Abstract

Self-care interventions for health are becoming increasingly available, and among the preferred options, including during the COVID-19 pandemic. This research assessed the extent of attention to laws and policies, human rights and gender in the implementation of self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health (SRH), to identify where additional efforts to ensure an enabling environment for their use and uptake will be useful. A literature review of relevant studies published between 2010 and 2020 was conducted using PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. Relevant data were systematically abstracted from 61 articles. In March–April 2021, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 key informants, selected for their experience implementing self-care interventions for SRH, and thematically analysed. Laws and policies, rights and gender are not being systematically addressed in the implementation of self-care interventions for SRH. Within countries, there is varied attention to the enabling environment including the acceptability of interventions, privacy, informed consent and gender concerns as they impact both access and use of specific self-care interventions, while other legal considerations appear to have been under-prioritised. Operational guidance is needed to develop and implement supportive laws and policies, as well as to ensure the incorporation of rights and gender concerns in implementing self-care interventions for SRH.

Résumé

Les interventions d’auto-prise en charge deviennent de plus en plus largement disponibles et comptent parmi les options préférées, notamment pendant la pandémie de COVID-19. Cette recherche a évalué le degré d’attention accordée aux lois et politiques, aux droits de l’homme et au genre dans la mise en œuvre des interventions d’auto-prise en charge pour la santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR), afin d’identifier les points où des efforts supplémentaires seront utiles pour assurer un environnement habilitant pour leur utilisation. Un examen des études pertinentes publiées depuis 2010 a été mené à l’aide de PubMed, Scopus et Web of Science entre 2010-2020. Les données intéressantes de 61 articles ont été résumées de manière systématique entre Mars-Avril 2021. Des entretiens semi-structurés ont été réalisés avec dix informateurs clés, choisis pour leur expérience dans la mise en œuvre d’interventions d’auto-prise en charge pour la SSR, et analysés de manière thématique. Les lois et les politiques, les droits et le genre ne sont pas abordés systématiquement dans la mise en œuvre des interventions d’auto-prise en charge pour la SSR. Les pays accordent une attention différente à l’environnement juridique, notamment l’acceptabilité des interventions, le respect de la vie privée, le consentement éclairé et les préoccupations de genre dans la mesure où ces questions influent aussi bien sur l’accès que l’utilisation des interventions spécifiques d’auto-prise en charge, alors que d’autres considérations juridiques semblent avoir été sous-priorisées. Des recommandations opérationnelles sont nécessaires pour élaborer et appliquer des lois et politiques favorables, ainsi que pour garantir l’inclusion des droits et des préoccupations de genre dans la mise en œuvre des interventions d’auto-prise en charge pour la SSR.

Resumen

Las intervenciones de autocuidado de la salud están cada vez más disponibles y figuran entre las opciones preferidas, incluso durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Esta investigación evaluó el grado de atención a leyes y políticas, derechos humanos y género en la aplicación de intervenciones de autocuidado de la salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR), para identificar dónde serán útiles esfuerzos adicionales por garantizar un entorno favorable para su uso y aceptación. Se realizó una revisión de la literatura sobre estudios pertinentes publicados desde 2010, utilizando PubMed, Scopus y Web of Science entre 2019 y 2020. Los datos pertinentes fueron extraídos sistemáticamente de 61 artículos entre marzo y abril de 2021 Se realizaron y analizaron temáticamente entrevistas semiestructuradas con diez informantes clave, seleccionados por su experiencia aplicando intervenciones de autocuidado de la SSR. Las leyes y políticas y los derechos y el género no se están tratando sistemáticamente en la aplicación de intervenciones de autocuidado de la SSR. En cada país varía la atención prestada al entorno legislativo, que incluye la aceptabilidad de las intervenciones, privacidad, consentimiento informado y preocupaciones relativas al género, ya que estos afectan tanto la accesibilidad como el uso de intervenciones de autocuidado específicas, mientras que otras consideraciones jurídicas parecen haber sido subpriorizadas. Se necesita orientación operativa para formular y aplicar leyes y políticas solidarias, así como para garantizar la incorporación de las preocupaciones relativas a los derechos y al género en la aplicación de intervenciones de autocuidado de la SSR.

Introduction

The role of self-care interventions as an additional option to facility-based health services has been brought into particularly sharp relief in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic during which access to and delivery of health services has been disrupted around the world, leading to a prioritisation of self-care interventions across many areas of health.Citation1–3 Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, it is highly likely that self-care interventions, with links to supportive health systems, will continue to play important roles in people’s lives and in health service delivery.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined self-care interventions as evidence-based information, medicines, diagnostics, products and technologies that are fully or partially separate from formal health services and that can be used with or without a health worker.Citation4 Recognising the increasing use of self-care interventions, the WHO Guideline on Self-Care Interventions for Health and Well-being represents an important policy acknowledgment of a shift in healthcare delivery and an effort to support individuals and communities to optimise their health.Citation5

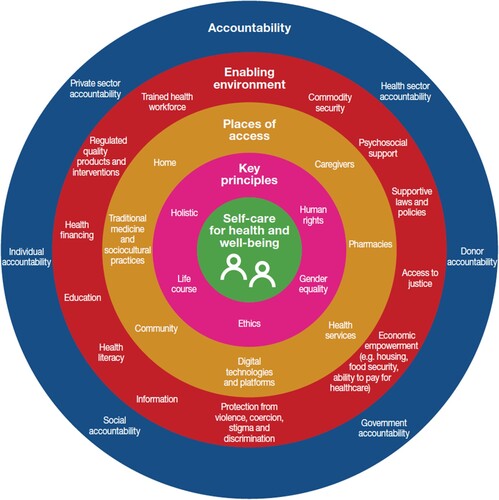

Beyond characteristics such as biomedical efficacy, simplicity of use, acceptability and cost-effectiveness that governments factor into considerations around the introduction and adoption of self-care interventions,Citation6,Citation7 there needs to be attention to the larger health eco-system within which people live and into which these interventions must fit.Citation8 (see ).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for self-care interventionsCitation69

This larger eco-system includes the laws and policies that impact health outcomes and access to justice, as well as attention to human rights and gender concerns across diverse contexts (see Enabling environment in ). Systematic consideration of laws and policies, human rights and gender has been found to support better health interventions,Citation9,Citation10 and given the increased importance of self-care interventions, there is an important opportunity to systematically address these issues in their introduction and scale-up.

