Abstract

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and universal health coverage (UHC) are fundamental to health as a human right. One way that countries operationalise UHC is through the development of an essential package of health services (EPHS), which describes a list of clinical and public health services that a government aspires to provide for their population. This study reviews the contents of 46 countries’ EPHS against the standard of the Guttmacher-Lancet Report’s (GLR) nine essential SRHR interventions. The analysis is conducted in two steps; EPHS are first categorised according to the level of specificity of their contents using a case classification scheme, then the most detailed EPHS are mapped onto the GLR’s nine essential SRHR interventions. The results highlight the variations of EPHS and provide information on the inclusion of the GLR nine essential SRHR interventions in low- and lower-middle income countries’ EPHS. This study also proposes a case classification scheme as an analytical tool to conceptualise how EPHS fall along a spectrum of specificity and defines a set of keywords for evaluating the contents of policies against the standard of the GLR. These analytical tools and findings can be relevant for policymakers, researchers, and organisations involved in SRHR advocacy to better understand the variations in detail among countries’ EPHS and compare governments’ commitment to SRHR as a human right.

Résumé

La santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs (SDSR) ainsi que la couverture santé universelle (CSU) sont fondamentaux pour la santé en tant que droit humain. Les pays mettent la CSU en pratique de différentes façons, notamment en définissant un panier essentiel de services de santé, qui décrit une liste de services cliniques et de santé publique qu’un gouvernement aspire à fournir à sa population. Cette étude examine le contenu du panier essentiel de services de santé de 46 pays par rapport aux neuf interventions essentielles de SDSR du rapport de la Commission Guttmacher-Lancet. L’analyse est menée en deux étapes; les paniers essentiels sont d’abord classés selon le niveau de spécificité de leur contenu, à l’aide d’un mécanisme de classification des cas, puis les paniers les plus détaillés sont cartographiés selon les neuf interventions essentielles de SDSR du rapport de la Commission Guttmacher-Lancet. Les résultats mettent en lumière les variations des paniers essentiels de services de santé et renseignent sur l’inclusion des neuf interventions essentielles de SDSR du rapport de la Commission dans les paniers des pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire. Cette étude propose aussi un mécanisme de classement des cas comme outil analytique pour conceptualiser comment les paniers essentiels de services de santé sont répartis dans un spectre de spécificité et elle définit un ensemble de mots clés pour évaluer les contenus des politiques en fonction des normes du rapport de la Commission. Ces outils analytiques et ces conclusions peuvent être pertinents pour les décideurs, les chercheurs et les organisations actives dans le domaine de la santé et des droits sexuels et reproductifs, afin de mieux comprendre les variations entre les paniers essentiels de différents pays et comparer l’engagement des gouvernements en faveur de la santé sexuelle et reproductive comme droit humain.

Resumen

La salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SDSR) y la cobertura universal de salud (CUS) son fundamentales para la salud como derecho humano. Una manera en que los países operacionalizan la CUS es por medio de la creación del paquete básico de servicios de salud (PABSS), que describe una lista de los servicios clínicos y de salud pública que un gobierno aspira a ofrecer a su población. Este estudio revisa el contenido del PABSS de 46 países comparado con el estándar del Informe de Guttmacher-Lancet (GLR) de nueve intervenciones de SDSR esenciales. El análisis es realizado en dos etapas: primero se categorizan los PABSS según el nivel de especificidad de su contenido utilizando un esquema de clasificación de casos y después se mapean los PABSS más detallados en las nueve intervenciones de SDSR esenciales del GLR. Los resultados destacan las variaciones de PABSS y proporcionan información sobre la inclusión de las nueve intervenciones de SDSR esenciales del GLR en los PABSS de países de bajos y medianos bajos ingresos. Además, este estudio propone un esquema de clasificación de casos como herramienta analítica para conceptualizar cómo los PABSS se clasifican a lo largo del espectro de especificidad, y define una serie de palabras clave para evaluar el contenido de las políticas comparado con el estándar del GLR. Estas herramientas analíticas y hallazgos pueden ser pertinentes para formuladores de políticas, investigadores y organizaciones involucrados en abogar por SDSR, para que puedan entender mejor las variaciones en detalle entre los PABSS de los países y comparar el compromiso de los gobiernos con SDSR como derecho humano.

