ABSTRACT

In 2006, abortion in Colombia was decriminalised under certain circumstances. Yet some women continue to avail themselves of ways to terminate pregnancies outside of the formal health system. In-depth interviews (IDIs) with women who acquired drugs outside of health facilities to terminate their pregnancies (n = 47) were conducted in Bogotá and the Coffee Axis in 2018. Respondents were recruited when they sought postabortion care at a health facility. This analysis examines women’s experiences with medication acquired outside of the health system for a termination: how they obtained the medication, what they received, how they were instructed to use the pills, the symptoms they were told to expect, and their abortion experiences. Respondents purchased the drugs in drug stores, online, from street vendors, or through contacts in their social networks. Women who used online vendors more commonly received the minimum dose of misoprostol according to WHO guidelines to complete the abortion (800 mcg) and received more detailed instructions and information about what to expect than women who bought the drug elsewhere. Common instructions were to take the pills orally and vaginally; most women received incomplete information about what to expect. Most women seeking care did not have a complete abortion before coming to the health facility (they never started bleeding or had an incomplete abortion). Women still face multiple barriers to safe abortion in Colombia; policymakers should promote better awareness about legal abortion availability, access to quality medication and complete information about misoprostol use for women to terminate unwanted pregnancies safely.

Résumé

En 2006, l’avortement en Colombie a été dépénalisé dans certaines circonstances. Pourtant, les femmes continuent d’avoir recours à des moyens d’interrompre leur grossesse en dehors du système de santé formel. Des entretiens approfondis avec des femmes qui avaient acheté des médicaments hors des centres de santé pour avorter (n = 47) ont été réalisés à Bogotá et dans la région connue sous le nom d’axe des producteurs de café en 2018. Les répondantes ont été recrutées quand elles ont demandé des soins post-avortement dans un centre de santé. Cette analyse examine l’expérience des femmes avec les médicaments achetés en dehors du système de santé pour une interruption de grossesse: comment elles ont obtenu les produits, qu’est-ce qu’elles ont reçu, comment on leur a conseillé d’utiliser les pilules, les symptômes escomptés et leur expérience de l’avortement. Les répondantes avaient acheté les médicaments dans des pharmacies, en ligne, auprès de vendeurs ambulants ou par des contacts sur leurs réseaux sociaux. Les femmes qui avaient fait appel à des vendeurs en ligne avaient reçu plus fréquemment la dose minimale de misoprostol conforme aux recommandations de l’OMS pour mener l’avortement à bien (800 mcg) et avaient obtenu des instructions et informations plus détaillées sur ce à quoi elles devaient s’attendre que les femmes qui s’étaient procuré le médicament ailleurs. Les instructions habituelles étaient de prendre les pilules par voie orale et vaginale; la plupart des femmes avaient reçu des informations incomplètes sur ce à quoi elles devaient s’attendre. La majorité des femmes demandant des soins n’avaient pas avorté totalement avant de se rendre au centre de santé (elles n’avaient jamais commencé à saigner ou avaient eu un avortement incomplet). Les femmes rencontrent encore de multiples obstacles à un avortement sans risque en Colombie; les décideurs devraient promouvoir une connaissance accrue de la disponibilité de l’avortement légal, de l’accès à des médicaments de qualité et à des informations complètes sur l’emploi de misoprostol pour les femmes qui veulent interrompre leur grossesse en toute sécurité.

Resumen

En el año 2006, Colombia despenalizó el aborto bajo ciertas circunstancias. Sin embargo, algunas mujeres continúan recurriendo a maneras de interrumpir el embarazo fuera del sistema de salud formal. En 2018, se realizaron entrevistas a profundidad (EAP) con mujeres que adquirieron medicamentos fuera de establecimientos de salud para interrumpir su embarazo (n = 47) en Bogotá y en el Eje Cafetero. Las entrevistadas fueron reclutadas cuando buscaron atención postaborto en un establecimiento de salud. Este análisis examina las experiencias de las mujeres con medicamentos adquiridos fuera del sistema de salud para la interrupción del embarazo: cómo obtuvieron el medicamento, qué recibieron, cómo se les indicó que usaran las pastillas, qué síntomas se les dijo que podrían esperar y cuáles fueron sus experiencias de aborto. Las entrevistadas compraron los medicamentos en farmacias, por internet, de vendedores ambulantes o por medio de contactos en sus redes sociales. Las mujeres que usaron vendedores en línea más comúnmente recibieron la dosis mínima (800 mcg) de misoprostol según las directrices de la OMS para tener un aborto completo y recibieron instrucciones más detalladas e información sobre qué esperar, comparadas con las mujeres que compraron el medicamento en otro lugar. Las indicaciones comunes fueron tomar las pastillas por vía oral y vaginal; la mayoría de las mujeres recibieron información incompleta sobre qué esperar. La mayoría de las mujeres que buscaron atención postaborto no tuvieron un aborto completo antes de acudir al establecimiento de salud (nunca presentaron sangrado ni tuvieron un aborto incompleto). Las mujeres aún enfrentan múltiples barreras para tener un aborto seguro en Colombia; los formuladores de políticas deberían promover mejor conciencia de la disponibilidad de servicios de aborto legal, acceso a medicamentos de calidad e información completa sobre el uso del misoprostol para que las mujeres puedan interrumpir embarazos no deseados de manera segura.