Potential legal barriers to self-care interventions include laws that require third-party authorisation for accessing services, such as the need for consent of a parent for an adolescent to access over-the-counter emergency contraceptionCitation11 or HIV self-tests,Citation12 laws that criminalise sex between men or sex work, which might prevent people from adopting safer sex practices such as using condoms or HIV self-testing,Citation13,Citation14 or for women and gender-diverse individuals to self-manage medical abortion.Citation15 When underserved and marginalised individuals and communities face human rights violations or stigma and discrimination, for example due to their gender identity or expression, they may seek self-care options by default to avoid healthcare in facilities where they fear receiving sub-standard care.Citation16

Embedded within and across societies, organisations, systemic structures and institutional norms, gender is socially constructed.Citation17 It both influences and is influenced by “the distribution of power and resources, divisions of work and labour, distinctions between production and reproduction, and expectations and opportunities available … in all societies”.Citation18 Studies have shown that consideration of gender-related vulnerabilities in the design and implementation of self-care interventions, particularly for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), can help to promote their acceptability, correct and rational use, and safety.Citation6,Citation19 This might include, for example, designing interventions that affect women’s ability to access information, maintain privacy, or that help people avoid risk of gender-based violence.Citation20,Citation21 It might mean understanding the specific systemic barriers that women and girls and trans and gender-diverse people face to accessing health services, (e.g. health worker attitudes, a hostile legal environment) support and information, including for self-care interventions.Citation22,Citation23 It could also include exploring the potential for self-care interventions to reach men and boys who, through societal and gender norms, may be less likely to access formal health services,Citation24 or engaging understanding of gendered power dynamics that may shape men’s reaction to their partners’ and others’ use of self-care interventions.Citation25 The importance of gender as an influence over agency and as a potential barrier to access and use of self-care interventions for SRHR is often acknowledged,Citation26 but how best to address these concerns remains unclear (Box 1).

1. The right to the highest attainable standard of health is key to this analysis. For the user (the rights-holder), the ability to engage in self-care interventions that are available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality is key. For the duty-bearer (i.e. an actor, usually a State actor, who has an obligation to respect, protect and fulfil human rights), this should form the raison d’être of laws, policies and regulations governing self-care interventions.

2. Active and fully informed participation of individuals in how self-care interventions are implemented is critical, and supports other relevant rights including informed decision-making, privacy and confidentiality.

3. A focus on non-discrimination highlights the particular challenges faced by people who may be marginalised or face stigma or discrimination in access because of for example, their gender, age, race, sexual orientation, ethnicity, ability, gender identity, or some combination thereof. Discrimination may also arise from perceived engagement in certain behaviours such as sex work and drug use.

4. The right to seek, receive and impart information relates to how the provision of information is regulated, including where liability falls for inaccurate or false information. This becomes particularly important for self-care interventions where users must seek information themselves, often relying on publicly available information rather than health professionals to make appropriate self-care decisions.

5. People’s informed decision-making ability around self-care interventions is shaped by whether government actors, manufacturers, health workers or other duty-bearers facilitate such decision-making, including through non-discriminatory provision of information that is accurate, accessible, clear, and user-friendly.

6. Privacy and confidentiality are important for access, use and results of self-care interventions, as well as conditions for a range of other rights. Within formal healthcare, there generally exists some degree of adherence to medical and human rights standards of privacy and confidentiality. Where self-care interventions are accessed online or in other non-medical settings, such guarantees may require augmented consideration.

7. The human rights and legal dimensions of accountability in relation to self-care interventions encompass accountability of the health sector, the broader legal and policy environment, regulation of the private sector, and access to a system of redress. This includes ensuring that self-care interventions are made available as an adjunct to and with support from the health system, and not as an abdication of governmental responsibility for health care.

This article aims to use the current evidence base to examine the extent to which implementation of self-care interventions for SRHR has incorporated attention to laws and policies, human rights and gender, permitting a systematic analysis of the extent to which each is considered both alone and in combination, where gaps exist, and lessons that might help strengthen introduction and scale-up of self-care interventions for SRHR and other areas of health.

Methods

This review of attention to laws and policies, human rights and gender in literature relevant to self-care interventions for SRH published since 2010 was conducted using PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. Searches were carried out in December 2020. Drawing on substantive expertise and previous experience with relevant literature reviews, the research team identified relevant search terms. See Appendix for a sample search string. Search terms are outlined in ; Boolean “or” was used within columns one and two, Boolean “and” was used between all columns and within column three.

Table 1. Search terminology used in literature review

Articles were reviewed by three researchers using agreed upon inclusion criteria:

- Article describes a self-care intervention with clear outcomes;

- Article discusses legal, gender or rights issues associated with implementation or uptake of the intervention;

-Article published in English; and

- Article discussed a real-life scenario where implementation takes place (rather than a clinical trial or a conceptual approach).

Articles that met the inclusion criteria went through a data extraction process using key questions developed by the research team and applicable across diverse populations and geographies. These questions were used as column headings in our data extraction matrix, and we attempted to answer each one based on data available in the article (see Box 2). Data extraction was carried out in duplicate by two researchers to ensure completeness.

Research Questions: All with a focus on SRHR

1. What is the specific self-care intervention that was implemented?

2. What was the methodology/process for implementation/study design?

3. Which human rights are discussed?

4. How is gender considered/addressed in the study/intervention?

5. How does implementation including establishing an enabling legal, policy and regulatory environment come into play?

6. What connections/disconnects exist between the self-care intervention and the health system?

a. Are users choosing self-care interventions over health care systems as their entry point for care or is self-care in complement to accessing health care systems?

7. What setbacks or problems existed in implementation?

8. What successes were there in implementation?

9. What are key recommendations/considerations provided in the article?

Based on online searches, a review of grey literature published by select organisations working on self-care interventions for SRHR (International Planned Parenthood Federation, MSI Reproductive Choices, PATH and PSI) was also carried out using identical inclusion criteria and research questions for data extraction.

No formal quality assessment was carried out on either peer-reviewed article or grey literature reviewed.

To complement the ways law and policy, human rights and gender have been written up in peer-reviewed and grey literature as part of the implementation of self-care interventions and in an attempt to capture up-to-date information, key informant interviews were carried out between March and April 2021 via Zoom with a total of 10 implementers working on self-care interventions for SRHR: seven working with non-governmental organisations, two working at the World Health Organization and one independent consultant. Potential key informants were identified initially based on authorship of relevant publications and then snowball sampling was used to broaden the scope beyond “known” experts. All potential interview participants approached agreed to participate. Of these, five worked generally on SRHR self-care interventions, three worked specifically on self-injection of contraception, one worked on HIV self-testing, and one worked on the Caya diaphragm (a non-hormonal, barrier contraceptive). All interview participants were female. There was one participant from North Africa, one from West Africa and one from East Africa; the remaining seven were from North America. Participants were identified by reaching out to organisations known to be actively implementing self-care interventions for SRHR and asking staff who might be best positioned to help contextualise this work. Interview questions focused on the attention given to the legal and policy environment, human rights, and gender in their implementation experience, particularly probing to fill gaps in the literature (see supplementary file for the interview guide). Interviews were not recorded but detailed notes were taken. Within each of the three topical areas mentioned above, data relevant to the themes explored in the literature review was also extracted. Two researchers independently analysed and synthesised the data and reviewed findings jointly to come to agreement on salient themes and their meanings. Ethical approval was not sought as participants were answering only the generic questions listed from a professional perspective; information was provided to all participants on how data would be used and consent was sought prior to the interview.

Findings

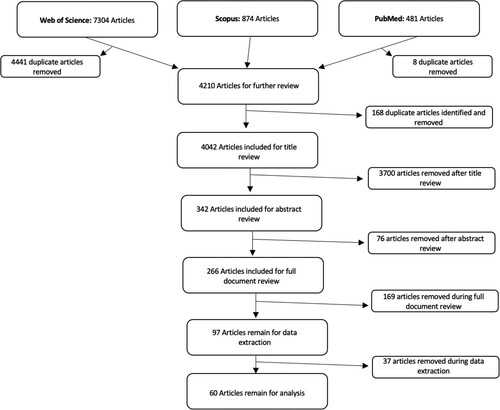

The literature searches identified 4042 unique articles; after stepwise title, abstract and full-text reviews, 60 articles were included in the analysis (see ).

