Abstract

This article develops the concept of “menstrual justice”. The legal scholar Margaret E. Johnson has developed an expansive approach to menstrual justice incorporating rights, justice, and a framework for intersectional analysis, with a focus on the US. This framework provides a welcome alternative to the constrictive and medicalised approaches often taken towards menstruation. However, the framework is silent on several issues pertaining to menstruation in Global South contexts. This article therefore develops the concept of menstrual justice in order to extend its relevance beyond the Global North. It presents the findings of mixed-methods research conducted in April 2019 in the mid-western region of Nepal, particularly concerning the practice of chhaupadi, an extreme form of menstrual restriction. We conducted a quantitative survey of 400 adolescent girls and eight focus group discussions, four with adolescent girls and four with adult women. Our findings confirm that dignity in menstruation requires addressing pain management, security issues, and mental health, plus structural issues including economic disadvantage, environmental issues, criminal law, and education.

Résumé

Cet article développe le concept de « justice menstruelle ». La juriste Margaret E. Johnson a mis au point une approche extensive de la justice menstruelle qui inclut les droits, la justice et un cadre pour l’analyse intersectionnelle, l’accent étant mis sur les États-Unis d’Amérique. Ce cadre offre une variante bienvenue aux approches constrictives et médicalisées souvent adoptées face à la menstruation. Néanmoins le cadre est silencieux sur plusieurs questions relatives à la menstruation dans les contextes des pays du Sud. Cet article développe donc le concept de justice menstruelle afin d’élargir sa pertinence au-delà des pays du Nord. Il présente les conclusions d’une recherche à méthodes mixtes menée en avril 2019 dans la région Moyen-Ouest du Népal, en particulier concernant la pratique du chhaupadi, une forme extrême de restriction menstruelle. Nous avons réalisé une enquête quantitative auprès de 400 adolescentes et huit discussions par groupes, quatre avec des adolescentes et quatre avec des femmes adultes. Nos conclusions confirment que la dignité dans la menstruation exige d’aborder la prise en charge de la douleur, les questions de sécurité et la santé mentale, en plus des problèmes structurels, notamment les désavantages économiques, les problèmes environnementaux, le droit pénal et l’éducation.

Resumen

En este artículo se elabora el concepto de ‘justicia menstrual’. La académica jurídica Margaret E. Johnson ha creado un extenso enfoque de justicia menstrual, que incorpora derechos, justicia y el marco de análisis interseccional, centrado en Estados Unidos. Este marco ofrece una alternativa conveniente a los enfoques constrictivos y medicalizados aplicados con frecuencia en relación con la menstruación. Sin embargo, el marco es silencioso en cuanto a varios asuntos relacionados con la menstruación en contextos del Sur Global. Por ello, en este artículo se elabora el concepto de justicia menstrual a fin de extender su pertinencia más allá del Norte Global. Se presentan los hallazgos de una investigación de métodos mixtos realizada en abril de 2019, en la región del medio oeste de Nepal, en particular con relación a la práctica de chhaupadi, una forma extrema de restricción menstrual. Realizamos una encuesta cuantitativa de 400 adolescentes y 8 discusiones en grupos focales, 4 con adolescentes y 4 con mujeres adultas. Nuestros hallazgos confirman que la dignidad en la menstruación requiere abordar el manejo del dolor, asuntos de seguridad y salud mental, así como asuntos estructurales como desventaja económica, cuestiones ambientales, derecho penal y educación.

Introduction

Menstrual activism is “going big”.Citation1 2015 was named the “Year of the Period” by National Public Radio in the United States (US) and recent years have seen widespread media discussion of period poverty, and the so-called tampon tax in the United Kingdom (UK) and US. Scholarship focusing on the Global North has addressed menstruation, focusing on issues such as the tampon tax,Citation2,Citation3 menstrual stigmas,Citation4 and denial of menstrual products to incarcerated women.Citation5–8 There is also a broad range of work occurring in the Global South around menstruation, addressing menstrual health education, access to menstrual products, and broader questions around sanitation and hygiene.Citation9

The legal scholar Margaret E. Johnson has developed an expansive approach to what she terms “menstrual justice” incorporating rights, justice, and a framework for intersectional analysis, with a focus on the US.Citation5,Citation10 This framework provides a welcome alternative to the more constrictive and medicalised approaches often taken towards menstruation.Citation11 However, it is silent on a number of issues pertaining to menstruation in non-US contexts. This article further develops the concept of menstrual justice through an in-depth consideration of our own case study research conducted in Dailekh, a district in Karnali Province in mid-western Nepal. Discussion of this case study highlights a number of issues around menstruation which are under-considered and require a more expansive approach than menstrual hygiene management (MHM) or the more recently defined menstrual health currently allow for.Citation12

This article begins by introducing Johnson’s work on menstrual (in)justice. From here, we discuss the findings of mixed-methods research conducted in the mid-western region of Nepal aimed at understanding women and girls’ experiences of menstruation and menstrual taboos in the region, most notably around the recently criminalised practice of chhaupadi, a severe form of menstrual restriction. Our findings point to ways in which the concept of menstrual injustice might be expanded. To Johnson’s categories of menstrual injustice, we add environmental injustice as well as injustice relating to personal security and further develop the concept of health injustice to include mental health disadvantages. We further draw attention to issues surrounding law, development, and social change, in particular regarding the relative merits of criminal law and school-based education as instruments of social change.