Introduction

In 2006, a constitutional ruling in Colombia overturned an absolute ban on induced abortions and decriminalised the procedure in cases of physical or mental health, rape or incest, and fetal malformations incompatible with life.Citation1 However, women still face multiple barriers accessing legal abortion care, including restrictive interpretation of the law by health providers, and health institutions’ overall disregard for legal abortion provision.Citation2,Citation3 Additionally, because a large proportion of women understand the health indications for legal abortion to be limited in a way that they are not in actuality, they often assume their cases would not meet the legal criteria.Citation4 Misoprostol was approved by the National Institution of Medication Surveillance (INVIMA) [Colombia] in 2007 and is legally available with a prescription under three brands: Cytil, Industol and Misopros. Mifepristone was registered (legalised) in 2017; evidence suggests that it is not widely used, and only available in health facilities.Citation5

Misoprostol became accessible in Latin America during the late 1980s and early 1990s.Citation6,Citation7 There is no clear explanation of how its use for abortion was disseminated across the region; several studies have documented how women access it in countries with legal restrictions including Brazil, Ecuador, Peru and México.Citation6–9 Drug stores have been described by these studies as one of the primary sources of informal misoprostol sales, and yet they frequently provided poor quality information about the dosages and the routes of administration, often leading to incomplete abortions.Citation8 In Colombia, misoprostol became available beginning in the early 1990s at drug stores. At that time, misoprostol was thought to serve as a mechanism to start an abortion; women used it and then procured postabortion care in a health facility.Citation7 Accessing misoprostol through informal sales has been found to take an emotional toll: before abortion was decriminalised in 2012 in Uruguay, informal misoprostol use carried notorious challenges for women including finding a source to buy it, experiencing anxiety when using it and using several doses.Citation9

The desire for privacy, lack of awareness about legal abortion as well as restricted access to legal abortion care,Citation10,Citation11 and the persistence of abortion methods women sought before the law changed, mean that women continue to use non-institutional means of interrupting their pregnancies including obtaining abortion medications through informal vendors.Citation12 Shortly after the decriminalisation of abortion, one study found that almost all abortions in Colombia were still occurring outside the legal framework.Citation3 There are no current data on the proportion of women seeking to end their pregnancies through this means. Though medical abortion (MA) outside the clinical context can be a safe means of pregnancy termination,Citation13 when inadequate or inaccurate information or ineffective pills are provided, the use of medications acquired informally may result in complications including incomplete abortion, prolonged bleeding or pregnancy continuation.Citation14–16

Women’s experiences using misoprostol acquired from informal sources to induce abortion in Colombia have remained unexplored. To address this gap, we undertook a study to understand where women access misoprostol and how they use it to try to terminate unwanted pregnancies. We recruited women obtaining postabortion care to explore their experience of obtaining misoprostol informally. Here we examine: women’s experiences obtaining the medication, what women received when they sought to terminate a pregnancy with medication, how women seeking to induce abortion were told to take the MA pills and what physical experiences they were told to expect, and women’s abortion experiences with misoprostol.

This work is part of a larger project examining informal access to and use of misoprostol in Colombia, Indonesia and Nigeria using a mystery client methodology to attempt to purchase misoprostol from drug sellers, a survey with drug sellers about what they do when women come seeking something to terminate pregnancies, and interviews with women who attempted to abort using MA drugs. Other results from this study have been published elsewhere.Citation5,Citation17,Citation18

Methods

The study was a collaboration between the Guttmacher Institute, a sexual and reproductive health research and policy institute in the United States, and Fundación Oriéntame, a private non-for-profit abortion provider based in Colombia. Data collection took place between May and July 2018 at two Fundación Oriéntame clinics, one in Bogotá and the other in the Coffee Axis (Eje Cafetero) in the town of Pereira. Bogotá is the capital of Colombia; it has a population of 7.2 million (the country’s population is 44.1 million).Citation19 The Coffee Axis includes the mid-size metropolitan cities of Pereira, Manizales and Armenia. The estimated total population of Pereira, Armenia, and Manizales is approximately 1.1 million.Citation19

In addition to other types of reproductive health care, both clinics provide postabortion check-ups to women who are interested in confirming the success of an induced abortion conducted with informally acquired medication. These two locations were chosen because they have concentrations of reproductive medical services that serve the population of those areas and the surrounding vicinity; we did not anticipate women’s experiences to be different in the two locations.

Interviewers were hired from the two regions who had previous experience in health care research and/or social work. Four interviewers as well as a research assistant were trained by the authors (JO, AMM and CV) on in-depth interviewing and study protocol, including the consent process and in-depth interview guide. Two interviewers and the research assistant were based in the Coffee Axis, and the other two interviewers in Bogotá. Both sets of interviewers were present at their respective facilities each day of the fielding period and were supervised by the in-country study coordinator (JO) with the support of the research assistant.

