Abstract

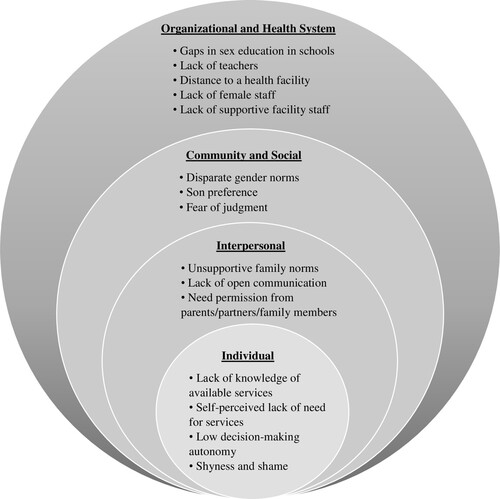

Adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries continue to face poor sexual and reproductive health (SRH). In Nepal, early marriage and motherhood, gender-based violence, and unmet need for contraception remain pervasive. Adolescent girls in rural areas bear a disproportionate burden of poor reproductive health outcomes, but there are limited context-specific data. This is a qualitative study to identify factors that impact adolescent girls’ utilisation of and access to SRH services in a rural district of Nepal. We conducted 21 individual interviews with adolescent girls aged 15–19 years, and three focus group discussions with community health workers. We used an inductive analytic approach to identify emergent and recurrent themes and present the themes using the social ecological model. Individual-level factors that contribute to low uptake of services among adolescent girls include lack of knowledge, self-perceived lack of need, low decision-making autonomy, and shyness. Interpersonal factors that impact access include unsupportive family norms, absence of open communication, and need for permission from family members to access care. At the community level, disparate gender norms, son preference, and judgment by community members affect adolescent SRH. Inadequate sex education, far travel distance to facilities, lack of female healthcare providers and teachers, and inability to access abortion services were identified as organisational and systems barriers. Stigma was a factor cross-cutting several levels. Our findings suggest the need for multi-level strategies to address these factors to improve adolescent girls’ SRH.

Résumé

Dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire, les adolescentes continuent de souffrir d’une mauvaise santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR). Au Népal, les mariages et les maternités précoces, la violence sexiste et les besoins insatisfaits de contraception restent très répandus. Les adolescentes qui vivent en zone rurale supportent une charge anormalement importante de mauvaise santé reproductive, pourtant, les données spécifiques au contexte sont limitées. Cette étude qualitative souhaite identifier les facteurs qui influencent l’accès et le recours des adolescentes aux services de SSR dans un district rural du Népal. Nous avons mené 21 entretiens individuels avec des adolescentes âgées de 15 à 19 ans et trois discussions par groupe d’intérêt avec des agents de santé communautaires. Nous avons utilisé une approche analytique inductive pour identifier les questions émergentes et récurrentes et présenter les thèmes à l’aide du modèle écologique social. Les facteurs au niveau individuel qui contribuent à un faible recours aux services chez les adolescentes incluent le manque de connaissances, l’impression de ne pas avoir besoin de ces services, la faible autonomie dans la prise de décision et la timidité. Les facteurs interpersonnels qui influent sur l’accès incluent les normes familiales qui ne soutiennent pas les adolescentes, l’absence de communication ouverte et la nécessité d’obtenir la permission des membres de la famille pour bénéficier des soins. Au niveau communautaire, les normes de genre disparates, la préférence pour les fils et le jugement par les membres de la communauté touchent la SSR des adolescentes. Une éducation sexuelle inadaptée, l’éloignement des centres, le manque de personnel féminin chez les prestataires de soins de santé et les enseignants, ainsi que l’impossibilité d’avoir accès aux services d’avortement ont été identifiés comme des obstacles organisationnels et systémiques. La stigmatisation était un facteur commun à plusieurs niveaux. Nos conclusions suggèrent la nécessité d’adopter des stratégies à multiples niveaux pour s’attaquer à ces facteurs et améliorer ainsi la SSR des adolescentes.