The majority of articles covered HIV self-testing (n = 37) or self-management of medical abortion (n = 9); the remaining 14 articles covered a range of interventions including self-administration of injectable contraception, self-sampling for HPV and self-collection of samples for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). An overview of the articles included in the review is provided in Supplementary Table 1, organised by the type of self-care intervention being studied. A tendency towards inclusion in the earlier stages of the literature review meant that a relatively large number of articles were excluded at full text stage and during data extraction when it became apparent that even when looking at the detail of the article, there were no substantive lessons relating to human rights and gender.

Law and policies related to SRH were explicitly mentioned in 21 articles,Citation6,Citation7,Citation19,Citation22,Citation27–39,Citation44,Citation74,Citation75,Citation66 many of which discussed policies surrounding abortion and HIV testing restrictions.

Only four articles explicitly mentioned human rightsCitation28,Citation33,Citation40,Citation50 only one of which went beyond simply mentioning a right and actually provided detailed human rights analysis.Citation33 Many articles referenced principles that could be interpreted to be related to human rights, but lacked a systematic human rights framing. Across the literature, despite some attention to rights there is a striking lack of attention to participation and accountability, even as both are deemed important for use and uptake of self-care interventions.

Gender was referenced in 25 articles, however, 16 of these focused on women and did not consider how gender norms or standards affect men or gender-diverse people.Citation28–30,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation39,Citation41–48 Ten articles compared perceptions between men and women regarding self-care interventions.Citation6,Citation12,Citation19,Citation33,Citation37,Citation38,Citation49,Citation50,Citation51,Citation74 Eight articles studied self-care interventions among transgender populations.Citation20,Citation22,Citation52–57 The only articles focused exclusively on cisgender men were about men who have sex with men.Citation21,Citation23,Citation31,Citation36,Citation58,Citation59,Citation60–65

breaks down the articles by geographic spread and notes their inclusion of concepts relating to law and policy, human rights and gender. For each of the human rights principles included, this does not mean that the research was explicitly framed from a rights perspective, simply that rights concepts were in some way addressed. Rows in the table represent the regional spread represented among articles identified and columns highlight the number of articles that include attention and discussion to law and policy, human rights principles and gender.

Table 2: Breakdown of peer-reviewed literature by geography and attention to law and policy, human rights and gender

Articles reporting on projects in Africa, Europe and North America appear to have broadly studied human rights principles, while in Asia and Central and South America these principles are less frequently discussed. Gender, however, was addressed in both articles from South America, but much less across other regions.

The findings are organised into three sub-sections, each one a key piece of the enabling environment: legal and policy environment; human rights; and gender. Within each subsection, information is provided on how these factors have been considered in the implementation of self-care interventions for SRHR. Data from qualitative interviews are included, noting the type of respondent as well as their area of work. The importance of looking at law and policy, human rights and gender not only individually but together is brought out in the discussion.

Legal and policy environment

Across the literature reviewed, there is widespread acknowledgement of the importance of the legal and policy environment especially when new self-care interventions are introduced. Across the interviews, participants noted that the concept of an enabling environment was important for implementation efforts but how that was understood and operationalised varied. Attention to the importance of policy was universal, with widespread acknowledgment of the need for policies or regulations to ensure appropriate delivery of and access to self-care interventions for SRHR, even as there was very little mention of legal considerations for implementation. The section below first explores existing legal barriers, followed by efforts to remove such barriers. Then the policy response is explored and, finally, the importance of ensuring implementation of laws and policies is highlighted. Illustrative examples are provided.

Legal barriers

Laws and policies around abortion, including self-managed medical abortion, are known to be complex and often create insuperable barriers to access, particularly among underserved and marginalised groups.Citation27 Additional challenges for self-care may arise in the context of conflicting laws and policies, for example different legal ages of consent for sex than for accessing services,Citation19,Citation36,Citation38 highlighting the importance of attention to all relevant aspects of the broader legal and policy environment.

Removing legal barriers

To date, many countries appear to have focused primarily on documenting and consolidating existing laws, policies and practices for different self-care interventions to understand relevant gaps or barriers, with attention to legal advocacy evident only more recently (NGO representative, family planning). A key informant described the effort to change laws as an arduous and politically complex process and thus even as the legal environment is recognised to have important ramifications, these are often not sufficiently considered or addressed in the context of introducing or scaling up self-care interventions (NGO representative, family planning). In some cases, barriers impacting the use of self-care interventions include laws that are contentious, such as those that criminalise sex work or sex between men, which may impact willingness to access health services for fear of discrimination, further reducing the willingness of organisations working specifically on self-care interventions for SRHR to seek to change them.

Several examples of proactive government engagement in creating supportive legal frameworks came up through this review process. A key informant described that in some places, including Egypt and Morocco, parliamentarians have been eager to be involved and help create a conducive framework for self-care interventions; in both cases, the Ministry of Health played a key role providing technical information and data to support necessary legal and policy change. (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR) In the UK, government revocation, in 2014, of regulations that prevented the promotion and sale of HIV self-tests allowed for the introduction of HIV self-testing interventions.Citation61

New policies

Policies are recognised as a critical lever for supporting self-care interventions. Most often mentioned in the literature are policies recently passed surrounding specific self-care interventions,Citation7,Citation22,Citation31,Citation37,Citation38,Citation66 as well as those that serve as barriers to self-care implementation.Citation19,Citation27,Citation29,Citation33–36,Citation39,Citation44,Citation45

Just as some countries have been proactive in creating supportive laws relating to self-care interventions for SRHR, the same is true for policies. In Burkina Faso, for example, the importance of multisectoral dialogues to shift policy has been highlighted, involving not just the Ministry of Health but also the Ministries of Women, Education, Justice and Social Services.Citation67 (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR) In Malawi, the introduction of a relevant policy framework for sub-cutaneous self-injectable Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-SC) came at a time when large, randomised trials showed high continuation rates and, simultaneously, there were substantial stock-outs of intramuscular DMPA. This highlighted the need for alternative contraceptive options, which was the impetus for the policy change to allow for the introduction of DMPA-SC. (NGO representative, family planning).

Adjusting existing policies

The introduction of self-care interventions may also require policy changes to change or expand the cadres of health workers (including community health workers) allowed to administer or support certain interventions.Citation68,Citation69 It was noted this has been particularly evident where self-administration of self-injectable contraception has been introduced, and a concerted effort to ensure policy change to facilitate task sharing has often been required (Independent consultant, self-care interventions for SRHR).

Implementation of laws and policies

While laws and policies that are supportive of non-discriminatory access to self-care interventions are critical, this is not sufficient and to ensure their impact they must be fully implemented.Citation69 For example, of the nearly 81% of countries that have cervical cancer policies or strategies many of which include self-sampling for HPV, only 48% have an operational plan with funding, which limits their potential impact.Citation39 In the context of HIV self-testing, in mid-2019, 77 countries had supportive policies in place but only 38 had actually made HIV self-testing available.Citation66 Even where policies support regular HIV self-testing, few places have the capacity to actually do this.Citation36 One study described the positive evolution of the SRH-related legal framework in Argentina, noting however that additional guidance and action are still needed for the potential benefits of these laws to be fulfilled.Citation22 Kenya also has in place a robust policy framework for self-administration of injectable contraception and yet this intervention is not yet widely available.Citation70,Citation71 The Ministry of Health is often well situated to create policy-level guidance or recommendations but translating this into practical guidance for health facilities requires additional effort (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR).

