Abstract

Increasing rates of mobile phone access present potential new opportunities and risks for adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health in resource-poor settings. We investigated associations between mobile phone access/use and sexual risks in a cohort of 10–24-year-olds in South Africa. 1563 adolescents (69% living with HIV) were interviewed in three waves between 2014 and 2018. We assessed mobile phone access and use to search for health content and social media. Self-reported sexual risks included: sex after substance use, unprotected sex, multiple sexual partnerships and inequitable sexual partnerships in the past 12 months. We examined associations between mobile phone access/use and sexual risks using covariate-adjusted mixed-effects logistic regression models. Mobile phone access alone was not associated with any sexual risks. Social media use alone (vs. no mobile phone access) was associated with a significantly increased probability of unprotected sex (adjusted average marginal effects [AMEs] + 4.7 percentage points [ppts], 95% CI 1.6–7.8). However, health content use (vs. no mobile phone access) was associated with significantly decreased probabilities of sex after substance use (AMEs –5.3 ppts, 95% CI –7.4 to –3.2) and unprotected sex (AMEs –7.5 ppts, 95% CI –10.6 to –4.4). Moreover, mobile phone access and health content use were associated with increased risks of multiple sexual partnerships in boys. Health content use was associated with increased risks of inequitable sexual partnerships in adolescents not living with HIV. Results suggest an urgent need for strategies to harness mobile phone use for protection from growing risks due to social media exposure.

Résumé

Des taux croissants d’accès aux téléphones portables offrent de nouvelles occasions et créent de nouveaux risques potentiels pour la santé sexuelle et reproductive des adolescents dans les environnements à faibles ressources. Nous avons étudié les associations entre l’accès/l’utilisation du téléphone portable et les risques sexuels dans une cohorte de jeunes âgés de 10 à 24 ans en Afrique du Sud. 1563 adolescents (dont 69% vivaient avec le VIH) ont été interrogés en trois vagues entre 2014 et 2018. Nous avons évalué l’accès et l’utilisation du téléphone portable pour rechercher des contenus sur la santé et les médias sociaux. Les risques sexuels autodéclarés comprenaient: les rapports sexuels après consommation de drogues, les rapports sexuels non protégés, les partenariats sexuels multiples et les partenariats sexuels inéquitables au cours des 12 mois précédents. Nous avons examiné les associations entre l’accès/l’utilisation du téléphone portable et les risques sexuels à l’aide de modèles de régression logistique à effets mixtes ajustés en fonction des covariables. L’accès au téléphone portable à lui seul n’était associé à aucun risque sexuel. L’utilisation des médias sociaux seule (par rapport à l’absence d’accès au téléphone portable) était associée à une probabilité significativement accrue de relations sexuelles non protégées (effets marginaux moyens ajustés [AME] + 4,7 points de pourcentage, IC 95% 1,6 à 7,8). Néanmoins, l’utilisation de contenus liés à la santé (par rapport à l’absence d’accès au téléphone portable) était associée à une diminution significative des probabilités d’avoir des rapports sexuels après la consommation de drogues (AME −5,3 points de pourcentage, IC 95% – 7,4 à −3,2) et des relations sexuelles non protégées (AME – 7,5 points de pourcentage, IC 95% – 10,6 à – 4,4). De plus, l’accès à un téléphone portable et l’utilisation de contenus liés à la santé étaient associés à des risques accrus de partenariats sexuels multiples chez les garçons. L’utilisation de contenus liés à la santé était associée à des risques accrus de partenariats sexuels inéquitables chez les adolescents non séropositifs. Les résultats suggèrent un besoin urgent de stratégies visant à exploiter l’utilisation du téléphone portable pour se protéger contre les risques croissants dus à l’exposition aux médias sociaux.