Resumen

En los países de bajos y medianos ingresos, las adolescentes continúan enfrentando salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) deficiente. En Nepal, el matrimonio y la maternidad precoces, la violencia de género y la necesidad insatisfecha de anticoncepción permanecen omnipresentes. En las zonas rurales, las adolescentes sufren de manera desproporcionada los malos resultados relacionados con la salud reproductiva, pero hay datos limitados sobre cada contexto específico. Este estudio cualitativo pretende identificar los factores que afectan el uso de los servicios de SSR por las adolescentes y su acceso a dichos servicios en un distrito rural de Nepal. Realizamos 21 entrevistas individuales con adolescentes de 15 a 19 años y tres discusiones en grupos focales con agentes de salud comunitaria. Utilizamos un enfoque de análisis inductivo para identificar temas emergentes y recurrentes y presentar los temas utilizando el modelo ecológico social. Los factores individuales que contribuyen al bajo nivel de aceptación de los servicios entre las adolescentes son: falta de conocimiento, carencia de necesidad autopercibida, poca autonomía para tomar decisiones y timidez. Los factores interpersonales que afectan el acceso son: normas familiares insolidarias, carencia de comunicación abierta y la necesidad de obtener el permiso de un miembro de la familia para acceder a los servicios. A nivel comunitario, las normas de género dispares, la preferencia por hijo varón y ser juzgada por integrantes de la comunidad afectan la SSR adolescente. Se identificaron como barreras institucionales y sistémicas la educación sexual inadecuada, las largas distancias de viaje a establecimientos de salud, la falta de mujeres prestadoras de servicios de salud y maestras, y la imposibilidad de acceder a los servicios de aborto. El estigma es un factor transversal en varios niveles. Nuestros hallazgos indican la necesidad de formular estrategias de múltiples niveles para abordar estos factores con el fin de mejorar la SSR de las adolescentes.

Background

Despite positive trends in adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) in the last 25 years, girls in low- and middle-income countries, including Nepal, continue to bear a disproportionate burden of poor health outcomes.Citation1 Adolescent girls in Nepal face challenges such as gender-based violence, early marriage and motherhood, menstrual banishment and restrictions, and limited economic opportunities that impact their SRH.Citation2,Citation3 Data from 2016 showed 27% of adolescent girls in Nepal aged 15–19 were married, and 17% have been pregnant.Citation4 Early childbearing was associated with lower socioeconomic status, less education, and contraceptive non-use.Citation5,Citation6 Overall, contraceptive use among adolescents in Nepal remains low. Fifteen per cent of married girls aged 15–19 use any modern contraceptive method and approximately 35% of them have an unmet need for contraception.Citation4 Only 42% of adolescents aged 15–19 are aware that abortion is legal in Nepal.Citation4 Studies have identified geographic challenges, transportation, cost, and supply-side constraints such as providers’ lack of knowledge, limited opening hours, and waiting times as barriers to utilising available services.Citation7 In addition to the physical and structural barriers, socio-cultural barriers such as lack of healthcare knowledge, shyness, and family and community attitudes, affect health-seeking behaviour and contribute to the low uptake of SRH services among adolescent girls in Nepal.Citation3,Citation8 As in many Asian countries, there are restrictive cultural norms that prevent open communication about sexual health.Citation9 Unmarried adolescents, in particular, face challenges, as premarital sex is taboo and this prevents uptake of essential SRH services.Citation3,Citation9

The Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Population has prioritised promoting adolescent SRH, as evident in policies and legal provisions such as the Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health Act 2018 and the Public Health Act 2018 that emphasise adolescent reproductive health rights. Nepal's national adolescent SRH programme integrates services such as counselling, education, and health promotion, obstetrics and family planning services, general health services, safe abortion services, school health education, and management of gender-based violence.Citation10 Adolescent-friendly services are provided at the primary level facilities, locally known as primary health care centres and health posts, and the secondary level facilities called district hospitals. The existing national community health workers (CHWs), known as Female Community Health Volunteers, also conduct community-based programmes for promoting adolescent SRH.Citation10

Gaps remain, however, in reaching sub-populations, including hard-to-reach rural young women, because adolescent-friendly health services are especially limited in remote areas.Citation10,Citation11 Many rural adolescents are also unaware of available health services due to a lack of demand generation interventions.Citation7,Citation10 As such, adolescent girls living in rural areas of the remote and hilly Far-Western Province of Nepal face notable disadvantages. In this region, gender inequality and violence against women remain major issues.Citation2,Citation12 Male migration for work from these areas is common and has also been associated with high rates of unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.Citation5,Citation13–15 Menstrual banishment, a traditional practice whereby women stay in small sheds outside the home during their monthly menses, while outlawed, continues to be practised in this region of Nepal.Citation16

A recent national report on the progress of national adolescent health activities noted that programmes need to better address equity, gender, human rights, and social determinants of health. It identified a clear need for gathering additional context-specific structural and socio-cultural data, as facilitators and barriers to utilising SRH services among adolescents vary across geography, socioeconomic status, and caste.Citation10 While there are a few studies exploring similar issues among adolescents in urban and semi-urban settings in Nepal,Citation17,Citation18 to our knowledge, there are no similar studies focused on the rural adolescent population. Furthermore, the literature is especially scarce on unmarried adolescent girls’ access to and utilisation of SRH services in Nepal because of the sensitive nature of these topics in this setting.

