Abstract

Sexual violence and HIV/AIDS are major public health concerns in India. By promoting bodily autonomy, wellbeing, and dignity through knowledge and skills, comprehensive sexuality education for young people can help prevent adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes. While there is increased recognition globally regarding young people’s need for sexuality education, translating this recognition into accepted programmes in India has been challenging. This scoping review aims to examine recommendations for promising practices for the design and implementation of sexuality education programmes and resources aimed at youth in India. A systematic search and review of the literature was conducted from June to August 2020. Of the total 5312 citations identified and screened, 622 advanced to full-text screening, and 39 were included in the final analysis. Promising practices include the need to: tailor content to serve the needs of the specific youth population being targeted; use engaging and participatory methods to teach sexual health content; work in partnership and collaboration with local experts and organisations; address potential barriers to participation and work to mitigate those barriers for marginalised youth; be youth friendly, flexible and convenient; and to be developmentally and culturally appropriate for the Indian youth context. Sexuality education programmes should integrate into existing community services and link with local reproductive health services to help provide youth with access to the services they may need. Continued work and efforts are required to address the interrelated and broad structural factors, including political, financial, social, and cultural factors that affect youth sexual health and wellbeing.

Résumé

La violence sexuelle et le VIH/sida sont des problèmes majeurs de santé publique en Inde. En promouvant l’autonomie corporelle, le bien-être et la dignité par le biais des connaissances et des compétences, l’éducation complète à la sexualité des jeunes peut contribuer à prévenir les effets néfastes sur leur santé sexuelle et reproductive. S’il est de plus en plus admis dans le monde que les jeunes ont besoin d’une éducation sexuelle, il s’est révélé difficile de traduire cette prise de conscience dans des programmes acceptés en Inde. Cette étude de portée vise à examiner les recommandations relatives à des pratiques prometteuses pour la conception et la mise en œuvre de programmes et de ressources d’éducation sexuelle à l’intention des jeunes en Inde. Une recherche et un examen systématiques des publications ont été menés entre juin et août 2020. Sur les 5312 citations totales identifiées et examinées, 622 sont parvenues à l’examen du texte intégral et 39 ont été incluses dans l’analyse finale. Parmi les pratiques prometteuses, il convient de citer la nécessité: d’adapter le contenu pour répondre aux besoins de la population de jeunes spécifique visée; d’utiliser des méthodes engageantes et participatives pour enseigner le contenu relatif à la santé sexuelle; de travailler en partenariat et en collaboration avec des organisations et experts locaux; d’éliminer les obstacles potentiels à la participation et de s’employer à atténuer ces obstacles pour les jeunes marginalisés; d’être adaptées aux jeunes, souples et pratiques; et d’être appropriées du point de vue du développement et de la culture au circonstances de la jeunesse indienne. Les programmes d’éducation à la sexualité doivent s’intégrer dans les services communautaires existants et établir des liens avec les services locaux de santé reproductive pour aider à fournir aux jeunes l’accès aux services dont ils peuvent avoir besoin. Il faut poursuivre le travail et les activités afin de traiter les facteurs structurels d’ensemble interdépendants, notamment de nature politique, financière, sociale et culturelle, qui influent sur la santé et le bien-être sexuels des jeunes.

Resumen

La violencia sexual y el VIH/SIDA son graves problemas de salud pública en India. Al promover la autonomía corporal, el bienestar y la dignidad por medio de conocimientos y habilidades, la educación integral en sexualidad para las personas jóvenes puede ser útil para evitar los resultados adversos de la salud sexual y reproductiva. Aunque cada vez hay más reconocimiento a nivel mundial de la necesidad de las personas jóvenes de recibir educación en sexualidad, ha sido un reto traducir este reconocimiento a programas aceptados en India. Esta revisión de alcance pretende examinar las recomendaciones de prácticas prometedoras para el diseño y la ejecución de programas de educación en sexualidad y recursos dirigidos a jóvenes en India. Entre junio y agosto de 2020, se realizó una búsqueda y revisión sistemáticas de la literatura. Del total de 5312 citas identificadas e investigadas, 622 avanzaron a la revisión del texto completo y 39 se incluyeron en el análisis final. Entre las prácticas prometedoras se encuentran la necesidad de: adaptar el contenido para atender las necesidades de la población específica de jóvenes bajo estudio; utilizar métodos interesantes y participativos para enseñar contenido sobre salud sexual; trabajar en alianza y colaboración con expertos y organizaciones locales; abordar las posibles barreras a la participación y trabajar para mitigar esas barreras para jóvenes marginados; tener en cuenta las necesidades de la juventud y ser flexible y conveniente; y ser adecuado para el desarrollo y la cultural del contexto de la juventud de India. Los programas de educación en sexualidad deben integrarse en los servicios comunitarios existentes y vincularse con los servicios locales de salud reproductiva para ayudar a proporcionar a la juventud acceso a los servicios que podrían necesitar. Es imperativo continuar el trabajo y los esfuerzos por abordar los factores interrelacionados y estructurales generales, entre ellos factores políticos, financieros, sociales y culturales, que afectan la salud sexual y el bienestar de las personas jóvenes.

Introduction

Properly-designed and properly-executed comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) programmes and resources for youth are an important component in sexual health promotion and in public health efforts to combat the global AIDS epidemic.Citation1 CSE “imparts critical information and skills for life. These not only include knowledge on pregnancy prevention and safe sex, but also understanding bodies and boundaries, relationships and respect, diversity and consent” (p. 7).Citation1 CSE has a positive impact on sexual and reproductive health, notably in contributing to reducing rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV/AIDS and unintended pregnancies.Citation1 Contrary to popular myths, it does not hasten the onset of sexual activity in youth but rather has a positive impact by promoting the adoption of safer sexual behaviours and can even delay sexual debut.Citation2,Citation3 A 2014 review of school-based sexuality education programmes found that students demonstrated increased HIV knowledge, increased self-efficacy related to refusing sexual activities, increased contraception and condom use, a lower number of sexual partners and delayed onset of sexual activity and intercourse.Citation4 CSE is also important for effectively addressing issues such as sexual and gender-based violence, gender-based discrimination, as well as homophobia/ transphobia.Citation3 In addition to individual and population health, CSE is integral to the human rights upheld in United Nations instruments including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,Citation5 the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women,Citation6 and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.Citation7 Comprehensive sexuality education:

“… enables young people to protect and advocate for their health, well-being and dignity by providing them with a necessary toolkit of knowledge, attitudes and skills. It is a precondition for exercising full bodily autonomy, which requires not only the right to make choices about one’s body but also the information to make these choices in a meaningful way.”Citation8

This scoping review aims to examine recommendations for promising practices for the design and implementation of sexuality education programmes and resources aimed at youth in India.