Resumen

El aumento de las tarifas de acceso a teléfonos móviles presenta posibles oportunidades y riesgos nuevos para la salud sexual y reproductiva de adolescentes en entornos con escasos recursos. Investigamos las asociaciones entre la accesibilidad/uso de teléfonos móviles y los riesgos sexuales en una cohorte de jóvenes entre 10 y 24 años, en Sudáfrica. Entre 2014 y 2018, entrevistamos a 1563 adolescentes (el 69% de quienes vivían con VIH) en tres oleadas. Evaluamos la accesibilidad y el uso de teléfonos móviles para buscar contenido sobre salud y las redes sociales. Algunos de los riesgos sexuales informados por las personas entrevistadas eran: sexo después de la toxicomanía, sexo sin protección, múltiples parejas sexuales y parejas sexuales inequitativas en los últimos 12 meses. Examinamos las asociaciones entre la accesibilidad y el uso de teléfonos móviles y los riesgos sexuales utilizando modelos de regresión logística de efectos mixtos ajustados por covariables. El acceso a teléfonos móviles por sí solo no estaba asociado con riesgos sexuales. El uso de las redes sociales por sí solo (vs. ningún acceso a teléfonos móviles) estaba asociado con un aumento significativo en la probabilidad de tener sexo sin protección (efectos marginales promedio ajustados [AME, por sus siglas en inglés] + 4.7 puntos porcentuales [ppts], IC al 95% de 1.6 a 7.8). Sin embargo, el uso de contenido sobre salud (vs. ningún acceso a teléfonos móviles) estaba asociado con una disminución significativa de las probabilidades de tener sexo después de la toxicomanía (AME –5.3 ppts, IC al 95% de 7.4 a 3.2) y sexo sin protección (AME –7.5 ppts, IC al 95% de 10.6 a 4.4). Además, el acceso a teléfonos móviles y el uso de contenido sobre salud estaban asociados con mayor riesgo de niños varones de tener múltiples parejas sexuales. El uso de contenido sobre salud estaba asociado con mayor riesgo de tener parejas sexuales inequitativas entre adolescentes que no vivían con VIH. Los resultados indican la necesidad urgente de formular estrategias para facilitar el uso de teléfonos móviles para la protección de crecientes riesgos por exposición a las redes sociales.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest and fastest-growing youth population, with multiple overlapping sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs.Citation1 In South Africa, the youth population is projected to reach more than 11 million by 2030.Citation2 South African youth experience heightened sexual health risk: most new HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infections occur during adolescence,Citation3,Citation4 and one in three girls become pregnant before age 20.Citation5

Adolescents and young people have been early and enthusiastic adopters of digital technologies. In 2019, 71% of South African households had a mobile phone user, and 64% had access to the internet,Citation6 with youth aged 15–24 years comprising 71% of internet users.Citation7 Recent studies have identified the potential of increasing mobile phone access and use to improve adolescents' and young people’s health.Citation8–11 Mobile health (m-Health) initiatives may be a key pathway to improve SRH knowledge and HIV prevention among young people in resource-limited settings.Citation9,Citation12 Previous studies have shown that m-Health might help prevent adolescents from engaging in risky sexual behaviours as a result of improved SRH knowledge.Citation9,Citation13 Findings from a cluster-randomised control trial among 756 females aged 14–24 years in Accra, Ghana, indicated that text messaging improved their SRH knowledge, which in turn led to decreased risks of pregnancy.Citation14 Most of m-Health interventions were implemented, taking into account the intersections with adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health and rights in both policy and practice.

However, m-Health interventions remain limited in scope and coverage, without proper evidence of large scaling-up process.Citation15 A study on how 4500 young people in Ghana, Malawi and South Africa used mobile phones revealed that the majority of them had never heard of m-Health interventions, let alone participated in them.Citation16 Searches via social media and websites have proven to be an innovative way to engage adolescents.Citation11,Citation17 Qualitative evidence supports user-driven health content use (rather than campaign-driven health content use) as an effective means of improving health behaviours, Citation16–18 but quantitative research, especially related to sexual risk behaviours, is lacking.

This study attempted to close this gap by focusing on the “informal” uses of m-Health – namely guided by creative and strategic use of mobile phones – for safer sexual risk behaviours.Citation16 The paper did not overlook the fact that adolescents are also susceptible to exposure to risks in the online space. A recent meta-analysis showed that frequent use of social media among adolescents is associated with increased risks of drug use, risky sexual practices and violent behaviours.Citation19

We aimed to examine the associations of sexual risk behaviours with access to and use of mobile phones among a cohort of adolescents in South Africa, and to assess these associations by sex and HIV status.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a prospective cohort study “Mzantsi Wakho” amongst 1563 adolescents living with and without HIV in South Africa. This study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement for cohort studies (Appendix 1).Citation20