To attain the Sustainable Development Goals and achieve universal access to SRH, Nepal will have to expand access to neglected populations, including rural and unmarried adolescents. Sexual and reproductive rights, including access to quality SRH services, comprehensive sex education, gender equality, and the ability to make decisions about one’s own body, will need to be placed front and centre in this endeavour.Citation19 Therefore, it is essential to fill the evidence gaps of contextual barriers and facilitators by engaging young people in underserved areas to better tailor SRH services to their needs so that they are effective in the long term. In this study, we sought to identify structural and socio-cultural factors that impact utilisation of and access to SRH services for adolescent girls aged 15–19 living in Achham, a rural district of Nepal. We designed this study to inform the design of programmes to improve access to SRH information and comprehensive services for adolescent girls in this context and other similar settings.

Methods

Study site

This study was conducted in the Achham district situated in the Far-Western Province of Nepal, with an estimated population of 258,000.Citation12 Achham is one of Nepal’s poorest districts, and the challenging terrain creates physical barriers to access. The region is affected by the enduring consequences of a decade-long civil war, the highest HIV infection rate in the country, and longstanding poverty.Citation12,Citation14 The study was carried out by Nyaya Health Nepal (NHN) in collaboration with Possible, a US-based nonprofit that provided technical and financial support for the study. NHN is a Nepali non-governmental organisation, collaborating with the government and other partners to strengthen healthcare delivery in the Achham district. In collaboration with the Nepal Ministry of Health and Population and Possible, NHN implemented an integrated reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health intervention using trained, supervised, and salaried CHWs in several municipalities of Achham.Citation20,Citation21 CHWs are local women, who live in the communities they serve.Citation20 They are full-time paid employees, have a minimum tenth-grade education, and receive structured supervision for community-based care. CHWs’ functions include home-based counselling and health assessments of married, reproductive-aged women (15–49 years) using a mobile tool, making referrals, and supporting linkages to health facilities.Citation20,Citation21

Study design

This is a qualitative study designed to explore structural and socio-cultural factors that affect adolescent girls’ utilisation of and access to SRH services in Achham. We conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with CHWs and semi-structured individual interviews with married and unmarried adolescent girls aged 15–19 living in the Achham district. As local women, the CHWs provided important insights into the local context. The group discussions allowed us to explore generally accepted gender norms, social patterns, cultural practices, and areas of consensus and contestation. Given the sensitive nature of some of the topics discussed, we conducted individual interviews with the adolescent girls to allow participants to feel more comfortable and express their thoughts freely.

We used a purposive sampling technique to recruit participants of diverse characteristics based on age, caste, education level, marital status, and proximity to a health facility. CHWs identified potential participants of various backgrounds in their communities and referred individuals who were willing to participate to the research analyst (author A. Tiwari), who provided the study details and obtained verbal consent. We recruited CHWs from three different communities in Achham at their weekly team meetings for the FGDs. CHWs were from the same communities from which the adolescent girls were sampled. We chose these communities based on the variability of the number of years of implementation of the NHN CHW programme and geographical remoteness.

Between October 2018 to June 2019, the research analyst (author A. Tiwari), who is not a part of the NHN care delivery team, conducted the individual interviews and FGDs. The individual interviews lasted 30–60 minutes, and FGDs lasted about an hour. They took place in private spaces to ensure confidentiality. All interviews and FGDs were conducted in Nepali and audio-recorded with the participants’ permission.

The research analyst read a structured consent document to all participants and CHWs, and obtained verbal informed consent. For unmarried minors, we obtained verbal informed consent from a parent or legal guardian in addition to participant assent. As married girls younger than 18 years are considered emancipated and able to consent for themselves, we did not obtain verbal consent from their family members. Consent was not documented for any participants due to concerns about confidentiality breach as the study involved a vulnerable population and highly sensitive information.

Data analysis

The audio-recorded interviews and FGDs were transcribed and translated into English by a professional transcription service (Bhasa Nepal Pvt. Ltd.). Transcripts were uploaded into Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC 2016). Two researchers (authors A. Tiwari and W.W.) independently reviewed the data from the individual interviews and FGDs and developed codes using an inductive content analysis approach.Citation22 The initial coding represented codes relevant to the original research questions, as well as new concepts introduced by the data. The two researchers periodically reviewed the codes together and reconciled discrepancies. After coding eight individual interviews, we noted additional concepts of interest and incorporated them into the interview guides. Coding took place in conjunction with participant recruitment and data collection to ensure adequate data saturation. We added new codes as they emerged, and reconciled them after discussion.

In our initial analysis, we reviewed the data in the context of our original research questions. The themes that emerged from our open-coding included factors impacting SRH utilisation and access at multiple levels of the social system. Therefore, we chose to use the social ecological model (SEM) as the framework to organise and present our findings. The SEM emphasises the interplay between multiple levels of factors in shaping individuals’ health behaviours and experiences.Citation23 We re-organised the themes identified from the initial analysis into individual, interpersonal, community and social, and organisational and health system levels of the SEM framework.Citation23

Other themes around menstrual banishment also emerged from our data. We focused this manuscript on the factors affecting adolescent girls’ utilisation and access to SRH only. We will present other emerged themes in forthcoming manuscripts.