Sexual and reproductive health in India

India has the third largest HIV epidemic in the world, with over 2.1 million people living with HIV.Citation12 The epidemic is concentrated among key affected populations, including sex workers, men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, transgender people, migrant workers, and truck drivers.Citation12 However, other strata of society are also affected. Notably, rates are growing among married, monogamous, heterosexual women who are infected by their husbands engaging in extramarital or paid sex; in this regard, there is a noted intersection with intimate partner violence.Citation13 HIV incidence, prevalence and AIDS-related death rates remain among the highest in the world, and a number of issues limit further progress, including HIV-linked stigma, low levels of education regarding HIV among people living with the illness, limited awareness about sexual health and prevention of HIV, and limited awareness regarding freely available antiretroviral therapies.Citation14

Sexual violence is also a prevalent issue in India, especially rape and sexual violence against women.Citation15 According to UN Women, 35% of women worldwide have experienced either physical or sexual violence at some point in their lives.Citation15 However, this value increases dramatically across various states in India, reaching a staggering 88.95% in certain areas.Citation15–17 In concert with patriarchal gender norms, the effective lack of open discussion in Indian society about healthy sexuality, consent in sexual activity, and sexual assault contributes to these overwhelming numbers.Citation16,Citation17

Adolescent pregnancy and its consequences also present a major challenge. Pregnancy at an early age can put both the mother and the baby at risk for many related health complications.Citation18,Citation19 The social consequences of adolescent pregnancy can include dropping out of school, lower educational attainment, decreased social and employment opportunities, reduced lifetime earnings, and even violence via suicide or homicide in some cases.Citation18 The WHO Guidelines on Preventing Early Pregnancy and Poor Reproductive Outcomes Among Adolescents in Developing Countries highlights the key role of sexuality education in achieving its goals.Citation20

Comprehensive sexuality education and the Indian context

India was a signatory to the Programme of Action (PoA) of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) where the sexual and reproductive health needs of youth as a group were officially articulated and identified as an area for further action. The PoA from the ICPD states in paragraph 7.47: “Governments, in collaboration with non-governmental organizations, are urged to meet the special needs of adolescents and to establish appropriate programmes to respond to those needs.”Citation21 India’s efforts to operationalise the PoA began with the launching of the Reproductive and Child Health Programme in 1997. In 2000, adolescent reproductive and sexual health was recognised as a top priority in the National Population Policy of 2000 and in the Reproductive and Child Health II programme of 2005.Citation22

In India, a two-pronged approach is being used to implement sexuality education. For youth that are currently enrolled in school, the national Adolescent Education Programme (AEP) is being delivered in school, reaching students between the ages of 13-18.Citation23 The AEP was launched in 2005 by the Ministry of Human Resource Development and the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO).Citation23 The AEP seeks to provide accurate, age-appropriate and culturally-relevant information regarding sexual health, gender, sexuality, communication skills, and navigating relationships. Unfortunately, serious reservations have been expressed in India about the sexuality component of the programme.Citation24 Following the pushback, efforts were made by several stakeholders, including governmental departments, the NACO, the National Council of Educational Research, and civil society organisations, to review the original curriculum and generate support for the implementation of the programme in general. They provided states flexibility to modify the existing curriculum if necessary, while reiterating the need to keep the AEP overall.Citation23 The revised curriculum consisted of four sections: (a) changes from childhood to adolescence; (b) adolescent reproductive and sexual health; (c) mental health and substance misuse; and (d) life skills and HIV prevention.Citation23 The AEP has been widely implemented in high schools in partnership with state and national educational organisations as well as civil society organisations.Citation23

There are other programmes that have been designed to provide sexual health education to youth, including the School Health Programme under the National Rural Health Mission; Red Ribbon Clubs under the National AIDS Control Project; the University Talk AIDS Program; the Youth Unite for Victory on AIDS campaign; and Yuva, which is a network of seven youth organisations working to provide youth with sexual health education and life skills training in partnership with the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports and NACO.Citation23

There is no formal programme for educating youth that are not enrolled in school, but information and counselling are available through the adolescent health clinics created through the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health initiative.Citation1 There are also several key programmes run by the National AIDS Control Program and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, including the Village Talk AIDS Program which is an educational programme designed for out-of-school youth; Red Ribbon Clubs which serve to provide counselling, life skills training, and recreational activities; awareness campaigns and counselling through Accredited Social Health Activists; and teen clubs to provide youth with life skills experiential learning and education on reproductive and sexual health.Citation23,Citation25 In 2014, the Government of India started a national programme entitled “Rashtriya Kishor Swathya Karyakram.” The aim of the programme is to expand outreach to youth and their communities, especially the most vulnerable and at-risk, including adolescents not enrolled in schools. The programme includes the establishment of adolescent-friendly health clinics, nutritional supplementation, peer education programmes, and menstrual product provision.Citation26

The reach and the quality of sexuality education programmes, however, are questionable. Open discussion of sexuality remains largely taboo in India, due partially to Victorian-era mores inserted into society during British colonial rule. In the present day, conservative attitudes towards sexuality are framed as intrinsic to Indian cultural identity.Citation9,Citation11 As of 2019, there is a ban on the AEP in at least five states across India due to mass outrage about the notion of teaching youth about sexuality. Moreover, there is no uniformity in how the subject is approached across the country, with actual content regarding sexuality frequently diluted or absent due to parental and community concerns about teaching youth about sexuality, and due to teacher embarrassment or discomfort.Citation9,Citation11,Citation27 Generally, implementation of the AEP is uneven and reach remains limited. There is also limited follow-through, monitoring, and evaluation of adolescent health programmes across India.Citation23,Citation28,Citation29

Research question, objectives, and definitions

This research sought to answer the following question: What are promising practices for the design and implementation of sexuality education programmes aimed at youth in India?

In this research project, we engaged with a definition of “promising practices” as practices described by programmes that report successful outcomes. Promising practices are differentiated from best practices as there is not yet enough research evidence to definitively establish the practice as the standard guideline for effective implementation across all settings.Citation30

There are several articles that have assessed sexuality education programmes in other countries and even “developing countries” as a whole.Citation31–37 They advocate for and present guidelines for comprehensive sexuality education, including elements such as curricular objectives, guidance on topic inclusion, the development of activities, and the process of developing educational resources. However, in this review, the focus is on youth sexuality education programmes based out of India only. By looking at programmes carried out within the Indian context only, we hope to identify characteristics of successful programmes that are specific to the Indian setting and the youth living within this environment.

There is a myriad of micro- and macro-level upstream factors that can contribute to adverse sexual health outcomes for youth. Micro-level factors include influences on an individual level that can affect choices youth make, such as family traditions, local community norms, and economic circumstances. Macro-level factors can include regional or national norms, laws, policies, and overarching culture. Legal and regulatory frameworks can facilitate or hinder these choices and behaviours made by youth, such as the enforcement of laws concerning child marriage, harm reduction, human trafficking, sexual exploitation, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault.Citation38 Micro- and macro-levels provide a framework for understanding socioeconomic determinants of health that can impact the sexual health and overall wellbeing of youth. Each of these levels interacts with and influences the others, and they can be visualised as being linked together via a feedback loop in which changes at one level will influence events at another level.Citation39 In order to promote the wellbeing of youth, changes are required at these local, regional, and national levels by different sectors to bring about lasting improvement in outcomes and promote healthy practices.Citation18 In this review, we endeavoured to analyse the selected papers through this lens, with a focus on the social determinants and upstream factors that influence youth health, which include socioeconomic and cultural factors, as well as the characteristics of social spaces and physical environments.

