Abstract

Irrespective of the legal status of abortion, access to abortion services for women is fraught with numerous challenges across the world. A recent study in India found that most women who had an abortion sought care outside an authorised facility or from a less qualified provider. An analysis of women’s experiences in seeking abortion services would provide a better understanding of the underlying reasons. This paper is based on a qualitative study of the experiences of 16 married women from rural Tamil Nadu, India. The in-depth interviews focused on their pregnancy and childbirth experiences and access to abortion services. The study highlights the obstacle course that women seeking to terminate an unwanted pregnancy have to traverse. Many women were not aware of the legal status of abortion, and frontline workers discouraged them and gave misleading information. The pathways to seeking an abortion were more complex for women from marginalised communities. Providers were judgemental and used delaying tactics or denied abortion services. For the less privileged women, abortion services from government health facilities were conditional on the acceptance of female sterilisation. The providers’ attitudes in government and private health facilities were disrespectful of the women seeking abortion services. To uphold the reproductive and human rights of women who seek abortion services, we need accessible and publicly funded health care services that respect the dignity of all women, are empathetic and uphold women’s right to safe abortion services.

Résumé

Quel que soit le statut juridique de l’avortement, l’accès des femmes aux services d’interruption de grossesse comporte de nombreuses embûches dans le monde. Une récente étude en Inde a révélé que la plupart des femmes ayant avorté avaient demandé des soins en dehors d’un centre agréé ou auprès d’un prestataire peu qualifié. Une analyse de l’expérience des femmes dans la demande de services d’avortement permettrait de mieux comprendre les raisons sous-jacentes de ce phénomène. Cet article est fondé sur une étude qualitative des expériences de 16 femmes mariées originaires du Tamil Nadu, Inde. Les entretiens approfondis se sont centrés sur leur expérience de la grossesse et de la naissance, ainsi que de l’accès aux services d’avortement. L’étude met en lumière la course d’obstacles que doivent entreprendre les femmes souhaitant interrompre une grossesse non désirée. Beaucoup de femmes ne connaissaient pas le statut juridique de l’avortement et les agents de première ligne les ont découragées et leur ont donné des informations fallacieuses. Les parcours pour demander un avortement étaient plus complexes pour les femmes issues de communautés marginalisées. Les prestataires étaient moralisateurs, avaient recours à des manœuvres dilatoires ou refusaient d’assurer les services d’avortement. Pour les femmes les moins privilégiées, les services d’avortement dans les centres de santé publics étaient subordonnés à leur acceptation de la stérilisation. Les comportements des prestataires dans les centres de santé privés et publics étaient irrespectueux des femmes demandant des services d’avortement. Pour faire appliquer les droits humains et reproductifs des femmes qui souhaitent avorter, nous avons besoin de services de soins de santé accessibles et financés par les fonds publics, qui respectent la dignité de toutes les femmes, soient empathiques et défendent le droit des femmes à des services d’avortement sans risque.

Resumen

Independientemente de la legalidad del aborto, el acceso de las mujeres a los servicios de aborto está plagado de numerosos retos en todo el mundo. Un reciente estudio en India encontró que la mayoría de las mujeres que habían tenido un aborto buscaron el servicio fuera de un establecimiento de salud autorizado o por medio de un prestador de servicios menos calificado. Un análisis de las experiencias de las mujeres que buscan servicios de aborto facilitaría entender mejor las razones subyacentes. Este artículo se basa en un estudio cualitativo de las experiencias de 16 mujeres casadas que vivían en zonas rurales de Tamil Nadu, en India. Las entrevistas a profundidad se enfocaron en sus experiencias de embarazo y parto y en su acceso a los servicios de aborto. El estudio destaca los obstáculos que enfrentan las mujeres que buscan interrumpir un embarazo no deseado. Muchas mujeres no eran conscientes del estado legal del aborto, y los trabajadores de primera línea las disuadieron y les dieron información engañosa. Las vías para buscar un aborto eran más complejas para las mujeres en comunidades marginadas. Los prestadores de servicios eran prejuiciosos y utilizaban tácticas para retrasar o negar los servicios de aborto. En el caso de las mujeres menos privilegiadas, los servicios de aborto proporcionados en establecimientos de salud del gobierno estaban supeditados a la aceptación de la esterilización femenina. Las actitudes de los prestadores de servicios en establecimientos de salud gubernamentales y privados eran irrespetuosas de las mujeres que buscaban servicios de aborto. Para que las mujeres que buscan servicios de aborto puedan ejercer sus derechos reproductivos y humanos, se necesitan servicios de salud accesibles, financiados con fondos públicos, que respeten la dignidad de todas las mujeres, sean empáticos y defiendan el derecho de las mujeres a obtener servicios de aborto seguro.

Introduction

From a human rights perspective, every woman should be guaranteed the right to access quality abortion services with dignity.Citation1–5 However, across the world women face numerous challenges in accessing abortion services. Studies show that marginalised women experience long delays, repeated visits or denial in publicly funded abortion facilities.Citation6,Citation7 Women from low-income groups with limited education, those living in remote areas, and adolescent, single, separated or divorced women also face challenges accessing abortion.Citation8–10 Marginalised women are often denied timely abortion services by institutional actors who cite gestational age and other health conditions as reasons.Citation6,Citation7,Citation9,Citation11

Further, normative, logistical and bureaucratic contexts in publicly funded institutions also force these women to continue with their unwanted pregnancies.Citation6,Citation7,Citation9–14 Consequently, women have to go through several hardships, such as raising financial resources to seek abortion in faraway places, or depend on the services of unsafe providers.Citation9,Citation11,Citation12 Such practices impact their health and accentuate their socio-economic vulnerabilities.Citation8,Citation9,Citation13,Citation14