Human rights

Similar to the legal and policy environment, human rights are often noted as important in implementation of self-care interventions, however most articles reviewed did not explicitly discuss rights in the context of their work. Attention to human rights is often much more implicit: “The policy attention is there to reaching different segments of the population but it’s not framed around rights or equity, nor is it systematic” (NGO representative, family planning).

While some human rights issues, even if not framed as such, appear to have been given a lot of consideration in the implementation efforts reviewed, particularly around such issues as acceptability and informed decision-making, no implementation effort was described as explicitly using a human rights framework or systematically considering all key human rights and principles.

Key informants described a lack of clarity around how to operationalise rights in this context. Discussion of individual human rights concepts such as participation, access to information and informed decision-making was more frequent even if not framed as rights issues per se (NGO representative, family planning).

Below, both explicit and implicit attention to each of the human rights principles described in Box 1 is analysed in turn.Citation72 These issues were generally not explicitly framed as human rights either in the published literature or in how key informants described their work. Where possible, we highlight similarities and differences in attention to rights across different self-care interventions.

Right to health

None of the articles reviewed explicitly mentioned the right to health. However, the principles of availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of health facilities, goods and services were mentioned to differing degrees in regard to different self-care interventions in the literature and interviews, even if often not explicitly stated as being from a rights perspective ().

Availability

Availability of self-care interventions for SRHR was not explicitly discussed in the literature reviewed. However, key informants described the persistent challenges in securing the availability of relevant commodities, particularly where the number of product suppliers is limited (Independent consultant, self-care interventions for SRHR; WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR).

Accessibility

Across the literature reviewed, accessibility was discussed as a persisting challenge, including as concerns any required linkages with the health system. For instance, it was noted that access to a self-administered injectable contraception requires a prescription and a health worker to demonstrate how to self-inject.Citation42,Citation43 In many low- and middle-income settings, as access to facility-based services is low, access to self-care interventions is also low. For example, limited geographic access to care due to limited available transportation to obtain commodities was described as a barrier for HIV self-testing across regions.Citation22,Citation31,Citation38,Citation54,Citation57,Citation59,Citation73–76 In many settings, HIV self-testing was considered a way to increase the number of people getting tested and the frequency of testing for HIV. However the resulting lack of access to counselling was frequently discussed as an issue needing to be addressed in implementation, particularly where self-testing results were received at home.Citation21,Citation23,Citation36,Citation37,Citation50,Citation53,Citation54,Citation60,Citation62,Citation63,Citation65,Citation76–80

An interview participant noted the difference in rolling out a potentially “one-time” intervention and one that requires ongoing engagement with the health system. HIV self-testing can, in some settings, be made easily available online and, in the case of a negative test result, may not require additional follow-up, whereas pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV (PrEP) requires repeat engagements, which may be more challenging but might also increase access to other services:

“Self-care interventions that require ongoing engagement provide an ability to extend the reach of services beyond currently reached groups and get into layers of people who don’t have access to services … PrEP is more focused on empowerment and health-seeking behavior, self-efficacy … it opens the door to access other services even beyond HIV.” (NGO representative, HIV)

A study in the UK noted that for the online offer of STI self-sampling, integration of online services with face-to-face clinical pathways was key to ensuring the accessibility of follow-up care.Citation81 To minimise loss to follow-up, a US-based programme for college students provided appointment-free STI self-screening within a health facility, with the possibility of seeing a clinician immediately post-test if required.Citation49

With respect to self-managed medical abortion, in addition to lack of access due to geographic distance, limited numbers of health facilities and limited access to quality services were also discussed as relevant barriers.Citation33 Additional barriers reported included difficulty taking time away from work, finding childcare to access the required services and inability to attend the clinic because of lack of partner support.Citation27–30,Citation32–35,Citation44

Across all types of self-care interventions for SRHR, affordability was seen as a barrier to access, including both costs of transportation to access the intervention – whether at a health facility or pharmacy – and any costs associated with the intervention itself such as buying an HIV self-test kit or abortion medications.Citation7,Citation28,Citation29,Citation54,Citation66,Citation74,Citation76

In some settings, self-care interventions were provided at no costCitation41,Citation58 (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR) but this approach was deemed unsustainable. In many cases, a key informant observed, there has been a shift in cost burden from the health system to the user, particularly where self-care interventions are accessed outside health facilities (Independent consultant, self-care interventions for SRHR). Specific to HIV self-testing, studies in both high- and low-income settings have found it can be a cost-effective strategy for the health system, but these studies did not also assess users’ out-of-pocket expenditures or perspectives.Citation19,Citation36,Citation50,Citation62,Citation63,Citation82

Acceptability

Even if not explicitly from a rights perspective, a lot of work has been carried out on the acceptability of self-care interventions for SRHR. Many publications focus on assessing acceptability of a single intervention for a specific target community, including information on preferred points of access, confidence using the intervention and types of support preferred.

Across locations and populations, the acceptability of HIV self-testing, for example, was often found to be higher than facility-based testing.Citation6,Citation7,Citation19,Citation37,Citation38,Citation52,Citation54,Citation62,Citation64,Citation74,Citation80,Citation83,Citation84 In the UK, HIV self-testing was seen as more convenient and more confidential in some communities due to immediate results, less blood required in self-sampling, ability to complete tests alone and the privacy it offers.Citation77 In Puerto Rico and New York City, men who have sex with men and transgender women reported feeling comfortable and able to talk to their partners about HIV self-testing, with many casual sexual partners agreeing to self-test.Citation55 A key informant described that, in Vietnam, because of the interest and demand from men who have sex with men, transgender women, female sex workers, and people who inject drugs and their sex partners, there has been a lot of work to understand client preferences on where, from whom and how to receive HIV self-testing (NGO representative, HIV).

Telemedicine services for abortion-related care were described as safe, efficacious, acceptable and, for many women, preferable to clinic settings because of comfort, privacy and convenience.Citation27,Citation28,Citation34 Many women reported that they would recommend self-managed medical abortion to others.Citation34

Through interviews with clients in Senegal, one study found self-injectable contraception to be feasible and acceptable.Citation43 Further, a key informant noted that, in Uganda, girls in boarding school found the accessibility of self-injectable contraception acceptable as it affords a discreet way to access contraception at home and then use it while in school. (NGO representative, family planning) Three articles included implicit attention to the acceptability of self-sampling for HPV as a successful method for screening for cervical cancer, two focusing on how this provides an alternative to invasive pelvic exams and the other highlighting the additional benefit of reduced risk of exposure during the COVID-19 pandemic for both clients and health workers.Citation45,Citation47,Citation58 A systematic review and meta-analysis of self-collection of samples as an additional approach to deliver testing services for STIs found very high levels of acceptability across studies, all of which were in high-income settings.Citation51

Quality

Across the literature reviewed, quality was not explicitly discussed as a rights issue, but 13 articles discussed quality of care and services.Citation23,Citation33,Citation34,Citation39,Citation40,Citation44–46,Citation49–51,Citation65,Citation74 and one article covered quality of life more broadlyCitation66 While quality is discussed, it is only mentioned briefly and without substantial detail.

