Abstract

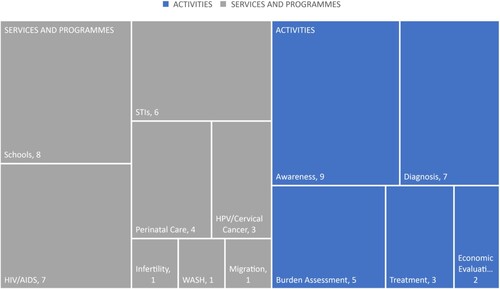

Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) affects approximately 56 million women and girls across sub-Saharan Africa and is associated with up to a threefold increased prevalence of HIV. Integrating FGS with HIV programmes as part of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services may be one of the most significant missed opportunities for preventing HIV incidence among girls and women. A search of studies published until October 2021 via Scopus and ProQuest was conducted using PRISMA guidelines to assess how FGS can be integrated into HIV/SRH and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) programmes and services. Data extraction included studies that integrated interventions and described the opportunities and challenges. A total of 334 studies were identified, with 22 eligible for analysis and summarised conducting a descriptive numerical analysis and qualitative review. We adapted a framework for integrated implementation of FGS, HIV, and HPV/cervical cancer to thematically organise the results, classifying them into five themes: awareness and community engagement, diagnosis, treatment, burden assessment, and economic evaluation. Most activities pertained to awareness and community engagement (n = 9), diagnosis (n = 9) and were primarily connected to HIV/AIDS (n = 8) and school-based services and programming (n = 8). The studies mainly described the opportunities and challenges for integration, rather than presenting results from implemented integration interventions, highlighting an evidence gap on FGS integration into HIV/SRH and NTD programmes. Investments are needed to realise the potential of FGS integration to address the burden of this neglected disease and improve HIV and SRH outcomes for millions of women and girls at risk.

Résumé

La schistosomiase génitale féminine touche près de 56 millions de femmes et de filles en Afrique subsaharienne et est associée à une prévalence du VIH jusqu’à trois fois supérieure. L’intégration de la schistosomiase génitale féminine dans les programmes de prise en charge du VIH dans le cadre de services complets de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR) est peut-être l’une des principales occasions manquées pour prévenir l’incidence du VIH chez les filles et les femmes. Une recherche d’études publiées jusqu’en octobre 2021 via Scopus et ProQuest a été réalisée à l’aide des directives PRISMA pour évaluer comment la schistosomiase génitale féminine peut être intégrée dans les programmes et services liés au VIH/à la SSR et aux maladies tropicales négligées (MTN). L’extraction des données comprenait des études qui intégraient des interventions et décrivaient les opportunités et les difficultés. Au total, 334 études ont été identifiées, dont 22 éligibles pour l’analyse qui ont été résumées en effectuant une analyse numérique descriptive et un examen qualitatif. Nous avons adapté un cadre de mise en œuvre intégrée concernant la schistosomiase génitale féminine, le VIH et le VPH/cancer du col de l’utérus pour organiser les résultats en les classant selon cinq thèmes: sensibilisation et participation communautaire, diagnostic, traitement, évaluation de la charge et évaluation économique. La plupart des activités concernaient la sensibilisation et la participation communautaire (n = 9), le diagnostic (n = 9) et étaient principalement en lien avec le VIH/sida (n = 8) et les services et programmes en milieu scolaire (n = 8). Les études décrivaient principalement les possibilités et les difficultés de l’intégration, plutôt que de présenter les résultats des interventions d’intégration mises en œuvre, soulignant un manque de données sur l’intégration de la schistosomiase génitale féminine dans les programmes relatifs au VIH/SSR et aux MTN. Des investissements sont nécessaires pour réaliser le potentiel de l’intégration de la schistosomiase génitale féminine en vue de réduire la charge de cette maladie négligée et d’améliorer les résultats en matière de VIH et de SSR pour des millions de femmes et de filles à risque.

Resumen

La esquistosomiasis genital femenina (EGF) afecta aproximadamente a 56 millones de mujeres y niñas en África subsahariana y está asociada con un aumento de hasta el triple de la prevalencia del VIH. Integrar la EGF en los programas de VIH como parte de los servicios integrales de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) posiblemente sea una de las oportunidades perdidas más importantes para prevenir la incidencia del VIH entre niñas y mujeres. Se realizó una búsqueda de estudios publicados hasta octubre de 2021 vía Scopus y ProQuest utilizando las directrices de PRISMA para evaluar cómo integrar la EGF en los programas y servicios de VIH/SSR y de enfermedades tropicales desatendidas (ETD). La extracción de datos abarcó estudios que integraron intervenciones y describieron las oportunidades y los retos. Se identificó un total de 334 estudios, de los cuales 22 eran elegibles para análisis y fueron resumidos al realizarse el análisis numérico descriptivo y la revisión cualitativa. Adaptamos un marco para la ejecución de programas integrados de EGF, VIH y VPH/cáncer cervical para organizar temáticamente los resultados, clasificándolos en cinco temas: conocimiento y participación de la comunidad, diagnóstico, tratamiento, evaluación de la carga y evaluación económica. La mayoría de las actividades atañían al conocimiento y la participación de la comunidad (n = 9), diagnóstico (n = 9) y estaban asociadas principalmente con servicios y programas de VIH/SIDA (n = 8) y escolares (n = 8). Los estudios describieron principalmente las oportunidades y los retos de integración, y no presentaron resultados de intervenciones de integración ejecutadas, lo cual pone de relieve la brecha de evidencia de integración de EGF en programas de VIH/SSR y ETD. Se necesitan inversiones para realizar el potencial de la integración de EGF para abordar la carga de esta enfermedad desatendida y mejorar los resultados de VIH y SSR para millones de mujeres y niñas en riesgo.