Study setting and participants

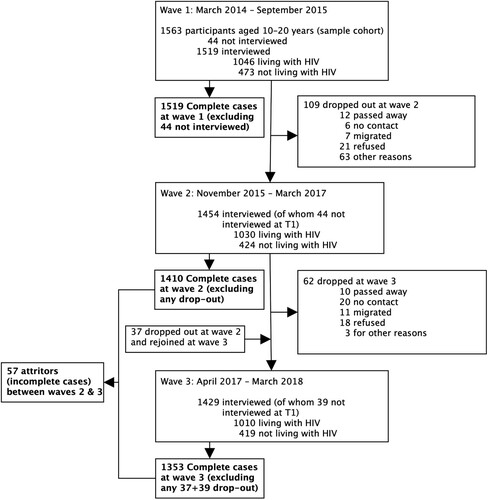

Research was conducted in 180 communities in a health sub-district in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. The Eastern Cape has high levels of poverty and HIV.Citation21 The study recruited adolescents living with HIV from 52 primary healthcare clinics in 2014–2015 and 15 additional clinics in 2016–2018, and then recruited neighbouring adolescents not living with HIV in local communities. In the first wave of Mzantsi Wakho, which commenced in 2014–2015, 1519 adolescents were successfully interviewed, including 1046 living with HIV and 473 not living with HIV (). Wave 2 (1454 interviewed, 1030 of whom were living with HIV; 1410 complete cases) was conducted in 2015–2017 and wave 3 (1429 interviewed, 1010 of whom were living with HIV; 1353 complete cases) in 2017–2018. In waves 2 and 3, participants resided in Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, North-West and Western Cape, due to high levels of migration. Ethical protocols were approved by the University of Cape Town (Cape Town, South Africa; CSSR 2013/4, approved 14 April 2013), Oxford University (Oxford, UK; CUREC2/12-21, approved 20 December 2012), Provincial Departments of Health and Education, and all participating healthcare facilities. All adolescents and their primary caregivers provided written informed consent at all survey rounds in Xhosa or English, and POPIA-compliant data management instruments were used across the data lifecycle to protect the personal information of participants.Citation22

Variables/measures

Study outcomes

Outcomes were four behaviours important for achieving sexual and reproductive health and preventing HIV among adolescents.Citation23–26 All were self-reported for the past 12 months: (1) sex after substance use defined as sexual intercourse when the participant was drunk or used drugs (available in waves 2 and 3); (2) unprotected sex defined as no or infrequent condom use with partners (available in all waves); (3) multiple sexual partnerships defined as two or more sexual partners (available in all waves) and (4) inequitable sexual partnerships defined as sex in exchange for material support of any kind or sexual partner at least 5 years older than participant (available in all waves).

Mobile phone access and use

Self-reported data on current access to and use of mobile phone were available in waves 2 and 3. Adolescents were asked if they had a mobile phone (including a smartphone, Apple iPhone, Blackberry, basic phone and SIM card) and if it was their own or shared with someone. In this study, mobile phone access refers to self-reported ownership of a mobile phone with a functional SIM card. Adolescents who owned a mobile phone reported what they used it for and the frequency of use. Mobile phone use options included SMS, WhatsApp, Facebook, Mixit, health information, information about sexual health and HIV-related information. Frequency of use was reported in the questionnaire as “1. Never”, “2. once a month”, “3. once a week”, “4. once a day” and “5. two or more times a day”. Hereafter, we refer to daily or multiple times daily use as (frequent) use of mobile phone (recoded as binary). Mobile phone use measure was then classified as “0. no access”, “1. social media alone” (referring to frequent mobile phone use for SMS, Facebook, Mixit or WhatsApp only) and “2. health content” (referring to frequent mobile phone use for both social media and sexual health or HIV-related information). Access to and use of mobile phone were measured in waves 2 and 3.

Covariates

We included eight covariates in our models based on associations identified in existing literatureCitation27: rural residence; informal housing; household poverty measured as access to the eight highest socially perceived necessities in the nationally representative South African Social Attitudes Survey (enough food, money for school fees, to see a doctor when needed, school uniform, basic clothing, soap, school books and shoes)Citation28; being married or in a consensual relationship; age; sex; living with HIV; school enrolment and survey wave. All covariates were categorical variables, except for the participant’s age, which was continuous, and mean-centred before analysis to facilitate interpretations. Covariates changed for very few individuals in the data. Therefore, all covariates, except for the survey wave, were measured at baseline (between March 2014 and September 2015).

Data and bias

Participants who dropped out of the study between waves 2 and 3 (n = 57) did not differ systematically from participants who completed both waves (n = 1353) (Appendix 2) suggesting no strong evidence of attrition bias.Citation29–31 Little’s χ2 test, with the presence of covariates and unequal variances between different missing-value patterns, indicated that data were not missing completely at random (Appendix 3).Citation32 Frequencies showed that more missing data occurred in wave 2 than in wave 3. The proportion of missing data on sex after substance use was 13.5% in wave 2 and 6.5% in wave 3; the proportion of missing data on inequitable sexual partnerships ranged from 3.8% in wave 2 to 6.5% in wave 3. There was no missing data on mobile phone access and use (neither in wave 2 nor in wave 3). The amount of missing data for covariates at baseline was 0.1% for household poverty and informal housing. There was no missing data on sex, age, rural residence, relationship status, school enrollment and HIV status. To maximise statistical power while minimising bias, we imputed missing data ten times in wide format using chained equations method.Citation33–35 Imputation models included all aforementioned covariates and auxiliary variables that were predictive of sexual risk behaviours.