Introduction

In 2019, the UN General Assembly declared Universal Health Coverage (UHC) necessary for achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by 2030.Citation1 The same year, at the Nairobi Summit, the international community gathered to take stock of the unfinished business from the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action.Citation2 There countries re-committed to a forward-looking sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) agenda to achieve the SDGs,Citation3 including target 3.7, the achievement of universal access to sexual and reproductive health under UHC.Citation4 By reaffirming health as a human right, UHC aims to give everyone everywhere access to essential health services without undue financial hardship.Citation1,Citation5 While UHC remains a priority of the global community, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health systems globally, as countries work to simultaneously prioritise and maintain critical services, including essential sexual and reproductive health services.Citation6 The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the fact that all countries have finite resources, and therefore must decide what services to prioritise within their UHC reform.Citation7,Citation8

UHC and SRHR have been described as “mutually reinforcing”,Citation9 and SRHR is more frequently being recognised as a fundamental aspect of UHC.Citation3,Citation10 For countries working to operationalise UHC, an initial step is the development of an essential package of health services (EPHS),Citation11 particularly one which includes a holistic set of SRHR interventions.Citation8 The term EPHS describes “a list of clinical and public health services that a government has determined as priority for the country … (and) that the government is providing or aspiring to provide to its citizens in an equitable manner”.Citation12 The contents of an EPHS are designed to reflect the unique contexts which produce them.Citation13 Perhaps because of this, EPHS have been observed to vary widely in their level of detail and the specificity of their contents.Citation12,Citation13

Published in 2018, Accelerate progress – sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: the report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission (GLR), proposed a comprehensive definition of SRHR which goes beyond the ICPD definition to cover sexual rights and includes a package of nine essential interventions () selected to address the central aspects of SRHR.Citation14 These nine interventions have been described as “ … a benchmark to measure countries’ progress towards delivering an essential package of SRHR services”.Citation8 Furthermore, several of these SRHR interventions have been described as cost-effective, cost-saving, and inexpensive,Citation8,Citation14 suggesting that these interventions should form part of a set of investments for low-income countries (LICs) and lower-middle income countries (LMICs) who must meet the needs of growing populations on limited public health budgets.Citation8,Citation14,Citation15

Table 1. The Report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission's essential package of sexual and reproductive health interventions

Previous research has investigated the inclusion of different services within the contents of EPHS. Wright and HoltzCitation12 used the Partnership for Maternal, Child, and Newborn Health’s (PMNCH) priority reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) interventions as a framework to examine the inclusion of RMNCH interventions within 24 low- and lower-middle income countries’ EPHS. Later, a study published by the PMNCHCitation8 used the GLR’s nine essential SRHR interventions as a standard to investigate how six sub-Saharan African countries prioritised SRHR interventions within their EPHS. Based on reviews of existing literature however, no known research has examined the inclusion of essential SRHR interventions within a larger sample of countries’ EPHS.

This study analyses the extent to which the GLR’s nine essential SRHR interventions are currently included in the essential packages of health services of low- and lower-middle income countries. The analysis focuses on the content of 46 low- and lower-middle income countries’ EPHS to further the understanding of how countries are incorporating SRHR in their UHC reform.

Methods

Study design

This study reviews the contents of countries’ essential packages of health services using a two-step analysis. As it has been well established that the contents of EPHS vary,Citation7,Citation12,Citation13 the first step of the analysis categorises EPHS according to the level of detail of their contents using a case classification scheme. The second step analyses the contents of the EPHS which contain a list of clinical and public health services using a high-level matching. The high-level matching analysis was conducted by tagging EPHS using a set of keywords developed by the authors (Appendix 1). The two-step analysis was performed twice to improve the trustworthiness of the results.Citation16 Peer-debrief consultations with authors from similar studies were held to gain feedback on the analysis and increase its credibility.

Delimitations

While previous studies by Wright and HoltzCitation12 and the PMNCHCitation8 investigated the implementation and prioritisation processes of 24 and six countries’ EPHS, respectively, this study chose to focus solely on the explicit contents of countries’ EPHS in order to capture data from a larger study population (51 countries). Because the analysis is limited to the contents of countries’ EPHS this study cannot speak to the development processes behind countries’ EPHS or how countries are translating these policies into practice. Rather, this study identifies larger trends within contents of low- and lower-middle income countries’ EPHS, both in the level of detail of their contents, and the essential SRHR interventions they include. It is also important to recognise that, while EPHS are a commonly used tool to operationalise UHC,Citation11 they are but one way in which countries operationalise UHC and are not necessarily a comprehensive representation of countries’ work towards UHC, nor of how countries are integrating SRHR interventions into their UHC work.