Introduction

Schistosomiasis is an acute and chronic disease caused by parasitic worms or schistosomes. It is a disease linked to extreme poverty and lack of access to safe water. People become infected when they come into contact with contaminated freshwater in which snails that carry schistosomes are living. There are two primary forms of schistosomiasis: intestinal and urogenital. The urogenital form of schistosomiasis is typically the result of infection with Schistosoma haematobium which is endemic throughout sub-Saharan Africa.Citation1,Citation2 If left untreated, the urogenital form can lead to female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) in women and girls, frequently resulting in severe reproductive health complications.Citation3,Citation4 FGS disproportionately affects women in poor, rural communities in sub-Saharan Africa where the prevalence of schistosomiasis is highest.Citation5,Citation6 However, some FGS cases are also reported in women living in African urban centres or migrants and travellers in high-income countries.Citation7

In endemic countries, schistosomiasis typically falls under Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) programmes and the primary form of prevention and treatment is mass drug administration (MDA) with the anti-parasitic drug, praziquantel, to all school-age children in communities at risk.Citation8,Citation9 While effective, this strategy often does not adequately address FGS. For example, girls are more likely to be absent from school and, therefore, miss the MDA. In addition, the strategy does not capture adult women who remain at risk for the disease.Citation9,Citation10

Diagnosing and managing FGS in the setting in which it occurs is a challenge.Citation7 Symptoms are typically non-specific (vaginal discharge, pain, bleeding, and infertility), leading to misdiagnosis as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or cervical cancer. Diagnosis is clinically based, with distinct lesions most commonly found on the cervix (but also elsewhere, such as the vaginal wall) during a pelvic examination. If left untreated, FGS can lead to subfertility or infertility and ectopic pregnancy.Citation7 Several studies have shown that the disease increases the risk for HIV acquisition.Citation11–14 In addition, recent studies also suggest FGS may be a co-factor for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and cervical cancerCitation15 although further studies are necessary to establish causation.

FGS is treatable and preventable. The World Health Organization (WHO) advises treatment with a single dose of praziquantel 40 mg/kg. The medicine kills the flukes and prevents the development of new lesions.Citation16–19 Also, the disease is preventable as the cycle of transmission may be interrupted when people have access to safe water, adequate sanitation, good hygiene, and preventive chemotherapy.Citation7 However, FGS continues to fall through the cracks of NTD and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) programmes, services, and policies because it is not recognised as an SRH condition, it is rarely recognised by health professionals, and largely unknown by communities living in schistosomiasis-endemic areas.

Integrating FGS prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment into SRH programmes and services, including HIV and cervical cancer services, has immense potential to strengthen the health system to reach the most marginalised women and girls with holistic women-centred health care.Citation20 Understanding how to integrate services is essential for us to rethink ways to address FGS and outline efficient strategies. Including FGS in WHO normative guidance for women’s health, and specifically SRH, can support national governments to integrate FGS interventions into their health planning, financing, and policy development. This can also support donors and multilateral agencies to include FGS as a component of comprehensive SRHR policies and to specifically acknowledge FGS in funding mechanisms for women’s health.

Several studies have highlighted the importance of integrating disease or sector-specific interventions into broader health services to improve health coverage and efficiency, for instance integrating HIV, WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene), and cervical cancer services.Citation21,Citation22 Yet, FGS-related reviews have focused on examining the association between FGS and HIV, diagnostic tools, and health education interventions.Citation14,Citation23,Citation24 We identified no reviews that looked at evidence associated with integration of FGS interventions into family planning, HIV and SRH programming, or other health services.

This scoping review undertook a systematic search of available literature to assess the opportunities and challenges associated with integrating FGS into HIV/SRH and NTD programmes and services. We adopted the integration model from Engels et al.Citation20 to assess and map results from selected studies. From our analysis, we then synthesised the existing opportunities and challenges for FGS integration. Based on the findings from this evidence, recommendations were generated to inform new integration initiatives and strategies for FGS integration within health programming, policy, advocacy, and research.

Methods

Study design

The authors conducted a scoping literature review using a systematic approach. This review followed Grant & Booth'sCitation25 recommendations for scoping reviews and the guidelines from The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).Citation26 These principles allowed the research team to perform a preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of the available research literature. Moreover, this methodology helped identify key concepts, interventions in place, and knowledge gaps. This strategy is particularly appropriate since the topic, FGS integration, has not yet been reviewed in the literature.Citation27

This review focused on FGS, “a urogenital presentation of schistosomiasis that refers to the presence of S. haematobium eggs, DNA, or characteristic clinical changes specifically in the genital tract” as defined by Sturt and colleagues (p. 3).Citation28 We opted to conceptualise integrated care for our search from a health systems approach as we understand that integration must embrace and address the multiple health needs of individuals and their communities. Therefore, we framed integrated care as health services that promote or provide a continuum of health care to all people. This includes coordinated action across the different levels of care aiming to deliver health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, management, and rehabilitation. This helped ensure that our search was not limited to integration interventions siloed within specific groups of diseases or constrained to health care delivery only.Citation29

Search strategy and selection criteria

A literature search for relevant studies was carried out in October 2021. The team searched peer-reviewed articles in two academic databases: Scopus and ProQuest. This database selection covers a wide range of sources and methodologies, providing different perspectives on the topic.

To assess how FGS can be integrated into HIV/SRH and NTD programmes and services, suitable terminology of search terms was based on a preliminary search and snowballing exercises. These search terms were categorised into four different search groups: schistosomiasis, SRH, neglected tropical diseases, and integrated. The digital bibliography – Mendeley version 1.19.4 – was used to collect and manage the results, and to remove duplicates from the search. All studies were screened according to the eligibility criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (see ) were derived from discussion and consensus among the authors. Studies were considered eligible for review if they adhered to the definitions of FGS and integrated care as previously described and if they had undergone peer review. Only empirical studies published up until October 2021 were selected. Articles in English, Spanish, and Portuguese were considered.

