of the roll-out of the Afya Care pilot, the UHC package was yet to be defined and the information is not in the public domain. Thus far, the UHC package has been described more along the lines of its concept within various policy documents and development plans and has therefore resulted in the minimal articulation of what the UHC health package actually entails.Citation53

A UHC–Health Benefits Package Advisory Panel (UHC-HBAP)Citation56 was tasked to design the UHC–Essential Benefits Package (UHC-EBP), a responsive health benefits package for the delivery of UHC. UHC-HBAP set a standard criterion for assessing inclusion of services, drugs, medical supplies and technology that is essential to the realisation of the UHC-EBP and to ensure services are costed accurately through quality evidence that allows for the estimation of supply and demand.Citation57 UHC-HBAP weighed what the health system should do against what it can do.

UHC-HBAP adapted a modified nominal group technique to develop the following criteria: effectiveness and safety; feasibility of health workforce requirements; feasibility of health products and medical technology requirements; catastrophic health expenditure; burden of disease; affordability; cost-effectiveness; severity of disease; congruence with existing priorities; and equity in access to and use of services.Citation58 The panel ensured that these priorities were built on already existing mechanisms and responded to specific entitlements of Kenyans, while at the same time adhering to the standards of requirements for health service providers and being specific about the complementary role of insurance services.Citation58

UHC in Kisumu

In order to strengthen referral systems and scale up the use of healthcare workers in an effort to bridge human resource gaps, Kisumu County focused the implementation of UHC on a facility improvement programme at the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital.Citation59 During the pilot phase in Kisumu County, UHC involved training CHVs to facilitate promotive and preventive health care at the community level, with more comprehensive services being delivered at the level 2 and 3 facilities.Citation60 Kisumu County was allocated Ksh. 510 million for medical equipment, health products and technology.Citation61 The county received commodities worth Ksh. 217 million from KEMSA as of November 2019. As a result of these interventions, the county has registered 843,863 people for the UHC package.Citation62

The challenges faced by Kisumu County during the pilot roll-out of UHC included: congestion in level 4 and level 5 hospitals and the underutilisation of level 2 and 3 hospitals; human resources issues such as the overworking and underpayment of nurses; lack of efficient information systems; the interruption of the Linda Mama programme; and the overuse of the diagnostic radiology services.Citation59 The interruption of the Linda Mama programme was due to the delayed and low rate of the transfer of funds to public hospitals by NHIF.Citation32 At the launch of the pilot programme, Kisumu was to receive Ksh. 877 million in order to compensate for the scrapping of user fees, of which only half has been received. KEMSA has reportedly not supplied medical equipment and medication as mandated.Citation63

Successes, challenges and lessons learned

There has been a 30% increase in health services due to their financial accessibility; there has been an acceptable supply of pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical commodities by KEMSA as 99% of tracer medical supplies and 95% of tracer non-pharmaceutical supplies are now available at health facilities; and a dashboard to monitor real-time implementation of UHC is in the development process.Citation44 Reported successes also include an increase in access and use of health facilities which implies that marginalised groups not previously able to access healthcare services were able to do so during the pilot phase.Citation50

Despite the notable improvements, a number of challenges have been observed. Firstly, while user fees were scrapped in public health centres and dispensaries, OOP costs still exist in public and private healthcare centres,Citation34 which continues to be a key barrier to curtailing financial risk, while co-payments do not sufficiently reflect a patient’s financial capacity to afford payment.Citation63 Secondly, there is still a need to strengthen the capacity of health facilities and referral systems in raising awareness and sharing information with health service users,Citation44 as information such as the new premium contribution was not adequately communicated.Citation53 Additionally, there are also irrefutable disparities between urban and rural communities in accessing healthcare services such as family planning, vaccines and antenatal care that illustrates continued inequity. Further, there is low observance of clinical practice guidelines for management of maternal and neonatal care. Finally, there are deficits of medical commodities; lack of minimum medical equipment such as thermometers, scales and sterilization tools; and lack of adequate infrastructure such as water, sanitation and electricity.Citation64 The manner in which NHIF would work as a mechanism for health financing has proved complex and with these persistent gaps, the health benefits package remains inaccessible.Citation53

