Abstract

Across low- and middle-income countries, investment in adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) is growing. However, the lack of comprehensive ASRH data hinders programmes. This mapping review examines the available evidence on ASRH in Bangladesh and points out the areas where critical information gaps exist. National surveys, research studies, grey literature, and reports on ASRH in Bangladesh published between 2011 and 2021 were reviewed. Data were extracted into categories, and topical summaries were presented. Research gaps were identified using an analytical framework informed by the Guttmacher Institute’s global summary of ASRH research gaps. The gaps identified were synthesised according to relevance against three of the framework’s categories: coverage, under-reporting and substantive. We also explored the extent to which human rights dimensions of ASRH have been addressed in the literature. While some of the issues covered, such as access to ASRH information, bodily autonomy and self-determination regarding marriage and childbearing choices, clearly address dimensions of human rights, very few studies were found that explored ASRH through a human rights lens. Furthermore, many of the same research gaps identified globally were also evident in the Bangladesh-specific literature. We assert that an expanded ASRH research agenda in Bangladesh that aims to fill the identified evidence gaps would inform more robust, targeted ASRH programming.

Résumé

Dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire, les investissements en faveur de la santé sexuelle et reproductive des adolescents (SSRA) augmentent. Néanmoins, le manque de données globales sur ce thème entrave les programmes. Cet article examine les données disponibles sur la SSRA au Bangladesh et met en évidence les domaines où de graves lacunes existent. Les enquêtes nationales, les études de recherche, la littérature grise et les rapports sur la SSRA au Bangladesh publiés entre 2011 et 2021 ont été examinés. Les données ont été extraites par catégories et des résumés thématiques ont été présentés. Les carences dans les recherches ont été identifiées en utilisant un cadre analytique alimenté par le résumé mondial des lacunes de la recherche sur la SSRA établi par l’Institut Guttmacher. Les manques identifiés ont été synthétisés d’après leur pertinence par rapport à trois des catégories du cadre: couverture, sous-notification et questions de fond. Nous avons également recherché dans quelle mesure les dimensions de la SSRA relatives aux droits de l’homme avaient été couvertes dans les publications. Si certaines des questions couvertes, comme l’accès aux informations sur la SSRA, l’autonomie corporelle et l’autodétermination concernant les choix sur le mariage et la maternité, abordent clairement des dimensions des droits de l’homme, nous avons trouvé très peu d’études qui avaient exploré la santé sexuelle et reproductive des adolescents dans une perspective des droits de l’homme. En outre, beaucoup des mêmes lacunes de recherche identifiées dans le monde étaient aussi évidentes dans les publications propres au Bangladesh. Nous avançons qu’un programme de recherche élargi sur la SSRA au Bangladesh visant à combler les lacunes identifiées guiderait une programmation de santé sexuelle et reproductive des adolescents plus robuste et plus ciblée.

Resumen

En los países de bajos y medianos ingresos, las inversiones en salud sexual y reproductiva de adolescentes (SSRA) están en alza. Sin embargo, la falta de datos completos sobre SSRA obstaculiza los programas. Este artículo examina las evidencias disponibles sobre SSRA en Bangladés y señala las áreas donde existen importantes brechas de información. Se revisaron encuestas nacionales, estudios de investigación, literatura gris e informes sobre SSRA en Bangladés publicados entre 2011 y 2021. Se extrajeron los datos por categoría y se presentaron resúmenes temáticos. Se identificaron las brechas en investigaciones utilizando un marco analítico informado por el resumen mundial del Instituto Guttmacher de brechas en investigaciones sobre SSRA. Se sintetizaron las brechas identificadas según su pertinencia en tres de las categorías del marco: cobertura, subregistro y sustancial. Además, exploramos en qué medida la literatura ha abordado las dimensiones de derechos humanos con relación a la SSRA. Sin duda, algunos de los temas tratados, tales como acceso a información sobre SSRA, autonomía corporal y autodeterminación con respecto a las opciones de matrimonio y maternidad, abordan las dimensiones de derechos humanos; sin embargo, se encontraron muy pocos estudios que exploran la SSRA desde la perspectiva de los derechos humanos. Muchas de las mismas brechas en investigaciones identificadas mundialmente también eran evidentes en la literatura específica a Bangladés. Sostenemos que una agenda ampliada de investigación sobre SSRA en Bangladés, que se proponga llenar las brechas de evidencias identificadas, informaría programas de SSRA más robustos y focalizados.

Introduction

In Bangladesh, adolescents make up slightly over one-fifth of the population and their number stands at more than 32 million.Citation1 The high prevalence of child marriage and adolescent childbearing limit young women’s educational attainment and lifelong income potential. There is also limited access to adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) counselling and services and existing services.Citation2 However, ASRH was not a policy priority until recently. A National Strategy for Adolescent Health was launched in 2017, and adolescents are now formally recognised as an important demographic group with unique needs and potential and constitute a high priority group for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) of Bangladesh.

