Abstract

Men’s involvement in abortion is significant, intersecting across the individual, community and macro factors that shape abortion-related care pathways. This scoping review maps the evidence from low- and middle-income countries relating to male involvement in abortion trajectories. Five databases were searched, using search terms, to yield 7493 items published in English between 01.01.2010 and 20.12.2019. 37 items met the inclusion criteria for items relating to male involvement in women’s abortion trajectories and were synthesised using an abortion-related care-seeking framework. The majority of studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and were qualitative. Evidence indicated that male involvement was significant, shaping the ability for a woman or girl to disclose her pregnancy or abortion decision. Men as partners were particularly influential, controlling resources necessary for abortion access and providing or withdrawing support for abortions. Denial or rejection of paternity was a critical juncture in many women’s abortion trajectories. Men’s involvement in abortion trajectories can be both direct and indirect. Contextual realities can make involving men in abortions a necessity, rather than a choice. The impact of male (lack of) involvement undermines the autonomy of a woman or girl to seek an abortion and shapes the conditions under which abortion-seekers are able to access care. This scoping review demonstrates the need for better understanding of the mechanisms, causes and intensions behind male involvement, centring the abortion seeker within this.

Résumé

La participation des hommes à l'interruption de grossesse est importante, et touche à des facteurs individuels, communautaires et généraux qui modèlent les parcours de soins relatifs à l'avortement. Cet examen de portée recense des données provenant de pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire en rapport avec la participation des hommes aux parcours d'avortement. Cinq bases de données ont fait l'objet de recherches, à l'aide de termes de recherche, pour obtenir 7493 articles publiés en anglais entre le 01.01.2010 et le 20.12.2019. Trente-sept articles réunissaient les critères relatifs à la participation masculine dans les parcours de l'avortement des femmes et ont été synthétisés à l'aide d'un cadre de recherche de soins relatifs à l'avortement. La majorité des études avaient été menées en Afrique subsaharienne et étaient qualitatives. Les données indiquaient que la participation masculine était importante, et qu'elle influençait la capacité d'une femme ou d'une jeune fille à révéler sa grossesse ou sa décision d'avorter. Les hommes en tant que partenaires étaient particulièrement influents, contrôlant les ressources nécessaires pour l'accès à l'avortement, et prodiguant ou retirant leur soutien à l'avortement. Le déni ou le rejet de la paternité était une étape critique dans le parcours de beaucoup de femmes pour avorter. La participation des hommes peut être à la fois directe et indirecte. Les réalités contextuelles peuvent faire de la participation masculine une nécessité plutôt qu'un choix. L'impact de la participation des hommes (ou de leur manque de participation) sape l'autonomie dont dispose une femme ou une jeune fille pour demander un avortement et façonne les conditions dans lesquelles les femmes souhaitant interrompre leur grossesse peuvent avoir accès aux soins. Cette étude de portée démontre la nécessité de mieux comprendre les mécanismes, les causes et les intentions derrière la participation des hommes, en se centrant sur la personne qui demande l'avortement.

Resumen

La participación de los hombres en la trayectoria de aborto es significativa; se entrecruza con factores individuales, comunitarios y macro que influyen en los trayectos relacionados con los servicios de aborto. Esta revisión de alcance mapea la evidencia de países de bajos y medianos ingresos relacionada con la participación de los hombres en las trayectorias de aborto. Se utilizaron términos de búsqueda para realizar una búsqueda en cinco bases de datos, que produjo 7493 ítems publicados en inglés entre 01.01.2010-20.12.2019; 37 ítems reunieron los criterios de inclusión para ítems relacionados con la participación de hombres en las trayectorias de aborto de las mujeres y fueron sintetizados utilizando un marco de búsqueda de servicios relacionados con el aborto. La mayoría de los estudios fueron realizados en África subsahariana y fueron cualitativos. La evidencia indicó que la participación de los hombres era significativa, ya que influía en la capacidad de la mujer o niña para divulgar su decisión sobre su embarazo o aborto. Los hombres como parejas eran particularmente influyentes, ya que controlaban los recursos necesarios para el acceso a los servicios de aborto y proporcionaban o negaban el apoyo para un aborto. La negación o el rechazo de la paternidad fue un momento crítico en la trayectoria de aborto de muchas mujeres. La participación de los hombres en la trayectoria de aborto puede ser directa e indirecta. Las realidades contextuales pueden tornar la participación de los hombres en el aborto una necesidad, y no una elección. El impacto de la participación (o falta de participación) de los hombres socava la autonomía de una mujer o niña para buscar un aborto e influye en las condiciones bajo las cuales las personas que buscan un aborto son capaces de acceder a los servicios de aborto. Esta revisión de alcance demuestra la necesidad de entender mejor los mecanismos, causas e intenciones detrás de la participación de los hombres, centrando a la persona que busca el aborto en este marco.

Introduction

Pathways to abortion-related care can be complex and iterative and are affected across individual, community, national and international contexts. Men have a significant impact on the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of others. In 1994, the International Conference on Population and Development recognised this by outlining the need for further engagement with men and boys in its Programme for Action.Citation1 It aimed to grapple with how men contribute to shaping the contextual conditions under which women and girls have to navigate their SRHR.Citation2 Following the Programme for Action, there was an increase in policy and programming aimed at engaging men, particularly as “partners” in SRHR.Citation3 These have been particularly focused in low- and middle-income country (LMIC) settings.Citation4–6

Autonomous and free access to safe abortions remains a major concern across the world, particularly where resources and capabilities to provide safe abortion services are limited.Citation7,Citation6 Of less and least safe abortions, 97% are estimated to occur in LMIC contexts,Citation7 and contribute to higher rates of complications than safer abortions.Citation6 The conditions under which these abortions occur are shaped by intersecting abortion-specific, individual, and sub-/national factors,Citation8 including structurally violent, gendered power systems,Citation9 that implicate men in a person’s abortion-related care trajectory.