Other challenges to governance of UHC structures include the delay in the transfer of funds from national government to county governments. There are delays in reimbursement of funds used in delivering free maternity services.Citation32 Contributing to these delays is the process of transferring funds through the County Revenue Fund, as per the Public Financial Management Act.Citation63 For example, Ksh. 951 million from KEMSA allocated to pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical supplies which was to be released in July 2019 experienced several months delay.Citation64 Finally, there is need to strengthen the monitoring and evaluation health management system to both expand and improve quality of data collected and evidence-based service provision.

While Kisumu’s implementation of UHC did involve an aspect of preventive and promotive services, as reported by Kenya’s Cabinet Secretary for Health via the WHO during the launch of UHC in 2018,Citation60 the general allocation of funds was mainly focused on basic and specialised care (72%); while 12% of funds were allocated to community health services; 15% to health system strengthening; and 1% to public health services. The funds allocated to community health services were directed towards the training of Community Health Workers.Citation65 These figures demonstrate that the allocation of UHC funds in the pilot phase focused heavily on a curative approach. The MOH is currently focused on promotional and preventive measures to health care within the UHC package (prior to national roll-out) as a result of experiences from the pilot phase.Citation66

Priority-setting in Kenya

A study on priority-setting, undertaken across 10 counties with the lens of health equity and community-based primary care, underscored key concerns with priority-setting after the transfer of functions to county governments.Citation67 While most of the respondents in this qualitative study appreciated the need for devolution to decentralise decision-making for health, many recognised that decentralisation had not led to community involvement in decision-making. Key concerns include:

The process in how priorities are made and weighted against each other remains unclear.

There is limited technical community capacity for county priority-setting.

Mistrust between actors at both levels has resulted in the national government playing a limited role in providing guidance.

Barriers faced by marginalised groups in engaging in the process were not addressed or even considered.

Most counties within the study did not seek to improve understanding of citizens on health holistically and thus there was preference for curative aspects of health.

Most of the community engagement processes were donor-dependent and would be dropped once funding was unavailable.

In many instances the process was captured by a “political elite” and prioritisation reflected political and power interests, often favouring decisions around curative health that could gain political mileage.Citation67

The study found that while devolution addressed equity between counties, it has failed to address equity within counties and the gaps within the priority-setting process were illustrative of this.Citation67

The findings from the above study do not differ significantly from the roll-out of the UHC pilot phase and are demonstrative of the normative gaps between practice and the international framework on the right to health, as well as our own framework on participatory decision-making as captured in our national values (Article 10).Citation1 The lack of consultation was underscored from the onset in the choice of pilot counties, which were chosen for diverse reasons which were only communicated following the decision. What informed that decision was not clear; for instance, Kisumu County was chosen because of the high burden of communicable diseases, but neighbouring Homa Bay and Siaya Counties have similarly high burdens of communicable diseases. It is probable that other criteria informed the decision but such criteria were neither communicated, nor subjected to debate or engagement. The State failed in the first instance to engage in a democratic process of determining what would be an investment priority for Kenyans in a particular county.

Secondly, while UHC is a laudable aspiration and a tool for seeking to progressively realise the right to health in Kenya, it is a campaign promise. It is tied to Kenya’s vision 2030 but it was also a key component of President Uhuru’s manifesto in his re-election campaign. This is problematic for a number of reasons. Firstly, health is a devolved function. There already exists significant distrust between the national and county governments that resulted in a transfer of functions without transitional plans.Citation66 This paternalistic decision-making has been demonstrated by President Uhuru’s administration through the Linda Mama programme whereby the government committed to providing free maternal care without meaningful consultation with counties on how this would be operationalised and how funds would be transferred, leading to counties being unable to provide services that had been communicated to citizens as free.Citation68

Further, as a campaign promise this decision is now time-bound; this administration ought to fulfil it by 2022 and because of that, crucial steps have been skipped. Many documents provided by the State made reference to an essential healthcare service,Citation69 which remains unclear across the board and while the health benefits package provides set criteria that ought to be met, these were decided by an advisory panel. These criteria – which essentially form the principles for priority-setting – were reached without consensus and now guide the process of setting priorities.