Statistical methods

We first described sociodemographic characteristics, mobile phone access and use, individual sexual risk behaviours in the full sample, then by adolescent sex and HIV status. The correlations between individual outcomes were weak or moderate. We reported Spearman’s bivariate correlation coefficients between outcome variables in Appendix 4. We reported the descriptive statistics for the original sample (i.e. data with missing values). Second, we used mixed effects logistic regression models on imputed data to account for repeated measures.Citation36 A summary of the models is reported in Appendix 5. We estimated the overall association of individual sexual risk behaviours with mobile phone access (Model 1) and mobile phone use for social media alone and health content (Model 2), adjusting for baseline covariates. We reported average marginal effects from the models to estimate associations of individual sexual risk behaviours with mobile access and use. We also estimated the separate associations of individual sexual risk behaviours with mobile phone access (Appendix 5, Model 3) and mobile phone use (Appendix 5, Model 4) for two sub-groups: boys and girls, and for adolescents living with and without HIV. To prevent underpowered (stratified) analyses, we estimated average marginal effects (AMEs) in all four combinations (of boys or girls, living with HIV or not) using three-way interaction terms (between participant’s sex, HIV status and mobile phone access/use). Third, we conducted sensitivity analyses, comparing the results in an analysis that included only complete cases (from data with no imputations) to results from imputed data. All analyses were done using Stata 17 Citation37. Statistical significance was defined a priori as p < 0.05.

Results

shows baseline socio-demographic characteristics of participants (n = 1410), access to and use of mobile phones (in waves 2 and 3), and sexual risk behaviours (in waves 2 and 3). 69% of participants recruited at baseline were living with HIV. The baseline mean age of respondents was 13.8 years. 57% were female, 27% resided in a rural area, 18% were living in informal houses and 67% were in poor households. Nearly one-third of the sample was in a relationship and 94% were enrolled in school. In wave 2, about half of participants (50%) had access to a mobile phone (including 43% for boys, 56% for girls, 57% for adolescents not living with HIV and 48% for adolescents living with HIV), 44% used mobile phones for social media alone (including 24% for boys, 41% for girls, 49% for adolescents not living with HIV and 36% for adolescents living with HIV) and only 17% for health content (including 20% for boys, 15% for girls, 8% for adolescents not living with HIV and 21% for adolescents living with HIV). In wave 3, there was a slight increase in the proportion of mobile phone access (53%) including 47% for boys, 65% for girls, 63% for adolescents not living with HIV and 55% for adolescents living with HIV; 34% used mobile phone for social media alone (including 25% for boys, 43% for girls, 55% for adolescents not living with HIV and 45% for adolescents living with HIV) and 23% used mobile phone for health content (including 22% for boys, 24% for girls, 7% for adolescents not living with HIV and 30% for adolescents living with HIV).

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the study population

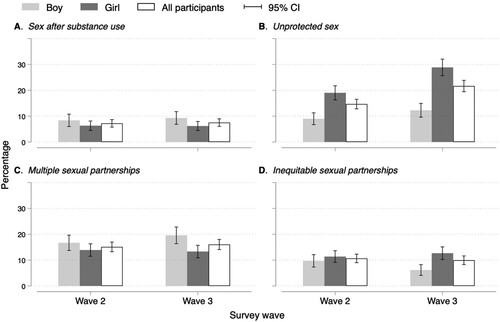

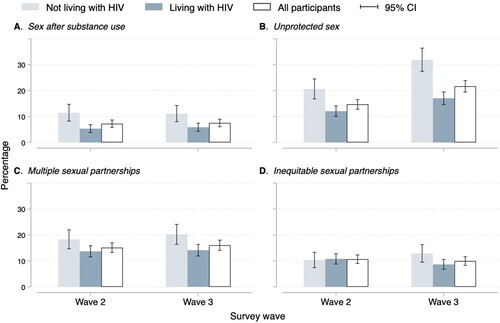

Sexual risk behaviours were similar across waves (), except for unprotected sex which increased from 15% in wave 2 to 22% in wave 3 (B). For boys, there was no change in the prevalence of any of the sexual risk behaviours between waves 2 and 3. For girls, the prevalence of unprotected sex increased from 19% in wave 2 to 29% in wave 3 (B). The proportion of self-reported unprotected sex and sex after substance use was significantly higher among adolescents not living with HIV than among adolescents living with HIV in waves 2 and 3 (A and B). There was a significant increase in the proportion of self-reported unprotected sex between waves 2 and 3 among adolescents not living with HIV (from 21% in wave 2 to 32% in wave 3) and adolescents living with HIV (from 12% in wave 2 to 17% in wave 3) (B). In wave 3, the proportion of self-reported multiple sexual partnerships was higher among adolescents not living with HIV (20%) than among adolescents living HIV (14%) (C).

Figure 2. Sexual risk behaviours by participant's sex across waves. Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval

Figure 3. Sexual risk behaviours by participant's HIV status across waves. Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus . HIV-, adolescents not living with HIV. HIV+, adolescents living with HIV

We fit two multivariable models to determine the association of individual sexual risk behaviours with mobile phone access (, Model 1) and mobile phone use (, Model 2). We found no evidence of an association between mobile phone access and sexual risk behaviours after adjusting for covariates.