The National Strategy has four technical pillars: sexual and reproductive health (SRH), nutrition, violence, and mental health. Adolescent-friendly health services have begun to be made available nationwide at primary care level facilities within the past five years. These consist of information, counselling, and treatment for a range of health issues, including menstruation, anaemia, and reproductive tract infections. Family planning information and services are included in the service package; however, social, cultural, and policy barriers limit access for unmarried adolescents. Though ASRH services are still new, an analysis of adolescent clients indicates that girls may be more likely to utilise adolescent-friendly health services than boys.Citation3 Once married, adolescents tend to be treated as adults in their interactions with the health system. On the one hand, this facilitates their access to and use of family planning services. On the other hand, it may limit married adolescents’ ability to benefit from health messaging, materials and services tailored to their age and associated interests and needs.

In addition to adolescent-friendly health services, national-level system strengthening efforts are being made through a partnership between the MOHFW, the Obstetrics and Gynecological Society of Bangladesh, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, UNICEF, UNFPA, and development partners. The priorities of this partnership are: to strengthen the evidence base on adolescent health issues through operations research; integrate indicators on adolescent health into the national health information system; develop a training and accreditation system for adolescent-friendly health service providers; and oversee a coordination structure on adolescent health at national and sub-national levels. Apart from this project, a national School-Based Adolescent Health Program is underway. Finally, an increasing number of donor-funded and non-governmental organisation-led projects are working on providing tailored information and services to meet ASRH needs, including delaying marriage and childbearing and fostering greater gender equality.Citation4 However, compared to those for adolescent girls, targeted programmes for male adolescents have often been neglected.Citation5

The increased prioritisation of ASRH in Bangladesh parallels the expansion of ASRH programmes in many other countries framed by the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030). Coupled with this have been significant investments in data collection and analysis on ASRH to better understand adolescents’ varying needs and which types of programmatic interventions are most effective. Yet, while quality data have broadened the body of knowledge on ASRH, many gaps remain. The existence of gaps in ASRH evidence is true globally and in the context of Bangladesh. As outlined in the Guttmacher Institute paper, Research Gaps in Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health,Citation6 coverage, under-reporting, and substantive gaps in national-level household surveys across countries impede a complete understanding of adolescents’ SRH knowledge, behaviours, and service use patterns. In addition to that, the absence of longitudinal qualitative data, in-depth narratives, and qualitative studies on this area are few. Further, despite the growing body of research on effective intervention models, there is not yet enough certainty about what works to adequately inform where to channel resources most efficiently and how to scale up effectively.Citation6–9 This review on ASRH, in the context of Bangladesh, would add substantially to the literature on what is missing and what gaps exist.

Rationale and objectives

Given the tremendous investments in ASRH in Bangladesh, there is a need for quality evidence to prioritise, target, tailor, monitor, and evaluate current and future ASRH interventions. In this paper, we review the literature on the status of ASRH in Bangladesh, intending to identify critical information gaps and priorities for future data gathering. The components of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), as defined in the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission, are gender-based violence, HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), contraception, maternal and newborn health, abortion, infertility, and reproductive cancers. Adolescent SRHR addresses the particular needs that young people face when they reach sexual maturity and gender roles and norms intensify and solidify. The foundation for a healthy sexual and reproductive life is laid. During this time, child marriage and pregnancy have a particular impact on women globally, while at the same time, barriers to accessing SRHR services are common.Citation10 Since ASRH is more than a concern solely with diseases and problems, we have also examined how human rights dimensions of ASRH have been addressed in the available evidence. Specifically, we examined the coverage of issues such as restricted access to ASRH education and services, child marriage, coerced sex, and sexual abuse.

Using the gaps identified by the Guttmacher Institute in ASRH behavioural research across countries as an analytical framework (), we aimed to identify the degree to which these same gaps exist within the literature on ASRH in Bangladesh.Citation6 In addition, we also looked for gaps related to the human rights dimensions of ASRH. The present study builds upon a review initially carried out by UNFPA Bangladesh in 2018 to support its programmatic efforts in the country. We have subsequently developed this into an article to guide future ASRH data collection activities across in-country stakeholders. We hope to provide policy-makers, donors, programme managers, and researchers with a set of priority areas to focus on when designing and investing in future ASRH data collection and analysis activities. The larger goal of doing so is to contribute to the current momentum within the ASRH programmatic landscape to generate richer and more nuanced datasets that can broaden and sharpen the landscape of adolescent health programming in Bangladesh. summarises the evidence gaps in developing regions identified by the Guttmacher Institute. These were used as a reference for our analysis.Footnote*

Table 1. Research gaps in adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing regions