This failure to meaningfully engage citizens was demonstrated at the Third UHC Conference held in Kisumu County on 15–17 May 2019. Following that conference, a Communique was published seeking to illustrate the diversity of voices in reaching consensus. However, the experience of stakeholders attending the conference was different, with the space being narrowed and only a few members of civil society being allowed to participate.Citation70

The Communique noted further flaws in the process, beginning with the need for a universal coverage policy. This was communicated five months after the process for registration for coverage had begun in Kisumu and citizens had been asked to be a part of it. It is unclear what had been guiding the registration, what citizens were registering for and what the implications of non-registration are in the absence of a policy framework.Citation71 Additionally, what citizens were entitled to as essential services or subsidised services was not communicated before or during the process of registration. Further, there is no evidence from the Communique to underscore or amplify the voices of marginalised groups, such as women, sex workers, adolescent girls and young women, or men who have sex with men. This notable exclusion raises concerns that the needs of these communities will not be prioritised and that seeking to address health equity may fall short as a result.

Democratic priority-setting is time-consuming, expensive and challenging, given the information asymmetries and diverse interests; however, it is necessary for accountability, transparency and legitimacy in decision making.Citation28 The Kenyan UHC experience has thus far mimicked our paternalistic past with decisions being taken at the top and communicated as a fait accompli. Our constitutional process was lengthy because it was a revision of a social contract that had bound us and failed to serve Kenyans for decades; we renegotiated this contract and our processes must mirror this renegotiation.

A critique of the essential benefits package for SRHR

SRHR may be systemically neglected in many essential benefits packages and three factors require attention to mitigate this: accessibility; legal and policy frameworks; and social norms.Citation72 Kenya still contains a number of barriers in the legal and policy framework that may limit the discourse around essential SRHR services, including: continued criminalisation of sexual minorities;Citation73,Citation74 restriction of access to safe and legal abortion;Citation10 and infantilisation of adolescents that bars them from seeking various SRHR services without parental consent. Additionally, cultural norms have an impact on realisation of SRHR and these have to be unpacked. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights repeatedly cited an insensitivity to cultural norms in service delivery and cultural acceptability of maternal services as barriers of access to care.Citation75

Kenya still suffers a number of barriers that may hinder meaningful discourse around priority-setting for SRHR. However, as a country we are in full swing in the implementation of UHC, seeking to scale up to the other 43 counties at the finalisation of the pilot. As authors we sit in a quagmire, we have made a case for preventive and promotive approaches to SRHR demonstrating their link to better health outcomes. We have placed these approaches within a policy framework that guarantees a rights-based approach to health. The quagmire we sit in is that we have little to critique. As noted above, the essential benefits package – though repeatedly referred to – remains undefined. We have principles and criteria to guide priority-setting and development of a package, but within the counties where UHC has been rolled out, there is no documentation that this package has been defined.

Frankly, Linda Mama, the free maternal care package that is – or at least ought to be – available nationwide is the only defined essential benefits package. This is a programme aimed at universal access to maternal and child health services. The package covers antenatal care, including preventive services such as malaria prophylaxis and prevention of mother to child transmission; delivery (access to a skilled birth attendant); post-natal care for six weeks after birth, focusing on the mother and child; as well as conditions and complications during pregnancy, including access to post-abortion care.Citation76

The Linda Mama programme ensured that there were no costs to giving birth.Citation77 The programme allocated Ksh 6000 per woman for normal delivery and Ksh 17,000 for Cesarean Section delivery. Between 2013–2016, the Linda Mama programme cost Ksh. 12 billion and benefited 2.3 million women.Citation62 In FY2016/2017, Ksh 6 billion had been allocated towards Linda Mama and has since almost halved to Ksh. 3.2 billion which is notably too low to carry out the programme effectively.

