ABSTRACT

A large body of literature discusses the relationship between growth aspirations of small and medium-sized enterprise owners in emerging economies and the social capital and formal education of the entrepreneur. We argue that inherited cultural capital, rooted in the social background of the owner, is an additional important element to explain differences in growth aspirations, in particular for business owners at the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) in less developed countries. Our data confirm that different elements of inherited cultural capital do have a major influence on aspirations. The results suggest that this is related to the observation that small businesses operating at the BoP, in a weak institutional context, face difficulties in accessing social capital.

Introduction

A decade ago, Bruton (Citation2010) observed a lack of attention among management scholars for businesses at the Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP; Karnani, Citation2007; Prahalad & Hammond, Citation2002). This call appears to have some impact, as in recent years the attention of management scholars for these businesses has increased (Acquaah, Citation2012; Bulte et al., Citation2017; Dutt et al., Citation2016; George et al., Citation2016; Lent, Citation2020; Qureshi et al., Citation2016; Sutter et al., Citation2013). In much of this literature, it is acknowledged that entrepreneurship can be seen as one of the instruments that contributes to the solution of poverty (Bruton et al., Citation2013; Goel & Karri, Citation2020; Liguori & Bendickson, Citation2020). McMullen (Citation2011) even proposed a “theory of development entrepreneurship” (p. 187). In line with this literature, we analyze the growth aspiration of small business owners active in a traditional retail sector at the BoP.

Extant literature shows that many firms in emerging countries are seriously resource constrained and that social capital (for example, professional networks) and institutionalized capital (for example, formal education), are important assets influencing the access to resources and, subsequently, the growth aspirations of firm owners (Efendic et al., Citation2015; Manolova et al., Citation2007; Puente et al., Citation2017). Participation in professional networks is expected to provide better access to relevant resources (Adler & Kwon, Citation2002; Batjargal, Citation2003). Moreover, the social capital created by organized actors may be helpful to replace or repair institutional weaknesses (Acquaah, Citation2012; Sutter et al., Citation2013).

In line with this latter argument, Battilana et al. (Citation2009) noted an important nuance and argued that what they call “institutional entrepreneurship” (p. 65) is costly and that powerless actors are less able to challenge institutional weaknesses. Put differently, firms at the BoP are seriously resource constrained and, therefore, lack the resources, or power, to create the social capital needed to access crucial resources efficiently. In fact, we observe that, among the business owners in our sample, only a few are members of a professional business association. This suggests that for these resource-constrained businesses social capital is not an effective asset to create access to needed resources. Instead, other factors, which are currently overlooked, may be of importance for our understanding of growth aspirations in a BoP context. The contribution of this article to extant literature is to improve our understanding of inherited cultural capital for small firms at the BoP. We suggest that inherited capital replaces “costly” social capital as an important asset to address institutional challenges.

If small firms at the BoP lack the needed resources to invest in social capital, they have to deploy other instruments to address the challenges that result from the imperfect markets in which they operate (North, Citation1991). We argue that these small businesses have to rely more on their inherited cultural capital. The concept “cultural capital” was coined by Bourdieu (Citation1986, p. 243) and comprises the knowledge components that are intentionally acquired and components that are passively inherited via social background, especially during socialization processes. Conceptually, we differentiate between two components of cultural capital in addition to social capital: (a) inherited cultural capital and (b) institutionalized cultural capital.

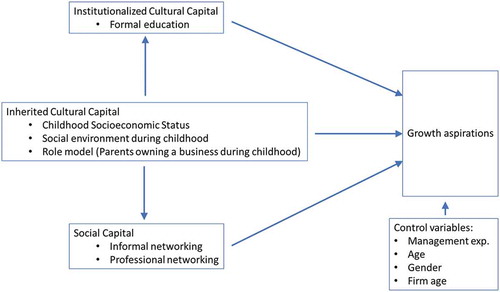

For this study we define inherited cultural capital as the disposition, developed during childhood, to appreciate and understand entrepreneurial action—for example, the existence of role models in the family and the education of parents that may help to develop entrepreneurial capabilities (cf. Erikson & Goldthorpe, Citation2002). Next, we define institutionalized cultural capital as actively accumulated knowledge, mainly obtained through formal education. Finally, social capital refers to the networks and relationships among individuals; in our study, specifically membership in professional network organizations. We note that there is a crucial difference between social capital and inherited cultural capital. Access to resources that result from social capital depends more on the action taken by the owner today, while access to resources related to the inherited cultural capital is rooted in the past in which the owner was raised.