Some studies looking at the introduction of a new self-care intervention, have focused on trying to ensure the quality of information and client training, using client feedback to improve quality of delivery and messaging.Citation85,Citation86 Key to ensuring quality is that health workers must have training to promote self-care interventions, show clients how to use such interventions and be available for any counselling or support as needed.Citation8,Citation69 However, a key informant noted that shortages and maldistribution of health workers can mean that, even among those who are engaged, they are often unable to incorporate additional tasks into their work (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR).

Participation

Participation was not framed from a rights perspective in most of the literature reviewed. While participation can be understood to be about client-health worker interactions, it also encompasses the notion of engagement of all stakeholders, including communities, in the development of self-care interventions, i.e. how they should be implemented in any given community.Citation33 A key informant said that consultation with users, civil society, UN partners, government agencies and others was routine in implementation of all self-care interventions to help ensure shared ownership and acceptability (NGO representative, family planning). The Caya diaphragm intervention in Niger engaged the participation of a range of stakeholders including the Ministry of Health, local leaders, district health officials, religious leaders, community health workers, professional associations, local pharmacies and community members, all of which helped facilitate product introduction.Citation85,Citation86 In Uganda, human-centred design was key to development of an intervention to implement self-injectable contraception, with health workers and potential users engaged from the outset (Independent consultant, self-care interventions for SRHR).

Non-discrimination

Discrimination, as well as stigma, were key issues discussed across the literature with key informants providing additional detail about work being done to address them. Many researchers stated that their self-care interventions were designed to reduce stigma and discrimination surrounding specific health services such as HIV and abortion services. Across different settings, high-risk urban populations, students aged 15–24, and men who have sex with men, each reported having avoided facility-based care due to fear of stigma and discrimination.Citation23,Citation50,Citation73,Citation82 Self-care interventions allowed for greater uptake, and were often preferred, among study populations in need of HIV- and abortion-related services.Citation22,Citation35,Citation52,Citation77

The principle of non-discrimination requires making additional efforts to reach populations with low access to health services.Citation87 Key informants described how work is currently being done to meet with hard-to-reach communities who face discrimination, including those of very low socioeconomic status, women with disabilities and people in humanitarian contexts, to understand if and how self-care interventions for SRHR might better respond to their needs (WHO representatives, self-care interventions for SRHR). However, due to funding constraints, it was not always possible to carry out the types of assessments needed to understand which populations are hardest to reach, why and what can be done to support them:

“We’d like to do an assessment segmenting the population groups we’re trying to reach to understand preferences, needs, barriers and so on. But it’s often hard to fund, especially given the targets we need to hit. So we haven’t done it a lot. If we can, we do it.” (NGO representative, family planning)

Right to information

Across the literature reviewed, even if information was not discussed as a right, providing clients with necessary information was often presented as essential. Even when clients complain about health workers’ attitudes, they still largely trust the information they provide so the quality of health worker training to ensure clients gain information necessary to perform self-care interventions is an important consideration.Citation28,Citation50,Citation78 (NGO representative, family planning) A key informant noted that the education level of clients has been found to be a factor for whether clients feel comfortable with the level of information or training they receive for a particular self-care intervention (NGO representative, family planning). Education level may influence women’s sense of self-efficacy to use self-care interventions, including self-sampling for HPV, with women with higher literacy more likely to choose self-sampling.Citation46 Thus, even when self-care interventions are accessible, lower education levels may result in higher information and support requirements. The COVID-19 pandemic particularly brought attention to the importance of information to ensure clients can perform self-care safely and appropriately while also keeping clients and health workers safe in the process.Citation58 Echoing the literature reviewed, interview participants highlighted the importance of women’s education and literacy for promoting access to information, recognising that challenges remain in this area (Independent consultant, self-care interventions for SRHR; WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR; NGO representative, family planning).

A wide range of communication channels have been used to provide information about self-care interventions for SRHR to different populations. This can include broad use of traditional media like radio and print media as well as SMS, Facebook messenger and other online platforms (NGO representative, family planning). Another key informant described how in Morocco, Lebanon and Pakistan, information has been provided via public health centres and NGOs, as well as through a standardised app that provides information on how and when to use self-care interventions, allowing users to make the choice if they want to do so or not (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR).

Right to informed decision-making

While many articles discussed training of health workers to deliver information to populations who might use self-care interventions, none directly linked this to clients’ right to informed decision-making. However, the concept of informed decision-making was central to how interventions across a range of self-care interventions were carried out, with implementers striving to ensure that appropriate information was provided to clients.Citation28,Citation33,Citation42,Citation43,Citation50,Citation56,Citation58,Citation78,Citation88 Given the diversity of self-care interventions, the importance of ensuring that information be provided to promote informed decision-making, appropriately tailored by intervention, and provided along with the acknowledgement that self-care interventions may not be for everyone was noted (NGO representative, family planning).

Privacy and confidentiality

Across the range of articles reviewed, privacy and confidentiality were discussed as key considerations in the implementation of all self-care interventions for SRHR, sometimes in the context of potentially stigmatised issues such as HIV or abortion, sometimes in relation to maintaining secrecy from a partner, family or community, and sometimes more generally about the potential privacy that self-care interventions can provide.

While HIV self-testing, for example, may help to reduce stigma, one clear lesson is that testing at home does not automatically ensure privacy,Citation40,Citation76 demonstrating that additional considerations are needed. In the context of HIV self-testing, the need was noted to also ensure private environments in clinics when conducting such tests,Citation22,Citation62,Citation65 as well as at test distribution points such as pharmacies.Citation74 In a study in the UK, HIV self-testing was provided through digital vending machines as a deliberate strategy to reduce stigma because of its relative privacy.Citation60 This innovative method of delivery was deemed feasible and acceptable. However, the need for health workers to ensure adequate access to information and linkage to services was also noted.Citation60

Accountability

Accountability, which encompasses legal, political, institutional and social accountability among others, was not explicitly discussed in any of the literature reviewed. A key informant noted that with many self-care interventions being made available at corner stores or online, ensuring accountability for the quality of products can be a challenge (Independent consultant, self-care interventions for SRHR). This raises questions around which indicators can provide the necessary information to promote accountability (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR). Robust monitoring and evaluation systems are required that link to national health management information systems and provide for client follow-up as appropriate (WHO representative, self-care interventions for SRHR).

Gender

The need to understand how gender roles might restrict women’s ability to use self-care interventions for SRHR and the importance of male involvement was noted in the literature reviewed, but deeper analysis of local constructions of gender was often missing. Interview participants provided useful insights into how gender is (and is not) being considered in introducing self-care interventions, including for women, men, transgender or gender-diverse populations. Despite initial hopes that self-care interventions would empower women, the reality reported is that there have been challenges to using self-care interventions in the home and many women, particularly female adolescents, report that their use of self-care interventions is done in secret:

“Adolescents are a population of high interest for self-injection [of contraception] because it’s more discrete, but it depends on her situation. She might not be able to get the product from a health worker or community health worker because she might get a morality lesson instead of contraception. If she can get it, and has privacy, it can be more discreet”. (NGO representative, family planning)

Rather than going as far as seeking to transform gender norms, it was hoped that this type of intervention might simply in the first instance help circumvent barriers to access relating to gender.