In the research presented in this paper, we engaged with definitions of key constructs. We engaged with a definition of gender as the social identity that encompasses the norms, behaviours and roles with which an individual identifies. While this can correlate with biological sex assigned at birth, it does not need to. Sexual identity is defined as the romantic and/or sexual orientation that an individual identifies with.Citation40 Sexual and reproductive health refers to the state of overall physical and emotional well-being in relation to sexuality, including positive relationships free from coercion or violence.Citation20

Methods

A scoping review aims to map out key concepts and knowledge in a particular area, by looking at the “extent, range and nature” of work done, to “summarize and disseminate” what is known, and to identify gaps for further research or action. The methodological framework of Arksey and O'MalleyCitation41 was drawn upon to guide the scoping review process, based on five main stages: (a) identifying the research question, (b) identifying relevant articles, (c) article selection, (d) charting the data, and (e) summarising and analysing the results. After the focused research question was identified and developed (namely: What are promising practices for the design and implementation of sexuality education programmes aimed at youth in India?), the selected relevant articles were examined in order to analyse the field, summarise and report results, as well as identify gaps and areas for further research.

A systematic search of the literature was conducted. The inclusion criteria were articles discussing and examining programmes for youth based in India that sought to improve their reproductive and sexual health knowledge, published from the year 1995 onwards. This threshold was chosen as this year marked the landmark decision within the field to officially include youth sexual health in the ICPD’s Programme of ActionCitation21 and the subsequent signing of the Programme by India, officially marking youth sexual and reproductive health as a national area for further action. Articles published in English from peer-reviewed sources and grey literature, were included. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, COCHRANE, CINAHL, ProQuest (Sociology, Nursing & Allied Health), and Google Scholar. References of selected papers, and websites of relevant non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other groups, were also scanned to identify additional potential papers that could be included.

We used various combinations of keywords and all possible associated terms in English. The search terms are listed in . The complete search strategy is provided in the online Supplemental Material. Our search strategy was validated by a librarian from the Health Sciences Library at Queen’s University. All selected documents were saved in Covidence software.Citation42

Table 1. Search terms utilisedTable Footnotea

The initial search process picked up many duplicates, reinforcing the completeness of the search. To add to the rigour of the search strategy, two reviewers independently conducted an initial title-abstract screening of all articles; results were compared and any discrepancies were reviewed to derive a clear and reproducible protocol. All articles that passed this screening moved onto full-paper screening. The search and review process started in June 2020 and ended in August 2020. Articles were excluded if they were not specific to India, did not include any youth, were not discussing a specific programme or intervention that was conducted, did not include any promising practices or lessons learned for sexuality education programmes, or were not available in full-text versions despite contacting authors to request full text. Data from the final set of papers included in the review were extracted and recorded in an Excel spreadsheet. The programmes described in the final included papers were sorted and mapped according to the location, target population, type of programme, elements/components of the programme, and subjects covered within the programme. Promising practices were identified from the conclusions reported by the authors of the individual studies.

Results

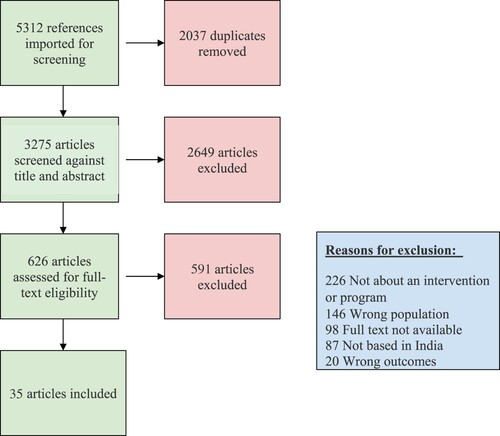

Our search strategy yielded a total of 5312 citations. That number was reduced to 3275 after excluding 2037 duplicate records. 626 of these moved onto full-text screening on the basis of their titles and abstracts. A final set of 35 articles met all inclusion criteria and were included in our scoping review. is our PRISMA chart of the selection process and includes the characteristics of the programmes of the selected papers. Key themes are presented below.

Table 2. Characteristics of individual sexual health education programmes for youth conducted in India

Programmes vary greatly across India

There is wide diversity in interventions and intervention-delivery mechanisms. Programmes were conducted either at the individual level, small-group level, or community/village wide. They were either implemented within the context of a school environment (majority of programmes – 24/35), or within a local community (10/35), or both (1/35). Overall, there is a great variety in the types of programmes that have been developed across the Indian context to provide sexual and reproductive health education to youth; no clear consensus was found across articles reviewed on which type of programme or programme components should be implemented within a specific setting.

Most programmes included a central didactic teaching component. There were differences across programmes in who taught the programme, with most programmes having health worker-led programming (19/35); 5 programmes were teacher-led, 5 were peer educator-led, 3 programmes were health worker and peer-led, 2 programmes were peer and teacher-led, and 1 programme was health-worker and teacher-led. Some programmes included a peer education component as the main method of information delivery (5/35), and a few included peer education as an additional supplement to their central delivery method through teachers or health professionals (5/35).

In our review, we charted the subjects covered by the included programmes. Certain topics were widely included in most programmes, such as: anatomy and physiology of male and female reproductive systems, changes during adolescence/puberty, sexual maturity, personal sexuality, navigating relationships, menstruation, pregnancy and family planning, STIs, and HIV/AIDS. Other topics were not as commonly included, such as: gender equity (9/35 programmes), gender-based violence (4/35), communication and personal skills development (7/35), and societal pressures faced by youth (3/35). In certain regions, local myths and misconceptions were addressed and debunked in the teaching, such as: popular myths surrounding STIs (gupt roga), nocturnal emissions (swapnadosh), the sex determination of the fetus, and culturally specific conditions like koro.Footnote* The number of programmes that included each individual topic is shown in .

Table 3. Topics covered by the included programmes

Diverse methods for delivering information increase programme success

Programmes that included time for group discussions found that attendees found the discussions beneficial, regardless of whether it was a structured focus group discussion or a more informal group discussion. Group discussions were reported to be a good opportunity to share personal experiences, ask questions, engage in conversation over similar experiences, and learn from others.Citation33,Citation47,Citation50,Citation52 Successful programmes also included visual aids, such as posters, diagrams, drawings and videos.Citation2,Citation60,Citation64,Citation66 Interactive and participatory exercises such as demonstrations, role-playing exercises, creating skits in groups, playing trivia games, and engaging in debates on relevant topics were also found by youth to be helpful in consolidating information they had learned.Citation44,Citation47,Citation59 Another important component that was found to be very appreciated by youth was the inclusion of some form of “question and answer” period; this could be through a formal discussion session or an anonymous submission box with answer provision sessions later on.Citation2,Citation43 Successful programmes also had the inclusion of take-home handouts or pamphlets to reinforce learning and potentially help extend the learning process to family members at home.Citation67,Citation74,Citation75,Citation77 Lastly, several programmes included the option of booking individual counselling sessions with trained counsellors or healthcare professionals for any personal concerns or topics they wanted to discuss in private.Citation44,Citation59,Citation67