While arguably comprehensive, Linda Mama falls short of a comprehensive SRHR package as it only includes one component of SRHR, its goal of safe motherhood. Additionally, there are no promotive aspects within Linda Mama, which has resulted in many Kenyan women failing to understand the package and its benefits for them. Essentially, because of the continued failure to define an essential benefits package, the only package we can identify is one launched by the national government despite provision of health services being a county function. Because of this failure, emphasis for the realisation of SRHR remains largely curative. Preventive and promotive services are underutilised and this affects and will continue to affect people’s most intimate decisions about their SRH and in turn their right to dignity.Citation28 This approach has a gendered impact as it disproportionately impacts on women’s ability to make choices about their own reproductive rights, engaging them only as mothers and not as individuals in their own right. There has been no discourse around access to safe abortion, yet women have access to post-abortion care after an incomplete abortion; and while family planning is available, its inclusion in an essential benefits package remains unclear, given the lack of priority-setting around it.

Conclusion

UHC provides a unique opportunity for the progressive realisation of universal access to SRHR and the realisation of the right to the highest attainable standard of health for Kenya. However, its roll-out has been largely underwhelming and has mimicked many of the paternalistic traits in the delivery of health services that Kenyans experienced in their previous constitutional dispensation. SRHR encompass the whole life cycle of the individual from birth to old age and guaranteeing this, or even providing a discourse around its realisation, requires a recognition that SRHR exists beyond safe motherhood and newborn health.

References

- Constitution of Kenya (2010).

- United Nations General Assembly. Proclamation of Tehran; 1968 Dec 19. (A/RES/2442).

- United Nations General Assembly. Declaration on social progress and development; 1969 Dec 11. (A/RES/2542).

- Zampas C, Gher J. Abortion as a human right – international and regional standards. Hum Rights Law Rev. 2008;8(2):249–293. DOI:10.1093/hrlr/ngn008

- United Nations Population Fund. Programme of action of the international conference on population development; 1994 Sep 5–13. (A/CONF.171/13).

- World Health Organization. Defining sexual health: report of a technical consultation on sexual health [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. 35 p. (sexual health document series no. 1). [cited 2020 Oct 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/defining_sh/en/

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General comment no. 14: the right to the highest attainable standard of health (art. 12 of the Covenant); 2000 Aug 11. (E/C.12/2000/4). [cited 2020 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838d0.html

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General comment no. 22: the right to sexual and reproductive health (art. 12 of the Covenant); 2016 May 2. (E/C.12/GC/22). [cited 2020 Oct 21]. Available from: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/832961?ln=en

- African Union. Protocol to the African charter on human and people’s rights on the rights of women in Africa; 2003 Jul 11. [cited 2020 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3f4b139d4.html

- Federation of Women Lawyers & 3 others v Attorney General & 2 others (2019) Petition 266 of 2015.

- Health Act No. 21 of 2017 (KNY).

- African Union Commission. Maputo plan of action 2016–2030 for the operationalization of the continental policy framework for sexual and reproductive health and rights; 2015. [cited 2020 Oct 21]. Available from: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/24099-poa_5-_revised_clean.pdf

- World Health Organization. Recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. 77 p. [cited 2020 Oct 20]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275374/9789241514606-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- Merkur S, Sassi F, McDaid D. Promoting health, preventing disease: is there an economic case? [Internet] Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2015. 370 p.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Health promotion and disease prevention through population-based interventions, including action to address social determinants and health inequity [Internet]. Cairo. [cited 2020 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/about-who/public-health-functions/health-promotion-disease-prevention.html

- The Kenya National Health Policy 2014–2030.

