Abstract

Since the 1990s, the global approach to family planning has undergone fundamental transformations from population control to addressing reproductive health and rights. The Indian family planning programme has also transitioned from being vertical, target-oriented, and clinic-based to a supposedly target-free, choice-based programme that champions reproductive rights. Despite contraceptive choices being offered and voluntary adoption encouraged, there is a heavy reliance on female sterilisation. Community health workers, known as ASHAs, are responsible for on-ground implementation of family planning policies and are incentivised to promote sterilisation as well as other methods. This study explored perspectives to understand of the role of female sterilisation in Indian family planning and whether policy is reflected in implementation. Secondary ethnographic data from Rajasthan, which included twenty interviews and five group discussions, were used to understand the perspectives of ASHAs. Primary data included five key informant interviews to understand the perspectives of experts nationally. Data were analysed thematically with a combination of deductive and inductive coding. Themes that emerged included choice, population control and coercion, family planning targets, quality and experience of services, historical factors and social norms. Despite the official policy shift, there appears to be narrow implementation which is still target-driven, relies heavily on female sterilisation, while negotiating between achieving population stabilisation and upholding reproductive rights. There is a need to emphasise spacing methods, ensure a rights- and choice-based approach and encourage male participation in reproductive health decisions.

Résumé

Depuis les années 90, la conception internationale de la planification familiale s’est profondément transformée, passant d’un contrôle démographique à une réponse à la santé et aux droits reproductifs. Le programme indien de planification familiale a lui aussi fait la transition d’activités verticales, axées sur les objectifs et basées dans les établissements de santé à des interventions fondées sur la liberté de choix, supposément affranchies d’objectifs et qui protègent les droits reproductifs. Même si des choix contraceptifs sont proposés et que l’adoption volontaire est encouragée, le programme fait encore une grande part à la stérilisation féminine. Les agents de santé communautaires, connus sous le nom d’ASHA, sont responsables de la mise en œuvre sur le terrain des politiques de planification familiale et sont encouragés à promouvoir la stérilisation ainsi que d’autres méthodes. Cette étude a exploré différentes optiques pour comprendre le rôle de la stérilisation féminine dans la planification familiale indienne et s’est demandé si la politique était traduite dans la mise en œuvre. Des données ethniques secondaires provenant du Rajasthan, qui comprenaient 20 entretiens et cinq discussions de groupe, ont été utilisées pour comprendre les perspectives des ASHA. Les données primaires incluaient cinq entretiens avec des informateurs clés pour cerner le point de vue des experts au niveau national. Les données ont été analysées thématiquement avec une association de codage déductif et inductif. Les thèmes qui sont apparus comprenaient le choix, le contrôle démographique et la coercition, les objectifs de la planification familiale, la qualité et l’expérience des services, les facteurs historiques et les normes sociales. En dépit du changement politique officiel, il semble y avoir une mise en œuvre étroite, encore subordonnée aux objectifs, qui fait une grande place à la stérilisation féminine, tout en négociant entre une stabilisation de la population et le respect des droits reproductifs. Il est nécessaire de souligner les méthodes d’espacement des naissances, de garantir une approche fondée sur les choix et les droits, et d’encourager la participation des hommes aux décisions de santé reproductive.

Resumen

Desde la década de 1990, el enfoque mundial de planificación familiar ha pasado por transformaciones fundamentales, desde el control de la población hasta el abordaje de la salud y los derechos reproductivos. El programa de planificación familiar de India también ha hecho la transición de ser vertical, orientado a objetivos y basado en centros de salud, a ser un programa supuestamente libre de objetivos y basado en opciones, que defiende los derechos reproductivos. A pesar de que se ofrecen opciones de métodos anticonceptivos y se fomenta la adopción voluntaria, hay una enorme dependencia de la esterilización femenina. Agentes de salud comunitaria, conocidas como ASHA, son responsables de aplicar en el terreno las políticas de planificación familiar, y reciben incentivos para promover la esterilización y otros métodos. Este estudio exploró perspectivas para entender el papel de la esterilización femenina en la planificación familiar india y si la política se refleja en la implementación. Se utilizaron datos etnográficos secundarios de Rajasthan, que incluyeron veinte entrevistas y cinco discusiones en grupos focales, para entender las perspectivas de las ASHA. Los datos primarios incluyeron cinco entrevistas con informantes clave para entender las perspectivas de expertos a nivel nacional. Se analizaron los datos temáticamente con una combinación de codificación deductiva e inductiva. Los temas emergentes fueron: elección, control de la población y coacción, objetivos de planificación familiar, calidad y experiencia de los servicios, factores históricos y normas sociales. A pesar del cambio de política oficial, parece haber una implementación limitada que continúa impulsada por objetivos y depende en gran medida de la esterilización femenina, a la vez que negocia entre lograr estabilización poblacional y defender los derechos reproductivos. Es necesario hacer hincapié en los métodos de espaciamiento, garantizar un enfoque basado en derechos y opciones y motivar la participación de los hombres en las decisiones sobre la salud reproductiva.

Introduction

Since the 1950s, the approach to family planning internationally has been guided by the need to control population growth, particularly in developing countries with high fertility. Achieving demographic goals by curbing growth and lowering fertility could promote economic development and keep a check on scarce resources.Citation1 The International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo (ICPD 1994) marked a fundamental policy shift in family planning from population control to reproductive health and rights. By framing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and therefore family planning in terms of human rights, this was a move away from population control to viewing reproductive health and rights of individual women and men more holistically.Citation2 The Programme of Action recognised the right of “all people to have access to comprehensive reproductive health care, including voluntary family planning/contraception and safe pregnancy and childbirth services.”Citation3 These developments resulted in several advances in policies and programmes across the world.