Table 1. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data extraction

The results from the search were compiled in a digital bibliography and divided equally among the authors. Three reviewers (FW, IUW, and MC) independently screened titles and abstracts, verifying the eligibility criteria. Titles for which an abstract was not available and records whose relevance was unclear were excluded. The authors discussed at each screening stage to mitigate discrepancies in decisions. AP resolved any disagreement on study inclusion between the screeners. FW, IUW, and MC independently extracted data to a descriptive-analytical Excel sheet and included studies after full-text assessments. The extraction sheet provided an overview of the included literature.

Analysis

The analysis of this review took a two-phase approach. First, we conducted a descriptive numerical analysis of the amount and distribution of the publications. Second, a qualitative review was undertaken to unpack and thematically organise the results.

We chose to use the adapted conceptual framework for integrated implementation of FGS, HIV, and HPV/cervical cancer.Citation20 During our review, Williams et al.Citation10 published a paper addressing FGS and FGS integration using a human rights lens to highlight that addressing FGS must go beyond clinical practice and is an issue that impedes achieving universal access to SRHR and Universal Health Coverage for all (Sustainable Development Goals 3 and 5). However, the authors concluded that the Engels et al.Citation20 framework was more appropriate here as it explicitly links FGS with HPV/cervical cancer and HIV services and indicates existing opportunities within the health system to reach girls and women. The model presents a way to expand access to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment through routine and existing services and programming. We adapted, from the original framework, the term “operational research goals” to activities. We added to the model the term “migration” as a sub-theme for services and programmes as it suits better the goals and scope of this review. We did not include the model from Williams et al.Citation10 in our review because it fell outside of the inclusion parameters; but we acknowledge its significance for reframing FGS as a gender equality, women’s rights, and health rights issue.

The thematic analysis consisted of a deductive search guided by the conceptual framework from Engels et al.Citation20 We classified the studies by type (i) activities – comprised of five sub-themes – and (ii) services and programmes – comprised of nine sub-themes. Neither category – theme or sub-theme – was exclusive.

Results

The findings of the study are reported in three sections. In the first section, we present the selection of the publications. In the second section, we describe the characteristics of the studies examined. In the third section, we explore the themes connected with elements for FGS integration.

Selection of the publications

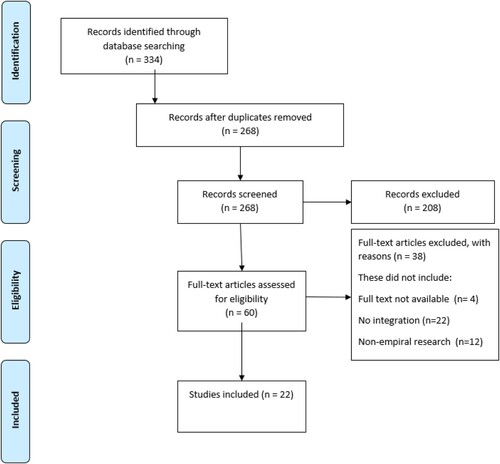

The PRISMA are presented in .Citation26 Of the 334 identified studies, 268 remained once duplicates (n = 66) were removed. Following initial screening, 208 articles were excluded based on the eligibility criteria. The authors assessed the remaining 60 articles in full text. After the full-text appraisal, 38 articles were rejected. Studies were excluded if they did not focus on FGS elements of integration (n = 9) or were non-empirical research (n = 12). Additionally, the authors excluded articles to which they did not have access (n = 4). This left 22 remaining articles for inclusion in the review (see ).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram for selection of publicationsCitation26

Characteristics of the included publications

Of the 22 articles included in the full-text review, the vast majority (n = 16, 72.27%) were published after 2015. Most of the study sites were in anglophone sub-Saharan Africa (n = 22, 84.61%), with Tanzania (n = 5, 19.23%) and South Africa (n = 5, 19.23%) being the preeminent sites for FGS research. The majority of citations, 68.18% (n = 15), were published in journals focused on NTDs, 13.6% (n = 3) in SRH journals, and 18.18% (n = 4) in broader public health-focused journals. Further, almost all (n = 19, 86.36%) studies utilised an observational study design. Of the included publications, 13 articles (59.09%) applied quantitative methodology, 5 (22.72%) qualitative methodology and 4 (18.18%) used mixed methods. In terms of methods, the majority of studies utilised cross-sectional surveys (n = 13; 59.09%) and/or clinical exams (n = 7, 31.18%), and/or in-depth interviews (n = 6, 27.27%). Supplementary Table S 1 presents an overview of the characteristics and scope of the eligible studies.

Thematic analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis to contextualise and understand the elements of FGS integration reported in the eligible studies. The results are presented in two ways. First, we recorded the frequency of each theme. Second, we synthesised the existing opportunities and challenges for FGS integration in relation to each theme.

The analysis revealed two prominent themes, each containing several subthemes. Studies were classified based on their (i) activities and (ii) services and programmes according to the Engels et al.Citation20 adapted model (see ).

Table 2. Thematic Analysis adapted from Engels et al.Citation20

Frequency

The thematic analysis revealed a predominance of FGS integration activities pertaining to awareness (n = 9) and diagnosis (n = 7), primarily connected to schools (n = 8) and HIV (n = 7) services and programmes. Less common activities were treatment and prevention (n = 3), burden assessment (n = 5), and economic evaluation (n = 2) linked with STIs (n = 6), cervical cancer (n = 3), infertility (n = 1), perinatal care (n = 4), migration (n = 1) and WASH (n = 1) services and programmes. A tree map summarises the findings (see ).

All the publications included in our analysis presented multiple themes or sub-themes. The most frequent intersections occurred between “service” and “programmes,” specifically in the context of NTDs and HIV (n = 6). Additionally, there were notable overlaps between “activities” and “programmes,” particularly concerning community engagement and schools (n = 5), as well as between “activities,” specifically community engagement and awareness (n = 8). For a comprehensive breakdown of how each paper was categorised within these themes and sub-themes, please refer to supplementary Table S1.