Sample and recruitment

Women 18 years of age or older (i.e. minors were excluded) who took (what they thought was) MA pills in tablet form acquired in the informal sector, and subsequently sought postabortion check-ups at the two Oriéntame clinics in this sample, were eligible for recruitment into the study. MA was with mifepristone and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone, no matter what administrative route the woman used. We included women who may have experienced a complete abortion using MA and just wanted confirmation that the abortion was complete, as well as women who had used MA and were experiencing symptoms of an incomplete abortion or a continued pregnancy. The informal sector is defined as accessing MA from drug sellers without a prescription, from online sellers or through personal networks. Some eligible women declined to participate because they did not have time to sit down for an interview, or, after consenting to participate, did not appear for the interview at the agreed time. Overall, 47 women were interviewed, 27 from Bogotá, and 20 from the Coffee Axis. The difference in sample size between the two sites is a combination of client flow and women’s willingness to participate.

After an eligible woman received her postabortion care, the provider told her about the study being conducted at that facility but did not elaborate on the content of the research. If the patient consented to learn more, the provider introduced her to one of the interviewers who told her more about the study. Sometimes the interview took place immediately or was scheduled to take place at a later time (on the same day or the following day). At the start of the interview, the interviewer administered the consent form. The audio recorder was turned on once the woman agreed to participate. Each woman was compensated 96,000 Colombian pesos (∼US$ 32) for her time plus 15,000 Colombian pesos (∼US$ 5) for transportation. The Comité de Ética en Investigación de la Fundación Oriéntame [Colombia] and the Institutional Review Board of the Guttmacher Institute approved this protocol.

Data collection

All interviews were conducted in Spanish. Interviews covered the woman’s decision-making about ending the pregnancy, her experience acquiring the pills including her interaction with the seller, what the seller communicated to her about taking the pills, her experience taking the pills, support she had during the process, care-seeking, her misoprostol literacy, her intention to use contraception, what she thinks she would have done to end the pregnancy if she had not been able to access misoprostol, and her recommendations for other women going through a similar experience. (See Supplemental Material.) We used visual aids to help women identify the pills that they obtained. Interviews lasted on average one hour.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed by a transcriptionist who was not an interviewer. The transcripts were then checked by JO for accuracy and de-identification. A coding structure was developed using NVivo 11 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) based on the questions covered in the interview guide, and all interviews were coded into this node structure so that the data could be compared according to primary domains of interest. Once the interviews were coded, following Miles and Huberman,Citation20 the bilingual analysis team created matrices to identify primary themes emerging on domains of interest. The analysis was stratified according to where the woman bought the drugs (drug shops, online sellers, elsewhere) to be able to see how their experiences differed. From the matrices, bullet points were created by the same team to summarise the salient points that emerged. Quotes were translated during analysis when they were selected for inclusion in the paper to illustrate relevant points.

The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for misoprostol-only first-trimester abortion recommend an initial dose of 800mcg of misoprostol (taken sublingually, vaginally or buccally), followed by subsequent 800mcg doses as needed.Citation21 We benchmarked women’s use of misoprostol against this. WHO guidelines also indicate that users of misoprostol for pregnancy termination should be informed of: physical effects (abdominal cramping and menstrual-like bleeding), potential side effects (nausea/vomiting and diarrhoea), and signs of possible complications (increased intensity/prolonged abdominal cramping, excessive bleeding, and prolonged fever or chills).Citation21–23 If a respondent reported that she was advised on the two physical effects, two side effects, and three complications, we determined that the seller had provided the minimum essential information.

Results

Description of the sample

The women in our sample ranged from 18 to 37 years of age, with most respondents (n=34) in their twenties (). Respondents largely obtained medications for abortion from drug storesFootnote** (n = 21) and online sellers (n = 16), while the remainder (n = 10) obtained them from other sources including street vendors or through contacts in their social networks. Ten respondents indicated they were currently in a union. All but seven respondents had an education level of secondary school or higher, while 32 respondents indicated they were currently employed. Over half (n = 27) had experienced at least one birth prior to this pregnancy they sought to terminate.

Table 1. Description of sample, Colombia 2018

Women’s experiences obtaining medications

Thirty-eight out of 47 women bought the medication themselves. This includes all the women who purchased the medication at drug stores or from online sellers, as well as one who obtained the medication from a street seller.

“My friend told me [how to do it as] she had done it [bought misoprostol] before. She said I should go to a pharmacy named [name of pharmacy] and ask for a man called ‘el calvito’ [the little bald guy]. So I went to the pharmacy and he sold me the pills.”

(24 years old, works outside her home, obtained her medication through a drug store, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

“So I told that guy because he had to know [I was pregnant]. [ … ] The guy told me that there were some pills called misoprostol, or something like that. I took those pills and they didn’t work.”

(25 years old, working outside home, obtained her medication through the man who sexually assaulted her, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

Another woman asked a female friend who had previously obtained abortion medication for herself to procure the misoprostol. In two cases, women asked health professionals with whom they had personal connections (a medical doctor and a nurse) to secure the medication for them.