Table 2. Multivariable association between mobile phone access and use and self-reported sexual risk behaviours. Results from mixed-effects logistic regression models on ten imputed datasets (n = 1353)

Social media use alone (as compared to no mobile phone access) was associated with a significantly increased probability of unprotected sex (AMEs +4.7 percentage points [ppts], 95% CI 1.6 to 7.8, p = 0.003). Health content use (as compared to no mobile phone access) was associated with a significantly decreased probability of sex after substance use (AMEs –5.3 ppts, 95% CI –7.4 to –3.2, p < 0.001) and decreased probability of unprotected sex (AMEs –7.5 ppts, 95% CI –10.6 to –4.4, p < 0.001).

Then we estimated separate effects of mobile phone access (, Model 3) and mobile phone use (, Model 4) for boys, girls and adolescents living with and without HIV. Mobile phone access was associated with a significantly increased probability of self-reported multiple sexual partnerships among boys only (AMEs 5.5 ppts, 95% CI 1.1–9.6, p = 0.013). In all four categories, adolescents who used mobile phones for health content had significantly lower probabilities of reporting unprotected sex (for boys: AMEs –6.8 ppts, 95% CI –11.4 to –2.2, p = 0.004; for girls: AMEs –7.9 ppts, 95% CI –12.5 to –3.2, p = 0.001; for adolescents not living with HIV: AMEs –10.0 ppts, 95% CI –17.0 to –3.1, p = 0.005; for adolescents living with HIV: AMEs –6.0 ppts, 95% CI –9.4 to –2.6, p = 0.001) than adolescents with no access to a mobile phone. In all four categories except for adolescents not living with HIV, health content use (vs. no mobile phone access) was associated with significantly decreased probabilities of reporting sex after substance use (for boys: AMEs –6.8 ppts, 95% CI –11.5 to –2.2, p = 0.004; for girls: AMEs –3.4 ppts, 95% CI –6.2 to –0.6, p = 0.018; for adolescents living with HIV: AMEs –6.4 ppts, 95% CI –8.7 to –4.1, p < 0.001). Health content use (vs. no mobile phone access) was associated with a significantly increased probability of reporting multiple sexual partnerships for boys only (AMEs 7.6 ppts, 95% CI 1.5–13.7, p = 0.015). Health content use (vs no mobile phone access) was associated with a significantly increased probability of reporting inequitable sexual partnerships for adolescents not living with HIV only (AMEs 8.7 ppts, 95% CI 0.9–16.6, p = 0.029). Social media use of mobile phone (vs. no mobile phone access) was associated with significantly increased probabilities of sex after substance use among boys (AMEs 6.6 ppts, 95% CI 1.2–12.0, p = 0.017) and adolescents living with HIV (AMEs 4.3 ppts, 95% CI 0.7–7.8, p = 0.018). Social media use of mobile phone (vs. no mobile phone access) was associated with significantly increased probabilities of self-reported unprotected sex for girls (AMEs 6.2 ppts, 95% CI 1.8–10.5, p = 0.005) and adolescents living with HIV (AMEs 9.4 ppts, 95% CI 5.3–13.4, p < 0.001).

Table 3. Comparisons of the multivariable association between mobile phone access and use and self-reported sexual risk behaviours for boys, girls, adolescents living with and without HIV. Results from mixed-effects logistic regression models on ten imputed datasets (n = 1353 including 587 boys, 766 girls, 933 living with HIV, and 420 not living with HIV)

We conducted a sensitivity analysis with complete cases and compared to the imputed dataset. The results from the sensitivity analysis and main analysis were similar, confirming overall results (Appendix 6a and 6b).

Discussion

This study provides valuable insight into the rates of mobile phone use alongside sexual risk behaviours of young people who are taking the initiative to “use m-Health” informally, in a high-poverty context in South Africa. We found that 57% of adolescents in our study had access to a mobile phone in 2018; this is consistent with the national average of 55% of mobile phone access in 2019.Citation7 Social media use alone was almost ubiquitous, but less than a quarter of adolescent mobile phone owners had accessed health content in the past 12 months.

Our findings showed no association between mobile phone access and self-reported sexual risk behaviours. However, social media use alone was associated with an increased probability of unprotected sex and sex after substance use among adolescents living with HIV – with consequent risks of HIV exposure for their sexual partners. In contrast, accessing digital content on health or HIV (informal m-Health) – even alongside social media use only – was protective against sexual risk and was associated with lower rates of sex after substance use and unprotected sex.

These findings support and advance the existing literature. Two recent reviews found no associations between access to a mobile phone and adolescent sexual risk, suggesting that access alone to mobile phones is insufficient to improve adolescents’ health outcomes.Citation11,Citation38 Our study supports these conclusions, and additionally examines the relationship amongst a large group of adolescents living with HIV, finding that mobile phone access in itself neither reduces nor increases sexual risks for this group.