Reproductive justice and menstrual justice

“Menstrual justice”Citation13 is an adaptation of the concept of reproductive justice, pioneered in the 1990s by grassroots organisations advocating for the sexual and reproductive rights of women of colour in the United States. Informed by intersectional research and organising,Citation14 reproductive justice situates reproductive rights within a broader social justice framework. Proponents argue that the mainstream pro-choice movement has focused too narrowly on legal and bureaucratic barriers to abortion access, neglecting the economic and social structures that might inhibit reproductive choice, as well as neglecting areas of sexual and reproductive health and rights that disproportionately affect minority women, such as coerced sterilisation, HIV/AIDS, or fibroids.Citation15–17

Reproductive justice scholarship has not always provided a clear theorisation of menstruation, although much reproductive justice activism in practice has focused on issues such as incarcerated women’s access to menstrual products.Citation18 Echoing Joshi et al,Citation19 Abigail DurkinCitation20 identifies menarche as the point at which those who menstruate first begin to need reproductive justice. Durkin argues that access to adequate menstrual products is vital to women’s substantive equality. Improper use of products – often resulting from poverty or lack of access – is associated with toxic shock syndrome and other health problems, while menstruation itself can be associated with health conditions, such as dysmenorrhoea, requiring regular treatment.

Margaret E. Johnson’s work on menstrual justice develops these insights. Johnson defines menstrual justice in opposition to menstrual injustice: “the oppression of menstruators, women, girls, transgender men and boys, and non-binary persons, simply because they menstruate”. Johnson identifies menstrual injustice as having five categories. The first of these is exclusion and essentialization, in particular the exclusion of transgender men and non-binary people from research and advocacy. The second category is discrimination, harassment and constitutional violations. Johnson cites, for example, cases in which women have been fired from their workplace due to unexpected spotting and staining of furniture.

Johnson’s third category is insults and indignities. These might include the denial of bathroom breaks to menstruating girls, who subsequently are not able to change menstrual products. It could also include the denial of menstrual products to women: in prisons, for example, or in US immigration detention facilities, where girls have been left to bleed through their underwear.Citation21 This category also covers menstrual taboos and stigma. Johnson suggests that more school education on menstruation is required in tandem with the provision of products, observing that lack of education allows menstrual stigma to proliferate, especially among boys. The fourth category, economic disadvantage, affects access to menstrual products as well as potentially to water and sanitation, and is potentially affected by one’s ability to work while menstruating. Finally, health disadvantage is compounded by inadequate medical research on menstruation, lack of effective treatments for conditions such as dysmenorrhoea, and lack of access to hygienic products increasing risk of infection and other health products.

This approach blends an appreciation of the importance of health, hygiene, and access to appropriate products with an awareness that this is not all that there is to menstruation: economic and social structures matter, as do cultural taboos.Citation22 Johnson offers a way forward for assessing menstruation advocacy that, drawing on the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw, employs a “structural intersectionality lens”. This requires recognition that social injustices are rarely “just” about gender, race or any other system of marginalisation and oppression, but rather operate at the intersection of multiple identities. This is true of menstrual injustice; for example, low-income menstruators are disproportionately burdened by measures such as the tampon tax and are also disproportionately people of colour. Approaches which do not recognise the intersectional nature of injustice leave swathes of people without support. Crenshaw herself has famously discussed cases in which Black women who experienced discrimination as Black women were left without legal recourse due to the assumption that discrimination is always unidimensional: either about race or about gender, but never both at once.Citation23 However, our own research in Nepal shows that Johnson’s account misses some significant issues relating to menstruation, in part due to its primary focus on menstrual injustice in the United States. Building from the findings of research conducted in mid-western Nepal, we highlight the ways in which menstrual justice needs to be expanded.

Nepali context

Menstrual restrictions and taboos exist globally, but while taboos may have some general trends, they are also culturally and regionally specific. In Nepal, there are a variety of social practices and restrictions around menstruation. These are mostly related to Hinduism and the particular type of Hinduism practised in Nepal. There is a strong perception that menstruation is related to sin, and menstruating women are considered impure and “untouchable” in most communities. As a result, there are widespread restrictions on women cooking, handling or eating certain food and drink, touching male family members, or sleeping in their usual place.Citation24,Citation25 Menstrual restrictions of some kind impact about 90% of women in the country.Citation26

Chhaupadi represents the extreme end of menstrual restrictions in Nepal (and indeed, the globe). Mainly practised in the mid- and far-west of the country, it involves the above restrictions on movement and interaction, coupled with sleeping in a chhau hut (or sometimes outside), often at some distance from the home.Citation27 Women and girls must stay there during menstruation. Such huts are often open to the elements, have poor ventilation or may be shared with livestock. Chhaupadi was banned by the Nepali Supreme Court in 2005, but no penalties were put in place at the time. Following a series of chhaupadi-related deaths, a new law was passed in August 2017 (and came into effect in August 2018), meaning that enforcement of the practice is now punishable by a fine or imprisonment. Yet only one chhaupadi-related arrest has been made to date, following the death of a young woman named Parwati Budha Rawat, who suffocated inside a chhau hut after lighting a fire to keep warm.Citation28 It is unclear the extent to which people in the mid- and far-west of the country, where chhaupadi is most common, even know about the ban. Furthermore, conversations with Nepali partners during this research suggested that government and police encouragement to destroy chhau huts often has a detrimental effect, such that women and girls may now sleep outside instead with no protection at all.