Engaging men is a critical mechanism to challenge and reshape the normative environment that shapes abortion.Citation10–12 However, it risks increasing men’s power and control by inserting them as actors into abortion trajectories.Citation13–15 Studies among abortion-seekers have consistently referenced the role and influence of men at the structural level and the individual level.Citation16 Evidence from the multi-country International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES)Citation17 emphasised that men were “substantially” involved in abortion decisions if a pregnancy was disclosed,Citation17 while evidence from abortion-seekers illustrates that a large proportion of women and pregnant people cite that their (male) partner was a reason for their decision to seek care.Citation18 This includes the potential benefits of partner involvement within care decisions, such as emotional, material, and financial support.Citation8–19

Previous evidence syntheses highlight that abortion care is linked to broader economic, social, and political structures,Citation20–22 focused on abortion and post-abortion care,Citation23,Citation24 as well as specifically self-management.Citation25,Citation26 Altshuler et al.’sCitation27 systematic review on the roles of men in abortion-related care was primarily focused on “male partners”, with studies ranging across 1985–2012. Studies were excluded if abortions were done outside of legal frameworks, due to fetal indications, or where men’s involvement was considered coercive. They found that male partners were involved in four areas: presence at medical facilities, participation in pre-abortion counselling, presence in the procedure room or while a partner obtained a medical abortion, and participation in post-abortion care.

The review emphasises the role of men as significant. However, considering the increasing need to engage men beyond their role as partners,Citation16,Citation28 in order to fully grapple with the normative environments and conditions under which women and pregnant people obtain care,Citation1,Citation29,Citation30 a broader scoping review of men’s involvement in abortions is both relevant and necessary.

Methods

This scoping review aims to map the recent evidence of men’s involvement in abortion-related care trajectories. It understands involvement to be both direct – where men are present in the decision-making process – and indirect – where men exert influence and shape an abortion trajectory without being actively involved in the decision-making process. This includes understanding how men have been included in research samples, methods used, and geographic foci, in order to consider how future research can develop the evidence. A scoping review is the most appropriate method, as it produces an overview of evidence rather than clinical or policy guidelines, which require a systematic review.Citation31 The protocol for this study is available.Citation32

This review utilises the abortion trajectories framework, developed by Coast et al.,Citation8 in order to situate men’s involvement. The framework establishes three intersecting domains that shape the trajectory of abortion, from the decision to abort, the ability to access care, choice of method, and outcomes of care. The first – abortion-specific experiences – begins with pregnancy awareness and includes time-orientated factors that shape the experience of care. The second – individual context – considers the characteristics and relations (e.g. interpersonal network) that influence whether a woman obtains abortion-related care. The final domain – (inter)national and sub-national contexts – includes the norms and contextual conditions within which an individual and their abortion are situated.

A note on terminology

Findings in this study refer to men and women. This reflects the language that was used within the included studies. It is not used to exclude the reality that people of any gender can and do become pregnant and require abortion care.Citation33,Citation34

Inclusion and exclusion

Articles were included if they met all the inclusion criteria: published between 01.01.2010 and 20.12.2019, research on humans, English language, peer-reviewed, focused on abortion, include men as the sample or evidence on men, or evidence on male providers.

The shifting landscape of abortion-related care trajectories, impacted by new technologies, methods, and legal changes, made a short publication date range suitable.Citation35,Citation36 Moreover, the only systematic review of men and abortion included publications between 1985 and 2012.Citation27 This evidence mapping aims to build on the current evidence on men’s involvement, whilst ensuring the studies included are relevant to the current abortion landscape.

In preference of depth over breadth of evidence, non-article publications (e.g. published abstracts) were excluded. Studies were included irrespective of geo-political categorisation, labelling them as either a high-income country (HIC) or LMIC study post hoc, using World Bank classifications.Footnote*

Databases and search strategy

Five social science databases (EMBASE, PsychINFO, MEDLINE (Ovid), CAB Direct, CINAHL) were searched using a web of connecting terms, including MeSH terms for MEDLINE (Ovid) and EMBASE where applicable (). These search terms were designed to reflect the focus on male involvement in women’s and girls’ abortion trajectories. The dates, language and peer-review were constrained in all journal searches. For EMBASE, PsychINFO and MEDLINE (Ovid), constraints to ensure only studies involving humans were used.

Table 1. Outline of search terms for EMBASE, PsychINFO, MEDLINE (Ovid), CAB Direct, CINAHL.

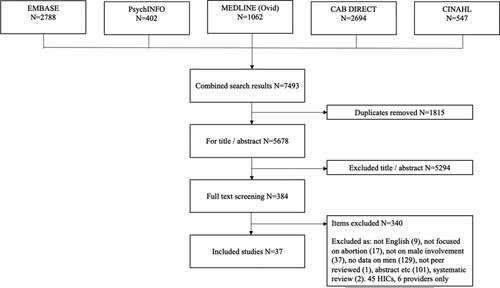

The author removed all duplicates before screening the titles and abstracts (TIAB) of articles, excluding any that did not indicate meeting the full set of inclusion criteria. A full-text screening of all included articles was then conducted. After a combined result of 7493 articles, 1815 were excluded as duplicates, 5678 were screened on TIAB (see ). A 5% sub sample of studies included for TIAB was cross checked by a research assistant, Clara Opoku Agyemang (see Methodological limitations).

Studies with a focus on abortion were included if they had men in the sample, or if reference was made to men’s involvement, regardless of whether the sample included men. The decision was made to be more inclusive for full-text screening, to reflect that the gender of parents, partners, friends, and family members might not be specified in the abstract. 384 articles were taken from TIAB to full-text screening. Of these, 9 were not in English, 17 not focused on abortion, 37 did not include male involvement, 129 had no evidence on men, 1 was not peer-reviewed, 101 were abstracts, posters, etc., and 2 were systematic reviews.

A total of 88 studies were included across geographies. The decision to separate the scoping review between LMICs (n = 43) and high-income countries (n = 45) reflects the nature of policy and research within these geo-political domains. LMICs are more directly impacted by global health discourse and rhetoric, illustrated by the increasing focus on men in global health policies within these contexts – for example in the recent maternal mortality reduction initiatives in LMICs.Citation37,Citation38 Thus, this evidence mapping can engage with specific audiences and political currents that shape the research agenda in LMICs.

