Abstract

As an interface between health and education, comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) offers a potent tool among other interventions to accelerate healthy transition of adolescents into adulthood. With increasing interest in in-school CSE provision/delivery, young people in out-of-school contexts may be left behind. This study forms part of implementation research to understand if the activities used to train and support the facilitators are feasible, appropriate, acceptable, and effective in enabling them to engage a defined group of young people, deliver CSE to them in the out-of-school context, and assist them in obtaining relevant services. This paper presents findings of mapping of out-of-school CSE interventions in Ghana, ongoing or completed between 2015 and 2020, and then discusses a needs assessment of two purposively selected groups of vulnerable out-of-school youth: young people living with HIV and AIDS (YPLHIV) and those living in detention (YPiD). We conducted 10 interviews with YPLHIV and three focus group discussions with YPiD in November 2020. Qualitative data were analysed thematically using both deductive and inductive approaches. The mapping yielded 29 interventions (18/62% were ongoing) focused extensively on the delivery of CSE-related knowledge and information; none were aimed at building facilitators’ capacity and most targeted the northern regions. Among YPLHIV, living positively after diagnosis, disclosure skills and use of HIV/AIDS health services were critical. YpID sought clarification on personal hygiene, consent in sexual relationships, medium/channel to deliver CSE, and issues around same-sex sexual intercourse. Both groups sought skills in dealing with stigmatisation and discrimination. Implications of the findings for our own and other interventions are highlighted.

Résumé

En tant qu’interface entre la santé et l’éducation, l’éducation complète à la sexualité (ECS) constitue un outil puissant parmi d’autres interventions pour accélérer la transition de l’adolescence à l’âge adulte en bonne santé. Compte tenu de l’intérêt croissant pour l’ECS dispensée en milieu scolaire, les jeunes dans des contextes déscolarisés risquent d’être laissés de côté. Cette étude fait partie d’une recherche en matière de mise en œuvre destinée à comprendre si les activités utilisées pour former et soutenir les facilitateurs sont faisables, adaptées, acceptables et efficaces pour leur permettre d’associer un groupe défini de jeunes, de leur dispenser une ECS dans le contexte non scolaire et de les aider à obtenir des services pertinents. L’article présente les conclusions de l’inventaire d’interventions extrascolaires d’ECS au Ghana, en cours ou achevées entre 2015 et 2020, puis examine une évaluation des besoins de deux groupes sélectionnés à dessein de jeunes vulnérables déscolarisés: des jeunes vivant avec le VIH et le sida ou vivant en détention. En novembre 2020, nous avons mené dix entretiens avec des jeunes vivant avec le VIH et le sida et trois discussions de groupe avec des jeunes vivant en détention. Des données qualitatives ont été analysées de manière thématique en utilisant des méthodes à la fois déductives et inductives. L’inventaire a trouvé 29 interventions (18/62% en cours) largement concentrées sur la prestation de connaissances et d’informations relatives à l’ECS; aucune ne visait à renforcer les capacités des facilitateurs et la plupart ciblaient les régions septentrionales du pays. Pour les jeunes vivant avec le VIH et le sida, il était essentiel de vivre positivement après le diagnostic, de posséder les compétences en matière de révélation et de pouvoir utiliser les services de santé prenant en charge le VIH/sida. Les jeunes vivant en détention souhaitaient des précisions sur l’hygiène personnelle, le consentement dans les relations sexuelles, le moyen/la voie pour dispenser l’ECS et les questions autour de rapports sexuels entre personnes du même sexe. Les deux groupes recherchaient des compétences leur permettant de faire face à la stigmatisation et la discrimination. Les conséquences des conclusions pour notre propre intervention et d’autres activités sont mises en avant.

Resumen

Como interfaz entre salud y educación, la educación integral en sexualidad (EIS) constituye una herramienta potente entre otras intervenciones para acelerar la sana transición de la adolescencia a la adultez. Debido al creciente interés en la provisión/entrega de EIS en las escuelas, las personas jóvenes que se encuentran fuera de la escuela podrían quedarse abandonadas. Este estudio forma parte de la investigación operativa para entender si las actividades utilizadas para capacitar y apoyar a facilitadores son factibles, adecuadas, aceptables y eficaces para permitirles atraer a un grupo definido de jóvenes, enseñarles EIS en contextos fuera de la escuela y ayudarles a obtener servicios pertinentes. Este artículo presenta los hallazgos de mapear intervenciones de EIS fuera de la escuela, en curso o concluidas entre los años 2015 y 2020 en Ghana, y analiza una evaluación de necesidades de dos grupos de jóvenes fuera de la escuela seleccionados intencionalmente: jóvenes que viven con VIH y SIDA (JVVIH) y jóvenes que viven en detención (JeD). En noviembre de 2020, realizamos 10 entrevistas con JVVIH y tres discusiones en grupos focales con JeD. Analizamos los datos cualitativos temáticamente utilizando enfoques deductivos e inductivos. El mapeo produjo 29 intervenciones (18/62% en curso) enfocadas extensamente en la provisión de información y conocimientos relacionados con EIS; ninguna estaba destinada a desarrollar la capacidad de los facilitadores; la mayoría estaba dirigida a regiones septentrionales. Para JVVIH, era fundamental vivir positivamente después del diagnóstico, poseer habilidades de divulgación y usar los servicios de VIH/SIDA. JeD buscaban aclaración sobre higiene personal, consentimiento en relaciones sexuales, medios/vías para impartir EIS y asuntos relacionados con el coito sexual entre personas del mismo sexo. Ambos grupos buscaban habilidades para superar la estigmatización y discriminación. Se destacan las implicaciones de los hallazgos para nuestra intervención y otras intervenciones.