Methods

Our study was conducted in Dailekh district (Karnali Province, mid-western Nepal), as it is believed that the practice of chhaupadi is very common in this district.Citation29 We selected one rural municipality (Bhairabi) and one urban municipality (Dullu). Dailekh is a hilly district with poor access to water sanitation and hygiene infrastructure (51% of households do not have a toilet), low age at first marriage (82% married before the legal age of 20), and an average population density of around 174 people per square kilometre. As of 2013, the majority of the population depends on agriculture.Citation30

The study adopted a mixed-methods approach consisting of a quantitative survey and a qualitative study. We collected quantitative data from 400 adolescent girls aged 14–19 using two-staged cluster random sampling. Our approach meant it was only possible to gather data on cisgender women and girls; transgender or anya (third gender) individuals are not included in this study. One previous study in Nepal found that 44% of girls in the far- and mid-western regions reported that they were asked to observe chhaupadi.Citation31 Assuming similar levels of prevalence for menstruation-related outcomes, we would require about 386 in our sample with power = 0.80 and alpha = 0.05. Therefore, a total of 400 respondents were surveyed to account for any non-response (though this turned out to not be an issue). Our study was conducted in one rural municipality (Bhairabi) and one urban municipality (Dullu) of Dailekh district, Karnali Province in Nepal in April 2019. The survey was conducted in person by Nepali interviewers using the kobo tool. The field team approached the household head of selected households initially to screen for eligible adolescent girls; if adolescent girls were present then the field team took written, informed consent from the household head and conducted a short interview about the household. Written, informed consent was then taken from adolescents prior to conducting the survey with them. Where adolescents were aged less than 18 years, consent was obtained from the girl’s guardian before obtaining her assent. Data were anonymised at the point of collection.

The survey included seven sections; these were (1) socioeconomic and demographic information, (2) knowledge and perception regarding menstruation, (3) practice regarding menstruation, (4) beliefs and attitudes regarding menstruation, (5) psychosocial scales, (6) mental health, and (7) suggestions for change. Aside from knowledge, attitudes and practice, adolescent girls were also asked about the effects that menstruation and menstrual taboos have on them in terms of mental health and psycho-social impacts. Depression was measured using the Nepali Depression Self-Rating Scale described by Kohrt et al.,Citation32 which measures depressive symptoms on a scale of 0–32, with scores of 12 and above indicating likely clinical depression. Our final sample consisted of 365 girls who had experienced menarche and 35 who had not.

Statistical analyses of data in this paper are mainly descriptive; they provide a summary of how the experiences of the girls in our survey relate to the categories of menstrual justice. The exception to this is depression, which was analysed using logistic regression where the independent variable was whether the girl was currently experiencing depression or not and the dependent variable was practising chhaupadi. An unadjusted model was produced as well as an adjusted model (including age, caste/ethnicity, marriage, pain, education, socioeconomic status, and municipality), which was produced to determine if any relationship between chhaupadi and depression could be explained through these other variables. None of the variables included in this paper had any missingness thanks to the in-person data collection and use of experienced enumerators. All analyses were conducted using Stata MP 15.

To obtain a more nuanced understanding of the issues surrounding menstruation in the area we also conducted eight focus group discussions (FGDs), four with adolescents aged 18–19 (none of whom participated in the quantitative study) and four with women aged 25–45 years old. Participants were identified through liaison with local stakeholders at the community level. 35 adolescents and 36 women aged 25–45 participated in the FGDs, which were conducted in Nepali and facilitated by Nepali researchers from the Centre for Research on Environment, Health and Population Activities (CREHPA). The informed consent process was explained and participants were asked to sign the consent form before starting the discussion.

FGD participants were read a story about a hypothetical girl named Sita who lived in Dailekh and was experiencing menstruation for the first time. The discussion that followed was based upon a series of open-ended questions relating to Sita and the participants’ own experiences of menstruation. These discussions were audio recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. The transcripts were analysed thematically allowing the data to be coded into multiple categories simultaneously. Open coding was employed using the software QSR NVivo v.11 to avoid excluding unexpected data, and illustrative quotations have been selected below in order to demonstrate the key themes arising from these discussions. We analysed the quantitative and qualitative data in a combined way and the qualitative data were mainly used to complement and supplement the quantitative data.

