Abstract

Poor quality person-centred maternity care (PCMC) leads to delays in care and adverse maternal and newborn outcomes. This study describes the impact of spreading a Change Package, or interventions that other health facilities had previously piloted and identified as successful, to improve PCMC in public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India. A quasi-experimental design was used including matched control-intervention facilities and pre–post data collection. This study took place in Uttar Pradesh, India in 2018–2019. Six large public health facilities participated in the evaluation of the spread study, including three intervention and three control facilities. Intervention facilities were introduced to a quality improvement (QI) Change Package to improve PCMC. In total, 1200 women participated in the study, including 600 women at baseline and 600 women at endline. Difference-in-difference estimators are used to examine the impact of spreading a QI Change Package across spread sites vs. control sites and at baseline and endline using a validated PCMC scale. Out of a 100-point scale, a 24.93 point improvement was observed in overall PCMC scores among spread facilities compared to control facilities from baseline to endline (95% CI: 22.29, 27.56). For the eight PCMC indicators that the Change Package targeted, spread facilities increased 33.86 points (95% CI: 30.91, 36.81) relative to control facilities across survey rounds. Findings suggest that spread of a PCMC Change Package results in improved experiences of care for women as well as secondary outcomes, including clinical quality, nurse and doctor visits, and decreases in delivery problems.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04208841..

Résumé

La faible qualité des soins de maternité centrés sur la personne aboutit à des retards du traitement et à un mauvais état de santé maternelle et néonatale. Cette étude décrit l’impact du déploiement d’un ensemble de mesures de changement, ou d’interventions que d’autres établissements de santé avaient précédemment testées et jugées réussies, pour améliorer les soins de maternité centrés sur la personne dans des établissements de santé publique de l’Uttar Pradesh, Inde. Une conception quasi-expérimentale a été utilisée, avec des établissements témoins ou d’intervention et une collecte de données avant et après l’intervention. Cette étude s’est déroulée dans l’Uttar Pradesh, Inde, en 2018-2019. Six grands établissements de santé publique ont participé à l’évaluation de l’étude de déploiement: trois centres d’intervention et trois centres témoins. Un ensemble de mesures de changement pour une amélioration de la qualité des soins de maternité centrés sur la personne a été présenté dans les établissements d’intervention. Au total, 1200 femmes ont participé à l’étude: 600 femmes pour l’étude de base et 600 femmes à la fin de l’expérience. La méthode des doubles différences est utilisée pour estimer l’impact du déploiement de ce panier de mesures de changement pour une amélioration de la qualité dans les sites d’interventions par rapport aux sites témoins, au début et à la fin du projet, à l’aide d’une échelle validée de soins de maternité centrés sur la personne. Sur une échelle de 100 points, une amélioration de 24,93 points a été observée dans les scores globaux des soins de maternité centrés sur la personne parmi les établissements d’intervention entre le début et la fin de la recherche (IC 95%: 22,29, 27,56). Pour les huit indicateurs des soins de maternité centrés sur la personne que visait l’ensemble de mesures de changement, les établissements d’intervention ont enregistré une amélioration de 33,86 points (IC 95%: 30,91, 36,81) par rapport aux établissements témoins pendant les des cycles de l’enquête. Les conclusions semblent indiquer que le déploiement d’un ensemble de mesures de changement des soins de maternité centrés sur la personne permet d’améliorer l’expérience des soins chez les femmes ainsi que les résultats secondaires, notamment la qualité clinique, les visites des infirmières et médecins et la diminution des problèmes pendant l’accouchement.