In 1971, India enacted the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act for a broad range of grounds up to 20 weeks of gestation. In 2003, an amendment to the MTP rules allowed certified providers to provide medical abortion (MA) up to seven weeks gestation. Despite the legal status of abortion in India, access to safe abortion has several barriers and challenges.Citation15–18 A study covering six states in India shows that of the 15.6 million abortions in 2015, only 22% were obtained from health facilities. For 73% of women, abortion was performed using medication, outside the health facilities.Citation17 In India, negative attitudes and resistance or callous treatment meted out by healthcare providers from state-run institutions act as barriers to safe abortion access.Citation15,Citation19–21 The vulnerability and marginalisation of women accessing abortion in India are very similar to other country contexts.Citation15,Citation22–25 While accessing abortion services, women experience provider abuse, and denial due to poor health conditions or gestational age.Citation15,Citation19–22,Citation26 For these reasons, women either self-administer abortion pills or seek the services of unqualified providers.Citation26–29 Access to abortion for women from historically excluded and oppressed communities is even more challenging due to their socio-economic vulnerabilities. Given this backdrop, women are forced to seek abortion from private facilities,Citation24,Citation27–29 even in a state like Tamil Nadu, which has a relatively robust public health system.Citation30

This paper captures the lived experiences of married women from rural Tamil Nadu in India, with specific reference to their experiences with terminating an unwanted pregnancy. Unwanted pregnancy in the context of this paper is a pregnancy that either occurred when the woman did not want to have any more pregnancies or was mistimed. The study does not include unwanted pregnancies in the context of fetal anomaly and sex-selective abortion. As Mallik points out, sex-selective abortion is “not the result of unintended or unwanted pregnancy. It is a gendered preference for a certain type of pregnancy that guides the decision to undergo sex-selective abortion”.Citation31 In this study, the author has therefore attempted to distinguish unwanted pregnancies from pregnancies ending in sex-selective abortions. This study attempts to locate unwanted pregnancy and abortion-seeking experiences of married women within the context of their everyday lives and women’s agency. The study demonstrates the restricted and exclusionary nature of abortion services offered by healthcare providers. It further analyses the impact of these exclusionary practices on the health and wellbeing of women who are already constrained by everyday patriarchal forces operating in their private sphere. By exploring the life stories of women at the margins, this paper examines alternative pathways that could enable women to access safe abortion services.

Methodology

In this study, the author has adopted a phenomenological approach to examine the lived experiences of women, using a qualitative research method with a specific focus on understanding the sexual and reproductive health contexts of 16 married women hailing from one of the blocks (sub-district) in the Thanjavur district of Tamil Nadu, India. Although the research focused on the abortion experience, the study positioned itself on the continuum of married women’s sexual and reproductive experiences. The participants in the study were selected using a purposive, referral-based, and respondent-driven strategy. The criteria for inclusion were that the participant was a married woman who had experienced at least one induced abortion for reasons other than fetal anomaly and sex selection.

The snowball sampling technique was used to identify participants for the study. Village Health Nurses (VHNs), who are trained auxiliary nurse-midwives working as frontline/ community health workers in the government health system at the block level, helped to identify the women participants. VHNs were briefed on the purpose of the study and the criteria for selecting study respondents. The VHNs contacted potential respondents and informed them about the study. They then provided a list of women interested in participating in the research who had agreed to an initial meeting.

In-depth interviews were used as the primary method of data collection. An interview guide based on key themes encompassing the continuum of reproductive health aspects, from menarche up to recent reproductive health experience, formed the basis of data collection. Each of these themes focused on the individual experiences of the woman. Fieldwork for data collection was conducted from mid-April 2015 till October 2016. The interviews were carried out in the local language, Tamil, and were conducted across multiple sessions suiting the respondent’s availability. The average duration of each session was around two hours.

The participants offered their written informed consent for the interview and audio-recording. The interviews were conducted at a suitable and comfortable place for the participants, ensuring privacy to speak openly. The participants’ identities and institutions mentioned during the interviews are anonymised, and names are masked with pseudonyms to protect their identity. The data for this paper come from work done as part of doctoral research. The Doctoral Advisory Committee constituted by the Institution Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Mumbai) provided the ethical clearance (DSO/PhD/2015, 19 October 2015) to conduct the study as per the institutional norms.

The author’s positionality was that if a pregnant woman believes that she cannot continue her pregnancy, this has to be respected, and her situated knowledge has to be recognised. Such a standpoint also enabled the study participants to gradually trust the author as a woman and to share their personal stories and lived experiences. Further, her status as a “married woman” and “mother” of two children also provided the comfort space for the participants to share conversations with her on intimacy, care, sexual and reproductive health experiences. Such a relationship of trust and care evolved over time. The author also believes that her skills as a feminist qualitative researcher who was empathetic to the women’s life struggles, listened to their narratives, and respected their aspirations helped earn her the status of a “trusted” insider.

Each of the recorded interviews was transcribed from Tamil to English in a word document. Later these interviews were coded (thematically and pattern-wise) using the ATLAS. Ti V6 software. The initial coding aimed at understanding emerging themes, and the subsequent re-reading of transcripts helped derive the detailed codes and sub-themes within each central theme.

Results

Situating the study participants and their vulnerabilities

There were sixteen participants in the study. In terms of religion, all women participants were practising Hindus from different caste groups. Eight women belonged to less privileged caste groups, comprising Scheduled Caste (SC) and Most Backward Caste (MBC) categories. The rest belonged to General and Backward Caste categories. In terms of caste hierarchy and the historicity of their social positions, the latter groups were privileged compared to the former. The situated nature of women’s everyday lives is relevant to understand their varied experiences and the nature of fear, stress and embarrassment that women undergo when faced with an unwanted pregnancy. The intersectional social positions of women in terms of their gender, caste and class interfaces have a bearing on the nature of their abortion-seeking experiences. presents some of the demographic, reproductive characteristics of participants. Additionally, participants’ life situations have been described in order to locate their narratives in women’s lived experiences.