Remarkably, the role of inherited cultural capital has received little attention in the literature (Thornton et al., Citation2011). Missing this element in the analysis leads to an underestimation of the hurdles small businesses face and, also, the institutional support they need in order to make entrepreneurship a successful instrument in the struggle against poverty. The major contribution of this article is to fill this gap by focusing the analysis on the influence of the inherited cultural capital on growth aspirations, in particular for small business owners operating at the BoP in a weak institutional environment (Bourdieu, Citation1986; McMullen, Citation2011), thereby adding to the debate on growth aspirations of firm owners in emerging economies (Efendic et al., Citation2015; Manolova et al., Citation2007; Puente et al., Citation2017).

We document that differences in growth aspirations among small business owners active at the BoP are related to the inherited cultural capital to which they have had access. In particular, the education obtained by the parents and the existence of a role model (parents owning a business) during childhood appear to influence the growth aspirations of their children once they become business owners. Membership in professional network organizations (social capital) is uncommon in the environment under study. We conclude that to date the potential role of professional networks in the entrepreneurial process at the BoP is still underexploited. We take this as a challenge for policy makers. The establishment of network organizations, targeting specifically entrepreneurs at the BoP, should be encouraged so that the business owners get access to the potential benefits.

In the next section, we present a theoretical framework and formulate hypotheses. Subsequently, we present the data collection and research methods, followed by the presentation of the results. Finally, we discuss the implications.

Theoretical background

Doing business in a weak institutional environment at the BoP

Management scholars nowadays pay substantial attention to small businesses at the BoP. Prahalad and Hammond (Citation2002) coined the concept of BoP and observed the potential of markets serving the billions of people at the bottom of the economic pyramid. Although the view is also criticized (Karnani, Citation2007), the BoP concept has been adopted in the discussion of entrepreneurship as an instrument to reduce poverty in developing countries.

Entrepreneurial activity is related to the institutional environment (Batjargal, Citation2003; Goel & Karri, Citation2020). A strong institutional system and institutional trust are supportive of business growth (Welter & Smallbone, Citation2006) and growth aspirations (Estrin et al., Citation2013). A weak institutional environment may result from institutional voids or weak enforcement of formal institutions. Following Meyer et al. (Citation2009), we define an institutional environment as weak when it does not “ensure effective markets or even undermines markets” (p. 63). Tanzania is ranked number 132 among 190 countries on the list of “Ease of Doing Business in 2017” (World Bank, Citation2017). In such a context we do have reason to expect that the transactions of entrepreneurs active at the BoP are coordinated in a weak institutional environment.

In the literature, two instruments are discussed that may repair some of the weaknesses of the institutional environment: family business and social capital. Several papers discuss the important role of family ties in the process of opportunity recognition and getting access to resources (Arregle et al., Citation2015; Khayesi et al., Citation2014). Put differently, in a weak institutional environment, personal exchange (North, Citation1991) may still be a leading governance instrument. In a similar vein, social capital may facilitate exchange and substitute for weak institutions (Acquaah, Citation2012; McMullen, Citation2011; Sutter et al., Citation2013; Uzo & Mair, Citation2014). Although this literature generally highlights that in a weak institutional environment the effects of social capital are likely to be more pronounced, insights from Battilana et al. (Citation2009) noted an important nuance by suggesting that the creation of social capital comes at a cost of organizing peers. Availability of resources, power, and reputation are necessary ingredients to make this instrument work. In particular, for businesses operating at the BoP it is not evident that these requirements are fulfilled.