In this context, safety relies on privacy. There are additional opportunities for innovation where self-care interventions are used: women around the world congregate in women-only spaces – markets, water points, women’s groups – where they can provide substantial mutual support. With greater attention to gender in planning self-care interventions, these might be used as safe spaces for access (NGO representative, family planning).

Some stakeholders pinned a lot of hopes on self-injectable contraception as useful for women and girls who may not be accessing health services such as girls in child marriages or women who require their husband’s permission to leave the house. Yet, gender-related challenges cannot be simply undone by the introduction of new biomedical technology, however safe, effective and acceptable these technologies may be. Even if women can access self-injectable contraception, which nonetheless requires access to health services, challenges remain with regard to information, storing and disposing of the units, over and above privacy for self-injection (NGO representative, family planning).

In parts of West Africa, discussions with men, including local and religious leaders, were seen as important given their decision-making power. When this was done during introduction of the Caya diaphragm, for example, it resulted in some men being supportive of their wives using the product (NGO representative, family planning), even as it did not address underlying gender inequalities.

A few of the articles reviewed raised issues around power dynamics between sexual partners. In the context of HIV self-testing for example, one study noted that women are still often considered the ones responsible for prevention, screening and disclosure of serological status to their partner.Citation38 Two studies found evidence of partners not allowing collection of specimens for HPV self-sampling,Citation48 and several articles on self-managed medical abortion discussed women’s fear of negative consequences or opposition from their partner.Citation28,Citation33,Citation35

In the peer-reviewed literature, there is attention to different levels of acceptability of some self-care interventions among women, men and transgender populations, different preferred points of access and different motivations in accessing self-care interventions underlying these preferences, which is undoubtedly useful information for planning interventions and service delivery. One study, for example, found that more women than men felt it important to have in-person one-on-one counselling at the time of HIV testing,Citation50 while another study attributed men’s preference for home-based HIV self-testing over facility-based HIV testing services to persisting challenges in accessing health facilities including inconvenient opening hours and distance to facilities.Citation19 A systematic review found that transgender people preferred mail delivery of HIV self-tests to accessing them from a health facility.Citation66 However, in-depth analysis of constructions of gender as they affect the potential effectiveness of self-care interventions, which is also key for informing interventions and service delivery, is rare.

A key informant suggested that gender is seen more as an issue to be addressed in programming than policy (NGO representative, family planning), but without specific attention to gender in policy, systematic attention at the programmatic level is unlikely.

Discussion

This review focuses on the extent to which implementation of self-care interventions for SRHR has included attention to law and policy, human rights and gender. In so doing, we have highlighted certain components within these areas that have received some attention and others where there has been little to no focus to date. While we did not set out to explore what this might mean for health systems, as has been previously noted, it became very clear that health system strengthening is a critical corollary to creating safe and supportive enabling environments for effective introduction and uptake of self-care interventions.Citation68,Citation69,Citation89

In this section, we provide an overview of the importance of context-specificity in self-care interventions and explore the implications of our findings – bringing together the findings across law and policy, human rights and gender – for work to improve health systems and enabling environments.

Context specificity

Some implementation considerations cut across different self-care interventions, but others are intervention-specific, requiring careful planning. The same intervention designed for different populations might have to look quite different, with structural, cultural, gender-related and legal factors impacting groups and individuals differently. While this may be true for all health services, the fact that self-care interventions are often used outside the healthcare setting increases the salience of these issues. For example, how best DMPA-SC might be provided may depend on whether or not CHWs are allowed to administer it. The reach of the internet and confidence in online shopping can affect distribution channels for self-care interventions, with most interventions in this review that relied on the internet carried out in high-income settings.

Beyond understanding the traditional barriers to accessing health services, it is crucial to understand the lived realities of intended beneficiaries to ensure that interventions can be appropriately designed for people to be able to and want to access them and use them safely. Implementation efforts will therefore always require additional analysis of vulnerabilities, support systems, power dynamics and constructions of gender even if these issues are well covered in policy documents.

Implications for creating an enabling environment

While at the global level, a lot of attention to self-care interventions has focused on technological innovation and product development, at the national level, key stakeholders rightly appear concerned with the practicalities of creating enabling environments appropriate to their context. National stakeholders are, however, often unsure about how best to do this. While global, and in some cases national, guidance exists on self-care interventions for SRHR, key informants noted a need for additional practical support on how to incorporate attention to law and policy, human rights and gender. Despite their importance, they have not been central to implementation of self-care interventions for SRHR to date.

Rather than each implementer focusing on introducing or providing a single self-care intervention, as is often the case in research and implementation, examining and understanding the broader range of self-care interventions might help better meet users’ needs. Furthermore, it might help expand important implementation considerations that go beyond an efficacious technology to address common concerns with the broader enabling environment.

Failure to systematically understand how law and policy, human rights and gender shape the environment within which self-care interventions are implemented, as well as how these interventions should be designed to ensure they are rights-based and gender-responsive, may limit the potential impact of self-care interventions for SRHR. Without understanding, for example, how gender norms might limit uptake of a self-care intervention in a given context, implementation efforts may be stymied. This review has highlighted the extent to which existing self-care interventions address these issues with a view to drawing attention to gaps that, with specific attention, could be closed. The evidence base remains thin on how best to promote, ensure and monitor the accessibility and quality of and accountability for self-care interventions as well as how self-care interventions might be gender transformative. Accountability is particularly critical in the context of self-care interventions given the complex range of issues that it raises including, for example, who should be held accountable for the quality of self-care interventions, self-care interventions administered outside the context of a health facility, and what accountability mechanisms (should) exist through which people can seek redress. Investigation is needed into how best different types of accountability might be fostered in this context.

The legal environment can have a direct impact on the implementation of self-care interventions. Legal and policy advocacy may be necessary to help remove legal barriers, yet this has often been seen to be outside the scope of self-care interventions. A review of self-administration of injectable contraception, over-the-counter oral contraception and self-management of medical abortion in the Eastern Mediterranean region highlighted the advantage of introducing regulatory changes to support increased access, availability and usage of essential self-care interventions for SRHR.Citation90 Furthermore, public sector ownership in advocating for better national policies has been shown to be effective in enabling introduction of misoprostol and self-injectable contraception in Pakistan.Citation91 The published literature on self-managed medical abortion and, to a lesser extent HIV self-testing, often includes in-depth analysis of law and policy as well as more explicit reference to human rights than other types of self-care interventions for SRHR in the literature reviewed; and this may be an area from which people implementing other self-care interventions can draw. Learning how to assimilate lessons learned from the provision of one type of self-care intervention for SRHR to another would be useful also for strengthening linkages across SRH and with other health services.

While the legal environment, rights and gender are important in the context of facility-based SRH service provision, each takes on additional dimensions in the context of self-care interventions accessed and used in the community or at home. Societal values, home environments, community and familial relationships, social support and safe spaces all take on increasing importance and must therefore be considered in intervention design. Potential concerns around safety, confidentiality and coercion in the use of self-care interventions for SRHR are as yet under-studied.