Table 1. Participant’s profile and context

Privileged caste groups from upper castes (General Caste) had access to better income-earning opportunities. They could afford a better standard of living than the less privileged caste groups, given their educational qualifications and occupational engagements. Though belonging to privileged caste groups, some participants were homemakers, did not have access to any source of earned income, and therefore were dependent on their husbands’ earnings. In cases where their husbands had neither a secure job nor a steady source of income, they were economically disadvantaged, similarly to the less privileged women from SC and MBC communities. The vulnerabilities of women participants from less privileged castes such as SC were reinforced by other factors, such as multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes, women’s dependency on their husbands for spending, job insecurity, low wages, and alcoholism among men in these families, which added to the everyday struggles of these women. While there was only one adverse pregnancy outcome in the privileged caste women, five women experienced adverse pregnancy outcomes among the less privileged caste women, three of them more than once. Further, the stories of less privileged women reveal that it is an accepted patriarchal norm for men to have sexual and marital relationships with more than one woman at a time. According to the respondents, men from less privileged caste groups also subjected their wives to sexual and domestic violence.

Women from privileged caste groups, even if employed and income-earning, did not have suitable decision-making spaces. Their agency was constrained when it came to matters such as contraception. The vulnerabilities of privileged caste women worsened when they crossed caste boundaries via marriage to someone from a different caste. Conversations with privileged and less privileged women revealed that none had the sexual autonomy to negotiate sexual relations and decision making with their husbands. Experience of societal and institutional discrimination is yet another factor common among the less privileged, especially from the lowest caste hierarchies. One woman from a historically stigmatised nomadic tribal community experienced discrimination by providers in the healthcare system. Such experiences of exclusion and marginalisation have forced women in this particular community to avoid seeking institutionalised health care.Citation32

The following section elaborates in detail the abortion care pathways chosen by the women participants of the study.

Abortion care pathways

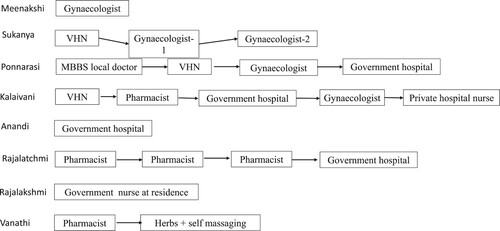

Women choose different pathways when confronted with an unwanted pregnancy. Most women facing an unwanted pregnancy for the first time try home remedies such as eating papaya and other food items with the hope of getting their periods. Eventually, when none of these measures meet with any success, they adopt diverse pathways for seeking an abortion. For instance, first-time abortion-seeking women from the marginalised SC communities approach the VHN or ask their husbands to buy abortion pills from the pharmacy. Except for Rajalatchmi, all the women depended on their husbands to procure the pills from the pharmacist to induce abortion. Vanathi, from the nomadic tribe, obtained MA pills from the pharmacy; these failed, and she self-induced abortion using hand massaging and herbs. However, when such strategies fail to deliver the intended results, these women are forced to pursue various other pathways, as described in .

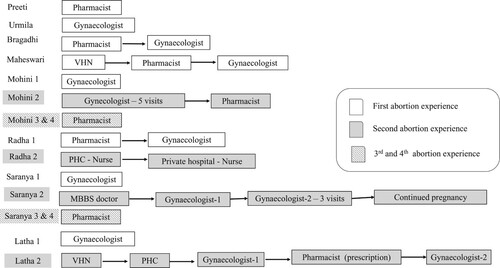

As depicted in , Rajalakshmi had approached a nurse who provided abortion services (unofficially) at her residence. A close relative mediated between Rajalakshmi and the nurse to set up the appointment. It is common knowledge among women in the study area that some nurses employed in the public or private health care institutions provided abortion services, unofficially, but at a cost. Due to her better financial position and her own disability as a reason for abortion, Meenakshi was able to access abortion services from a gynaecologist and pay for it. Similarly, Anandi went to the hospital with abdominal pain and eventually realised she was pregnant and underwent abortion, followed by sterilisation for preventing future births. For women from less privileged social and financial backgrounds, getting an abortion often did not end with a single visit to a provider, but ranged from two to five attempts to get the abortion done successfully. Women sought alternative providers because of persistent refusals/denials to provide abortion or cost factors. Among women from less privileged castes, none experienced a second-time abortion, except Meenakshi.

Quite differently, women from privileged financial and social backgrounds tended to approach the obstetrician-gynaecologist with far fewer attempts before they could terminate an unwanted pregnancy, as depicted in . Being a doctor, Preeti self-managed a medical abortion. For Bragadhi, the self-managed abortion led to excessive bleeding. She fainted and was admitted to a hospital, where a gynaecologist performed a dilatation and curettage (D&C). Maheswari, who wanted to have an abortion without her family members’ knowledge, approached the VHN first, then the pharmacist, and then a gynaecologist. However, access to safe abortion for Mohini, Radha, Saranya and Latha, who were second-time abortion seekers, became more difficult as they were in a difficult financial situation. The providers mistreated Saranya and Latha because they sought a second abortion. Some women (Saranya and Mohini) from the privileged castes who had gained some experience in abortion-seeking later approached the local private pharmacist directly when they sought an abortion for the third and fourth time.

Providers emerge as the key actors in the abortion-seeking pathway and their behaviour and attitudes towards abortion and abortion-seeking are described in the following section.

First point of contact: Village Health Nurses (VHN)

Most of the study participants had a general impression that abortion is illegal and not provided at the government hospital. Nevertheless, women looked for some guidance or support and approached the VHN when they faced an unwanted pregnancy for the first time. The functional role of the VHN is to visit the community to provide preventive maternal and child health care and family planning services. For six women in the study, their first contact was the VHN. When participants decided not to continue their pregnancy and approached the VHN for help, many women found that she was against abortion-seeking or was reluctant to help. Kalaivani, from a marginalised community and mother of two children, says,

“Over the phone, I told the Akka (VHN) that I did not want to continue the pregnancy. She was busy in the immunisation camp and scolded me in a loud tone, ‘Wait till I see you! Then only you will know what I am going to do to you!’ … But she never called me back.”

