Abstract

Internally displaced women are underserved by health schemes and policies, even as they may face greater risk of violence and unplanned pregnancies, among other burdens. There are an estimated 450,000 internally displaced persons in India, but they are not formally recognised as a group. Displacement has been a common feature in India’s northeast region. This paper examines reproductive and maternal health (RMH) care-seeking among Bru displaced women in India. The study employed qualitative methodology: four focus group discussions (FGDs) were held with 49 displaced Bru women aged 18–45 between June and July 2018; three follow-up interviews with FGD participants and five in-depth interviews with community health workers (Accredited Social Health Activists – ASHAs) in camps for Bru displaced people in the Indian state of Tripura. All interviewees gave written or verbal informed consent; discussions were conducted in the local dialect, recorded, and transcribed. Data were indexed deductively from a dataset coded using grounded approaches. Most women were unaware of many of the RMH services provided by health facilities; very few accessed such care. ASHAs had helped increase institutional deliveries over the years. Women were aware of temporary contraceptive methods as well as medical abortion, but lacked awareness of the full range of contraceptive options. Challenges in accessing RMH services included distance of facilities from camps, and multiple costs (for transport, medicines, and informal payments to facility staff). The study highlighted a need for comprehensive intervention to improve RMH knowledge, attitudes, and practices among displaced women and to reduce access barriers.

Résumé

Les femmes déplacées à l’intérieur de leur pays sont sous-desservies par les plans et politiques de santé, même si elles peuvent être plus à risque de violences et de grossesses non désirées, parmi d’autres contraintes. On estime que l’Inde abrite près de 450 000 déplacés internes, mais ils ne sont pas reconnus en tant que groupe. Le déplacement est une caractéristique commune dans le Nord-Est de l’Inde. Cet article examine la demande de soins de santé maternelle et reproductive (SMR) parmi les femmes bru déplacées en Inde. L’étude a employé une méthodologie qualitative: quatre discussions par groupe d’intérêt avec des femmes déplacées âgées de 18 à 45 ans issues de la communauté bru, trois entretiens de suivi avec des participantes aux discussions de groupe et cinq entretiens approfondis avec des agents de santé communautaires connus sous le nom d’activistes agréés de santé sociale (ASHA) dans des camps pour les Brus déplacés dans l’État indien de Tripura. Toutes les personnes ayant participé à des entretiens ont donné leur consentement écrit; les discussions ont été menées en dialecte local, enregistrées et transcrites. Les données pour cette analyse ont été indexées de manière déductive à partir d’un ensemble de données codées utilisant des méthodes ancrées. La plupart des femmes ne connaissaient pas nombre des services de SMR assurés par les centres de santé; très peu d’entre elles avaient accès à ces soins. Au fil des années, les agents ASHA avaient aidé à augmenter le nombre d’accouchements en milieu hospitalier. Les femmes connaissaient les méthodes contraceptives temporaires comme l’avortement médicamenteux, mais n’étaient pas informées de tout l’éventail des options contraceptives. Parmi les difficultés pour avoir accès aux services de SMR, il convient de citer l’éloignement des centres depuis les camps, et les multiples coûts (pour le transport, les médicaments et les paiements informels au personnel des centres). L’étude a mis en lumière la nécessité d’une intervention globale pour améliorer les connaissances, les attitudes et les pratiques en matière de SMR parmi les femmes déplacées et pour lever les obstacles à l’accès.

Resumen

Las mujeres desplazadas internamente son desatendidas por esquemas y políticas de salud, aun cuando podrían correr mayor riesgo de violencia y embarazos no planificados, entre otras cargas. Según las estimaciones, en India hay 450,000 personas desplazadas internamente, pero no son reconocidas oficialmente como grupo. El desplazamiento ha sido una característica común de la región noreste de India. Este artículo examina la búsqueda de servicios de salud reproductiva y materna (SRM) entre mujeres desplazadas en Bru, India. El estudio empleó metodología cualitativa: cuatro discusiones en grupos focales (DGF) con mujeres desplazadas de 18 a 45 años provenientes de la comunidad de Bru, tres entrevistas de seguimiento con participantes de DGF y cinco entrevistas a profundidad con agentes de salud comunitaria conocidas como Activistas Acreditadas en Salud Social (ASHA, por sus siglas en inglés) en campos de personas desplazadas de Bru, en el estado indio de Tripura. Todas las personas entrevistadas dieron su consentimiento informado escrito; las discusiones fueron realizadas en el dialecto local, grabadas y transcritas. Los datos de este análisis fueron indexados de manera deductiva de un conjunto de datos codificado utilizando enfoques fundamentados. La mayoría de las mujeres no eran conscientes de muchos de los servicios de SRM proporcionados por los establecimientos de salud; muy pocas accedían a esos servicios. Las ASHA habían ayudado a aumentar los partos institucionales a lo largo de los años. Las mujeres eran conscientes de métodos anticonceptivos provisionales y del aborto con medicamentos, pero carecían de conocimientos sobre toda la gama de opciones anticonceptivas. Entre los retos para acceder a los servicios de SRM figuraban la distancia entre los establecimientos de salud y los campos, y múltiples gastos (por transporte, medicamentos y pagos informales al personal de salud). El estudio destacó la necesidad de una intervención integral para mejorar los conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas de SRM entre mujeres desplazadas y para disminuir las barreras al acceso.

