Abstract

Deeply rooted cultural beliefs and norms relating to the position and the responsibilities assigned to men and women play a significant role in propagating intimate partner violence (IPV). It is yet to be understood in what ways experiences of IPV contribute to how people socially construct their health and wellbeing as they navigate the tensions created by the prevailing sociocultural systems. To address this knowledge gap, we employed a social constructionist perspective and the eco-social model to explore how Kenyans aged 25–49 years socially construct their health and wellbeing in relation to their experiences of IPV. We conducted nine in-depth interviews and ten focus group discussions in four counties in Kenya between January and April of 2017. Textual analysis of the narratives reveals that although men are usually framed as perpetrators of violence, they may also be victims of reciprocal aggression by women, as recently witnessed in cases where women retaliate through gang attacks, chopping of male genitalia, and scalding with water. However, women are still disproportionately affected by gender-based violence because of the deeply rooted gender imbalances in patriarchal societies. Women experience social stigma associated with such violence and when separated or divorced in situations of unsafe relationships, they are viewed as social misfits. As such, most women opt to stay in unhealthy relationships to avoid social isolation. These experiences are not only unhealthy for their psychological wellbeing but also for their physical health and socioeconomic status and that of their offspring.

Résumé

Des normes et croyances culturelles profondément enracinées relatives à la position et aux responsabilités assignées aux hommes et aux femmes jouent un rôle important dans la propagation de la violence exercée par un partenaire intime (VPI). On ignore encore comment l’expérience de la VPI contribue à la façon dont les personnes construisent socialement leur santé et leur bien-être alors qu’elles affrontent les tensions créées par les systèmes socioculturels dominants. Pour combler ce manque de connaissances, nous avons utilisé une perspective constructionniste sociale et le modèle éco-social pour explorer comment les Kenyans construisent socialement leur santé et leur bien-être en rapport avec l’expérience de la VPI chez des Kenyans âgés de 25 à 49 ans. Entre janvier et avril 2017, nous avons mené neuf entretiens approfondis et dix discussions de groupe dans quatre comtés du Kenya. L’analyse textuelle des récits révèle que, même si les hommes sont généralement présentés comme les auteurs des violences, ils peuvent également être victimes d’agressions réciproques de la part des femmes, comme on l’a vu récemment dans des affaires où des femmes ont riposté en organisant des attaques de gangs, en coupant les organes génitaux des hommes ou en les brûlant avec de l’eau bouillante. Néanmoins, les femmes sont encore touchées de manière disproportionnée par les violences sexistes en raison des déséquilibres de genre profondément enracinés dans les sociétés patriarcales. Les femmes subissent une stigmatisation sociale associée à de telles violences et quand elles sont séparées ou divorcées dans des situations de relations dangereuses, elles sont considérées comme asociales. C’est pourquoi la plupart des femmes préfèrent rester dans des relations malsaines pour éviter l’isolement social. Ces expériences sont non seulement nocives pour leur bien-être psychologique, mais aussi pour leur santé physique, leur situation socioéconomique et celle de leur progéniture.

Resumen

Las creencias y normas culturales profundamente arraigadas con relación a la posición y las responsabilidades asignadas a hombres y mujeres desempeñan un papel significativo en propagar la violencia de pareja íntima (VPI). Aún está por entenderse cómo las experiencias de VPI contribuyen a la manera en que las personas construyen socialmente su salud y bienestar a medida que navegan las tensiones creadas por los sistemas socioculturales predominantes. Para subsanar esta brecha de conocimiento, empleamos una perspectiva construccionista social y el modelo ecosocial para explorar cómo las personas kenianas construyen socialmente su salud y bienestar con relación a las experiencias de VPI entre personas de 25 a 49 años. Realizamos nueve entrevistas a profundidad y diez discusiones en grupos focales en cuatro condados de Kenia, entre enero y abril de 2017. El análisis textual de las narrativas revela que, aunque los hombres generalmente son acusados de perpetradores de violencia, también pueden ser víctimas de agresión recíproca de las mujeres, como se observó recientemente en casos en que las mujeres toman represalias con ataques de pandillas, cortando los genitales del hombre y escaldando con agua. Sin embargo, las mujeres continúan siendo afectadas de manera desproporcionada por violencia de género debido a los desequilibrios de género profundamente arraigados en sociedades patriarcales. Las mujeres sufren estigma social asociado con ese tipo de violencia y cuando se separan o divorcian en situaciones de relaciones inseguras, son vistas como inadaptadas sociales. Por ello, la mayoría de las mujeres optan por permanecer en relaciones malsanas para evitar aislamiento social. Estas experiencias no solo son dañinas para su bienestar psicológico, sino también para su salud física y su condición socioeconómica y la de sus hijos.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a leading global human rights violation and a source of morbidity and mortality for women and girls in the world.Citation1 It is estimated that, globally, over 30% of women experience some physical and/or sexual violence by a partner or from someone other than a partner in their lifetime, contributing to serious health repercussions.Citation2,Citation3 Although women and girls disproportionately bear the burden, IPV cuts across race, socioeconomic class, age, geography, and gender and the associated health impacts are immediate and long-term.Citation3,Citation4

Violence by an intimate partner causes not only physical injuries but also mental trauma and psychosocial health problems, including depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and alcohol and drug abuse,Citation3,Citation5 and thence the social connections of those who experience it. Additionally, this kind of violence has been associated with increased vulnerability to STIs including HIV as well as neurological health effects and sexual and reproductive health issues, particularly among women and girls.Citation1,Citation3,Citation6 The effects can be long term and childhood experiences of violence in the home are associated with high-risk behaviours, such as smoking, unsafe sexual practices, and engagement in violent and criminal activities.Citation1,Citation4