“I told the nurse (VHN) I did not want this child because my mother is sick, and no-one is there to take care of me. She said, ‘do not have an abortion or anything; why do you have to do all that?’ She suggested that I deliver the child and then undergo sterilisation or use Copper-T. I think this is what she says to every woman and often scolds them if they talk about abortion.”

Some VHNs used delaying tactics instead of outright denial. Maheswari’s pregnancy occurred due to the failure of the IUCD that was inserted immediately post-childbirth at the government hospital, and she wanted to terminate it right away. She says,

“My periods were delayed by 5–6 days. When the VHN came to the AnganwadiFootnote† I expressed my fear that I could be pregnant. Since my daughter is six months old and breastfeeding, I told her [the VHN] I did not want to continue [with the pregnancy]. First, she asked me to wait for ten days to confirm the pregnancy. Then she asked me to take vitamin tablets for five days and some pineapple as well. She kept on assuring me that my periods are delayed. Then she delayed my pregnancy test. By that time, I realised that she was not truly helpful and was using delaying tactics. Already 60–70 days had passed by then.”

“abortion is not allowed except if there is a fetal anomaly. Doctors should not do abortions for those getting pregnant without the permission of the husband. But they still do it in the private clinics”.

Pharmacist – the private provider

As seen in , some of the respondents decided to take abortion pills obtained from a pharmacist before exploring other pathways. Men who supported their wives’ decision to abort procured pills from the local pharmacist to induce abortion. In some cases, the pharmacist asked them to buy a pregnancy kit to confirm the pregnancy. Others provided the pills upon request with minimal instructions on their usage. Interestingly, the attitude of the pharmacists changed if the women approached them directly without the mediation by their husbands; in that case, they tended to behave rudely or sarcastically with them.

Latha described experiencing intra-uterine growth retardation at 18 weeks of pregnancy and was advised medical abortion by the doctor. Latha approached the pharmacist and gave the prescription. However,

“The pharmacist said, ‘only if your husband comes and signs, we will give the medicine’. I told him that the doctor wrote it. Still, he said, ‘even though the doctor has given this, according to our rules, we cannot give it’. Then I called my husband. But, he asked me to come home.”

Seeking abortion at a government health facility

A shared negative perception prevailed among the women from the less privileged social and economic backgrounds about the government hospital and its services, especially the tertiary hospitals. While some experienced it firsthand during their childbirth, some witnessed it when it happened to others. Rajalakshmi shared why she did not visit the government hospital for abortion:

“They speak to us without any dignity and in a dirty manner at the government hospital. They scold us. When a woman is in labour pain, the nurses there would say, ‘aren’t you a woman? Why are you shouting? When you lay with your husband, did it not hurt then?’ … We feel awkward and embarrassed. Sometimes they keep a post-delivery woman naked outside the ward. I am terrified to go there. Also, in the government [hospital], they are careless. But in private clinics, at least they will look at the problem and address it.”

“I was waiting in the queue to consult the lady doctor. She was examining a young woman [who was probably seeking an abortion]. I had never seen this young woman before, but it seemed that her husband was an alcoholic. Without even minding our presence, the doctor began to shout at the young lady, ‘Don’t you know what your family situation is? About the addiction of your husband? About your health condition? Yet you desire these pleasures, isn’t it?’ … It was so undignified and embarrassing to be scolded so in front of other women. I always recollect this incident and wonder what she would have told me if she knew about my situation?”

“I pleaded to the doctor to do an abortion. I cried, pleaded and begged, ‘My husband had left me knowing I am pregnant … to get married to another woman … I do not have anyone else. Will you please do an abortion? I can’t raise the children alone, and I am just a casual labourer, and there is no one else to support me.’ The doctor said that I have to stay there for ten days for observation. It [my pregnancy] was only 48 days then. They kept tablets in my vagina, and it did not come out. Then they gave oral pills every alternate day; it still did not happen. Each tablet cost Rs. 500 [US$ 6.7]. One day the senior lady doctor came for rounds and began to comment in a very undignified manner, ‘You would go and lie down to evannukko (some man), and is it our job to do abortion for you?’ In a blunt, curt tone, she said, ‘better get operated [female sterilisation]. If we do an abortion, you will go to some other person and become pregnant again. Do you think that the government hospital is for all these things? If you want to do family planning along with the abortion, then tell us’ … I felt ashamed and embarrassed at the words of that senior doctor … that too in front of everyone else! Therefore I agreed to undergo the [sterilisation] operation. The doctor’s words reminded me of my mother-in-law’s words, ‘you have conceived from some other guy (evannukko) and are now saying it is my son’s child and asking to put my son’s surname for your child?’. Then the doctor abused me with my caste identity, remarking, ‘your caste people always do this, and so on’. One’s life becomes even more miserable when we hear all those hurtful words.”

Apart from these experiences that shape women’s perceptions towards the services of government healthcare providers, there are factors such as continuous denial of family planning services when desired that demotivate women to access government facilities. The experiences of Ponnarasi illustrate this. Ponnarasi hails from a less privileged social and economic background and had experienced seven pregnancies, including adverse birth outcomes. She had approached the government hospital for an abortion during her eighth pregnancy.

“Ever since my third delivery, my mother and I had been asking them to do the operation [family planning]. They would always deny saying that I don’t have enough blood. I already have five living children, and this time the abortion pills that my husband got from the pharmacy failed. I told my husband that I couldn’t bear any more children, and he somehow managed to get me admitted to the government hospital. They agreed to do the abortion only if we accepted their demand to undergo the family planning operation. I was admitted to the hospital only after my husband signed and agreed to sterilisation. I was there for 20 days due to complications, but somehow I got my abortion and operation done.”

Abortion in the private sector

Women who did not want to undergo permanent family planning procedures approached private healthcare facilities for abortion. The preference for private healthcare facilities is because of the widespread perception and many women’s experiences that the government provides abortion services only to those women who agree to undergo sterilisation. While some women consulted qualified medical professionals, others sought the services from nurses, who are not legally permitted to conduct abortions. The strategy of women participants from privileged social and economic backgrounds was to consult qualified private providers directly, without much apprehension. However, these women have also faced unique experiences due to diverse contextual factors.