Growth aspirations

A large body of literature in the field of entrepreneurship and small business addresses business growth and the role of aspirations. While some ventures have pronounced growth aspirations and are also able to realize high growth rates, most firms are born small and stay small (Shane, Citation2009). Economic theories generally assume that owner-managers of small businesses have economic aspirations, mostly those of profit maximization (Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2003). In reaction to this, Davidsson (Citation1991) argued that variables of a more psychological nature have to be taken into account if growth aspirations are to be understood. He claims that perceptions of ability, need, and opportunity explain about one third of the variance in growth motivation, which in turn is associated with actual business growth (Delmar & Wiklund, Citation2008; Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2003). In his quest for other factors that influence growth aspirations, Kolvereid (Citation1992) revealed that growth aspirations are related to start-up motives, education, industry, and organizational variables. Wiklund et al. (Citation2003) found that noneconomic factors were more important than expected financial outcome in determining owner-managers’ growth aspirations.

In another related study, Manolova et al. (Citation2007) examined the effect of human capital and social capital on growth aspirations. They concluded that experience and outside advice through networking were influencing owner-managers’ expectancies. Efendic et al. (Citation2015) showed the importance of social capital if growth aspirations in postconflict zones are analyzed. Puente et al. (Citation2017) considered a large number of contextual, individual, and business factors to analyze growth aspirations of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Venezuela. Contributing to this discussion, we argue that inherited cultural capital is of central importance when studying small firms at the BoP in a weak institutional environment.

In order to address this gap, this study adopts Bourdieu’s social theory (Citation1986), which focuses on the influence of socialization processes in developing an individual’s aspirations. According to this theory, aspirations are determined by the available sources of cultural, social, and financial capital.

Cultural capital and growth aspirations at the BoP

Bourdieu (Citation1986) defined cultural capital as forms of knowledge, skills, education, and advantages that give a person a higher status in society. He makes a distinction between embodied, or inherited, cultural capital and institutionalized cultural capital. In this article, inherited cultural capital is defined as the disposition, developed during childhood, to appreciate and understand “entrepreneurial” action. Institutionalized cultural capital concerns accumulated knowledge mainly obtained through formal education.

We already noted that social background in most network analyses and entrepreneurship literature is paid scant attention (Hout & Rosen, Citation2000; Thornton et al., Citation2011). Although reference is made to the importance of role models in entrepreneurship literature (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003), empirical research on role models for (nascent) entrepreneurship is scarce (Bosma et al., Citation2012). This may be understood for developed economies operating in a strong institutional setting where weak ties are indeed needed to identify opportunities resulting from new technologies (Engel et al., Citation2017). However, the Tanzanian BoP context is better characterized by a weak institutional environment and low tech. In line with Bourdieu, we argue that in such a situation a conducive social background during childhood is important to develop the required talent to appreciate and understand entrepreneurial opportunities and, subsequently, higher growth aspirations. From Bourdieu’s theory (Citation1986) we extract the following variables to reflect the inherited cultural capital to which owners have had access: childhood socioeconomic status (SES), the social environment, and the existence of entrepreneurial role models. We propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Inherited cultural capital (childhood SES, social environment during childhood, parents’ role model) has a direct positive effect on growth aspirations of small business owners operating at the BoP.

We take formal education as a proxy for the institutionalized cultural capital to which the owner has had access. A large body of literature shows that formal education influences growth aspirations and facilitates the assessment of perceived opportunities (Davidsson, Citation1991; Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003; Manolova et al., Citation2007). From Gimeno et al. (Citation1997) we derive a related argument. They discussed a higher threshold for entry in the business world for the higher educated. In line with this argument, higher education implies that the choice for entrepreneurship will have a higher opportunity cost. Consequently, those among the higher educated who start a business will have higher growth aspirations. From this literature, we derive the following hypothesis:

H2: Institutionalized cultural capital has a direct positive effect on growth aspirations of small business owners operating at the BoP.

Children who have been exposed to a more conducive social background from birth in their middle- and upper-class families feel more comfortable in schools, communicate easily with teachers, and are therefore more likely to perform well (De Graaf et al., Citation2000). Put differently, the inherited cultural capital influences access to formal education. The influences of significant persons, reference groups, social status, and ethnic group cultures are key components having a critical impact on the development of individuals and their conceptions of their possible futures (Jacobs et al., Citation1991). Therefore, we expect that formal education mediates part of the inherited cultural capital effect on growth aspirations:

H3: Institutionalized cultural capital mediates part of the effect of inherited cultural capital on growth aspirations of small business owners operating at the BoP.