Among women who acquired medication for abortion from a drug store (n = 21), they reported that they asked for medications to abort or just requested Cytotec. Despite the brand not being registered in Colombia, “Cytotec” is a popular way to reference misoprostol. One respondent reported that she told the drug seller she had a menstrual delay. Women who obtained medicines online related that they (or an intermediary) searched for terms including “aborto casero” [home abortion], “cómo interrumpir un embarazo” [how to interrupt a pregnancy], “pastas para abortar” [abortion pills] and “pastillas Cytotec” [Cytotec pills]. Online sellers communicated with the respondents or their proxies through WhatsApp, except for one seller who asked the woman to communicate with him solely through a voice call. Online sellers offered women different options to get misoprostol: either delivered to their house via courier service or be picked up at certain public spots in city (e.g. bus stations). When women met these sellers to obtain the pills, payment and delivery took place very quickly.

Women related that vendors generally only asked one of two questions: how long she thought she had been pregnant or how many pills she wanted. Most women reported to the sellers that they were between four and eight weeks pregnant, with the range between two and 13 weeks gestation. Some online sellers asked women how sure they were about their decision.

What women received to terminate their pregnancies

Regardless of the source of the medications, women were usually sold four to six pills of what they thought was misoprostol (most likely 200 mcg each) (). Drug sellers (including all sources) would sell more (up to 10 pills) if the woman thought she was further along in her pregnancy. Most women identified the misoprostol they received by its brand, either Cytotec (n = 35) or Cytil (n = 2). The other women could not clearly identify the pills that they received, though with the help of the visual aids a few identified the pills they had been sold as white and hexagonal, the form in which some misoprostol including Cytotec is produced. While we cannot be certain about what medications the women received, all respondents believed they had purchased and used misoprostol.

Table 2. Characteristics of abortion experience, Colombia 2018

Over a third of respondents (17 of 47), no matter the source from which they got the drugs, received an additional medication to the misoprostol. Just under half (10/21) who bought abortifacients in drug shops were told that the full MA regimen included misoprostol pills and injections. They received the injection at the drug store. Some women reported they had been injected with oxytocin (Pitocin), while most did not know what injection(s) they had been given. A nurse told one respondent who asked what was in the injection, “The less you know, the better.” They described feeling pain when being injected.

He gave me an injection and told me that was five-in-one. [ … ]

What does five-in-one mean?

[The content of] five injections in one, so it is the strongest injection. [ … ] He told me to pull down my pants and he gave me the injection. When the liquid got inside me it hurt a lot. I cried because I could not stand the pain, I couldn’t walk and I could not feel my buttock. (23 years old, studying in a technical program and working, obtained her medication through a drug store, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

“The lady who sold the pills [ … ] said that [ … ] I had to drink herbs all day long, a whole pot of herbs, but I don’t know which kind of herbs they were. [ … ] I don’t know … She didn’t say which herbs they were, but she gave them to me and insisted that I should take them so that they clean everything that was going to come out.”

(24 years old, working outside home, obtained her medication through a seller located in an informal market, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

Thirteen women reported two or more attempts to induce the abortion (). Three women had initially attempted to acquire misoprostol from drug stores but were told that this medication could not be sold without a prescription, so they resorted to online sellers. Some women who bought pills that did not result in an abortion contacted the seller again for more medication. When the pills did not work, sometimes the seller who sold them the misoprostol referred them to an abortion clinic, a private doctor or public hospital. Some women went to an abortion clinic on their own without recontacting the seller.

How women were instructed to use the pills and what they were told to expect

The majority of women in our sample or their intermediaries were provided with instructions by the seller on how to take the medication. Respondents reported a range of regimens were recommended by the sellers. Twenty-seven respondents were advised to just take one dose of misoprostol containing between three and eight pills, while the remaining women were instructed to take up to five doses of pills across various time periods ranging from a few hours to a few days. Almost all women receiving misoprostol from online sellers reported receiving instructions; these online sellers provided instructions via WhatsApp, on papers delivered with the pills, or via email. One woman shared with the study members the instruction sheet that the online seller sent her. It included information on misoprostol’s effectivity (95% effective until 63 days of gestation), how to administer the pills (two oral and two vaginal), what to expect after using misoprostol (bleeding, cramps, clots and seeing pregnancy tissue), what to do in case the pills didn’t work (take a second dosage of misoprostol 24 hours later and, if it also failed, a third dosage 48 hours after the second dosage), what pills to take to control pain (500 mg) and how to confirm the success of the abortion (take a pregnancy test or get a transvaginal ultrasound).

Advised routes of administration tended to vary by seller type. Drug store vendors and other types of sellers (not online sellers) typically told women to use combined routes of oral and vaginal administration, and to insert pills vaginally with an applicator. Only seven women reported that a seller from one of these categories told them to take the misoprostol sublingually. Two women, one who obtained the medication from a drug store and one whose friend purchased it for her through a contact, did not receive instructions; the former found instructions on how to use the drug online, while the latter followed instructions her friend provided.

The most common instruction for women who acquired their misoprostol from drug stores and online sellers was to use misoprostol at night while lying in bed, to prevent vaginally inserted pills from “falling out”. Women were told to lift up their legs from twenty minutes up to four hours until the misoprostol dissolved.

“He gave me the injection and told me that in ten minutes I had to take two [pills], at two hours I had to take two more [pills], and at two hours I had to take another two [pills] and the next two hours I had to take the other two [pills]. When I got home, I had to do the intravaginals [vaginal insertion] … I went pee, lay down on the bed, introduced the pills intravaginally, and stayed with my feet up for twenty [minutes], half an hour.”