- The Kenya National Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Policy 2015.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. School-based sexuality education programmes: a cost and cost-effectiveness analysis in six countries [Internet]; 2011. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?client=internal-element-cse&cx=000136296116563084670:h14j45a1zaw&q=http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/pdf/CostingStudy.pdf&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwj5hvibpsvsAhWioXEKHcMVADoQFjAAegQIBhAB&usg=AOvVaw0cJdjVvDFLOZ0l-m2fjDFI

- Fonner V, Armstrong K, Kennedy C, et al. School based sex education and HIV prevention in low and middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):18, Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24594648

- Maticka-Tyndale E. A multi-level model of condom use among male and female upper primary school students in Nyanza, Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(3):616–625. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20570426

- Guttmacher Institute. Adding it up: investing in contraception and maternal and newborn health for adolescents in Kenya [Internet]. Guttmacher Institute; 2019. [cited 2020 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/adding-it-up-contraception-mnh-adolescents-kenya#

- Campos N, Kim J, Castle P, et al. Health and economic impact of HPV 16/18 vaccination and cervical cancer screening in Eastern Africa. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(11):2672–2684. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21717458/

- United Nations Population Fund. Sexual and reproductive health and rights: an essential element of universal health coverage; 2019 Nov.

- World Health Organization. Universal health coverage [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2019. [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)

- World Health Organization. The fifty-eighth world health assembly. Geneva; 2005. (WHA58/2004/REC/1). Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA58-REC1/english/A58_2005_REC1-en.pdf

- World Health Organization. Health financing for universal coverage [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health_financing/strategy/dimensions/en/

- World Health Organization Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Bull Worl. 2014;92(6):389.

- Kalipso C, Glassman A, Marten R, et al. Priority-setting for achieving universal health coverage. Bull World. 2016;9(1):12. Available from: http://www.who.int/bulletin/online_first/BLT.15.155721.pdf

- Yamin AE, Maleche A. Realizing universal health coverage in East Africa: the relevance of human rights. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2017;17(21). Available from: https://bmcinthealthhumrights.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12914-017-0128-0

- Daniels N. Accountability for reasonableness: establishing a fair process for priority setting is easier than agreeing on principles. British Med. 2000;321(7272):1300–1301.

- Gonzalez-Pier E, Gutierrez-Delgado C, Stevens G, et al. Priority setting for health interventions in Mexico’s system of social protection in health. Lancet. 2006;368(9547). Available from: thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(06)69567-6/fulltext

- Okech A, Atieno W, Fredrick F, et al. Under Linda Mama, a woman was supposed to walk in and out of a hospital without paying a cent. Daily Nation; 2020 Jan 13). Available from: https://www.nation.co.ke/health/Paying-for-a-free-service/3476990-5416572-10d8p59z/index.html

- World Health Organization. Universal health coverage – the best investment for a safer, fairer and healthier world [Internet]. Youtube; 2017. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C1bIjISMlTo&list=PL9S6xGsoqIBWsxThBfcdFgGtCInYOl774&index

- Barasa E, Nguhiu P, McIntyre D. Measuring progress towards sustainable development goal 3.8 on universal health coverage in Kenya. BMJ Glo. 2018;3(3). Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/3/e000904

- Kariuki S. Roadmap to attain universal health coverage in Kenya by 2022. Cabinet memorandum, Republic of Kenya; 2018 Feb 19.

- World Health Organization. Human rights and health [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2017. [cited 2020 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health

- KTN News Kenya. What is envisioned in universal health coverage? [Internet]. Kenya: Youtube; 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9fFTUWIrZXA

- Ministry of Health. UHC phase 1 implementation plan, Republic of Kenya.