Social capital and growth aspirations at the BoP

Individuals access network resources, or social capital, because of group membership. Bourdieu (Citation1986) defined social capital as “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition” (p. 249). This definition is quite similar to the one proposed by Adler and Kwon (Citation2002): “Social capital is the goodwill available to individuals or groups. Its source lies in the structure and content of the actor’s social relations. Its effects flow from the information, influence, and solidarity it makes available to the actor” (p. 23).

In network analysis, social capital is generally defined in a broad way, covering weak and strong ties, or bonding and bridging ties. Their effectiveness depends on the task contingencies (Adler & Kwon Citation2002). Strong and bonding ties are expected to be more important in emerging markets where trust is key, while weak and bridging ties are more effective in high-tech developed markets where access to new information is crucial (Stam et al., Citation2014). In the context of our study, we utilize membership in networks is a proxy for social capital—which is a key variable in our model.

It may be argued that strong ties cover family and friends and strongly overlap with the social background as defined by Bourdieu. For example, Davidsson and Honig (Citation2003) identified parents’ business ownership as one of the aspects of social capital. In their survey design it remains unclear whether parents’ business ownership played a role in the past or whether it plays a role in the present business network. Among the business owners we interviewed we observed that many parents were not actively involved in the businesses due to their age/retirement, or were active in a different industry. In most cases, the parents appear to have played a role in the past, for example, through the formation of aspirations, education, and access to start-up capital. Therefore, we prefer to take this variable as part of the embodied cultural capital, as for most small business owners the effect is not derived from participation of the parents in the business at this point in time.

In the field of entrepreneurship, social capital is recognized as a resource that enables and constrains behavior (Engel et al., Citation2017). Similarly, it has been found that benefits received through networking are positively related to performance of nascent entrepreneurs (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003), small firm performance (Stam et al., Citation2014), and growth expectancies (Manolova et al., Citation2007). We follow Manolova et al. (Citation2007) in their interpretation of social capital and focus on membership in professional networks. The advantage of this approach is that this variable is relatively easy to observe. Information about the network ties, network density, and type of resources provided is difficult to obtain and goes beyond the scope of this study. We add informal networks (for example, tribalist, gender, religion, politics), as these may play an important role in Tanzania (Acquaah, Citation2012). Accordingly, we test the following hypothesis:

H4: Social capital has a direct positive effect on growth aspirations of small business owners operating at the BoP.

In line with the argument presented above, regarding the role of formal education (H3), we also expect that access to social capital may depend on the inherited cultural capital. Like educated parents who facilitate the performance of their children at school, role models may facilitate their children’s access to social capital. This is in line with the argument presented by Light and Dana (Citation2013) who suggested that social capital promotes entrepreneurship, but only if supportive cultural capital is in place. Therefore, we hypothesize that social capital may mediate (substitute for) the effect of the inherited cultural capital.

H5: Social capital mediates part of the effect of inherited cultural capital on growth aspirations of small business owners operating at the BoP.

We synthesize the discussion in our conceptual framework (), showing that growth aspirations of business owners operating at the BoP in a weak institutional environment are rooted in the social background: inherited cultural capital. Growth aspirations also depend on institutionalized cultural capital (formal education) and social capital (networking), which are both depending on inherited cultural capital.

Data and method

Data collection approach

This study was executed in two phases. We started with an exploratory case study (10 cases) to identify the relevant survey questions and to determine the feasibility. We recall that the institutional environment in Tanzania is weak and that in such an environment cooperation of respondents may be a challenge as people are expected to hesitate to talk about their business with outsiders (World Bank, Citation2017). The case study confirmed that it is difficult to obtain unbiased figures about turnover, profits, and income in a survey. At the same time, we observed that the owners were interested in talking about their business.

The surveys were conducted by one of the authors speaking the local language. The survey was translated into Swahili by the researcher and, to ensure the correct translation, a language expert did the same. A consensus was found for the differences between the two versions. Finally, after a pretest, only a few questions were modified.