Defined as physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviour that causes physical, sexual, and psychological harm, IPV is a complex social issue deeply rooted in the social and cultural norms and structures that perpetuate gender inequality in most societies.Citation6 As such, perceptions, definitions, and prevalence of IPV vary from place to place.Citation1 Evidence shows that societies that are gender-unequal are more likely to experience higher prevalence rates of IPV and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV).Citation6–8 For example, in most lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as in sub-Saharan Africa, where most societies are patriarchal, and the majority of people live in poverty, the frequency of IPV is often relatively high.Citation6,Citation9,Citation10 In Kenya, for example, over half of rural women experience IPV in their lifetime with at least four in every 10 ever-married women between 15–49 years experiencing physical and/or sexual abuse.Citation6,Citation10–12 The recently released Kenya Demographic Health Survey.Citation12 reported that at least 13% of women in Kenya experience sexual violence at some point in their life, with the most commonly reported perpetrators of violence among women who have ever been married or ever had intimate partners being the current husbands or intimate partners (71%) and former husbands. Similarly, among married or ever-married men, the most common perpetrators of violence were reported as being the current wives or intimate partners (63%) and former wives or intimate partners (32%).Citation12

A number of factors at individual and societal level increase women’s risk of sexual violence in Kenya.Citation6,Citation9,Citation10 Studies have associated sexual violence with poverty, alcohol use by partner, being in a polygamous marriage, age difference, employment status, being a Christian, household size, education level, and over-control by a partner.Citation6,Citation7,Citation12,Citation13 In Kenya, most societies are patriarchal, as men are socialised to be family heads and women to be submissive to their leadership. As such, violence is adopted in most communities as a punishment to women who deviate from the traditional and societal roles assigned to each gender.Citation6 Men are viewed as being superior and always right and a woman who questions or engages in an argument with her husband may be viewed as being disrespectful and to be challenging his masculinity, leading the husband to reaffirm his societal position through violence.Citation1 Many Kenyan women are therefore socialised to tolerate partner violence as a norm.Citation6,Citation9,Citation10 Most of the survivors avoid disclosure for fear of being stigmatised by the community, desire to maintain social networks, holding onto patriarchal beliefs, and the need for social identity. Indeed, experiencing violence is a traumatic event that also creates moments of self-blame for not being able to hold family integrity, and the belief that children should grow up with two parents and that marriage is a lifelong commitment, makes it difficult for individuals to seek formal support.Citation6,Citation14 These cultural norms, coupled with social or legal restrictions, make the divorce process complex and costly, hence most women are trapped in violent relationships.

Trauma due to partner violence and other forms of GBV can be detrimental to a person’s dreams, goals, and purpose, hence influencing their expectations of health and wellbeing.Citation8 It has the ability to change and keep someone from showing up their authentic self, utilising their potential to impact on the world positively.Citation15 Furthermore, partner violence affects personal agency since it creates an environment of self-doubt and reduced sense of control over one’s actions and choices in life, especially in societies with predefined gender roles and where victims are blamed for such experiences.Citation6,Citation8,Citation15 The current study aimed to explore the health tensions that Kenyans negotiate in situations of partner violence, especially sexual violence, and how these detriments impact on one’s perception and social construction of health and wellbeing. We adopted a social constructionist lens and the eco-social framework to map the tensions around victimisation or perpetration of violence, personal agency and accountability, sociocultural norms, and the politics around gender equality.

The eco-social framework for IPV and the social construction of health and wellbeing

The current study employed the eco-social framework developed by Nancy KriegerCitation16 to explore the experiences of partner and sexual violence and how these inform the social construction of individual and societal health and wellbeing. By adopting a social constructionist approach, we acknowledge that individual bodies and societies continuously interact with their environments and meaningfully engage in the construction of knowledge.Citation17 People’s perspectives about the meaning of health, disease, and wellbeing are determined by their historical and daily interactions through experiences, observations, and conversations within their context.Citation13,Citation17 For example, a recent study in Kenya showed that experiencing land dispossession due to forced eviction and privatisation significantly affected people’s lives and livelihoods by creating points of stress and distress, hence informing the social construction of health and wellbeing amongst the affected individuals and communities.Citation7,Citation18 Intimate partner violence may also determine how people construct concepts of health and wellbeing, as explored further using the eco-social model in this study.

Founded on post-structuralist perspectives, the eco-social framework allows for a critical analysis of who and what drive overall patterns of health and wellbeing on Kenyans. As demonstrated in studies of marginalised groups,Citation7,Citation19,Citation20 the eco-social model suggests that there are multiple interconnected pathways within and across societies – such as patriarchy, capitalism, social class and other societal arrangements of power and social systems. These social structures determine the extent to which different societal groups have access to functional and basic amenities and resources, including the ability to make autonomous decisions, feel a sense of control, access support services, maintain social capital and connectivity.Citation16 Consequently, systemic structures, such as the prevailing sociocultural norms and practices and the politics of GBV, are critical in people’s experiences of partner and sexual violence. Sociocultural norms, in particular patriarchy, the stigma associated with partner violence, separation, and divorce, and elements of collectivism as it relates to the value of societal expectations, determine how individuals socially construct health and wellbeing. In addition to cultural and structural factors, individuals’ cognitive ability as it relates to personal agency and feelings of being victimised are some important constructs of health surrounding partner and sexual violence. LucknauthCitation21 describes immigrant women as active agents in the social construction of partner violence and in the choices of actions which depend on each woman’s personal agency and traits. In the current study, we explore the social constructs around partner and sexual violence that inform perceptions about health and wellbeing.