Background

In recent years, conflict-driven internal displacement has been recognised increasingly as a global health issue with devastating impacts on the mental and physical health of displaced people.Citation1,Citation2 The South Asia region, which includes the five countries of India, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, and Pakistan, has a large population affected by protracted conflicts within and between countries.Citation3 In 2019, for example, conflict and violence led to 498,000 new displacements in the region as a whole and by the end of the year four million people were living in displacement due to conflict.Citation4

Internally Displaced People (IDPs) are those who have remained within the borders of their own countries, whereas refugees have crossed an international border.Citation5 Both IDPs and refugees face loss of home and livelihood, as well as poor access to education and health care; these factors are associated with human rights violations.Citation6 However, there are differences. While refugee and international migrants are protected by international agreements and frameworks which provide them with special protection and entitlements, IDPs do not have the same protections.Citation7,Citation8 Thus the situation of IDPs is more acute, compared to refugees or migrants, in the absence of protection from international policies and organisations, and they depend on the national authorities of their home countries to protect their rights and to see to their welfare.Citation7 Recently, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees provided Guiding Principles to deal with internal displacement but the guidelines do not provide the same kind of institutional arrangements as for refugees.Citation9,Citation10 Unfortunately, national legislation in many countries does not address the particularities of internal displacement and therefore countries do not have concrete policies on IDPs, leaving them with little recourse other than to struggle themselves for their basic rights.Citation7 A comprehensive understanding of IDPs and their health issues has remained a grey area in the field of public health.

It is known that women accounted for half of the estimated 50.8 million people displaced globally in 2019.Citation11 Like all IDPs, displaced women face human rights violations but they are often at greater risk than men.Citation6,Citation12 Displaced women are susceptible to unplanned pregnancies, unsafe abortions, violence, and sexually transmitted infectionsCitation8 and often have to take on the burden of family responsibilities at the expense of addressing their trauma and health needs.Citation13 This takes a large toll on women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights,Citation14 compounded by limited access to reproductive health care services.

India has localised areas of conflict, mostly confined to a few states or specific districts within particular states, where a combination of armed conflict, separatist insurgencies, and violence have erupted, often linked to politics, ethnicity, religion, and caste.Citation15 These are low-intensity conflicts, with sporadic outbursts continuing over a long period of time. It is estimated that in 2018, nearly 479,000 people were internally displaced as a result of conflict,Citation15 although this number may be an underestimate, given the neglect of internal displacement in policy overall.Citation7 Thus, rare if any efforts have yet been put in place to formulate policies or programmes to identify or guarantee health rights to IDPs such as those from the Bru (also known as Reang) indigenous community who have been living in protracted displacement for more than two decades. Moreover, there is limited understanding of the sexual and reproductive health of female IDPs in India.

Bru displaced people belonging to Mizoram state in the North-Eastern region of India were displaced following ethnic conflicts with the dominant Mizo indigenous community in 1997 and 2009.Citation16 It is estimated that approximately 34,000 indigenous Bru moved due to conflict to the neighbouring state of Tripura, where they have since been living in isolation in six makeshift camps.Citation16 The Tripura state government, with the support of the national government, offers a monthly survival stipend of roughly US$2 per adult and US$1 per child, with a ration quota of 600 gm of rice and lentils per day per adult, while children get half that amount.Citation16 As the status of these IDPs remains uncertain, even these concessions have been discontinued from time to time. For instance, in 2018, relief materials were discontinued as the displaced people opposed the national government’s decision to repatriate them to their home state at short notice, but were resumed following protests.Citation17,Citation18 Non-government organisation and media reports suggest that Bru displaced people are living in poverty and abysmal conditions with poor access to clean water, health, and education, with little prospect of improvement.Citation16,Citation19 Furthermore, not all the government schemes are expanded to Bru displaced people. For example, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA),Citation20 which provides supplementary wage employment to rural households, is not implemented in the camps. Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY)Citation21 – a national publicly funded health insurance scheme that covers inpatient and some outpatient care – is implemented in the camps, but its outreach is poor. While there is some knowledge about their living conditions, there are no data about the effect of protracted displacement on displaced Bru women’s health and access to reproductive and maternal healthcare.

Considering India’s commitment to Sustainable Development Goal 3,Citation22 it is pertinent to understand the situation of displaced women in order to fulfil the commitment to leaving no one behind. The country has had a dedicated national programme, known as the Reproductive and Child Health Programme, since 1997,Citation23 and in 2013, this was expanded and reformulated as the Reproductive Maternal Newborn Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) strategy, with a focus on disadvantaged women.Citation24 Several initiatives introduced under RMNCH+A, such as the Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK), which provides free and cashless services to pregnant women for routine deliveries, caesarean operations and sick newborn care, including free transport from home to health institutions, between health facilities in case of referral, and from health facility to home,Citation24 and Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), a conditional cash transfer scheme to increase institutional delivery, were implemented nationwide.Citation25,Citation26 Concurrently, community health workers known as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) were inducted to increase community engagement with the health system and support access to public health services.Citation27 Village Health and Nutrition Days (VHND) began to be implemented monthly to provide primary health care services at village level, including distribution of contraceptives, and conducting antenatal and postnatal services.Citation28 The Integrated Child Development Services, a flagship programme for supplementary nutrition of young children and pregnant and lactating women, has also been in place nationwide; under this programme, rural childcare centres known as Anganwadi Centres are run by community nutrition workers or Anganwadi workers.Citation29 In addition to this, guidelines exist for ASHA outreach among populations facing marginalisation due to geographic, cultural, caste, and other social barriers,Citation30 although even here, guidelines for specific outreach to displaced people do not exist. Overall, to date, very little research has explored displaced women’s RMH needs or experiences in accessing these services, a gap our study intended to fill.