Resumen

La atención materna centrada en la persona (AMCP) de mala calidad causa retrasos en la prestación de servicios y resultados adversos para la salud de la madre y del recién nacido. Este estudio describe el impacto de difundir un Paquete de Cambio, es decir, intervenciones que otros establecimientos de salud habían piloteado anteriormente e identificado como exitosas, para mejorar la AMCP en establecimientos de salud pública en Uttar Pradesh, India. Se utilizó un diseño cuasiexperimental con establecimientos de intervención y control emparejados, y se realizó la recolección de datos antes y después. Este estudio se llevó a cabo en Uttar Pradesh, India, en 2018-2019. Seis importantes establecimientos de salud pública participaron en la evaluación del estudio de difusión: tres establecimientos de intervención y tres establecimientos de control. En los establecimientos de intervención se presentó el Paquete de Cambio para el MC (mejoramiento de calidad) para mejorar la AMCP. En total, 1200 mujeres participaron en el estudio: 600 mujeres en la línea base y 600 en la línea final. Se utilizaron estimadores de diferencias en diferencias para examinar el impacto de difundir un Paquete de Cambio de MC en los sitios de difusión vs. los sitios de control y en la línea base y línea final utilizando una escala de AMCP validada. En una escala de 100 puntos, se observó un mejoramiento de 24.93 puntos en los puntajes generales de AMCP entre los establecimientos de difusión comparados con los establecimientos de control desde la línea base hasta la línea final (IC del 95%: 22.29, 27.56). Para los ocho indicadores de AMCP objetivo del Paquete de Cambio, los establecimientos de difusión aumentaron en 33.86 puntos (IC del 95%: 30.91, 36.81) comparados con los establecimientos de control en las rondas de la encuesta. Los hallazgos indican que la difusión de un Paquete de Cambio de AMCP mejora las experiencias de las mujeres con la atención que reciben, así como los resultados secundarios, tales como la calidad clínica, las visitas de enfermeras y médicos y la disminución de problemas de prestación de servicios.

Background

While India has made steady progress in advancing maternal health objectives, the country’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) remains high. Between 2016 and 2018, the MMR in India declined from 130 to 113 deaths per 100,000 live births;Citation1 however, significant inequities across the country continue, with poorer states reporting higher MMRs. Uttar Pradesh (UP), the country’s most populous state, had an MMR of 197 per 100,000 live births, the second highest MMR of any state in India.Citation1 In 2017, the Government of India launched a wide-scale initiative to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality by improving the quality of care during the immediate and post-partum period.Citation2 The initiative focused specifically on providing Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) and positive birthing experiences; however, implementation challenges remain and it is unclear how the programme has impacted broader quality of maternal care and maternal health outcomes.Citation3 Inequities in the MMR are correlated to poor experiential quality of care. High rates of mistreatment during childbirth have been reported in Uttar Pradesh, including physical or verbal abuse, lack of provider availability, use of non-evidence-based birthing practices, and threats of violence.Citation4–7 Poor patient experiences are particularly common in large, public hospitals in Uttar Pradesh, reflective of poor public health infrastructure and an overburdened health system.Citation8 Specific intervention strategies to improve women’s experiences during maternity care are needed.

Developed in 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) framework on Quality of Care for Maternity Care highlights person-centred maternity care (PCMC) as an important outcome for women globally.Citation9 PCMC is defined as being respectful of and responsive to women’s preferences and needs. It seeks to improve women’s experiences of care by facilitating collaborative and informed decision-making, ensuring freedom from abuse, coercion, and bribery, and providing a supportive environment for childbirth and labour.Citation10,Citation11 PCMC is linked to improved outcomes for both mothers and babies such as lower reported newborn complications and increased intention to return to the same facility for future births.Citation12 Despite recognition that women often experience high levels of mistreatment during maternity care, a recent systematic review of PCMC interventions found few that improved it. Of the interventions included in the review, there were mixed results on their effectiveness at improving PCMC.Citation13 Challenges to implementing PCMC include staff shortages and frequent staff turnover, high patient volumes, and lack of space in health facilities.Citation14,Citation15 Given high reported levels of mistreatment within facilities, and an increase in facility-based births in Uttar Pradesh, India, evidence-based quality improvement strategies are needed.

Quality Improvement Collaboratives (QICs) are an established method designed to enhance the impact of quality improvement (QI) tools, such as the Model for Improvement,Citation16 by bringing multi-disciplinary teams from similar organisations or systems together to focus on a common problem. They have been used to improve health care practices around the globe.Citation17 This approach has gained popularity due to its ability to make rapid improvements in low-resource settings, emphasis on improving patient care using existing resources, and a focus on organisational and institutional change.Citation17 Team work and cooperation across organisational boundaries may be effective for improving PCMC, given that other studies have found key facilitators for improving patient-centred care rest in part on the engagement, motivation, and collaboration of providers in effecting system change.Citation18 However, to our knowledge, QICs have not been applied to issues of women’s experiences of care. QICs are often resource-intensive as they are designed and led by experts external to the facilities involved.Citation18 Consequently, implementers often combine a QIC with the planned and active “spread” of learning to facilitate cost-effective uptake of successful improvement changes to a much wider set of recipients.