Of the 43 studies taken to full-text screening, six of these related solely to abortion providers, which was an initial component of interest. However, the data extraction process indicated that the research on providers was less developed with regard to involvement. This scoping review, therefore, presents the results of men’s involvement exclusive of men who work within medicalised spaces. Thirty-seven studies have been included for this review.

Data extraction was conducted on Endnote X9.Citation39 This followed a codebook that had categories for background information (author, date, study setting, country(ies) of study), study information (methods, sample, recruitment sites), and primary outcomes of interest based on the abortion trajectories framework (abortion-specific experiences, individual context, (inter)national and sub-national contexts). These data were extracted solely by the author (JS). A copy of the extraction codebook is available on request from the author and the abridged summary table can be found in Appendix. A quality assessment of the included studies was not conducted, as this is not standard protocol for a scoping review.Citation31 The quality of the studies is not essential when mapping the existing evidence and gaps.

Methodological limitations

The inclusion criteria reflect the constraints of the research team, and therefore, only studies in English were included. This scoping review is, therefore, limited to English-language studies and does not reflect the full scope of evidence on men’s involvement in abortion published in other languages or on platforms outside of the databases used.

Due to resource constraints, the majority (95%) of studies in the evidence mapping were screened by the author, with a randomly selected 5% sub-sample blind double-screened by a research assistant (RA). “Blind” refers to neither reviewer knowing the results of the other’s screening until after both are completed. The purpose of this was to identify any systematic subjective biases in the screening process by the author, through emergent discrepancies in results. Within the 5% sub-sample, if minor (<1%) discrepancies were found, these would be discussed and an outcome for each agreed upon. Efforts were made prior to conducting the screening to ensure that both the researcher and RA felt comfortable with the review and the process of screening, so as to facilitate a discussion space for any discrepancies. If there were major (>1%) discrepancies, or systematic differences in which the same type of discrepancy over an exclusion/inclusion criterion emerged, then a larger sample of the studies would be drawn for a second blind review. No discrepancies did emerge during the sub-sample screening.

This sub-sample blind screening process does not negate the possible bias as a result of a single author screening but does aid in mitigating these biases. Moreover, it remains possible that papers were missed due to language constraints and during the screening. A previous systematic review on men and abortion similarly identified that the lack of detail in abstracts and gender disaggregation might have led to studies being erroneously excluded.Citation27 The decision to take more texts to full screening was aimed to mitigate that, as well as the need for a scoping review, as opposed to a systematic review, to allow for more flexibility in the methodological limitations.Citation31 Data extraction was conducted by one individual, due to constraints. It is possible that during data extraction, some data and evidence were missed, however, re-reviewing each full text for a second extraction review aimed to mitigate this possibility.

Results

The majority of studies (26/37) were qualitative, with the remainder quantitative (5/37) or mixed-method/unclear (6/37). Study contexts were predominantly located in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The largest sample size of the studies used Demographic and Health Survey data, which surveyed 3848 women in KyrgyzstanCitation40 and was the only nationally representative sample used. 23/37 studies used samples recruited in or referred from health facility lists (including pharmacies, abortion providers, post-abortion care facilities). The remainder were recruited through community networks/household surveys (10/37) or from schools or universities (4/37). See Appendix for included studies.

The results are divided into the three domains identified in the trajectories of abortion-related care framework: abortion-specific experiences, individual contexts, and (inter)national/sub-national contexts.Citation8 This allows for the scoping of men’s involvement to be mapped onto abortion trajectories.

Abortion-specific experiences

The majority of studies (27/37) reported on abortion-specific experiences, ranging from men’s direct and indirect involvement in decisions and responses to pregnancy disclosure, support for/against abortion, (non-)provision of material and physical resources, and access to abortion providers or methods.

Disclosure is a critical component of an abortion-related care trajectory, as it can impact whether and how a woman is able to obtain an abortion.Citation8 With the exception of a study of young men in the Philippines,Citation41 all evidence on the experience of disclosure was from women who had sought abortions, or studies where men were a secondary sample of interest. Women who had either sought abortion care or post-abortion care at a facility in Lusaka, Zambia, reported that the fear of disclosure also included fear of partner interference in the pregnancy or abortion decision, and fear of repercussions from fathers.Citation42

The fear of potential responses to disclosure also shaped the conditions under which women and girls made pregnancy and abortion decisions. A study with women aged 15–49 in Ghana highlighted how fears of being disowned, abused, or ejected by parents (not disaggregated between mothers and fathers) impacted their pregnancy disclosure and subsequent abortion decision-making.Citation43 Women in a study of abortion care-seekers in Ghana reported that fear of disclosure, including to partners, influenced their decision to self-manage,Citation44 and women in a second study interviewing men and women in Ghana reported similar fears of disclosure.Citation45 Among women in Brazil, fear of disclosing induced abortions related to their partner’s potential reaction, whereas disclosure of a miscarriage led to fear of family reactions.Citation46 In one study, men and boys also reported fears of disclosure of a pregnancy impacting their decisions and involvement in an abortion. Respondents in a qualitative study of attitudes towards abortion in the Philippines reported that their interference and pressuring for their partner to an obtain an abortion stemmed from their fears to disclose their partner’s pregnancy.Citation41

The most common evidence of men’s involvement in abortion-specific experiences was in the provision of material and physical resources. Financial provision was important in shaping the type of abortion that women obtained, as well as impacting women’s choice whether to disclose their pregnancies. In a study in Zambia, 50.4% of respondents reported that they had to involve men in their decisions in order to obtain the necessary finances to cover the costs of care.Citation47 A qualitative study of 112 women who had obtained abortions or post-abortion care in Zambia found that women’s disclosure was determined by their desires to maintain autonomy over their decision-making; for those that involved men in their pregnancy disclosure, this included men paying for the cost of care.Citation42 Adolescents in a study of reproductive decisions in Mexico City reported that their partner’s support for their abortions was conditional, and that the latter’s provision of resources impacted women’s and girls’ choice of abortion care.Citation48