Because of the large number of respondents to be covered in a wide geographical area and the need to collect data within a short period of time, four enumerators assisted one of the authors with the data collection. The assistants were trained on the objective of the research and the content of the questionnaire. After handing in the results the responses were checked for errors, omissions, and inconsistencies by one of the authors.

The data used in this article were collected from four urban regions in different parts of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam (102 observations), Morogoro (62 observations), Dodoma (46 observations), and Mwanza (100 observations). Dar es Salaam is the largest city in the east of the country. Mwanza is the largest town in the north, while Dodoma is the capital, located in the center of Tanzania. Morogoro is a smaller urban town in the southwest. We chose urban over rural areas because urban centers are commercial centers where many SMEs are located. We selected retailing serving the BoP as it employs many small business owners who are easily contacted in the commercial centers of the towns. The large majority of the retail businesses in the survey were convenience stores and also some owners of stationary stores and catering services were interviewed. Among these firms, the willingness to participate in the survey was very high. Only a few, about 1 percent of the contacted businesses, refused to cooperate.

Due to a lack of a proper database of small business owners in Tanzania, the selection of owner-managers could not be done by probability sampling methods. When the research team visited one of the town councils we found that the list of business owners was not computerized and that in quite a number of cases addresses were lacking. Moreover, informal businesses were not included in the formal registrations. Therefore, we used purposeful quota sampling reflecting the size of the towns. The research team visited the commercial centers in the towns and owner-managers were reached in their business locations. Only those who were at least five years in business were requested to participate in the study. This study was mainly interested in established firms. We decided to leave start-ups out of the sample in order to make sure that respondents had some experience and were able to survive in their competitive environment.

Previous research has recommended that the sample size should have a ratio of five to 10 observations for each independent variable (Hair et al., Citation2006). The current study consists of less than 20 independent variables; using this criterion we needed about 200 cases. In order to remain on the safe side we planned to interview 300 owner-managers and finally we were able to realize 310 complete interviews with the available resources.

The use of nonprobability sampling methods for studying small and micro enterprises is quite common in Tanzania (International Labour Organization, Citation2003). However, we acknowledge that this method may produce a sample that is not representative. In order to account for this we compared some sample characteristics with the results presented in other reports. In total, 42 percent of the respondents in our sample are female business owners. This average is quite in line with the numbers observed in the Business Survey (United Republic of Tanzania [URT], Citation2007b) and the Integrated Labour Force Survey (URT, Citation2006) indicating that 37.7 percent and 43.6 percent of the self-employed in their populations were female. Regarding age, we observe that the majority of business owners are not older than 40 years (72 percent of the respondents). This figure is in line with the Integrated Labour Force Survey (URT, Citation2006) reporting that 67 percent of small business owners are younger than 40 years and the International Labour Organization (Citation2003) observing that most small business owners were aged between 31 and 40 years. The large majority of respondents were married (69 percent), which is quite in line with the results presented in the Household Budget Survey (URT, Citation2007a). Finally, we checked for the education level. In our sample, 41 percent of the business owners had only a primary education. Other studies in Tanzania report 67 percent (URT, Citation2006). We note that the difference in these numbers may be related to the sampling area: urban environments where access to education is better. However, some bias may exist, as educated people are perhaps more willing to participate in the survey.

Measures

Growth aspirations

Growth aspiration enters our model as the dependent variable of interest. This variable is a latent variable that is not directly observed but inferred from other variables. We use five questions that have been successfully employed in previous studies to measure growth aspiration (for example, Davidsson, Citation1991; Delmar & Wiklund, Citation2008; Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2003). We asked owner-managers whether they expect their business to grow to a large organization that can employ at least 50 people and whether they have the capability to develop the business into a larger organization. We also added questions that captured owner-managers’ aspirations and ambitions to expand their business (Begley & Boyd, Citation1987). The respondents used a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree) to answer the five questions (see ).