The spread model is defined as the replication of ideas and changes in processes or behaviours already shown to help secure improvements through a QIC, allowing impact at a much greater scale.Citation19 The spread model is different from the QIC model, however, because it requires less intensive external support from QI experts. Multiple options for spreading improvement interventions exist.Citation20 Implementers typically opt for a low resource-intensive approach requiring limited support from external experts. Although there are specific examples of effective applications of spread strategies to replicate QICs at scale,Citation21 these are limited and more research is needed to examine their efficacy in the area of PCMC. This present study examines a spread approach subsequent to a QIC to improve PCMC in maternity in public facilities in Uttar Pradesh.

To our knowledge, no studies have examined whether implementation and spread of a Change Package can generate improvements in PCMC. This paper will examine whether this approach is a viable mechanism to improve PCMC.

Methods

Facility selection

This study includes six public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh that had previously participated in an unrelated, clinically-focused, large-scale maternal health QI intervention.Citation22 Given this previous experience, it was assumed that the six study sites would be well-positioned to participate in activities described within this paper. Study facilities were located in two districts within 100 km of the capital of Uttar Pradesh and ranged from primary to community health centres. Three spread and three control facilities were matched based on levels of care (primary or community) and annual delivery load within the facility.

Intervention description and Change Package intervention

The initial QIC ran for 10.5 months in three public facilities in Uttar Pradesh, with results described in detail elsewhere.Citation23 Data from the initial QIC is not shown in this present study; however, the three public facilities in the initial QIC are located in the same districts as the facilities in this study, and comparable in level of care and annual delivery loads. The QIC team developed, tested, and refined a “Change Package”, a suite of interventions to improve PCMC indicators. Change Package interventions included a range of behavioural and process strategies that showed a positive impact on specific aspects of PCMC. Change Package interventions specifically addressed issues related to PCMC; examples include trainings and putting up posters for staff to introduce themselves, senior staff members working with cleaners to discuss roles and expectations around health facility cleanliness, providing curtains around beds to protect patient privacy and confidentiality, developing a script for explaining certain medicines or drugs given during and after labour and delivery, and training providers/staff to ask about women’s pain levels. For a more detailed list, see . The Change Package included detailed descriptions of the successful changes, any adaptations made by intervention facilities, and focused on improving a set of very targeted processes that were being poorly performed in both the intervention and control facilities prior to the intervention.

Table 1. Examples of successful change package interventions for Person-centred Maternity Care (PCMC)

Following the QIC, the Change Package interventions were implemented in three additional “spread facilities”. Spread facilities were encouraged to adopt the Change Package by senior district leaders and adoption was supported by an external QI practitioner who had in-depth knowledge of the interventions and their efficacy.

Implementing the spread model and Change Package (six months)

The present study assesses the impact on PCMC scores of spreading the Change Package interventions within health facilities with limited external support. Of the six total study sites, three facilities were selected as “spread sites” for the Change Package, and were asked to form “spread teams”, a group within the health facility that would oversee the implementation of the Change Package interventions. Over a six-month period, spread sites were guided to implement the Change Package interventions. An external QI practitioner conducted supportive coaching visits to the spread sites, starting with bi-monthly visits and progressively decreasing numbers of monthly visits by the end of the spread phase. The control facilities received no contact from the QI practitioner over this period; however, following the conclusion of the study, the study team presented successful Change Package interventions for the control facilities to implement if desired.

Data collection procedures and study sample

Baseline surveys were conducted between April and June of 2018 across the three spread (n = 300) and three matched control facilities (n = 300). Endline surveys were conducted between April and June of 2019 in the same facilities, with 300 women in each arm (n = 600 total). We ran a sample size calculation to detect a 10% difference in PCMC scores across sites with 95% confidence and alpha of 0.05. The difference was greater than 10% and we obtained our initial targeted sample size.

Female enumerators were trained in PCMC principles, research ethics, and best practices for data collection prior to deployment to the field. Within study facilities, enumerators approached women between 18 and 49 that had delivered a baby in the health facility within the previous seven days to determine their interest and eligibility to participate in the study. Women that agreed to participate provided verbal consent. Women who were not well enough to participate or who refused to participate following an explanation of the study were excluded. Surveys were conducted with women in semi-private locations within the facility to ensure confidentiality; limited space within the facilities did not allow for surveys to be conducted in fully private settings such as an office. Enumerators used a tablet-based guide to conduct the survey, which took approximately 45 min to complete. All data was uploaded to a main server at the end of each day and the Research Manager reviewed each entry to ensure data quality.