The provision of resources was also interlinked with the provision of support for/against an abortion decision. In a qualitative study of 80 women in Nairobi, men were reported as exerting pressure on the decision-making process, including giving women money to influence them to obtain an abortion, as well as some men pushing for the pregnancy to continue.Citation49 A mixed-methods study with 401 women who had obtained abortions in Ghana reported that men utilised their position as “breadwinners” – providers and controllers of financial resources in the household – to pressure women to obtain abortions.Citation50

A study of men and women living in the same household in Uganda indicated that men considered their support of abortion to primarily involve the provision of finances for medicine, transportation, food, and costs of potential post-abortion care.Citation51 Evidence from men and women in Nigeria similarly found that men (as partners) provided financial, as well as emotional and material, support for women’s abortion-related care, though women also reported that men would give them money as a way of expressing their own desires for a woman to obtain an abortion.Citation52

Partners were not always the main sources of finances and resources, nor supportive, and adolescent men in a study in Peru reported that their financial dependence on parents reduced their role in pregnancy decision-making, which was also reported by adolescent women in the study.Citation53 An exploration of community perceptions of abortion in Kenya reported that women relied on boyfriends, as well as friends, relatives, and mothers, for financial support.Citation54 Moreover, in a qualitative study of 34 unmarried young women seeking abortions in India, only two reported that their partners provided financial support, with the majority citing mothers as supporting their abortion trajectories.Citation55

Non-financial support included emotional support, accompaniment, and supporting women’s autonomous decisions. Two studies of abortion experiences among 549 women in India reported that 92% of respondents were supported by their partners, of which 86% reported emotional support and 51% financial support.Citation56,Citation57 In Thailand, women who had experienced complications from abortions reported that finances were an important component of their partners’ support, alongside emotional support, particularly accompanying and telephoning them.Citation58 A study of women in Malaysia similarly found that men provided financial support, but also accompanied women and provided moral support, including googling whether abortions were considered a sin under the Islamic faith.Citation59

In a study with 1271 unmarried women aged 15–24 in China, 73–85% (variation due to multiple study sites) reported that their partner supported their abortion decisions, particularly by helping them seek care.Citation60 Another study of 29 women who had obtained an abortion in China found that men were able to accompany women and were involved in post-abortion family planning decisions.Citation61 An evaluation of an intervention to improve knowledge of medical abortion in Cambodia found that men learnt about abortions through newspapers and radio, with four of six men interviewed accompanying their partners for medical abortion and three accompanying for post-abortion care.Citation62

Among students in six public secondary schools in Nigeria, 26.8% of the 11% of men who knew a partner was pregnant provided assistance.Citation63 In a study with men in northern Ghana, the two main reasons given to support an abortion were for a person to finish schooling or for birth spacing; fewer men supported abortions for unplanned pregnancies.Citation64 Men in this study reported buying pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical abortion methods to support a partner’s abortion, in order to keep the abortion secret from the community.

Boyfriends were among the people that women in Ghana reported obtained abortion medication for them,Citation44 similarly found in a separate study among adolescents in Ghana.Citation65 In both studies, women reported being concerned over the safety and efficacy of the medicines. Evidence from women and adolescents who sought abortions or post-abortion care in Zambia included one adolescent reporting that her boyfriend’s brother gave her correct abortion information and provided support through his medical insurance scheme. In a study of medical abortion users and their partners in India, men reported accessing the medical abortion kits on behalf of their partners.Citation66 However, the study also reported that key health information on medical abortion was sometimes not passed on from the partner who obtained the kit to the person obtaining an abortion.

Support from men was reported as conditional on their own desired outcomes, and studies also reported that men could be coercive in attaining these. While young women in Mexico, aged 13–17, reported in focus groups that men offered emotional support for their pregnancy decisions, they discussed that these were often in accordance with men’s desired outcomes and not their own.Citation47 A study of women in Kenya included a respondent reporting that her husband found a provider to help him induce her abortion without her consent.Citation67 In the study, it was reported that almost all women expressed that they disagreed with their partner and feared possible consequences of their pregnancy disclosure (violence, divorce), which led them to seek care without telling their partner. However, some women disclosed their pregnancies in order to obtain financial support for care.

Individual context

Seventeen studies included evidence relating to the individual context within which a person seeks an abortion. These focused on the partner, family, and community context shaping the perceptions of pregnancy and abortion, denial/rejection of pregnancies.

Denial/rejection of pregnancies was one of the foremost ways that studies reported the context shaped a woman’s abortion trajectory. Rates of pregnancy denial could be high, with a study of 1047 secondary school students in Nigeria reporting that 48.2% of men whose partners were pregnant had denied paternity.Citation63 A study of women who had obtained abortions in Ghana reported that being unmarried and in a partnership was a factor in obtaining abortion care, as women reported that they feared their partner could and would abandon them, resulting in their navigation of the stigma of being an unmarried mother.Citation45 In a qualitative study of men and women at local universities in Nigeria, women reported that concerns over their partner denying a pregnancy and leaving them without a “responsible” partner influenced decisions to abort.Citation52

The impact of partner rejection of a pregnancy was emphasised in a study with women seeking abortions or post-abortion care in Zambia, who reported that their abortion was specifically due to partner rejection, which was also more likely among younger respondents than older.Citation42 Moreover, where women reported that their partner was present and knew of their abortion, the majority obtained safe abortions, while those whose partners were absent were predominantly seeking post-abortion care. A mixed-methods study of 15 pregnant adolescents aged 15–19 in Tanzania indicated that the decision to keep a pregnancy was done despite male partner rejection and led to feelings of regret towards becoming pregnant.Citation68 Of the 34 adolescents interviewed who had induced abortions in Lusaka, Zambia, 16 reported that their partners rejected or denied paternity and requested them to obtain an abortion.Citation69 This rejection of pregnancy included withholding financial support for the pregnancy or future childcare.