Urmila, accompanied by her friend, consulted the doctor whose treatment had helped her conceive her previous child. Urmila says,

“I told the doctor that there is no one to care for the existing child, and I can’t quit my job given my husband’s low income. So, I have decided to abort. She understood and gave me the medical abortion pills.”

“the doctor initially scolded me that I should have been careful. Later, she asked to get admitted and then did a D&C.”

“I briefed Dr J about how I took abortion pills that were provided by Dr J’s hospital staff two months ago, and even then, I had not got my periods. After examining me, the doctor replied, ‘I do not think it got cleaned completely. It seems that you are three months pregnant now. Why are you taking these [abortion] pills? You should not take these pills. Instead of suffering like this, why don’t you do family planning?’ (Loud voice). Then the doctor asked, ‘are you going to deliver?’ and added, ‘if you are going to deliver, first do a scan and see how the baby is’. I replied that I did not want this pregnancy and requested her to abort it. The doctor replied that it would cost Rs.2500 [US$ 34]. As I could not arrange that large an amount, I approached the nurse in the same hospital two days later. She carried out the abortion at a much lower price.”

Some of the study participants also had to face such moral dilemmas when they sought the services of private health care providers. Saranya shared how she decided to continue an unwanted pregnancy after much effort to abort.

“I tried eating papaya when my periods were delayed by just two days. But nothing happened. A week later, we [with husband] visited a doctor in this locality. She said papaya seeds work as abortifacient and sent me back. Then we consulted another lady doctor [gynaecologist] who had retired from government service. She had carried out my previous abortion. She scolded us and questioned why we wanted to abort. She denied an abortion, saying that the fetus was in good health. Then we visited Dr K [obstetrician-gynaecologist], who owns a hospital in the town. During the first consultation, she told us that it would cost Rs. 8000 [US $108]. We visited again after two days, and she said I would require a blood transfusion and, therefore, it will cost an extra sum of Rs. 2000. After three days, when we went with the money, she said it would cost an additional sum of Rs. 30,000 because the pregnancy had advanced, and I would need surgery for abortion. She kept on insisting that ‘the foetus is a life, and your girl baby [the elder child] is also a life. Would we kill the elder child?’ The way she made those remarks made me feel terrible, and I became scared of the surgery. I decided to continue that pregnancy even though my health was weak, and my elder girl was just seven months old. The abortion was very expensive too … .”

“I had visited the lady doctor (gynaecologist) at least five times and paid her the consultation fee every time. Initially, she convinced me to retain the pregnancy, saying that it is a boy. When I refused by saying that my family and economic situations are not good, she gave me vitamin tablets, a few small size tablets, and some vaginal tablets. Two months passed without any outcome. Finally, based on the information given by my sister-in-law, my husband got tablets from the pharmacy, and I terminated the pregnancy.”

Abortion by untrained providers

Circumstances such as failed MA attempts, abusive behaviour and denial by government providers, or delay and denial strategies by private providers, forced women to approach untrained and illegal abortion providers such as nurses. Nurses and other less qualified providers are preferred as they ask fewer questions and carry out the abortion at an affordable price. In the words of a Rajalakshmi,

“My aunt knew a nurse at the government hospital. She was the one who performed the abortion at the nurse’s quarters located within the government hospital. I gave Rs. 700. She inserted a vaginal tablet and when the bleeding started, cleaned it with a ‘koradu’ [a semblance of a plier] and then gave medicines for three days.”

“I already had two daughters and did not wish for any more children. But, at the government hospital, they denied an abortion and asked me to continue with the pregnancy. And then, Sister K who works in the same hospital, said she could do it at some other place and demanded 2000 rupees. Then I decided to go to Chennai and get it done in a private clinic near my sister’s place. There were 2–3 nurses and one male person, and one of the nurses did the abortion. They also spoke properly. Unlike Sister K, they conducted the abortion and placed a copper-T after that for Rs.1500. Sorrandara mathiri irundhucchu [I felt like they were scraping]. Then they gave tablets for a week.”

“She asked me to lie down, keep my knees lifted and expanded. She inserted a Kambi [rod kind of a tool] inside my vagina and did something. I could not tolerate that pain, it was so excruciating, and I made a loud sound. I told her it is very painful. The nurse, in a casual and mocking tone, said, ‘What is this? Why are you shouting so much for this? College-going young girls come here, and all they want is to get cleaned, and they immediately walk out. They neatly lie down and get it done and walk out so coolly. [In a harsh tone, she continued] Don’t have sex for one month. Otherwise, the child will stick back in your stomach, and you will have to come back again to me and go through this!’ … The nurse continued with this painful scraping for almost 15 minutes. I experienced severe pain. And then she gave tablets for 5–6 days. For one week, there was bleeding. After a four-day gap, the bleeding resumed for two more days.”

Discussion

In India, abortion is legal for many indications, yet women are often driven to seek abortion outside authorised facilities. Previous studies have described the diverse barriers that marginalised women face while seeking abortion.Citation1–7, Citation9, Citation21 The present study highlights the obstacle course of women in Tamil Nadu seeking to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. First, many women are not aware of the legal status of abortion. Second, the frontline workers discourage them and give misleading information. Women in this study interpreted the VHNs’ negative attitudes, delaying tactics and denial of abortion as equivalent to the absence of public abortion services. Although all public sector facilities at the primary health care (PHC) and higher levels could provide induced abortion,Citation33 conversations with the study participants and follow-up discussions with the VHNs suggested that only tertiary level government health facilities did so. When doctors fail to act in accordance with the law on the legitimate grounds for abortion, this also creates an impression among women that abortion is illegal. A behavioural change communication campaign over two years conducted in Bihar and Jharkhand found substantial improvement in the knowledge on the legal status of abortion and where to obtain services.Citation34 The perception of legal status can affect care-seeking behaviour and the ability to choose safe, legal providers.