The global development agenda in the decades since has reaffirmed a commitment to SRH - from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs 2000–2015) to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 2015–2030). SDG Targets across Goals 3 (health) and 5 (gender equality and empowering women) address ensuring universal access to SRH, which includes family planning.Citation4 This discourse acknowledges the importance of the “availability, accessibility and non-discrimination” principles enshrined in reproductive rights, which the SRH community has striven to achieve since 1994.Citation5 Universal Health Coverage (UHC), central to Goal 3, and SRH are inextricably linked. Policy experts believe that in order to achieve both, a comprehensive approach that ensures equity in access, quality of care and accountability in implementation will be crucial.Citation4

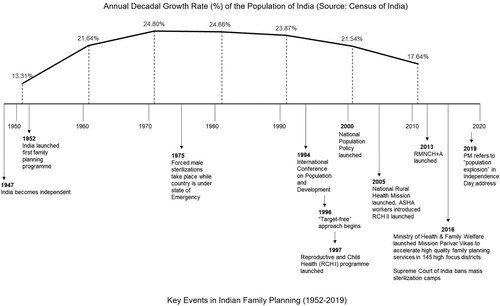

Among the first developing countries to launch a national family planning programme in 1952, India too was initially driven by population control and a fear of challenges to economic development.Citation6,Citation7 Since being launched, the programme has been accredited with contributing to a declining population growth rate () and total fertility rates (TFRs).Citation8 Following ICPD Cairo (1994), the policy and programme have undergone dramatic transformations. From a vertically-run, target-driven, incentive-based, sterilisation-focused programme, it was reoriented to address broader family and health concerns through a decentralised, target-free, client-focused approach.Citation9 The Indian government made a commitment “towards voluntary and informed choice and consent of citizens while availing of reproductive health care services, and continuation of the target-free approach in administering family planning services” in its National Population Policy (2000).Citation10 Key strategies of the current RMNCH + A (Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and Adolescents, 2013) programme include increased focus on birth spacing services, encouraging male participation, and a rights-based approach.Citation11 In 145 high focus districts with the highest TFRs in the country, Mission Parivar Vikas (Mission Family Welfare, 2016) adopts a multi-pronged approach to “accelerate access to high quality family planning choices”, while incentivising beneficiaries and health workers.Citation12

Local community health workers (CHWs) and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) have been key to the on-ground operationalisation of the programme.Citation13 Since 2005, ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists), an all-female cadre of CHWs who are first-contact healthcare workers and part of the National Rural Health Mission, have taken on family planning among their many responsibilities.Citation14 They are volunteers who are not paid a salary but receive performance-based incentives for certain services.Citation15 ASHAs provide many services for reproductive and child health such as counselling women on contraception, birth preparedness, breast-feeding, providing access to oral pills and condoms.Citation11

Despite the official move away from demographic goals in the family planning policy, there remain those who believe there is a population problem that needs controlling. In July 2019, a Population Regulation Bill was introduced as a Private Member’s bill in the upper house of the Indian Parliament, calling for punitive action against people with more than two living children, intending “to create a balance between people and the resources, human resources as well as natural resources”.Citation16 In August 2019, on India’s 73rd Independence Day, Prime Minister (PM) Modi highlighted the issue of a “population explosion” and the need for discussion and awareness on the matter.Citation17 He congratulated those with small families for contributing to the nation’s development and demonstrating patriotism. In December 2020, an advocate filed a petition in the Supreme Court to introduce a population control law. The Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MoHFW) however responded with an affidavit affirming the voluntary nature of India’s Family Welfare Programme where reproductive decision-making lies with the people themselves.Citation18

Female sterilisation in India

Six modern contraceptive methods are offered by the Indian family planning programme to delay, space, and limit births.Citation6 Despite increased use of spacing methods like pills and condoms, female sterilisation dominates the method-mix in India and accounts for over two-thirds (67.07%) of modern contraceptives used among Indian women (15–49 years); Rajasthan also presents similar trends at 68.27% ().Citation19,Citation20 Female sterilisations occur at younger ages in India – in 2016, the median age was 25.7 years – with regional variations in its uptake.Citation21,Citation22 Compensation or incentive schemes for sterilisation acceptors, service providers, and community health workers are provided by the MoHFW.Citation6

Table 1. India & Rajasthan – key family planning facts at a glance

This reliance on female sterilisation is neither unique to nor new in India. Globally, female sterilisation is the most commonly used method and constitutes 50% or more of contraceptive use in four countries, including India.Citation24 Sterilisations have been the most common method of family planning in India since Independence.Citation22 Although coercive, state-sponsored male sterilisations in the 1970s led to a decline in these figures, use of female sterilisation has steadily increased since.Citation7,Citation19 Bangladesh and Sri Lanka also had focused their programme on female sterilisations. The two countries shifted emphasis towards reversible contraceptive methods in the late 1980s and as a result, the proportion of female sterilisations has declined.Citation25,Citation26

There is no recognised “ideal” contraceptive method-mix since family planning needs evolve with changing fertility, age structures, and childbearing preferences.Citation24 Despite a recent focus on increasing spacing methods, there is a disproportionately high use of this “most popular” limiting method which could indicate issues of access to service delivery and unmet needs of delaying pregnancy or spacing births in India.Citation6,Citation27 The current global development agenda calls for ensuring universal access to SRH, which the Indian policy discourse echoes, using a rights-based approach and encouraging voluntary adoption of family planning.Citation4 Men and women are therefore meant to be free to choose the method they want. This dependence on female sterilisation as a contraceptive method raises questions on whether these high numbers reflect societal and individual preferences or limited access to a range of methods.

Studies on female sterilisation in India have focused on barriers and facilitators for acceptors, quality of services, post-sterilisation regret, clinical studies, and experiences of women and men.Citation22,Citation28–30 While the predominance of female sterilisation in Indian family planning policy and programmes has been addressed, there is a lack of studies bringing together perspectives from policy and practice levels. It is valuable to explore how national policies are interpreted and manifest themselves on the ground. This study explored the role that female sterilisation plays in Indian family planning and whether policy is reflected in implementation, through the perspectives of national-level policymakers and ASHAs.

Methods

We used a qualitative research design which is best suited to explore perspectives to understand the role of female sterilisation in Indian family planning policy and programmes. Secondary and primary qualitative data were supplemented with a policy document review ().

Table 2. Data collection overview

Secondary data: ethnographic data on ASHAs in Rajasthan

To build upon perspectives of CHWs on female sterilisation and family planning, secondary in-depth interviews and group discussions with ASHAs were used. These secondary qualitative data were originally collected in 2017–18 as part of “The Role of ASHAs in the Private Sector: an Ethnographic Study on Maternal Health in Rajasthan” by the second and last author.Footnote* The aim of the ethnographic study was to explore the daily experiences of ASHAs working in Rajasthan, particularly their interaction with public and private health systems. Although the focus of the ethnographic study was on a different topic, how ASHAs felt about female sterilisation emerged as a key issue in the coding and data analysis. work.Footnote† We draw on in-depth interviews and focus group discussions from this study.