Introduction

Access to timely, appropriate, and comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information and education by young people is central to healthy transition from childhood into adulthood.Citation1 Yet, in many world regions, only a few young people obtain such a critical resource for a healthy and enjoyable childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.Citation2 The gaps in access to sexuality education, health, social, and legal services is particularly wide among those at higher risk of experiencing violence and discrimination;Citation3,Citation4 in marginalised and indigenous populations;Citation5,Citation6 in those in poverty;Citation7 and in adolescents living with HIV and AIDS.Citation8 Others at risk are those with intellectual and developmental challenges;Citation9,Citation10 adolescents living in detentionCitation11,Citation12 and those with disabilities;Citation13 and adolescents living in humanitarian contexts.Citation14 Many adolescents fall into several of these intersecting categories, which makes their situation even more concerning.

This is beginning to change in terms of both increased access to sexual and reproductive health interventions and the corresponding impacts on health outcomes such as child marriage, adolescent childbearing, and female genital mutilation.Citation15 Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE), which is at the interface of health and education,Citation16 is a potent tool among other interventions to accelerate these gains further. Yet, the benefits of CSE may not be widespread if programmes do not extend to the most vulnerable and left-behind adolescents, especially those out of school, or if they are not implemented with sufficient intensity and fidelity to proven criteria for success. Similarly, the richness and impact of CSE programmes – in and out of school – hinges strongly on the quality and quantity of effort spent on preparing teachers/facilitators both pre- and in-service.Citation17,Citation18

In this paper, we report on findings of two preparatory activities undertaken towards intervention research to determine whether the activities used to train and support facilitators are feasible, appropriate, acceptable, and effective in enabling the facilitators to engage young people, deliver CSE to them in the out-of-school context, and assist them in obtaining relevant services. The first activity was a mapping of out-of-school CSE programmes targeting all or any group of adolescents/young people, implemented in Ghana between 2015 and 2020. The objective was to appreciate the depth and reach of programmes with respect to groups of adolescents targeted. We also took interest in ascertaining whether these interventions aimed at building the capacity of facilitators. Following this, we conducted a sexuality education needs assessment of young people living with HIV and AIDS (YPLHIV) and young people living in detention (YPiD) to feed back into the curriculum for intervention for these two groups.

Context of out-of-school CSE programmes in Ghana

While the nomenclature of sexuality education is a recent phenomenon in Ghana, it is not a completely new field of study/enquiry. Some of the contents of current sexuality education curriculum have been taught to children and adolescents through formal and informal means in most parts of the world.Citation19 Until the introduction of formal education in Ghana, the teaching of sexuality through informal structures often coincided with entry into puberty or menarche. The focus was biased towards girls, who were taught topics and concepts such as personal and sexual health hygiene, mostly in preparation for marriage.Citation20 In Uganda, for instance, Sylvia TamaleCitation21 discusses the practice of paternal aunties coaching adolescents on the proper sexual behaviour of girls (e.g. how to sit, walk and conduct themselves generally) and the ritual of “visiting the bush”, a practice of self-stretching the inner labia in preparation for marriage. Among boys, however, sexuality education mostly emphasised male sexual virility, the male provider role, and sexual offences, among others. The delivery of such lessons was gender-specific: women to girls and men to boys.Citation22,Citation23

The provision and delivery of different elements of sexuality education has evolved depending on the prevailing sexual and reproductive health concerns. For instance, the Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) pioneered some form of sexuality education, focusing on family planning and contraceptive use, in the late 1960s through 1980s. HIV and AIDS education and campaigns using infotainment in school and out-of-school settings characterised the 1990s through the early 2000s. This period marked widespread involvement of many other non-governmental organisations (NGOs), community-based organisations (CBOs), civil society organisations (CSOs) and faith-based organisations (FBOs) in spearheading HIV and other sexual transmitted infection (STI) mass education programmes. These took place mainly in out-of-school settings. Recent evidence shows that some out-of-school CSE interventions in Ghana are being delivered using a mix of approaches such as mHealthCitation24 and in-person facilitator/teacher-led, with pedagogies such as group discussion, role-plays, and demonstrations. For out-of-school CSE, trained peers, health workers, and in-house facilitators of NGOs/CSOs/FBOs usually teach topics with meetings held weekly or every other week.Citation25,Citation26 Other interventions are through edutainment broadcasted on public and private radio stations.Citation27 One of the challenges in out-of-school sexuality education programmes is sustainability, due to heavy reliance on external funding.Citation28 Like in-school programmes, out-of-school programmes tend to treat all children and adolescents as homogenous. Yet several sub-groups of children and adolescents have sexuality education needs which may not be prioritised in generic programmes. For instance, evidence shows that HIV and AIDS education tends to be heavily positioned towards risk reduction, without due emphasis on positive living to serve the needs of children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS.Citation29

Over the years, diverse school curricula have covered different topics of CSE. An explicit recognition of CSE emerged in the 2013 National HIV and AIDS, STI Policy as one approach to reducing new HIV infections among children and adolescents and young people.Citation30 In 2019, the Ghana Education Service published National Guidelines for Comprehensive Sexual and Reproductive Health Education in Ghana for in-school and out-of-school CSE programmes. However, the proposed guidelines were recalled due to a strong and unceasing public backlash over claims the CSE was the “Trojan Horse” to usher the country into accepting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LGBTQI) expressions, and identities.Citation31 A thorough review of in-school sexuality education in Ghana is provided elsewhere.Citation30

Young people living with HIV and AIDS and young people living in detention

In 2021, there were an estimated 1.7 million (1.2 million–2.2 million) adolescents living with HIV globally, and approximately 170,000 new HIV infections among adolescents aged 10–19 years.Citation32 In Ghana, new infections among young people aged 15–24 years stood at 5532 (∼28% of all new infections) and girls and young women constituted the highest proportion (79%) of young people with new infections.Citation33 The main routes of infection for children and young people are perinatally (around the time of birth and breastfeeding, about 70% of cases) and through unprotected sex, sexual violence, and sharing drug-injecting objects. Even though YPLHIV who were infected perinatally and those infected at a later stage share similarities, they have different needs and experiences.Citation34 Apart from the physical health challenges (development delays, tuberculosis co-infection) of children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS, they face substantial mental health problems (e.g. anxiety and depression), stigma, and discrimination. Coupled with the strong and complex emotional changes characterising adolescence, including decisions and choices on sexual and reproductive health, children, and YPLHIV, like all other children, deserve education, including that on sexuality.Citation29