Methodology

As part of a larger qualitative exploratory study in conflict-affected districts and among displaced populations in the North-East region of India, we approached Bru displaced women to understand the impact of displacement on their RMH service utilisation. We conducted focus group discussions (FGDs), and unstructured in-depth interviews with Bru displaced women and community health workers, known as ASHAs, in camps located in two sub-divisions – Kanchanpur and Panisagar – in Tripura state. The camps where Bru displaced people were living were purposively selected to cover at least one camp in each sub-division. The names of the camps have been withheld to maintain anonymity.

Before data collection, the lead author (PR) visited the camps in each sub-division to assess the situation and seek cooperation from the community. PR held discussions in one camp to ascertain the ease of recruitment, comprehension, and the need for modification of the interview guide, while meetings were conducted with the state health officials for their approval and cooperation.

Institutional Review Board approval was granted by the Public Health Foundation of India’s Ethics Committee (TRC-IEC-329/17) on 21/3/2017.

Data collection

We carried out field-based data collection with married and unmarried Bru displaced women of reproductive age (18–45 years) between June and July 2018. A total of four FGDs with 8–10 women in each group were conducted across three camps by a team comprising PR and an experienced field investigator from the Reang tribal community belonging to Tripura state. Reang is a local tribe in Tripura that speaks the same dialect as Bru displaced people from Mizoram. The field investigator was oriented with the study objectives, interview guide, and ethical considerations by PR before commencing data collection.

Before each group discussion, the team visited the camps to schedule discussions. In all selected camps, the help of women residing in that camp was sought to recruit their peers. The FGDs were conducted to explore and understand shared perspectives on women’s reproductive health and their experience of utilising services. The purpose of the study and its ethical aspects were explained to participants. On acceptance to participate, the participant information sheet was read out and written or verbal informed consent was obtained.

Consent from each participant was taken to conduct and record the discussion. If any woman had a query, the research team addressed it before starting the discussion. Questions were related to socio-demographics, maternal health (i.e. pregnancy and childbirth), as well as reproductive health (i.e. family planning and abortion care). In the case of six FGD participants, we noted that there were unique experiences related to our topic that could not be probed adequately in the FGDs. We therefore sought separate consent for individual follow-up interviews with these participants. Further information related to pregnancy care, family planning, and abortion was documented in detail using an open-ended interview at their residence, at their convenience. All group discussions and interviews were facilitated in the local Reang dialect.

We also interviewed five purposively selected ASHAs working in the selected camp. Sampling was aimed at achieving data saturation. Interviews with ASHAs focused on their experience of providing maternal and reproductive health services in the camps.

Data management and analysis

After each day, field notes were written by the lead author and discussed with a field investigator for her observation and inputs. All digital recordings of FGDs and interviews were kept in a folder accessible to the research team. Each recording was transcribed verbatim by a transcriber belonging to the Reang tribe. All transcripts were translated from local dialects into English and checked for consistency, although we could not compare transcripts with the audio-recording due to constraints in language proficiency in the core team. Transcripts were cleaned and analysis was done using Atlas. ti 8.

An inductive conceptual framework was developed for a larger study using a grounded theory approach.Citation31 All three authors familiarised themselves with the data by reading and coding transcripts independently. A codebook was prepared based on the first perusal of data by each of the coders. This was followed by an iterative process comprising three rounds of discussion on coding to build consensus on all codes used. Codes were then applied across the dataset by each of the researchers. Project bundles were shared by AS and DN and merged by PR to carry out selective coding, bringing together data into code categories and meta-categories. Further rounds of discussion resulted in inductive and deductive grouping of codes to cover various aspects of RMH, corresponding to, but not limited by, our initial conceptual framework. For this paper, we chose to focus on the three RMH areas of maternal health, abortion, and family planning services and used these domain areas to index categories using a deductive approach (see Supplemental File 1). Indexed codes were then perused and presented in narrative format for this paper.

Results

Participant profile

A total of 49 displaced women took part in discussions; of these, 43 were married. A majority (33 of 49) of the women had never gone to school and were working as daily wage earners. Self-employed women reported selling groceries at a shop inside the camp. Women working as daily wage earners were engaged in informal sector work in brick kilns, load-bearing and contractor-designated tasks on construction sites, as well as selling vegetables and firewood in the local market. They noted that they travelled daily in search of work and did whatever task they could find. summarises the participants’ profiles.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

The five ASHAs interviewed were also from the Bru displaced community and were living in the camps. All were married and working as ASHAs since 2008. They had all been trained by the Tripura state health system and were rendering services as per the national guidelines of RMNCH + A and JSY. These guidelines were used as their reference point to provide RMH services in their catchment areas, which included IDPs, as there were no separate guidelines or programme for IDPs.

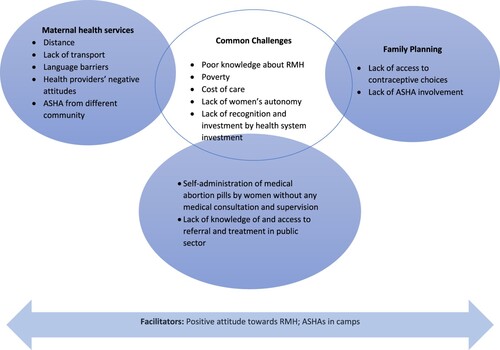

Women reported a range of service utilisation experiences and challenges related to maternal health care, family planning, and abortion services (see ).