Methods

We undertook a mapping review of published and grey literature on ASRH in Bangladesh. A mapping review is a method used to give a broad, thorough examination of a particular topic.Citation11 It is uniquely applied in literature reviews to identify gaps in research areas and where further primary or secondary research may be needed.Citation12

Selection of evidence

In selecting evidence, emphasis was placed on nationally representative surveys published in English between 2011 and 2019 for the first phase. Subsequently, we have included eligible articles, reports, and factsheets published from January 2020 to December 2021 to update the search. Research studies and reports published during the same period were also gathered to provide greater context around the survey data. The relevant surveys were already in the researchers’ possession at the start of the review and were used as the primary data sources. Each survey was reviewed for its inclusion of information about young people between the ages of 10 and 19. The key SRH measures identified in each survey were extracted into separate tables for analysis. The research studies and analytical reports on ASRH in Bangladesh were reviewed to shed more light on topics that were not comprehensively covered in national surveys (e.g. premarital sexual behaviour, sexual harassment, cervical cancer, etc.). The published and grey literature thus provided details and context around many of the surveys’ key measures.

Search strategy

Keyword searches using the phrase “adolescent sexual and reproductive health Bangladesh” were conducted using the open-access scholarly databases PubMed, ScienceDirect, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOJA), The Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. Where searches resulted in extensive listings of articles with an international focus rather than a specific focus on Bangladesh, results were narrowed down using the databases’ advanced search tool to reflect only articles with Bangladesh as the central focus. Reference lists from key articles were scanned to identify other relevant articles not found in the initial search. Only open-access databases were searched, which was a limitation of this review, as was the choice to limit the search strategy to a single phrase, as opposed to using more specific terms with Boolean operators. The initial search for the development of the report was carried out in April 2018. The search was repeated in July 2019 and again in February 2021 to check for replicability and identify new publications.

A search for analytical papers, briefs, and reports published by professional organisations working on ASRH in Bangladesh was also conducted. We contacted organisations working on ASRH in Bangladesh via email and held discussions by phone and/or in-person with Dhaka-based staff of each organisation to ask about any recent relevant publications. Organisations’ websites were also scanned for any downloadable reports on ASRH in Bangladesh, and those reports’ reference lists were reviewed for additional relevant publications. The website scan was repeated in July 2019 and again in June 2020. Despite casting the net wide, it is possible that some studies or reports were missed, particularly reports developed for internal use by donors or national agencies but not publicly disseminated.

Exclusion criteria

Research published prior to 2010 was excluded as it was considered too old to be directly relevant to current ASRH programme needs. Some national surveys that were conducted between 2011 and 2019 were excluded if a more recent survey covering the same topics was available. Studies analysing data collected prior to 2011 were excluded. Content in the grey literature that was duplicative of that already available in the selected national surveys (e.g. level of schooling, marriage age, childbearing age, adolescent girls’ receipt of antenatal care) was excluded from the analysis as well. A systematic quality assessment of articles was not carried out. However, a small number of articles were manually excluded because their research questions or methods were misaligned with the definition of ASRH that we used to shape the review.

Search results

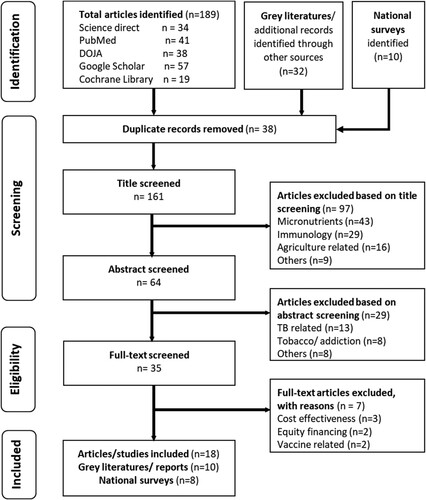

Eight reports describing national survey data were included in the review. They were the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2019, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys (BDHS) from 2017/2018 and 2014, the Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey (BMMS) 2016, the Violence Against Women Survey (VAW) 2015, the Global School-based Student Health Survey 2014, and a 2021 survey report on male youth and their perceptions on SRHR. Two national survey reports were excluded – the Urban Health Survey 2013 and the Report on Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics 2016 – as they included measures duplicative of those already available in the more recent BDHS and MICS. Despite these surveys’ inherent value, it was thought that incorporating them would add complexity in presenting the national picture of ASRH due to their methodological differences from the national fertility and health surveys. The initial and updated database search generated 161 articles. Duplicates were removed and articles were scanned for topical relevance. Eighteen published articles on ASRH in Bangladesh were finally included. In addition, 10 reports were added, which were identified through the organisational outreach and websites scans, including a recent report on a mixed-methods nationwide study on ASHR 2019. The following flow diagram depicts the narrowing down of the selected literature from the different sources ().