(<25 years old, studying in a technical program and working, obtained her medication through a drug store, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

What symptoms did it say on the paper you were going to feel?

It said that the pills could cause dizziness, that it could then produce strong cramps, that the pills could result in numbness of the abdomen, fever, too. That if the fever was very high then one had to go to a doctor. They were very careful to explain what to do in case of emergency.

For example, in case of fever go to the doctor?

A fever higher than forty degrees [Celsius].

What else would mean you had to go to the doctor? What other symptoms? For example, bleeding?

Bleeding but heavy bleeding after a week. If heavy bleeding and strong cramping continues, then go … [The instruction was] not so specific, that is, it was specific in the process but not so much in what happened after the abortion occurred, which was what shocked me the most. … You really feel alone doing it. They say you can call if you have a problem, but there’s no one really taking care of you.

(<25 years old, with a college education, obtained medications from an online seller, completed abortion before arriving at the health facility)

How women took the MA pills

Most women took the medication as instructed (41 of 47). Of the six who did not, half of them had purchased their medication from the online sellers. A few women took fewer pills than suggested by the drug seller because they did not have enough money to buy all the recommended pills, and they had read on the web that they could use fewer pills than the amount recommended by the seller. Most respondents did not report difficulty in following the instructions they received and used the medications provided on their own, inserting the pills vaginally by themselves with an applicator or their fingers. But for some women, inserting the pills was more complicated.

I put them in with an applicator. [Then] I stuck my finger [in] to see if they were alright, and I was already full of blood. Well the truth is … I still ask myself that question, because I do not know if it was the device that hurt me or the pills … [ … ]

It’s like what material?

Plastic. It’s transparent.

Like the plastic speculums?

Yes, ma’am. Of that material, it’s plastic and it’s like two fingers, that long. Well, when I saw blood on my finger, I went and I bathed. I said “No, [I’m bleeding] because the pills are already working. It’s super strong, it’s really going to start to hurt a lot. Because it started working immediately.”

(<25 years old, completed secondary schooling, obtained her medication through a drug store, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

“At the drug store, they asked me if I had someone to insert the pills, and I said no. Then she gave me the address of the lady [ … ]. No, that lady … uh, it was revolting. That lady came and told me to ‘enter the bathroom’ [ … ] and I looked with disgust because I did not want to urinate there. [ … ] And in the bed where I lay down, there were two little girls - they were asleep, and she put a blanket on me so the girls would not see. It was a normal lady, but the house was not a house that one would say was adequate, nor could one say that it was clean, because it was not … but as I said, in the midst of despair one makes many dumb choices. [ … ] I mean, she introduced the speculum into me and with two sticks [two chopsticks] like that she introduced the pills.”

(<25 years old, had not completed secondary school, obtained medications through a drug store, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

Women’s abortion experiences using misoprostol

Cramping and bleeding, whether described as mild or heavy, were the most commonly mentioned symptoms. In the majority of the cases where heavy cramping occurred (22 cases), women described it as “excruciating pain”, “unbearable pain”, and the “worst pain ever experienced in life”.

“And it started to hurt me like nothing has ever hurt me in this life. It lasted about half an hour; I was in the bathroom literally in a fetal position. That was the only position that I could tolerate being in [ … ] it hurt too much. I could not stretch out, but neither could I curl up any more. I could not stand any position, everything hurt. I was restless, I moved from side to side, nothing felt better and it did not stop hurting. [ … ] I was hungry and I felt very weak, and in a moment the pain was so strong that I felt that I lost consciousness because of the pain. Well, the truth is that I never felt anything in my life had hurt in that way. But I knew that I would be able to bear it.”

(<25 years of age, with a college education, obtained medications from an online seller, completed the abortion before arriving at the health facility)

Ten women who bought misoprostol from drug stores did not experience bleeding, along with five women who bought pills online, and three women who got pills from other sellers – despite it being the primary symptom evincing that the medicine has functioned. Some of these women did experience “incredible” cramps, as well as nausea, vomiting, fever, diarrhoea, and what some described as “uncontrollable chills”. Of seven cases of intense cramping and bleeding, three resulted in abortions which were completed before the woman arrived at the clinic.

Ten women experienced mild bleeding or no cramping. They described their symptoms as similar to a normal period. A few reported also experiencing nausea, a headache, dizziness, weakness. The woman quoted below had two injections from a drug seller who told her to take the misoprostol pills at home. She took the pills by herself:

“At around 3am I awoke and I went to the bathroom and I had bleeding, but it wasn’t so much. I didn’t have cramps … I didn’t feel anything else … But the other day, I didn’t have the capacity to even get out of bed. I was feeling really nauseated, lots of weakness, that’s what I felt … [the most I felt was] nausea, ill, or, I could describe it as feeling super weak. I couldn’t get out of bed … just nausea, lots of nausea, I saw points of light … lights … but nothing else.”