Maternal health care

Women across the four groups felt that good nutrition and adequate rest are required during pregnancy but also noted that this was not feasible for them due to poverty. They further noted that in their culture, there were no food restrictions during pregnancy and that pregnant women could eat anything, provided the family could afford it. They mentioned that a pregnant woman would like to eat “many things” but could not afford them. Bamboo shoots were a staple as they could be sourced from the jungle with relative ease and no expense (this was offered to us during fieldwork as well). Other vegetables were eaten whenever families could afford them. One of our interviewees, a pregnant woman who had skipped dinner, explained:

“What can we say? I am pregnant and I still have to go and fetch water, carry firewood. Sometimes I am in pain and suffer and still, I have to do my work. What to do? Sometimes I want to eat good food, nutritious food, but we cannot afford it, as we are poor … (Laughs). These are the problems. There are so many problems, innumerable problems … ” [Focus Group Discussion]

Similarly, not accessing health facilities during pregnancy for antenatal and postnatal care was common across camps. No more than four of the 49 women participating in FGDs reported that they went for a check-up during pregnancy and even those who did could not articulate why this was important. We found that participants were not aware of many of the RMH services prescribed in the national health programme. For example, women noted that adequate rest and care during pregnancy is important, but they were not aware of the need for antenatal and postnatal check-up. There was a lack of knowledge and awareness about why antenatal and post-natal check-up was important, but once probed on the acceptability of such services if available, all participants expressed their willingness to go for check-ups during pregnancy. Illiteracy and poor knowledge among women and their families about the importance of seeking care during pregnancy were other factors that ASHAs linked to poor service utilisation. For example, in one group a woman mentioned that an ASHA gave her iron-folic acid tablets during pregnancy, which she initially consumed but eventually discontinued as she associated them with blisters that appeared on her tongue at the time.

Participants also noted that they prioritised check-ups during pregnancy only if the pain or problem was severe and unbearable. On several occasions, such issues were neglected due to poverty and household responsibilities. For example, a pregnant woman in one group reported that she had numbness in her legs and hands, and she fainted a few times but did not consult a doctor because of lack of money and distance from the health facility. Another pregnant woman suffering from severe body ache and swollen feet noted:

“Right now, I am four months into pregnancy, but I am unable to go for a medical check-up. Even others [friends] are advising me to go and see a doctor for pregnancy check-up so on and so forth, but I am unable to go due to financial problems. This is the condition.” [Focus Group Discussion]

Of course, hospital delivery. We would prefer a hospital …

We would like to deliver at a hospital, but we do not have money. Therefore, we cannot afford to deliver at a hospital. Without money, we cannot. We can opt to deliver at a hospital or go to a doctor for consultation, only if we have money. My body aches, headache, dizziness all these problems I want to get treated by the doctor …

Without money, we cannot go to the hospital for delivery. Here we are unable to sustain properly, how can we go to a hospital? If we die, then that’s it, we die here, at home. We have to deliver at home. [Focus Group Discussion]

Besides this, a range of challenges, related to availability, accessibility, acceptability, affordability, and other dimensions was seen, often in a complex, interconnected fashion. We inferred from our fieldwork with participants that there was no effort by the health system to include or reach out to displaced Bru women with existing RMH services or to meet their needs. If pregnant women visited the primary health centre (PHC), then antenatal care would be carried out, but no specific effort was made to cover all pregnant women across camps for the service. Study participants and ASHAs mentioned that off and on – i.e. once a month or after many months – health camps were organised by the local health system, particularly for immunising children or to mitigate outbreaks. However, other services such as antenatal and postnatal care were not included in these ambulatory services.

Accessing a health facility for maternal health services was additionally challenged by distance as well as lack/cost of transport. The nearest PHC was situated near the settlement of the local population in Tripura. For camp dwellers to access this facility, the primary route would be to walk or hire a private vehicle, since public transport was not available. The cost of hiring a private vehicle, ranging between INR 2000 and INR 5000 [US$ 26 and 66], was a major deterrent for communities because most were in daily wage labour and this would hollow out monthly earnings substantially. Participants reported that women were, therefore, opting for delivery at home despite their willingness to have institutional births. They further said that they were leading an onerous life, which required resourcefulness and courage.

“Of course, we have to spend … Since we have to book the car and go to the hospital and also during delivery we have to pay for the doctor. And we have to pay for the vehicle fare also … More than 2000–3000 rupees [US$ 26–40] and up to 4000–5000 rupees [US$ 53–66] like that. It is up to us to reserve the vehicle and go, and again reserve the vehicle to come back home.” [Focus Group Discussion]

“Due to poverty, it is very difficult. It is very pitiful sometimes. For two-three days they [pregnant women] have to [suffer] prolonged labour and we have to watch and look after them also … These are things. Since there’s no money, they cannot go [to a hospital for delivery]. This is because of poverty. Family members of pregnant women feel helpless of not being able to do anything after seeing her go through the pain [because of not having the money to take her to the health facility].” [ASHA, in-person interview]

We don’t understand. The person [ASHA] speaks in Bengali language, and we fail to understand what she is saying, and, she doesn’t visit us.

She doesn’t visit you?

The person [ASHA] cares only for those who go to her. She doesn’t even try to care [for us]. If we go to her, then only we get some help otherwise she doesn’t [care]. If we inform her then only, she will visit us. She doesn’t visit [the camp] to know whether there is a pregnant woman. She doesn’t care. [Focus Group Discussion]

“When I went to the doctor, at that moment the doctor was unwilling to do my check-up. He said that he was too tired to do any check-up. However, my ASHA, she insisted him do the examination as I will not be able to come back again for the examination. It seems the doctor was inattentive towards me. When their people [local community belonging to Tripura state] came they were given priority, whereas I got the last opportunity. I want to narrate all these things because what I am saying is the truth.” [Focus Group Discussion]

Women in a camp reported that the availability of ASHAs had reduced maternal deaths. For example, in one FGD it was raised that earlier many pregnant women died due to complications during delivery because of poor access to skilled health care providers, but after the engagement of ASHAs, the scenario had changed:

“Now, ASHAs come and check [pregnant women]. They come and do a little bit of check-up. If someone is in labour, then the ASHA arranges vehicle and helps, that’s one of the reasons. Otherwise, it [maternal deaths] would have happened just like earlier days. Many [women] would have died during delivery.” [Focus Group Discussion]

Family planning

Most of the women were aware of traditional methods such as rhythm and withdrawal, and names of oral contraceptive pills (OCP) such as Mala N, Mala D, Choice, and Sukhi-Parivar [i.e. Happy Family] for birth spacing. Only two women in one group were aware of female sterilisation and Copper T methods. Women were also aware of male condoms, but emergency contraception was largely unheard of. Moreover, fewer than four out of the 49 women were aware of injectable birth control. The main sources of reproductive health information were private pharmacists and participants’ female friends. A few women in two groups also noted ASHAs as the source of information.