Findings and discussion

The socio-demographic characteristics of participants in the focus group discussions and quantitative survey are presented in . The characteristics of the qualitative and quantitative participants differ, largely due to the wider age range in the FGDs. In the qualitative sample (n = 71), 34% of participants had primary education or below, while in the quantitative survey (n = 400) that decreased to 29% of girls, reflecting the increase in levels of education in recent years. The majority of respondents were Brahmin or Chhetri, and Dalits were well-represented in both the qualitative and quantitative samples. However, the quantitative sample includes several castes/ethnicities that were not included within the qualitative, such as Thakuri, Sanysi, and Dasnami. Agriculture (including livestock and horticulture) was the main source of income for 70% of households in the quantitative survey. We asked about the occupation of the FGD participants rather than about household income; the largest category (34%) was student/unemployed while 27% reported agriculture. 62% of FGD participants were married compared to 23% of quantitative respondents, which is again due to the difference in age composition.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

The overall objective of the study was to understand the barriers to good menstrual hygiene and examine socio-psychological and health consequences among adolescent girls. The project was conceived as a scoping study and thus the questions asked in the focus group discussions were open and the quantitative survey covered a very wide range of topics relating to menstruation beyond hygiene. While the study had not originally been conceived as being about menstrual justice, the results indicated that menstrual hygiene was not an adequate conceptualisation of what we were trying to study, and required the development of a more appropriate framework.

Developing the menstrual justice framework

Our findings highlight how the concept of menstrual justice might be expanded to more fully encapsulate the experience of menstruation. They lend support to Johnson’s framework, showing how both economic disadvantage and health disadvantage (in this case, pain and lack of access to effective pain management) may have a detrimental impact on the dignity and wellbeing of those who menstruate. However, the findings also suggest areas in which the concept of menstrual injustice might be developed. They suggest, first of all, that the category of health disadvantage can be expanded to include mental health disadvantage. Further, our findings demonstrate the need to add further categories of menstrual injustice relating to security, environmental injustice, and state power and the law.

Economic disadvantage

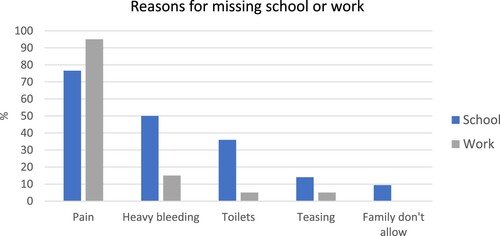

The focus group findings reaffirm the argument of Johnson and others that economic disadvantage substantially inflects the experience of menstruation. In addition to the prohibitive cost of pain medication, the focus group discussions repeatedly pointed to the cost of menstrual materials as a problem, with 51% of the 142 girls who reported wanting to switch to pads saying they did not use their preferred method due to cost (see ). Women and adolescent girls instead used old clothes and rags to catch menstrual blood:

“In villages, most of the people have a joint family. Let’s say that there are about 8 girls in the house who menstruate – 5 sisters, 2 sisters-in-law, and a mother. It is not possible for the family to buy pads every month for 8 people. Hence, they switch to a more economical way and use cloths. Some even face problems with using cloths.” (19-year-old, Dullu)

Figure 1. The distribution of reasons given for not using a sanitary pad when this is the preferred option (n = 142, multiple responses possible)

“Pads aren’t available here and just wanting it won’t do. It should be available so that women can use it. Since it is not available, women use cloths.” (26-year-old)

“It is expensive as well. The marketplace is also far.” (43-year-old)

“It is because we don’t have money. If we have money, distance doesn’t become a problem.” (35-year-old)

Health disadvantage

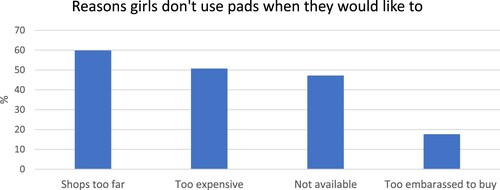

The findings also support this element of Johnson’s framework, showing that period pain has a substantially disruptive effect on girls’ lives. Of course, pain may have a negative impact on wellbeing beyond the disruption to work and school. The survey data shows that while 60% (n = 219) of menstruating girls experienced period pain, only 16% of those girls took painkillers. Of those who did take painkillers (n = 58), 83% found them to be effective. Due to lack of access to painkillers, girls might instead use other methods such as drinking hot water and tying cloth around the waist, but only a third found these to be effective. 40% of the 219 girls who reported pain used no pain management method at all. The survey found an impact here on work and school, with 32% (20) of the 63 girls who worked having missed work in the last 12 months due to their period, and 27% (64) of the 234 girls currently in school having missed school in the last 12 months due to their period (see ). The overwhelming majority of those who had missed work or school reported that this was due to period pain, with 95% of those who missed work and 77% of those who had missed school reporting period pain as one of the causes. This was reinforced in the focus group discussions. As a 19-year-old student in Dullu put it, “Schools are far from home and we have stomach pain during menstruation. Therefore, many girls don’t go to school. They stay at home when they have such problems”. This was compounded by the lack of availability of pain medication. Young women repeatedly stated that they would like to see medication offered in schools. Lack of access to pain medication was a key issue for older women too; several stated that they did not have enough money to buy medicine.

Moving beyond Johnson’s framework

Crucially, the social stigma of menstruation, coupled with the absence of safety and security discussed below, has a clear impact on mental health. Practising chhaupadi is correlated with a higher likelihood of depression. In fact, adolescents who practised chhaupadi (281 of 365 who had started menstruating) were around 80% more likely to be experiencing depression. The depression self-rating scale measures depressive symptoms on a scale of 0–32, with scores of 12 and above indicating likely clinical depression. The mean score was 11, with 43% scoring 12 or above (indicating suspected clinical depression). For those who practised chhaupadi, the mean score was 12 compared to 9 for those who did not. This association was statistically significant (p-value = 0.009) and remained robust when controlling for a variety of socioeconomic factors (education, socioeconomic status, marriage, pain, caste/ethnicity, and municipality), though further research is needed to determine whether this is a causal effect.