The subsequent section of the paper unfolds in three phases. We first discuss the research methodology adopted in our fieldwork in Kenya where we explored the aspects of health and wellbeing that matter to Kenyans. Second, we present the results within four major themes: victims and perpetrators; personal agency; sociocultural influences; and the politics of GBV. In the final section, we discuss the results and give concluding thoughts in relation to key findings, future studies, policy, and intervention advice.

Research methodology

Research design

As part of a broader project that aimed to explore the national wellbeing of LMICs (the Global Index of Wellbeing (GLOWING) project),Citation13 the research presented here investigated how Kenyans socially construct their health and wellbeing in relation to partner and sexual violence. Using an explorative study design, the paper employs a social constructionist and interpretive philosophy which places emphasis on the subjective accounts of participants’ lived experiences,Citation22 researchers’ interpretation of participants’ narratives, and critical analysis of such narratives.Citation23 These research orientations ensure that meaningful results are generated through interviewer-interviewee interactions.Citation24 Situated within the social constructionist epistemological stance, this qualitative research utilises the eco-social analytic framework to explore perceived community health and wellbeing status as it relates to the socio-cultural factors which create challenges, or what we refer to as “the politics of GBV” that middle-aged Kenyans negotiate in dealing with partner and sexual violence. Participants were asked questions about what makes a healthy community and what matters most to individual and community wellbeing.

Study site

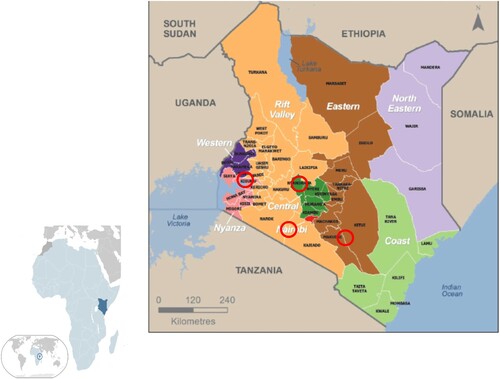

The study was conducted in Kenya, a LMIC (as define by the World Bank as countries with GNI per capita of between $1136 and $4465) located in eastern sub-Saharan Africa (). Kenya has a federal government system and is administratively subdivided into 47 counties. The population is largely young with approximately 34% of women and 32% of men being aged 25–34 years and 29% of both men and women aged 35–49 years.Citation25,Citation26 Even though considered an economic hub for East Africa, the economic growth witnessed at the national level does not trickle down to most Kenyans. As such, a majority of Kenyans (40%) live on less than $1.25 a day.Citation27 Many Kenyans are experiencing social and health inequalities in relation to accessing basic amenities such as water, sanitation facilities, food, and decent housing.Citation28 Additionally, there are regional differences in terms of rural-urban divide, agro-ecological zones, and socio-economic class. About four in 10 urban dwellers (43%) use an improved sanitary facility shared by two or more households, whereas in the rural areas only about 12% have access to similar services.Citation11,Citation28 Gender inequities with reference to employment and engagement in decision-making persist in the country.Citation29 Only 44% of currently married women engage in key decisions such as decisions on their own health care, major household purchases, and visits of their family and relatives within their households. The likelihood of being employed increases with age and differs by gender with 72% of women and 99.9% of men aged 30–34 years having at least some form of cash earnings.Citation28

Figure 1. The map of Kenya showing provincial and county boundaries. Note: Rings on the map show specific counties where the research was conducted

To capture these diversities, the study participants included both men and women of ages 25–49 years recruited from four counties: Kisumu County (in Nyanza Province), Nairobi County (in Nairobi Province), Nyandarua County (in Central Province) and Makueni County (in Eastern Province). Based on socio-economic status (low and slightly higher), urban, arid, and semi-arid areas, the four counties were selected through multistage and purposeful sampling. A combination of purposeful and snowball sampling methods was then used to recruit participants who had lived in the selected counties for not less than five years, and who gave informed consent, for focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interview (IDIs). The presumption was that such individuals held deep experiences of health and wellbeing within their communities, hence allowing for an in-depth exploration of their lived experiences with partner and sexual violence and how these relate to their perceived individual and community health and wellbeing status. The focus of sampling was not on generalisability but rather on sample adequacy to give in-depth information and the sample size was determined by thematic data saturation.Citation23

Research procedure

This study was conducted between January and April of 2017, and it commenced after receiving ethical approval from the University of Waterloo Ethics Review Board (ORE no.: 21946 issued in October 2016) and the Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology Ethics Board (MMU/COR: 403009 [56] issued on 19 December 2016) in Kenya. Local administrative authorities served as community entry points. Area chiefs were asked for permission to conduct the research within their jurisdiction, and they suggested community gatekeepers who were mostly community health volunteers (CHV) to assist with participant recruitment. Identified potential participants were then individually contacted through invitation letters to an information session. Invitation letters were accompanied with an information sheet detailing the research process, the research objectives, expectations, and merits and demerits of participating. A day before the scheduled information sessions, the researcher made phone calls to potential participants to remind them of the meeting and to invite others who might be interested in the study. Information sessions were organised by gender to allow for homogeneity within and heterogeneity between the groups.

Ten homogenous (i.e. single sex) FGDs with middle-aged men and women (n = 99) were conducted in the different counties with each FGD having 5–12 participants to allow for adequate group management.Citation30 The FGDs lasted approximately 90 minutes and were conducted in the language that all participants were comfortable with to allow participants to eloquently articulate their lived experiences of partner and sexual violence and perceived community health and wellbeing. Participants were asked questions about what makes for a healthy community and what matters most to them in relation to having a healthy community, and the role of and their experiences with partner and sexual violence.