The broader individual context also included the attitudes and desires of partners, as well as the living conditions and the relationships of women and girls to their partners and families. Women and girls in Nairobi, Kenya, reported that their partner’s fertility desires meant that some respondents felt pressured into obtaining an abortion.Citation49 An analysis of the Kyrgyzstan Demographic and Health Survey, which had a sample of 3848 women aged 15–49, suggests that men’s attitude towards abortion was significantly associated with the likelihood of a woman obtaining an induced abortion.Citation40 However, among 142 university students in Ghana, women reported that their own beliefs, including religious beliefs, were important in their abortion decision-making, and that their partner’s and peers’ views were less influential.Citation70

A study with 401 women who had obtained abortions in Ghana found that knowledge of the law, occupational status, number of children living, and level of formal education all increased the odds that a women sought consent of male partners in comparison with those that sought consent from “others”, including friends, siblings, and aunts.Citation50 Living with parents, particularly fathers, was associated with increased pressure to allow their involvement in abortion decisions among adolescents who had been pregnant at least once in a study in Accra.Citation71

Many of the studies that reported on the family context, however, did not disaggregate between type of parent or carer. While studies in Peru,Citation53 Ghana,Citation43 and ZambiaCitation72 indicated that the relationship an adolescent or young person had with their parents and family influenced their abortion trajectory, it was not clear if male family members had differing involvement to female family members. In Peru, some male respondents argued that the decisions on pregnancy and abortion were theirs, whilst others supported women’s decisions.Citation53 Women and girls described that being younger or less informed was linked to partners taking control of decisions, in addition to describing being coerced to have an abortion by partners and parents.

Evidence also suggests that the type of relationship between partners influenced abortion trajectories, particularly women’s perceptions of their partner as stable and (maritally) committed. In two studies – one in Mexico and one in Sri Lanka – the stability and perceived future of a relationship impacted the abortion trajectory. For women in Mexico, all women whose partners were not involved obtained an abortion.Citation48 Among Sri Lankan women, partners who refused to marry or denied paternity also had an impact on the decision to obtain an abortion.Citation73 In addition, respondents cited the involvement of their brothers in pressuring them to obtain an abortion, if they were pregnant while unmarried. A study of pregnancy reactions among adolescents who recently had an abortion in Ghana suggested that a partner being a student or unemployed could lead to them suggesting an abortion, and respondents also cited men’s ability to deny a pregnancy as significant.Citation65

(Inter)national and sub-national contexts

Seven studies reported on how the (inter)national and sub-national contexts are both shaped and maintained by men, as well as having an influence on men’s involvement in abortion decisions. These studies primarily focused on the role of men in operationalising social norms around abortion in their response to a pregnancy or abortion. Community leaders in a study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, who were all male, reported that women who sought abortions would be actively stigmatised, isolated, and/or forced to leave their communities.Citation74 However, in instances where a women’s partner was abusive, alcoholic, or unemployed, or where there were financial difficulties, community leaders were more supportive of abortions, as well as considering themselves responsible for post-abortion care. Men could utilise cultural norms to involve themselves in abortion decision-making. A study of the national discourses around masculinities and abortion in South Africa revealed that the “New Man” discourse – referring to men who considered themselves committed, caring, and loving to their partners and family – was a mechanism through which men reported being supportive of pregnancies to order to dissuade partners from obtaining an abortion.Citation75

Attitudes towards abortions that drew on, and bolstered, prevailing social and cultural norms were complex and varied. In a study of abortion in Uganda, men responded that they were generally not supportive of women having an abortion, aligning their beliefs with prevailing socio-cultural norms, which shaped their decisions to provide support or finances in the event of a pregnancy.Citation51 Young Filipino men discussed in focus groups how they viewed abortion as a “sin” and that, in accordance with their normative environment, they were not supportive of women obtaining care.Citation41 However, in-depth interviews indicated that these men considered abortions acceptable under certain conditions. Among men in Ghana, abortion was similarly labelled as a “sin” and unacceptable by community norms, although these norms were also operationalised by men in focus groups to discuss how stigmatised pregnancies were a reason to encourage an abortion.Citation64

While men in a study in Kenya were reported to consider women who had abortions as not “wife material”, a norm which forced some women to relocate in order to obtain care, men and women in the study also reported that abortions were increasingly normalised in the community.Citation54 Community norms could also be enacted to minimise men’s involvement. In a study of parental attitudes towards induced abortion in Nigeria, mothers reported that it was a social necessity that decisions be between mother and daughter, while fathers suggested that their role was as breadwinners.Citation76

Discussion and conclusion

Studies highlight the potentially significant – and diverse – role that men and boys can have in women and pregnant people’s abortion trajectories across low- and middle-income settings. The evidence emphasises that men’s involvement was present across abortion-specific experiences, the individual context of an abortion seeker, and the community context. This review complements broader evidence on the role of men in sexual and reproductive health, which has highlighted their ability to influence fertility and contraceptive decisions,Citation77–82 and shape care-seeking through financial gatekeeping,Citation83 in addition to providing positive support for partners.Citation14 Similarly to this broader evidence on men and SRHR,Citation84–86 this review highlights the diverse implications of men’s involvement in abortion trajectories.

Partners – boyfriends, husbands, sexual partners, etc. – are the men who are most often included in study samples or referred to by women and pregnant people, mirroring the focus on partners in global health discourse.Citation87 However, included studies also indicated that other male relations – including fathers and brothers – can be important, as well as how men – such as community leaders – are able to shape the normative structures that can govern abortion trajectories. While parents were referenced in numerous studies, this was not always disaggregated to investigate whether there were differences between parental roles of fathers and mothers, as well as other guardians or carers.

In these studies, evidence on men’s involvement in abortion trajectories was particularly prevalent for abortion-specific experiences and highlighted how this intersected across experiences of disclosure and financial and emotional support. The real or perceived expectations of how a partner, or sometimes father, would react to a pregnancy had an impact on a woman’s decision over pregnancy or abortion disclosure. The most frequently reported area of men’s involvement in abortion-specific experiences in studies, however, came in the control and provision of resources. This was referred to in studies across different contexts, emphasising the widespread nature of men’s control of resources and finances. Women are, therefore, made to navigate the complexities of disclosing their abortion intention to possible negative reactions, or having the resources and finances necessary for transport or facility costs limited. The included studies suggest that men are integral to creating the conditions that shape the ability of women and pregnant people to make free and autonomous choices on their abortion intention and desired care pathway.