(25 or older, completed university, obtained medications from a drug store, abortion was not complete when she arrived at the health facility)

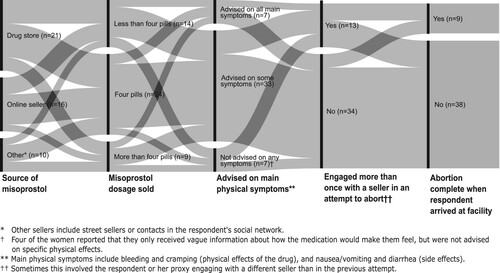

represents the experiences of women through the process of acquiring MA drugs to the time they arrived at the health facility. Women’s interactions with the first seller they contacted are summarised in the figure; 34/47 interacted with one seller before arriving at the health clinic while the remaining 13 interacted with two or more sellers before they arrived at the health clinic. The length of the vertical black bars separating each panel shows the number of respondents in that category. The left-most section of the alluvial flow diagram (Panel 1) indicates the number of women who obtained medications from each of the different types of sellers. Panel 2 shows how many misoprostol pills women were sold by the first seller they contacted. As can be seen, women were advised to use different numbers of pills from each of these vendor categories, demonstrating the wide variability of information provided even within the same vendor type. Panel 3 shows whether respondents were advised on all, some, or none of the main physical symptoms associated with use of misoprostol (bleeding, cramping, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea). Again, it is possible to see that the information women received varied greatly and was not related to who sold them the pills or how many pills they received. Panel 4 shows the proportion of women who engaged more than once with a seller (either going back a second time to the same seller or reaching out to another seller) in an attempt to abort. Lastly, Panel 5 shows whether the woman was able to self-manage her abortion prior to arriving to the clinic. Most women did not have a successful abortion on their own; however, some of these women “travelled” the same path as women who did. We could conclude from this that women’s outcomes may in part depend on things that we couldn’t capture including drug quality, specifics of administration, health literacy in general and information received from other sources specifically, and women’s tolerance for uncertainty and/or coping with health matters on their own. It is important to keep in mind that these sample sizes are small and so the results are most helpful in demonstrating the range of women’s pathways through misoprostol acquisition to postabortion care.

Discussion

Drug stores, online sellers, street vendors and even informal contacts with medical providers are the sites where women seek MA drugs through the informal sector in Colombia. Most of the women bought the medication themselves. They exhibited a high level of trust of these informal vendors who advised them what to use to end the pregnancy. They asked few questions and used the medication for the most part as instructed. The narratives of our respondents indicate that they received instructions and medications provided by sellers under the assumption that these other medicines were essential to the successful completion of their abortion, when in fact the use of those additional medications is not supported by medical literature and they caused the women additional physical pain and distress. The motivation behind selling these additional medications is not clear; some sellers may indeed have been taking advantage of the opportunity to sell more products to a client, or the sellers may believe that these drugs do contribute to a successful abortion. If the cost of these additional drugs winds up delaying the abortion because the woman needs more time to come up with the money, the fact that they are being marketed as necessary for the abortion can make the abortion more dangerous. All but one woman, who had gotten her drugs from a feminist organisation, received inadequate information about the physical effects, side effects and possible complications they could expect to experience or should identify as warning signs that they needed care. Compared to other sources, women who bought the drugs online received more information. This may be why the women who used online sellers were more likely to be able to self-manage their abortion on their own. Yet the fact that 18 women in our sample reported that they never started bleeding after taking the misoprostol suggests that some of the pills women were sold were ineffective and therefore the woman would never have been able to complete the abortion on her own unless she acquired more misoprostol.

Most of the respondents in our sample (n = 38) arrived at the health facility without having completed the abortion. One possible reason for this is suboptimal administration of the medicine as advised by the sellers. More than half of sellers advised respondents to take all or some of the misoprostol orally. Oral administration of misoprostol is the least effective route of administration, and also results in more frequent side effects.Citation24,Citation25 Sellers that advised vaginal administration commonly told the woman to lie down after insertion. This recommendation is not based on medical evidence and has no impact on effectiveness. What may be more relevant is whether the pills are inserted deeply enough into the vagina or whether they are moistened prior to insertion;Citation24,Citation26,Citation27 respondents only reported being advised on deep insertion, but not on moistening the pills prior to insertion. Another point of consideration is that sellers often relied on the woman’s estimate of her menstrual delay/gestational age. If the woman calculated this information incorrectly, then the seller may not have provided the correct dose for her gestation.

Furthermore, the amount of medication some women were provided might have been insufficient to facilitate a complete abortion. Twenty respondents indicated that the full regimen of pills they were advised to take included four pills or less, with six women reporting that the initial suggested dose consisted of just two or three pills. Current WHO guidelines for misoprostol-only regimens in the first trimester recommend beginning with 800mcg of misoprostol and then taking additional doses as needed.Citation21 Multiple studies evaluating the use of misoprostol for first-trimester pregnancy terminations also suggest that a higher number of doses may contribute to higher rates of completion.Citation24,Citation28–30

Another possible reason could be the quality of medication they had received. Recent estimates from the WHO indicate that one in ten medical products in low- and middle- income countries are substandard or falsified.Citation31 Further, unregistered laboratories producing misoprostol have been discovered in Latin America.Citation32 The efficacy of the drugs produced by these unregistered laboratories is unknown.Citation32 It is likely that the drugs have been distributed throughout the region. Use of counterfeit medicine may yield severe health consequences including death, if they contain harmful substances.Citation31 Even vendors themselves may not know the quality of the drugs that they are selling. It is also possible that women were sold misoprostol that had degraded through improper packaging or storage, or that was past its shelf life. Many women reported receiving Cytotec from the seller. As this brand is not registered in the country, we can only hypothesise how the sellers came by these drugs and they may not all been properly manufactured or stored properly. Lastly, it is possible that women may not have received misoprostol at all.