The ethnographic study was conducted in a district of Rajasthan, where it was connected with an evaluation of a programme in that state.Footnote‡ Approaches included observation, in-depth interviews, group discussions, and a number of participatory methods. Consent was obtained from the study respondents and a copy of their signed consent form and an information sheet were shared with respondents. Participants consented to the use of data in any resulting publications. While we refer to the secondary analysis of qualitative data the study was in line with the aims of the original study and did not require renewed consent from participants.

The first author familiarised themselves with the selected transcripts of secondary data (n = 25) before coding. Transcripts were then coded with a combination of deductive and inductive coding using QSR International’s NVivo 12 (Codebook available in Appendix 1A). They were analysed thematically to understand the perspectives and opinions of ASHA workers regarding female sterilisation in family planning.Citation31 During analysis, the first author had conversations with the second and last authors and remained mindful of the limitations that accompany secondary data analysis. In particular, since the study focussed on maternal health, the data was generated within that study context.

Primary data: key informant interviews

Subsequently, five semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted in India by the first author in August and September 2019 to capture national policy perspectives. While the original aim was to interview national-level policymakers, the sample inclusion criteria were expanded to include academics, civil society actors, and other experts in the field. This was done because of challenges in policymakers agreeing to be interviewed. Since the research enquiry is very specific, there are few known experts in this field in India. Therefore, sampling strategy included a mix of purposive and snowball sampling.

Interviews were scheduled with participants keeping in mind their preference of date, time, and location. They were given the chance to ask questions regarding the research prior to and during the interview. Before beginning the interview, the researcher went through the consent procedure with the participants and explained their right to withdraw consent at any point they wished. They were also assured that recording interviews was optional and that if they chose, recording would be stopped at any point.

Three interviews were conducted face-to-face and two interviews were conducted telephonically. Interview duration ranged between 35 minutes and 1 hour 10 minutes. A topic guide had been developed and piloted before use (Appendix 2). The semi-structured format of the interview provided flexibility to obtain open-ended answers as well as probe further where newer themes emerged. Field notes were also maintained to capture issues and trends that emerged from each interview.

These interviews were conducted primarily in English with occasional portions in Hindi; the researcher conducting these interviews is fluent in both languages. These were transcribed verbatim and prepared for analysis. Since the area of inquiry is specific, with few key informants working in this area, de-identification was not possible. Data familiarisation began as the data was being generated and transcribed. We undertook a thematic approach for analysis with a combination of deductive and inductive coding using QSR International’s NVivo 12.Citation31 (Codebook available in Appendix 1B).

Ethical considerations

The ethnographic data collected in Rajasthan received ethical clearance from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Observational/Interventions Research Ethics Committee (Reference No. 9083, dated 9 June 2016) and local ethical clearance in India from Sangath Institutional Review Board (Reference No. LPK_2017_025, dated 9 February 2017). The interviews and transcripts were anonymised before they were shared with the first author.

The primary data collected in this study were considered low-risk as the participants were not deemed to be vulnerable. Primary data collection was given ethical clearance by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine MSc Research Ethics Committee (Reference No. 16936, dated 7 May 2019) and local ethical approval in India by Sangath Institutional Review Board in India (Reference No. LPK_2017_025, dated 7 August 2019).

Policy document review

Publicly available policy documents of the Indian Government on family planning and ASHAs (Appendix 3) were accessed electronically via the MoHFW and other relevant websites including that of the ICPD Conference. They were reviewed, coded into themes manually, and synthesised thematically. The scope of documents reviewed was limited to those produced after India’s official shift to a target-free approach in 1996, up to 2020, given the paradigm shift in policy and programmes in the 1990s. During the period of fieldwork, a high-profile speech was made by the Prime Minister that raised the issue of family planning and this was also included; the transcript of the speech was reported in national newspapers.

Findings

Study findings from secondary and primary qualitative data are presented below. Themes that emerged include choice in family planning, men and contraception, population control and coercion, family planning targets, quality and experience of services, historical factors and social norms. Qualitative insights are supplemented with information from relevant policy document reviews.

“There will be choice when there are options”: family planning and choices

Since the mid-1990s, the family planning programme promoted a client-focused approach and expanded contraceptive options.Citation11 The National Population Policy (NPP) too outlined its commitment to providing increased contraceptive choices, making accessible a “wide basket of choices” as well as information and counselling services.Citation10 India’s commitment at FP2020 includes efforts to expand the range of contraceptive options available.Citation32 The RMNCH + A strategy (2013) emphasised spacing and limiting methods equally and sought to promote “children by choice” as a key approach. Sterilisation services of course remain a priority intervention.Citation33

Female sterilisation “remains the most popular modern contraceptive method”.Citation27 On whether this reflects voluntary demand, one key informant referred to their experience with southern Indian states. They explained that over a couple of generations, a level of social acceptance for sterilisation was built as a result of health workers achieving targets under tremendous pressure in the 1980s in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Newer generations preferred to opt for it as it worked for their mothers’ generation.

“You get married, you immediately have a child, you have a second child as soon as you can and then you have sterilisation. That’s the kind of socially accepted” … (Academic researcher)

Other key informants believed women were not actually offered options to begin with, so that female sterilisation became the default choice. They felt that while people wanted smaller families, there is a lack of options discussed or offered. Further, they were of the view that there was no understanding of who needed which methods, no counselling before marriage or appropriate education for adolescents, in contrast to a supposedly client-focused approach.

“But the only thing they’ve seen is sterilisation. I’ve had people sitting here saying women’s choice is sterilisation. This is nonsense. There will be choice when there are options.” (Head, civil society organization)

“No attempt to understand the decisions they (women) are making and why they are making the decisions they are making and going along with … The approach is wrong.” (Academic researcher)

ASHAs interviewed reported that they counselled and offered all available choices to couples such as condoms, pills and IUDs for spacing or delaying first births. However, when it came to female sterilisations or “operations”, it appeared they took extra efforts to “motivate” and follow-up with women. While describing the cyclical process of checking on all beneficiaries in their areas during a group discussion, ASHAs mentioned visiting certain homes periodically in case there was a woman who wanted to undergo the operation. They also reported picking houses to visit based on whether they knew of a “potential operation client” there. Some ASHAs shared motivation tactics they employed to convince women to undergo sterilisation. Helping people understand they wouldn’t have to spend any money as well as guaranteeing no adverse outcomes were mentioned. While it didn’t come up frequently, one ASHA specifically described a tactic that was sensitive to people’s preference for giving birth to sons. She used herself as an example of someone who had undergone sterilisation while having no sons. However, she admitted that she lied about having undergone the operation but felt that unless she used herself as an example, it would be hard to convince others. By emphasising that she only had two daughters, people were more likely to be brought on board. Some ASHAs alluded to certain socio-cultural barriers in motivating women. For instance, those belonging to a particular tribe in the area viewed children as gifts of god and consequently did not like using either spacing or limiting contraceptive methods.