Programmes that addressed a larger audience, such as a community as a whole, employed several elements to impart educational messaging. Some programmes included a large health “fair” or “mela,” youth health camps or festivals, rallies or parades to engage large groups of people.Citation46,Citation53,Citation66 Successful programmes, similar to the smaller programmes, included interactive and participatory exercises such as community plays, puppet shows, and street shows to engage youth and share information.Citation66,Citation70 Several programmes included visual aids such as posters, flyers, T-shirts, badges, and buttons to spread awareness throughout the community.Citation44,Citation49,Citation66,Citation74,Citation75 A few programmes included home-to-home visits to provide education and counselling on a more personal level, and others also set up youth health clinics in order to serve as a designated space for youth to access accurate information, connect with healthcare services, and discuss sexual health topics in a confidential setting.Citation53,Citation63,Citation78

Monitoring and evaluation is critical to programme success and sustainability

We also identified several recommendations from the reviewed articles regarding the development of all programmes, regardless of type. The importance of preliminary assessment of knowledge levels and needs of youth in the target community prior to the development of the programme was emphasised by all programmes. Including continuous quality monitoring and evaluation of programme delivery was very important to ensure that the programme curriculum was being delivered correctly.Citation66 Through the process of monitoring, programmes were able to determine whether a certain curriculum was making progress towards its specific goals and objectives. Furthermore, by checking-in with programme educators, programmes were able to address educator feedback, provide them with support and answer any questions or concerns they may have as these come up.Citation48,Citation56 In some programmes, refresher training sessions were conducted for educators at set intervals during the programme duration.Citation48,Citation53,Citation63,Citation66,Citation67 Other components of monitoring included assessment of inputs and required resources (i.e. programme funding, employees, duration of programme activities, needed equipment/supplies, and facilities) and programme outputs (i.e. student knowledge, skills developed, feedback received).Citation47,Citation48,Citation66,Citation70 Evaluation is the process of examining whether the programme’s objectives have been achieved. Evaluation processes, typically conducted at the conclusion of the programme delivery, provided valuable information on longer-term impacts of the programme and feedback for future iterations or expansion of programme delivery. Thorough assessment and evaluation of programme delivery provide information on who was actually reached by the curriculum and the measurable impact made, such as changes in knowledge, attitudes, and skills among participants, through methods such as document analysis, participant interviews, focus group discussions, and surveys.Citation33,Citation59,Citation67,Citation70

Resources and time allocated by educators make a difference

There is a great diversity in the educators that lead the programmes identified in our review, including community members, youth group leaders, peer educators, and formal school teachers. There are benefits and drawbacks for each type of instructor choice, and there is no established preferred option in the literature. Drawing on existing staff resources, such as school teachers, ensures sustainability and allows for rapid implementation and potential scale-up of activities. At the same time, if the educators delivering the programme have another primary responsibility, the effectiveness of the programme may be compromised. A major recommendation that emerged from the literature was making sexuality education a core subject within the regular school curriculum.Citation47,Citation52,Citation64,Citation66 This would help emphasise the importance of sexual health and reproductive health education for youth, ensure that adequate time and resources are allocated to its teaching, and could allow students to study the topics covered without worrying about sacrificing study time for their other classes.Citation66

Some programmes delivered their programme through health professionals and health counsellors. Since these educators were solely assigned to the programme delivery, their time to dedicate to the programme was protected and was greater than programmes that relied on school teachers, for example. The “SHAPE” programme was delivered by school health counsellorsCitation67 and the “SEHER” programme utilised lay counsellors for the delivery of their intervention activities.Citation70 Both programmes found that one of the greatest strengths of counsellor-led delivery was the focused time and coverage they were able to provide. However, the “SEHER” programme noted that there was an increased cost associated with the hiring and training of counsellors in their delivery model compared to a teacher-led programme.Citation70

Several successful programmes have also utilised peer-led education as their primary method of delivery. Peer educators may require considerable training before they have the knowledge and skills to implement an educational programme. Overall, the evidence on the utility of peer educators is mixed.Citation79 Youth may be more receptive and open to peer educators given the similarity in age and stage in life. Peer education can be helpful in terms of promoting peer-to-peer support and an open environment for the discussion of sensitive topics.Citation80 One systematic review of literature from the Indian context found overall mixed results for peer education and its effects on behaviour, but proposed that, while it has its limitations, it can be a valuable component of sexual health education efforts.Citation77 Peer education may be most beneficial when it is included as a part of a multicomponent, holistic intervention for youth.Citation78,Citation81

Community and youth involvement increase the acceptability of programmes

The importance of fostering and engaging local organisations and community resources was emphasised across the reviewed literature as a key component for ensuring success and longevity of the implemented programme and curriculum within the Indian context. Engaging community leaders, community stakeholders and local experts in the creation, development and implementation process were vital to the success and feasibility of all programmes.Citation79 Programmes that included local leaders such as principals, school teachers, village council leaders and local NGOs or organisations were able to develop and run programmes effectively and were well-received by the community with which they were working in partnership. Fostering a supportive and receptive environment is critical for the successful initiation and continuation of sexuality education programmes. By working with and mobilising the community, empowerment of participants, support for programme expansion, the involvement of a greater range of stakeholders, wider awareness through mass media and local channels, as well as advocacy for greater social issues can be established.Citation79

Several programmes established partnerships with local organisations and community leaders to provide feedback, assist in the programme development, and monitor implementation.Citation56,Citation59,Citation63,Citation64,Citation70 Certain programmes even established a formal advisory board composed of local stakeholders, local organisation leaders and community representatives to provide continuous feedback on a regular basis throughout programme implementation.Citation44,Citation48,Citation67,Citation74 Establishing community support can help to promote sustainability and increased engagement from community members.Citation48 Several programmes conducted needs assessments and consulted with local stakeholders such as parents and teachers during the development process.Citation43,Citation50,Citation58,Citation60,Citation67,Citation69 However, consultation with local youth is especially important, as youth perspectives can often be overlooked in decision-making processes.Citation9 Youth themselves can play an integral role in identifying and advocating for their own needs.Citation79 Among the 35 individual programmes, only 4 reported consulting with local youth in the development and initiation of their programmes. For example, in the “DISHA” programme, a confidential access point for individualised counselling and provision of contraceptive products was established based on input from youth.Citation53

Furthermore, partnerships with local NGOs and health centres were found to play a significant role in ensuring buy-in from diverse stakeholders in 13/35 of the reviewed programmes. They were also found to help programmes liaise with various school systems, communities, villages, agencies, and institutions. These organisations provided valuable assistance in the development of tools and systems for the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of educational programmes. Furthermore, partnering with local health services helped to strengthen community and youth access to sexual health information and clinical services.Citation49,Citation51,Citation53

Access to high-quality education enhances reproductive health outcomes

Limitations of school-based sexuality education provision include the underlying assumptions that (1) all or most youth we are trying to reach are in fact attending school and have been able to attend school uninterrupted since childhood, and (2) their education up to this point has been of satisfactory quality, and has provided them with the opportunity to develop the required literacy, numeracy, critical thinking and communication skills necessary to build a solid foundation in sexual health decision-making and navigating relationships. Several articles in the reviewed literature raised concerns about the applicability of school-based approaches to promoting sexual and reproductive health because of these limitations.Citation82 One working paper published by the Population Council found that the implementation of sexual health education programmes has little impact in Indian schools where teachers require more training and where students have not attained basic skills such as literacy and numeracy. The authors also found a strong overlap between youth most at-risk for poor health outcomes and youth who were most disadvantaged educationally. They postulated that for many of these students, improvement in their basic literacy and numeracy skills may itself be the most significant and promising intervention in terms of their reproductive health outcomes.Citation82