Synthesis of findings

The analysis consisted first of classifying each type of study according to whether they were surveys, published articles or grey literature, and identifying their relevant content. Quantitative data from national surveys were considered appropriate if they reported on an SRH topic among young people 10–19 years of age. Quantitative and qualitative data from grey literature were considered relevant if they complemented national surveys by broadening and deepening the overall picture of ASRH in Bangladesh. The topics identified were marriage, sexual debut, childbearing, maternal health, family planning, abortion, STIs, cervical cancer, gender-based violence, harassment, and bodily autonomy. Bodily autonomy is defined as the ability of persons to make their own choices about their bodies and futures.Citation13 It also includes perceived or actual control over one’s own life, inclusive of individual empowerment to make choices over health care, contraception and the ability to say yes or no to sex. The results within each SRH topic area were extracted and populated in a separate table for analysis. Narrative summaries of the extracted data were developed for each sub-topic and then combined into a single summary. The specific gaps in the ASRH research in Bangladesh were then identified by examining the topics covered against the analytical framework. Each co-author reviewed a set of articles assigned to them and completed a standard data extraction tool (checklist) indicating whether the identified topics were adequately reflected in each paper. Completed checklists from all co-authors are summarised in .

Table 2. Information gaps on adolescent sexual reproductive health behaviours in Bangladesh

Findings

What we know

Premarital sexual behaviour

There is very little information available about whether and in what context sexual debut among adolescent boys or girls may occur prior to marriage. According to results for Bangladesh from the Global School-based Health Survey, 9.4% of students aged 13–17 have had sexual intercourse, with boys being much more likely to report having had sex than girls.Citation18 Apart from this, statistics about premarital sex do not exist in other national surveys, as married women consistently report their first sexual intercourse happening after marriage, and unmarried women are not asked about sexual behaviour.Citation19

However, various non-nationally representative studies have documented a low prevalence of premarital sexual activity among both boys and girls and a higher prevalence among boys living in slums and young men aged 15–24 living on the street, including both selling and paying for sex.Citation20,Citation21 One study reported significant concerns among parents, teachers, and community members in Chittagong about premarital romantic relationships and the possibility of young people making “mistakes” (i.e. having sexual intercourse) within these relationships.Citation22 Another study used qualitative methods to explore the contexts in which unmarried adolescent boys and girls (aged 12–18) in one city feel and experience their sexuality. Both boys and girls described dating and intimate encounters with romantic partners and shared that, while not common, sexual intercourse between young dating partners was not unheard of. However, boys living in slums were the most likely to report having had sexual intercourse. Respondents, both boys and girls, expressed curiosity and excitement in discussing their desire for sexual activity. At the same time, they described feelings of guilt about their experiences of their sexuality and stated that sexual desire and premarital sex are wrong.Citation23

Child marriage

Over half (51%) of 20-24-year-old girls were married by age 18.Citation24 While child marriage is strongly associated with low levels of education, one large-scale study with 10,503 respondents across 14 of the country’s 64 districts found that more than 70% of respondents perceived that women’s and girls’ primary function was to bear and raise children and that girls earn their identity and social status within their communities through marriage.Citation25 In spite of these figures, there is an overall declining trend in child marriage; the median age at first marriage among women aged 20–49 was 15.3 years in 2007 and increased to 16.3 years in 2017.Citation19 Adolescent marriage among boys is virtually non-existent, with boys predominantly marrying after age 20. Marriage before age 18 is more common in rural than in urban areas.Citation24 While not reported on in the recent demographic surveys such as 2017/2018 BDHS or the 2019 MICS, the 2014 BDHS reported young women’s preferences regarding their marriage age. The data indicated that 60% of 15-17-year-olds and 41% of 18–20-year-olds would have preferred to marry later than they did. Later age at marriage was strongly associated with higher educational attainment and greater wealth.Citation19,Citation26 Living in humanitarian settings also moulded adolescent behaviours. One qualitative study explored factors influencing early marriage practices such as the low status of women and girls in society, religious norms and limited alternatives that are persistent amongst Rohingya refugees.Citation27

Adolescent childbearing and preferences

Adolescent childbearing (the percentage of married 15-19-year-old girls who have begun childbearing) has shown a steady decline from about 33% in 2007, to 31% in 2014, and 28% in 2018.Citation19 While not reported in the 2017/2018 BDHS, the 2014 BDHS indicates that adolescents’ ideal is to have two children. In 2014, about a fifth of adolescent mothers reported that they would have preferred to delay childbearing.Citation26