Study measures

Outcome variable: total PCMC score and Change Package PCMC score

Person-centred maternity care (PCMC) was measured by the PCMC scale, which comprises 27 items about care received over three domains: dignity and respect (6 items); communication and autonomy (9 items); and supportive care (12 items). The PCMC scale was developed in India, Kenya, and Ghana and has demonstrated high content, construct, and criterion validity and good internal-consistency reliability.Citation24 Individual items asked about specific types of person-centred care received and scores ranged from 0 to 3 (0 “No, never”; 1 “Yes, a few times”; 2 “Yes, most of the time”; 3 “Yes, all of the time”). Items reported as “not applicable” were conservatively recoded to receive the highest score. Total PCMC scores were computed by summing all PCMC items for each participant, ranging from 0 to 81 points. Final total PCMC and subdomain scores were scaled to 100-point scales.

Additionally, we investigated the eight targeted PCMC indicators that comprised the Change Package that were worked on by all spread facilities. In this manuscript, we refer to these indicators as “Change Package PCMC score”. The eight indicators that make up the Change Package PCMC score included the following indicators: (1) provider introduction; (2) assurance of visual privacy during exams; (3) ability to labour and deliver in the woman’s position of choice; (4) explanation of medicines and procedures; (5) provision of pain medication; (6) cleanliness of toilets/washrooms; (7) cleanliness of the post-natal ward; and (8) assisting the recently delivered woman to the toilet. Total scores for each participant summed all items and could range from 0 to 24 points. To assist with interpretability, the eight specific PCMC indicators were also scaled to 100-point scales.

We investigated the impact of the intervention on other outcomes including clinical quality, delivery complications (yes vs. no), and frequency of doctor and nurse visits while in the maternity ward (number of visits per day). Clinical quality was measured by a clinical quality index constructed from 22 items from the WHO’s standards of care for maternal and newborn care,Citation25 including blood pressure checks, heartbeat measurement, and vaginal exam, among others (yes vs. no). Possible scores for the index ranged from 0 to 22 and “don’t know” responses were recoded as “no”. We tested the reliability of these 22 items and the alpha coefficient was 0.86, suggesting high internal consistency.

Covariates

We explored socioeconomic factors, pregnancy and provider characteristics that may be associated with PCMC and other outcomes. We investigated distributions of age, parity, employment, wealth, religion, caste, literacy, education, number of antenatal care visits, pregnancy complications, facility type, as well as type and gender of delivery assistant by treatment group and survey round. Wealth quintiles were constructed using a modified EquityTool based on India NFHS4 (released 30 March 2019).

Analysis

We conducted three sets of analyses to assess the impact of the spread intervention (1) total PCMC scores for intervention vs. control facilities, (2) Change Package PCMC scores that were worked on during the intervention vs. control facilities, and (3) sub-domains of the total PCMC for intervention vs. control facilities. Differences between treatment groups at each phase were assessed by cross-tabulations, chi-square tests, and t-tests. We constructed multivariate regression difference-in-differences models for each set of analyses to evaluate the impact of the intervention on various outcomes including main effects terms for survey round and treatment group and an interaction term to indicate the difference between groups over time. Linear regression was used for analyses of PCMC, clinical quality, and frequency of doctor and nurse visits. Logistic regression was used to assess the odds of delivery complications. We tested for homogeneity of variance and used robust standard errors (Eicker-Huber-White) to correct for homoschedasticity and clustering. Final multivariate models adjusted for age, parity, education, wealth, religion, caste, facility type, delivery provider, number of ANC visits, and pregnancy complications. Stata SE 15.1 was used for all analyses and statistical significance was established at an alpha level of 0.05.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco under approval number 15-18008. Formative research for this study was approved from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Public Health Foundation of India (TRC-IEC-276/15). Designated approval was received from Population Services International (OHRB Federal wide Assurance (FWA) #0009154).

Results

Demographic characteristics

Participants at spread sites had greater wealth and higher education than those at control facilities (). More participants at control facilities had pregnancy complications than those at spread facilities at baseline, but a reverse trend was observed at endline. Across time, deliveries assisted by Anganwadi workers and ASHAs (community health workers) increased in spread and control facilities. Nurse- and physician-assisted deliveries decreased at spread facilities but increased at control facilities between survey rounds.