In Nyanza region, all the FGDs were conducted in the local dialect (i.e. Luo), whereas in Nairobi (Kibera and Langata), Eastern and Central Provinces both English and Swahili, the two national languages in Kenya were used. In the Nyanza region, an experienced moderator was hired to mentor the researcher in FGD moderation. In this instance, the researcher was a note taker and a co-moderator. All other FGDs were conducted by the researcher with a note taker. To triangulate the FGDs, we conducted IDIs with middle-aged men (n = 7) and women (n = 6). The IDI respondents included populace who were leaders in women’s and men’s groups and had lived in the community for not less than five years prior to the study. All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded with notes taken to capture the main ideas, group dynamics, and non-verbal gestures.

Analysis of data

The audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim and translated from either Luo or Swahili into English by the first author (EO) who is fluent in all the languages. Using QSR NVivo 11.2, the transcripts, field notes, memos, and coding schemes were assembled and organised in readiness for analysis. Thematic analysis using a code-set developed inductively and deductively, allowing for predefined and new themes to emerge, was used to analyse the data.Citation31 To validate the analysis, an independent coder (another researcher, who is a PhD student) performed the analysis and this permitted identification of areas of agreement and disagreement and for consensus on the contentious codes to be reached. The process created opportunities for multiple interpretations and understandings and for broader connections within the data to be generated.Citation32

Researchers’ positionality

The first author in this article (OE) is a woman of Kenyan racial background, born and raised in a rural village in western Kenya, who migrated to Canada in 2015 in pursuit of doctoral training. Her extensive lived and work experience in the Kenyan context may have brought certain biases into the study. She remained cognisant of potential biases she may hold and throughout the study, kept a reflexive journal and an audit trail of all data collection activities. She also asked open-ended questions to allow participants’ voices to be brought to the forefront of the research findings, discussion, and conclusion. The second author (SE) is a white Canadian woman with over a decade of research work experience in LMICs and extensive experience in conducting qualitative research using social theories, including a social constructionist lens.

Results

The study participants were men and women ages 25–49 years recruited from four counties – Kisumu, Nairobi, Nyandarua, and Makueni – to participate in IDIs and FGDs. We conducted 10 FGDs with a total of 99 participants. In Nairobi, participants were drawn from a formal (Langata gated community) and an informal settlement (Kibera). Most of our participants had some level of education, having completed either primary or secondary school. Household size ranged from 1 to 15 members with an estimated monthly income of $0–$900, with the highest income levels recorded in the formal settlements of Nairobi. We also conducted IDIs with 13 lay representatives, policy makers, and representatives of community-based organisations and non-governmental organisations. Most of the IDI respondents had lived in the study counties for over 10 years and were actively working with the community at the time of data collection.

Exploration of participants’ narratives reveals insights into the tensions and the challenges that they negotiate in situations of partner and sexual violence and how their experiences of this violence impact on their perceptions of community health and wellbeing. In this section, we present four premises with regard to social construction of partner and sexual violence and its effects on health and wellbeing among middle-aged Kenyans. First, under victimisation/perpetration of violence, we explore tensions about who is the perpetrator and who is the victim, and whether men and women can be either or both. We argue that men today feel that they are victimised as perpetrators, and yet they are also victims of gender violence. However, because of patriarchy and the prevailing gender inequalities, women remain a disadvantaged segment of population in most societies, especially in LMICs. Women on the other hand feel vulnerable due to the gender power imbalance, an issue that limits their choices and influences their decision-making processes. We discuss this subject in our second sub-theme, agency – “are we (survivors of violence) afraid of being alone?” in which participants, especially women, reflect on their sense of control to take action to quit violent marriage relationships, while also acknowledging the influence of socio-cultural norms on alternative choices. In the third sub-theme we discuss the sociocultural issues including cultural beliefs, social norms, and the inflexible marriage and divorce practices that characterise the social fabric of most African communities. In the fourth sub-theme, the politics of GBV we explore the tension and nuisances that seem to operate at three different levels – individual, community, and policy – that victims of violence deal with to navigate their choices and options. Finally, we conclude that experiencing GBV has direct health and wellbeing effects, and that navigating this form of violence negatively impacts people’s social construction of individual and societal health and wellbeing. The feeling of being victimised and the inability to have control over one’s choices, especially in societies with predefined gender roles and limited political will to support gender equality efforts, negatively affect physical, emotional, and psychological wellbeing. In the subsequent section, we discuss each of the themes.

Victims and perpetrators: men or women or both?

The participants in this research consider partner and sexual violence as constructs that are critical consequences for health and wellbeing of individuals and communities. They acknowledged the tensions that exist in relation to who are the perpetrators and the victims of IPV. Gender equality initiatives may be creating some tensions and as women gain a sense of freedom and become empowered, men feel threatened and want to exert their authority by being brutal and/or violent. In female-only FGDs, participants acknowledged experiencing different types of violence - sexual, physical, social, verbal, emotional, or psychological - which negatively impacted on their health and wellbeing and that of their communities.

Participant 1: A lot of people are being beaten here today.

Participant 3: I am your neighbor, but I will not come to really know what is going on, but I will start to call my neighbors to tell them that she is being beaten just to judge as if your life is perfect.

