Too often, when it comes to their bodies and health, women live in a culture of silence. In direct and indirect ways, girls and women are taught not to make demands, and learn that sharing their health needs is unlikely to prompt action. In South Asia, as in most of the world, health and development systems reflect and reinforce gender inequalities. Women are under-represented in senior health, government, and development roles, and face high levels of inequity and discrimination.Citation1,Citation2 Research on health priorities, health policies, and the effectiveness of interventions are influenced by historical and current power dynamics, including gender and high/low-income country divides.Citation3 Calls for women's voices to be heard and amplified have increasingly been included in key policy documents including the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals agenda.Citation4 Nevertheless, this “participation” has often been tokenistic, and the power to shape health policies and programmes has largely rested with development and government “experts” rather than with the women and girls they intend to serve.Citation5

Often, development leaders reinforce or fall victim to the paradigms they seek to break down, and use false truisms to brush women's opinions aside. These include: (1) it's too resource intensive and demand approaches at scale don't warrant investment compared to technical solutions, (2) women don't know what they want or need and won't speak openly about “intimate” issues such as sexual or reproductive health, and (3) women's opinions will not be accepted in “patriarchal” societies.Citation6

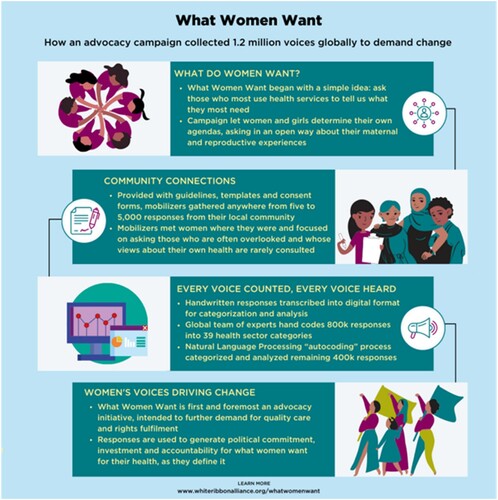

This commentary reflects on the What Women Want: Demands for Quality Healthcare from Women and Girls (WWW) campaign in India and Pakistan, which included views of over half a million women,Footnote† engagement from male and female mobilisers, health providers and decision-makers, and impacted national and district policies, budgets, and communities – in the process dispelling each of these “truisms”. The campaign intended to provide insight into the perspectives and needs of women and girls who use health services. It also served to hold up a mirror to the health and development community about its willingness to understand health demands in a truly women-centred way.

The What Women Want campaign and women-centred development

The origins of the WWW campaign lie with White Ribbon Alliance (WRA) members in India who launched a national campaign called Hamara Swasthya Hamari Awaaz, “Our Health, Our Voice” in 2016 to hear directly from women and girls about their top reproductive and sexual health demands. The aim of the campaign was to elevate women's voices in a way that could lead to constructive dialogue and catalyse effective programme and policy changes. It was designed to focus on women's aspirations concerning the health system – what women want – rather than their critiques.

In 2018, WRA expanded this approach globally, asking women and girls the same question in countries across the globe: “What is your one request for quality reproductive and maternal healthcare services?” This open-ended question let women and girls set the agenda, as opposed to beginning with a premise of what is important or asking them to decide among a set of options. Women were approached by WWW campaign mobilisers through a range of networks and locations, could respond to the question in any language, and could respond on paper, online, or verbally via a facilitator who recorded their response in writing. Women were asked to provide their age and could respond anonymously or voluntarily provide their name and /or photo ().Footnote‡ Importantly, WWW was an advocacy campaign designed to amass a high volume of responses rather than to gather a representative sample.

Process and value of gathering women’s perspectives at scale

Over the course of 14 months, responses were collected from 1.2 million women and girls in 114 countries. The overwhelming majority of responses (98.6%) came from eight countries: India, Pakistan, Kenya, Nigeria, Malawi, Uganda, Tanzania, and Mexico. Participation was highest in India and Pakistan, where responses were collected from approximately 335,000Footnote§ and 245,000 women, respectively. In both countries, the process of capturing women's demands was community-led, hingeing on the efforts of more than 5000 community health volunteers in Pakistan, coordinated by the Rural Support Programmes Network (RSPN), and 114 partner agencies in India.