Our study found that exclusive use of social media (without concurrent use of health content) is associated with increased unprotected sex. This quantitative evidence adds to qualitative studies and reviews from high-income settings finding that social media use can negatively impact adolescent self-esteem and contribute to high-risk behaviours.Citation39–42 In this South African sample, the increase in unprotected sex amongst adolescents living with HIV and using mobile phones for social media alone suggests that this group may be particularly vulnerable to damaging effects of social media (alone and without access to any health-related information).

Two meta-analyses and a recent systematic review of mobile health interventions report overall benefits for adolescent health behaviours, including sexual health.Citation13,Citation43,Citation44 This study adds to the evidence base by demonstrating beneficial associations of real-world use of health content, in almost all cases alongside social media, amongst adolescents living with and without HIV in South Africa. However, across both waves and in all subgroups, less than a quarter of adolescents had accessed any health content at all on their mobile phones in the past year. This suggests that while health content may be valuable, its uptake amongst this very high-risk group remains low, with consequent need for large-scale interventions that increase access and use of age-appropriate up-to-date sexual and reproductive health intervention. This also includes access to health content via social media.

We note several limitations. First, the use of retrospective self-report measures of sexual risk behaviours may increase bias related to social desirability and recall biases. However, self-report is currently the only feasible way to measure most adolescent sexual risk behaviours. To mitigate measurement errors the study used widely validated measures in previous adolescent sexual health research in South Africa. Second, despite the longitudinal design, causality between the access to and use of mobile phones and sexual risk behaviours cannot be confirmed. Third, although we found no systematic differences between participants who completed both survey rounds and those who dropped out, we cannot fully rule out possible biases from unmeasured sources of confounding and attrition. Other caveats include potential bias due to data not completely missing at random. However, we used multiple imputations to account for biases in missing data. We also repeated the analysis in a sensitivity analysis using complete cases analysis and again found similar results. Fifth, we fit multivariable mixed-effects logistic regression for each outcome separately, therefore, assuming that the covariances among random effects across all sexual risk behaviours outcomes and the covariances among the residuals equal zero. Nevertheless, our findings from sensitivity analyses do not deviate from estimates from multivariable models.

The study also has a number of strengths. It adds to evidence from formal m-Health interventions, by examining a real-life sample of adolescents who use (and do not use) mobile phones informally to improve their SRHR knowledge and how they engage in safer sexual practices. In the absence of large-scale formal m-Health programmes in resource-limited settings, data from informal m-Health can inform development of adolescents’ SRHR and HIV prevention programmes. However, the measure of informal m-Health used in this study is insufficiently detailed to assess the complexity of its associations with adolescents’ sexual risk behaviours. Future surveys should attempt to collect data on mobile phone use in relation to sexual risk behaviours. We collected longitudinal data from adolescents living with and without HIV and analysed a sample of adolescent girls and boys, living with HIV or not, adding to our understanding of informal use of social media and health content amongst and comparing between these important groups.

This study suggests that mobile phones can be a medium of both risk and resilience for adolescents in Southern Africa. Social media use only – without concurrent health content use – was associated with increased sexual risk. Health content use was protective, even in the context of concurrent social media use, but under-utilised. This highlights important next steps for programming: to identify approaches that increase informal m-Health use amongst adolescents and to deliver and assess these in real-world settings. For example, UNICEF and partners have recently proposed a set of toolkits to address sexual and reproductive health and HIV prevention needs.Citation45 As mobile and internet access increases exponentially in Africa over the next decade, it is essential that we minimise associated risks, and capitalise on the potential of mobile phones to improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, William Rudgard, Brendan Maughan-Brown, Janina Jochim, Lucas Hertzog, Alice Armstrong, Lucie Cluver. Data curation: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, William Rudgard, Lucas Hertzog, Janina Jochim, Lucie Cluver. Formal analysis: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, William Rudgard, Janina Jochim, Lucas Hertzog, Lucie Cluver. Funding acquisition: Elona Toska, Lucie Cluver. Methodology: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, William Rudgard, Lucas Hertzog, Janina Jochim, Alice Armstrong, Lucie Cluver. Project administration: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, Lucie Cluver. Supervision: Elona Toska, Lucie Cluver. Validation: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, Lucie Cluver. Visualisation: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Lucie Cluver. Writing – original draft: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, William Rudgard, Brendan Maughan-Brown, Janina Jochim, Lucas Hertzog, Alice Armstrong, Lucie Cluver. Writing – review & editing: Boladé Hamed Banougnin, Elona Toska, William Rudgard, Lucas Hertzog, Lucie Cluver.