Maternal health

Analysis of maternal and newborn health data reveals that adolescents in Bangladesh enter pregnancy with greater risks, receive less and lower quality medical care, and have more adverse outcomes than adult women.Citation16,Citation28 In addition, undernutrition is widespread among adolescent girls. This increases their risk of complications during delivery and of having a low-birth-weight baby. Various studies indicate an undernutrition prevalence close to 33% for both urban and rural adolescent girls.Citation29 The latest survey data indicate that adolescents have lower levels of knowledge about maternal complications than adult women, and their knowledge increases with age. Adolescents are also slightly less likely to have blood or urine samples taken during antenatal care (ANC) visits and more likely to deliver at home than hospital or clinic.Citation28 Decision-making about the receipt of ANC services and place of delivery appears to be largely directed by married adolescents’ husbands and mothers-in-law. Indeed, the research shows that family tradition and views toward maternal health care influence this choice, and the decision not to seek ANC services and deliver at home is common.Citation30

Family planning

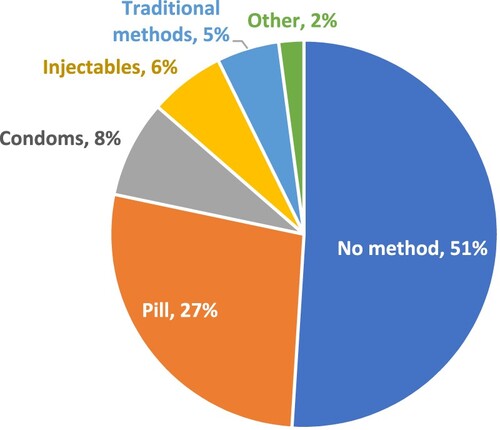

Nationally, 48% of married girls aged 15–19 use a modern method of contraception.Citation24 The primary method used is the birth control pill, followed by condoms, and injectables (). Approximately 5% of married adolescents use traditional methods and 51% do not use any form of contraception. Research that has explored factors influencing married adolescents’ decision-making around contraceptive use found that adolescents’ husbands and mothers-in-law are key decision-makers for both contraceptive use and childbearing. It was also found that lack of effective communication between husband and wife, as well as with other family members, and mistrust toward contraceptive methods were also influential factors.Citation30 Between 2014 and 2018, the use of modern methods (particularly the contraceptive pill and injectables) among 15–19 years old girls declined slightly, while the use of condoms, implants, and traditional methods increased slightly.Citation19

Figure 2. Contraceptive method mix among married adolescent girls age 15–19 (N = 2006). Source: BDHS 2017/2018.

The private sector is a fast-growing source of contraceptive methods. Oral contraceptive pills and condoms are most frequently sourced from private pharmacies, though government field workers are also important suppliers of contraceptive pills. Injectables are commonly supplied both in the public and private sectors, while implants are almost exclusively supplied through the public sector.Citation19

The unmet need for family planning among married 15-19-year-old girls stands at 18%. This is noticeably higher than all other age groups; the overall unmet need for family planning (across age groups) is 14%.Citation24 Basic awareness among adolescents about family planning is widespread, in particular awareness of the oral contraceptive pill.Citation19 Knowledge among married adolescents may be higher than among those not yet married, though various studies indicate that this knowledge is limited.Citation31 For example, Cortez et alCitation32 found that among married adolescent girls living in slums in Dhaka, only 10% had heard of emergency contraception, and the methods which respondents were aware of coincided with those that they were using. Findings in another study by Huda et alCitation33 corroborate this; inconsistent use of family planning methods, and lack of awareness about available methods were the primary reasons for unintended pregnancies among married adolescent girls in Dhaka slums. Other reasons for unmet needs described in this study included fear of side effects, uncertainty about where to obtain contraception, lack of funds to purchase contraception, no or infrequent sex with husband, post-partum amenorrhoea, breastfeeding, and opposition from husband.Citation33

STIs, cervical cancer and menstrual regulation

Data on STIs and cervical cancer among adolescents were limited to studies that documented adolescents’ low levels of knowledge about these topics.Citation34–36 While the use of menstrual regulation (MR)Footnote† services was not reported in the 2019 MICS and 2017/2018 BDHS, the 2014 BDHS reported that both knowledge and use of MR were lower among adolescents compared to adult women.Citation26 Hossain et alCitation25 reported in a study that the availability of MR services might be declining due to lack of training among newly recruited younger (i.e. aged 20–29) health care providers.Citation37 Another reason could be the stigma around reporting that the interviewed women knew where the MR services were available or had used these services. Despite being legal for 10–12 weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period, MR is still socially frowned upon in Bangladesh.Citation38 It is also possible that some facilities, especially private clinics, do not disclose that they provide MR services, primarily due to legal issues.Citation38

Gender-based violence

It is common for adolescent girls to experience violence perpetrated by partners and non-partners. The 2015 VAW survey reported that 28% of adolescent girls had experienced either physical or sexual violence perpetrated by their partners within the last 12 months, and 43% had at some point in their lifetime. Moreover, the survey highlighted that non-partner physical violence in the previous 12 months was 11.2% and non-partner sexual violence was 3.1% among adolescents aged 15–19 years. These rates were the highest and second-highest, respectively, when compared with all other age groups.Citation39