I want to stop conceiving. But thus far I have not taken any step as to what to do, I have no plan.

So, to stop conceiving, do you know any procedures or methods?

No, I do not know. [Focus Group Discussion]

We found that OCPs were the most preferred method for birth spacing as they were easily available at the private pharmacy without a prescription or a doctor’s consultation. A woman in a group mentioned that she had been using OCPs for the last 10 years to avoid pregnancy. A few women were consuming pills that they were told were OCPs; as one woman explained: “since we cannot read, we don’t know the name of the medicine. They [the pharmacist] told us that it is a contraceptive pill and we are purchasing it.” Another woman mentioned that for almost 15 years she had been taking OCPs without knowing its name but had become familiar with the packaging over time.

In addition to being accessible in private pharmacies, OCPs were reported to be affordable. The cost of one pack of OCP (i.e. for a month) was INR 20 [roughly US$ 0.3]. While most of the women reported purchasing OCPs from a private pharmacy, a few women reported receiving it from ASHAs in the camps for free.

A few women also mentioned using traditional methods of birth spacing such as withdrawal, rhythm, and abstinence. Only two women mentioned that they took an injection to prevent pregnancy for six months. The injection was easily available at a private pharmacy; each injection to prevent pregnancy (biannually) was INR 100 [US$ 1.3]. Besides this, women informed that the use of condoms was not preferred by husband and a woman noted “it [condom] is for men only, not for women. If men don’t use it then we don’t [insist]. We have to follow our husbands’ wish.”

Across camps, there was unmet need for birth spacing and permanent methods. Lack of access to contraceptive choices other than OCPs and traditional methods along with poor knowledge and misconception were major challenges. We also found that ASHAs were not involved with activities to improve women’s knowledge about various family planning methods such as the intrauterine device (IUD), emergency contraceptive pills, vasectomy, and tubal ligation and its availability at public health facilities. Concurrently, women did not feel they had the autonomy to plan a family or insist their husbands use condoms to avoid unwanted pregnancies. All these factors were influencing poor utilisation of contraceptive methods and family planning in the camps.

Abortion

Women openly discussed abortion once they were further along in the FGD. For example, in one FGD, women were reluctant to discuss this topic in the beginning, saying that they were not aware of the termination of pregnancy, but later, in the same discussion, this topic was reprised and discussed. There were mixed attitudes toward abortion. While some noted that it was commonly practised and an option for terminating pregnancies, a few women noted that abortion was against their religious beliefs. This belief was described by a woman in a group: “Even if we are pregnant by mistake, we consider that God has given us [the child]. So, we keep the child, even though we might face struggles and problems.” [Focus Group Discussion]

Participants noted that they were aware of women in the camps either using medical abortion through pills obtained directly from pharmacies without doctor’s prescription or having a procedure at a private health facility in the specific case of teenage pregnancy. Women conveyed that pregnancy could be terminated at private health facilities and that pills for medical abortion were available at private pharmacies (without a doctor’s prescription) but only one woman across groups reported using the latter. In addition, a few women believed that taking pills for medical abortion could lead to vaginal bleeding or death, and one woman in a group discussion reported discomfort and uneasiness after using pills for medical abortion (detailed in Box 1). The death of a few women was attributed by participants in one camp to medical abortion pills, while ASHAs in another camp suggested that these deaths were due to improper treatment.

Reena [name changed], aged 32 years, and living in a camp, was taking contraceptive pills to prevent pregnancy but got pregnant for the fourth time. Since Reena did not want this pregnancy, she consulted a pharmacist in a friend’s father’s shop. The pharmacist gave her a strip of pills that he said would work for medical abortion, costing INR. 180 [US$ 2}. She took the pills, but nothing happened. She waited for a month and again visited the shop. The pharmacist gave her more pills and told Reena that this time it will work. As per the pharmacist’s instruction, Reena took the pills. She had light bleeding which eventually stopped.

During discussion, Reena complained of no fetal movement but a lump inside the womb, difficulty in passing urine and a burning sensation. She also complained of restlessness, stomach cramps, severe body ache and nausea throughout the day. She was worried and did not know what to do.

When asked why she did not consult a doctor before taking the pills, Reena mentioned she did not have enough money for a doctor’s consultation. Further, she had seen many women in the camp using medical abortion pills and therefore decided to try them.

[After the FGD, with Reena’s consent we took her to the nearest government hospital where the procedure was successfully carried out by a gynaecologist].

The use of medical abortion through pills obtained from private pharmacies was reportedly higher, as they were easily available and cheaper than visiting a private doctor. Participants noted that the cost of abortion at a private hospital, between INR 2000 and 3000 (US$ 26–40), was a deterrent, while medical abortion cost between INR 400 and 600 [US$ 5–8] at a pharmacy, which some women preferred. A doctor was visited only if the medical abortion pill was not effective or the pregnancy was past the stage when such medication would work. We found that participants were not aware of the availability of abortion services at public health facilities and always went to the private sector. As such, abortion always involved expenditure:

Usually most of us take this 500 or 600 rupees medicine, and after that, we used to go to the [private] hospital …

And due to some reasons, if the abortion becomes complicated and incomplete, the blood flow doesn’t stop, resulting in stomach-ache …

We have to wash [abort] … .