Some available estimates suggest that around one million children and young people are imprisoned around the world, likely an under-estimated number, nonetheless.Citation35 Most children in detention are victims of intersectional vulnerabilities, including poverty,Citation36 dysfunctional family structures [e.g. parental criminal record/incarceration],Citation37 violence and trauma,Citation38 weak academic and learning problems or low educational aspirations,Citation39 mental health problems,Citation40 and inhabiting insecure neighbourhoods,Citation41 among others. For most incarcerated children and adolescents, interruption to schooling and other skills training programmes could entrench deviant behaviours. Evidence documents substantial effects of correctional education on reducing recidivism.Citation42 For adolescents in detention, CSE may provide considerable benefits to minimising re-entry, as some of the crimes leading to incarceration are associated with drug use and sexual violence, issues that are central to the CSE curriculum.Citation43

While our focus is on YPLHIV and YPiD, we also recognise that there are other vulnerable groups of young people who are not currently targeted. Given the near-absence of targeted sexuality education programmes for other equally vulnerable groups of young people for whom it is often difficult to attend school, this work will contribute to the emerging global effort to documenting the feasibility, accessibility, and effectiveness of intervention packages to prepare and support facilitators to deliver CSE to young people in an out-of-school context. It forms part of strategies to disseminate, adapt and apply the International Technical and Programmatic Guidance on Out-of-School CSE,Citation16 corollary to the International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education of UNESCO and other UN agencies.Citation43

Methods

The preparatory work carried out prior to our implementation research included: (1) mapping of CSE programmes in Ghana between 2015 and 2020; and (2) carrying out needs assessments with YPLHIV and YPiD.

The mapping included CSE and/or sexual and reproductive health education interventions targeted at young people aged 10–24 years that were ongoing between 2015 and 2020. Interventions that started before 2015 but were ongoing at the time of the documentation were eligible. We set 2020 as the cut-off point because our intervention kicked off in 2020. The methodology adopted for the mapping exercise comprised a documentary review (e.g. annual and project reports) supplemented with formal and informal conversations with governmental and non-governmental actors in the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) field. At the governmental level, we consulted with the National Population Council and the Ghana Health Service Family Health Division. These are two primary governmental coordinating units for out-of-school interventions on CSE. Among the non-governmental actors, we relied on information publicly available on institutional websites. Where the information available was not adequate to answer the research questions, email and phone communications were initiated with programme staff. The mapping aimed to identify types and nature of interventions being implemented, the primary and secondary beneficiaries, parts/regions of the country where interventions have been implemented, the organisations involved, model of delivery and what lessons could be drawn for our proposed intervention.

The second arm is based on needs assessment with the targeted beneficiaries, collecting primary qualitative data to inform the design, development, and implementation of the package of interventions related to information and education and health services delivery. Specifically, assessment allowed us to appreciate some of the pertinent information and education and service gaps of the targeted young people and the underlying sociocultural contexts, which CSE programmes seek to challenge by providing scientifically accurate educational content. In pursuit of these objectives, we worked with young people to define, analyse, and identify solutions that are important to them.

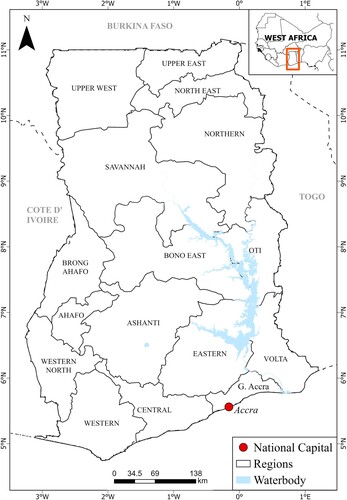

The main inclusion criteria were being either a young person in detention, and/or a young person living with HIV. Those young people in detention with less than three months to discharge from the prison were excluded, as were young people living with HIV who were less than 10 years old. The YPLHIV were recruited in Kumasi while the YPiD were recruited from the only prison for young people in Accra. is a map of Ghana showing the study sites.

A semi-structured data collection instrument was used for the two participating groups. The detention centre did not allow one-on-one interview with inmates due to security considerations. Audio recording was not allowed either, thus the research team took notes of the discussions. Interviews with YPLHIV were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were conducted by two young researchers (one female, one male). Focus group discussions (FGDs) with YPiD were conducted in the chapel of the detention centre. Some centre staff were in the hall but were not within earshot of the discussion. Their presence was not intended to interfere with the discussion but was standard security practice. Each FGD session lasted approximately 60 minutes. A mix of English and Twi (the dominant Ghanaian language) was used.

All the transcripts were analysed based on a thematic framework analysis. The first phase of the analysis involved independent reading of the transcripts and fieldnotes by authors JAA, AY, and BA. In the next phase, two coders (JAA & BA) identified preliminary themes which were recorded as separate MS Word files. The two coders then compared and discussed the themes to identify commonalities and differences with the lead author. Afterwards, the themes were reviewed for coherence and consistency. The draft report was presented to the participants for validation. The participants provided feedback on the recommendations and proposed possible interventions to help improve their access to SRHR services, including education. The protocol for the intervention research was reviewed and approved by the Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee (GHS-ERC 007/08/20 – 9th October 2020).

Findings

Three focus group discussions (FGDs) with a total of 30 male YPiD took place in the Senior Correctional Center (SCC), which is for boys only, and in-depth interviews were carried out with 10 YPLHIV (females = 7; males = 3) aged 13–24 years. Data collection took place in November 2020.