“Till the time operation is not done … we have to go to motivate her.” (ASHA)

“Government knows it that due to ASHAs how much progress has been made. How many operations for sterilisation are being done and earlier were not done, that Government knows.” (ASHA)

“Male sterilisation was never popular except when it was a coercive programme”: men and contraception

Between 1975 and 1977, India was under a State of Emergency, during which time civil liberties were curbed and the PM ruled by decree. The programme took the form of coercive, state-sponsored male sterilisations.Citation34 Estimates of Indian men who were forcefully sterilised in the span of a year vary between 6 and 8 million.Citation34,Citation35 The backlash since has led to steep declines in male sterilisation.

When key informants were asked for views on other contraceptive choices in India, participants primarily discussed male sterilisations. Nationally, male sterilisation figures lie low at 0.3%.Citation28 All key informants agreed that low figures were largely attributable to the history of state-sponsored coercive sterilisations in the 1970s. They also agreed that vasectomies, especially non-scalpel vasectomies (NSVs), were far simpler procedures when compared to female sterilisations. Lack of trained human resources to perform NSVs was identified as a key challenge.

“Then in the 2000s, they started doing male again in the name of promoting male vasectomy. That’s when NSV came … You couldn’t find anyone to do an NSV. No one was trained.” (Head, civil society organisation)

According to India’s Vision FP2020, districts have been encouraged to increase provision of NSV services with hopes to trigger supply-induced demand.Citation32 The RMNCH + A strategy recognises the need to promote NSVs to increase male participation in family planning.Citation33 A policy imperative in the National Health Policy (2017) is to increase “the proportion of male sterilisation from less than 5% currently, to at least 30% and if possible, much higher”.Citation36 However, as one key informant pointed out, there have been no strategies or roadmaps outlined to achieve this. Another key informant believed that there was a lobby for some reason against RISUG (Reversible Inhibition of Sperm Under Guidance), a non-hormonal male contraceptive, and the focus continued to be on female sterilisation.

“Given the context that India is patriarchal society and there may still opposition to vasectomy which means we may have to put in much more effort to get this 30% done.” (Academic researcher)

Most key informants felt patriarchal norms in Indian society made it hard to convince men to undergo sterilisation because of associated notions of loss of manhood and masculinity. They felt that men as well as women feared this “loss” through male sterilisation. Aside from this, one key informant suggested that in cases where a man had undergone sterilisation and his wife conceived due to sterilisation failure, she could be blamed incorrectly for having an extramarital affair. In their experience, women opted to get sterilised instead of their husbands for such reasons.

“You people want to have children, we want to make sure you don’t”: perspectives on population control and coercion

In the post-ICPD Cairo era, the family planning approach addresses reproductive health more broadly, with an emphasis on voluntary adoption.Citation9 In addition, however, the NPP promotes a small family norm, without explicitly referring to a two-child limit.Citation10 All key informants were of the view that on-the-ground programmes continued to be geared towards controlling the population, and people’s reproductive decision-making as well as women’s bodies. These interviews were conducted in late August 2019 and therefore captured responses to the PM’s Independence Day address where he spoke of a “population explosion”.Citation17 Major policy initiatives (like the Clean India MissionCitation37) have been announced on occasions of such import in the past. All key informants shared their apprehensions about the speech indicating a change in policies with perhaps a re-introduction of the two-child policy. There was concern over the use of the term “population explosion” since data suggests the population growth rate has slowed down considerably. They further perceived this to be coercive, against reproductive rights, and unnecessary. Some key informants were concerned that the speech was targeted towards religious minorities, such as Muslims, and argued that the numbers suggested that fertility was coming down across the board.

Key informants felt that the emphasis on adoption of female sterilisation after having two children revealed attempts at population control. While TFRs as well as desired fertility rates across the nation reflected the voluntary existence of a two-child norm, key informants felt the government was trying to push people into having two children in quick succession and then to having them sterilised. They felt the government was trying to control reproductive decision-making as well as women’s bodies. Further, female sterilisation was seen as a mechanism to put the onus of decision-making only on women instead of the couple.

“We have always taken the comfortable route of controlling women. We have not actually taken the route of making sure that the men are also involved in this and men are also made to be accountable. We have actually burdened the women with it.” (Academic researcher)

Interviews with ASHAs revealed an emphasis on bringing specific cases which are considered “good”, in line with what was suggested by most key informants. Good cases here are couples who opted for sterilisation after two children only. On the other hand, one ASHA stated that she felt it would be better to have those with more than two children undergo sterilisation instead; after all, what if something happens to those with only two children? Another ASHA recalled a doctor scolding a woman pregnant with her eighth child for not having undergone sterilisation. However, there was a contrasting instance where a woman with four children was sent home with tablets instead of being sterilised.

“We bring case after four or five children that is not considered, those who get done after two that is big case. That is good case.” (ASHA)

“Only one target can be achieved”: chasing targets

The Indian government abolished family planning targets in 1996.Citation7 Targets were initially replaced by the Community Needs Assessment Approach (CNAA) which involved CHWs assessing needs and preferences by consulting local communities to calculate requirements, which were taken as targets.Citation38 CNAA was eventually abandoned and replaced by Expected Levels of Achievement (ELA) due to decreasing performance/achievement of the programme and discrepancies between district and national data and targets. ELAs are calculated using a mathematical model that takes into account birth rate according to birth order and unmet need and uses District Level Health Survey and Sample Registration Survey data.Citation38

Key informants uniformly disagreed with the notion that the ELA approach was indeed target-free. They perceived a target-free approach to be purely rhetorical, only on paper, while targets had just taken on a new name, i.e. ELAs.