Study population

Similar to a study by Stenberg et al.Citation15 we included all 31 countries classified as LICs and the 20 most populous LMICs in the study population. The study population was chosen as these countries face relatively large health burdens, challenges in resource mobilisation, and urgent needs in effective use of resources.Citation15 The World Bank Country and Lending GroupsCitation17 was used as a reference for countries’ income classification. The final study sample consisted of 46 countries as data from five countries could not be located.

Data collection

Data was collected in January and February of 2020 from publicly available policy documents which outlined countries’ EPHS. Countries’ EPHS go by many names, are not uniform, and can be found in a wide variety of documents. Most often EPHS were found in documents such as (but not limited to) health sector strategic plans, health development plans, and national health policies (Appendix 2). Documents were retrieved through exhaustive internet searches using Google and relevant government and health agency websites using iterations of the following search terms: “essential package of health services”, “essential health service package”, “minimum health package”, “basic health service package”, “national health service package”, “essential health benefits package”, “essential universal health coverage package” and “universal health coverage plan”. Documents were collected in English, French, Portuguese, and Ukrainian, with documents not in English translated using Google Translate.

The final study sample consisted of 47 documents from 46 countries; one document per country other than Afghanistan, whose EPHS was very clearly divided across two documents, which therefore were taken together and treated as one EPHS in the analysis. Priority was given to primary sources (i.e. government policy documents) and documents which included a list of clinical and public health services. In the cases where newer documents were alluded to but were not possible to retrieve, available older documents were selected for analysis. The collected documents were published between 2005 and 2018; only the documents from Egypt and Ukraine did not specify a publishing date. Of the collected documents, 30 specified a date range for the period of time they covered. For a comprehensive list of the documents used in the analysis, see Appendix 2.

First level of analysis: case classification

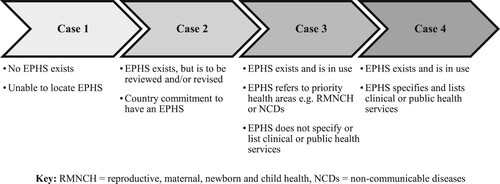

The first step of the analysis reviewed the contents of the collected EPHS to determine which were detailed enough for the second level of analysis. For the first level of analysis, a case classification scheme was developed (), which categorised EPHS into four different cases (Case 1–4) according to the level of detail of their contents.

Second level of analysis: the high-level matching

The second level of analysis, the high-level matching, was performed to identify the GLR nine essential SRHR interventions within the contents of countries’ EPHS. To be eligible for the second level of analysis, a country’s EPHS had to include a list of clinical and public health services and be classified as a Case 4 during the first level of analysis.

The high-level matching was conducted by tagging the contents of the EPHS using keywords, (see Appendix 1 for a comprehensive list of the keywords used). The keywords were developed using the GLR and related literatureCitation8,Citation14 and were designed to include services conceptually related to, and capture the essence of, each of the GLR’s essential SRHR interventions. For example, “family planning”, “contraceptive pills”, and “fe/male condoms” were among the keywords selected to identify interventions related to modern contraception (GLR 2).

It was sufficient for an EPHS to contain one keyword for the corresponding intervention to be marked as included. In cases where none of the corresponding keywords were present, an intervention was marked as excluded. All EPHS were analysed twice, and tags were double-checked to ensure that the results of the high-level matching were representative of the EPHS’ contents. An audit trail of the analysis was kept in the form of Excel spreadsheets.

As a final step a sensitivity test was performed by re-tagging the Case 4 EPHS with an alternative, more stringent, inclusion criteria for GLR 4, “Safe abortion services and treatment of complications of unsafe abortion”. The sensitivity test was performed to test how changes to the keywords affected the results. For the sensitivity test, the set of keywords for GLR 4 were modified, and only EPHS which contained the keywords “medical vacuum aspiration (MVA)”, “safe abortion” and/or “medical abortion” were marked as including GLR 4.