Studies also provide evidence of how men shape both the individual contexts and the broader environments within which women and pregnant people seek care. The relationship between a woman or pregnant person and their partner, as well as the age of an adolescent, impacted their decision-making and the trajectory of their abortion. Studies with a sample of men most frequently provided evidence of men’s roles in shaping the broader discourse of abortion, upholding and (re)producing contextual norms. These norms create the conditions under which pregnancies can be stigmatised, resulting in women or pregnant people seeking abortions, or that require abortions to be conducted privately away from institutions or public facilities. These norms and contexts were linked to the denial or rejection of paternity, which in turn (re)shapes the contextual conditions that impact an abortion trajectory.

It is not possible to ascertain the extent to which this indirect involvement from men, particularly their involvement in shaping the broader conditions of care, shapes the explicit choices and experiences of women and pregnant people seeking abortions. Few studies can make clear in the evidence whether men’s involvement was sought by women or pregnant people as part of their free and autonomous choice for care, or out of necessity for information, resources, and to make the context of their abortion more acceptable. Moreover, biases of the sampling frames are not (always) clear in the current studies. For example, men who are sampled often accompanied their partners and might be more supportive by virtue of this, and abortion experiences outside of facilities where participant recruitment occurs are less represented.

In addition to the methodological considerations, this scoping review is limited in its capacity to synthesise evidence to make policy- and clinically based recommendations, in comparison to a systematic review. However, the strength of this review is the map of evidence for where men are currently involved in abortion trajectories. It provides a roadmap for future research, and exploration of other areas within the abortion-related care trajectories framework where men are both directly and indirectly involved. Evidence on men emerges from women’s own narratives, with fewer studies including men in their sample, and fewest having men as their primary sample.

The influence that men and boys can exert can directly and indirectly undermine the autonomy of women, girls, and pregnant people, representing a major barrier to universal sexual and reproductive health and rights. The ability of women, girls, and pregnant people to navigate the contextual realities of abortion-related care is too often defined by men, which limits the fundamental right to autonomy and safe, legal, and free choice for people seeking abortions. Future research could consider interrogating the mechanisms, causes, and intentions that drive men’s attitudes and behaviours, to better understand the conditions under which women and pregnant people seek abortions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council under grant number ES/P000622/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Basu AM. ICPD: what about men’s rights and women’s responsibilities? Health Transit Rev. 1996;6(2):225–227. www.jstor.org/stable/40652220.

- Saewyc EM. What about the boys? The importance of including boys and young men in sexual and reproductive health research. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(1):1–2. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.002.

- Chandra-Mouli V, Ferguson BJ, Plesons M, et al. The political, research, programmatic, and social responses to adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights in the 25 years since the International Conference on Population and Development. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(6, Supplement):S16–S40. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.011.

- Dodoo FN, Frost AE. Gender in African population research: the fertility/reproductive health example. Ann Rev Soc. 2008;34; doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134552.

- Dodoo FN-A. Men matter: additive and interactive gendered preferences and reproductive behavior in Kenya. Demography. 1998;35(2):229–242. doi:10.2307/3004054.

- Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress – sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2642–2692. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9.

- Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. The Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–2381. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4.

- Coast E, Norris AH, Moore AM, et al. 2018/03/01/). Trajectories of women’s abortion-related care: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2018;200:199–210. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.035.

- Nandagiri R, Coast E, Strong J. COVID-19 and abortion: making structural violence visible. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46(Supplement 1):83–89. doi:10.1363/46e1320.

- Davis J, Vyankandondera J, Luchters S, et al. Male involvement in reproductive, maternal and child health: a qualitative study of policymaker and practitioner perspectives in the Pacific. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):81–81. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0184-2.

- Hartmann M, Khosla R, Krishnan S, et al. How are gender equality and human rights interventions included in sexual and reproductive health programmes and policies: a systematic review of existing research foci and gaps. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0167542–e0167542. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167542.

- Ramirez-Ferrero E. The role of men as partners in the prevention of mothers-to-child transmission of HIV and in the promotion of sexual and reproductive health. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20:103–109. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39642-0.

- Adewole I, Gavira A. Sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: an urgent need to change the narrative. The Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2585–2587. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30888-2.

- Sternberg P, Hubley J. Evaluating men’s involvement as a strategy in sexual and reproductive health promotion. Health Promot Int. 2004, Sep;19(3):389–396. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah312.

- Tokhi M, Comrie-Thomson L, Davis J, et al. Involving men to improve maternal and newborn health: a systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191620–e0191620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191620.

- Hook C, Miller A, Shand T, et al. Getting to equal: engaging men and boys in sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and gender equality. Washington (DC): Promundo-US; 2018.

- Barker G, Contreras JM, Heilman B, et al. Evolving men: initial: results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES). Washington (DC): International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Promundo; 2011.

- Chibber KS, Biggs MA, Roberts S, et al. The role of intimate partners in women’s reasons for seeking abortion. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:e131–e138, doi:10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.007.

- Altshuler AL, Ojanen-Goldsmith A, Blumenthal PD, et al. (2021/09/01/). “Going through it together”: being accompanied by loved ones during birth and abortion. Soc Sci Med. 2021;284:114234, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114234.

- Coast E, Lattof SR, Meulen Rodgers Y, et al. The microeconomics of abortion: a scoping review and analysis of the economic consequences for abortion care-seekers. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0252005, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252005.

- Moore B, Poss C, Coast E, et al. The economics of abortion and its links with stigma: a secondary analysis from a scoping review on the economics of abortion. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246238, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246238.

- Shearer JC, Walker DG, Vlassoff M. Costs of post-abortion care in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;108(2):165–169. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.037.

- Rogers C, Dantas JAR. Access to contraception and sexual and reproductive health information post-abortion: a systematic review of literature from low- and middle-income countries. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2017, Oct;43(4):309–318. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101469.

- Tripney J, Kwan I, Bird KS. Postabortion family planning counseling and services for women in low-income countries: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87(1):17–25. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.014.

- Endler M, Lavelanet A, Cleeve A, et al. Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;126(9):1094–1102. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15684.

- Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, et al. Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020, Feb;63:87–110. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.08.002.

- Altshuler AL, Nguyen BT, Riley HE, et al. Male partners’ involvement in abortion care: a mixed-methods systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48:209–219. doi:10.1363/psrh.12000.

- Shand T, Marcell AV. Engaging men in sexual and reproductive health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021.

- Dudgeon MR, Inhorn MC. Gender, masculinity, and reproduction anthropological perspectives. In: MC Inhorn, T Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, H Goldberg, M la Cour Mosegaard, editors. Reconceiving the second sex. New York: Berghahn Books; 2009a. 1 ed., p. 72–102. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qd6sr.7.

- Dudgeon MR, Inhorn MC. Men’s influences on women’s reproductive health medical anthropological perspectives. In: MC Inhorn, T Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, H Goldberg, M la Cour Mosegaard, editors. Reconceiving the second sex. New York: Berghahn Books; 2009b. 1 ed., p. 103–136. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qd6sr.8.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: E Aromataris, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis, JBI; 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Strong J. Men’s involvement in women’s abortion related care: a protocol for a scoping study. Figshare. 2021, doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.14784915.v1.

- Riggs DW, Pearce R, Pfeffer CA, et al. Men, trans/masculine, and non-binary people’s experiences of pregnancy loss: an international qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):482, doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03166-6.

- Riggs DW, Pfeffer CA, Pearce R, et al. Men, trans/masculine, and non-binary people negotiating conception: normative resistance and inventive pragmatism. Int J Transgender Health. 2021;22(1-2):6–17. doi:10.1080/15532739.2020.1808554.

- Berer M. Abortion Law and Policy around the world in search of decriminalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):13–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/90007912.

- Broussard K. The changing landscape of abortion care: embodied experiences of structural stigma in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Soc Sci Med. 2020;245:112686, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112686.

- McLean KE. Men’s experiences of pregnancy and childbirth in Sierra Leone: reexamining definitions of “male partner involvement”. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113479, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113479.

- World Health Organization. (2015). WHO Recommendations on Health Promotion Interventions for Maternal and Newborn Health.

- Analytics C. (2018). The Little EndNote How-To Book: EndNote Training. Available from: https://clarivate.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=42104347.

- Shekhar C, Sekher TV, Sulaimanova A. Role of induced abortion in attaining reproductive goals in Kyrgyzstan: a study based on KRDHS-1997. J Biosoc Sci. 2010;42(4):477–492. doi:10.1017/s002193201000009x.

- Hirz AE, Avila JL, Gipson JD. The role of men in induced abortion decision making in an urban area of the Philippines. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138(3):267–271. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12211.

- Freeman E, Coast E, Murray SF. Men’s roles in women’s abortion trajectories in urban Zambia. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;43(2):89–98. doi:10.1363/43e4017.

- Challa S, Manu A, Morhe E, et al. Multiple levels of social influence on adolescent sexual and reproductive health decision-making and behaviors in Ghana. Women Health. 2018;58:434–450. doi:10.1080/03630242.2017.1306607.

- Rominski SD, Lori JR, Morhe ES. “My friend who bought it for me, she has had an abortion before.” The influence of Ghanaian women’s social networks in determining the pathway to induced abortion. J Fam Plan Reprod Health Care. 2017;43:216–221. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101502.

- Schwandt HM, Creanga AA, Adanu RM, et al. Pathways to unsafe abortion in Ghana: the role of male partners, women and health care providers. Contraception. 2013;88:509–517. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.03.010.

- Nonnenmacher D, Benute GR, Nomura RM, et al. Abortion: a review of women’s perception in relation to their partner’s reactions in two Brazilians cities. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992). 2014;60:327–334. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed15&NEWS=N&AN=603638199; Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ramb/v60n4/0104-4230-ramb-60-04-0327.pdf.

- Leone T, Coast E, Parmar D, et al. The individual level cost of pregnancy termination in Zambia: a comparison of safe and unsafe abortion. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(7):825–833. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv138.

- Tatum C, Rueda M, Bain J, et al. Decision making regarding unwanted pregnancy among adolescents in Mexico City: a qualitative study. Stud Fam Plann. 2012;43(1):43–56. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00301.x.

- Izugbara C, Egesa C. The management of unwanted pregnancy among women in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Sex Health. 2014;26(2):100–112. doi:10.1080/19317611.2013.831965.

- Kumi-Kyereme A, Gbagbo FY, Amo-Adjei J. Role-players in abortion decision-making in the Accra metropolis, Ghana. Reprod Health. 2014, Sep 16;11:70, doi:10.1186/1742-4755-11-70.

- Moore AM, Jagwe-Wadda G, Bankole A. Men’s attitudes about abortion in Uganda. J Biosocial Science. 2011;43; doi:10.1017/s0021932010000507.

- Omideyi AK, Akinyemi AI, Aina OI, et al. Contraceptive practice, unwanted pregnancies and induced abortion in Southwest Nigeria. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 1):S52–S72. doi:10.1080/17441692.2011.594073.

- Palomino N, Padilla MR, Talledo BD, et al. The social constructions of unwanted pregnancy and abortion in Lima, Peru. Glob Public Health. 2011;6:73–89. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed12&NEWS=N&AN=364573323.

- Ushie BA, Juma K, Kimemia G, et al. Community perception of abortion, women who abort and abortifacients in Kisumu and Nairobi counties, Kenya. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226120, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226120.

- Sowmini CV. Delay in termination of pregnancy among unmarried adolescents and young women attending a tertiary hospital abortion clinic in Trivandrum, Kerala, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21(41):243–250. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/43288980.

- Kalyanwala S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Zavier AJ, et al. Experiences of unmarried young abortion-seekers in Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(3):241–255. doi:10.1080/13691058.2011.619280.

- Kalyanwala S, Zavier AJ, Jejeebhoy S, et al. Abortion experiences of unmarried young women in India: evidence from a facility-based study in Bihar and Jharkhand. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010, Jun;36(2):62–71. doi:10.1363/ipsrh.36.062.10.