Access to schooling itself can play a great role in sexual health outcomes for youth and young adults. Prevention of early marriage, in particular, is important in ensuring continued access to schooling for youth, especially for women and girls in India. Keeping Indian youth enrolled in school is an effective way to prevent early marriage, as many studies completed in the Indian context and across the world have shown that youth enrolled in school are less likely to be married at an early age.Citation18 They are more likely to continue their post-secondary studies, apply for employment, and become financially independent. It is important to ensure access to high-quality education for all youth, and provide economic and social support for families to help prevent child marriage. One example of this was conducted through the Indian “DISHA” programme, where in addition to providing education on sexual health to youth, the programme introduced “livelihood groups” to address some of the socioeconomic barriers that youth face. The livelihoods component set up income-generating opportunities for youth along with training in employment-oriented skills. Some examples included training youth in skills such as pottery, tailoring, vegetable cultivation, rice production, candle-making and bangle decoration. The programme also linked youth to micro-saving and credit groups.Citation53

Reaching vulnerable youth requires out-of-school programming

For an intervention to have an impact on youth knowledge and behaviour, it must be able to reach them. A significant proportion of Indian youth, especially those who are most marginalised or vulnerable, are not being reached by interventions intended for them. These groups include: youth with disabilities, youth engaged in sex work, youth experiencing homelessness, youth with low literacy levels, migrant youth, and youth involved in the justice system. Most existing programmes focus on youth enrolled in schools and colleges rather than those outside the school system. Within our review 24/35 programmes were primarily school-based in their delivery. In India, there are higher rates of drop-out from school in girls than boys, and in those belonging to socioeconomically disadvantaged households over advantaged households. As a result, the most vulnerable youth are often not enrolled in school or involved in youth groups, so it can be difficult to reach them through these standard routes.Citation23,Citation78 For example, youth living in slum areas are less likely to be in school, are more likely to have significant stressors in their life, and they may live within a social system unique to slum communities (e.g. council of Elders, workers at Anganwadi rural childcare and community health centres). Therefore, it is important to reach them by developing and implementing interventions that involve and empower the existing community structure, local NGOs and available health services. For this reason, some programmes have tried unconventional delivery methods like providing education through barber-shops, wine shops, and radio shows.Citation45,Citation74,Citation83

Addressing gender inequality is essential to mitigating violence

While there is a growing body of work on programmes specifically focused on gender-related topics that are making targeted efforts to engage youth in understanding gender-based inequity, inclusion of this topic into comprehensive sexuality education is limited. Only one of the programmes included in the review incorporated gender equity and gender-based violence into their comprehensive sexual health curriculum. The programme consisted of peer-led group education activities, and participatory activities such as role-playing, debates, and critical thinking exercises. The programme was supported by monthly meetings where facilitators, field supervisors, as well as experts in the field of gender equity, met to discuss programme progress and implementation.Citation75 While many sexual health education programmes have acknowledged the importance of including discussion about gender inequity, gender-based norms, reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ rights and gender-based violence as part of their curriculum, resistance from individuals such as local school officials and parents, combined with the general taboo surrounding such topics, can make implementation difficult.Citation46,Citation84 Furthermore, the persistence of gender-based or sexuality-based inequity, especially if explicitly visible among staff at school or within the local environment, can undermine the utility of many sexual and reproductive health programmes.

One extensive review and analysis of a wide variety of evaluation studies of comprehensive sexuality education programmes from different global contexts and settings, including India, found that programmes that included gender and gender-based rights in their curriculum were more successful in improving sexual health outcomes for youth than “gender-blind” programmes. They also found that youth who adopt more egalitarian stances on gender and gender-based norms, are more likely to have a delayed sexual debut and use protection during sexual activity, and are less likely to be involved in intimate partner violence.Citation10 On a nation-wide scale, there is a need for greater inclusion, open discussion, and teaching of these topics in programmes for youth.

Supportive environments for comprehensive sexuality education are crucial for delivery

Interventions related to the upstream factors influencing youth health can be challenging to evaluate and develop. Barriers related to individual behaviour can be at the household, school, local community, regional or national level. Socioeconomic capital, access to required resources, healthcare service delivery, school and educational systems, social capital and social norms can all influence the sexual health of youth. It is important for youth to have a supportive environment that supports their educational and vocational attainment, in addition to socioeconomic security and social supports.Citation38 Along with sexuality education programmes aimed at increasing personal knowledge and related skills, interventions addressing these broader factors are concurrently required, in order to also increase employment, school retention, financial security, and social support for youth. Integrated programmes like these result in better outcomes and greater impact. For example, in the “Saloni” pilot programme, multiple upstream preventative health interventions for adolescents were introduced through the school system that addressed multiple areas of youth health including nutritional deficiencies, reproductive health, and physical hygiene. The “Saloni” programme included 10 in-school sessions and take-home activities for their participants. The study team reported approximately 65% of the girls in the intervention group had adopted 13 or more new positive preventative health behaviours in the areas of nutrition, hygiene and reproductive health, by the end of the programme compared to 4.5% in the control group and 5% at baseline.Citation54

Discussion

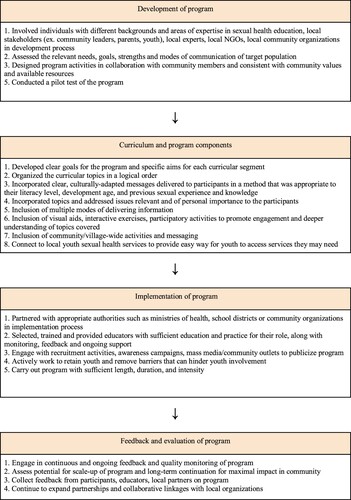

This review has demonstrated that there is a wide variety of interventions and programmes that have been developed and implemented to address the need for sexuality education for youth in India. There are many different types of programmes and there is no consensus within the literature with regard to which are the most successful with youth, although what is most feasible and useful is likely driven by the specific context and needs of the population being targeted. The main take-aways are summarised in . We found that successful programmes required a diverse team to support development, including experts in sexuality education, local community leaders, parents, youth, NGOs, and community organisations. Prior to programme debut, it was important to complete a needs assessment of the target population in order to create a personalised programme tailored to meet the needs of the community. With regards to curricular development, it was important to develop specific objectives for the programme, and to deliver programming using culturally appropriate messaging that was also tailored to the literary and developmental level of the participants. Having a variety of methods for delivering information was also highlighted, for example: the use of visual aids, interactive exercises, participatory activities, reflection exercises, group projects, and community/village-wide activities and events. Providing youth with follow-up by way of connection to local sexual health services and/or take-home resources was also found to be helpful for youth. Implementation of the programme should be delivered over a sufficient length, duration, and level of intensity via well-trained educators with ongoing monitoring and support for their performance. Overall, engagement in continuous ongoing feedback and quality monitoring of the programme is vital for the understanding of programme impact, assessing the potential for long-term continuation and/or expansion, and developing further partnerships and collaborative linkages with related organisations and stakeholders.