Results

Case classification

No EPHS were located for five countries (10%) and therefore these countries were categorised as having Case 1 EPHS. Seventeen countries’ (33%) EPHS were categorised as Case 2, and 12 countries’ (24%) EPHS were categorised as Case 3. Finally, 17 countries’ (33%) EPHS were categorised as Case 4. shows the results of the case classification disaggregated by country income status.

Table 2. Case Classification results disaggregated by country income status

The high-level matching

The Case 4 EPHS (n = 17) were eligible for the high-level matching as these included a list of clinical and public health services. This category comprised 10 LICs and seven LMICs; 36% of the population of LICs, and 39% of the population of LMICs, respectively. All Case 4 EPHS included interventions related to modern contraception (GLR 2), antenatal, childbirth, and postnatal care (GLR 3), and prevention and treatment of HIV and other STIs (GLR 5). The intervention most frequently missing from Case 4 countries’ EPHS was comprehensive sexuality education (GLR 1), which appeared in only six (35%) countries’ EPHS. Interventions related to sub- and infertility (GLR 8) and sexual health and wellbeing (GLR 9) were also frequently missing, each respectively included in only eight (47%) EPHS ().

Table 3. Inclusion of the Guttmacher-Lancet Report’s nine essential SRHR interventions within Case 4 essential packages of health services (EPHS) disaggregated by country income status and arranged from most to least interventions included

Bangladesh was the only country from the high-level matching which included all of the GLR’s nine essential SRHR interventions in their EPHS. India’s and Liberia’s EPHS included all interventions except for comprehensive sexuality education (GLR 1). Over half (53%) of the countries included seven or more interventions in their EPHS. The Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, North Korea, and The Republic of the Congo included the least number of interventions in their EPHS, with five out of nine interventions respectively. As such, all countries from the high-level matching included at least five of the GLR’s nine essential SRHR interventions in their EPHS. However, which interventions were included varied by country.

The results of the sensitivity test showed the number of Case 4 EPHS (n = 17) which included safe abortion services (GLR 4) dropped from 82% (n = 14) to 47% (n = 8) under the test’s modified set of keywords ().

Table 4. Results of the Sensitivity Analysis compared to the results of the High-Level Matching for safe abortion (GLR 4)

Discussion

Despite the fact that EPHS are widely defined as including a defined list of clinical and public health services,Citation7,Citation11,Citation12,Citation18 findings from this study show that most EPHS do not fit this definition. From the study population of 51 countries, 90% (n = 46) have an EPHS; however, most are not detailed enough to analyse which SRHR interventions they include. Only the Case 4 countries from the case classification, i.e. 33% (n = 17) of the collected EPHS, fit this definition and contained a list of clinical and public health services. Findings from the case classification highlight the discrepancy between theory and practice and demonstrate that, in reality, EPHS range from very specific and detailed to less specific and aspirational.

The relationship between the specificity and the value of EPHS has been discussed in different directions. However, the inclusion of a defined list of services is largely agreed to be an accountability issue, as this can inform citizens what services are available, and equally important, not available, to them under UHC policies.Citation7,Citation19 As countries work towards UHC, Glassman et al.Citation19 argue that the creation of an explicit health benefits package may help manage progress towards UHC, and that it is essential for creating a sustainable system of UHC. Others state that increases in the administrative detail within EPHS may increase the quality of servicesCitation20 and that “ … governments have a fundamental responsibility for ensuring universal access to an essential package of clinical services, with special attention to reaching the poor” [p.108].Citation18 On the other hand, Wright and HoltzCitation12 argue that EPHS often represent a broad policy statement, and WaddingtonCitation13 claims that EPHS are most useful when used as a political, rather than technical tool. Some also argue that EPHS should strike a middle ground in terms of level of detail.Citation21 Despite different positions on the relationship between the specificity and value of EPHS, findings from the case classification corroborate previous literature,Citation8,Citation12,Citation13,Citation21 providing evidence on the sizeable variations which exist among EPHS in terms of the level of detail of their contents.