Challenges and opportunities for FGS integration

The existing scientific research literature was limited in terms of interventions integrating FGS into SRHR or NTD activities, programmes, or services. For this section, we summarised the challenges and opportunities for FGS integration based on the studies’ results and recommendations of the various studies and their connections with the themes. Therefore, this section is organised by activities while the services and programmes description is presented interchangeably. summarises the challenges and opportunities for FGS integration identified in the literature.

Table 3. Summary of challenges and opportunities for FGS integration identify in the literature

Awareness and community engagement

Challenges

Kukula and colleaguesCitation30 highlighted in their results, the lack of awareness of FGS among the affected communities and health care workers in Ghana. Specifically, their study showed that (i) FGS and urogenital schistosomiasis is assumed and perceived by the community to afflict more males than females, (ii) there is a misunderstanding that FGS and schistosomiasis are often incorrectly assumed to be sexually transmitted and, therefore, commonly misdiagnosed as an STI due to the lack of knowledge and awareness by health care workers, and (iii) girls and women reporting urogenital symptoms assumed to be an STI were often stigmatised by health workers. As a result, women and girls do not seek care at standard health clinics because of the stigma associated with STIs. Those same challenges were also identified by Lothe and colleaguesCitation31 and Mazigo and colleagues.Citation32

In contrast, a study from Tanzania targeting school-aged childrenCitation33 showed that the majority of the participants (n = 69; 74%) had heard about urinary schistosomiasis, and most of them had learned about it in school (n = 83; 90%). Even though they were aware, girls still maintained recreational or domestic contact with infested waterbodies resulting in continued exposure risk to S. haematobium. Similarly, Lothe and colleaguesCitation31 and Mazigo and colleaguesCitation32 showed that MDA campaigns at school are the first contact girls have with information about schistosomiasis, although they also highlighted the gap in knowledge about urogenital schistosomiasis consequences. Likewise, Mutsaka-Makuvaza and colleaguesCitation34 indicate that women of reproductive age in Zimbabwe were aware about urogenital schistosomiasis, but had inadequate knowledge about the mode of transmission, preventive measures, and the associated health consequences.

Opportunities

There is consensus in the literature on the need to raise awareness and sensitise communities, health providers and SRH stakeholders on FGS and its links to HIV, cervical cancer, infertility, and other sexual and reproductive ill-health.Citation30,Citation31,Citation34 Recommendations from the literature cover three main areas to target integration to increase awareness: communities in schistosomiasis endemic (S. haematobium) areas, health care workers, and health service delivery systems.

For the first, Mazigo and colleaguesCitation32 point to the need for FGS awareness programmes that link what people know about schistosomiasis to FGS. Lothe and colleaguesCitation31 advocate for the inclusion of teachers and schools in health education as key to overcoming barriers to treatment and break the cycle of reinfection and stigma related to FGS. Second, health care workers, Kukula and colleaguesCitation30 highlight the need for updating nursing and other health professional training curricula to include FGS in relation to schistosomiasis, other NTDs and SRH. Lastly, studies strongly encourage an integrated approach to health service delivery that includes FGS in the broader symptomatic and clinical management of SRH.Citation30,Citation31,Citation34

Diagnosis

Challenges

An Italian retrospective study with African migrants in Italy reported that urogenital schistosomiasis is not routinely screened for in migrants.Citation35 Numerous studies addressed the performance of parameters to diagnose FGS in several points during the delivery of health services including perinatal care facilities,Citation36 home-based self-swab for FGS,Citation37 testing in the agricultural community settingCitation4 and linking diagnosing FGS and cervical dysplasia.Citation28,Citation38 The challenge related to all these studies is their scope. The majority aimed to assess sensitivity, specificity, acceptability, and predictive values for diagnostic tests for FGS. This narrow focus leaves a gap related to the evidence and pathways for the inclusion of any of these diagnostic tools for FGS among the wider SRH package of interventions.

Opportunities

There is consensus in the literature on (i) the need to develop effective, sensitive and affordable tools to diagnose FGS and (ii) that diagnosing FGS has the benefit of identifying and treating women’s overall reproductive health morbidities.Citation39 Recommendations from the literature cover two main areas: integration into SRHR services and integration into health services targeted at migrant populations from endemic areas.

Two studies with women of child-bearing age in Zambia that investigated home-based self-sampling for FGS suggest a high probability of success for this approach on providing a non-clinical exam and non-clinic option for detection of cases. This opens a pathway towards providing a wider, integrated package of home-based SRHR interventions – HIV, STIs, HPV testing, self-injectable hormonal contraception – together with FGS self-testing.Citation28,Citation37 Rafferty and colleaguesCitation38 further corroborate the rationale of integration. Their study demonstrated that simultaneously screening for cervical dysplasia and FGS using visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) was feasible with the routine resources available in a community in Zambia. This approach can help increase the detection of both FGS and cervical cancer, representing an opportunity for the diagnosis and treatment of two important gynaecological conditions at a single clinic visit.

Treatment & prevention

Challenges

Currently, the primary intervention for prevention of FGS is MDA with praziquantel conducted by NTD programmes in endemic countries. However, gaps and challenges exist in effectively integrating FGS into these programmes. For example, a study investigating knowledge and perceptions and understanding of FGS community members and health providers in Ghana showed that adults and health care workers were worried about the limitations of relying on MDA of praziquantel to school-age children as it does not address the continued risk of exposure in women outside of school-age. They also showed concern about the lack of clarification and information on urogenital schistosomiasis during the campaigns in schoolsCitation30 suggesting a lack of communication by NTD programmes of the role the MDA plays in the prevention of FGS. The study by Person and colleagues,Citation40 in Tanzania corroborates this assessment and builds on it by evaluating the motivations among school-age boys and girls in swallowing the MDA tablets. The study then exposed students to a set of health education and behaviour change (HEBC) interventions and interviewed them again. The researchers found that students were more willing to participate in the MDA once they were shown visual materials with images of the actual blood fluke, therefore, challenging the social norm that it is “normal” to live with worms. Flukes were perceived as dangerous, while worms were seen as the norm.