Table 2. Characteristics of participants, by spread/control and survey round

Impact of the intervention: total PCMC score, Change Package PCMC score, and PCMC sub-domains

Out of a 100-point scale, unadjusted overall mean PCMC score in spread facilities increased from 59.49 (SD 11.40) at baseline to 86.58 (SD 9.78) at endline. Mean PCMC score at control facilities was actually higher than spread at baseline, 65.84 (SD 9.24), but decreased to 62.35 (SD 12.20) at endline. The Change Package PCMC score increased between survey rounds in spread facilities from 42.71 (SD 16.15) to 83.36 (SD 13.51), and also in control facilities from 45.92 (SD 10.79) to 52.74 (SD 13.97) ().

Table 3. Mean total PCMC and subdomain scores, by spread/control and survey roundTable Footnotea

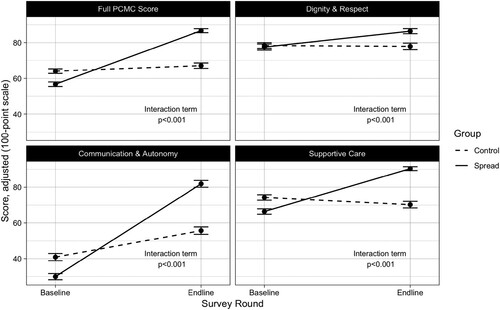

Adjusting for demographic characteristics, facility type, provider factors, and pregnancy complications, the mean total PCMC and subdomain scores increased at spread facilities compared to control facilities over time ().

Figure 1. Mean adjusted PCMC scores, by survey round and spread/control sites

Note: Scores were scaled to a 100-point scale. All estimates adjusted for age, parity, education, wealth, religion, caste, facility type, delivery provider, ANC visits, and pregnancy complications. Robust standard errors were used

Compared to control facilities, the spread facilities’ adjusted total PCMC scores increased an average of 27.14 points (95% CI: 24.41, 29.88) (). For the Change Package PCMC score, spread facilities increased 33.86 points (95% CI: 30.91, 36.81) relative to control facilities across survey rounds. The adjusted R2 for the total PCMC adjusted regressions was 0.605 compared to the Change Package PCMC score adjusted R2 value of 0.725. Both are statistically significant.

Table 4. Difference-in-differences analyses to assess the impact of spread on PCMC scores (total and change package)

Out of a 100-point scale, the clinical quality index increased by 3.10 points (95% CI: 1.96, 4.24) at spread facilities relative to controls over time (). Across time, odds of delivery complications at intervention facilities were 85% lower (95% CI: 58%, 95%) compared to controls. Regarding frequency of provider visits, the intervention group observed an increase of 1.8 additional nurse visits per day (95% CI: 1.5, 2.2) and 0.74 additional physician visits per day (95% CI: 0.56, 0.92) compared to controls across time.

Table 5. Difference-in-differences analyses to assess the impact of the Spread intervention on other outcomes

Discussion

Our findings show that a Change Package can be successfully spread to other public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh to generate improvements in PCMC. In addition to improving PCMC, the study also shows improvements in other outcomes within the spread facilities, including improved clinical quality, lower delivery complications, and greater frequency of doctor and nurse visits compared to control facilities. These findings align with previous research that demonstrates higher PCMC is associated with improved clinical outcomes.Citation8,Citation12

Out of a 100-point scale, we found that there was a 27-point improvement in overall PCMC score among spread facilities compared to control facilities during the study. The improvement was slightly higher when assessing only the Change Package PCMC indicators, with an increase of almost 34 points relative to control facilities across survey rounds. Our results indicate that the spread intervention explained 60.5% of the variance in total PCMC score, but explained 72.0% of the variance in the Change Package PCMC indicators alone. This is aligned with our expectations: we foresaw larger increases in the Change Package PCMC indicators than in other indicators within the PCMC Scale. These indicators were targeted specifically for improvement because they started at lower levels, indicating the need to focus on these indicators; additionally, because they started at lower levels, they had greater potential for absolute changes in improvements. More intense QIC approaches also demonstrate significant improvements in specific PCMC indicators as well as broader patient experience.Citation26

Because the overall PCMC score also significantly increased by 27 points, this indicates that improvements were made in many aspects of person-centred care, well beyond the indicators and behaviours that were targeted by the QI intervention. This “halo” effect indicates that improvements in targeted aspects of patient experience may have led to changes in non-targeted aspects of patient experience, either because positive experiences in targeted areas of care left patients better disposed to appreciate non-targeted areas of care, or because when providers changed the way they approach and treat patients in some areas of care, this changed approach also influenced and improved other aspects of care that they provided. These findings are significant given other large-scale clinical quality improvement initiatives in Uttar Pradesh that find that high costs and sustained investments are critical to ensuring changes in clinical and non-clinical staff practices.Citation27 This study provides evidence that a light-touch, spread approach may improve outcomes beyond PCMC outcomes if appropriate strategies are identified in similar facilities.