- The National Treasury and Planning. Budget statement for financial year 2019/20 [Internet]. 2019 Jun. Available from: https://www.treasury.go.ke/component/jdownloads/send/201-2019-2020/1442-budget-statement-for-fy-2019-20-final.html?option=com_jdownloads

- Amoth P. Lessons learnt from UHC; 2019.

- Lelegwe S, Okech T. Analysis of universal health coverage and equity on health care in Kenya. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8(7):218–227.

- Parliamentary Budget Office. Unpacking of the 2019 budget policy statement; 2019 Feb.

- World Health Organisation Africa. Building health: Kenya’s move to universal health coverage [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2018. [cited 2020 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/building-health-kenyas-move-universal-health-coverage

- Kawira Y. State committed tenents of universal health coverage. The Standard [Internet]; 2019 Apr 7. Available from: https://www.health.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/WORLD-HEALTH-DAY-SUPPORT-07-04-2019.pdf

- Kariuki S. Celebrating Kenya’s journey towards universal health coverage. The Standard [Internet]; 2019 Apr 7. Available from: https://www.health.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/WORLD-HEALTH-DAY-SUPPORT-07-04-2019.pdf

- Ministry of Health. CS health launches UHC pilot registration [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2018. [cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.health.go.ke/cs-health-launches-uhc-pilot-registration-machakos-kenya-november-10-2018/

- National Hospital Insurance Fund (standard and special contributions) regulations of 2015 (KNY).

- Munge K, Mulupi S, Barasa EW, et al. A critical analysis of purchasing arrangements in Kenya: the case of the national hospital insurance fund. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(3):244–254.

- Ministry of Health. NHIF expert panel task force propose establishment of social insurance scheme [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.health.go.ke/nhif-expert-penal-taskforce-propose-establishment-of-a-social-insurance-scheme/

- Ministry of Health. UHC makes a good investment, CS Kariuki [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2019. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.health.go.ke/uhc-makes-a-good-investment-cs-kariuki/

- Health Benefits Package Advisory Panel. Health benefits package [Internet]; 2018. Available from: https://vision2030.go.ke/publication/health-benefits-package-advisory-panel/

- Oraro-Lawrence T, Wyss K. Policy levers and priority-setting in universal health coverage: a qualitative analysis of healthcare financing agenda setting in Kenya. BMC Heal. 2020;20:182. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7059333

- Mbau R, Kabia E, Honda A, et al. Examining purchasing reforms towards universal health coverage by the national hospital insurance fund in Kenya. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(19). Available from: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-019-1116-x#

- National Hospital Insurance Fund. Strides towards universal health coverage for all Kenyans – national hospital insurance fund report [Internet]; 2018 Aug. Available from: http://www.nhif.or.ke/healthinsurance/uploads/notices/NHIF_Performance_Report_2018_08.08.2018.pdf

- Kenya health sector strategic and investment plan June 2014–June 2018. DONE.

- The Kenya Gazette. Gazette notice no. 5627 on advisory panel for the design and assessment of the Kenya UHC essential benefit package [Internet]. Vol. CXX. Authority of the Republic of Kenya; 2018. Available from: http://kenyalaw.org/kenya_gazette/gazette/volume/MTgwMw–/Vol.CXX-No.69/

- Kokwaro G. Universal health coverage health benefits advisory panel report on the UHC – essential benefits package; 2018.

- Third National UHC Conference 2019. Revitalizing primary health care for universal health coverage [Internet]; 2019. Available from: http://kma.co.ke/component/content/article/79-blog/96-3rd-kenya-national-uhc-conference?Itemid=437

- County Government of Kisumu. Annual state of the county report [Internet]; 2019 Nov. Available from: https://www.kisumu.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Kisumu-County-Report-2019.pdf

- World Health Organization. Universal health coverage: launch of pilot programmes in Kenya [Internet]. Youtube; 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=6&v=5plA6EiTw4k&feature=emb_title