“Targets have never gone really. And you know it is deeply entrenched in the mind of the system. All the way up to down. That family planning can’t happen without targets. So they’ve changed the name and they call this or that.” (Former head, research organisation)

“But on the other side, the imposition of a contraceptive specific target, although it has been abolished since the 1990s. It was re-imposed in the name of expected level of achievement. ELA. Which … and there is too much of a pressure on that and that has created, that has been creating problems.” (Former policymaker)

ASHAs receive incentives for performing certain activities including encouraging institutional deliveries, immunisation, undertaking health surveys, and helping individuals get a tubectomy or vasectomy; incentives for the latter tend to be higher than the rest.Citation15 When ASHAs spoke of female sterilisation, it was most commonly in relation to targets or, as they’re officially referred to, ELAs. While it is tempting to relate chasing targets to performance-based incentives, the following quote frames female sterilisation within targets very well:

“Only one target can be achieved, either LS (laparoscopic sterilisation) will be achieved that target will go forward, family planning, or will increase ANC (ante natal care). Only one will happen. (Officials) says increase ANC also and get LS also done. Do everything hundred percent. How can we do everything hundred percent? The LS is going on well, I have achieved that target but ANC are less in number in my area. Half of the people, madam, get the PPIUD inserted after delivery. Half are aware, for instance they use some family planning methods, some keep three years gap between two children, like this entire target has been made in XXX. Then from where should I bring ANC?” (ASHA)

Respondent: They respect me. On one call they come for vaccination etc.

Interviewer: But then why is there difficulty?

Respondent: Difficulty is this that the cases of sterilisation etc they give to the people of their own caste. (ASHA)

What also emerged from the ethnographic work was an unspoken competition with other health workers in relation to performance-based incentives and targets, including sterilisation. ASHAs complained that no matter who motivated the case to undergo sterilisation, it came down to who was present at the health facility during the procedure in order to have their name written on the case file to get incentives. In interviews, ASHAs reported that doctors doing the procedure had the authority to put names on the case file. While experiences are mixed, some instances suggested a tenuous relationship and power dynamics between doctors and ASHAs. During a case of post-partum sterilisation procedure, an ASHA reported that a doctor refused to believe that she had motivated the woman and instead put the case down to “self-motivation” since the ASHA wasn’t present during the delivery of the child. Another ASHA reported that once it took three visits to convince a woman to get the operation. When the woman finally went to get the operation, the doctor put his own name on the case. This ASHA didn’t feel she could complain as the doctor is higher up in the hierarchy. Another ASHA reported that a patient once questioned the doctor in the private sector for charging her for the operation. The doctor subsequently got irritated and took the case away from the ASHA. While the patient no longer paid, the ASHA received no benefit. In most narratives involving doctors, ASHAs are of the opinion that doctors actively don’t want ASHAs to get a case in their name.

“We motivate them so much. For one case, four five times we go and visit and prepare the case. We take the case and go and then if the case doesn’t come in our name means? What is the point in finding [case]? … I feel angry at times, take the case and go … still. If we don’t take the case and go then they take out notice saying there is no case. Bring cases, bring cases. We get calls again and again and then they call us to the meeting again and again … bring the case.” (ASHA)

Quality and experience of services

Emphasis on quality-of-service delivery was brought up by nearly all key informants. It was perceived that petitions in the Supreme Court coupled with pressure from academics and NGOs led to the current quality guidelines.Citation39 Studies that had investigated deaths and failures resulting from family planning operations led to two landmark cases in the Supreme Court. Ramakant Rai vs Union of India led the Court to rule the need for uniform guidelines in performance of sterilisation procedures, requirement of informed consent, punitive action for violations and compensation for victims.Citation40 Through Devika Biswas vs Union of India, the Supreme Court ordered the Union of India to ensure discontinuation of sterilisation camps.Citation41

Another key informant pointed out that aside from camps providing poor quality services, government medical colleges as well as hospitals have a lack of hygiene and fail to follow quality guidelines. They felt health facilities were not always well-maintained and infections were commonplace.

“I think that the most important thing, the most important thing, is that this system, that the healthcare system which has been providing family planning since the 50s. It’s a very very long history of providing family planning, the oldest programme in the world. Now if this system could provide quality care, we are all … we have won the game. Quality of care has to be improved.” (Former head, research organisation)

Respondent 1: We have to go back for check up on third day. It is difficult to go back to XXX from here.

Respondent 2: Auto driver charges 600, 700 rupees. If we go once, 600, 800 rupees. …

Respondent 1: Not just about money. It is difficult for the person who has undergone operation to travel. For 600 you have to take so much trouble.

Respondent 2: So they take 200 rupees after operation and come. They don’t go back. (ASHAs)

Historical factors

When talking about the position female sterilisation occupies in Indian family planning, some key informants spoke of the historical factors that framed this position. According to them, a crucial milestone was the development of simpler clinical procedures for female sterilisations which were tested in multi-centre clinical trials. What used to be a regular surgical procedure had been simplified to safer, less expensive and out-patient procedures – either laparoscopically or through the tubal ligation method. Some key informants further felt that gynaecologists and obstetricians formed a powerful constituency in matters relating to family planning and advocated these results to the Government of India.

“… these methods were safe, effective and less expensive. And better for the woman because she just didn’t have to leave her home. Better for the provider because he didn’t have to provide an overnight care for the cost. … Because the Government of India then decided that this was great. And they decided to go all out for sterilisation and specially laparoscopic sterilisation. But you know sometimes intentions are very good but the outcomes are not necessarily in keeping with the intentions because you see although it is indeed possible to do this very quickly, safely, and so on … you know they started doing camps.” (Former head, research organisation)

“The other is … one important thing that happened in the 80s and is not talked about much is that tubectomy became simpler. … women became the focus. You could do camps for women easily, you couldn’t do camps for men easily.” (Head, civil society organisation)

Discussion

A national family planning programme, in some form or other, has existed in India for nearly seventy years. During this time, policy has transformed the programme from being vertically-run, target-driven and focused on population control to one that is supposedly target-free and addresses reproductive rights and health holistically.Citation9 While achieving a declining population growth rate () and TFR,Citation19 what remains unchanged is a reliance on female sterilisation.Citation10 This study highlighted historical factors and social norms that may have situated female sterilisation in becoming the method depended upon to achieve demographic goals. Beyond contextual factors, there appear to be differing discourses at the policy and implementation levels: between wide-ranging choices vs. default choice; encouraging male participation vs. low male sterilisations; target-free vs. expected levels of achievements; and rights-based approach vs population control, respectively. These contrasts help illustrate the role that female sterilisation plays in Indian family planning.