Ethics

The Nepal Health Research Council (approval # 461/2016) and Brigham and Women's Hospital (approval # 2017P000709) institutional review boards granted human subjects research approval for the study. The first author (WW) moved from Brigham and Women's Hospital to Boston Medical Center. At this point, only de-identified data was being used for analysis and manuscript preparation. WW was not engaged in the recruitment and study procedures as these activities were carried out by the research staff based in Nepal who were covered under the Brigham and Women's as well as the Nepal Health Research Council IRBs. As the study had ongoing approvals from the Nepal Health Research Council and Brigham and Women's institutional review boards, Boston Medical Center did not feel that the primary author's scope of work constituted research activities that the institution was engaged in and its institutional review board (H38196) exempted the study.

Results

We conducted 21 individual interviews with adolescent girls. Twenty-two adolescent girls were approached for interviews but one declined to participate. The ages of participants ranged from 15 to 19 years (median = 17). Two-thirds of the participants were unmarried. Two-thirds identified as being from an “upper” caste. The majority of study participants had an education level of Grade 5 and above, and a health facility within one hour of travel time from where they lived (). We conducted three FGDs with CHWs. Each FGD contained 6–8 CHWs, and all the CHWs approached for FGDs consented to participate. All the CHWs in this study completed tenth grade or higher. Less than 25% of CHWs were below 20 years of age, and less than 15% were of Dalit, Janjati, or other castes.

Table 1. Characteristics of adolescent participants

Adolescent girls and CHWs identified factors that influence adolescent SRH at the individual, interpersonal (peers, partners, and family), community and social, and organisational and health system levels ().

Figure 1. Factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and organisational levels that influence utilisation of and access to SRH services

Individual

Self-perceived lack of need and lack of knowledge of available SRH services

Participants expressed a self-perceived lack of need and knowledge of available SRH services. Some participants who were aware of family planning services felt that family planning was only necessary for older or married girls and that adolescent girls between the ages of 15–19 do not need family planning services: “ … we don't need to provide [family planning] for everyone … We need to get married over 20 years of age. Below 20 years, it is considered child marriage and we become weak” (15-year-old unmarried adolescent).

Low decision-making autonomy

Participants commented on women’s general lack of individual autonomy in making decisions about pregnancies: “Women here do not make decisions. There is a practice of early marriage in this place. Then they give birth to children right away. If they could make decisions, they wouldn't get pregnant” (18-year-old unmarried adolescent).

Shyness and shame

Participants described how adolescent girls internalised negative attitudes towards SRH and were ashamed of learning about reproductive health topics in general. As one participant expressed, “I used to feel shy [talking about contraceptives]. It was uncomfortable hearing about it the first time. I used to feel, ‘why would they talk about such disgusting things’” (18-year-old unmarried adolescent). CHWs also commented on the stigma associated with menstruation:

“[Adolescents] don't know how menstruation occurs. In this village, they think it is gross and [makes them] untouchable. They are unaware of family planning as well. They are not inclined to learn because they think that people will backbite (Nepali: “kura katne”) if they try to get information [about family planning] during adolescence.” (CHW-M)

Interpersonal (family/peers/partners)

Unsupportive family norms and lack of open communication

Participants shared how unsupportive family norms contributed to lack of open communication and non-disclosure around SRH issues and limited adolescent girls’ access to reproductive health information and services. As one CHW stated, “[It is difficult to go for services] because of confidentiality reasons and uncomfortable feeling of talking to elders in our family … It is hard because we cannot share anything with our mothers” (CHW-M). Therefore, adolescent girls sometimes turned to their peers for information: “Some friends who had their first periods before us, talk about it. It's not natural for our parents to talk to us about it, as we feel shy. Our mothers do not tell us, but our friends do” (18-year-old unmarried adolescent).

Need for permission from parents/partners/family members

Many participants noted the need for adolescent girls to obtain permission from parents, partners, and other family members to access SRH services; otherwise, they might face challenges, including inciting gossip, potential conflicts, and retribution:

“I cannot go [to a hospital] alone. I have to ask my parents first. People talk if [girls] go to a hospital alone. They may think that I am going there for an abortion … So, we have to ask our mothers before going there.” (16-year-old unmarried adolescent)

Community and social

Disparate gender norms

Participants identified several forms of gender discrimination in their communities that contribute to the lower status of women and girls in society. One was unequal education opportunities for girls because of the common perception that girls would inevitably be married off to their husbands’ families: “[Parents] say since their daughters will go to someone else's homes, it is not necessary to take care of them and educate them … daughters don’t need to study but should learn chores since they will ultimately go to someone else's homes” (18-year-old married adolescent).