Opportunities

There is consensus in the literature that MDA should be annually recommended for primary and secondary students to prevent FGSCitation40,Citation41 and to contribute further to decrease the burden of HIV within the population of adolescent girls and young women ages 15–24.Citation30,Citation41 Furthermore, studies also recommend expanding the MDA programme beyond schools to providing praziquantel to women of all ages to prevent and treat FGS; not only to treat and prevent the SRH sequelae of FGS but also as a novel HIV and cervical cancer prevention tool.Citation4,Citation30,Citation42 A study also recommended health education and interventions based on social and behavioural science as key to increase uptake of praziquantel and decrease risk behaviours.Citation40 Lastly, in the context of MDA for school-aged children only, HIV, cervical cancer screening, or other SRH services may represent an avenue for addressing the gap in prevention and treatment for women outside of school-age.

Burden assessment

Challenges

Few studies in the review assessed the community-level burden of FGS. They measured prevalence of pregnancy, HIV, STIs, and FGS among sexually-active, school-attending young women,Citation41,Citation43 subfertility rates among sexually-active womenCitation44 and STI infections in urogenital schistosomiasis endemic areas.Citation45 Among the challenges was the acknowledgement of the difficulty and limitations of diagnosing FGS and therefore accurately measuring the true burden. Current approaches to diagnosis are limited and often result in a significant under-estimation of the disease and its sequelae.

Opportunities

Studies agree that measures of prevalence and burden are key to inform policy making, health financing, effective public health interventions, and timely programmatic decision-making.Citation41,Citation43–45 Studies indicate FGS inclusion in comprehensive sex education, family planning and sexual health programming for adolescent girls and young women may be a good entry point. This is supported by the link between receiving praziquantel before age 21 and potential positive impact on fertility/subfertility and evidence of improved outcomes with treatment in early stages of schistosomiasis infection reported by a pilot study in sexually-active women in Kenya.Citation44 Moreover to improve outcomes, studies advocated for early anti-schistosomal treatment, support for programmes that provide universal treatment of children in S. haematobium endemic regions with praziquantel and improvement of diagnostic tools for FGS.Citation41,Citation43–45

Economical evaluation

Challenges

Two studies evaluated the potential economic impact of integration within WASH and within HIV/AIDS interventions. This review did not identify research aiming to assess the impact/economic evaluation of integrating FGS into infertility and HPV/cervical cancer services. A longitudinal retrospective study in South Africa assessed the impact of the scale-up of piped water on the risk of urogenital schistosomiasis.Citation46 The authors found that for every 1% increase in the coverage of community piped water there is a 2.5% decrease in the odds of infection with S. haematobium. However, the study did not investigate the impact of this intervention on FGS, since it was beyond the scope of the study. Mbah and colleagues,Citation47 on the other hand, assessed the potential effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of praziquantel as a novel intervention strategy against HIV infection in Zimbabwe. The cost-effectiveness model analysis showed that annual mass administration of praziquantel administration to school-age children in Zimbabwe, which would reduce the enhanced risk of HIV transmission per sexual act due to FGS, could result in net savings of US$16–101 million over a 10-year period compared with no mass treatment of schistosomiasis. The main limitation of the study is that it is a model analysis, and not based on observed implementation of the intervention. More data would improve the model outcomes and generalisability.

Opportunities

The recommendation from both studies includes a set of public health efforts to expand and evaluate cost-effective control and integration strategies. Both studies argue that integration may decrease the cost-burden on the health system. Mbah and colleaguesCitation47 argue that mass preventive chemotherapy with praziquantel may be a cost-effective and cost-saving solution in preventing HIV in S. haematobium-endemic areas.

Discussion

This scoping review has investigated how FGS can be integrated into HIV/SRH and NTD programmes and services. In summary, we found several significant gaps in the scientific research literature. The studies mainly described the opportunities and challenges for integration rather than reporting on the results from implementation of integrated interventions. This suggests that there remains a need to pilot and evaluate interventions that integrate FGS into SRH services or other health delivery platforms. Addressing this gap in FGS-related research could build the evidence base for integration of FGS within SRHR programmes and services to improve awareness, catalyse uptake, and better address the burden of FGS. Eligible studies focused on a limited set of countries, study designs, study populations, and reproductive health topics. Of note, most studies were conducted in anglophone Africa, especially South Africa and Tanzania, were observational and cross-sectional in nature, and published in journals with an NTD or infectious diseases scope.

We will discuss the main finding in three ways. First, we will consider rationale for integration highlighted by the included studies and examine the limitations of the integration model used in this review. Second, we will discuss the constraints of the studies included in this review and highlight research gaps and needs to build the evidence for integration. Lastly, we will present recommendations as to how FGS could be integrated into SRHR and NTD programmes and services.