Limitations

The respondents in this study are women above 18 years of age who sought postabortion care, either because their abortion was not complete or because they wanted to verify that their abortion was complete. All respondents had concerns about the effectiveness of the medicines they used or were experiencing complications, and do not represent the universe of misoprostol users. As we do not have a sample of the full universe of women using misoprostol acquired informally, we do not know the proportion of women who used drugs acquired informally and had a complete abortion without seeking any further medical care, nor do we know how these experiences differ for minors. Therefore, this sample and our findings underrepresent the experiences of women with successful abortions that had no lingering concerns. Furthermore, it is not possible to know what percentage of these women would have been able to successfully complete the abortion on their own had they not visited the health facility. This limitation is compounded by the fact that we were not able to capture good data on the length of time between when the women took the medications and when they arrived at the clinic. We also do not know what drugs the women actually received or their efficacy. In addition, eligible women who declined to participate may differ in ways that we cannot identify from the women who chose to participate. Lastly, we may not be drawing on the most salient information to understand successful self-management of abortion. Perhaps there are other elements which would more closely connect to women’s ability to successfully self-manage an abortion with misoprostol.

Policy recommendations

There may be many reasons that women continue to seek abortion from informal sellers. This study found that there is a lack of quality care when misoprostol is provided by informal sellers, even more so among drug store vendors than online sellers. The lack of quality of care encompasses the quality of drugs women are sold, the quality of information they receive about how to use the drugs, and the quality of information they receive about the physical symptoms, side effects and signs of possible complications. Ideally, they would also know exactly what medications were being given to them, at what dosages and what those drugs were meant to do. This would empower them to decline gratuitous medications offered to them that are not necessary for having a successful abortion. This lack of quality of care exposes women to multiple risks including continuation of an unwanted pregnancy that they may attempt to abort at a later gestation, incomplete abortions and potentially morbidity related to retained fetal parts or infection. At a minimum, policymakers need to ensure access to good quality medications. Improved information for women about MA drugs which could come from multiple formal venues including the Ministry of Health, as well as independent, reliable information sources, will help facilitate improved outcomes for women, and extract less of a burden on the health care sector to provide care for incomplete abortions and abortion complications. When women have incomplete information about the physical results of taking the drug, users may go through the process with fear and uncertainty, and they may seek unnecessary care because they are unsure whether what they are experiencing is normal. Multilevel pregnancy tests (MLPT), a uterine test that detects varying levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), can be used after the abortion to rule out ongoing pregnancy. Women should use two tests, the first before they take any abortion drug and the second 1–2 weeks later.Citation33 If MLPTs are not available, blood pregnancy tests can be done 4–5 days after the abortion to determine if it was successful. Incorporating this advice into the information given to women would also improve the quality of care they receive. Lastly, policymakers who are willing to bravely address the larger issue of why women are seeking abortions informally should expand the criteria for who can access safe abortion services from qualified providers, as well as expand the role of drug sellers to legally provide abortion drugs without a prescription. The costs of not expanding access will be women who risk their health and lives to terminate unwanted pregnancies. This research is able to make clear what some of those risks look like.

Women may be accessing drugs outside of the formal health care system for any number of reasons: they may be unaware of the availability of legal abortion care, they may be aware but think their circumstances would not qualify them for a legal abortion, the cost of an abortion in the formal sector may be prohibitive for them, and/or they may prefer the anonymity/privacy of buying drugs through informal vendors. Future research should explore why women seek to terminate their pregnancies informally, in order to identify possible ways of channelling these women towards qualified providers with access to reliable medications. This could serve to improve women’s abortion experiences by facilitating earlier abortions, shortening the duration of their abortion experience and minimising any physical complications from the abortion. Additional dimensions of influence such as health literacy, agency, naturally occurring differences in women’s reactions to misoprostol or their preference for medical care may also play a role in understanding if women are able to successfully self-manage abortions. These other influences should be included in future research in this area.

Conclusion

The respondents’ experiences give us insight into challenges that women experience acquiring and successfully using abortion drugs obtained through the informal sector in Colombia. The extent to which these women’s experiences are similar to women’s experiences in other places suggests that when misoprostol fails, women in more legally restricted settings will have fewer options to obtain/complete an abortion than the women in our sample, and the options available to those women will come with much greater risk. Access to MA is a harm-reduction strategy that must be preserved so that women are not compelled to resort to more dangerous abortion methods. Therefore, improving the experiences of women terminating unwanted pregnancies using informal access to MA will help to save women’s lives.

Supplemental Material (in Spanish)

Download MS Word (40.2 KB)Additional information

Funding

Notes

** We are using the term drug store rather than pharmacy because many of these vendors are not qualified or trained pharmacists.

References

- Ceaser M. Court ends Colombia’s abortion ban. The Lancet. 2006;367(9523):1645–1646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68715-1.