Each response was digitally recorded by national WWW teams, translated into English, and categorised into relevant thematic categories. About 70% of responses were hand-categorised by trained representatives of the WRA Global Secretariat with quality assurance checks by national staff and campaign mobilisers. The remaining 30% of responses were analysed using natural language processing software and machine learning.

Transcribing and coding 1.2 million responses was a significant undertaking. The initiative was carried out in a reasonable timeframe and with minimal financial resources through the combined efforts of staff at multiple levels of WRA. The sheer number of responses collected from women with differing degrees of literacy in both rural and urban areas dispels the idea that outcomes are not commensurate with the time and effort it takes to meaningfully engage women. The WWW campaign demonstrated that it is not only possible to engage the collective power of thousands of voices in practical dialogue, but also relatively straightforward and cost-effective. It was simply a matter of effective prioritising and partnering.

Women know what they want and will speak up

For many women who shared demands through the WWW campaign, stating a demand was an unfamiliar experience. Smita Bajpai, state coordinator for WRA Rajasthan, India explained, “Their socialization is such that you can share, but you can't demand”. Many coordinators explained that, at first, women were sceptical that their words could lead to improvements in health services or supplies. Women made comments such as, we don't know why you’re asking this, no one cares about our views, people have asked for our opinions before, but nothing has changed, and we are not a priority. However, after learning that their words would become part of a larger campaign, involving women from across the country or globe, women were more eager to share their responses and could easily identify their most salient sexual and reproductive health needs, disproving the common belief that women don't know or won't share.

In India, the top three demands from women were (1) access to maternal health entitlements, (2) improved health services, supplies, and information, including x-rays, drugs, and blood, and (3) respectful and dignified care, including no discrimination or abuse. In Pakistan, top demands included (1) fully functional, closer health facilities, (2) antenatal services and personnel, including ultrasounds and iron supplements, and (3) improving Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH).

Campaign coordinators and community facilitators observed that women often discussed their experiences and demands with one another before deciding on their responses, promoting further engagement in the campaign, and catalysing a larger community conversation. These conversations built solidarity and helped women realise that their collective voice is powerful. As Dr. Smita Bajpai stated, “I think this campaign made women feel valued. Our voice counts. We can make a difference. That was empowering. We have the power, and we can make decisions”. The campaign demonstrated that women and girls are not only willing, but eager to share their sexual and reproductive health needs when they can do so safely and with the assurance that sharing will elicit change.

Listening to women’s demands

Since the campaign findings were published in mid-2019, in the eight countries with the most respondents, more than 30 national and sub-national policy changes have been made, 40,000 health facilities upgraded, 7,000 health workers hired, and nearly US$ 130 million has been mobilised in domestic reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) resources. While there are many factors, local decision-makers have specifically pointed to women's demands as the impetus for these changes, shattering the myth that women's demands won't be accepted or carry weight. In Pakistan, for example, listening to women's demands was crucial to the Provincial Healthcare Commissions deeming RMNCH, family planning, and nutrition services as essential during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province increasing the 2021–2022 family planning budget by 57%. In India, WWW results were shared with key government leaders involved in designing national health policies and programmes, leading to a flurry of research on the needs identified by women and efforts to build the capacity of health professionals in RMNCH.

Across all the campaign countries, policy shifts were accompanied by thousands of facility upgrades, with the largest improvements in WASH. Sujoy Roy, State Coordinator for WRA Bengal, noted that the WWW campaign was powerful because women could see the direct impacts of their participation. He noted,

“99% of the time, what [village women] face is people taking their data then vanishing. This is the first time someone was taking their data then sharing [the results] with them and then changing things. We can tell them, after listening to you, the government has taken these initiatives.”