Another form of discrimination included suppressing girls’ voices: “There is traditional thinking in society. For example, when a daughter answers in a meeting, they shut her up saying that she is a daughter, who will go away after marriage, and she should not answer back” (18-year-old unmarried adolescent).

Participants also described disparate gender norms in society around premarital sex: “[Girls] lie during adolescence because of the shame. As for boys, they know everything; they have no shame … They act haphazardly without shame” (16-year-old unmarried adolescent).

Son preference

Several participants also mentioned that preference for sons remains common in society. As one participant stated, “[Parents] think they should give birth to more sons as sons are preferred, so they keep giving birth until a boy is born. They feel that sons are their only support at the time of their death” (15-year-old unmarried adolescent).

Fear of judgment

In the context of these gender norms and expectations, participants reported feeling pressured to behave in a certain way. Participants felt that use of reproductive health services would go against established community norms and worried how community members would “talk” and gossip about girls who use reproductive health services. As one CHW put it,

“In this society, people have bad attitudes towards girls looking for such services. They blame girls for being indecent, so they do not openly go to receive these services. It is one of the barriers. There is a concept that girls shouldn't need family planning services before marriage … ”(CHW-B)

“If boys try to take advantage [of girls], girls worry about their families’ reputation. If their friends or relatives find out that they went to a health center, they will tell their parents and everyone else. They think that they will be humiliated.” (19-year-old married adolescent)

“If a girl becomes pregnant by mistake, first of all, she feels shame … Girls are afraid that people will know about it, that's why they don't go [to a health center]. Some girls buy abortion pills at the private clinic and may do a self-medicated abortion.” (17-year-old unmarried adolescent)

Some girls also travel to facilities farther away from their place of residence for abortion services to mitigate the stigma: “If they get pregnant by mistake, they want to go to a faraway health center. They worry that people will know about their unwanted pregnancy. If unmarried girls do such things, people in society shame them” (17-year-old married adolescent).

Organisational and health system

Gaps in sex education in schools

Most participants and CHWs noted the curriculum taught in schools is likely the primary source of SRH knowledge for most girls. While a few participants described a relatively comprehensive health class that taught topics including menstruation, family planning, puberty, and prevention of sexually transmitted infections, almost half reported having had minimal education on SRH issues or forgot what was taught in school. Another issue participants raised is that while SRH education is mandatory in Nepal, it does not help girls who do not receive a formal education or drop out of school before these topics are taught: “Also, many adolescent girls may not go to school. People like me may know about it because we are educated” (19-year-old married adolescent). Some participants were also reluctant to learn about SRH from male teachers: “It is easier with women, but it is harder to ask a question with the male teachers” (19-year-old married adolescent).

Lack of teachers

Participants explained that one of the barriers to adequate SRH education was the lack of teachers:

“In school, [menstruation] was in the Health subject, but we do not have class on that subject nowadays … The weakness of our school is the shortage of teachers … There are only two teachers at the high school level and they only teach their lessons and no other subjects.” (15-year-old unmarried adolescent)

Distance to a health facility and lack of female staff

Participants identified one of the barriers to reproductive health care access at healthcare facilities as the far travel distance to a facility. They also expressed feeling uncomfortable and shy accessing SRH services at the healthcare facility. Most were uncomfortable with the possibility of being cared for by male healthcare staff and felt less likely to speak freely with male staff:

“If I go to a hospital, I would feel uncomfortable talking about my problems if there is a male doctor. If there are auxiliary nurse midwives, nurses, and female staff, then I think I would be able to say anything that I wanted. I can ask anything about things like menstruation, the reasons for hair in the armpits, and how is it when you have sex while menstruating, et cetera.” (18-year-old unmarried adolescent)

Lack of supportive facility staff

Participants noted potential challenges accessing services due to unsupportive healthcare staff, particularly when it comes to abortion services for adolescent girls. One participant shared a situation when facility staff denied abortion services for unmarried girls in their community without family consent:

“They can get an abortion if they are married, but unmarried girls cannot do that. Some of them commit suicide. I have seen that in this village. Two girls died by hanging themselves. They got pregnant by mistake and went to [a hospital] to receive abortion services, but [hospital staff] denied services to them as they were unmarried. So, they committed suicide on the way … . [The hospital staff] said [the girls] should bring their husbands. Otherwise, they said they wouldn't abort.” (17-year-old married adolescent)

Recommendations to improve access to SRH information and services for adolescent girls

We asked adolescent girls and CHWs how they think adolescent girls’ access to SRH information and services could be improved. They provided recommendations at all levels of the SEM (Supplementary Table 1). Participants recommended girls speak up, overcome their shyness, and ask more questions about SRH. They recommended implementing programmes to increase knowledge and empower girls to be more vocal about their SRH. Many participants stressed the importance of educating family members on SRH issues, as many adolescent girls find it difficult to have open conversations with their families. Some participants recommended healthcare workers and volunteers help girls in their communities navigate seeking care. Many participants noted schools as a primary source of SRH information for girls and the need to improve the gaps in school-based education. To improve access to SRH services, some participants stressed the importance of having health centres closer to where people live and ensuring free services. Participants suggested ways to improve the quality of SRH services in facilities such as maintaining privacy and confidentiality, employing more female providers, providing more comprehensive SRH counselling, and displaying informative posters publicly.