Issues with mental health and wellbeing associated with chhaupadi were also repeatedly stressed in the focus group discussions, among the younger and older groups of women alike. The younger women stated that “girls feel heart-broken when they are asked to follow these practices” (19-year-old, Dullu) and that “They feel disgusted. They think that it would have been a lot easier if they were born a boy” (18-year-old, Dullu). “Practising the chhaupadi tradition decreases the self-esteem of girls and makes them feel violated” (19-year-old, Dullu). Some women in the older groups worried that if something bad happened, such as livestock becoming ill, they might have caused it by breaking menstrual taboos – particularly if blamed for this by older relatives. “We ourselves feel scared. We feel that maybe we did something wrong that resulted in all this” (26-year-old, Dullu). Clearly, mental health must be a concern beyond the immediate context of chhaupadi; menstrual stigmas in general exacerbate mental health disadvantage even when they do not require extreme restrictions.Citation4 The category of health disadvantage must explicitly include mental health.

Security and personal safety

This is the first of our additions to Johnson’s framework. In the context of chhaupadi, menstrual stigmas do not only operate as “insults and indignities” resulting in shame and humiliation, but also operate as a detriment to the safety of women and girls. Our findings show that menstrual taboos in Dailekh put women and girls in dangerous situations. The focus group discussions repeatedly saw participants raise concerns about their physical safety during the practice of chhaupadi. Many of these fears were related to the threats posed by wild animals whilst sleeping in chhau huts or outdoors, especially snakes: “sometimes, women have to stay under the fear of snakebite while staying in the chhau shed. They also fear wild animals while staying near the jungle” (43-year-old, Dullu). For some participants, this was not simply a fear; they had heard of real instances of women being bitten by snakes: “It happened 3–4 months ago. A woman was bitten by a snake while she was sleeping inside a chhau shed. Unfortunately, she died” (19-year-old, Dullu).

Participants also raised the possibility of being attacked by men whilst alone in chhau huts at night, with some claiming there had been instances where women staying alone were raped. This was clearly a significant fear for many participants: “Women fear whenever they hear of incidents of rape in the shed. Women sleep the entire night but they sleep in fear” (19-year-old, Dullu). While our data do not include concrete evidence of attacks by animals or humans on participants in this study (although evidence of this is present in other studiesCitation25), this was, nonetheless, clearly a real fear for women and girls that, as discussed below, had a significant impact on their mental health. The fear of potential attack had a detrimental effect on participants’ sense of personal security and safety during menstruation.

The security risks faced by those who practise chhaupadi have been well documented by the international media, which has arguably been the impetus for domestic legal change. The reproductive rights literature is increasingly interested in the links that reproductive rights have to security.Citation33 As detailed above, the practice of chhaupadi moves beyond invisible social stigma to present material security concerns. Of all of our proposed categories, this may seem the most specific to the Nepali context; as we have noted, chhaupadi is at the extreme end of menstrual restrictions globally, and the majority of people who menstruate will not experience security risks of this type. However, Nepal is not the only place where those who menstruate face restrictions or even isolation during menstruation.Citation34,Citation35 We therefore need to pay attention to the impact that menstrual taboos, stigma and restrictions can have on the livelihood and (sense of) safety and security of those who menstruate.Citation36

Environmental injustice

Johnson’s framework does consider environmental issues to an extent, such as the potential health impacts of pollutants found in some menstrual products and the difficulty of finding environmentally-safe products for menstruators living in poverty.Citation5 However, our study indicates that environmental injustice, especially relating to the disposal of menstrual products, should be added as its own category of menstrual injustice. The survey showed that disposal of pads was problematic due to lack of local waste disposal services, with 35% of the 88 adolescents who used them disposing of them outside in the field, river or jungle where due to their plastic content they will not degrade for thousands of years. A further 35% buried them, which is still problematic environmentally, while 17% burned them (creating potentially toxic fumes), and the remainder put them down the toilet or in the bin. In the focus group discussions, participants were aware of the immediate environmental problems that outside disposal might cause:

“Some throw the used pad in the forest or rivers which pollutes the environment.” (18-year-old, Bhairabi)

“There are many germs in these clothes. When they are deposited in riverbanks, flies sit on them and the same flies might sit on our food. Hence, the food gets contaminated and we suffer from diseases.” (18-year-old, Dullu)

Nepal is not alone in this problem: insufficient infrastructure for the waste management of disposable sanitary pads and tampons in many parts of the Global South has resulted in sewer line blockages, pollution of local water courses as well as air pollution and health risks in the immediate environs when menstrual products are burned.Citation37,Citation38 As A. E. Kings has argued, the causes and consequences of this pollution are inflected by religion, caste, and class as well as gender, so need to be analysed intersectionally.Citation39 If more people who menstruate start using disposable pads, the method of disposal needs serious consideration in order to avoid substantial plastic pollution in areas such as the one in which our study took place, where there is no organised waste disposal system. More sustainable options include menstrual cups and period pants, both of which can be used for many years and offer more protection against leaks and discomfort as compared to cloth, yet participants were generally not aware of methods other than the ones they were using. While we do not have data on this, it is unlikely that participants would have been aware of sustainable options or have the ability to access them.