In the absence of information on the legal grounds for abortion, accessing a pharmacist is one of the pathways chosen by some women. Here, the pharmacists need mediation by husbands and act as gatekeepers of women’s morality. When husbands are supportive of the abortion, the pharmacist plays a crucial role as a provider of abortion services. The decision making and provisioning agents are both men. The pharmacists’ insensitive, rude behaviour towards women who approached them directly is not just about gender barriers but also violates the rights of women. Such practices challenge the debates on expanding the reproductive rights of women and their autonomy.

It may be noted that the self-administration of MA pills is widespread across the country. The pathways of seeking care during unsuccessful attempts are also documented.Citation28 Medical abortion pills are highly acceptable to women, and many reach out soon after recognising a delay in their regular menstrual cycle.Citation29,Citation35 Women sometimes learn about MA pills before or after approaching a formal or informal provider. This study adds to current evidence that women who tried to self-manage using the medications obtained from pharmacies lacked proper guidance and information on what to expect.Citation36 Studies in India suggest poor quality of care when pharmacists dispense MA pills and do not provide information on MA pills and their side effects.Citation35,Citation37,Citation38 Another recent study found that intermediaries such as the VHN and the pharmacist appear at multiple points in the women’s abortion trajectories and act as barriers or facilitators in accessing abortion.Citation39

Though legal restrictions prevail, women’s agency to self-manage abortion with pills has to be considered a paradigm shift.Citation40 At the same time, we need to recognise the complexities that women face while seeking external help for abortion.Citation41 In this regard, actors such as feminist practitioners and feminist and rights-based non-governmental organisations could play an important role in securing and protecting vulnerable and marginalised women’s sexual and reproductive rights. These actors could play a crucial role in providing safe and effective methods to terminate unwanted pregnancies, such as information support services, counselling and medical abortion pills.Citation40–43

This paper reinforces the position that the government should ensure the easy availability and accessibility of MA pills through the public health system at the PHC level.Citation28,Citation44,Citation45 Availability of MA pills in PHC centres will enable women to receive the appropriate information, medication and ready access to safe abortion. It also appears that many nurses and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (the equivalent of VHNs in this study) are already providing abortion services to women in rural areas. Based on expert recommendations,Citation46 this paper suggests that it is crucial to expand the provider base for comprehensive abortion care services with suitable training and certification of midlevel providers in the health sector.

The client-provider interaction determines the quality of care in service-delivery systems.Citation47 It also acts as a critical component in the client’s access to the right to information and to make an informed choice. A 2007 study in India documented that the quality of client-provider interaction and the client’s perception of the respectfulness of providers were key to choosing the provider for abortion.Citation20 In our study, the providers’ attitudes were disrespectful towards clients in public as well as many private health facilities. The experiences of women who hail from less privileged social and economic backgrounds in this study demonstrate that public health facilities make abortion services conditional on acceptance of female sterilisation. Conversations with private sector doctors and women’s narratives point out that private providers are also judgemental, and the delaying tactics and denial of abortion do not respect the legal provisions of the MTP Act. In the context of the United States, Petchesky and Banes have documented historical narratives where abortion discourses have their roots in the public health understanding of fertility regulation, and moral and religious norms governing sexuality and sin.Citation12,Citation48,Citation49 Providers try to passively indoctrinate women with a fetal-centric (healthy fetus, “it appears to be a boy”) message and concept of sin in the hope that the women will continue the pregnancy. These are symbolical tactics that are largely shaped by patriarchal and moral predicaments.Citation12,Citation48 Providers exercise their power to decide who should be provided with an abortion and who is denied, irrespective of what the MTP Act says. The consequence is that they make the woman feel guilty for a long time. Several studies point out the impact that denial of abortion has on women to their health, wellbeing, family and relationships, such as anxiety symptoms, low self-esteem, lower life satisfaction and depression.Citation3,Citation15,Citation50–52

In addition, the behaviour of providers towards women seeking abortion suggests their profound alienation from the social realities of women. Many healthcare providers fail to recognise or empathise with women’s lack of autonomy in sexual relations and the use of contraception within the patriarchal social norms governing women’s lives.Citation49 Providers’ unsympathetic attitudes led women to make multiple provider visits amidst their already vulnerable situations, and spend unnecessarily towards failed abortion attempts.

Conclusion

It is after jumping through many hoops, undergoing a lot of stress, and often experiencing humiliation and conditionalities such as sterilisation, that many women in India obtain an abortion. India’s National Health Policy 2017 envisages the attainment of the highest possible level of health and wellbeing without anyone having to face financial hardship, due to good quality health care services.Citation53 The findings of this study are far from the goals of India’s policy commitment. In 2018, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare updated the Comprehensive Abortion Care (CAC) Guidelines to assist doctors and programme managers in the country’s effective delivery of abortion services.Citation33 The CAC guidelines clearly emphasise women-centred care, which would allow women to choose their method of abortion and post-abortion contraception, make available services close to home and guarantee high quality of care. It appears that government functionaries at the state level fail to ensure, in practice, comprehensive and dignified abortion care in public facilities. There is a visible disconnect within national and state policies, strategies, intent and ineffective implementation of abortion law.Citation33,Citation53,Citation54

As Malhotra et al. rightly put it, for many women in developing countries, “abortion is a choice that is derived from lack of alternatives”. Citation55 Women seeking abortion make choices based on their options and the autonomy they possess to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Non-consensual sex within marriage and sexual violence is known to be widely prevalent.Citation35 Evidence suggests that denial of abortion by providers inflicts a traumatic experience on women.Citation15 Therefore, the challenges women confront to get an abortion are not mere constraints. They represent the violation of a series of rights, such as the right to health, life, enjoyment of the benefits of scientific progress and its application, freedom from discrimination, and autonomy in reproductive decision-making, enshrined in various international treaties and instruments.Citation55