Discussion

This study provides insights into structural and socio-cultural factors that negatively impact adolescent girls’ utilisation of and access to SRH services in a rural district of Nepal. The factors identified fall into multiple levels of the social system. We identified factors, often mutually influencing, that fall into each level of the SEM framework and may preclude adolescent girls from fully realising their SRH rights. These findings highlight the importance of a multi-level approach to improving adolescent SRH in this context.

On the individual level, participants identified a self-perceived lack of need for and knowledge of SRH information and services, shyness, and limited autonomy of adolescent girls as barriers to accessing reproductive health services. Their lack of individual decision-making autonomy is reinforced by the important role family members and partners play in this context for accessing reproductive health services. Potential consequences could arise, including threats of violence, if married adolescents did not obtain permission to use family planning services. Our findings are consistent with other studies in comparable settings looking at factors influencing utilisation of maternity services by adolescent girls.Citation17,Citation18,Citation24–26 Furthermore, family norms perpetuated silence around discussion of SRH topics in the home and adolescent girls lack safe spaces to access quality SRH information. While access to SRH information and services based on personal choices is core to SRH rights, the limited autonomy and agency of adolescent girls in this setting may make them vulnerable to violations of their SRH rights, including early marriage, reproductive coercion, and unplanned pregnancies.

Participants described traditional gender roles and social norms that continue to foster son preference, devalue girls, and promote gendered expectations in education and social behaviour. Our study shows girls have unequal educational opportunities and are expected to be quiet and obedient in public. Girls and boys also abide by different sexual mores. Our data are consistent with another study on adolescents in a peri-urban area of Nepal that found adolescent girls were more likely to be given the “bad behaviour” label when engaging in the same behaviours as their male counterparts.Citation8 Girls are afraid to access reproductive health services because it may be assumed they are engaging in premarital sex, which is highly stigmatised. Participants in our study spoke of how rumours or “backbiting” can ruin one’s reputation. Therefore, unmarried adolescent girls in this context are even less likely to access SRH services, and vulnerable to poor outcomes.

For especially sensitive issues, such as abortion care, adolescent girls prefer to travel farther away from where they live to maintain secrecy and avoid stigma. Family members and husbands seemed to be able to help mitigate stigma, as study participants noted better treatment for girls who access reproductive care with mothers or husbands. Some also purchase medications on their own as unregistered abortion medications are easily available over the counter in pharmacies or medical shops.Citation27 This may potentially contribute to more clandestine and unsafe abortions,Citation28,Citation29 even though abortion care is legal, free, and in theory, readily accessible in Nepal. Options for legal pharmacy distribution of registered abortion medications, promotion of self-managed abortions, or improved privacy and confidentiality at clinics may help to improve access to safe abortions for this population.

On the organisational and system levels, participants identified school and health facility factors that negatively impact SRH utilisation and access. Most study participants mentioned that they learned some aspects of reproductive health issues in the classroom, but identified gaps in their education. In Nepal, while students receive sex education starting in the 8th–9th grade (15–16 years old), it is not clear how comprehensive the materials are or whether it is uniformly implemented nationwide.Citation30 One study conducted in eight schools in Western Nepal found the quality of sex education to be poor and inconsistent due to inadequate support, training, and materials for teachers, teachers not wanting to discuss sensitive topics, and students also feeling similarly uncomfortable with learning about these topics.Citation30 Similarly, our study identified a lack of teachers in schools and students’ shyness, especially with male teachers, as limitations to school-based sex education. Implementation of a more uniform curriculum, better equipping and supporting teachers to facilitate discussions on sensitive topics, creating safe spaces for adolescents to discuss these issues, and preventing school dropout may help to improve the success of school-based sex education.Citation31

Adolescent girls raised issues of distance to healthcare facilities and quality of care issues mostly related to lack of female staff and healthcare worker attitudes, especially towards unmarried adolescents seeking care. Our findings are consistent with recent studies that identified persistent challenges of “adolescent-friendly” health facilities, including inadequate training of health workers to ensure quality services and a lack of health workers to provide gender-concordant services to meet the needs of adolescents.Citation7,Citation32

Although Nepal has committed to ensuring adolescent SRH rights by making quality SRH services and information available and accessible, our findings show this is not yet a reality for many adolescent sub-populations. In this context, family and community-level factors heavily impact individual adolescent girls’ decision-making autonomy and arguably outweigh individual-level factors. Therefore, interventions targeting family and community level factors are critical in this setting. Nepal's recent transition to a federal system and decentralisation also presents an important opportunity to implement interventions at system levels. The shift from bureaucratic decision-making at the central level to more decentralised decision-making at the local level facilitates prioritising local needs and increases health sector accountability at the local level.Citation33 Therefore, the findings from this study could help local governments to address organisational or health system barriers, including improving school-based sex education and tailoring recommendations for adolescent-friendly health services in the local context.