As global awareness of menstrual issues has been growing, so too has understanding of environmental issues. Much of this discourse has focused on plastic pollution, and there has been a broad movement against single-use products. Interventions relating to menstruation often focus on the provision of single-use products. Yet the plastic in single-use menstrual materials breaks down slowly and can have a hugely negative long-term environmental impact. Equally, as stressed in the focus group data above, there are more immediate environmental impacts in communities and countries which lack centralised waste disposal programmes. The environmental impact of sanitary produce is increasingly gaining attentionCitation38 but is not addressed in the current definition of MHM.

State power and the law

Finally, we add state power and the law as a dimension of menstrual (in)justice. The findings from Nepal indicate the need for attention to a swathe of issues surrounding the use of state power as a means of bringing about social change. In the Global North, much has been written about taxes on menstrual products – the “tampon tax” – and the various efforts to litigate and legislate against these.Citation5,Citation20,Citation40 There has been equal discussion of attempts to legislate access to free menstrual products in various countries.Citation41 In many countries, menstrual leave policies have been enacted, including Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Zambia (although there are issues around efficacy and uptake).Citation42 In Nepal, however, efforts to combat menstrual taboos have harnessed the criminal law: a statute criminalising the practice of chhaupadi, a form of menstrual taboo imposing isolation during menstruation, came into effect in August 2018. The new law was welcomed at the time by many NGOs and campaigners. Yet our research raises questions about the appropriateness and effectiveness of criminal law as a means of enacting social change.

The survey and focus group discussions demonstrate the failure of criminalisation as an approach to ending menstrual stigma. 60% (239) of our survey respondents knew that chhaupadi was illegal, yet adolescents who knew about the law were just as likely to practise chhaupadi as those who did not know it was illegal. Overall 45% (181) of respondents thought that the law would stop people practising chhaupadi; however, those who knew chhaupadi was illegal were significantly less likely to think that this would change the practice. Of the 281 girls who practised chhaupadi, only 50 (18%) thought that women and girls should do so. Interestingly, 7% of the 84 girls who did not practise it thought that they should.

The focus group discussions similarly demonstrated mixed awareness as to the legal status of chhaupadi. Some participants were not aware that the practice is illegal. Most were aware, having learned from sources such as the radio or from visitors to their village. Those who were unaware of the law sometimes expressed the hope that if chhaupadi were made illegal, the practice would end: “If they know it is illegal, they would stop practising it due to fear” (18-year-old, Bhairabi). Others disagreed: “Even if people knew that chhaupadi is illegal, many won’t accept and follow the law. They are not scared as they think that no one will be knocking every door to check” (31-year-old, Bhairabi). Meanwhile, those who were aware of the law stated that it had not changed the situation in practice, in most cases due to elders reinforcing the practice.

“In our ward there has been a rule of not keeping the daughters in chhaupadi shed and if someone is found doing such, they have to pay Rs. 2,500 as fine as per the law. But this rule hasn’t been implemented. The one who started the rule himself practises chhaupadi.” (19-year-old, Dullu)

What can be done?

The failure of criminalisation raises questions about what else might be done to combat chhaupadi. Here, the temptation is to turn to school-based education on menstruation. Development interventions have typically focused on schooling and education, using schools to distribute menstrual products and to educate girls about menstruation and its management. In the focus group discussions, education was consistently identified as the primary reason for changes to menstrual practices. Adolescents were, on the whole, well informed about menstrual hygiene and many (although not all) expressed scepticism towards traditional beliefs about the uncleanliness of menstruation. Some participants laughed when discussing elders’ beliefs or pointed out that “if no one knows that we are menstruating, nothing will happen even when we touch people” (19-year-old, Dullu).

Such initiatives resemble Johnson’sCitation5 suggestion that schools might play a role in tackling menstrual stigma (although, crucially, Johnson emphasises the need to educate boys about menstruation). Yet as Chris Bobel has argued,Citation1 these development interventions have in practice placed too great a burden on girls as agents of change and are limited in their ability to challenge broader power structures. Our findings indicate a clear gap between what girls and young women learn about menstruation at school and what they are able to put into practice at home. As a 19-year-old student in Dullu stated:

“We have to agree to what our elders have said. Even if we know that menstruation is a normal event, we have to stay quiet and pretend as if we don’t know about it. […] I think one of the biggest drawbacks is that even the educated people are not able to convince the older generation.”

Our research demonstrates that education has an important role to play, but this role is limited. There are clear ramifications of this for development initiatives. Development work tends to focus on education and to see schools as a viable site for interventions, but our findings suggest that such interventions alone cannot prevent or change chhaupadi. Moreover, the most disadvantaged young people do not attend school, so will be further marginalised by school-centred approaches. Education-based policies need to place greater emphasis on community-based education outside of school settings and bring community leaders and families, including men and boys, into the conversation around menstruation as well.