Funding statement

This study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement, and by the Department of Health Social Care (DHSC) through its National Institutes of Health Research (NIHR) [MR/R022372/1]; Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa (EHPSA), a UK aid programme managed by Mott MacDonald; Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V., part of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson; the John Fell Fund [161/033]; the Philip Leverhulme Trust [PLP-2014-095]; UCL’s HelpAge funding; the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (n° 771468); the UKRI GCRF Accelerating Achievement for Africa's Adolescents (Accelerate) Hub (Grant Ref: ES/S008101/1); the Fogarty International Center, National Institute on Mental Health, National Institutes of Health under Award Number (K43TW011434 and D43TW011308); a CIPHER grant from International AIDS Society [155-Hod; 2018/625-TOS]; Research England [0005218]; the University of Oxford’s ESRC Impact Acceleration Account [K1311-KEA-004 ]; UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Office (UNICEF-ESARO); the Oak Foundation [OFIL-20-057]; the Nuffield Foundation; the Wellspring Philanthropic Fund [16204]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Nuffield Foundation, or the official policies of the International AIDS Society.

Supplemental Material: Appendices 1-6

Download MS Word (68.8 KB)Data sharing and data availability statement

Prospective users, policymakers/government agencies/researchers (internal/external) will be required to contact the study team to discuss and plan the use of data. Research data will be available on request subject to participant consent and having completed all necessary documentation. All data requests should be sent to the Elona Toska ([email protected]) or William Rudgard ([email protected]).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2267893.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2335088).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yaya, S., Yeboah, H., Udenigwe, O. Demography, development and demagogues. Is population growth good or Bad for economic development? In: F Baqir, S Yaya, editors. Beyond free market. London: Routledge; 2021; p. 109–124.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population prospects 2022, Online Edition. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2022. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/.

- Brown K, Williams DB, Kinchen S, et al. Status of HIV epidemic control among adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years — seven African countries, 2015–2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):29, doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a6

- Khalifa A, Stover J, Mahy M, et al. Demographic change and HIV epidemic projections to 2050 for adolescents and young people aged 15-24. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1662685, doi:10.1080/16549716.2019.1662685

- Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. Prevalence and risk factors of repeat pregnancy among South African adolescent females. Afr J Reprod Health. 2019;23(1):73–87.

- ITU DataHub. ICT statistics and regulatory information [computer software]. International Telecommunication Union (ITU); 2022. https://datahub.itu.int/data/

- ITU. 2020 Measuring digital development Facts and figures 2020. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2020.pdf.

- Grist R, Porter J, Stallard P. Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19(5):e176, doi:10.2196/jmir.7332

- L’Engle KL, Mangone ER, Parcesepe AM, et al. Mobile phone interventions for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160884. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0884

- Logie C, Okumu M, Hakiza R, et al. Mobile health–supported HIV self-testing strategy among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda: protocol for a cluster randomized trial (Tushirikiane, supporting each other). JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(2):e26192. doi:10.2196/26192

- Wong CA, Madanay F, Ozer EM, et al. Digital health technology to enhance adolescent and young adult clinical preventive services: affordances and challenges. J. Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):S24–S33. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.10.018

- Ippoliti NB, L’Engle K. Meet US on the phone: mobile phone programs for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-to-middle income countries. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0276-z

- Onukwugha FI, Smith L, Kaseje D, et al. The effectiveness and characteristics of mHealth interventions to increase adolescent’s use of sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Plos One. 2022;17(1):e0261973. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0261973

- Rokicki S, Cohen J, Salomon JA, et al. Impact of a text-messaging program on adolescent reproductive health: a cluster–randomized trial in Ghana. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):298–305. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303562

- Istepanian RSH. Mobile health (m-health) in retrospect: The known unknowns. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):Article 7. doi:10.3390/ijerph19073747

- Hampshire K, Porter G, Owusu SA, et al. Informal m-health: How are young people using mobile phones to bridge healthcare gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa? Soc Sci Med. 2015;142:90–99. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.033

- Anstey Watkins JOT, Goudge J, Gómez-Olivé FX, et al. Mobile phone use among patients and health workers to enhance primary healthcare: a qualitative study in rural South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2018;198:139–147. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.011

- Perry RCW, Kayekjian KC, Braun RA, et al. Adolescents’ perspectives on the Use of a text messaging service for preventive sexual health promotion. J. Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):220–225. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.012

- Savoia E, Harriman NW, Su M, et al. Adolescents’ exposure to online risks: gender disparities and vulnerabilities related to online behaviors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5786, doi:10.3390/ijerph18115786

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–1499. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013

- Fransman T, Yu D. Multidimensional poverty in South Africa in 2001–16. Dev South Afr. 2019;36(1):50–79. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2018.1469971

- Hertzog L, Wlttesaele C, Titus R, et al. Seven essential instruments for POPIA compliance in research involving children and adolescents in South Africa. S Afr J Sci 2021;117(9–10):1–5.

- Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Campeau L, et al. Improving lives by accelerating progress towards the UN sustainable development goals for adolescents living with HIV: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;3(4):245–254. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30033-1

- Gilbert LK, Annor FB, Kress H. Associations between endorsement of inequitable gender norms and intimate partner violence and sexual risk behaviors among youth in Nigeria: violence against children survey, 2014. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(11–12):NNP8507–NNP8533. doi:10.1177/0886260520978196

- Neville SE, Saran I, Crea TM. Parental care status and sexual risk behavior in five nationally-representative surveys of sub-Saharan African nations. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):59, doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12437-6

- Ziraba A, Orindi B, Muuo S, et al. Understanding HIV risks among adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: lessons for DREAMS. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0197479, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197479

- Svensson P, Sundbeck M, Persson KI, et al. A meta-analysis and systematic literature review of factors associated with sexual risk-taking during international travel. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2018;24:65–88. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.03.002

- Roberts B, Kivilu Mw, Davids YD. South African social attitudes: 2nd report: reflections on the age of hope. (South African social attitudes survey (SASAS)). HSRC Press; 2010. https://repository.hsrc.ac.za/handle/20.500.11910/4120

- Biele G, Gustavson K, Czajkowski NO, et al. Bias from self selection and loss to follow-up in prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34(10):927–938. doi:10.1007/s10654-019-00550-1

- Nohr EA, Liew Z. How to investigate and adjust for selection bias in cohort studies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(4):407–416. doi:10.1111/aogs.13319

- Saiepour N, Najman JM, Ware R, et al. Does attrition affect estimates of association: a longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;110:127–142. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.12.022

- Li C. Little’s test of missing completely at random. Stata J. 2013;13(4):795–809. doi:10.1177/1536867X1301300407

- Byrne A, Shlomo N, Chandola T. Multilevel modelling approach to analysing life course socioeconomic status and understanding missingness. Rev Evolut Politic Econ. 2023;4:275–297. doi:10.1007/s43253-022-00081-8

- Tan FES, Jolani S, Verbeek H. Guidelines for multiple imputations in repeated measurements with time-dependent covariates: A case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;102:107–114. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.06.006

- Vidotto D, Vermunt JK, Van Deun K. Multiple imputation of longitudinal categorical data through Bayesian mixture latent Markov models. J Appl Stat. 2020;47(10):1720–1738. doi:10.1080/02664763.2019.1692794

- Monsalves MJ, Bangdiwala AS, Thabane A, et al. LEVEL (logical explanations & visualizations of estimates in linear mixed models): recommendations for reporting multilevel data and analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):3, doi:10.1186/s12874-019-0876-8

- StataCorp. 2021 Stata Statistical Software: Release 17 [Computer software].

- Liverpool S, Mota CP, Sales CM, et al. Engaging children and young people in digital mental health interventions: systematic review of modes of delivery, facilitators, and barriers. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(6):e16317, doi:10.2196/16317

- Cookingham LM, Ryan GL. The impact of social media on the sexual and social wellness of adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(1):2–5. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2014.03.001

- Dunne A, McIntosh J, Mallory D. Adolescents, sexually transmitted infections, and education using social media: A review of the literature. J Nurse Pract. 2014;10(6):401–408.e2.e2. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.03.020

- Eleuteri S, Saladino V, Verrastro V. Identity, relationships, sexuality, and risky behaviors of adolescents in the context of social media. Sex Relation Ther. 2017;32(3–4):354–365. doi:10.1080/14681994.2017.1397953

- Romo DL, Garnett C, Younger AP, et al. Social media Use and its association with sexual risk and parental monitoring among a primarily hispanic adolescent population. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(4):466–473. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2017.02.004

- Fedele DA, Cushing CC, Fritz A, et al. Mobile health interventions for improving health outcomes in youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(5):461–469. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0042

- Yang Q, Van Stee SK. The comparative effectiveness of mobile phone interventions in improving health outcomes: meta-analytic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(4):e11244, doi:10.2196/11244

- UNICEF ESARO, Y+ Global, & UNFPA ESARO. HIV & SRHR SBC toolkit for adolescents and young people in ESA region. UNICEF. 2021. https://www.unicef.org/esa/documents/hiv-srhr-sbc-toolkit.

Appendices

Appendix 1: STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cohort studies

Appendix 2: Comparison between participants interviewed in both waves (2 and 3) and those who dropped out of the study (between wave 2 and 3)

Appendix 3: Missing data imputations

Appendix 4: Spearman’s bivariate correlation coefficients (95% CI; p-value) between outcome variables. Below the diagonal (value 1) are between-participants correlations and above the diagonal are within-participants correlations

Appendix 5: Summary of statistical models

Appendix 6a: Sensitivity analyses. Multivariable association between mobile phone access and use and self-reported sexual risk behaviours. Results from mixed-effects logistic regression models on complete cases

Appendix 6b: Sensitivity analyses. Comparisons of the multivariable association between mobile phone access and use and self-reported sexual risk behaviours for boys, girls, adolescents living with and without HIV. Results from mixed-effects logistic regression models on complete cases