Stigma manifests at multiple levels of the social system. Adolescents expressed internal attitudes of “shame” and “shyness” when discussing or accessing SRH information and services. On the family level, there was lack of communication and non-disclosure. At the community level, gossip and judgment reinforced norms that made it challenging for adolescent girls to safely access SRH services. Any interventions in this setting must also address stigma as a cross-cutting theme and facilitate ways for adolescent girls to mitigate stigma.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. Due to logistical constraints and frequent migration of potential participants, we were only able to include participants who were available for interviews at times that coincided with the research analyst’s travel to that community. While these constraints posed some challenges in maximising heterogeneity in participants, we were able to recruit a diverse set of participants for the study and achieve an appropriate sample size. While we tried to include a diverse group of CHWs for the FGDs based on their experience with the CHW programme and geographic region, we collected minimal demographic data. In addition, for women and girls in this setting, the comfort and ability to respond to open-ended questions are often challenging despite measures to ensure privacy and confidentiality.Citation34 The voices of the most vulnerable girls may have been under-sampled.Citation35 Furthermore, due to resource limitations, we did not formally back-translate the interviews to assess for accuracy of the translations. Nuanced information might have been lost in the translation as Nepali local vernacular sometimes cannot be directly translated into English. One of the coders (A. Tiwari), however, is a native Nepali language speaker and frequently referenced the original Nepali transcripts, which may have mitigated this limitation to some extent. Lastly, there may have been an element of interviewer/researcher bias as the research analyst (A. Tiwari) who conducted the interviews, while not a member of the care delivery team, was employed by the non-profit organisation delivering care in the community during the study period. The research analyst is also from a different region of Nepal and of a different socioeconomic background than the participants. Study participants may have altered their responses based on this knowledge.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on multilevel factors that limit adolescent girls’ access to information on SRH, affect their utilisation of SRH services, and limit their ability to fully realise their SRH rights. Therefore, strategies that address factors along all the levels of the SEM framework are essential as there are interactions between levels as well as factors such as stigma affecting all levels. Adolescent girls’ individual agency and autonomy in this setting are extremely limited; therefore, interventions targeting the individual would likely be ineffective without concurrently addressing the interpersonal and community milieu factors that influence adolescent girls. Context matters for addressing barriers to SRH care, and must be considered when designing comprehensive SRH interventions for adolescent girls. Although our findings from a small area of rural Far-Western Nepal may not be directly transferable to other settings, our findings are largely consistent with similar adolescent SRH studies in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The socio-cultural barriers that this study identified, including the role of stigma, are likely relevant for adolescent SRH even in non-rural settings in Nepal and other countries.

Supplementary Table 1: Illustrative quotes on recommendations from the participants on improving adolescent girls’ access to SRH information and services.

Download MS Word (22.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to express our appreciation to the Nepal Ministry of Health and Population for their continued efforts to improve the public sector healthcare system in rural Nepal. We are also indebted to community health workers, nurses, and programme associates, whose commitment to serving our patients and dedication to improving the quality of health care in rural Nepal continues to inspire us.

Author Contributions

Aparna Tiwari and Wan-Ju Wu are co-first authors. WW conceived the study and serves as guarantor for the work. The study grew out of discussions between WW, SM, A. Thapa, DC, and AG. WW, A. Tiwari, DC, RK, SH, S. Sapkota, and SM contributed to developing and refining the study tools. AB, A. Thapa, BB, HJR, SK, S. Saud, and YK supported the participant recruitment strategy and coordination of study interviews and focus group discussions. A. Tiwari conducted the qualitative data collection. A. Tiwari and WW coded and analyzed the data with support from DC and SM. A. Tiwari, WW, and SM drafted the manuscript. AG and RV reviewed and provided expert feedback for the manuscript. All authors reviewed, provided feedback, and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chandra-Mouli V, Ferguson BJ, Plesons M, et al. The political, research, programmatic, and social responses to adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights in the 25 years since the international conference on population and development. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(6):S16–S40.

- Preiss D. Banished to a ‘menstrual shed,’ a teen in Nepal is bitten by a snake and dies; 2017.

- UNFPA, UNESCO, WHO. Sexual and reproductive health of young people in Asia and the Pacific: a review of issues, policies, and programmes. Bangkok; 2015.