Study limitations and future research

Our research lends support to Johnson’s menstrual justice framework, demonstrating the impact of economic and health injustice on those who menstruate. However, it also suggests ways in which the framework can be extended: by incorporating mental health into health disadvantage, and adding categories addressing safety and security, environmental injustice, and state power and the law. This article intends to continue a conversation, rather than present the definitive account of menstrual justice. Our own research contains silences; nonetheless, the data suggest some potentially fruitful avenues for further research in this area. The first of these concerns geography. Dailekh district has poor infrastructure and access to roads and markets is limited; participants in our study complained of their inability to access a marketplace where they could buy menstrual products and the long distances and travel times required (see ). Inquiry into geographies of menstruation might be productive for those researching issues of menstrual justice.

Research on menstrual justice might also seek to develop a more holistic understanding of education, extending beyond the classroom setting. Our own research suggests that the biggest impediments to change were not girls and young women themselves, who were well informed about menstruation and its management but came up against older relatives and the strictures imposed by traditional healers. However, our research design meant that we only reached women aged 45 and under, not entire communities. Researchers might then inquire into community dynamics – encompassing the older generation, and religious leaders and healers – and ask how educational initiatives might target the entire community, including bringing those who are most resistant to change around chhaupadi into the conversation.

Finally, our study only addresses the experiences of cisgender women and girls and not those of others who menstruate. Nepal has officially recognised a third gender category (anya or “other”) since 2007.Citation44,Citation45 International research and media coverage on third-gender individuals in Nepal has tended to focus on metis (male-assigned people with a female gender identity and/or feminine gender presentation). Yet anya is a much broader category than this (and often contested).Citation46 The first two Nepali citizens to receive legal recognition as anya were assigned female at birth. Despite their clear presence in Nepal, researchers know little about this group, let alone about their experiences of menstruation. Research in US contexts has demonstrated that transgender men and boys face particular challenges relating to menstruation.Citation47–49

As Swatija Manorama and Radhika Desai observe while reflecting on how Indian health policies address menstruation, menstrual justice “can serve as the basis for compelling the state to dismantle edifices built on the designation of menstruating … women’s bodies as ‘impure’”.Citation22 Our research accentuates the need for holistic understanding of women and girls’ lives and social circumstances. An expanded understanding of menstrual justice, which includes attentiveness to the personal and systemic issues highlighted above, goes some way to doing this.

Ethics

Ethical clearance for this research was obtained from the Nepal Health Research Council (Ref 36/2019, approved on 13 February 2019) and the Social Science Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bath (reference no. S19-001, approved on 28 March 2019). This work was supported by the GCRF 18/19 (project title “Menstrual Taboos and Menstrual Hygiene Policy in Nepal: A Multi-Method Scoping Study to Understand the Barriers to Good Menstrual Hygiene for Adolescent Girls”).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bobel C. The managed body: developing girls and menstrual health in the global south. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2019; p.5.

- Cotropia CA, Rozema K. Who benefits from repealing tampon taxes? Empirical evidence from New Jersey. J Empir Leg Stud. 2018;15(3):620–647.

- Ooi J. Bleeding women dry: Tampon taxes and menstrual inequity. Northwest Univ Law Rev. 2018;113(1):109–153.

- Johnston-Robledo I, Chrisler JC. The menstrual mark: menstruation as social stigma. Sex Roles. 2013;68:9–18.

- Johnson ME. Menstrual justice. UC Davis Law Review. 2019;53(1):45–47.

- Goldblatt B, Steele L. Bloody unfair: inequality related to menstruation – considering the role of discrimination law. Sydney Law Rev. 2019;41(3):315–320.

- Bozelko C. Opinion: prisons that withhold menstrual pads humiliate women and violate basic rights. In: C Bobel, editor. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020. p. 49–52.

- Roberts T. Bleeding in jail: objectification, self-objectification, and menstrual injustice. In: C Bobel, editor. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020. p. 53–68.

- Lahiri-Dutt K. Medicalising menstruation: a feminist critique of the political economy of menstrual hygiene management in South Asia. Gend Place Cult. 2015;22(8):1158–1176.

- Crays A. Menstrual equity and justice in the United States. Sexual, Gend Polic. 2020;3/2:134–147.

- Thomson J, Amery F, Channon M, et al. What’s missing in MHM? Moving beyond hygiene in menstrual hygiene management. Sex Reprod Health Matter. 2019;27(1):12–15.

- Hennegan J, Winkler IT, Bobel C, et al. Menstrual health: a definition for policy, practice, and research. Sex Reprod Health Matter. 2021;29(1):31–38.

- Kissling EA. Capitalizing on the curse: The business of menstruation. Boulder: Rienner; 2006.

- Ross LJ. Reproductive justice as intersectional feminist activism. Souls: A Crit J Black Polit, Cult Soc. 2017;19(3):286–314.

- Gerber Fried M. Transforming the reproductive rights movement: the post-Webster agenda. In: M Gerber Fried, editor. From abortion to reproductive freedom: transforming a movement. Boston, MA: South End Press; 1990. p. 1–14.

- Luna Z. From rights to justice: women of color changing the face of US reproductive rights organising. Soc Without Bord. 2009;4(3):343–365.

- Ross LJ, Solinger R. Reproductive justice: an introduction. Oakland (CA): University of California Press; 2017.