Societal-level factors, including stigma, constructions of gender and traditional beliefs can, in some places, continue to create barriers to making self-care interventions for SRHR, even if they are available, useful for all populations.

Implications for the health system

Self-care interventions were initially envisaged by many as a pathway to reach beyond health systems, and while this can sometimes be the case, it is not always so. Across many of the interventions reviewed, the health system entry point remains key to success. While this may be key to initiation of the intervention, people often want to maintain a connection with the health system even if they are able to use the intervention in private. The linkage to the health care system plays out in many ways across geographies and cultural contexts and remains crucial for most self-care interventions. This means that, in many settings, the inclusion of self-care interventions might require more investment in the health system, particularly at the outset. In many of the studies reviewed, facility-based health workers were critical to supporting self-care interventions, including providing appropriate support for informed decision-making, counselling, building capacity for their use and following up with clients as needed.Citation36,Citation42,Citation43,Citation80

Despite assumptions that many people would like a way to remove health workers as gate-keepers to care, it appears many clients may not want the gate-keeper role of health workers removed (NGO representative, family planning). Rather, they seek a more supportive health care environment in which health workers have the competencies to promote and demonstrate the use of appropriate interventions, including self-care interventions. Whether self-care interventions should be delivered with or without the support of a health worker likely varies by intervention and setting. Self-injectable contraception, for example, can be self-administered but can equally be administered by a community health worker or a facility-based worker. Different models have been implemented across countries.Citation27–30,Citation32,Citation44 For self-care interventions that may be used frequently or over a long period of time, a continuum of support is needed to maintain informed decision-making and ensure access to laboratory assessments as required. Different models for providing this support – including through peers, community and facility-based health workers, and pharmacies – could usefully be studied in diverse settings.

Given how critical linkage to health services and health workers is for effective uptake of self-care interventions, a strong health system into which they can be integrated or layered is critical. Supportive laws, policies, regulations and guidelines are needed, as is their implementation including translation into operational tools, competency-based training, including on gender-responsive and rights-based care, and supportive supervision to enable health workers to implement them. Within the health system, basic infrastructure, electricity, water, internet, a regular supply of drugs and equipment, functional health information systems and an adequate workforce are all foundational to the success of self-care interventions. Across the Eastern Mediterranean region, which has been a trailblazer region in promoting and introducing self-care interventions for SRHR through the health system, this approach has accelerated positive health impacts through sustainable action at the local level driven by the health needs of people.Citation89

Limitations

Many examples of introduction and scale-up of self-care interventions for SRHR are not written up in either peer-reviewed or grey literature. Likewise, as noted above there is limited explicit attention to law, human rights and gender in what has been published; it is unclear whether this is due to bias in what journals are interested in publishing or if there is a true lack of attention to these issues in implementation and research. Only English-language articles were reviewed, excluding potentially useful lessons particularly from Latin America. In addition, this is a fast-moving field so there is always a delay between action and publication, and COVID-19 has sometimes also delayed publication. We tried to address these shortcomings by interviewing some known implementers in the field but comprehensive insight into the work being done is still needed.

Moving forward

Law and policy, human rights and gender are not being systematically addressed in the implementation of self-care interventions for SRHR. Resources such as the WHO normative guideline provide an opportunity to ensure these considerations are included in efforts for introduction and scale-up. Further guidance is needed to move toward the “how to” implement, drawing on the many national-level examples already available. The WHO SRHR policy portalFootnote* for self-care interventions provides a useful platform where these resources can be accessed, and thereby help inform such future guidance.

While the specifics might look different by location, this review draws attention to a range of issues that require deep consideration in designing and implementing self-care interventions, all of which in turn may help inform context-specific operational guidance.

As with other areas of health, published measures of success have largely been focused on the number of self-care interventions introduced at national level. A shift in how we measure success is needed to also capture, for all populations, the availability of appropriate interventions, the satisfaction of interventions being utilised, how clients are learning about self-care interventions, whether or not clients were able to access training and information regarding the intervention of choice, and if they could access the intervention where they wanted and when they wanted. Guidance on monitoring and evaluation, including attention to assessing issues such as these, with sufficient attention to legal, human rights and gender considerations, could help provide a clearer picture of the overarching enabling environment required for implementing self-care interventions and thereby help promote equity, access and increased health coverage. While this is arguably important across all areas of health, with self-care interventions being used within homes and communities where there may be less regulated access to information and support, they feel particularly urgent in this context.

Critically, additional research is needed to fill current knowledge gaps regarding how best attention to law and policy, human rights and gender, can support effective introduction and uptake of self-care interventions. Important questions relating to the overarching enabling environment include the differential access to information and services among different populations, the willingness and ability to purchase self-care interventions online, mechanisms to ensure privacy in the delivery and use of self-care interventions, and how to ensure non-coercive use of self-care interventions. Implementation research in which the entire self-care ecosystem is analysed and addressed rather than focusing on the delivery of a single self-care intervention to a specific population will also be useful, as will attention to how to improve community involvement.

If appropriately designed, regulated and implemented, self-care interventions for SRHR expand choice and options of where, when and how to access certain health interventions. Ultimately, with appropriate attention to the enabling environment and health system, this can improve health and quality of life of people around the world, and contribute to the achievement of Universal Health Coverage.

Supplemental table 1. Overview of articles included in the review.

Download MS Word (50.1 KB)Key Informant Interview Guide

Download MS Word (31.7 KB)Disclosure statement

The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the World Health Organization (WHO) or the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP). All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Perera N, Agboola S. Are formal self-care interventions for healthy people effective? A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4:e001415.

- Riegel B, Dunbar SB, Fitzsimons D, et al. Self-care research: where are we now? Where are we going? Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;116:103402.

- WHO. Maintaining essential health services. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-essential-health-services-2020.1

- WHO. Self-care interventions for health. 2021a. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/self-care#tab = tab_1

- WHO. Self-care health interventions. 2021c. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/self-care-health-interventions

- Pintye J, Drake AL, Begnel E, et al. Acceptability and outcomes of distributing HIV self-tests for male partner testing in Kenyan maternal and child health and family planning clinics. Aids. 2019;33(8):1369–1378. doi:10.1097/qad.0000000000002211

- Zanolini A, Chipungu J, Vinikoor MJ, et al. HIV Self-testing in Lusaka province, Zambia: acceptability, comprehension of testing instructions, and individual preferences for self-test kit distribution in a population-based sample of adolescents and adults. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2018;34(3):254–260. doi:10.1089/aid.2017.0156

- Narasimhan M, Allotey P, Hardon A. Self care interventions to advance health and wellbeing: a conceptual framework to inform normative guidance. Br Med J. 2019;365:l688, doi:10.1136/bmj.l688

- Global Fund. HIV & AIDS. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. 2020. Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/hivaids/

- Gruskin S, Mills EJ, Tarantola D. History, principles, and practice of health and human rights. Lancet. 2007;370(9585):449–455.