Implicit in India’s national policy commitments is a reproductive rights-based approach which requires an enabling environment where individuals can access information and services on all available methods.Citation10,Citation42 Programme implementation, however, appears to be skewed towards the contraceptive needs of those with one child or more. Four spacing and two limiting methods, in addition to emergency contraception, are currently offered by the programme. The Indian strategy for contraception provision is supposed to have shifted its focus more towards spacing services, except in states with high TFRs.Citation32,Citation33 Incentives remain higher for sterilisation acceptors as compared to those opting for a spacing method like an IUD.Citation6 Most key informants felt female sterilisation becomes a default choice as it is the only option presented to women. Brault et al.Citation30 studied a low-income community in Mumbai where women were found to be overwhelmingly positive about sterilisation; while women voluntarily opted for sterilisation, the study noted the lack of access to reversible contraception as a major reason to do. Physicians interviewed by the authors reported emphasising sterilisation, reflecting an attitude where providers lacked confidence in low-income clients successfully using reversible contraceptive methods.Citation30 In Rajasthan, we found that implementation appears to transform ASHAs into method-specific “motivators”. They admitted to feeling the pressure to motivate and convince women to undergo sterilisation, and particularly, women with two children. Other studies also found that ASHAs promote and prioritise sterilisation due to higher incentives.Citation43

While female sterilisation is the most commonly used method of family planning, sterilisation regret is an issue. SinghCitation22 analysed national-level survey data which revealed an increase in sterilisation regret among ever-married women (15–49 years) from 4.6% (2005–2006) to 6.9% (2015–2016), across rural and urban areas. They noted that women who were either informed of being unable to have children or had experienced child-loss after sterilisation were more likely to express regret. Authors were unclear on whether women understood the permanence of sterilisation but proposed the need for qualitative research on this topic area.Citation4 These findings highlight the need for proper counselling where all relevant information is provided, and suggest that quality and choice are not a reality.Citation22

The Indian strategy for family planning includes “focus on male participation”.Citation33,Citation36 Currently, condoms and vasectomies are the only modern contraceptive methods that men can opt for and make up 17% of all modern methods used.Citation27 Towards the policy imperative to increase the share of male sterilisation to 30% from a current level of 0.3%,Citation36 annual national-level workshops are conducted to develop strategies to encourage male participation; it is not clear whether strategies have been outlined. Vasectomy Fortnights are observed where facilities for rendering vasectomies are operationalised, in addition to Information Education Communication (IEC) mobile vans and sensitisation meetings at the district and block levels.Citation6 There is agreement – among experts and ASHAs, as well as the WHO – that compared to female sterilisation, male sterilisation is “simpler, safer, easier, and less expensive”.Citation44 However, challenges like misinformation, deeply entrenched social norms, and lack of trained human resources were identified by key informants. RISUG - a male contraceptive injectable – is a potential method to be included for men, as mentioned by a key informant. As of late 2019, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) had successfully completed the clinical trials for RISUG and was awaiting regulatory approvals from the Drug Controller General of India.Citation45 There have been no updates since. Global programmatic evidence demonstrates the benefits of involving men in family planning. Effective programmes are often complex, run long-term and require changing gender norms through group education sessions, community outreach and mobilisation, mass-media campaigns, and service-based programmes.Citation46

The current programme, while supposedly target-free, still has method-specific ELAs.Citation41 On the ground, it appears that ASHAs need to contend with target-driven implementation. In our study, an ASHA put across very powerfully that she cannot increase numbers for both pregnant women receiving ANC and women undergoing sterilisation in the same community at a given time, also reflecting a programme that isn’t sensitive to community needs. Supreme Court directives to state governments also emphasise ensuring there are no fixed sterilisation targets, recognising that the pressure of achieving targets could lead to forceful sterilisations.Citation41 Further, these could impact the reproductive freedoms of those who are economically and socially vulnerable. Interviews with ASHAs revealed the pressure they felt to achieve targets and the associated competition they faced with other health workers. Key informants too echoed the need to move away from a target-based approach.

According to policy experts, one of the key components of comprehensive SRH services is quality of care. Most key informants brought up concerns about poor quality of care in service delivery and sterilisation procedures, despite the discontinuation of sterilisation camps.Citation39–41 Joseph et al.Citation28 studied quality of care in sterilisation services at public health facilities in India and found a significant association between household wealth and quality of care. Their results revealed that one in every ten women sterilised at public health facilities received low quality of care; while the percentage is low, it translates to high numbers of women. They also found quality of care to be worse in rural areas.Citation28

The discourse of population explosion that has emerged in a number of senior politicians’ speeches in the last couple of years suggests an implicit anxiety on the government’s part to control population growth.Citation47 Population control has previously taken the form of driving a two-child agenda. In the past, the programme even promoted the popular slogan “Hum Do, Humare Do” (“Us two, our two”).Citation10 BuchCitation48 has written extensively about the consequences of the introduction of the law of the two-child norm in some states for elected representatives in local governments (Panchayats). Buch argues that a policy measure seen to promote smaller families took a coercive form on the ground and disproportionately affected women, the poor, and lower castes from taking up leadership positions.Citation48 The PM’s speech on “population explosion” and Private Member’s bills calling for smaller families appear to be inherently disconnected with upholding a commitment to reproductive rights.Citation16,Citation17 Although the NPP seeks to uphold reproductive health and rights, it promotes a small family norm by providing incentives to couples from poor households to undergo sterilisation.Citation10 National-level survey data suggest that people are voluntarily opting for smaller families, with fertility rates falling across socio-economic and religious groups.Citation27 Yet, as key informants pointed out, the programme continues to approach couples as if they were incapable of making informed reproductive decisions and encourages the strategy of having two children in quick succession, followed by sterilisation. Reproductive rights include the right to choose the number and timing of children, if one chooses to reproduce at all.Citation3 The recent affidavit (2020) filed by the MoHFW in the Supreme Court is reassuring in its emphasis that family planning in India is voluntary and coercion would be counter-productive; this commitment in policy requires broader implementation.Citation18

Strengths and limitations

To understand the role of female sterilisation in Indian family planning, we explored perspectives of policy-makers, academics, members of civil society and ASHAs. There are many other stakeholders, including programme implementers and women who have undergone sterilisation, whose views would have enriched our understanding. While a limited range of stakeholders were involved, findings revealed valuable insights into the reproductive rights narrative in India and brought intersecting views from policy and grassroots realities, highlighting the need for further research. ASHAs’ perspectives on female sterilisation emerged in a study on their broader work and daily experiences. This could be attributed to the methodological advantage that ethnographic research methods lend, including space to build a relationship with the researcher and share on topics they may not otherwise have done. The ethnographic data were, however, collected for different research purposes and, as with any secondary data analysis, there is limited understanding of the context within which the data were generated. Study findings from Rajasthan may not be applicable to other Indian states as health programme implementation is a state subject. Although national policymakers consented to informal discussions, they did not consent to formal interviews, perhaps due to challenges in sharing insights about sensitive topics while in official positions.