Few programmes identified in the scoping review explicitly addressed gender inequity and gender-based violence in their content. Gender – a societal construct - can permeate all aspects of youth health, especially sexual and reproductive health. In ancient Indian society, women were treated and valued as having equal status to men.Citation85 Patriarchy entered Indian society in the post-Vedic era, with Victorian gender norms and puritanical principles notably imposed by the colonial rule of Britain, including the penal code. Youth of all genders are impacted by limited access to sexual health information, and by societal norms that dissuade open dialogue on sexual violence, consent, and respect in intimate relationships; however, the impact is arguably more pronounced for women, who face enhanced gender-based oppression through the patriarchal norms of post-Vedic Indian society and are correspondingly more likely to face sexual violence.

When comparing the promising practices identified in our review with the globally-defined best practices for CSE established by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), we found many similarities between the two, and no contradictions. Our review corroborated several practices also recommended by UNESCO. Specifically, the UNESCO guidelines also emphasise the importance of sufficient preparation and groundwork within the target community before implementation, with the development of links to existing community resources and partners in order to support future sustainability of the programme. This is especially important in the Indian context, due to unique sociocultural settings of various communities across the country. The vast diversity in sociocultural norms, language, religious, financial, and economic conditions necessitates that new programmes are developed specifically for the individual setting for which they are planned. Specific areas of focus unique to India for new sexuality education programmes include the topics of gender-based equity, gender-based violence, as well as local culture-bound syndromes such as koro. Both the UNESCO guidelines and our review support the importance of consulting stakeholder groups, establishing a local steering committee supported by community organisations, conducting an assessment of local youth needs, determining focused and measurable programme goals and outcomes, and developing a framework for curricular activity based on the population reference values and existing educational resources. As stated in the UNESCO guidelines, and also confirmed by the studies in our review, after the development of the programme, it is key to pilot test before launching the programme, and then continue to monitor and evaluate the programme on an ongoing basis to assess outcomes and scale-up as possible. Both UNESCO and our review also found that the programme itself should be specific to the needs of the community, with use of participatory teaching methods, targeting risk and protective factors that may be present while also providing youth with practical skills and scientifically accurate information about sexual and reproductive health.Citation3 As previously discussed, providing youth with practical skills is especially important in the Indian context, where providing youth with practical skills that they can leverage to improve their socioeconomic status is key in breaking the cycle of lower educational attainment, decreased social and employment opportunities, and negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

Areas of paucity and goals for the future

We aim for the results of this paper to help guide educators and public health organisations in the creation, implementation, and evaluation of CSE programmes for youth within the context of India but also any other similar settings. Our work also provides an example of a framework for evaluating sexuality education programmes and provides a comprehensive overview of factors that are important to consider in the development and assessment of these initiatives. This review offers educators, programme planners, and policy makers an in-depth look into the current state of sexuality education programmes in India, and various strengths, weaknesses, and key lessons learned by these various groups in their endeavours to deliver sexuality education for youth. Sexuality education must be shaped by awareness of what works for youth and be adaptable according to the changing needs of young people. For example, we identified the specific need for greater incorporation of education surrounding gender-based stereotyping and prevention both on the individual and community level for the prevention of gender-based violence within the Indian context.

We identified several gaps and areas for future work and research in the literature. There is a need to generate more robust and standardised data on the outcomes of sexuality education programmes. Much of the global literature on interventions to promote sexual and reproductive health among youth has noted a need for more rigorous and theory-based research to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in improving youth knowledge and changing health behaviours and outcomes.Citation78,Citation86–88

One of the limitations of our review is the restricted ability to accurately compare programmes across different settings and target population groups. Even within the context of India alone, there is a huge diversity across programmes in the types of activities, components, curricula, outcomes measured and methods of implementation. Due to this variety in the outcomes and reported measurement methods, it is understandably difficult to draw accurate conclusions about the field and cross-compare between different programmes. There is currently no consensus on whether teacher-taught, peer-taught, counsellor/health worker-taught programmes are all effective or if one of these methods is better in a given context, largely because of lack of meaningful evaluation approaches that are standardised while also context-specific. Similarly, there is no consensus currently on which programme length, duration of sessions, or number of sessions is most effective in a given context, although it has been shown that any type of intervention when delivered piecemeal or with inadequate dosage is not as successful.Citation2,Citation53,Citation78

Further research on the costs and benefits, using validated and context-specific measures of effectiveness, will be important for decisions on how to allocate resources for programmes for health promotion. Longer-term tracking of health and social outcomes for the participants of a programme is also important, as many of the potential benefits may not be measurable in the short term.Citation2 Standardised and validated outcome measures should be utilised to allow for effective comparability between programmes. Research should be conducted across a wide variety of sociocultural contexts to identify feasible and effectual programmes that work among youth to reduce negative sexual health outcomes, especially in resource-limited settings.Citation86 Evidence-based and successful programmes should be scaled up, delivered with adequate intensity and sustained long-term.Citation2,Citation78,Citation89

Conclusion

Personal knowledge and skills development related to sexuality is an important determinant of health during adolescence and young adulthood. As part of a broader sexual health promotion strategy addressing both downstream and upstream determinants of healthy sexuality, the delivery of CSE for young people has a significant impact on promoting overall wellbeing. It serves as a crucial prevention tool for adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes, including unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections, HIV/AIDS, and sexual violence. Moreover, CSE is an integral prerequisite to full-body autonomy and thus intimately tied to human rights.

In this scoping review, we endeavoured to identify components and characteristics of successful sexuality education programmes, to inform promising practices for the development of programmes for youth in India. CSE programmes, in combination with access to sexual health services, are vital for providing youth with comprehensive knowledge on the topic as well as providing youth with the skills to navigate sexual and reproductive health-related decisions. The Indian context is very diverse, and not all identified promising practices may be applicable for all locales and populations. It is important for existing programmes and those looking to develop new programmes to tailor their content to serve the needs of the specific youth population being targeted; to work in partnership with local experts and organisations; to address potential barriers to participation and work to mitigate those barriers for marginalised youth; to be youth-friendly, flexible and convenient; and be developmentally and culturally appropriate for the Indian youth context.Citation51

A myriad of micro- and macro-level factors can lead to negative sexual health outcomes among youth and young adults, from family and community pressures, social norms and expectations, to educational attainment and financial constraints. Continued efforts are required by different sectors and stakeholders to address the interrelated and broad structural factors, including political, financial, social, and cultural, that affect youth sexual health and wellbeing.

Appendix 1: Full Search Strategy

Download MS Word (31.2 KB)Acknowledgements

Sandra Halliday from Bracken Health Sciences Library at Queen’s University provided guidance in developing and implementing the search strategy. Natalie DiMaio assisted in the citation screen as the second reviewer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://do.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2244268.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* Koro is a psychiatric culture-bound syndrome characterised by intense fear that the sexual organs (i.e. penis, breasts) will retract into the body. It has been found to be most prevalent in populations within South Asia and South East Asia.

References

- Shahbaz S. Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in Asia: a regional brief. Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW); 2018.