It was important that campaign approaches moved beyond a tokenistic participatory effort. Therefore, during each stage of the WWW campaign, from asking to action, the process was driven by women who have often been left out of health and development conversations; women were encouraged to share their ongoing experiences and demands, to identify solutions, and to communicate those solutions directly to policymakers. In Pakistan, this occurred, in part, through Listening Sessions, which took place in five districts of Sindh Province and two districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province.Footnote¶ Each session brought together women ranging in age, income, and religion to discuss the most common demands and generate solutions. Women from each session were then selected as representatives to share the results with government officials during follow-up dialogues at the provincial and national levels. While only a small number of Listening Sessions took place, primarily due to the restrictions placed by the government on travel and gatherings because of the ongoing pandemic, they were impactful because participants’ spoken testimonies were backed up by 250,000 transcribed demands from women throughout Pakistan. Similarly, in India, national-level dialogues and public hearings were held to share women's demands with government officials and Chief Medical Officers. Partnerships with media groups created additional platforms to amplify women's words. Importantly, these conversations and displays emphasised solutions rather than solely offering critiques of existing services.

The citizen-led participatory mechanisms utilised by the WWW campaign have begun to be integrated into formal development and government strategies so listening to women will ideally no longer be the purview of a single campaign, but rather business as usual. For instance, Listening Sessions have been added to the Planning Commission PC-1 Form in Sindh Province, Pakistan for the 2021–2025 development budget and policy plan. These strategies have helped governments, health professionals, and civil society organisations understand what is most important to women and girls when it comes to their health and to push for change within countries and communities. In India, a client feedback, community engagement, and grievance redressal mechanism has been included in the SUMAN national operational guideline,Footnote** and WWW has been documented in the World Health Organization/Government of India Compendium of Case Stories from India's Health System, demonstrating the Ministry of Health's commitment to ensuring that women's voices are institutionalised in planning and policy processes.

Expanding the WWW approach

The WWW process demonstrated that it is possible to gather a range of women’s perspectives on a large scale using simple prompts, that women know what they want and will speak up about their health and development demands, and that decision-makers will listen to and respond to women’s demands.

We believe that the key features of this women-centred approach can and should be replicated and institutionalised by governments and development organisations globally. Expanding the types of methodologies used to collect citizen perspectives is critical for complementing national health surveys, which may be missing core elements of women's and girls’ sexual and reproductive health needs.Citation6 By offering an open-ended prompt we were able to amass a more specific and complete picture of how health services can be improved to meet women's needs and create mechanisms for respondents to stay involved in demanding accountability. There is also room for improvement in our approach. As the original goal of the WWW campaign was volume of responses rather than representation, it missed an opportunity to account for how factors like race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and disability influence needs. In future studies and campaigns, ensuring inclusion of vulnerable or excluded women could provide insight into how demands vary across and within populations.

Importantly, many women demanded simple improvements and services, such as improved sanitation and more available medicines. As Smita Bajpai explained, “Despite the MDGs and SDGs, these women are still asking for the basic things”, indicating that we as a health and development community have not adequately prioritised these basic needs. In the process of undertaking this campaign, we found that partner and donor agencies continually expressed resistance to the campaign's approach due to confidence in their own technical expertise, assumptions that they already understand the resonant motivators and barriers to care, and concern that women's answers may lead away from their specific interests. For example, several international donors who focus on RMNCH have expressed frustration that WWW has elevated WASH in healthcare facilities as a maternal health issue, given that many local decision-makers have acted on women's demands and directed funding in this direction at the expense – in the donors’ view – of priority interventions in RMNCH. This resistance reveals how our field is still hesitant to become truly women-centred and to shift the power dynamics of global health such that communities have more self-determination and control of their priorities.Citation7

In 2015, the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition sponsored a panel entitled “Are development agencies failing women?”Citation8 At the heart of the discussion was the argument that aid organisations continue to misunderstand the realities of women's lives because their policies are designed in institutions where women are under-represented, such as governments, banks, and conference rooms, rather than in environments where these women can be heard, such as rural homes or community centres. Even when women's voices are captured, development reports often present a “sanitised” version of women's experiences and demands in order to avoid pushback from government officials, on whom many are reliant for funding and approval.Citation9 The WWW campaign challenged the assumption that this trade-off – diminishing women's voices in favour of continued ability to provide essential sexual and reproductive health services – is necessary. Notably, the WWW methodology did not censor women's words, yet it garnered strong support from government officials and other stakeholders in many countries. This support may be attributed to the volume of responses and framing of demands as aspirational, rather than criticism of existing services. The campaign also highlighted women's multi-dimensional needs, and the problem with having to prioritise when there are many unmet needs.