- Ministry of Health (MOH)/Nepal, New ERA/Nepal, ICF. (2016). Nepal demographic and health survey. Kathmandu, Nepal. MOH/Nepal, New ERA, and ICF; 2017.

- Aguilar AM, Cortez R. Family planning: The Hidden need of married adolescents in Nepal. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2015.

- Kafle RB, Paudel R, Gartoulla P, et al. Youth health in Nepal: levels, trends, and determinants. Rockville (MD): ICF; 2019.

- UNFPA, UNICEF, MoHP. The qualitative study on assessing supply side constraints affecting the quality of adolescent friendly health services and the barriers for service utilization in Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal; 2015.

- Pandey PL, Seale H, Razee H. Exploring the factors impacting on access and acceptance of sexual and reproductive health services provided by adolescent-friendly health services in Nepal. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0220855.

- Adhikari R, Tamang J. Premarital sexual behavior among male college students of Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):241.

- WHO. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health programme to address equity, social determinants, gender and human rights in Nepal: report of the pilot project. New Delhi: World Health Organization. Country Office for Nepal; 2017.

- Regmi PR, van Teijlingen E, Simkhada P, et al. Barriers to sexual health services for young people in Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28(6):619–627.

- UNFCO. District Profile: Achham. UN Resident Coordinator and Humanitarian Coordinator Office; 2013.

- Poudel KC, Jimba M, Okumura J, et al. Migrants’ risky sexual behaviours in India and at home in far western Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(8):897–903.

- Vaidya NK, Wu J. HIV epidemic in Far-Western Nepal: effect of seasonal labor migration to India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):310.

- Johnson DC, Lhaki P, Bhatta MP, et al. Spousal migration and human papillomavirus infection among women in rural western Nepal. Int Health. 2016;8(4):261–268.

- Thapa S, Bhattarai S, Aro AR. ‘Menstrual blood is bad and should be cleaned’: a qualitative case study on traditional menstrual practices and contextual factors in the rural communities of far-western Nepal. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119850400.

- Shahabuddin ASM, Delvaux T, Nöstlinger C, et al. Maternal health care-seeking behaviour of married adolescent girls: a prospective qualitative study in Banke District, Nepal. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(6):e0217968.

- Maharjan B, Rishal P, Svanemyr J. Factors influencing the use of reproductive health care services among married adolescent girls in dang district, Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):152.

- Galati AJ. Onward to 2030: sexual and reproductive health and rights in the context of the sustainable development goals. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2015;4:18.

- Maru S, Nirola I, Thapa A, et al. An integrated community health worker intervention in rural Nepal: a type 2 hybrid effectiveness-implementation study protocol. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):53.

- Citrin D, Thapa P, Nirola I, et al. Developing and deploying a community healthcare worker-driven, digitally-enabled integrated care system for municipalities in rural Nepal. Healthcare. 2018;6(3):197–204.

- Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246.

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377.

- Choulagai B, Onta S, Subedi N, et al. Barriers to using skilled birth attendants’ services in mid- and far-western Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13(1):49.

- Abajobir AA, Seme A. Reproductive health knowledge and services utilization among rural adolescents in east Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):138.

- Shahabuddin ASM, Nöstlinger C, Delvaux T, et al. What influences adolescent girls’ decision-making regarding contraceptive methods use and childbearing? A qualitative exploratory study in Rangpur District, Bangladesh. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0157664.

- Puri MC. Providing medical abortion services through pharmacies: evidence from Nepal. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;63:67–73.

- Wu W-J, Maru S, Regmi K, et al. Abortion care in Nepal, 15 years after legalization: gaps in access, equity, and quality. Health HumRights. 2017;19(1):221–230.

- CREHPA Guttmacher Institute. Abortion and unintended pregnancy in Nepal [fact sheet]. CREHPA Guttmacher Institute; 2017.

- Pokharel S, Kulczycki A, Shakya S. School-based sex education in Western Nepal: uncomfortable for both teachers and students. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(28):156–161.

- Mattebo M, Bogren M, Brunner N, et al. Perspectives on adolescent girls’ health-seeking behaviour in relation to sexual and reproductive health in Nepal. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2019;20:7–12.

- Napit K, Shrestha KB, Magar SA, et al. Factors associated with utilization of adolescent-friendly services in Bhaktapur district, Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2020;39(1):2.

- Thapa R, Bam K, Tiwari P, et al. Implementing federalism in the health system of Nepal: opportunities and challenges. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(4):195–198.

- Wu W-J, Tiwari A, Choudhury N, et al. Community-based postpartum contraceptive counselling in rural Nepal: a mixed-methods evaluation. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(2):1765646.

- Ellard-Gray A, Jeffrey NK, Choubak M, et al. Finding the hidden participant: solutions for recruiting hidden, hard-to-reach, and vulnerable populations. Int J Qual Methods. 2015;14(5):1609406915621420.