Participant 2: Here, a lot of women are being hit. I do not know why. I think people are just stressed up; people are trying to make ends meet and men are getting threatened and do not want to be told when they are wrong. You will find that you have just used oil and it’s finished, and someone just hits you seriously as if you have done the worst mistake in your life. (FGD-MF-Langata)

In this conversation, women in the formal settlement in Nairobi describe their lived experiences with partners in a patriarchal society where women often bear the blame for being battered. They acknowledge the role of men in providing for their families and the need for women to prudently use the provisioning, and that women are bound to experience violence if they do not measure up to this responsibility. In times of abuse, there is minimal or no moral or physical support, neighbours gossip and stigmatise the victim, especially in the formal settlements in urban centres. Limited access to resources, especially due to economic hardship, is a contributing factor to family stress and tension in families in low-resource settings. In the rural areas and the urban slums, partner violence is associated with alcoholism, substance abuse, and poverty. In families where access to basic needs such as food and education remains a challenge, men tend to resort to alcoholism as a way of managing stress associated with inability to meeting societal expectations of providing for their families. This leaves women to bear the burden of providing for their families and in the process they are frequently confronted with different forms of violence and abuse, including sexual violence: “ … young girls engage in sex for exchange of commodities. Because of this, they are at risk of and some also acquire HIV, STIs like syphilis. These issues affect even women in this community.” (FGD-MF-P7-Nyanza)

In extreme cases, participants reported the problem of addiction and escalated poverty, as meagre family resources are traded in exchange for alcohol and other abused substances, particularly by men. Even though the female participants in this study talked openly about partner violence, the male participants were hesitant to discuss issues around partner violence, even when they were in abusive relationships. The male participants highlighted some forms of interpersonal violence (e.g. physical attack when they are drunk and helpless, scalding with hot water, gang attacks, chopping off male genitalia) that women have been widely reported in the media as using against them. The male participants associated the lack of reporting to societal expectations of men as being socialised never to complain or cry, traits that are associated with being feminine or of being a lesser man.

“ … for sure, men in this community, some of us are beaten by the women. But we can never say because we’ll be laughed at. People will really ridicule us and say that we are not men enough. So, because of that, most of us die in silence … ” (FGD-MM-P3-Eastern)

Participant 7: There’s a lot on empowerment of the girl child.

Participant 4: The court is protecting them, from the court to the government themselves. All the men in politics are the ones passing these laws.

Interviewer: In essence are you saying that the men are being beaten at home?

Participant 4: Yes, yes, there’re people being beaten, and they are just quiet. Abuse goes both ways …

In underscoring similar sentiments, another participant considered men to have been blamed for a long time in discourses of partner violence.

“ … Men have been demonized for a long time. People are always quick to say that women are being hit and sexually defiled, what about the women who hit the men and the boys that are molested? Men do not talk about it. There are no male activists that are saying that hey, we are being hit out here … there is none, nobody is coming out. But there is Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA), women are always out there.” (FGD-MM-P4-Langata)

Personal agency: “Are we (women) afraid of being alone?”

Equally evident in the narratives are aspects of personal agency – that is, one’s sense of control over their actions as it relates to moral judgement and societal expectations on matters of marital relationships. Analysis of participants’ narratives reveals opposing forces between personal and social desires in situations of partner and sexual violence, with survivors experiencing emotional and psychological stress. Although the female participants acknowledged that domestic violence was prevalent in most households, they also raised questions about their ability to exit such relationships given the societal expectations and individuals’ ability to take action. They asked questions such as: are we afraid of being alone? Or is it that people are concerned about what others and the society say if they are separated or divorced? For example, women in the formal settlement in Nairobi observed:

“ … though the women in Kenya have been empowered by the constitution, there is Federation of Women’s Rights (FIDA), there’s everything but the women themselves cannot come out and say they are affected. Are they afraid of being alone? Or are we afraid and thinking what will my neighbors say, how will they view me, what of my friends? Some people even say I would rather persevere in this relationship so that my people at home should not see me suffering … ” (FGD-MF-P3-Langata)

“ … as a mother, you can’t just let that happen, the child must eat, the child has to go to school. Now, you have this man who is becoming a child and supposedly your husband. … Women here in Kenya or here in this place we have a problem with our men. I do not know whether men today are raised right … There is that mentality that our parents raised the men to know that the women will take care of them. Or they raised us as girls to know that we have to take care of the men. In this community today, there is a problem. Some men stay home and do not look for any employment opportunities while the lady goes to work. This contributes to violence. The men need to take care of us and then us we take care of the community; but when you are not taking care of me and hit me, I’ll be depressed, mentally I will even go insane, I can’t be healthy, I can’t have a good life.” (FGD-MF-P3-Langata)

In demonstrating the intergenerational effects of partner violence, participants highlighted how the vice affects the health of the community and, more specifically, that of the children who are denied their full potentials and capabilities in life. Additionally, children that frequently witnessed violence between their parents may develop fear and trauma, resulting in parent–child conflict especially in teenage.

“ … if the kid of 5 and 7 years sees me battering my wife or their mother, there is something they will develop in their mind. They will have fear and hatred. You see! … when the child gets to the age of 16 years, still they have those memories in them. That can be a source of father-daughter or father-son conflict in teenage.” (FGD-MM-P1-Nyanza)

Sociocultural influence on experiences of partner and sexual violence

Culturally, men are socialised as family heads. As argued by CarterCitation33 religious doctrines mandated by male authorities have historically contributed to attitudes and systems that promote male dominance. Such doctrines come from religious leaders who depict women as inherently inferior or subservient to men. Among such patriarchal systems, violence in society has become normalised.Citation2 The findings in this paper highlight that men have abdicated their socially sanctioned responsibility of seeking guidance from the supernatural being (God) as the head of the household, making it difficult for the women to be submissive and just follow them. Hence, when women fail to meet the male definition of submission, they are battered by the men who assume that masculinity and strength demonstrate their ability to take up their “godly-assigned” responsibility.