- Anyango L. Treating Kisumu [Internet]. County Government of Kisumu; 2019. [cited 2020 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.kisumu.go.ke/tag/uhc/

- Otieno K. More Kenyans enlist for UHC despite setbacks. The Standard [Internet]; 2019 Nov 30. Available from: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001351437/more-kenyans-enlist-for-uhc-despite-setbacks

- World Bank. Moving toward UHC in Kenya: national initiatives, key challenges, and the role of collaborative activities [Internet]. Available from: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/852031513147721578/pdf/122044-BRI-Moving-Toward-UHC-series-PUBLIC-WorldBank-UHC-Kenya-FINAL-Nov30.pdf

- Oketch A, Kabale N. UHC programme hits a snag as drugs run out in pilot counties. Daily Nation [Internet]; 2019 Sep 3. Available from: https://nation.africa/kenya/news/uhc-programme-hits-a-snag-as-drugs-run-out-in-pilot-counties-200366

- Strategic Purchasing for Primary Health Care. A review of Afya Care – the universal health coverage pilot program in Isiolo County [Internet]; 2020 Feb. Available from: https://thinkwell.global/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Isiolo-UHC-pilot-brief_11-September-2020.pdf

- Otieno J. State puts on a brave face amid teething UHC challenges. The Standard [Internet]; 2020 Jan 4. Available from: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/health/article/2001355245/state-puts-on-a-brave-face-amid-teething-uhc-challenges

- McCollum R, Theobald S, Otiso L, et al. Priority setting for health in the context of devolution in Kenya: implications for health equity and community-based primary care. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(6):729–742. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29846599/

- Saoyo TG, Were N. Hinging maternal health services on NHIF – a critique of the constitutional legality of the Linda Mama programme [Internet]. KELIN Kenya; 2019. [cited 2020 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.kelinkenya.org/hinging-maternal-health-services-on-nhif-a-critic-of-the-constitutional-legality-of-the-linda-mama-programme/

- Ministry of Health, World Health Organization, World Bank, Government of Japan, United Nations Population Fund. Refocusing on quality care and increasing demand for services; essential elements in attaining universal health coverage in Kenya; 2019.

- Oluoch J. Civil society and communities demand a rights-based approach to the rollout of UHC in Kenya [Internet]. KELIN Kenya; 2019. [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.kelinkenya.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/UHC-Position-Statement-by-Kisumu-CSO-at-the-3rd-UHC-Conference_17052019.pdf

- County Government of Kisumu. Kisumu UHC mop up begins [Internet]. Kisumu County; 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.kisumu.go.ke/news-item/kisumu-uhc-mop-up-exercise-begins. Council of Governors. Launch of the universal health coverage pilot [Internet]. Council of Governors; 2018. [cited 2020 Sep 23]. Available from: https://cog.go.ke/component/k2/item/122-launch-of-the-universal-health-coverage-pilot

- Fried ST, Khurshid A, Tarlton D, et al. Universal health coverage: necessary but not sufficient. Reprod Health Matter. 2013;21(42):50–60.

- The Penal Code. Chapter 63 of the laws of Kenya.

- EG & 7 others v Attorney General; DKM & 9 others (interested parties); Katiba Institute & another (Amicus Curiae) (2019). Petitions 150 and 234 of 2015.

- Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. Realising sexual and reproductive health rights in Kenya: a myth or reality [Internet]; 2012 Apr. Available from: http://www.knchr.org/portals/0/reports/reproductive_health_report.pdf

- National Hospital Insurance Fund. Linda Mama services [Internet]. National Hospital Insurance Fund. [cited 2020 Oct 21]. Available from: http://www.nhif.or.ke/healthinsurance/lindamamaServices

- Oketch A, Kabale N. UHC programme hits a snag as drugs run out in pilot counties. Daily Nation [Internet]; 2019 Sep 3. Available from: https://nation.africa/kenya/news/uhc-programme-hits-a-snag-as-drugs-run-out-in-pilot-counties-200366