- Chatchawet W, Sripichyakan K, Kantaruksa K, et al. Support from Thai male partners when an unwanted pregnancy is terminated. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res Thail. 2010;14:249–261. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=104954379&site=ehost-live.

- Tong WT, Low WY, Wong YL, et al. A qualitative exploration of contraceptive practice and decision making of Malaysian women who had induced abortion: a case study. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2014, Sep;26(5):536–545. doi:10.1177/1010539513514434.

- Zuo X, Yu C, Lou C, et al. Factors affecting delay in obtaining an abortion among unmarried young women in three cities in China. Asia-Pacific Population J. 2012;30(1):35–50. doi:10.18356/758e5c7a-en.

- Che Y, Dusabe-Richards E, Wu S, et al. A qualitative exploration of perceptions and experiences of contraceptive use, abortion and post-abortion family planning services (PAFP) in three provinces in China. BMC Women’s Health. 2017;17:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0458-z.

- Petitet PH, Ith L, Cockroft M, et al. Towards safe abortion access: an exploratory study of medical abortion in Cambodia. Reprod Health Matters. 2015, Feb;22(44 Suppl 1):47–55. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(14)43826-6.

- Alex-Hart BA, Okagua J, Opara PI. Sexual behaviours of secondary school students in Port Harcourt. J Adv Medicine Medical Res. 2014;6(3):325–334.

- Marlow HM, Awal AM, Antobam S, et al. Men’s support for abortion in Upper East and Upper West Ghana. Cult Health Sex. 2019;21:1–10. doi:10.1080/13691058.2018.1545921.

- Aziato L, Hindin MJ, Maya ET, et al. Adolescents’ responses to an unintended pregnancy in Ghana: a qualitative study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:653–658. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.06.005.

- Srivastava A, Saxena M, Percher J, et al. Pathways to seeking medication abortion care: a qualitative research in Uttar Pradesh, India. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0216738, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216738.

- Rehnstrom Loi U, Lindgren M, Faxelid E, et al. Decision-making preceding induced abortion: a qualitative study of women’s experiences in Kisumu, Kenya. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):166, doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0612-6.

- Mwilike B, Shimoda K, Oka M, et al. A feasibility study of an educational program on obstetric danger signs among pregnant adolescents in Tanzania: a mixed-methods study. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2018;8:33–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijans.2018.02.004.

- Dahlbäck E, Maimbolwa M, Yamba CB, et al. (2010/04/01). Pregnancy loss: spontaneous and induced abortions among young women in Lusaka, Zambia. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(3):247–262. doi:10.1080/13691050903353383.

- Appiah-Agyekum NN, Sorkpor C, Ofori-Mensah S. Determinants of abortion decisions among Ghanaian university students. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27:79–84. doi:10.1515/ijamh-2014-0011.

- Bain LE, Zweekhorst MBM, Amoakoh-Coleman M, et al. To keep or not to keep? Decision making in adolescent pregnancies in Jamestown, Ghana. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0221789–e0221789. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221789.

- Coast E, Murray SF. “These things are dangerous”: understanding induced abortion trajectories in urban Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:201–209. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.025.

- Olsson P, Wijewardena K. Unmarried women’s decisions on pregnancy termination: qualitative interviews in Colombo. Sri Lanka. Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. 2010;1:135–141. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2010.07.005.

- Steven VJ, Deitch J, Dumas EF, et al. “Provide care for everyone please”: engaging community leaders as sexual and reproductive health advocates in North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):98–98. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0764-z.

- Macleod CI, Hansjee J. Men and talk about legal abortion in South Africa: equality, support and rights discourses undermining reproductive ‘choice’. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15:997–1010. doi:10.1080/13691058.2013.802815.

- Obiyan MO, Agunbiade OM. Paradox of parental involvement in sexual health and induced abortions among in-school female adolescents in Southwest Nigeria [Psychosocial & Personality Development 2840]. Sexuality & Culture: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly. 2014;18:847–869. doi:10.1007/s12119-014-9229-2.

- DeRose L, Ezeh A. Decision-making patterns and contraceptive use: evidence from Uganda. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2010;29:423–439. doi:10.1007/s11113-009-9151-8.

- DeRose LF, Dodoo FN-A, Patil V. Fertility desires and perceptions of power in reproductive conflict in Ghana. Gender Soc. 2002;16(1):53–73. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/3081876.

- DeRose LF, Ezeh AC. Men’s influence on the onset and progress of fertility decline in Ghana, 1988-98. Popul Stud. 2005;59(2):197–210. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30040456.

- John NA, Babalola S, Chipeta E. Sexual pleasure, partner dynamics and contraceptive use in Malawi. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015, Jun;41(2):99–107. doi:10.1363/4109915.

- Kriel Y, Milford C, Cordero J, et al. Male partner influence on family planning and contraceptive use: perspectives from community members and healthcare providers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):89–89. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0749-y.

- Shattuck D, Kerner B, Gilles K, et al. Encouraging contraceptive uptake by motivating men to communicate about family planning: the Malawi Male Motivator project. Am J Public Health. 2011, Jun;101(6):1089–1095. doi:10.2105/ajph.2010.300091.

- Story WT, Barrington C, Fordham C, et al. Male involvement and accommodation during obstetric emergencies in rural Ghana: a qualitative analysis. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;42(4):211–219. doi:10.1363/42e2616.

- Chikovore J, Lindmark G, Nystrom L, et al. The hide-and-seek game: men’s perspectives on abortion and contraceptive use within marriage in a rural community in Zimbabwe. J Biosoc Sci. 2002, Jul;34(3):317–332. doi:10.1017/s0021932002003176.

- Kalmuss D, Tatum C. Patterns of men’s use of sexual and reproductive health services. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007, Jun;39(2):74–81. doi:10.1363/3907407.

- Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(6):604, doi:10.1136/jech-2014-204784.

- Wentzell EA, Inhorn MC. Reconceiving masculinity and ‘men as partners’ for ICPD beyond 2014: insights from a Mexican HPV study. Global Public Health: ICPD Both Before and Beyond 2014: The Challenges of Population and Development in the Twenty-First Century. 2014;9(6):691–705. doi:10.1080/17441692.2014.917690.