Mapping of interventions

This mapping exercise sought to answer questions regarding the kind/types, beneficiaries, geographical scope, timing, organisations involved, and delivery models of interventions between 2015 and 2020, and draw out learnings for future interventions. The ultimate outcome of all the interventions/programmes mapped is improved SRHR of young people in the zones of influence. presents the programmes/interventions identified for the period in review. Out of the 29 programmes/interventions identified, 18 (∼62%) were ongoing; the remainder had been completed between 2015 and 2019.

Table 1. SRHR Programmes for adolescents in Ghana

From the review, most CSE-related programmes/interventions being implemented in the country were geared towards improving the depth of information and knowledge available to adolescents on a range of SRHR content. In many instances, the overarching goals/aims of the programmes identified were to provide adolescents and young people with the information, education and skills to make informed choices on sexual and reproductive health. The content of such programmes covers issues such as decision-making skills, and sexual and reproductive health rights against harmful practices (e.g. early marriage). To enhance acceptance of the interventions, programmes deployed targeted advocacy strategies for buy-in among community leaders and other gatekeepers. We also note that a few of the projects complement information and education interventions with empowerment/life skills activities to advance the financial independence of young women. This is characteristic of out-of-school programmes. Programmes that have life skills complementing CSE rest on the assumption that certain reproductive health practices (e.g. transactional sex) are linked to lack of economic empowerment (see Stobenau et al.Citation44). A common feature of in-school and out-of-school CSE programmes is in-service/capacity training for teachers/facilitators. This affirms the importance of the facilitator in achieving what sexuality education should offer learners.

Almost all the interventions identified reached young people aged 10–24 years or adolescents aged 10–19 years, with most programmes focusing on the former group. One intervention focused on adolescents 15–19 years and one on young adults 20–24 years. One programme also had teachers and one had community gatekeepers as the primary beneficiaries, with adolescents and young people as secondary beneficiaries.

Many current and past interventions/programmes are localised; only one project reported being national in scope. Most interventions are in the northern part of the country, with few in central and southern Ghana. None of the interventions focused on any specific vulnerable group of young people; instead, they treated young people as a homogenous group.

The duration of ongoing and completed programmes ranges from three months to 12 years as of April 2020. Most of the projects are implemented for an average of about three years with a high number of ongoing projects expected to end in 2020. The relatively short duration of programmes may be linked to the fact that programmes are largely driven by availability of donor funds, which are usually earmarked for a specific length of time. The implementing organisations are generally local NGOs whose operations are localised. For instance, Savannah Signatures operates largely in the Northern, Northeast, Upper East, and Volta regions, while the operations of Youth Harvest Foundation are concentrated extensively in the Upper East region. However, Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) works countrywide with zonal offices in Tamale (Northern), Kumasi (Ashanti), and Accra (Greater Accra). The local nature of the implementing organisations also partially explains why coverage of interventions tends to be localised.

Three main delivery models are being used for CSE by these organisations: classroom learning (facilitator-led learning for out-of-school youths and teacher-led for in-school); mass media communication in the form of edutainment; and ICT-based delivery (SMS, interactive live social media – e.g. Facebook & Twitter). Advocacy is tailored for key community leaders (e.g. chiefs, religious leaders) and institutional heads (e.g. the Ghana Education Service and Ghana Health Service). Apart from PPAG, which runs reproductive health clinics together with information and education, all the others refer young people to public health facilities for SRHR services.

Needs of young people living with HIV and AIDS

The major needs that emerged from the interviews with YPLHIV centred on knowledge on positive living, skills in disclosure, and use of HIV and AIDS health services. A recurrent thread in the narratives was the need for skills in dealing with stigmatisation and discrimination.

Positive living

From the interview with the YPLHIV, we noted that a critical educational need was coping and healthy living after diagnosis or after being informed of their status by primary caregivers for those who acquired HIV through mother-to-child transmission. It was noted that a major reason that discouraged many YPLHIV to utilise health services and adhere to treatment was a feeling of hopelessness after being diagnosed or informed of having HIV and AIDS. Some contemplated abandoning their various life pursuits (e.g. education and apprenticeship training programmes) and in extreme situations, had suicidal ideations. These young people thought of the disease as meaning imminent death and therefore there being no need to waste effort and resources.

“A program that builds our confidence and provides us with hope is a need. Some of my YPLHIV friends and myself are sometimes worried about the future and whether it even makes sense to spend time going to school or enrolling in a skills training programme.” (Female YPLHIV, Kumasi, 20 years)

Skill in disclosing status

Another gap in their knowledge that YPLHIV indicated was how to go about status disclosure. Participants believed that they deserve acceptance in their homes and communities, but that it becomes challenging for other people to relate to them as expected when their status becomes a subject of rumour in their immediate networks. In the view of the participants, being able to disclose their status will enhance a better appreciation of the disease among individuals in their network and, most importantly, negative prospective partners. To them, the rumours about their status only worsen the myths and misconceptions and eventually, stigmatisation and discrimination.

“I think there are some things lacking. For instance, I want to know more about how I can disclose my status to a guy who is negative, and I want to have a sexual relationship with. Currently, the CSE programme does not go into details about disclosing your status to your lover or someone you want to marry. So, I think that going forward, the programme should focus on that aspect too.” (Girl YPLHIV, 21 years)

Use of health services

In the interviews with YPLHIV, one of the repeated concerns was widespread use of health services, particularly HIV and AIDS treatment services. The stories indicated that there were many adolescents and YPLHIV who did not have access to health services and therefore were not on treatment. There were also accounts of YPLHIV who did not utilise health services, specifically, anti-retroviral treatment, for two main reasons. The first was that many YPLHIV, especially those who acquired HIV and AIDS vertically, sometimes did not know their status as caregivers had not disclosed this, or the reasons for the daily medications. Secondly, among YPLHIV, there was a certain level of dissatisfaction with the adequacy and quality of information and education health care providers deliver. Their source of discontent hinged on health workers’ limited time in addressing their concerns. However, YPLHIV also pointed to high levels of satisfaction with information and education from peer educators/facilitators. To them, YPLHIV peer facilitators could be trusted and empathetic due to similarities in experiences. Accordingly, they called for education and skills to navigate the pervasive stigma around them.