- Kirby D, Laris BA, Rolleri L. Impact of sex and HIV education programs on sexual behaviors of youth in developing and developed countries. Family Health International, YouthNet Program Durham, NC; 2005.

- UNESCO. Emerging evidence, lessons and practice in comprehensive sexuality education: a global review. UNESCO Paris; 2015.

- Fonner VA, Armstrong KS, Kennedy CE, et al. School based sex education and HIV prevention in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e89692. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089692

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [Internet]. OHCHR. [cited 2022 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights.

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women New York. [Internet]. OHCHR; 18 December 1979. [cited 2022 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women.

- Convention on the Rights of the Child [Internet]. OHCHR. [cited 2022 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

- Comprehensive sexuality education [Internet]. United Nations Population Fund. [cited 2022 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/comprehensive-sexuality-education.

- Roy A, Roy R. Bengali youth speak out for change: knowledge and empowerment of youth in West Bengal, India. In: S Bastien, HB Holmarsdottir, editors. Youth’at the margins’. Rotterdam: Brill Sense; 2015. p. 123–151.

- United Nations Population Fund. The evaluation of comprehensive sexuality education programmes [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2021 Apr 12]. Available from: /publications/evaluation-comprehensive-sexuality-education-programmes.

- Roy A, Roy R. “There is a lot of embarrassment”: reflections of students and educators on sex education in West Bengal, India. Clin Investig Med. 2015;38(6):E335–E336.

- Paranjape RS, Challacombe SJ. HIV/AIDS in India: an overview of the Indian epidemic. Oral Dis. 2016;22:10–14. doi:10.1111/odi.12457

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Saggurti N, et al. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among married Indian women. Jama. 2008;300(6):703–710. doi:10.1001/jama.300.6.703

- Ekstrand ML, Bharat S, Srinivasan K. HIV stigma is a barrier to achieving 90-90-90 in India. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(10):e543–e545. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30246-7

- World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization; 2013.

- Raj A, McDougal L. Sexual violence and rape in India. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):865. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60435-9

- Saravanan S. Violence against women in India. New Delhi: Institute of Social Studies Trust; 2000.

- Chandra-Mouli V, Camacho AV, Michaud PA. WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):517–522. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.002

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009;374(9693):881–892. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive health outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. World Health Organization; 2011.

- United Nations. Population and development: programme of action adopted at the international conference on population and development, Cairo, 5–13 September 1994. Vol. 1. New York: United Nations, Department for Economic and Social Information and … ; 1995.

- Barua A, Chandra-Mouli V. The Tarunya Project’s efforts to improve the quality of adolescent reproductive and sexual health services in Jharkhand state, India: a post-hoc evaluation. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;29(6). doi:10.1515/ijamh-2016-0024

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Santhya KG. Sexual and reproductive health of young people in India: a review of policies, laws and programmes; 2011.

- Chakravarti P. The sex education debates: teaching ‘Life Style’ in West Bengal, India. Sex Educ. 2011;11(4):389–400. doi:10.1080/14681811.2011.595230

- Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports (MOYAS). Annual Report 2010–2011. New Delhi: MOYAS, Government of India; 2011.

- Kansara K, Saxena D, Puwar T, et al. Convergence and outreach for successful implementation of Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram. Indian J Community Med. 2018;43(Suppl 1):S18.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Annual Report 2018-2019: National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) [Internet]; 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/24%20Chapter%20496AN2018-19.pdf.

- Ram U, Mohanty SK, Singh A, et al. Youth in India: situation and needs 2006–2007. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Population Council; 2010.

- Sivagurunathan C, Umadevi R, Rama R, et al. Adolescent health: present status and its related programmes in India. Are we in the right direction? JCDR. 2015;9(3):LE01.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian best practices Portal [Internet]; 2015 [cited 2021 Nov 26]. Available from: https://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/interventions/search-interventions/.

- Beyers C. Sexuality education in South Africa: A sociocultural perspective. Acta Acad. 2011;43(3):192–209.

- Braeken D, Cardinal M. Comprehensive sexuality education as a means of promoting sexual health. Int J Sex Health. 2008;20(1–2):50–62. doi:10.1080/19317610802157051

- Dei Jnr LA. The efficacy of HIV and sex education interventions among youths in developing countries: a review. Scient Acad Publ. 2016;6(1):1–17.

- Huaynoca S, Chandra-Mouli V, Yaqub Jr N, et al. Scaling up comprehensive sexuality education in Nigeria: from national policy to nationwide application. Sex Educ. 2014;14(2):191–209. doi:10.1080/14681811.2013.856292

- Parker R, Wellings K, Lazarus JV. Sexuality education in Europe: an overview of current policies. Sex Educ. 2009;9(3):227–242. doi:10.1080/14681810903059060

- Yankah E. International framework for sexuality education. Evidence-based approaches to sexuality education: a global perspective. New York: Routledge; 2016, p. 17–32.

- Vanwesenbeeck I, Westeneng J, de Boer T, et al. Lessons learned from a decade implementing comprehensive sexuality education in resource poor settings: the world starts with me. Sex Educ. 2016;16(5):471–486. doi:10.1080/14681811.2015.1111203

- Hardee K, Gay J, Croce-Galis M, et al. What HIV programs work for adolescent girls? JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S176–S185. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000182

- World Health Organization. Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for actions: global report. World Health Organization. 2002.

- Chrisler JC, Johnston-Robledo I. The (un)healthy body. Woman’s embodied self: feminist perspectives on identity and image. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2018, p. 123–140.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005 Feb 1;8(1):19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available from: www.covidence.org.

- Arora A, Mittal A, Pathania D, et al. Impact of health education on knowledge and practices about menstruation among adolescent school girls of rural part of district Ambala, Haryana. Indian J Community Health. 2013;25(4):492–497.

- Balaji M, Andrews T, Andrew G, et al. The acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of a population-based intervention to promote youth health: an exploratory study in Goa, India. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(5):453–460. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.029

- Bhasin U, Singhal A. Participatory approaches to message design: ‘Jeevan Saumbh’, a pioneering radio serial in India for adolescents. Media Asia. 1998;25(1):12–18. doi:10.1080/01296612.1998.11726544

- Capoor I, Mehta S. Talking about love and sex in adolescent health fairs in India. Reprod Health Matters. 1995;3(5):22–27. doi:10.1016/0968-8080(95)90078-0

- Chandra-Mouli V, Plesons M, Barua A, et al. What did it take to scale up and sustain Udaan, a school-based adolescent education program in Jharkhand, India? Am J Sex Educ. 2018;13(2):147–169. doi:10.1080/15546128.2018.1438949

- Chhabra R, Springer C, Leu CS, et al. Adaptation of an alcohol and HIV school-based prevention program for teens. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):177–184. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9739-3

- Daniel EE, Hainsworth G, Kitzandtides I, et al. PRACHAR: advancing young people’s sexual and reproductive health and rights in India. Watertown (MA): Pathfinder; 2013.

- Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. The effect of community-based health education intervention on management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health Popul. 2007;9(3):48–54. doi:10.12927/whp.2007.19303

- Ghule M, Donta B. Sexual behaviour of rural college youth in Maharashtra, India: an intervention study. J Reprod Contracept. 2008;19(3):167–189. doi:10.1016/S1001-7844(08)60020-6

- Jadon G. Impact of reproductive health education on the knowledge of mid adolescents boys of urban population of Haryana. IP Int J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2018;4(1):20–32.