Integration

We found consensus within the studies analysed on the need for integration. Other reviews of the literature on FGS examined the association between FGS and HIV, diagnostic tools, and health education interventions.Citation14,Citation23,Citation24 These reviews advocate and argue for embedding FGS services into existing NTD and SRHR programmes. In addition, policy documents have urged integrating FGS into NTD and SRH services and programmes and into medical curricula.Citation48–51 This seems self-evident and aligned with current NTD and broader primary health care strengthening strategies that support well-integrated care, treating the whole patient and not-siloed programmes. Furthermore, the academic community has advocated for FGS to be acknowledged cross sectionallyCitation7,Citation9,Citation52 across health services for women and girls. Therefore, the remaining gap is around implementation of integrated programmes and services, as highlighted by this review. In summary, we have found that there is strong evidence and advocacy for integration. The question now is why there has been little to no action. We believe that there are two ways to pivot towards integration: (i) framing the issue of FGS neglect from a human rights perspective and (ii) inclusion of FGS as a critical SRH condition in SRHR normative guidance for policy making, budgetary processes and service delivery at country-level. This also brings the response to FGS into the current context of the WHO NTD 2030 Roadmap and supports Universal Health Coverage and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Research gaps and needs

For the scientific literature on FGS integration to advance, researchers should broaden the focus to include: (i) reproductive health topics, (ii) additional project sites especially in francophone or lusophone Africa, and (iii) impact evaluations of integrated FGS, SRHR, NTD approaches in both service delivery and awareness creation.

Specifically, future studies should address not only HIV/AIDS, as identified in this review, but the full range of reproductive health issues including HPV/cervical cancer, STIs, and family planning including infertility, as per the recommendations of several policy documents from a range of agencies.Citation48–51 Some scholars go further regarding the scope of integration and recommend connecting FGS with menstrual hygiene projects.Citation53 This would further expand and cross-connect WASH interventions with SRHR community engagement initiatives as a possible pathway to address FGS awareness and stigmatisation. Further, additional studies should be conducted, not limited to school-aged children, but also with women of reproductive age, and should present data disaggregated by age. This is of particular importance for women who continue to live in the same schistosomiasis-endemic environment and, therefore, are at constant risk of reinfection and in critical need of treatment.Citation51 Lastly, we found that most of the study sites were conducted in anglophone Africa, even though S. haematobium is known to be endemic throughout the African continent and the Middle East and North Africa region.Citation39,Citation54 More research is needed to uncover the burden of FGS in these areas and investigate the knowledge, perspectives, practice, and attitudes towards FGS in those communities and among health care providers.

Most of the methodological design and scope of the studies were clinical investigations aiming to elucidate the diagnostic pathways for FGS.Citation4,Citation28,Citation35–38,Citation42 Yet, as pointed out by Bustinduy and colleagues,Citation23 there is still no standardisation on how to diagnose FGS, clarity on the impact of treatment with praziquantel, or even a case definition for FGS. A clear case definition for FGS across the spectrum of infection and diseases would facilitate improved disease surveillance and management. Still, having clinical clarity is insufficient to tackle the FGS problem.Citation9,Citation20,Citation23 More impact evaluation studies are needed to build the evidence base for integrating FGS within the health system and service delivery platforms directed at women and girls. The latter is indispensable for increasing utilisation of FGS services and, in particular, uptake of treatment.Citation30

Recommendations to ignite action

FGS is a human rights issue as it is strongly associated with gender norms that put women at higher risk of exposure, social stigma related to reproductive issues, and low socioeconomic status which results in barriers to appropriate care.Citation10 The United Nations has outlined the right to health for all persons;Citation55 however, this combination of gender, stigma, and socioeconomic status all contribute to the continued neglect of women and girls with FGS. Therefore, to address FGS, we need to extend actions beyond health delivery. Addressing the burden of FGS is dependent on increasing the recognition of FGS as a risk factor for HIV acquisition, an SRH condition in its own right, a risk factor for reproductive complications, and a critical roadblock to achieving gender equality. This will require funding for sustained advocacy, policy change, integrated programme implementation and scale-up and scientific research to fill critical knowledge gaps and tackle the challenges presented in this review.Citation9,Citation10,Citation20

No single or straightforward action or policy intervention will ultimately work to solve the continued neglect of FGS and women's needs. Therefore, we propose five action areas:

Increase FGS awareness amongst health providers and SRH stakeholders

Sensitise and decrease FGS-associated stigma and include FGS within health education and comprehensive sexuality education curricula

Integrate FGS into the essential package of SRH services

Engage stakeholders to collaborate, learn and take action together on FGS

Continue to build and strengthen the FGS evidence base, including FGS integration interventions

By taking the above actions, we will strengthen comprehensive SRHR and NTD programming through the sustainable integration of FGS. This will ultimately decrease the burden of HIV, cervical cancer, and other SRH issues more broadly through improved differential diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of FGS, decreasing its impact on women’s reproductive health and improving the lives of millions of girls and women.

This study has several limitations. First, the paucity of results of integration studies led us to adopt a “generous” inclusion criterion for the definition of “integration”. Second, we limited our search to empirical peer-review studies, leaving behind several reports, briefs, theses, dissertations, and websites. Third, although the framework from Engels and colleaguesCitation20 is useful in paving the way for concrete actions for FGS integration, the model is limited by its primary focus on health service delivery. Williams and colleaguesCitation10 argue that to address FGS, we must amplify the scope of the problem and “confront the compounding forces of stigma, inequality, and poverty demanding an intersectional human rights response” (p. 6).Citation10 We propose shifting the focus by putting women and girls at the centre of the response, rather than the parasite that causes the condition. A rights-based approach to FGS will address the root causes of poverty and marginalisation which impact access to health services as well as access to safe water and sanitation. Future research should investigate the integration of FGS services within health systems regarding their availability, feasibility, accessibility, and affordability of quality services. Subsequent evidence needs to be published in peer-reviewed journals focused on women's health and embedded into medical training at all levels. Evidence must be translated into programming and operational research for FGS integration. Investments and political will are needed to realise the potential of FGS integration as an HIV prevention innovation.

Conclusion

Integration of FGS into SRHR programming is a practical global health response to this overlooked pathogen. FGS sits clearly within the current context of the WHO NTD 2030 Roadmap and UNAIDS’ Global AIDS strategy, which emphasises integration and cross-sector collaboration as well as supporting overarching Universal Health Coverage and SDG objectives. In addition, responding to FGS goes beyond a clinical health care response; the failure to address FGS is an indicator of the failure of health systems to respond to the needs and rights of women and girls.