Even among WWW campaign organisers and in our roles as reproductive health advocates, we underestimated the possibilities and power of asking women what they want. In India, we initially aimed for 50,000 responses and received nearly 350,000. We thought women would want to be anonymous but found that when they believed that their voices would be heard and counted, they wanted to provide their names and follow up. WRA, as a global organisation, was simply a catalyst for existing local partners and communities who took ownership of the campaign and gathered a body of demands more powerful than initially envisioned. If we are to contribute to effectively breaking down the power structures that undermine sexual and reproductive health, we must look at our own principles and practices as international health organisations as much as we look at those of others.

Calls for women's voices to be heard without concerted efforts from international health agencies and governments to follow the demands of those who have been systematically marginalised will not create change. By catalysing important discussions about how we approach health and development and why, and by showing the power of women's collective voices, this methodology created a small crack in the ceiling, which may expand over time. The shifts in power and in women's expectations about being heard produced through this approach should inspire more action from women themselves, as will the results of the actions that we, in the international health and development sphere, take to act on their demands.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people for sharing their experiences and insights of the What Women Want campaign in South Asia to inform this commentary: Smita Bajpai, State Coordinator for White Ribbon Alliance Rajasthan, member of the White Ribbon Alliance India Executive Committee, and Project Director with CHETNA; Sujoy Roy, State Coordinator for White Ribbon Alliance Bengal and Planning Officer for the Child in Need Institute; and Amunullah Khan, Chairman/Director of Forum for Safe Motherhood. We would also like to thank the following members of the WRA Global Secretariat: Diana Copeland, Kristy Kade, Nisha Singh, and Kim Whipkey for their contributions to the manuscript. Finally, we are grateful to each woman and girl who shared her demand for quality maternal and reproductive healthcare.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

† Gender self-identification involves the right of people to identify with the gender of their choice. Regardless of how others view a person, everyone should be free to live and express a gender that feels true to themselves. The WWW campaign included anyone who self-identified as a woman or girl.

‡ Additional details regarding data collection and results from the campaign stratified by age and country are available in the What Women Want Global Results (https://www.whatwomenwant.org/globalfindings), Behind the Demands Reports (https://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Behind-the-Demands_What-Women-Want-Sub-Results-Report.pdf), and Interactive Demands Dashboard (https://whatwomenwant.whiteribbonalliance.org).

§ This number combines the 144,000 responses from the Hamara Swasthya Hamari Awaaz campaign with the 191,000 responses from the expanded WWW campaign.

¶ Additional information on Listening Sessions and WWW campaign outcomes in Pakistan can be found in the following brief: https://fsm.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/LS_Brief.pdf and policy paper: https://fsm.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Policy_Paper.pdf

** The national program, SUMAN, promotes safe pregnancy, childbirth, and immediate postpartum care with respect and dignity by translating the entitlements into service guarantees which are more meaningful to beneficiaries.

References

- Gupta GR, Oomman N, Grown C, et al. Gender equality and gender norms: framing the opportunities for health. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2550–2562.

- Nasrullah M, Bhatti JA. Gender inequalities and poor health outcomes in Pakistan: a need of priority for the national health research agenda. J Coll Phys Surg Pak. 2012;22(5):273–274.

- Topp SM, Schaaf M, Sriram V, et al. Power analysis in health policy and systems research: a guide to research conceptualisation. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(11):e007268.

- UN Women. Women and sustainable development goals; 2016. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2322UN%20Women%20Analysis%20on%20Women%20and%20SDGs.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Delivered by women, led by men: a gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce; 2019. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311322/9789241515467-eng.pdf.

- George AS, LeFevre AE, Schleiff M, et al. Hubris, humility and humanity: expanding evidence approaches for improving and sustaining community health programmes. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(3):e000811.

- Abimbola S, Pai M. Will global health survive its decolonisation? Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1627–1628.

- Moorhead J. Why the development community needs to hear women's voices. The Guardian, 2015 Jul 1. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/jul/01/why-the-development-community-needs-to-hear-womens-voices.

- Storeng KT, Abimbola S, Balabanova D, et al. Action to protect the independence and integrity of global health research; 2019. DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001746