We have to go to the hospital and tell the doctor to wash the fetus, that’s how we abort the child. [Focus Group Discussion]

Discussion

This study is part of our effort to bring out internally displaced women’s experiences and challenges faced while accessing RMH services. To our knowledge, this is the first such attempt in India. It is noteworthy to mention that the challenges highlighted in this study – such as lack of transportation, cost of care, lack of women’s autonomy and accessing private pharmacies for RMH services – are not unique to Bru IDPs and can be compared to displaced women in other states, or marginalised groups such as migrant workers and isolated tribal communities in India.Citation32,Citation33 However, given that the Bru women are displaced, the likelihood of these needs being recognised and met by the health system was found to be lower, even though they did have access to ASHAs and some health services in both the public and private sector.

Among Bru displaced women, we found limited knowledge about RMH but positive attitudes towards pregnancy care, institutional delivery, and family planning: women were willing to use these services. Ironically, this positive attitude did not translate into practice due to the interaction of individual, social, and health systems factors like lack of knowledge, poverty, and inaccessibility of services. The influence of these factors was evident when women reported how limited their family planning options were in practice, and that they continued to have a high rate of home deliveries in camps despite wanting contraceptive choice and institutional delivery. Encouragingly, women knew about OCP for birth spacing but most of them were not aware of emergency contraceptive pills or permanent methods such as sterilisation as options. Myths and fear were major barriers to the uptake of intra-uterine contraceptive devices, a finding seen elsewhere in India and a domain where efforts to improve health provider communication have been explored.Citation34

Apart from limited knowledge, displaced women faced numerous challenges in accessing care due to distance, cost of transportation, and care-seeking expenses. Women had access to public health facilities of the hosting state and were not restricted from using them. Moreover, Tripura had selected and trained ASHAs in each camp. However, we found that ASHA support was limited to pregnancy care and childbirth. There is a need for additional and tailored efforts which can be sustained and adapted in the context of the situation of displaced women.Citation35 There are examples where countries like Myanmar have implemented Mobile Obstetric Maternal (MOM) Health Workers to increase access to reproductive health services among displaced women.Citation36 Adaptation of such initiatives could be a significant step as the camps are in remote locations, but care must be taken to ensure that the initiatives in the community are not limited to pregnancy care and childbirth, and address women’s needs outside motherhood.

Many existing services implemented by the hosting state for its residents – if actively extended to include displaced communities – could likely make a big difference. For instance, monthly Village Health and Nutrition Days could be organised in the camps just as they are being implemented in villages across India.Citation28 Camps also have churches with women’s groups that could support this. Considering that women in the FGDs noted the importance of good nutrition during pregnancy, this platform could also be used for distributing take-home rations to pregnant women and nursing mothers under the Integrated Child Development Services.Citation29

Greater effort should be made to include displaced pregnant women in the JSSK scheme, to comprehensively address the specific barriers that women have indicated, related to the cost of transport, drugs, and supplies. An immediate step, emerging in our data, would be to facilitate the opening of bank accounts so that benefits may be received. Such an initiative would also build trust in the community towards ASHAs and the health system. Concurrently, efforts must be put in place to ensure greater outreach to IDPs under the national health insurance scheme, the PMJAY.Citation21 This would be an important step, as women in our study repeatedly mentioned the financial burden as a major barrier to accessing health services.

Another important barrier was discrimination towards Bru displaced women by health providers at health facilities. The sense of alienation was heightened in cases where ASHAs did not belong to the Bru community in all camps. Reducing discrimination at health facilities will require the health system to sensitise health providers and ensure respectful behaviour towards all patients in observance of the Respectful Maternity Care Charter and other global norms.Citation37 The approach of selecting ASHAs directly from communities, which has been tried all over India, including in remote tribal areas, certainly plays a role in addressing language and cultural barriers, and could potentially help to reduce discrimination.Citation38 Additionally, our findings suggest there is scope for engaging displaced women as educator facilitators in seeking and promoting care. In sub-Saharan Africa, refugee laywomen have been trained to provide health education, referrals, and contraceptives for their communities.Citation39 Our research has shown engagement of ASHAs to be beneficial; placing emphasis on this and engaging displaced women as peer educators will enable the development of culturally acceptable, participatory communication strategies for generating RMH literacy amongst displaced women and men as well as extending existing schemes.

We also found that displaced men are important stakeholders in decisions about the site of delivery and family planning. Evidence suggests there have been improvements in maternal and newborn health care-seeking and home care practices after engaging men in maternal and newborn health.Citation40,Citation41 In the case of this population, culturally appropriate approaches would have to be determined and pursued alongside those described above so as not to introduce greater risk for women.