- Haven K. “Why I’m fighting for menstrual equity in prison,” ACLU News & Commentary (November 8, 2019). Available from: https://www.aclu.org/news/prisoners-rights/why-im-fighting-for-menstrual-equity-in-prison.

- Joshi D, Brut G, González-Botero D. Menstrual hygiene management: education and empowerment for girls? Waterlines. 2015;34(1):51–67.

- Durkin A. Profitable menstruation: how the cost of feminine hygiene products is a battle against reproductive justice. Georgetown J. Gen Law. 2017;18(1):131–172.

- Buncombe A. Trump Administration leaves menstruating migrant girls “bleeding through” underwear at detention centres, lawsuit claims. The Independent. 30 August, 2019. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/trump-immigration-migrant-children-border-lawsuit-period-tampon-latest-a9081341.html

- Manorama S, Desai R, Menstrual justice: a missing element in India’s health policies. In: C Bobel, editor. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020. pp. 511–527.

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;141:139–167.

- Crawford M, Menger LM, Kaufman MR. “This is a natural process”: managing menstrual stigma in Nepal. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(4):426–439.

- Amatya P, Ghimire S, Callahan KE, et al. Practice and lived experience of menstrual exiles (chhaupadi) among adolescent girls in far-western Nepal. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208260.

- Kadariya S, Aro AR. Chhaupadi practice in Nepal – analysis of ethical aspects. Medicoleg Bioeth. 2015;5:53–58.

- Ranabhat C, Kim C, Choi EH, et al. Chhaupadi culture and reproductive health of women in Nepal. Asia Pac J Public Healt. 2015;27(7):785–795.

- Singh P. “Banished from home, Accham woman dies in menstrual hut,” The Himalayan Times (2 December, 2019). Available from: https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/banished-from-home-achham-woman-dies-in-menstrual-hut/.

- Paudel R. Situational analysis on menstrual practice in Dailekh (Radha Paudel Foundation, 2017). Available from: http://www.radhapaudelfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Dailekh-Mesntrual-Assessment_-Final-report-June-2017.pdf.

- UNFCO. District Profile: Dailekh (RCHC Office, Nepal, 2013) p. 7. Available from: https://un.info.np/Net/NeoDocs/View/4201.

- Amin S, Bajracharya A, Chau M, et al. “UNICEF Adolescent Development and Participation (ADAP) Baseline Study: Final report” (New York: Population Council, 2014) p 42. Available from: https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2014PGY_NepalADAP-Baseline.pdf.

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Tol WA, et al. Validation of cross-cultural child mental health and psychosocial research instruments: adapting the depression self-rating scale and child PTSD symptom scale in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:127.

- Davies SE, Harman S. Securing reproductive health: a matter of international peace and security. Int Stud Q. 2020;62(2):277–284.

- Sarah SJ, Ryley H. It’s a girl thing: menstruation, school attendance, spatial mobility and wider gender inequalities in Kenya. Geoforum. 2014;56:137–147.

- Joshy N, Prakash K, Ramdey K. Social taboos and menstrual practices in the Pindar Valley. Indian J Gend Stud. 2019;26(1&2 ):79–95.

- Hennegan J, Shannon AK, Rubli J, et al. Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(5):e1002803.

- Elledge MF, Muralidharan A, Parker A, et al. Menstrual hygiene management and waste disposal in low and middle income countries: a review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2562.

- van Eijk AM, Sivakami M, Thakkar MB, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;2(6/3):e010290.

- Kings AE. Intersectionality and the changing face of ecofeminism. Ethic Environ. 2017;22(1):63–87.

- Crawford BJ, Spivack C. Tampon taxes, discrimination, and human rights. Wis L Rev. 2017;3:491–454.

- Cousins S. Rethinking period poverty. The Lancet (British Edition). 2020;395(10227 ):857–858.

- Barnack-Tavlaris JL, Hansen K, Levitt RB, et al. Taking leave to bleed: perceptions and attitudes toward menstrual leave policy,. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(12):1355–1373.

- Singh P. “Locals tear down Chhaupadi huts amid wide concern over deaths in sheds.” The Himalayan Times (17 January, 2019). Available from: https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/locals-tear-down-chhaupadi-huts-amid-wide-concern-over-deaths-in-sheds/.

- Bochenek M, Knight K. Establishing a third gender category in Nepal: process and prognosis. Emory Int Law Rev. 2012;26:11–41.

- Boyce P, Coyle D. Development, discourse and law: transgender and same-sex sexualities in Nepal (IDS sexuality. Poverty and Law Evidence Report. 2013;13.

- Knight K, Flores AR, Nezhad SJ. Surveying Nepal’s third gender: development, implementation, and analysis. Transgen Stud Quart. 2015;2(1):101–122.

- Chrisler JC, Gorman JA, Manion J, et al. Queer periods: attitudes toward and experiences with menstruation in the masculine of centre and transgender community. Cult Healt Sexual. 2016;18(11):1238–1250.

- Frank SE. Queering menstruation: trans and non-binary identity and body politics. Sociol Inq. 2020;90(2):371–404.

- Lane B, Perez-Brumer A, Parker R, et al. Improving menstrual equity in the USA: perspectives from trans and non-binary people assigned female at birth and health care providers. Cult Healt Sexual. 2022;24(1):1408–1422.