- Savage-Oyekunle OA, Nienaber A. Adolescents’ access to emergency contraception in Africa: an empty promise? Afr Human Rights Law J. 2017;17(2):475–526. doi:10.17159/1996-2096/2017/v17n2a7

- Tonen-Wolyec S, Mbopi-Kéou FX, Koyalta D, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus self-testing in adolescents living in Sub-saharan Africa: an advocacy. Niger Med J: J Niger Medi Assoc. 2019a;60(4):165–168. doi:10.4103/nmj.NMJ_75_19

- Platt L, Grenfell P, Meiksin R, et al. Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2018;15(12):e1002680, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002680

- Santos GM, Makofane K, Arreola S, et al. Reductions in access to HIV prevention and care services are associated with arrest and convictions in a global survey of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;93(1):62–64. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2015-052386

- Donovan MK. Self-managed medication abortion: expanding the available options for U.S. Abortion Care. Guttmacher Institute. 2018. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2018/10/self-managed-medication-abortion-expanding-available-options-us-abortion-care

- WHO. Meeting on ethical, legal, human rights and social accountability implications of self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health: summary report. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-18-30

- Hawkes S, Buse K. The politics of gender and global health. In: McInnes C, Lee K, Youde J, editors. The Oxford handbook of global health politics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2020. p. 237–264.

- Hawkes S, Allotey P, Elhadj AS, et al. The lancet commission on gender and global health. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):521–522.

- Tonen-Wolyec S, Mboumba Bouassa RS, Batina-Agasa S, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents preferring home-based HIV self-testing over facility-based voluntary counseling and testing: a cross-sectional study in Kisangani, democratic republic of the Congo. Int J STD AIDS. 2020b;31(5):481–487. doi:10.1177/0956462419898616

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Giguere R, Balán IC, et al. Few aggressive or violent incidents are associated with the use of HIV self-tests to screen sexual partners among key populations. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2220–2226.

- Wesolowski L, Chavez P, Sullivan P, et al. Distribution of HIV self-tests by HIV-positive men who have sex with men to social and sexual contacts. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(4):893–899. doi:10.1007/s10461-018-2277-0

- Frola CE, Zalazar V, Cardozo N, et al. Home-based HIV testing: using different strategies among transgender women in Argentina. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0230429, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230429

- Zhao Y, Zhu X, Pérez AE, et al. MHealth approach to promote oral HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men in China: a qualitative description. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1146, doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6046-9

- Narasimhan M, Logie CH, Moody K, et al. The role of self-care interventions on men’s health-seeking behaviours to advance their sexual and reproductive health and rights. Health Res Policy Sys. 2021a;19:23, doi:10.1186/s12961-020-00655-0

- WHO. WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health: sexual and reproductive health and rights. 2019. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325480/9789241550550-eng.pdf

- PATH. Women’s self-care: products and practices. 2017. Available from: https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/RH_Outlook_Nov_2017.pdf

- Aiken ARA, Starling JE, Gomperts R, et al. Demand for self-managed online telemedicine abortion in the United States during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2020a;136(4):835–837. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004081

- Aiken ARA, Starling JE, van der Wal A, et al. Demand for self-managed medication abortion through an online telemedicine service in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2020b;110(1):90–97. doi:10.2105/ajph.2019.305369

- Aiken ARA, Broussard K, Johnson DM, et al. Knowledge, interest, and motivations surrounding self-managed medication abortion among patients at three Texas clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020c;223(2):e231–238.e210. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.026.

- Berry-Bibee EN, St Jean CJ, Nickerson NM, et al. (2018). Self-managed abortion in urban Haiti: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. doi:10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-200009

- Fan S, Liu Z, Luo Z, et al. Effect of availability of HIV self-testing on HIV testing frequency among men who have sex with men attending university in China (UniTest): protocol of a stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):149, doi:10.1186/s12879-020-4807-4

- Fuentes L, Baum S, Keefe-Oates B, et al. Texas women’s decisions and experiences regarding self-managed abortion. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):6, doi:10.1186/s12905-019-0877-0

- Hobday K, Zwi AB, Homer C, et al. Misoprostol for the prevention of post-partum haemorrhage in Mozambique: an analysis of the interface between human rights, maternal health and development. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2020;20(1):9, doi:10.1186/s12914-020-00229-9

- Moseson H, Bullard KA, Cisternas C, et al. Effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion between 13 and 24 weeks gestation: a retrospective review of case records from accompaniment groups in Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador. Contraception. 2020a;102(2):91–98. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.015

- Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, et al. Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020b;63:87–110. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.08.002

- Paschen-Wolff MM, Restar A, Gandhi AD, et al. A systematic review of interventions that promote frequent HIV testing. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(4):860–874. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02414-x

- Pasipamire L, Nesbitt RC, Dube L, et al. Implementation of community and facility-based HIV self-testing under routine conditions in southern Eswatini. Trop Med Int Health. 2020;25(6):723–731. doi:10.1111/tmi.13396

- Tonen-Wolyec S, Koyalta D, Mboumba Bouassa RS, et al. HIV self-testing in adolescents living in Sub-Saharan Africa. Med Mal Infect. 2020a;50(8):648–651. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2020.07.007

- Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, de Vuyst H, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001351, doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001351

- Janssen R, Engel N, Esmail A, et al. Alone but supported: a qualitative study of an HIV self-testing App in an observational cohort study in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(2):467–474. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02516-6

- Anderson C, Breithaupt L, Des Marais A, et al. Acceptability and ease of use of mailed HPV self-collection among infrequently screened women in North Carolina. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94(2):131–137. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2017-053235

- Bertrand JT, Bidashimwa D, Makani PB, et al. An observational study to test the acceptability and feasibility of using medical and nursing students to instruct clients in DMPA-SC self-injection at the community level in Kinshasa. Contraception. 2018;98(5):411–417. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.002

- Cover J, Ba M, Lim J, et al. Evaluating the feasibility and acceptability of self-injection of subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in Senegal: a prospective cohort study. Contraception. 2017;96(3):203–210. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.06.010

- Endler M, Cleeve A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Online access to abortion medications: a review of utilization and clinical outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;63:74–86. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.06.009

- Gizaw M, Teka B, Ruddies F, et al. Uptake of cervical cancer screening in Ethiopia by self-sampling HPV DNA compared to visual inspection with acetic acid: a cluster randomized trial. Cancer Prev Res. 2019;12(9):609–616.

- Murchland AR, Gottschlich A, Bevilacqua K, et al. HPV self-sampling acceptability in rural and indigenous communities in Guatemala: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029158, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-02915

- Polman NJ, de Haan Y, Veldhuijzen NJ, et al. Experience with HPV self-sampling and clinician-based sampling in women attending routine cervical screening in the Netherlands. Prev Med. 2019;125:5–11. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.025.

- Rodrigues LLS, Morgado MG, Sahasrabuddhe VV, et al. Cervico-vaginal self-collection in HIV-infected and uninfected women from Tapajós region, Amazon, Brazil: high acceptability, hrHPV diversity and risk factors. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151(1):102–110. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.08.004.

- Habel MA, Brookmeyer KA, Oliver-Veronesi R, et al. Creating innovative sexually transmitted infection testing options for university students: the impact of an STI self-testing program. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(4):272–277. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000733

- Harichund C, Moshabela M, Kunene P, et al. Acceptability of HIV self-testing among men and women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2019a;31(2):186–192. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1503638

- Ogale Y, Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, et al. Self-collection of samples as an additional approach to deliver testing services for sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4:e001349.