“ … to me what I can say is that many people do not see it as a spiritual thing. You see in the bible God says that the man should be the priest of his house, the man should love his wife and the wife should be submissive. So, you will find that the man … does not look to God for guidance. … their guidance is from someone else may be your friend. You see when that happens it will be difficult for your wife to be submissive to you when you have lost direction.” (FGD-MM-P3-Langata)

“ … you get that the man doesn’t work, and the woman is the breadwinner in the family. So, the man feels intimidated … So, the man feels inferior, and it ends up in him being depressed and you find that there’s a lot of suicide occurrences in this area. It doesn’t go for more than a month without getting anybody from either the river or from the forest that have committed suicide. That is the major cause – family conflict. Also, the rate other vices like rape, incest are also quite frequent. The community is no longer healthy.” (IDI-MF-Ndaragua)

“ … The moment you know you are getting violent, somebody has slapped you once and you keep on protecting him, you see, already this guy has reduced your self-esteem … the women in Kenya have been empowered by the constitution, … but the women themselves they cannot come out clearly and say that I am affected as a woman. They are afraid thinking of how their neighbors and other family members will view them. I would rather persevere in this relationship so that my people at home should not see me suffering … like even now if I say that I am single, somebody will say that you see she is single do not walk with her, she is a prostitute, she is wrong numbered woman. … You see she doesn’t have a husband. So, most women will say that let me stay in the house even if I am being violated sexually or physically.” (FGD-MF-P4-Langata)

“Look at a lady who is 28 years and she has succeeded, and you are driving and doing your stuff what would they say, they would say you are a prostitute. But look at a man who is of the same age 28 years who is driving and doing his stuff they would say that he is working hard. … You know that you are not a prostitute, and you have your own land, you have your car but the people in this society will say that she is wrong number, she is a prostitute … ” (FGD-MF-P1-Langata)

The politics of GBV, opportunities, and challenges

In spite of the progress that Kenya has made towards women’s empowerment,Citation29,Citation33 real gender equality in other aspects of daily living, including the socio-cultural perspectives (i.e. people’s behaviours and mental processes as shaped by the prevailing social and cultural systems), remains far from a reality. The sociocultural systems in societies create three distinct points of tension that Kenyans negotiate in their daily life. We refer to these tensions as the politics of GBV which manifest at individual, community, and national levels. However, we acknowledge that the tensions are indistinct as they interrelate and depend on each other.

At the individual level, the victims of partner and sexual violence are frequently confronted with dilemmas as to whether their individual needs and preferences should come before societal expectations or vice versa. The most affected are women, who tend to have less power in making independent choices. For example, among the concerns women have to deal with when they find themselves in abusive marriage relationships is whether to take legal action against their spouse, who in most cases is the main family breadwinner. Women observe that in situations where a woman goes ahead to formally report a case of violence, such an action is used against the woman and in extreme situations, she is forced to separate and the man encouraged to marry another wife.

“ … among the Luos [a tribe in Kenya], if a woman is sexually defiled or abused by the husband, if she reports the husband and the husband is taken to court or jail, then that can be an opportunity for the community to make the man and the woman to part ways because the community believes that the man is the head of the family and is always right … ” (FGD-MF-P7-Kibera)

At the policy level, there are challenges that gender equality champions experience. In societies that are male-dominated and characterised by populist politicians who view society as a fundamental moral struggle between groups of people, decisions on policies that are passed or revoked are significantly dependent on the gender implications of such policies. Male politicians often do not support policies that they view as beneficial to women, especially if they are thought to disadvantage the males in society. A case in point is when the male politicians in Kenya legalised polygamous relationships. From this research, a female policymaker narrated experiences in fighting for gender equality policies:

“ … when you start that issue of GBV even in the assembly, the men will shut you down and tell you the way the men are suffering outside here, and you are coming here to talk about women. They believe that women can talk … but for men, they are not talking … ” (IDI-Policy-maker-Nyanza)

“ … in media, they talk of men do this, women do this, and people call in and they complain and complain you know! Never once have they brought in a psychiatrist or those guys who can help you like a counsellor. I feel like you are always giving us the problem, but you never try to create a discussion around the solution. So that should be something that should be taken into consideration if you have a show like that one … ” (FGD-MM-P4-Langata)

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the social construction of health and wellbeing around the experiences of partner and sexual violence. Analysis of participants’ narratives reveals the tensions and the nuisances that the survivors of violence deal with as they navigate their daily lives. In the context of violence, women might want to leave their current violent relationship, but they are limited by prevailing socioeconomic factors. Economic dependence, and community or societal norms, often embedded in patriarchal societies, and the view of marriage as being permanent, are important limiting factors in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation29,Citation34 The tensions that victims of partner and sexual violence are confronted with not only relate to their individual interests but also their social identity and being considered socially fit within their communities.Citation1 The society expects women to be submissive and to hold their families together despite the experiences of violence. In cases of divorce or separation, the woman is often blamed and viewed as the cause of the problem. Therefore, women are socialised into tolerating occurrences of violence as the norm and as a sign of a “strong woman”, often remaining silent and, in doing so, keeping the secrets of their households.Citation6,Citation14

Additionally, women are confronted with the social stigma of being separated or divorced as this is often linked to promiscuity, and to what participants referred to as a social misfit or a “wrong numbered woman”. In such instances, the effects of being socially isolated are so enormous for their mental and emotional wellbeing that women opt to stay in unhealthy relationships at the expense of their personal wellbeing. As revealed by Wood and colleagues,Citation1 women are not able to leave violent relationships and most women choose to engage in informal support services, change behaviours perceived to cause conflict with the partner, and endure different forms of violence – all in support of their family and in the desire to conform to social and cultural norms. The men on the other hand are confronted with the desire to reaffirm their masculine position and the societal expectations of being providers to their families. With changing gender roles and increased knowledge about gender equality, men feel threatened and assert themselves through violence and, in certain cases, their reactions have been met with retaliatory attacks.