Conclusion

Home to 17.5% of the world’s population, India’s health outcomes have an impact on global figures.Citation8,Citation49 India has made substantial strides such as lowered fertility, declining population growth rates, and improved maternal health.Citation9,Citation32 Comprehensive family planning policies and effective programme implementation are therefore crucial to improving national and international trends. Officially, Indian policy language shifted to a rights-based approach in addressing reproductive health and has continued to reaffirm this in global policy commitments and development agendas.Citation9,Citation42 It seems that this supposed policy shift has translated into narrow implementation, given the continued reliance on female sterilisation. There appears to be a continuing negotiation between achieving population stabilisation and upholding sexual and reproductive rights. This study illustrates that achieving sexual and reproductive rights is contingent not just on policy but on how programmes are delivered. The findings in this study hope to serve as points of reflection for family planning policies and programmes and further research. Renewed emphasis on a target-free approach, efforts to educate and supply all available contraceptive choices beyond female sterilisation, creating an enabling environment for voluntary reproductive decision-making, and active involvement of men, are some steps in the direction of upholding reproductive rights and commitments already made in Indian policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

* Publications from the study “The Role of ASHAs in the Private Sector: an Ethnographic Study on Maternal Health in Rajasthan” are in progress and not available for sharing at the moment. Publication references to the initiation of the study are available as follows: (a) Penn-Kekana L, Powell-Jackson T, Haemmerli M, Dutt V, Lange IL, Mahapatra A, Sharma G, Singh K, Singh S, Shukla V, Goodman C. Process evaluation of a social franchising model to improve maternal health: evidence from a multi-methods study in Uttar Pradesh, India. Implementation Science. 2018 Dec;13(1):1-5; (b) Care's profit: precarity and professionalisation of health workers in private maternal clinics in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, India (Isabelle Lange, Sunita Bhadauria, Sunita Singh & Loveday Penn-Kekana) in Childbirth in South Asia: Old Challenges and New Paradoxes, Edited by Clémence Jullien and Roger Jeffery OUP 2021.

† Last author suggested this topic for the first author’s MSc. research project, with secondary analysis of data to provide some insights into the ASHAs’ work on family planning as well as additional policy-level work. Second and last authors identified all in-depth interviews and five group discussions conducted with ASHAs which would be relevant to this study.

‡ Second author conducted a year-long ethnographic study in the district, with supervision by the last author.

References

- Lane SD. From population control to reproductive health: an emerging policy agenda. Social Sci Med. 1994;39(9):1303–1314. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/027795369490362X.

- Sen G, Kismödi E, Knutsson A. Moving the ICPD agenda forward: challenging the backlash. Sexual Reproduct Health Matters. 2019;27(1):319–322. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26410397.2019.1676534.

- Programme of Action adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development Cairo. 20th Anniversary Edition; 2014, 5–13 September 1994. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/programme_of_action_Web ENGLISH.pdf.

- UNFPA. Background document for the Nairobi Summit on ICPD25 - Accelerating the promise; 2019. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/featured-publication/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights-essential-element-universal-health.

- Guttmacher Institute. Sexual and reproductive health and rights indicators for the SDGs: recommendations for inclusion in the sustainable development goals and the post-2015 development process; 2015. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/srhr-indicators-post-2015-recommendations.pdf.

- Department of Health & Family Welfare Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India. Annual Report 2019-20; 2020. Available from: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Annual Report 2019-2020 English.pdf.

- Donaldson PJ. The elimination of contraceptive acceptor targets and the evolution of population policy in India. Popul Stud. 2002;56(1):97–110.

- World Economic Forum. India’s fertility rate has halved since 1980. This is a good sign for the economy; 2018 [cited 2021 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/10/un-report-says-india-s-fertility-rate-has-halved-since-1980-hails-achievement/.

- Visaria L, Jejeebhoy S, Merrick T. From family planning to reproductive health: challenges facing India. International Family Planning Perspectives; 1999 Jan; 25:S44. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2991871?origin = crossref.

- Government of India. National Population Policy; 2000. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/guidelines/nrhm-guidelines/national_population_policy_2000.pdf.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. National Family Planning Programme. [cited 2021 Jan 5]. Available from: https://humdo.nhp.gov.in/about/national-fp-programme/.

- Press Information Bureau Government of India. Health Ministry to launch “Mission Parivar Vikas” in 145 High Focus districts for improved family planning services; 2016. [cited 2019 Mar 24]. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid = 151049.

- Mavalankar D, Vora K. The changing role of auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) in India: implications for maternal and child health (MCH); 2008. Available from: http://www.iimahd.ernet.in/publications/data/2008-03-01Mavalankar.pdf.

- NRHM Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Guidelines on Accredited Social Health Acvtivists (ASHA); 2006. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/communitisation/task-group-reports/guidelines-on-asha.pdf.

- MoHFW, NHSRC. Update on ASHA Programme; 2019. Available from: https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/ASHA Update July 2019.pdf.

- Private member’s bill calls for two-child norm. The Indian Express; July 13, 2019. [cited 2021 Jan 5]. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/private-members-bill-two-child-norm-population-regulation-rakesh-sinha-5827145/.

- Staff writer. PM Modi’s Independence Day speech highlights: India can be a $5 trillion economy in 5 years. Live Mint. [cited 2021 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.livemint.com/news/india/73rd-independence-day-2019-live-updates-pm-narendra-modi-delivers-speech-from-red-fort-1565763102454.html.

- Tripathi A. Centre against involuntary methods for population control, Supreme Court told. Deccan Herald; 2020 Dec 12. Available from: https://www.deccanherald.com/national/centre-against-involuntary-methods-for-population-control-supreme-court-told-926454.html.

- Pradhan MR, Dwivedi LK. Changes in contraceptive use and method mix in India: 1992–92 to 2015–16. Sexual Reproduct Healthcare. 2019;19:56–63. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1877575618302350.

- International Institute of Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey - 5 (2019-21). Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-5.shtml.

- International Institute of Population Sciences, ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai; 2017. Available from: http://rchiips.org/NFHS/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf.

- Singh A. Sterilisation regret among married women in India: trends, patterns and correlates. Int Perspect Sexual Reproduct Health. 2018;44(4):167. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1363/44e7218.