In light of this, it is important to acknowledge that this review highlighted an evidence gap on how to integrate FGS most effectively into HIV/SRHR and NTD programmes. Studies mainly described the opportunities and challenges for integration rather than presenting how interventions were conducted and the outcomes achieved. They advocated for integration and the importance of FGS as a significant co-factor for HIV infection and other SRH complications. Recommendations for FGS integration in women's health and related environmental areas included increasing FGS awareness and education among communities, educational institutions and healthcare workers; effectiveness of FGS diagnostic tools; and providing praziquantel to women and girls of all ages and out-of-school children to prevent and treat FGS and as a novel HIV and cervical cancer prevention tool. To ignite action on FGS, research and policy must move beyond service delivery and build a strategy for FGS grounded in the principles of human rights and gender equality. Programmes need more research to guide them in how to do this and meet the needs of women and girls in their programmes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (65.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Wendi Reed for her generous ongoing support to FGS. The authors are grateful for the efforts and support of all FGS Integration Group members.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2262882.

References

- Mbabazi PS, Andan O, Fitzgerald DW, et al. Examining the relationship between urogenital schistosomiasis and hiv infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1396. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001396

- Stothard JR, Stanton MC, Bustinduy AL, et al. Diagnostics for schistosomiasis in Africa and Arabia: a review of present options in control and future needs for elimination. Parasitology. 2014;141:1947–1961. doi:10.1017/S0031182014001152

- Ekpo UF, Odeyemi OM, Sam-Wobo SO, et al. Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) in Ogun State, Nigeria: a pilot survey on genital symptoms and clinical findings. Parasitology Open. 2017;3:e10. doi:10.1017/pao.2017.11

- Poggensee G, Krantz I, Kiwelu I, et al. Screening of Tanzanian women of childbearing age for urinary schistosomiasis: validity of urine reagent strip readings and self-reported symptoms. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78(4):542–548. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid = 2-s2.0-0034091592&partnerID = 40&md5 = fae1150264aefd2fc19615209cd47c40.

- Kjetland EF, Mduluza T, Ndhlovu PD, et al. Genital schistosomiasis in women: a clinical 12-month in vivo study following treatment with praziquantel. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2006;100(8):740–752. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.09.010

- Leutscher PDC, Høst E, Reimert CM. Semen quality in Schistosoma haematobium infected men in Madagascar. Acta Trop 2009;109(1):41–44. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.09.010

- Christinet V, Lazdins-Helds JK, Stothard JR, et al. Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS): from case reports to a call for concerted action against this neglected gynaecological disease. Int J Parasitol 2016;46(7):395–404. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.02.006

- Hotez PJ, Harrison W, Fenwick A, et al. Female genital schistosomiasis and HIV/AIDS: reversing the neglect of girls and women. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007025. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007025

- Krentel A, Steben M. A call to action: ending the neglect of female genital schistosomiasis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2021;43(1):3–4. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2020.11.008

- Williams CR, Seunik M, Meier BM. Human rights as a framework for eliminating female genital schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(3):e0010165-9. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010165

- Brodish PH, Singh K. Association between Schistosoma haematobium exposure and human immunodeficiency virus infection among females in Mozambique. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(5):1040–1044. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0652

- Downs JA, Dupnik KM, van Dam GJ, et al. Effects of schistosomiasis on susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and HIV-1 viral load at HIV-1 seroconversion: a nested case-control study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005968. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005968

- Kjetland EF, Leutscher PDC, Ndhlovu PD. A review of female genital schistosomiasis. Trends Parasitol 2012;28(2):58–65. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2011.10.008

- Patel P, Rose CE, Kjetland EF, et al. Association of schistosomiasis and HIV infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:544–553. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.088

- Dupnik KM, Lee MH, Mishra P, et al. Altered cervical mucosal gene expression and lower interleukin 15 levels in women with Schistosoma haematobium infection but not in women with Schistosoma mansoni infection. J Infect Dis. 2019;219(11):1777–1785. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy742

- Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, et al. Association between genital schistosomiasis and HIV in rural Zimbabwean women. AIDS. 2006;20(4):593–600. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000210614.45212.0a

- Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Kurewa EN, et al. Prevention of gynecologic contact bleeding and genital sandy patches by childhood anti-schistosomal treatment. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008;79(1):79–83. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2008.79.79

- Richter J, Poggensee G, Kjetland EF, et al. Reversibility of lower reproductive tract abnormalities in women with Schistosoma haematobium infection after treatment with praziquantel — an interim report. Acta Trop 1996;62(4):289–301. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(96)00030-7

- World Health Organization. Female genital schistosomiasis: a pocket atlas for clinical health-care professionals. Who/Htm/Ntd/2015.4; 2015(September 1), p. 49. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/180863/1/9789241509299_eng.pdf.

- Engels D, Hotez PJ, Ducker C, et al. Integration of prevention and control measures for female genital schistosomiasis, HIV and cervical cancer. Bull World Health Organ 2020;98(9):615–624. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.252270

- Hontelez JAC, Bulstra CA, Yakusik A, et al. Evidence-based policymaking when evidence is incomplete: the case of HIV programme integration. PLoS Med 2021;18(11):e1003835-7. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003835

- Waite RC, Velleman Y, Woods G, et al. Integration of water, sanitation and hygiene for the control of neglected tropical diseases: a review of progress and the way forward. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl_1):ii22–ii27. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihw003

- Bustinduy AL, Randriansolo B, Sturt AS, et al. An update on female and male genital schistosomiasis and a call to integrate efforts to escalate diagnosis, treatment and awareness in endemic and non-endemic settings: the time is now. In Rollinson D, Stothard R, editors. Advances in parasitology. London: Academic Press; 2022.