India has ratified its commitment to the UN Human Rights Committee, ICPD Programme of Action, and Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Considering India is accountable towards its commitments, the International Human Rights Standard asserts that States are obliged to protect human rights against violations by their representatives and against harmful acts by private persons or entities.Citation50,Citation56 Privatisation of health care inevitably presents the threat of commodification of health services, which many women from poor and marginalised social and economic backgrounds may not have access to. We need an affordable, accessible and humane public healthcare system. Such a system would respect women’s dignity, irrespective of gender, caste and class barriers. It would uphold women’s right to safe abortion services provided with empathy and understanding of the gendered structures that underlie unwanted pregnancies. Healthcare providers play a vital role in the equitable provision of abortion services. An enabling environment begins with a positive provider attitude of abortion as a component of women’s essential sexual and reproductive health services.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all my study participants. I am thankful to Dr. Asha Achuthan for her guidance in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

† Government centres that provide non-formal pre-school education and essential health care services such as nutrition, immunisation at the village level.

References

- Berer M. National laws and unsafe abortion: the parameters of change. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12(24):1–8. [cited 2021 May 2]. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3776110.

- Berer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: in search of decriminalisation. Health Hum Rights. 2017 Jun;19(1):13–27. PMID: 28630538; PMCID: PMC5473035.

- Corrêa S, Petchesky R. Reproductive and sexual rights: a feminist perspective. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva. 1995;6:147–177.

- World Health Organization. Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2nd ed. 2012. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70914/1/.

- Safe and legal abortion is a woman’s human right. Centre for Reproductive Rights, New York, 2004.

- Ostrach B. Publicly funded abortion and marginalised people’s experiences in Catalunya. Anthropol Action. 2020;27(1):24–34. [cited 2021 May 1]. Available from: https://www.berghahnjournals.com/view/journals/aia/27/1/aia270103.xml.

- Ostrach B. Did policy change work? Anthropol Action. 2014;21(3):20–30. [cited 2021 May 2]. Available from: https://www.berghahnjournals.com/view/journals/aia/21/3/aia210304.xml.

- Becker D, Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Juarez C, et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with obstacles to abortion care: findings from a survey of abortion patients in Mexico City. Womens Health Issues. 2011 May–Jun;21(3 Suppl):S16–S20. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.009. PMID: 21530832.

- Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA, Jones RK, et al. Denial of abortion because of provider gestational age limits in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014 Sep;104(9):1687–1694. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301378. Epub 2013 Aug 15. PMID: 23948000; PMCID: PMC4151926.

- de Moel-Mandel C, Shelley JM. The legal and non-legal barriers to abortion access in Australia: a review of the evidence. Eur J Contraception & Reprod Health Care. 2017. doi:10.1080/13625187.2016.1276162.

- Hajri S, Raifman S, Gerdts C, et al. “This is real misery”: experiences of women denied legal abortion in Tunisia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0145338), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145338.

- Shakya G, Kishore S, Bird C, et al. Abortion law reform in Nepal: women’s right to life and health. Reprod Health Matters. 2004 Nov;12(24 Suppl):75–84. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(04)24007-1. PMID: 15938160.

- Foster D, Steinberg J, Roberts S, et al. A comparison of depression and anxiety symptom trajectories between women who had an abortion and women denied one. Psychological Med. 2015;45(10):2073–2082. doi:10.1017/S0033291714003213.

- Jerman J, Frohwirth L, Kavanaugh ML, et al. Barriers to abortion care and their consequences for patients traveling for services: qualitative findings from two states. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017 Jun;49(2):95–102. doi:10.1363/psrh.12024. Epub 2017 Apr 10. PMID: 28394463; PMCID: PMC5953191.

- Bhate-Deosthali and Rege. Denial of safe abortion to survivors of rape in India. Health and Human Rights J. 2019;21(2):189–198. [cited 2021 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6927364/pdf/hhr-21-02-189.pdf.

- Sanneving L, Trygg N, Saxena D, et al. Inequity in India: the case of maternal and reproductive health. Glob Health Action. 2013 Apr 3;6:19145. doi:10.3402/gha.v6i0.19145. PMID: 23561028; PMCID: PMC3617912.

- Singh S, Shekhar C, Acharya R, et al. The incidence of abortion and unintended pregnancy in India, 2015. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Jan;6(1):e111–e120. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30453-9. Erratum in: Lancet Glob Health. 2017 Dec 12; PMID: 29241602; PMCID: PMC5953198.

- Jain D. Time to rethink criminalisation of abortion? Towards a gender justice approach. NUJS Law Rev. 2019;12(1):21–42.

- Pyne S, Ravindran TKS. Availability, utilisation, and health providers’ attitudes towards safe abortion services in public health facilities of a district in West Bengal, India. Women’s Health Reports, 1.1. 2020. doi: 10.1089/whr.2019.0007. Available from: http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/whr.2019.0007.

- Barua A, Apte H. Quality of abortion care: perspectives of clients and provides in Jharkhand. Econ Polit Wkly. 2007;42(48):71–80.

- Doran F, Nancarrow S. Barriers and facilitators of access to first-trimester abortion services for women in the developed world: a systematic review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(3):170–180.

- Sowmini CV. Delay in termination of pregnancy among unmarried adolescents and young women attending a tertiary hospital abortion clinic in Trivandrum, Kerala, India (May 2013). Reprod Health Matters. May 2013;21(41):243–250. Available from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2321064.

- Banerjee SK, Andersen K. Exploring the pathways of unsafe abortion in Madhya Pradesh, India. Glob Public Health. 2012;7(8):882–896. 10.1080/17441692.2012.702777.

- Sri SB, Ravindran TK. Safe, accessible medical abortion in a rural Tamil Nadu clinic, India, but what about sexual and reproductive rights? Reprod Health Matters. 2015 Feb;22(44 Suppl 1):134–143. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(14)43789-3.

- Elul B, Bracken H, Verma S, et al. Unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion in Rajasthan, India: a qualitative exploration. New Delhi: Population Council; 2004.