- González Velez AC, Castro L. Barreras de Accesso a la Interrupcion Voluntaria del Embarazo en Colombia. Bogotá: La Mesa por la Vida y la Salud de las Mujeres; 2017.

- Prada E, Biddlecom A, Singh S. Induced abortion in Colombia: new estimates and change between 1989 and 2008. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;37(3):114–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1363/3711411.

- González Vélez AC, Bohorquez Monsalve V, Castro González L, et al. (2016). Las causales de la ley y la causa de las mujeres. La implementación del aborto legal en Colombia: 10 años profundizando la democracia. La Mesa por la Vida y la Salud de las Mujeres.

- Moore AM, Blades N, Ortiz Romero J, et al. Women’s experiences accessing and using misoprostol acquired through the informal sector in Colombia. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46(4):294–300.

- De Zordo S. The biomedicalisation of illegal abortion: the double life of misoprostol in Brazil. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos. 2016;23(1):19–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702016000100003.

- Zamudio L, Rubiano N, Wartenberg L, et al. El aborto inducido en Colombia: características demográficas y socioculturales. Cuadernos del CIDS. 1999;3:15–157.

- Lafaurie MM, Grossman D, Troncoso E, et al. Women’s perspectives on medical abortion in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru: A qualitative study. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13(26):75–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26199-2.

- Rostagnol S, Viera M, Grabino V, et al. (2013). Transformaciones y continuidades de los sentidos del aborto voluntario en Uruguay: Del AMEU al misoprostol. http://clacaidigital.info:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/995.

- Baum S, DePiñeres T, Grossman D. Delays and barriers to care in Colombia among women obtaining legal first- and second-trimester abortion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet: Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(3):285–288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.036.

- DePiñeres T, Raifman S, Mora M, et al. “I felt the world crash down on me”: women’s experiences being denied legal abortion in Colombia. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):133, doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0391-5.

- Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, et al. Abortion worldwide 2017. Uneven progress and unequal access. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2019.

- World Health Organization. Health worker roles in providing safe abortion care and post-abortion contraception. World Health Organization; 2015.

- Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Baum SE, et al. Second-trimester medication abortion outside the clinic setting: An analysis of electronic client records from a safe abortion hotline in Indonesia. BMJ Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2018: 286–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2018-200102.

- Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Kristianingrum IA, et al. Effect of a smartphone intervention on self-managed medication abortion experiences among safe-abortion hotline clients in Indonesia: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;149(1):48–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13086.

- Sedgh G, Filippi V, Owolabi OO, et al. Insights from an expert group meeting on the definition and measurement of unsafe abortion. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016;134(1):104–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.11.017.

- Moore AM, Philbin J, Ariawan I, et al. Online misoprostol sales in Indonesia: A quality of care assessment. Stud Fam Plann. 2020;51(4):295–308.

- Stillman M, Owolabi O, Fatusi AO, et al. Women’s self-reported experiences using misoprostol obtained from drug sellers: a prospective cohort study in Lagos State, Nigeria. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5).

- Departamento Adminstrativo Nacional de Estadistica. (2019). Resultados del proceso de omisión censal para el Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2018. Departamento Adminstrativo Nacional de Estadistica. https://www.dane.gov.co/files/censo2018/informacion-tecnica/cnpv-2018-omision-censal.pdf.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE; 1994.

- World Health Organization. Medical management of abortion. World Health Organization; 2018.

- World Health Organization. (2012). Safe abortion: Technical and policy guidance for health systems. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/9789241548434/en/.

- World Health Organization. Clinical practice handbook for safe abortion. World Health Organization; 2014.

- Blanchard K, Shochet T, Coyaji K, et al. Misoprostol alone for early abortion: an evaluation of seven potential regimens. Contraception. 2005;72(2):91–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2005.02.008.

- Kulier R, Kapp N, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. Medical methods for first trimester abortion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(11), doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub4.

- Alexander NJ, Baker E, Kaptein M, et al. Why consider vaginal drug administration? Fertil Steril. 2004;82(1):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.01.025.

- Ngai SW, Tang OS, Chan YM, et al. Vaginal misoprostol alone for medical abortion up to 9 weeks of gestation: efficacy and acceptability. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(5):1159–1162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/15.5.1159.

- Carbonell JL, Varela L, Velazco A, et al. The use of misoprostol for abortion at ≤ 9 weeks’ gestation. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 1997;2(3):181–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/13625189709167474.

- Carbonell JLL, Rodríguez J, Velazco A, et al. Oral and vaginal misoprostol 800 μg every 8 h for early abortion. Contraception. 2003;67(6):457–462. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00043-X.

- Zikopoulos KA, Papanikolaou EG, Kalantaridou SN, et al. Early pregnancy termination with vaginal misoprostol before and after 42 days gestation. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(12):3079–3083. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.12.3079.

- World Health Organization. Substandard and falsified medical products. World Health Organization; 2018; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/substandard-and-falsified-medical-products.

- World Health Organization. WHO global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products. World Health Organization; 2017.

- Raymond EG, Shochet T, Blum J, et al. Serial multilevel urine pregnancy testing to assess medical abortion outcome: A meta-analysis. Contraception. 2017;95(5):442–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2016.12.004.