As all countries are different, no single EPHS is appropriate for every country, just as there is no one path which countries must follow to achieve UHC.Citation8 Instead, EPHS are designed to reflect the context from which they are born as “countries vary with respect to disease burden, level of poverty and inequality, moral code, social preferences, operational challenges, [and] financial challenges”.Citation12 However, it has been noted that if countries’ prioritisation processes were based on gender- and equity-adjusted cost-effectiveness models using the best available evidence, SRHR interventions would naturally be included in countries’ EPHS across all contexts.Citation8

The results of the high-level matching show that despite countries’ commitments to UHCCitation1,Citation22 to health and SRHR as a human right,Citation2,Citation4,Citation23 and the availability of the GLR as a standard,Citation8,Citation14 the vast majority of countries’ EPHS do not include a comprehensive list of essential SRHR interventions. Bangladesh was the only country to include services related to all of the GLR nine essential SRHR interventions in their EPHS, something which previous research had not been able to identify.Citation8 That this study identified only one EPHS with a comprehensive list of essential SRHR interventions indicates that there is still much work to be done to integrate SRHR into UHC reform. Beyond the challenges of integrating essential SRHR services into UHC policies, previous research also highlights the challenges of translating policies around access to essential SRHR interventions to the implementation of services.Citation8

Results from the high-level matching also speak to larger trends in the inclusion of essential SRHR interventions across low- and lower-middle income countries (). The universal inclusion of services relating to contraception (GLR 2), maternal and newborn health (GLR 3), and HIV/AIDS (GLR 5), was consistent across all countries and reflects larger trends in prioritisation within the field of SRHR.Citation14 Other trends differed across country income groups; for example, comprehensive sexuality education (GLR 1) was the least common intervention among LICs, while information, counselling, and services for subfertility and infertility (GLR 8) was the least common intervention among LMICs. These results provide an overview of how essential SRHR interventions are currently included in specific countries’ EPHS.

To test the sensitivity of the results to the keywords, a sensitivity analysis was performed on safe abortion (GLR 4). Safe abortion (GLR 4) was chosen for the test as the language surrounding this intervention has been contentious historically. When required to include terminology explicitly related to abortion, i.e. “medical vacuum aspiration (MVA)” or “medical abortion”, the number of EPHS which included safe abortion (GLR 4) dropped from 82% (n = 14) to 47% (n = 8). These results, together with the study by the PMNCH,Citation8 demonstrate the importance of language to policy, the accountability issues which many countries face around access to safe abortion services, and the limitation of content analysis to tell the full story of what is on paper versus what is practiced in reality.

Finally, this study contributes a novel case classification scheme which conceptualises the varying level of detail among EPHS and illustrates how EPHS fall along a spectrum of specificity. Additionally, this study defines a set of keywords (Appendix 1) which are useful for evaluating policies against the benchmark of the GLR. Previously, evaluations of policies against the GLR were based on researchers’ interpretations of what each intervention covered. By putting forth a defined set of keywords for each of the GLR nine essential interventions, this study allows for more systematic policy evaluations. These analytical tools can be used by policymakers, researchers, and others involved in SRHR advocacy.

Limitations

The inclusion of an intervention within a country’s EPHS cannot tell us whether it is available or accessible at the point of service delivery. Conversely, services that are not included in an EPHS might still be available to those who need them. As the presence of a single keyword was considered sufficient for an intervention to be marked as included, the results of the high-level matching illustrate the minimum SRHR interventions which countries appear to have prioritised within a component of UHC reform. The collection of EPHS was limited to what was publicly available through online sources. Because many EPHS in the analysis pre-date the publication of the GLR in 2018, future iterations of countries’ EPHS may have different alignment with the GLR’s essential SRHR interventions.

Conclusions

Most countries have an EPHS, but most are not specific enough to allow for an analysis of what SRHR services governments offer, or aspire to provide, and the content ranges from vague to very specific. Results from the high-level matching illustrate that countries’ inclusion of SRHR interventions echo larger trends in prioritisation within the field of SRHR. However, despite countries’ commitments to UHC, to SRHR as a human right, and the availability of the GLR as a standard, a comprehensive set of essential SRHR interventions is not included in the vast majority of low- and lower-middle income countries’ EPHS.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge valuable input on methods and analysis from Eoghan Brady and Jeanna Holtz.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage (A/RES/74/2). New York; 2019.

- ICPD. Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population Development: 20th anniversary edition. Cairo: United Nations; 1994.