Significant numbers of married adolescent girls believe that spousal abuse is acceptable. For example, a study among adolescent girls living in Dhaka slums found that close to 30% believed it was justified for a husband to beat his wife if she went out without telling him. A higher 35% believed that it was acceptable for a husband to beat his wife if she did not care for the house or the children. Over half (55%) believed a husband could beat his wife if she showed disrespect toward her in-laws.Citation32

Bodily autonomy, harassment and emotional distress

Some research indicates that bodily autonomy, including the right to choose when to marry and have children and freedom of movement, may not be a reality for many adolescent girls. Public sexual harassment of girls, commonly referred to as “Eve teasing” in Bangladesh and in several other South Asian countries, is discussed in the literature as being a common phenomenon. It is usually initiated by boys and men and directed at girls and women and causes significant anxiety for adolescent girls.Citation40 One study explored this topic in-depth, finding that sexual harassment is a mode of experiencing sexual pleasure and demonstrating their masculinity for adolescent boys. Girls, however, disliked the harassment because it provoked insecurity. The authors asserted that this type of sexual harassment is a result of restrictions on social interactions between the sexes and is exacerbated by pornographic media and a lack of sexuality education. They further argue that these forces impede the development of competence in establishing mutually rewarding intimacy.Citation23 Other studies also indicate distress among adolescent boys and young men connected to social norms associated with masculinity. In a national survey on SRHR perceptions and masculinity, three-fourths of young males reported being worried about their sexual performance, propelling them into anxiety and worries.Citation41 One study reported that male suicide in rural Bangladesh was attributable to men’s inability to live up to norms of masculinity, such as financial provision and meeting the sexual needs of their spouses.Citation42

Sexual harassment of girls is found to affect their families as well, who fear social repercussions from their community. Fear of social repercussions, in turn, discourages reporting and pursuing punishment for perpetrators. In some cases, families of girls who have been sexually harassed by influential individuals face legal complications that serve as impediments to obtaining justice.Citation43 These studies, however, mentioned very little about cyberbullying, peer bullying, and suicidal tendencies due to the emotional distress that some adolescents face in Bangladesh.

What we don’t know

details the number of studies that include the ASRH research gap areas outlined in the analytical framework () and the information gaps on these topics specific to Bangladesh.

Discussion

Overall, our analytic framework allowed us to systematically identify the coverage, under-reporting, and substantive gaps identified in the Bangladesh literature that correspond with the research gaps in developing regions. We particularly highlighted three gaps to illustrate ASRH situations in Bangladesh, such as coverage gaps (for unmarried/never-married women, adolescents younger than 15, adolescent boys, and youth in vulnerable situations), under-reporting gaps (sexual activity among adolescents and induced abortion), and substantive gaps (human rights dimensions of ASRH, health impacts of adolescent pregnancy and childbearing, long-term economic effects of teenage childbearing, adolescent pregnancy and childbearing intentions, reasons for unmet need for contraception) according to our adopted analytical framework. This framework is useful to identify gaps, and the salience of examining the extent to which the human rights dimensions of ASRH have been addressed in the studies. However, much of the evidence is descriptive, providing a big picture of what is happening, but without an analytical and in-depth exploration of nuance and unique sub-groups that can provide important insights that can directly inform targeted interventions.

Human rights dimensions of ASRH were touched upon most in the papers reviewed. The Guttmacher Institute paper that informed the analytical framework described human rights contexts of ASRH as violations in which child marriage, coerced sex, and sexual abuse occur yet remain undocumented. Across the Bangladesh literature, rights violations, such as limited access to SRH education and information, discrimination in service access based on age and marital status, sexual harassment, violence, and lack of self-determination in decision-making about marriage, childbearing and maternal health service use, were substantially reflected. Yet, despite the significant number of papers that were identified that discuss human rights-related topics, there were still information gaps. For example, coerced sex and sexual abuse discussed outside the context of child marriage were not reflected in the Bangladesh literature. Furthermore, none of the studies adopted a human rights-based approach to examine ASRH. Rather, their content described ASRH issues and challenges.

Ultimately, an expanded research agenda is needed to begin to close the ASRH evidence gaps in Bangladesh. In order to design effective programmes, policy-makers and health managers need to know the needs of their target populations. Continued adolescent-specific analyses of national datasets, such as this paper, are essential to carry out alongside national demographic and health surveys. Therefore, we recommend more in-depth research, longitudinal qualitative research, and other social science research on ASRH services to inform programme and policy designs.