- Srivastava A, Saxena M, Percher J, et al. Pathways to seeking medication abortion care: a qualitative research in Uttar Pradesh, India. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0216738, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216738.

- Ramachandra L, Pelto PJ. Medical abortion in rural Tamil Nadu, South India: a quiet transformation. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13(26):54–64. ISSN 0968-8080. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26195-5.

- Varkey P, Balakrishna PP, Prasad JH, et al. The reality of unsafe abortion in a rural community in South India. Reprod Health Matters. 2000 Nov;8(16):83–91. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(00)90190-3. PMID: 11424254.

- Alagarajan M, Sundaram A, Hussain R, et al. Unintended pregnancy, abortion and postabortion care in Tamil Nadu – 2015. New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018, doi:10.1363/2018.30162.

- Parthasarathi R, Sinha SP. Towards a better health care delivery system: the Tamil Nadu model. Indian J Community Med. 2016 Oct–Dec;41(4):302–304. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.193344. PMCID: PMC5112973. PMID: 27890982.

- Mallik R. Sex selection: a gender-based preference for a pregnancy. Reprod Health Matters. 2002;10(19):189–190.

- Sunil B. Marginalisation and access to safe abortion. A case study on the struggles of a Narikuravar woman in Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu. eSSH. 2018;1(2):4–15. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332570861_Marginalisation_and_Access_to_Safe_Abortion_Bhuvaneswari_Sunil_4.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Comprehensive abortion care: training and service delivery guidelines. New Delhi: National Health Mission, 2018.

- Banerjee SK, Andersen KL, Warvadekar J, et al. Effectiveness of a behavior change communication intervention to improve knowledge and perceptions about abortion in Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013 Sep;39(3):142–151.

- Powell-Jackson T, Acharya R, Filippi V, et al. Delivering medical abortion at scale: a study of the retail market for medical abortion in Madhya Pradesh, India. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 30;10(3):e0120637, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120637. PMID: 25822656; PMCID: PMC4379109.

- Mishra A, Yadav A, Malik S, et al. Over the counter sale of drugs for medical abortion- knowledge, attitude, and practices of pharmacists of Delhi, India. Int J Pharmacol Res. 2016;6(3):92–96.

- Diamond-Smith N, Percher J, Saxena M, et al. Knowledge, provision of information and barriers to high quality medication abortion provision by pharmacists in Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Jul 11;19(1):476, doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4318-4. PMID: 31296200; PMCID: PMC6622002.

- Ganatra B, Manning V, Pallipamulla SP. Availability of medical abortion pills and the role of chemists: a study from Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2005 Nov;13(26):65–74. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26215-8. PMID: 16291487.

- Nandagiri R. Like a mother-daughter relationship: community health intermediaries’ knowledge of and attitudes to abortion in Karnataka, India. Soc Sci Med. 2019 Oct;239:112525, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112525. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31499333.

- Jelinska K, Yanow S. Putting abortion pills into women’s hands: realising the full potential of medical abortion. Contraception. 2018;97(2):86–89. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.05.019.

- Palma Manríquez I, Moreno Standen C, Álvarez Carimoney A, et al. Experience of clandestine use of medical abortion among university students in Chile: a qualitative study. Contraception. 2018;97(2):100–107. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.09.008.

- Tousaw E, Moo SNHG, Arnott G, et al. It is just like having a period with back pain: exploring women’s experiences with community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion on the Thailand-Burma border. Contraception. 2018;97(2):122–129. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.06.015.

- Zurbriggen R, Keefe-Oates B, Gerdts C. Accompaniment of second-trimester abortions: the model of the feminist Socorrista network of Argentina. Contraception. 2018;97(2):108–115.

- Moore AM, Stillman M, Shekhar C, et al. Provision of medical methods of abortion in facilities in India in 2015: a six-state comparison. Glob Public Health. 2019 Dec;14(12):1757–1769. doi:10.1080/17441692.2019.1642365. Epub 2019.

- Shekhar C, Sundaram A, Alagarajan M, et al. Providing quality abortion care: findings from a study of six states in India. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2020 Jun;24:100497, doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2020.100497. Epub 2020 Jan 30. PMID: 32036281.

- Expanding the provider base for abortion care. Findings and recommendations from an assessment of pre-service training needs and opportunities in India. 2013. Available from: https://www.ipas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/EPBINDE13-Access.

- Simmons R, Elias C. The study of client-provider interactions: a review of methodological issues. Stud Fam Plann. 1994 Jan-Feb;25(1):1–17. PMID: 8209391.

- Petchesky RP. Abortion and woman’s choice: the state, sexuality, and reproductive freedom. Boston: Northeastern University Press; 1984: 412.

- The Moral Veto: Framing Contraception, Abortion, and Cultural Pluralism in the United States. Burns. Gene: Books.

- DePiñeres T, Raifman S, Mora M, et al. “I felt the world crash down on me”: women’s experiences being denied legal abortion in Colombia. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):133, doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0391-5.

- Puri M, Vohra D, Gerdts C, et al. I need to terminate this pregnancy even if it will take my life: a qualitative study of the effect of being denied legal abortion on women’s lives in Nepal. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):85, doi:10.1186/s12905-015-0241-y.

- Biggs M, Upadhyay U, McCulloch C, et al. Women’s mental health and wellbeing five years after receiving or being denied an abortion: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;74(2):169–178.

- National Health Policy. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, India; 2017. [cited 2021 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/nhpfiles/national_health_policy_2017.pdf.

- Country profile on universal access to sexual and reproductive rights: India. [cited 2021 Jan 12]. Available from: https://arrow.org.my/publication/country-profile-on-universal-access-to-sexual-and-reproductive-rights-india/.

- Malhotra A, Nyblade L, Parasuraman S, et al. Realising reproductive choice and rights. Abortion and contraception in India. Washington, DC, USA: International Centre for Research on Women; 2003.

- Berer M. Making abortion a woman’s right worldwide. Reprod Health Matters. 2002 May;10(19):1–8. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(02)00010-1. PMID: 12369311.