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner India. Census Data; 2011. [cited 2021 Mar 30]. Available from: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdata2011.html.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. Contraceptive use by method 2019: data booklet. United Nations; 2019. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Jan/un_2019_contraceptiveusebymethod_databooklet.pdf.

- Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Jenkins AH. Bangladesh’s family planning success story: a gender perspective. Int Family Plan Perspect. 1995;21(4):132–137, 166. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2133319?origin = crossref.

- DeGraff DS, Siddhisena KAP. Unmet need for family planning in Sri Lanka: low enough or still an issue? Int Perspect Sexual Reproduct Health. 2015;41(4):200–209. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/4120015.pdf.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS - 4). Mumbai. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs4.shtml.

- Joseph KJV, Mozumdar A, Lhungdim H, et al. Quality of care in sterilisation services at the public health facilities in India: a multilevel analysis. Plos ONE. 2020;15(11):e0241499. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241499.

- Choi Y, Khanna A, Zimmerman L, et al. Reporting sterilisation as a current contraceptive method among sterilized women: lessons learned from a population with high sterilisation rates, Rajasthan, India. Contraception. 2019;99(2):131–136. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0010782418304773.

- Brault MA, Schensul SL, Singh R, et al. Multilevel perspectives on female sterilisation in low-income communities in Mumbai, India. Qualitative Health Res. 2016;26(11):1550–1560. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1049732315589744.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 4th ed. London: Sage publications; 2018, p. 440.

- Family Planning Division Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India. India’s Vision FP 2020; 2014. Available from: https://advancefamilyplanning.org/sites/default/files/resources/FP2020-Vision-Document India.pdf.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Government of India. A strategic approach to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH + A) in India; 2013. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/RMNCH+A/RMNCH+A_Strategy.pdf.

- Srinivasan K. Population policies and programmes since independence (a saga of great expectations and poor performance). Demogr India. 1998;27(1):1–22.

- Biswas S. India’s dark history of sterilisation. Delhi: BBC News. [cited 2021 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-30040790.

- Ministry of Heath & Family Welfare. Government of India. National Health Policy; 2017. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid = 4275.

- Jagran News Desk. Independence Day 2020: from Swachh Bharat launch to Article 370 revocation, highlights of PM Modi’s last 6 I-day speeches. Jagran English; 2020 Aug 13; Available from: https://english.jagran.com/india/independence-day-2020-from-swachh-bharat-launch-to-article-370-revocation-key-highlights-of-pm-modis-previous-iday-speeches-10015247.

- Training Programme on Expected Level of Achievement (Target Fixation) for Family Welfare Programmes; 2012.

- Family Planning Division. Standards & Quality Assurance in Sterilisation Services; 2014. Available from: https://www.ukhfws.org/uploads/documents/doc_754_standards-and-quality-assurance(1).pdf.

- ESCR-Net. Ramakant Rai v. Union of India, W.P (C) No 209 of 2003. Available from: https://www.escr-net.org/caselaw/2013/ramakant-rai-v-union-india-wp-c-no-209-2003.

- Devika Biswas v. Union of India & Others, Petition No. 95 of 2012. ESCR-Net. Available from: https://www.escr-net.org/caselaw/2017/devika-biswas-v-union-india-others-petition-no-95-2012.

- Family Planning. India FP2020 Commitments; 2020. [cited 2021 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/india.

- Scott K, Shanker S. Tying their hands? Institutional obstacles to the success of the ASHA community health worker programme in rural north India. AIDS Care. 2010;22(sup2):1606–1612. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540121.2010.507751.

- World Health Organization. Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communications Programs (CCP), Knowledge for Health Project. Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers (2018 update). Baltimore and Geneva; 2018.

- Staff. World’s first injectable male contraceptive, Made in India, could soon be reality. The Wire; 2019 Nov 19. Available from: https://thewire.in/health/risug-injectable-male-contraceptive.

- USAID. FHI360, Progress in Family Planning. Increasing Men’s Engagement to Improve Family Planning Programs in South Asia; 2012. Available from: https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/MaleEngageBrief.pdf.

- Pandey N. BJP MPs say ‘save India’, urge Modi govt to bring in population control law. The Print; 2020 Sep 23. Available from: https://theprint.in/india/bjp-mps-say-save-india-urge-modi-govt-to-bring-in-population-control-law/509248/.

- Buch N. The law of two child norm in panchayats. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company; 2006.

- Khetrapal SP. India has achieved groundbreaking success in reducing maternal mortality; 2018 Jun 10. Available from: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/detail/10-06-2018-india-has-achieved-groundbreaking-success-in-reducing-maternal-mortality.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Codebooks

A. Codebook used for qualitative analysis of secondary ethnographic data on ASHAs

B. Codebook used for qualitative analysis of key informant interviews

Appendix 2. Interview topic guide for key informant interviews

Personal introduction of researcher

Introduction of the research study and participant information sheet

Consent process

Informant introduction

Could you tell me about your experience with (reproductive health/family planning) policy and your present post?

I would first like to ask you some questions on the Indian family planning programme and then move on to some questions focusing on the role of sterilisation in this programme.

National Family Planning Programme

Could you give me your perspective on some of the key family planning issues that India faces?

Do you think that the approach to family planning has changed over the last twenty years – and if so, could you please tell me how this has happened?

Can you tell me some of the key policies that have been put in place in the last two decades to promote family planning?

Could you give me your perspective on these policies?

What have been the successes and challenges you have faced implementing the policy and realising this vision?

According to you, are there variations in the state-level, especially, in Rajasthan with regard to implementing these?

What is your vision for this policy?

Contraceptive methods

I now want to focus more specifically on the role of sterilisation in the programme.

India has high rates of female sterilisation with very young women undergoing this procedure [median age is 25.7 years]. What do you think is the role of female sterilisation in Indian family planning?

When and why do you think female sterilisation has been increasing?

Do you have any concerns about this?

Why do you feel like there are disproportionately high rates of female to male sterilisation?

Role of ASHA workers

I will now move on to the role of ASHA workers in the provision of reproductive health services on the ground.

What do you think is the role of ASHA workers in family planning generally?

Can you tell me what you think is their role in promoting female sterilisation?

Do you think the incentives influence the uptake of female sterilisation?

What do you think needs to be done to improve the quality of family planning services through ASHAs?

Conclusion

Thank you very much for your time and for sharing about your opinions and experience with me. These are all my questions for now. Is there something important that I may have missed out that you feel you would like to tell me from your experience?

In case I have any clarifications regarding what you have shared with me, would it be alright to get in touch with you later on telephonically or in person depending on your convenience?