Needs of young people living in detention

Here, recurrent views of YPiD about their educational and information needs are presented. While this is not an exhaustive presentation of all the discussion points, those discussed below were pervasive in all three FGDs and were considered relevant to the planned intervention.

Personal hygiene

In our discussions with the YPiD, several of them mentioned the need for education on personal hygiene. The communal living arrangements in the detention centre meant that inmates shared several spaces such as toilets and bathrooms. Participants also discussed the relatively crowded dormitories they occupied. Participants felt the need for maintaining proper personal hygiene to make life in detention manageable. According to participants, however, some inmates lacked both knowledge and consumables to maintain personal/body hygiene. In effect, a programme that emphasised personal and body hygiene was critical to making communal living bearable. A participant intimated:

“You see, as we are here, some of the boys do not like bathing; some can wear their boxer shorts (underpants) for more than three days without washing. Since we’re all sharing dormitory, such practices can affect all the roommates. We must be educated on the benefits of keeping ourselves and environment neat. Personal hygiene is not only for girls; boys must also be clean and neat.” (Male FGD Participant, 19 years, Accra SCC)

Consent in sexual relationships

Another unanimous concern of YPiD was sexual relationships and sexual consent. Many participants had personal experiences or first-hand knowledge of peers in and out of the detention centre who had engaged in sexual activities devoid of consent and with minors. Some were in the detention centre for crimes related to defilement and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). According to such participants, they became aware of the criminality of SGBV during court proceedings and if they had known previously, they would have been more cautious in the decisions and actions they took. One participant recalled:

“I am here because I raped someone who was less than 16 years. It was during the court proceeding that the judge told me that having sex with a person – boy or girl below 16 years was a criminal offence. It was not my first time, so the judge sentenced me here. If I had the education and information, maybe I would not have done it.” (Male FGD Participant, 17 years, Accra SCC)

“If my girl comes to my house and she did not give me (sex) and I just force her small, is there anything wrong with that?” (Male FGD Participant, 18 years Accra SCC)

Sexuality education delivery model

The YPiDs also shared some perspectives on the channel/medium of delivering the sexuality education programme. The narratives showed that they currently relied on TV programmes for sexuality education. This, in their view, was unsuitable as it lacked mechanisms for in-person interactions (e.g. asking questions and seeking clarifications). While admitting that they received some education on sexual and reproductive health from health care providers and wardens at the detention centre intermittently, it was inadequate and mostly ad hoc. Often, information and education were provided to individuals in response to some health incidents. There were therefore no deliberate and regular educational programmes that focused on reproduction and sexuality. While some of the inmates who had spent longer periods in the correctional centre recalled some past CSE-related programmes, they questioned the appropriateness of the delivery mechanism. According to some of the beneficiaries in our assessment group, the use of peers as facilitators created mistrust among inmates. They recounted that beneficiary inmates did not feel comfortable interacting with their peers, particularly on sensitive SRHR questions; they feared that peer facilitators could reveal their concerns to the Centre’s authorities, leading to punishments or stigmatisation. There were particular fears in relation to peer facilitators disclosing confidential information to wardens on questions around same-sex relationships.

Propriety and health implications of same-sex sexual intercourse

Situational homosexualityCitation45,Citation46 is a well-documented phenomenon among people who are immersed in single-sex environments (e.g. boarding schools, military camps, correctional institutions). Individuals who find themselves in such situations may identify as heterosexual, but are temporarily satisfying a deprivation and will return to heterosexual activities when removed from confinement.Citation47 YPiD who participated in the study asked questions and desired to know/learn more about the propriety (e.g. health, social acceptability) of same-sex sexual intercourse. Even though none of the participants openly admitted having had or being approached to engage in homosexual activities, the fact that it came up in the discussion may indicate the presence of the practice in the Center and therefore the need to know more about any implications of the practice. It is noteworthy that these questions were asked although there were prison wardens within the discussion venue.

Cross-cutting need – stigmatisation

The narratives of YPLHIV and YPiD revealed strong concerns about stigmatisation and discrimination. Whereas the YPLHIV discussed present/current experiences of stigmatisation and how to navigate about this, the YPiDs were worried about future threats they imagined. Either way, the central theme is about overcoming stigma and being able to participate in routine social life. According to YPLHIV, their daily lives were characterised by pervasive stigmatisation and discrimination due to the disease. For some, it was seriously felt at the household level and among household members. Some adolescents reported that other parents who knew their status had cautioned their children against playing with them. Unfortunately for them, the health system/service was usually focused on treatment and even when education was provided, it was scanty. Some were constantly questioned about how they got infected, making some family members stigmatise and discriminate against them. One participant illustrated:

“When I was very sick, my mother will put my food on the floor and kick it to me with her slippers. She told my children that they will die if they eat with me. My first child did not mind but my second daughter will insult me and laugh at me.” (Female FGD participant, Kumasi)

The stigma went beyond families and communities to some health professionals. Some participants recalled being questioned, blamed, and reprimanded for being HIV positive by health providers and some providers disclosed the participant’s status to some relations without their consent.