Topics to explore further could include factors influencing adolescents’ preferences regarding timing of marriage and childbearing, barriers and facilitators to family planning service utilisation, knowledge about sexually transmitted infections, premarital sexual experiences, SRH-related emotional distress, online encounters, norms around coercion and consent, and the unique issues facing gender and sexual non-conforming groups. Surveys and research studies on SRH could enable collecting disaggregated data on various adolescent age groups, such as girls ages 10–14, unmarried girls ages 15–19 and boys ages 10–19, which are also important to address through a targeted programme approach. To ensure vulnerable groups are represented in national SRH datasets and representative sub-groups of adolescents can be compared with one another, routine implementation of an adolescent and youth survey may be a useful avenue to pursue.

In addition, more research should be carried out that includes qualitative and in-depth quantitative data collection to improve understanding of the complex web of issues that affect reaching adolescent sexual and reproductive goals. Adolescents’ high unmet needs and marriage timing preferences could be further explored in these types of studies, as well as deeper dimensions of ASRH rights that are missing in the current literature, including bodily autonomy, self-determination, sexual coercion, and abuse. In addition, adolescents’ experiences of well-being are critical if they have to encounter some complex situations in their lifetime, such as experiences of cyberbullying, peer bullying, and emotional distress. All of these negatively impact individuals’ SRH care-seeking. Studies like these could help deepen understanding of the full context of ASRH, particularly for unmarried, vulnerable, and younger adolescents, in order to inform interventions that can make a lasting difference.

Limitations

Limitations of this paper include a simple keyword search strategy rather than the methods employed for systematic or scoping reviews. We were also limited to using open-access databases. In addition, there are limitations in relying on small cross-sectional surveys to identify gaps that may have been reflected in the findings. There is also a possibility that the choice of the analytical framework, while helpful, may have meant that other issues were not identified.

Conclusions

In summary, while traditional ASRH topics related to married adolescents are well covered, gaps in all three categories – coverage, under-reporting and substantive – are significant. Future research should focus on different types of intervention approach for the diverse contexts in the country, and the heterogeneity of adolescents should be rigorously evaluated to generate evidence. Such evidence can inform policy-makers to guide, replicate and scale-up evidence-based interventions at national and sub-national levels in Bangladesh.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

* We have added the “human rights dimensions of sexual and reproductive health” to the substantive gaps, and this modified version serves as our frame of reference to assess the ASRH information gaps in Bangladesh.

† Menstrual regulation (MR) is a procedure to reestablish the menstrual cycle after it has been absent for a short period of time.

References

- UNICEF Bangladesh. (2022). Adolescents in development. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/en/adolescents-development

- Zakaria M, Karim F, Mazumder S, et al. Knowledge on, attitude towards, and practice of sexual and reproductive health among older adolescent girls in Bangladesh: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7720.

- Ainul S, Ehsan I, Tanjeen T, et al. Adolescent women’s need for and use of sexual and reproductive health services in developing countries; 2017. Available from: https://evidenceproject.popcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Bangladesh-AFHC-Report_2017.pdf

- Hasan M, Rahman M. Health behaviors among the adolescents in Bangladesh: evidence from a nationwide survey. Hum Biol Rev. 2020;9:261–280. Available from: http://www.humanbiologyjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Volume9-Number3-Article5.pdf

- Ainul S, Bajracharya A, Reichenbach L, et al. Adolescents in Bangladesh: a situation analysis of programmatic approaches to sexual and reproductive health education and services; 2017.

- Darroch JE, Singh S, Woog V, et al. Research gaps in adolescent sexual and reproductive health; 2016. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/research-gaps-in-sexual-and-reproductive-health

- Haberland NA, McCarthy KJ, Brady M. A systematic review of adolescent girl program implementation in low- and middle-income countries: evidence gaps and insights. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:18–31.

- Salam RA, Das JK, Lassi ZS, et al. Adolescent health interventions: conclusions, evidence gaps, and research priorities. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:S88–S92.

- Woog V, Alyssa B, Jesse P. Adolescent women’s need for and use of sexual and reproductive health services in developing countries; 2015. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.718.7866&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2642-92.

- Cooper ID. What is a “mapping study?”. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104:76–78.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26:91–108.

- UNFPA. Intergenerational action for bodily autonomy: accelerating sustainable development goal 3; 2021. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/events/HLPF2021

- Brac University. Inclusion of persons with disabilities: Bangladesh perspective; 2019.

- Hasan T, Muhaddes T, Camellia S, et al. Prevalence and experiences of intimate partner violence against women with disabilities in Bangladesh: results of an explanatory sequential mixed-method study. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29:3105–3126.

- Godha D, Hotchkiss DR, Gage AJ. Association between child marriage and reproductive health outcomes and service utilization: a multi-country study from South Asia. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:552–558.

- BIGD. Gender and adolescence: global evidence (GAGE) research program; 2021.

- Global school-based health survey; 2014. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/2014-Bangladesh-fact-sheet.pdf

- Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2017–18; 2019. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR104/PR104.pdf

- Amin S. Urban adolescents needs assessment survey in Bangladesh; 2015. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy/648/

- McClair TL, Hossain T, Sultana N, et al. Paying for sex by young men who live on the streets in Dhaka city: compounded sexual risk in a vulnerable migrant community. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:S29–S34.