Our study also revealed the need for RMH services offered through an approach that gives importance not only to specific health outcomes but also to the underlying determinants that drive inequities and deprivation of rights.Citation42,Citation43 In our study, we found that poverty, and women’s position in decision-making concerning institutional births and family planning, along with the underlying health care determinants – availability, accessibility, affordability, and acceptability – are driving the decision to use or not to use the RMH services. This is similar to the challenges faced by internally displaced women in other contexts, such as in a number of African countries.Citation8 Other barriers, like poverty, food insecurity, and health service access, are reported in other South Asian countries such as Pakistan and Afghanistan as well as some African countries.Citation3,Citation8 It is critical to address these root causes within and outside health systems.Citation43 In the Indian context, future research should explore in greater detail aspects like household decision-making and access to resources, as well as experiences of discrimination beyond the health sector among displaced communities, which may help identify entry-points to ensure that interventions reach them.Citation44

It is imperative for India to first recognise and commit towards IDPs and incorporate the RMH service needs of displaced women in policies and programmes, in the true spirit of universality. Currently, the situation of such groups is neither acknowledged nor catered for in national or state guidelines and institutions working towards improving women’s health. Our study has shown the value and great relevance of existing policies for these populations on the one hand, and the need to extend and adapt them to ensure that they are effective for displaced populations, on the other. Women in displaced communities can be partners in such an effort, as our study revealed; their interest and stakes are high and global norms point towards the need to use an approach of accountability to the people affected.Citation45

Other factors such as lack of financial resources, uncertainty about the future and prevailing insecurity, and their influence on women’s health, cannot be ignored. During our interactions with displaced women, these factors were brought up repeatedly and this corroborates findings from other settings where it was found that most of the problems of displacement were connected with income and socio-ecological factors.Citation1,Citation8,Citation13,Citation46 In our setting, camps were located in remote locations where national income generation schemes were not in place or functioning; this resulted in situations of protracted financial insecurity for displaced people. This lack of economic activity was compounded by the monetisation of RMH health-seeking (purchased in the private sector, given the absence of outreach of the public sector), which further reduced health care access for displaced people. Our findings suggest that a broader programme of skill-building and vocational training to address the larger livelihood issues and financial constraints of IDP could have knock-on effects on RMH. Beyond RMH, action on these broader social determinants could safeguard the health and wellbeing of displaced women in the longer term.

Limitations

We were unable to cover other components of reproductive health such as domestic and sexual violence as women were not open to discussing this topic, and the field investigator lacked expertise and experience in probing such a sensitive issue. This study also did not capture intra-household dynamics or displaced men’s perspectives about women’s RMH, which are key areas of future work. We were unable to explore in depth the health systems barriers in providing RMH among displaced women. We have described challenges faced by women originally displaced by conflict but who have been living in camps in non-conflict settings for more than 20 years; these findings may not all be relevant for women who have been recently displaced within or outside the state. Women living in protracted displacement and in camps have different challenges, needs, and risks as they are deprived of adequate shelter, food, and health services compared to women living in host villages.

Another limitation of our study was that we included married and unmarried women in the same FGDs. As a result, the two unmarried women felt they could not contribute to questions on maternal health and family planning and some of the themes could not be adequately probed with either. Future research should consider these and other subgroups of women who may have distinct as well as shared care needs and pathways.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that there is a positive attitude towards RMH among Bru displaced women and scope for engaging women to improve their utilisation of maternal health, family planning and abortion services. There is a need to address financial barriers to improve access to care, reduce access barriers by extending and expanding the scope of existing services, and ensuring that frontline health workers truly represent and respect displaced persons. Involvement of the community is desirable from a rights-based perspective as well as to ensure accountability and the feasibility of such interventions.

Authors’ contributions

PR led the study design, data collection, and analysis, conceptualised and drafted the manuscript. DN and AS participated in study design, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of the World Food Programme.

Supplemental File 1

Download MS Word (25.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants in this study for giving their time and sharing their experiences. The authors acknowledge the contribution of Ratna Reang (during data collection) and Purni Biswas (throughout the study). We would also like to thank Rev Nangsarai Reang and Rev. Devidson for helping us with the translation of interview guides. We gratefully acknowledge the support received from the Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Tripura, Dr Ashok Roy and Arindam Saha. We are also grateful to the Centre for North-East Studies and Policy Research, Guwahati for their support during the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Burns R, Wickramage K, Musah A, et al. Health status of returning refugees, internally displaced persons, and the host community in a post-conflict district in northern Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional survey. Confl Health. 2018;12(41):1–12.

- Thomas SL, Thomas SDM. Displacement and health. Br Med Bull. 2004;69:115–127.

- David S, Gazi R, Mirzazada MS, et al. Conflict in South Asia and its impact on health. Br Med J. 2017;357(j1537):1–5.

- IDMC. Global report on internal displacement- South Asia [Internet]. Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 7] p. 47–51. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2020/downloads/2020-IDMC-GRID-south-asia.pdf?v=1.17

- UNHCR. Internally displaced people [Internet]. (2020) [cited 2020 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/internally-displaced-people.html

- Beyani C. Improving the protection of internally displaced women:Assessment of progress and challenges [Internet]. USA: Brookings Institution. 2014. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Improving-the-Protection-of-Internally-https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Improving-the-Protection-of-Internally-Displacement-Women-October-10-2014.pdfDisplacement-Women-October-10-2014.pdf

- Albuja S, Arnaud E, Beytrison F, et al. Global overview 2012 : people internally displaced by conflict and violence [Internet]. Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Norwegian Refugee Council; 2013 [cited 2016 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/global-overview-2012-people-internally-displaced-by-conflict-and-violence

- Amodu O, Richter M, Salami B. A scoping review of the health of conflict-induced internally displaced women in Africa. Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1280.

- Ketkar P. Internal displacement in South Asia [Internet]. Available from: http://www.ipcs.org/ipcs_books_selreviews.php?recNo=211

- UNHCR. Guiding principles on internal displacement [Internet]. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2004 [cited 2021 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/idps/43ce1cff2/guiding-principles-internal-displacement.html

- UNHCR. Women [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/women.html

- Cazabat C, Andre C, Fung V, et al. Women and girls in displacement. Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre; 2018.