- UNFPA. Sexual and reproductive health and rights: an essential element of universal health coverage. New York; 2019.

- Nairobi Summit. Nairobi Statement on ICPD25: accelerating the promise. Nairobi: Nairobi Summit on ICPD25; 2019. [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.nairobisummiticpd.org/content/icpd25-commitments.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report: health systems financing the path to universal coverage. Geneva; 2010.

- Pillay Y, Manthalu G, Solange H, et al. Health benefit packages: moving from aspiration to action for improved access to quality SRHR through UHC reforms. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(2):1842152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1842152.

- Glassman A, Giedion U, Smith PC. In: Glassman A, Giedion U, Smith PC, editors. What’s in, what’s out? Designing benefits for universal health coverage. Washington (DC): Center for Global Development; 2017.

- PMNCH. Prioritizing essential packages of health services in six countries in sub-Saharan Africa; 2019.

- Ravindran TKS, Govender V. Sexual and reproductive health services in universal health coverage: a review of recent evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1779632.

- Appleford G, RamaRao S, Bellows B. The inclusion of sexual and reproductive health services within universal health care through intentional design. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(2):1799589. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1799589.

- Aman A, Gashumba D, Magaziner I, et al. Financing universal health coverage: four steps to go from aspiration to action. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):902–903. https://www.un.org/pga/73/2019/05/17/.

- Wright J, Holtz J. Essential health packages of health services in 24 countries: findings from a cross-country analysis. Bethesda: United States Agency for International Development (USAID); 2017.

- Waddington C. Essential health packages: what are they for? What do they change? London: HLSP Institute; 2013.

- Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress – sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher– Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2642–2692. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9.

- Stenberg K, Hanssen O, Edejer TT-T, et al. Financing transformative health systems towards achievement of the health sustainable development goals: a model for projected resource needs in 67 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(9):e875–e887. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30263-2.

- Dahlgren L, Emmelin M, Hällgren U, et al. Qualitative methodology for international public health. Umeå: Umeå University; 2019.

- World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups, World Bank; 2020. [cited 2020 Feb 1]. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- World Bank. World Development Report 1993, Investing in health. New York; 1993.

- Glassman A, Giedion U, Sakuma Y, et al. Defining a health benefits package: what are the necessary processes? Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(1):39–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2016.1124171.

- World Bank. World development report 1993: investing in health: background paper series: the essential packages of health services in developing countries. Oxford; 1994.

- Giedion U, Bitrán R, Tristao I. Inter-American development bank. Health benefit plans in Latin America: a regional comparison; 2014.

- United Nations. Sustainable development goals officially adopted by 193 countries, United Nations in China; no date. [cited 2020 Aug 12]. Available from: Sustainable Development Goals Officially Adopted by 193 Countries.

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 45th ed. New York; 2006.

Appendices

Appendix 1

GLR nine essential SRHR interventions and their corresponding keywords used for the high-level matching:

Comprehensive sexuality education

keywords: power, sexuality, gender equality, evidence-based education on sex, masculinity, femininity

Counselling and services for a range of modern contraceptives, with a defined minimum number and types of methods

keywords: family planning, sterilization, IUDs, hormonal implants, injection, contraceptive pills, fe/male condoms, modern fertility awareness, emergency contraceptive pill

Antenatal, childbirth, and postnatal care, including emergency obstetric and newborn care

keywords: antenatal, childbirth, postnatal, newborn, obstetric, emergency, pre-eclampsia, anemia, diabetes, congenital HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B

Safe abortion services and treatment of complications of unsafe abortion

keywords: abortion, medical abortion (abortion via drugs: mifepristone, misoprostol), manual vacuum aspiration, post-abortion case management

Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections

keywords: HIV, AIDS, PMTCT, STI, testing, prevention, treatment, pregnant women, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), antiretroviral therapy (ART), syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis

Prevention, detection, immediate services, and referrals for cases of sexual and gender-based violence

keywords: prevention, detection, counselling, referrals, sexual based violence, gender-based violence, intimate partner violence, child abuse/neglect, rape, sexual violation

Prevention, detection, and management of reproductive cancers, especially cervical cancer

keywords: cancer, prevention, detection, screening, management, treatment, palliative care, reproductive, cervical, breast, prostate, testicular, penile, HPV vaccine, Pap test, VIA (visual inspection with acetic acid),

Information, counselling, and services for subfertility and infertility

keywords: subfertility, infertility, secondary infertility, information, counselling, pregnancy

Information, counselling, and services for sexual health and wellbeing

keywords: information, counselling, services, sexuality, sexual identity, sexual relationships, psychosexual counselling, sexual dysfunction

Appendix 2

List of countries’ essential packages of health services used in the analysis:

Afghanistan: A Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan-2010/1389, (2010).