- Mitu K, Uddin MA, Camfield L, et al. Adolescent health, nutrition, and sexual and reproductive health in Chittagong, Bangladesh; 2019. Available from: https://www.gage.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Chittagong-Health-Policy-Note_final.pdf

- Nahar P, Van Reeuwijk M, Reis R. Contextualising sexual harassment of adolescent girls in Bangladesh. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:78–86.

- Pathey P. Bangladesh multiple indicator cluster survey; 2019. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/en/reports/progotir-pathey-bangladesh

- Hossain M, Nabi A, Ghafur T, et al. Context of child marriage and its implications in Bangladesh; 2017. Available from: http://dpsdu.edu.bd/images/ChildMarriageReport.pdf

- Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014; 2016. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR311/FR311.pdf

- Melnikas AJ, Ainul S, Ehsan I, et al. Child marriage practices among the Rohingya in Bangladesh. Confl Health. 2020;14:28.

- Bangladesh maternal mortality and health care survey 2016; 2016. Available from: http://rdm.icddrb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/BMMS-2016-Final-Report_10-Feb-2020.pdf

- Stavropoulou M., Marcus R., Rezel E., Gupta-Archer N. and Noland C. Adolescent girls’ capabilities in Bangladesh: the state of the evidence on programme effectiveness. 2017. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence. https://www.gage.odi.org/publication/adolescent-girls-capabilities-bangladesh-state-evidence-programme-effectiveness/

- Shahabuddin A, Nöstlinger C, Delvaux T, et al. Exploring maternal health care-seeking behavior of married adolescent girls in Bangladesh: a social-ecological approach. PloS one. 2017 Jan 17;12(1):e0169109.

- Shahabuddin AS, Nöstlinger C, Delvaux T, et al. What influences adolescent girls’ decision-making regarding contraceptive methods use and childbearing? A qualitative exploratory study in Rangpur District, Bangladesh. PloS one. 2016 Jun 23;11(6):e0157664.

- Cortez R, Hinson L, Petroni S. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Dhaka's slums, Bangladesh. The World Bank; 2014. https://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/hnpkbs/91291.html

- Huda FA, Chowdhuri S, Sarker BK, et al. Prevalence of unintended pregnancy and needs for family planning among married adolescent girls living in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2014. Available from: https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2014STEPUP_MarriedAdolescent_Dhaka.pdf

- Das AK, Roy S. Unheard narratives of sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) of adolescent girls of the Holy Cross College, Dhaka, Bangladesh. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci. 2015;21:1–8.

- Hossain M, Mani KK, Sidik SM, et al. Knowledge and awareness about STDs among women in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1–7.

- Islam JY, Khatun F, Alam A, et al. Knowledge of cervical cancer and HPV vaccine in Bangladeshi women: a population based, cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:1–13.

- Hossain A, Maddow-Zimet I, Ingerick M, et al. Access to and quality of menstrual regulation and postabortion care in Bangladesh: evidence from a survey of health facilities, 2014; 2017. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/menstrual-regulation-postabortion-care-bangladesh

- Guttmacher Institute. Face sheet: menstrual regulation and unsafe abortion in Bangladesh; 2017. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/menstrual-regulation-unsafe-abortion-bangladesh

- Report on violence against women survey 2015; 2016. Available from: https://evaw-global-database.unwomen.org/en/countries/asia/bangladesh/2015/report-on-violence-against-women-vaw-survey-2015

- Mitu K, Ala Uddin M, Camfield L and Muz J. ‘Adolescent bodily integrity and freedom from violence in Dhaka, Bangladesh.’ 2019. Policy Note. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence. https://www.gage.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Chittagong-Policy-Note-Bodily-Integrity_final.pdf access on 5th June 2022.

- Misha FA, Rashid SF. Fact Sheet: Male youth and their sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in Bangladesh: a mixed methods nationwide study; 2019. Available from: https://bracjpgsph.org/assets/pdf/Advocacy/communication%20tools/ADDRESSING-SDGs/Fact%20Sheet_Male%20Youth%20and%20Their%20Sexual%20And%20Reproductive%20Health%20And%20Rights%20(SRHR)%20in%20Bangladesh.pdf

- Khan AR, Ratele K, Helman R, et al. Masculinity and suicide in Bangladesh. OMEGA J Death Dying. 2020; 20. doi: 10.1177/0030222820966239.

- Mitu K, Ala Uddin M, Camfield L and Muz J. Adolescent bodily integrity and freedom from violence in Chittagong, Bangladesh; 2019. Available from: https://www.gage.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Chittagong-Policy-Note-Bodily-Integrity_final.pdf