- Medecins Sans Frontieres. Forced to flee-Women’s health and displacement [Internet]. Medecins Sans Frontieres; [cited 2018 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.msf.org/forced-flee-womens-health-and-displacement

- Center for Repdroductive Rights. Ensuring sexual and reproductive health and rights of women and girls affected by conflict [Internet]. United States. 2017 [cited 2020 Mar 27]. Available from: https://reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/documents/ga_bp_conflictncrisis_2017_07_25.pdf

- IDMC. Global report on internal displacement [Internet]. Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 5] p. 159. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/2019-IDMC-GRID.pdf

- Sharma SK. Displaced Brus from Mizoram in Tripura: time for Resolution [Internet]. New Delhi: Vivekananda International Foundation. 2017. Available from: https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/Displaced-Brus-from-Mizoramin-Tripura-Time-for-Resolution.pdf

- Press Trust of India. Centre to withdraw assistance to Bru relief camps from Oct 1. Business Standard [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Dec 3]; Available from: https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/centre-to-withdraw-assistance-to-bru-relief-camps-from-oct-1-118091100121_1.html

- The New Indian Express. Ration supply resumed for Bru refugees till March. The New Indian Express [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 3]; Available from: https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2019/jan/16/ration-supply-resumed-for-bru-refugees-till-march-1925778.html

- Halliday A. Poor conditions in camps, Bru leaders say Tripura “want us to leave” [Internet]. The Indian Express. 2014. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/poor-conditions-in-camps-bru-leaders-say-mizoram-wants-us-to-leave/

- Ministry of Rural Development. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. 2005. [Internet]. Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India; 2017 [cited 2020 Nov 21]. Available from: https://nrega.nic.in/amendments_2005_2018.pdf

- Government of India. About Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.pmjay.gov.in/about/pmjay

- United Nations. Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/

- National Health Mission. Reproductive child health [Internet]. Reproductive and Child Health Portal. 2017 [cited 2020 Mar 15]. Available from: https://rch.gov.in/reproductive-child-health-rch

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. A strategic approach to reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (RMNCH + A) in India [Internet]. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2013 [cited 2020 Feb 15]. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/RMNCH+A/RMNCH+A_Strategy.pdf

- MoHFW. Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram (JSSK) [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/janani-shishu-suraksha-karyakaram-jssk_pg

- MoHFW. Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) [Internet]. Delhi. 2015. [cited 2021 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/janani-suraksha-yojana-jsy-_pg

- Agarwal S, Curtis SL, Angeles G, et al. The impact of India’s accredited social health acitivit (ASHA) program on the utilization of maternity services: a nationally representative longitudinal modelling study. Hum Resour Health. 2019 Aug 19;17(68):1–13.

- National Rural Health Mission. Village health nutrition day [Internet]. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2007. [cited 2020 Apr 20]. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/communitisation/vhnd/vhnd_guidelines.pdf

- Press Information Bureau M of H and FW Government of India. Contract workers employed in NRHM [Internet]. 2014. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=107163

- NRHM. The eight fold path [Internet]. National Rural Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; [cited 2021 Oct 7]. Available from: https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Reaching%20The%20Unreached%20Brochure%20for%20ASHA%20.pdf

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publication Inc; 2006.

- Hazarika S. Strangers no more: new narratives from India’s Northeast. Delhi: Aleph book company; 2018.

- Contractor SQ, Das A, Dasgupta J, et al. Beyond the template: the needs of tribal women and their experiences with maternity services in Odisha. India Int J Equity Health [Internet]; 17(134). Available from: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12939-018-0850-9

- Mishra N, Panda M, Pyne S, et al. Barriers and enablers to adoption of intrauterine device as a contraceptive method: a multi-stakeholder perspective. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2017;6(3):616–621.

- Warren E, Post N, Hossain M, et al. Systematic review of the evidence on the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health interventions in humanitarian crises. BMJ Open; 5:e008226.

- Mullany L, Catherine L, Paw P, et al. The MOM project: delivering maternal health services among internally displaced populations in Eastern Burma. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31):44–56.

- White Ribbon Alliance. Respectful maternity care: the universal rights of childbearing women [Internet]. The White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood; [cited 2020 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/woman_child_accountability/ierg/reports/2012_01S_Respectful_Maternity_Care_Charter_The_Universal_Rights_of_Childbearing_Women.pdf

- Nambiar D, Seshadri T, Pari V, et al. Enhancing the role of community health workers in service utilization of tribal populations: an implementation research study [ unpublished project report]. Delhi: George Institute for Global Health; 2021.

- Woodward A, Howard N, Souare Y, et al. Reproductive health for refugees by refugees in Guinea IV: peer education and HIV knowledge, attitudes, and reported practices. Confl Health. 2011;5(1):10.

- Fhi 360. Increasing men’s engagement to improve family planning programs in South Asia [Internet]. Fhi 360. 2012. [cited 2020 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.fhi360.org/resource/increasing-mens-engagement-improve-family-planning-programs-south-asia

- Tokhi M, Thomson LC, Davis J, et al. Involving men to improve maternal and newborn health: a systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191620.

- World Health Organization, United Nations Human Rights. A human rights-based approach to health [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2009. [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/hrba-to-health-en.pdf?ua=1

- Yamin A. From ideals to tools: applying human rights to maternal health. Plos Med. 2015;10(11):e1001546.

- United Nations Population Fund. The human rights-based approach [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/human-rights-based-approach

- UNICEF. Summary guidelines to integrating accountability to affected people (AAP) into country office planning cycles [Internet]. Kenya; 2020 [cited 2021 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/7101/file/UNICEF-ESA-Intergrating-AAP-2020.pdf.pdf

- Ali Hirani S, Richter S. Maternal and child health during forced displacement. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019;51(3):252–261.