Our findings indicate that PCMC can be improved in public hospitals without an intensive QIC once a set of successful targeted interventions have been identified and aggregated as a Change Package. Spreading a Change Package to improve PCMC that has been developed within a context-specific QIC represents a cost-efficient model to move towards scale in a resource-constrained setting. This is especially relevant for public health systems in LMICs, where financial resources are often scant and staffing numbers severely disproportionate to the patient load,Citation14 making participation in time-intensive interventions especially burdensome.

This study has a number of limitations. First, there were a relatively small number of facilities in each arm; however, we made a concerted effort to include matched control facilities based on existing facility information. Second, all the facilities had also previously been part of a major quality of care initiative focused on improving clinical quality for delivery through use of a validated childbirth checklist.Citation22 It is plausible that these facilities are not reflective of facilities that may have lower levels of clinical quality of care. Additionally, a government-sponsored, national campaign to improve the cleanliness of public facilities may have influenced results in PCMC indicators focused on cleanliness of the washrooms and post-natal wards across both arms. Related, the Government of India, and the local government in Uttar Pradesh in particular, have launched wide-scale efforts to improve the clinical and experiential quality of care in labour rooms and maternity hospitals through a programme called LaQshya (Labour Room Quality Improvement Initiative).Citation2 Previous research highlights that active and consistent leadership support is critical to sustain and spread QI efforts.Citation28–30 It is unclear whether similar, positive results would have been observed if the government had not been primed or motivated to improve clinical quality and respectful maternity care. On the other hand, this also suggests that this type of spread strategy may be particularly timely and may be most effective at this time given national health priorities focused on improving maternal and newborn outcomes. Third, there may have been a Hawthorne effect, whereby facility staff may have changed their behaviour due to knowledge that the intervention was focused on patient experiences of care and that the study would measure this outcome through patient surveys. However, we would expect that control and spread facilities would both experience this phenomenon.

Conclusions

PCMC and respectful maternity care has gained global attention in the past few years, with the recognition that interventions are needed to improve maternal health outcomes. India is primed to lead these efforts given recent national attention to this issue and the government commitment to improving maternal health quality.Citation2 This study demonstrates that minimal QI facilitation in addition to the introduction of a Change Package developed within a similar context can improve women’s overall experiences of care. Future studies could explore the sustainability of effect from a QIC with a spread component to improve PCMC. Other studies where the spread design introduces successful changes across much larger areas of the health system would build further knowledge of cost-effectiveness. Progress in improving women’s quality of care is needed, and this study gives evidence for a cost-effective approach to potentially accelerate those efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the Quality Improvement teams in all facilities that participated in this study, as well as their facility leadership. We would especially like to thank the women that participated in the surveys for their time and candour. We thank the National Health Mission (NHM) of Uttar Pradesh for their collaboration and continued support of this study. Finally, we would like to thank the SPARQ team at UCSF for their assistance in data collection and implementation activities. MS conceived of and co-designed the intervention, developed study tools, led analysis and interpretation of the data, and led development and drafting of the manuscript. KG co-designed the intervention, led the process for acquisition of data, and supported interpretation of analysis. MN conducted analysis and interpreted the data. KPR, ABS and KS substantially facilitated acquisition of the data. DM co-designed the intervention, supported acquisition of the data, and supported interpretation of analysis. CG designed the intervention and supported interpretation of analysis. All authors contributed to, read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Office of the Registrar General, India. Special bulletin on maternal mortality in India 2016–18; 2020.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. LaQshya: press information bureau [Internet]. India: Government of India; 2019. [cited 2019 Dec 6]. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=191585

- Srivastava A, Singh D, Montagu D, et al. Putting women at the center: a review of Indian policy to address person-centered care in maternal and newborn health, family planning and abortion. BMC Public Health. 2017;18(1):20. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4575-2