“For me the nurse I met killed my hopes. Whenever I go to her, she will say, ‘how can a 16-year-old girl like me be HIV positive?’”. (Female FGD participant, Kumasi)

For the incarcerated young people, the “tag” of being a former prisoner was a recurrent concern. They constantly imagined the extent to which they would be stigmatised and avoided by both family and friends. Among this group, the possibility of being perceived as a persisting threat on account of the crimes that led to detention was concerning. To both group of participants, an educational programme for them should include building resilience and offering the intellectual and emotional skills to deal with the pervasive stigmatisation.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was two-fold: first, to map completed or ongoing CSE-related interventions for out-of-school young people in Ghana, covering 2015 to 2022. Specifically, the study sought to understand the spread and coverage of CSE interventions for the targeted populations. The results showed that many disparate and short interventions have been implemented in the last decade, but these were predominantly concentrated in the northern part of the country. The second objective aimed at discussing prevalent sexuality education needs of two vulnerable out-of-school populations: YPLHIV, and those in detention centres. The sexuality education needs assessment of the two targeted groups revealed unique concerns among YPLHIV (e.g. positive living, skills in status disclosure, use of health services) and YPiD (personal hygiene, sexual consent, programme delivery model, and same-sex sexual activities) as well as a cross-cutting concern on stigmatisation and discrimination. Importantly, all the needs described are related to current standards/guidelines on CSE which makes it feasible for our interventions to be easily adapted/adopted to suit the needs of targeted populations.

The mapping revealed several ongoing and completed interventions to provide different iterations of CSE for adolescents and young people, especially those out of school. However, these interventions revealed geographical imbalances: they were concentrated in northern Ghana and tended to be at the population level without specific segmentation, i.e. deliberate focus on specific groups of vulnerable young people. This may be because, at the population level, SRHR problems of young people in Ghana tend to assume a geographical character. For instance, in the northern regions (i.e. Upper East, Upper West, Northern, North East, and Savannah) child marriage and female genital mutilation are more prevalent than in the middle and southern regions.Citation48 Conversely, teenage pregnancy is more likely to be reported in the Bono East, Bono or Ahafo and Volta regions compared to other regions. The adolescent fertility rate, however, is lowest in Greater Accra.Citation49,Citation50 Commercial sexual exploitation is more likely in Central Region (Cape Coast specifically) and Accra compared to the other regions.Citation51 Perhaps it is within this context that interventions are dispersed across regions, most likely based on local realities. The appeal of the northern regions to NGOs could be linked to their unfavourable standing on other socioeconomic indicators: they record the highest rates of poverty.Citation52 High rates of school dropout and generally low levels of education, with limited access to health services, particularly SRH services, are coupled with strong religious and traditional norms that can impede better realisation of SRHR.Citation53,Citation54 These varied contexts may be contributing to the northern focus in SRHR interventions. Practically, the findings concerning geographical differences highlight the importance of a needs-based approach in implementing out-of-school CSE interventions, that is, tailoring CSE interventions to meet the needs of specific vulnerable populations, rather than generic population-level interventions.

As earlier suggested, YPLHIV face peculiar challenges in traversing the realities of being infected with a chronic health condition, especially in contexts where the major channel of HIV infection is heterosexual, and young people are “expected” not to be sexually active.Citation55,Citation56 The implication is that such young people may be doubly stigmatised on two levels: (a) being perceived as promiscuous and engaging in “illicit” sex, and (b) as receiving the consequences they deserve in the form of HIV. Such hostile environments worsen the wellbeing of adolescents living with HIV and AIDS, largely because – whether acquired vertically or horizontally – HIV diagnosis during adolescence coincides with the time adolescents are forming personal identities and getting to know themselves. The diagnosis complicates their sense of worth and questioning of sexual rights and responsibilities. The same concern emerged for the YPiD: the fear of stigmatisation after release was a persistent subject of importance in all three group discussions. The complexities of the adolescence stage on its own, coupled with living with a stigmatised disease or becoming a prisoner at an early stage, provide a justification for targeting these young people with CSE, which has a potential of improving their life skills in dealing with adversities.

The findings also bring to bear the question of relevance of peer education/facilitation in sexuality education programmes. Two contrasting views about peer education emerge in this study. On the one hand, YPiD have major reservations about peers being capable and appropriate for the delivery of sexuality education, including answering questions on sensitive SRHR matters that may require further clarification. The topmost concern was on same-sex sexual relationships, which are currently viewed as unnatural and as a “criminal” act in Ghana.Citation57 On the other hand, YPLHIV expressed confidence in peer facilitation, in their case peers who are also living with HIV and AIDS. The general feeling was that peer YPLHIV could relate and share more personal experiences on dealing with reproductive and sexual health and education concerns. Generally, the evidence on peer education on SRHR outcomes is mixed.Citation58 Whereas some studies conclude that the benefits are often exclusive to peer educators,Citation59,Citation60 others find evidence to the contrary.Citation61,Citation62 It is apparent that for out-of-school programmes that have flexibility, learners should play a critical role in defining their preferred facilitators to stimulate the necessary outcomes. This is important in the sense that different groups of learners have diverse needs and without their preferences being duly considered, programmes may not achieve the intended objectives. As Siddiqui et al assert,Citation58 peer education still has a place in SRHR interventions when properly suited to its audience.

Another finding worth considering in this and other future interventions concerns the channel of delivering CSE and related content. For the YPiD, there is a premium in in-person delivery of CSE, given that previous sessions that utilised media outlets (e.g. radio and TV) did not offer opportunities for in-person interactions. In-person delivery was preferred. While the use of the media in mass education reaches a wider audience and offers some positive changes or minimising incidence of negative behaviours,Citation63 the opportunities for one-on-one interactions between facilitators and learners may be limited. Learners may not fully concentrate on lessons and will have no opportunity to get clarification on perplexing questions or learn from each other’s experiences in personal and collegial spaces. For our project, the modules will be delivered in person, and we anticipate that the depth of interpersonal connection may be deeper.

Some limitations of the study are worth mentioning. One, the qualitative evidence was based on a small sample of participants from both study groups. On the mapping, we relied only on publicly available information, mainly from the websites of SRHR organisations operating in the country. While efforts were made to reach out to organisations to share information on projects/interventions within the period of interest, we might have missed some interventions, especially those run by faith-based organisations (e.g. churches) which were unlikely to be publicised on the Internet. That notwithstanding, by covering some of the key SRHR players in the country, our findings provide good assurances about the comprehensiveness of this review.