Cultural norms and practices play a critical role in propagating gender imbalances and have the potential to create violent societies characterised by frequent GBV.Citation1,Citation6 For example, increased cases of sexual violence, suicide, and homicide are reported regularly and influence how Kenyans perceive and define the health and wellbeing of their communities. As the society changes socially and economically, and with the gender equality efforts which seek to empower women and build their personal agency and decision-making capacity, there seems to be a sense of disempowerment among men, not only in the rural areas but also in the cities.Citation29 This partly explains the rising rate of partner and sexual violence in Kenya as men seek to assert their socially and culturally constructed leadership responsibility. Moreover, high unemployment rates and inflation which limit the ability to meet basic needs, and the availability of relatively affordable liquor, are other important explanatory factors in the rising cases of violence in Kenya.Citation6,Citation29 Global emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, global inflation, social and economic instability, and climate change are creating increasingly violent environments of violence not only at global and societal levels but also at the household level. According to UN Women,Citation35 the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the precarious sociocultural and economic situation as private spaces of home became unsafe areas for most women and children following the pandemic control measures.

Although women and children disproportionately bear the burden of partner and sexual violence, men also feel that they have been victimised for a long time and are seen as perpetrators of violence whereas in reality, they are also experiencing some GBV in the form of retaliatory attacks. In societies where men are socialised as people who should never show signs of defeat and of discomfort, the majority of men are suffering in silence. As demonstrated in recent literature on GBV, men and boys could also be victims from mutual aggression or perpetration by women.Citation6,Citation36 Likewise, the findings in this research affirmed that men are not just perpetrators, but they are also victims of violence as it has been witnessed in Kenya in the recent past with retaliatory attacks by women on men. The recent KNBSCitation27 reported that both men and women experience some form of violence but women (57%) are more likely to report partner violence than men (11%). Additional ethnographic research may suffice to unearth the systemic and immediate factors contributing to the emerging trends of partner and sexual violence, suicides, and homicides which not only impact on the current population but also have the potential to cause intergenerational trauma.

Trauma associated with experiencing or witnessing IPV can cause emotional and physical reactions that can have long-term health effects such as increased possibility of obesity, diabetes, cancer, heart attack, and stroke especially later in life.Citation15 Recent studies reveal that partner and sexual violence negatively impact several interdependent dimensions of health including – the physical, mental, social, financial, spiritual, environmental, and vocational wellbeing.Citation1,Citation8,Citation15 Trauma due to partner and sexual violence and other forms of GBV can be detrimental to a person’s dreams, goals, and purpose, hence influence their view of health and wellbeing. GBV can change people and keep them from “showing up their authentic self”, or utilising their potential to impact on the world positively. As demonstrated in the current study, violence creates an environment of self-doubt and reduced sense of control over one’s actions and choices in life, especially in societies with predefined gender roles and where victims are blamed for such experiences.Citation8,Citation21 Such experiences not only affect women’s social construction of health and wellbeing but also men’s, as they strive to reaffirm their position and masculinity in such contexts. As Kenya makes technological advances and nearly all Kenyans now have some form of access to social media and other media channels, there is need for studies to evaluate the best approaches and programmes that could be incorporated through these channels to create forum for discussions on this sensitive topic. Such programmes must endeavour to create welcoming spaces for all Kenyans and suitable platforms for candid discussions on gender inequalities, experiences of partner violence, political goodwill and policy interventions to address socioeconomic inequalities and other systemic biases.

This study is not without limitations and weaknesses. This is a qualitative study that traversed several regions of Kenya, but we acknowledge that given the study methodologies, our results are not generalisable to the entire Kenyan population. However, diverse perspectives with regard to the social construction of community health and wellbeing in relation to partner and sexual violence are represented. Although there are several shared experiences on the research topic, it is beyond the capacity of this study to collect trend and frequency data on the themes and the social constructs identified. Additionally, this study relied on self-reported data which may be prone to social bias, especially with respect to discussions on sensitive topics such as partner and sexual violence and the social construction of health. Therefore, interpretation of the study findings must be done with these limitations in mind. However, our findings are comparable to other studies that have adopted similar methodologies.

Conclusion

This study draws three main conclusions and contributes to the conversation around partner and sexual violence and its impacts on the social construction of health and wellbeing. First, GBV and particularly partner and sexual violence, are key constructs for both men and women in their definition of health and wellbeing and that of their communities. Experiences of violence create tensions between men and women in most communities and in patriarchal societies, where numerous challenges confront the victims of violence as they negotiate whether to prioritise their individual preference or to act in a manner that is socially and culturally acceptable. Given the prevailing sociocultural systems, women tend to be more disadvantaged and bear the heaviest burden of violence in most societies.

Second, women experience social stigma associated with domestic violence and when separated or divorced in situations of unsafe relationships, they are viewed as social misfits. As such, most women opt to stay in unhealthy relationships to avoid social isolation. Inversely, men are always framed as perpetrators of violence. However, the findings here show that they may also be victims of mutual aggression by women as recently witnessed where women have retaliated through gang attacks, chopping of male genitalia, and use of hot water. These traumatic experiences are detrimental to people’s dreams, goals, and purpose, hence influence their view of individual and societal health and wellbeing and inhibit their development and potential for positive action.