- Price A, Verma A, Welfare W. Are health education interventions effective for the control and prevention of urogenital schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015;109(4):239–244. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trv008

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:1–7. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Sturt AS, Webb EL, Phiri CR, et al. Genital self-sampling compared with cervicovaginal lavage for the diagnosis of female genital schistosomiasis in Zambian women: The BILHIV study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):e0008337-18. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008337

- Goodwin N. Discharge planning: screening older patients for multidisciplinary team referral. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16(4):1–4. doi:10.5334/ijic.2252

- Kukula VA, MacPherson EE, Tsey IH, et al. A major hurdle in the elimination of urogenital schistosomiasis revealed: identifying key gaps in knowledge and understanding of female genital schistosomiasis within communities and local health workers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(3):e0007207-14. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007207

- Lothe A, Zulu N, Øyhus AO, et al. Treating schistosomiasis among South African high school pupils in an endemic area, a qualitative study. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3102-0

- Mazigo HD, Samson A, Lambert VJ, et al. “We know about schistosomiasis but we know nothing about FGS”: a qualitative assessment of knowledge gaps about female genital schistosomiasis among communities living in Schistosoma haematobium endemic districts of Zanzibar and Northwestern Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009789. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009789

- Lillerud LE, Stuestoel VM, Hoel RE, et al. Exploring the feasibility and possible efficacy of mass treatment and education of young females as schistosomiasis influences the HIV epidemic. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2010;281(3):455–460. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1108-y

- Mutsaka-Makuvaza MJ, Matsena-Zingoni Z, Tshuma C, et al. Knowledge, perceptions and practices regarding schistosomiasis among women living in a highly endemic rural district in Zimbabwe: implications on infections among preschool-aged children. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:1–15. doi:10.1186/s13071-019-3668-4

- Beltrame A, Guerriero M, Angheben A, et al. Accuracy of parasitological and immunological tests for the screening of human schistosomiasis in immigrants and refugees from African countries: an approach with latent class analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005593. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005593

- Oyeyemi OT, Odaibo AB. Maternal urogenital schistosomiasis; monitoring disease morbidity by simple reagent strips. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0187433. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187433

- Phiri CR, Sturt AS, Webb EL, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of genital self-sampling for the diagnosis of female genital schistosomiasis: a cross-sectional study in Zambia [version 2; peer review: 2 approved with reservations]. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:61. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15482.2

- Rafferty H, Sturt AS, Phiri CR, et al. Association between cervical dysplasia and female genital schistosomiasis diagnosed by genital PCR in Zambian women. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06380-5

- Talaat M, Watts S, Mekheimar S, et al. The social context of reproductive health in an Egyptian hamlet: a pilot study to identify female genital schistosomiasis. Social Sci Med. 2004;58(3):515–524. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.018

- Person B, Rollinson D, Ali SM, et al. Evaluation of a urogenital schistosomiasis behavioural intervention among students from rural schools in Unguja and Pemba Islands, Zanzibar. Acta Trop 2021;220:105960. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.105960

- Livingston M, Pillay P, Zulu SG, et al. Mapping Schistosoma haematobium for novel interventions against female genital schistosomiasis and associated HIV risk in Kwazulu-natal, South Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104(6):2055–2064. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0679

- Norseth HM, Ndhlovu PD, Kleppa E, et al. The colposcopic atlas of schistosomiasis in the lower female genital tract based on studies in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Madagascar and South Africa, Zimbabwe, Madagascar and South Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(11):e3229. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003229

- Galappaththi-Arachchige HN, Zulu SG, Kleppa E, et al. Reproductive health problems in rural South African young women: risk behaviour and risk factors. Reprod Health. 2018;15:1–10. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0581-9

- Miller-Fellows SC, Howard L, Kramer R, et al. Cross-sectional interview study of fertility, pregnancy, and urogenital schistosomiasis in coastal Kenya: documented treatment in childhood is associated with reduced odds of subfertility among adult women. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006101. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006101

- Yirenya-Tawiah D, Annang TN, Apea-Kubi KA, et al. Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae prevalence among women of reproductive age living in urogenital schistosomiasis endemic area in Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-349

- Tanser F, Azongo DK, Vandormael A, et al. Impact of the scale-up of piped water on urogenital schistosomiasis infection in rural South Africa. ELife. 2018;7:e33065. doi:10.7554/eLife.33065

- Mbah MLN, Kjetland EF, Atkins KE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a community-based intervention for reducing the transmission of Schistosoma haematobium and HIV in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110(19):7952–7957. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221396110

- SCI F. Female genital schistosomiasis – a neglected reproductive health crisis; 2022. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b4cc42f4611a0e9f08711ce/t/6225e5984064863e6e38070a/1646650813493/SCIF_FGS_Position_Paper.pdf.

- UNAIDS. No more neglect female genital schistosomiasis and HIV. Integrating Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions to Improve Women’s Lives; 2019. UNAIDS/JC2979:1–44.

- UNAIDS. Global aids strategy 2021–2026 end inequalities. End Aids. In UNAIDS; 2021. https://www.unaids.org/en/Global-AIDS-Strategy-2021-2026.

- World Health Organisation. Deworming for adolescent girls and women of reproductive age; 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037670.

- Ozano K, Dean L, Yoshimura M, et al. A call to action for universal health coverage: why we need to address gender inequities in the neglected tropical diseases community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0007786. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007786

- Stothard JR, Odiere MR, Phillips-Howard PA. Connecting female genital schistosomiasis and menstrual hygiene initiatives. Trends Parasitol 2020;36(5):410–412. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2020.02.007

- Lai Y-S, Biedermann P, Ekpo UF, et al. Spatial distribution of schistosomiasis and treatment needs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and geostatistical analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(8):927–940. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00066-3

- The right to the highest attainable standard of health, General Comment no 14. (testimony of UN); 2000. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/425041.