Afghanistan: The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan, (2005).

Angola: Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento Sanitário 2012–2025, (2012).

Bangladesh: Essential Package of Health Services Country Snapshot: Bangladesh, (2015).

Benin: Plan National de Développement Sanitaire 2018–2022, (2018).

Burkina Faso: Plan National De Développement Sanitaire 2011–2020, (2011).

Burundi: National Health Development Plan 2011–2015, (2011).

Cameroon: Health Sector Strategy 2016–2027, (2016).

Chad: Politique Nationale de Santé 2016–2030, (2016).

Côte d’Ivoire: Plan National de Developpement PND 2016–2020, (2016).

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Essential Package of Health Services Country Snapshot: Democratic Rep. of Congo, (2015).

Egypt: White Paper: Framing National Health Policy, Executive Summary, (n.d.).

Eritrea: Health Sector Strategic Development Plan HSSDP: 2010–2014, (2010).

Ethiopia: Essential Health Services Packages for Ethiopia, (2005).

The Gambia: National Health Policy 2012–2020, Republic of the Gambia, (2012).

Ghana: Essential Package of Health Services Country Snapshot: Ghana, (2015).

Guinea: Plan National de Développement Sanitaire (PNDS) 2015–2024, (2015).

Guinea-Bissau: Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento Sanitário II-PNDS II-2008–2017, (2008).

Haiti: Le Paquet Essentiel de Services, (2015).

India: Essential Package of Health Services Country Snapshot: India, (2015).

Indonesia: Essential Packages of Health Services Country Snapshot: Indonesia, (2015).

Kenya: Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSP) July 2014-June 2018, (2013).

Liberia: Essential Package of Health Services. Primary Care: The Community Health System Phase One, (2011).

Madagascar: Plan de Développement du Secteur Santé 2015–2019, (2015).

Malawi: Health Sector Strategic Plan II 2017–2022, (2017).

Mali: Plan Decennal de Developpement Sanitaire et Social (PDDSS) 2014–2023, (2014).

Mozambique: Health Sector Strategic Plan PESS 2014–2019, (2014).

Myanmar: Myanmar National Health Plan 2017–2021, (2016).

Nepal: Nepal Health Sector Strategy Implementation Plan 2016–2021, (2017).

Niger: Normes et Standards du Systeme de Sante du Niger, (2017).

Nigeria: Second National Strategic Health Development Plan 2018–2022, (2018).

North Korea: Medium Term Strategic Plan for the Development of the Health Sector DPR KOREA 2016–2020, (2017).

Philippines: National Objectives for Health 2017–2022, (2018).

Republic of the Congo: Plan National de Développement Sanitaire 2018–2022, (2018).

Rwanda: Health Services Packages for Public Health Facilities, (2017).

Sierra Leone: Sierra Leone Basic Package of Essential Health Services 2015–2020, (2015).

Somalia: Somali Roadmap Towards Universal Health Coverage 2019–23, (2018).

South Sudan: Package of Health and Nutrition in Secondary and Tertiary Health Care, (2011).

Sudan: National Health Sector Strategic Plan II (2012–16), (2012).

Tajikistan: National Health Strategy of the Republic of Tajikistan 2010–2020, (2010).

Tanzania: Health Sector Strategic Plan July 2015–June 2020, (2015).

Togo: Système de financement de la santé au Togo: Revue et analyse du système, (2015).

Uganda: Health Sector Development Plan 2015/16–2019/20, (2015).

Ukraine: Medical Guarantee Program: Implementation in Ukraine, (n.d.).

Uzbekistan: Uzbekistan Health Systems Review, (2014).

Vietnam: Plan for People’s Health Protection, Care and Promotion 2016–2020, (2016).

Zambia: Zambia National Health Strategic Plan 2017–2021, (2017).