- Kanesathasan A, Cardinal LJ, Pearson E, et al. Catalyzing change: improving youth sexual and reproductive health through DISHA, an integrated program in India. Washington (DC): International Center for Research on Women; 2008.

- Kapadia-Kundu N, Storey D, Safi B, et al. Seeds of prevention: the impact on health behaviors of young adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh, India, a cluster randomized control trial. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:169–179. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.002

- Kokiwar PR, Nikitha P. Efficacy of focused group discussion on knowledge and practices related to menstruation among adolescent girls of rural areas of RHTC of a Medical College: an interventional study. Indian J Community Med. 2020;45(1):32–35. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_134_19.

- Leventhal KS, DeMaria LM, Gillham JE, et al. A psychosocial resilience curriculum provides the “missing piece” to boost adolescent physical health: a randomized controlled trial of girls first in India. Soc Sci Med. 2016;161:37–46. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.004

- Malleshappa K, Krishna S. Knowledge and attitude about reproductive health among rural adolescent girls in Kuppam mandal: an intervention study. Biomed Res. 2011;22(3):305–310.

- Manjula R, Kashinakunti SV, Geethalakshmi RG, et al. An educational intervention study on adolescent reproductive health among pre-university girls in Davangere district, South India. Ann Tropical Med Public Health. 2012;5(3):185. doi:10.4103/1755-6783.98612

- Mehra D, Sarkar A, Sreenath P, et al. Effectiveness of a community based intervention to delay early marriage, early pregnancy and improve school retention among adolescents in India. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5586-3

- Minimol G. Preparing girls for menarche. Nurs J India. 2003;94(3):54.

- Nair MK, Paul MK, Leena ML, et al. Effectiveness of a reproductive sexual health education package among school going adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79(Suppl 1):S64–S68. doi:10.1007/s12098-011-0433-x.

- Nayak M. Effectiveness of video assisted teaching module on knowledge of adolescent girls regarding polycystic ovarian syndrome in Gayatri Women’s +2 Science College, Berhampur Ganjam, Odisha. i-Manager's J Nurs. 2017;7(2):27–31.

- Patel P, Puwar T, Shah N, et al. Improving adolescent health: learnings from an interventional study in Gujarat, India. Indian J Commun Med Official Publ Indian Assoc Prevent Social Med. 2018;43(Suppl 1):S12.

- Phulambrikar RM, Kharde AL, Mahavarakar VN, et al. Effectiveness of interventional reproductive and sexual health education among school going adolescent girls in rural area. Indian J Community Med. 2019;44(4):378–382. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_155_19

- Premila E, Ganesh K, Chaitanya BL. Impact of planned health education programme on knowledge and practice regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls studying in selected high school in Puducherry. Asia Pacific J Res. 2015;1(25):154–162.

- Rajaraman D, Shinde S, Patel V. School health promotion programmes in India: a casebook. New Delhi: Byword Publications; 2015.

- Rajaraman D, Travasso S, Chatterjee A, et al. The acceptability, feasibility and impact of a lay health counsellor delivered health promoting schools programme in India: a case study evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-127

- Rao RS, Lena A, Nair NS, et al. Effectiveness of reproductive health education among rural adolescent girls: a school based intervention study in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka. Indian J Med Sci. 2008 Nov;62(11):439–443. doi:10.4103/0019-5359.48455

- Sharma S, Nagar S, Chopra G. Health awareness of rural adolescent girls: an intervention study. J Soc Sci. 2009;21(2):99–104. doi:10.1080/09718923.2009.11892758

- Shinde S, Pereira B, Khandeparkar P, et al. The development and pilot testing of a multicomponent health promotion intervention (SEHER) for secondary schools in Bihar, India. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1385284. doi:10.1080/16549716.2017.1385284

- Singh S. Study of the effect of information, motivation and behavioural skills (IMB) intervention in changing AIDS risk behaviour in female university students. AIDS Care. 2003;15(1):71–76. doi:10.1080/095401202100039770.

- Thakor HG, Kumar P. Impact assessment of school-based sex education program amongst adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2000;67(8):551–558. doi:10.1007/BF02758475.

- Tilak VW, Bhalwar R. Effectiveness of a health educational package for AIDS prevention among adolescent school children. Med J Armed Forces India. 1998;54(4):305–308. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(17)30590-7.

- Van Rompay KK, Madhivanan P, Rafiq M, et al. Empowering the people: development of an HIV peer education model for low literacy rural communities in India. Hum Resour Health. 2008;6(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-6-6

- Verma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra VS, et al. Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India; 2008.

- Visaria L, Mishra RN. Health training programme for adolescent girls: some lessons from India’s NGO initiative. J Health Manag. 2017;19(1):97–108. doi:10.1177/0972063416682586

- Siddiqui M, Kataria I, Watson K, et al. A systematic review of the evidence on peer education programmes for promoting the sexual and reproductive health of young people in India. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(1):1741494. doi:10.1080/26410397.2020.1741494

- Chandra-Mouli V, Lane C, Wong S. What does not work in adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a review of evidence on interventions commonly accepted as best practices. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(3):333–340. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00126

- Senderowitz J. A review of program approaches to adolescent reproductive health. Arlington (VA): US Agency for International Development Bureau for Global Programs/Population Technical Assistance Project; 2000.

- Swartz S, Deutsch C, Makoae M, et al. Measuring change in vulnerable adolescents: findings from a peer education evaluation in South Africa. SAHARA-J: J Social Aspects of HIV/Aids. 2012;9(4):242–254. doi:10.1080/17290376.2012.745696

- Michielsen K, Beauclair R, Delva W, et al. Effectiveness of a peer-led HIV prevention intervention in secondary schools in Rwanda: results from a non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-729

- Lloyd C. The role of schools in promoting sexual and reproductive health among adolescents in developing countries poverty. Gender and Youth Working Paper; 2007.

- Sivaram S, Johnson S, Bentley ME, et al. Exploring “wine shops” as a venue for HIV prevention interventions in urban India. J Urban Health. 2007;84(4):563–576. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9196-0

- Jejeebhoy S, Sebastian M. Actions that protect: promoting sexual and reproductive health and choice among young people in India. Reproductive Health [Internet]; 2003. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/528.

- Ray S. Understanding patriarchy. Human Rights Gender Environ. 2006;1(1):1–21.

- Kasedde S, Kapogiannis BG, McClure C, et al. Executive summary: opportunities for action and impact to address HIV and AIDS in adolescents. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S139–S143. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000206

- Denno DM, Hoopes AJ, Chandra-Mouli V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J Adolescent Health. 2015;56(1):S22–S41. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.012

- Schunter BT, Cheng WS, Kendall M, et al. Lessons learned from a review of interventions for adolescent and young key populations in Asia pacific and opportunities for programming. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S186–S192. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000185

- Salam RA, Faqqah A, Sajjad N, et al. Improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a systematic review of potential interventions. J Adolescent Health. 2016;59(4):S11–S28. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.022