- Diamond-Smith N, Sudhinaraset M, Melo J, et al. The relationship between women’s experiences of mistreatment at facilities during childbirth, types of support received and person providing the support in Lucknow, India. Midwifery. 2016;40:114–123. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.06.014

- Sudhinaraset M, Treleaven E, Melo J, et al. Women’s status and experiences of mistreatment during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh: a mixed methods study using cultural health capital theory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):332. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1124-4

- Dey A, Shakya HB, Chandurkar D, et al. Discordance in self-report and observation data on mistreatment of women by providers during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh, India. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):149. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0409-z

- Raj A, Dey A, Boyce S, et al. Associations between mistreatment by a provider during childbirth and maternal health complications in Uttar Pradesh, India. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(9):1821–1833. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2298-8

- Montagu D, Landrian A, Kumar V, et al. Patient-experience during delivery in public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India. Health Policy Plan. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz125

- Tunçalp Ö, Were W, MacLennan C, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;122(8):1045–1049. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13451

- Sudhinaraset M, Afulani P, Diamond-Smith N, et al. Advancing a conceptual model to improve maternal health quality: the person-centered care framework for reproductive health equity. Gates Open Res. 2017;1:1. DOI:https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.12756.1

- Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Golub G, et al. Development of a tool to measure person-centered maternity care in developing settings: validation in a rural and urban Kenyan population. Reprod Health. 2017;14. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0381-7

- Sudhinaraset M, Landrian A, Afulani PA, et al. Association between person-centered maternity care and newborn complications in Kenya. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12978

- Rubashkin N, Warnock R, Diamond-Smith N. A systematic review of person-centered care interventions to improve quality of facility-based delivery. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):169. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0588-2

- Giessler K, Seefeld A, Montagu D, et al. Perspectives on implementing a quality improvement collaborative to improve person-centered care for maternal and reproductive health in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa130

- Sudhinaraset M, Giessler K, Golub G, et al. Providers and women’s perspectives on person-centered maternity care: a mixed methods study in Kenya. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):83. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0980-8

- Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, et al. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. Wiley; 2009.

- ØVretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P, et al. Quality collaboratives: lessons from research. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(4):345–351. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.11.4.345

- Luxford K, Safran DG, Delbanco T. Promoting patient-centered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in healthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(5):510–515. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzr024

- Twum-Danso NAY, Akanlu GB, Osafo E, et al. A nationwide quality improvement project to accelerate Ghana’s progress toward millennium development goal four: design and implementation progress. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(6):601–611. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzs060

- Massoud M, Donohue K, Mccannon CJ. Options for large-scale spread of simple, high impact interventions. USAID Health Care Improvement Project: University Research Co. LLC (URC); 2010.

- Slaghuis SS, Strating MMH, Bal RA, et al. A measurement instrument for spread of quality improvement in healthcare. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(2):125–131. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzt016

- Semrau KEA, Hirschhorn LR, Marx Delaney M, et al. Outcomes of a coaching-based WHO safe childbirth checklist program in India. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(24):2313–2324. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1701075

- Montagu D, Giessler K, Kao Nakphong M, et al. Results of a person-centered maternal health quality improvement intervention in Uttar Pradesh, India; 2019.

- Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Phillips B, et al. Validation of the person-centered maternity care scale in India. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):147. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0591-7

- World Health Organization. Standards for reporting quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/advisory-groups/quality-of-care/standards-for-improving-quality-of-maternal-and-newborn-care-in-health-facilities.pdf?sfvrsn=3b364d8_2

- Montagu D, Giessler K, Nakphong MK, et al. A comparison of intensive vs. light-touch quality improvement interventions for maternal health in Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1121. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05960-6

- Barnhart DA, Spiegelman D, Zigler CM, et al. Coaching intensity, adherence to essential birth practices, and health outcomes in the BetterBirth Trial in Uttar Pradesh, India. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2020;8(1):38–54. DOI:https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00317

- Abela-Dimech F, Johnston K. Safe searches: the scale and spread of a quality improvement project. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2017;33(5):247–254. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000385

- Cranley LA, Hoben M, Yeung J, et al. SCOPEOUT: sustainability and spread of quality improvement activities in long-term care – a mixed methods approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):174. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2978-0

- Verma JY, Amar C, Sibbald S, et al. Improving care for advanced COPD through practice change: experiences of participation in a Canadian spread collaborative. Chron Respir Dis. 2018;15(1):5–18. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972317712720