Conclusion

This paper provides insights into available programmes/interventions for young people broadly in Ghana, and some information, education, and health services need of YPLHIV and YPiD. While recognising the importance of recent and ongoing programmes, the geographical coverages of the interventions were limited and often treated young people as a homogenous group, with none focusing on building the capacity of facilitators or tutors to deliver lessons effectively. The noted distinctions in the needs of YPLHIV and YPiD highlight the importance of young people’s participation in deciding what must be considered and included in interventions intended for them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Engel DMC, Paul M, Chalasani S, et al. A package of sexual and reproductive health and rights interventions – what does it mean for adolescents? J Adol Health. 2019;65(6):S41–S50. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.014

- Yankah E. International framework for sexuality education: UNESCO’s international technical guidance. In: J Ponzetti Jr, editor. Evidence-based approaches to sexuality education: A global perspective. New York: Routledge; 2015. p. 41–56.

- Sumner SA, Mercy JA, Saul J, et al. Prevalence of sexual violence against children and use of social services – seven countries, 2007–2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(21):565.

- World Health Organization. Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused: WHO clinical guidelines; 2017.

- Gabster A, Cislaghi B, Pascale JM, et al. Sexual and reproductive health education and learning among indigenous youth of the Comarca Ngäbe-Buglé, Panama. Sex Educ. 2021;22(3):260–274.

- Kenny B, Hoban E, Pors P, et al. A qualitative exploration of the sexual and reproductive health knowledge of adolescent mothers from indigenous populations in ratanak Kiri Province, Cambodia. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(4):5240–5240. doi:10.3316/informit.139244212838981

- Chacham AS, Simão AB, Caetano AJ. Gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health among low-income youth in three Brazilian cities. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24(47):141–152. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2016.06.009

- Hamzah L, Hamlyn E. Sexual and reproductive health in HIV-positive adolescents. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13(3):230–235. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000456

- Roden RC, Schmidt EK, Holland-Hall C. Sexual health education for adolescents and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: recommendations for accessible sexual and reproductive health information. Lancet Child Adol Health. 2020;4(9):699–708. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30098-5

- Stein S, Kohut T, Dillenburger K. The importance of sexuality education for children with and without intellectual disabilities: what parents think. Sex Disabil. 2018;36(2):141–148. doi:10.1007/s11195-017-9513-9

- Johnston EE, Argueza BR, Graham C, et al. In their own voices: the reproductive health care experiences of detained adolescent girls. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26(1):48–54. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.009

- Thompson M, Davis L, Pendleton V, et al. Differences in sexual health outcomes between adolescents in public schools and Juvenile correctional facilities. J Correct Health Care. 2020;26(4):327–337. doi:10.1177/1078345820953405

- Kumi-Kyereme A, Seidu A-A, Darteh EKM. Factors contributing to challenges in accessing sexual and reproductive health services among young people with disabilities in Ghana. Glob Soc Welf. 2021;8:189–198. doi:10.1007/s40609-020-00169-1

- Jennings L, George AS, Jacobs T, et al. A forgotten group during humanitarian crises: a systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people including adolescents in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2019;13:1–16. doi:10.1186/s13031-019-0240-y

- Chandra-Mouli V, Jane Ferguson B, Plesons M, et al. The political, research, programmatic, and social responses to adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights in the 25 years since the international conference on population and development. J Adol Health. 2019;65(6):S16–S40. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.011

- UNFPA. International technical and programmatic guidance on out-of-school comprehensive sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach for non-formal out-of-school programmes Vol. New York: UNFPA; 2020.

- Keogh SC, Stillman M, Leong E, et al. Measuring the quality of sexuality education implementation at the school level in low-and middle-income countries. Sex Educ. 2020;20(2):119–137. doi:10.1080/14681811.2019.1625762

- Sidze EM, Stillman M, Keogh S, et al. From paper to practice: sexuality education policies and their implementation in Kenya.; 2017

- Amo-Adjei J. Sexuality education in Ghana’s schools: some answers to ‘When’ and ‘What’; 2021.

- Anarfi JK, Owusu AY. The making of a sexual being in Ghana: the state, religion and the influence of society as agents of sexual socialization. Sex Cult. 2011;15(1):1–18. doi:10.1007/s12119-010-9078-6

- Tamale S. Eroticism, sensuality and “Women’s secrets” among the Baganda: a critical analysis. Feminist Africa. 2005;5(1):9–36.

- Hodes R, Gittings L. ‘Kasi curriculum’: what young men learn and teach about sex in a South African township. Sex Educ. 2019;19(4):436–454. doi:10.1080/14681811.2019.1606792

- Izugbara CO. Home-based sexuality education: Nigerian parents discussing sex with their children. Youth Soc. 2008;39(4):575–600. doi:10.1177/0044118X07302061

- Rokicki S, Cohen J, Salomon JA, et al. Impact of a text-messaging program on adolescent reproductive health: a cluster–randomized trial in Ghana. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):298–305. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303562

- Van der Geugten J, van Meijel B, den Uyl MH, et al. Evaluation of a sexual and reproductive health education programme: students’ knowledge, attitude and behaviour in Bolgatanga Municipality, Northern Ghana. Afr J Reprod Health. 2015;19(3):126–136.

- Yakubu I, Garmaroudi G, Sadeghi R, et al. Assessing the impact of an educational intervention program on sexual abstinence based on the health belief model amongst adolescent girls in Northern Ghana, a cluster randomised control trial. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):124. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0784-8

- Savannah Signatures. Life choices project. Vol. Tamale Savannah Signatures; 2017b.

- Savannah Signatures. The starts with me: programme outcomes for 2016. Vol. Tamale Savannah Signatures; 2017a.

- Bridges E. Young people living with HIV around the world: challenges to health and wellbeing persist. Washington, D.C.: Advocates for Youth; 2011.