To address the health and wellbeing challenges associated with IPV requires interventions that go beyond the immediate service provision, such as making healthcare and psychosocial support accessible, to also address structural biases such as socioeconomic and gender inequalities through policy interventions.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation and methodology, OE and ES; data collection and analysis, OE; writing original draft preparation, OE; reviewing and editing, ES and EO; project administration, supervision, and funding acquisition, ES. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Carise Thompson, who helped with the coding and inter-coder reliability test.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wood SN, Glass N, Decker MR. An integrative review of safety strategies for women experiencing intimate partner violence in low-and middle-income countries. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021;22(1):68–82. doi:10.1177/1524838018823270

- Cadilhac DA, Sheppard L, Cumming TB, et al. The health and economic benefits of reducing intimate partner violence: an Australian example. BMC Pub Health. 2015;15(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1931-y

- Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, et al. Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet London Eng. 2015;385(9977):1555–1566. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7

- Samarasekera U, Horton R. Prevention of violence against women and girls: a new chapter. Lancet London Eng. 2015;385(9977):1480–1482. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61775-X

- Mahenge B, Likindikoki S, Stöckl H, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and associated mental health symptoms among pregnant women in Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;120(8):940–947. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12185

- Gillum TL, Doucette M, Mwanza M, et al. Exploring Kenyan women’s perceptions of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(13):2130–2154. doi:10.1177/0886260515622842

- Onyango EO, Elliott SJ. Traversing the geographies of displacement, livelihoods, and embodied health and wellbeing of senior women in Kenya. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2022.

- Paulson JL. Intimate partner violence and perinatal post-traumatic stress and depression symptoms: a systematic review of findings in longitudinal studies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;23(3):733–747. doi:10.1177/1524838020976098

- Hatcher AM, Romito P, Odero M, et al. Social context and drivers of intimate partner violence in rural Kenya: implications for the health of pregnant women. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(4):404–419. doi:10.1080/13691058.2012.760205

- Odero M, Hatcher AM, Bryant C, et al. Responses to and resources for intimate partner violence: qualitative findings from women, men, and service providers in rural Kenya. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(5):783–805. doi:10.1177/0886260513505706

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, & ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic Health Survey 2013-14. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2015.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, & ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic Health Survey 2022. Rockville, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2022.

- Onyango EO. Exploring health and wellbeing in a low-to-middle income country: a case study of Kenya. (PhD, Degree). Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: University of Waterloo; 2019.

- Okeke-Ihejirika P, Yohani S, Salami B, et al. Canada’s Sub-Saharan African migrants: a scoping review. Int J Intercult Relat. 2020;79:191–210. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.10.001

- Scrafford KE, Grein K, Miller-Graff LE. Effects of intimate partner violence, mental health, and relational resilience on perinatal health. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(4):506–515. doi:10.1002/jts.22414

- Krieger N. Epidemiology and the people’s health. New York City, USA: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Gatrell AC, Elliott SJ. Geographies of health: an introduction. Third ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015.

- Onyango E. Managing livelihood in displacement: the politics of land ownership and embodied health and well-being. In: J Eastin, K Dupuy, editors. Gender, climate change and livelihoods: vulnerabilities and adaptations. Oxfordshire, UK: CAB International; 2021. p. 56–68.

- Crocker SA. Diabetes and the off-reserve aboriginal population in Canada. (Master of Science in social dimensions of health programs). Britisch Columbia: University of Victoria; 2013.

- Richmond CA, Ross NA. The determinants of First Nation and Inuit health: a critical population health approach. Health Place. 2009;15(2):403–411. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.07.004

- Lucknauth C. Racialized immigrant women responding to intimate partner abuse (Doctoral dissertation). Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; 2014.

- Corbin J, Strauss A, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research. San Jose, USA: San Jose State University; 2014.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: Pine Forge Press; 2006.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research: theories and issues. In: SN Hesse-Biber, P Leavy, editors. Approaches to qualitative research: a reader on theory and practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. p. 105–117.

- KNBS. 2019 Kenya population and housing census volume III: distributuioon of population by age and sex. Nirobi, Kenya: KNBS; 2020a.

- Muthembwa K. World Bank: working for a world free of poverty: an overview of Kenya; 2016. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/overview.

- KNBS. Survey on socio economic impact of COVID-19 on households report, wave two. Nairobi. Retrieved from Nairobi, Kenya; 2020b.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. The Kenya Economic Survey – 2020. (1). Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2020.

- Ringwald B, Tolhurst R, Taegtmeyer M, … Giorgi E. Intra-urban variation of intimate partner violence against women and men in Kenya: evidence from the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(5-6):5111–5138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221120893.

- Shurmer-Smith P. Doing cultural geography. London: Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 2002.

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Washington, DC: SAGE; 2014.

- Hay I. Qualitative research methods in human geography. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Carter J. Patriarchy and violence against women and girls. The Lancet. 2015;385(9978):e40–e41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62217-0

- Muigua K. Attaining gender equity for inclusive development in Kenya. doi:kmco.co.ke; 2015.

- Sommer M, Likindikoki S, Kaaya S. Boys’ and young men’s perspectives on violence in Northern Tanzania. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(6):695–709. doi:10.1080/13691058.2013.779031

- UN Women. Gender equality matters in COVID-19 Response; 2022. Available from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response.

- Davies SE, True J. Reframing conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence: bringing gender analysis back in. Secur Dialogue. 2015;46(6):495–512. doi:10.1177/0967010615601389