- Awusabo-Asare K, Stillman M, Keogh S, et al. From paper to practice: sexuality education policies and their implementation in Ghana. New York, Guttmacher Institute; 2017.

- Ashford HR. The Christian Council, moral citizenship and sex education in Ghana, 1951–1966. Hist Educ. 2022;51(1):91–113. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2021.1918272

- UNAIDS. Unaids epidemiological estimates, 2021. Vol. New York: UNAIDS; 2021.

- Ghana AIDS Commission. Ghana’s HIV fact sheet, 2018. edited by G. A. Commission. Accra; 2018.

- STOPAIDS. Factsheet: adolescents and young people and HIV. Vol; 2016.

- Bochenek MG. Children behind bars: the global overuse of detention of children. Human Rights Watch; 2016.

- Elliott S, Reid M. Low-income Black Mothers parenting adolescents in the mass incarceration era: the long reach of criminalization. Am Sociol Rev. 2019;84(2):197–219. doi:10.1177/0003122419833386

- Poltava KO, Dubovych OV, Serebrennikova AV, et al. Juvenile offenders: reasons and characteristics of criminal behavior. Іnt J Criminol Sociol. 2020;9:1573. doi:10.6000/1929-4409.2020.09.179

- Peltonen K, Ellonen N, Pitkänen J, et al. Trauma and violent offending among adolescents: a birth cohort study. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2020;74(10):845–850. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214188

- Barnert ES, Perry R, Shetgiri R, et al. Adolescent protective and risk factors for incarceration through early adulthood. J Child Fam Stud. 2021;30:1428–1440. doi:10.1007/s10826-021-01954-y

- Fleming CM, Nurius PS. Incarceration and adversity histories: modeling life course pathways affecting behavioral health. Am J Orthopsych. 2020;90(3):312. doi:10.1037/ort0000436

- Nichols EB, Loper AB, Patrick Meyer J. Promoting educational resiliency in youth with incarcerated parents: the impact of parental incarceration, school characteristics, and connectedness on school outcomes. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(6):1090–1109. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0337-6

- McNeeley S. The effects of vocational education on recidivism and employment among individuals released before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2023: 0306624X231159886.

- UNESCO, UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women and WHO. International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach. Paris UNESCO Publishing; 2018.

- Stoebenau K, Heise L, Wamoyi J, et al. Revisiting the understanding of “Transactional sex” in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review and synthesis of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:186–197. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.023

- Hartenstein CC, Gonsiorek JC. Situational homosexuality. Int Encyclop Hum Sexual. 2015: 1115–1354. doi:10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs486

- Pierce DM. Test and nontest correlates of active and situational homosexuality. Psychol: J Hum Behav. 1973;10(4):23–26. doi:10.3149/jms.100

- Hensley C, Tewksbury R, Wright J. Exploring the dynamics of masturbation and consensual same-sex activity within a male maximum security prison. J Men’s Stud. 2001;10(1):59–71. doi:10.3149/jms.1001.59

- de Groot R, Kuunyem MY, Palermo T. Child marriage and associated outcomes in Northern Ghana: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pub Health. 2018;18(1):285. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5166-6

- Ghana Statistical Service, Ghana Health Service and ICF International. Demographic and health survey 2014. Vol. Rockville, Maryland, USA: GSS, GHS, and ICF International; 2015.

- Ghana Statistical Service, Ghana Health Service and ICF International. Ghana maternal health survey 2017. Vol. GSS, GHS, and ICF. Accra, Ghana; 2018.

- Oduro GY, Otoo S, Asiama AA. Ethical and practical challenges in researching prostitution among minors in Ghana. In: Routledge international handbook of sex industry research; 2018.

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Living Standards Survey: Ghana Statistical Service; 2018.

- Ganle JK. Why Muslim Women in Northern Ghana do not use skilled maternal healthcare services at health facilities: a qualitative study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2015;15(1):10. doi:10.1186/s12914-015-0048-9

- Moyer CA, Adongo PB, Aborigo RA, et al. “It’s up to the Woman’s People”: how social factors influence facility-based delivery in rural Northern Ghana. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(1):109–119. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1240-y

- Reis RK, Gir E. Living with the difference: the impact of serodiscordance on the affective and sexual life of HIV/aids patients. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2010;44:759–765. doi:10.1590/S0080-62342010000300030

- Wazakili M, Mpofu R, Devlieger P. Experiences and perceptions of sexuality and HIV/aids among young people with physical disabilities in a South African township: a case study. Sex Disabil. 2006;24(2):77–88. doi:10.1007/s11195-006-9006-8

- Atuguba RA. Homosexuality in Ghana: morality, law, human rights. J. Pol. & L. 2019;12:113.

- Siddiqui M, Kataria I, Watson K, et al. A systematic review of the evidence on peer education programmes for promoting the sexual and reproductive health of young people in India. Sex Reprod Health Matt. 2020;28(1):1741494. doi:10.1080/26410397.2020.1741494

- Michielsen K, Beauclair R, Delva W, et al. Effectiveness of a peer-led HIV prevention intervention in secondary schools in Rwanda: results from a non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Pub Health. 2012;12(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-729

- Swartz S, Deutsch C, Makoae M, et al. Measuring change in vulnerable adolescents: findings from a peer education evaluation in South Africa. SAHARA-J: J Soc Aspects HIV/Aids. 2012;9(4):242–254. doi:10.1080/17290376.2012.745696

- Balaji M, Andrews T, Andrew G, et al. The acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of a population-based intervention to promote youth health: an exploratory study in Goa, India. J Adol Health. 2011;48(5):453–460. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.029

- Gogoi A, Parmar S, Katoch M, et al. Addressing the reproductive health needs and rights of married adolescent couples. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21(Issue sup1):80. doi:10.3109/13625187.2016.1165961

- Le Port A, Seye M, Heckert J, et al. A community edutainment intervention for gender-based violence, sexual and reproductive health, and maternal and child health in rural Senegal: a process evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13570-6