Table 1. Measurement of variables

Childhood SES: Parents’ education

The traditional measure for SES includes three items regarding the parents: education, income, and occupation (White, Citation1982). However, in the Tanzanian environment, unbiased information about income is difficult to obtain and a categorization of occupations in terms of classes is not straightforward. Therefore, we used the parents’ education and made the following classification (): no education, primary education, secondary form 1–4, secondary form 5–6, college, university.

Role model: Parents running a business

Empirical studies have noted that entrepreneurs are more likely to come from families in which the parents owned a business (Bosma et al., Citation2012; Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003). Moreover, it is argued that an individual with a parent who owns a business increases not only the likelihood of becoming an entrepreneur but also the likelihood of expanding their business (Hout & Rosen, Citation2000).

Social environment: Place of living during childhood

Previous studies have found that students from rural areas have lower educational and career aspirations than their urban peers. Young people aspire to what they know or can imagine. Due to a lack of success examples and career diversity, the aspirations of rural young people are limited by the geographical and cultural context of their communities (Bajema et al., Citation2002).

Formal education

Regarding the relationship between education level and growth aspiration, studies have shown that entrepreneurs with high levels of education are likely to aspire higher than entrepreneurs who have low levels of education (Davidsson, Citation1991; Gimeno et al., Citation1997; Kolvereid, Citation1992). We use the same classification as used for measuring the parents’ education.

Formal and informal network membership

To gauge social capital we distinguish between informal and professional networking in the model. In order to measure the role of professional networks we asked the respondents whether they were members of the Chamber of Commerce, Federation of Women Entrepreneurs in Tanzania, Tanzania Food and Processing Association, or Vivanda na bishara ndogondogo [Industries and Small Business]. To gauge the role of informal organizations we asked them whether they were a member of tribal, gender (women), religious, or political organizations.

Control variables

From extant literature, we derived several control variables that were taken into account in our model. Previous studies have found that prior paid employment by an entrepreneur increases not only the likelihood of someone starting their own business, but also has the potential to increase the survival rate of the business (Boden & Nucci, Citation2000). Similarly, it has been found that management experience of an entrepreneur in terms of managerial responsibilities prior to entering into the business can affect an entrepreneur’s future aspirations and business performance (Manolova et al., Citation2007). Socialization processes may result in gender differences in the relationship (Brush et al., Citation2019). Therefore, we control for gender. From previous studies we also derive that owner-managers’ growth aspirations are related to firm age (Manolova et al., Citation2007). Similarly, it has been found that owner-manager’s age is significantly related with growth aspirations (Manolova et al., Citation2007).

Empirical approach

We use a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach to analyze the proposed structural relationships because this technique allows us to assess relations between latent constructs (for example, growth aspirations) and measured variables. The observed variables that we use to measure growth aspirations are Likert-scale variables on a five-point scale. Such variables are often characterized as an ordinal approximation of a continuous variable (Johnson & Creech, Citation1983). However, in order to validate our findings and reflect on the ordinal character of the variables for measuring growth aspiration, we performed robustness checks with a generalized outcome model (the generalized structural equation model [GSEM]) which accounts for the ordinal nature of the data.

Findings

Measurement model

We report the descriptive statistics of all variables in . Because our main dependent variable, growth aspiration, is a latent variable, we start by reporting a measurement model for growth aspirations. The results for this measurement model are documented in and we report both estimates, assuming observed variables to be linear and ordinal. We observe that the model fit of the baseline model is much worse in comparison to the saturated model than our estimated measurement model. Next, we also estimated a nonlinear, ordinal measurement model (ordered complementary log-log). As an additional check, we also performed a factor analysis (). The resulting overall test scale has Cronbach’s α = 0.95, and—as indicated by the corresponding α values for each variable—removing a single variable does not substantially influence the Cronbach’s alphas (besides the expected α decrease by shortening the test). The corrected item-total correlations ranged from .776 to .820, indicating that the scale has acceptable reliability.

Summary of our findings

A correlation table of the variables that we use in our estimations can be found in . We also report detailed results of the estimated SEM in : this table provides detailed results of (a) a basic SEM that considers the direct paths of the entrepreneurs’ education, the indicators for professional and informal network membership, management experience, gender, firm age, and the age of the entrepreneur; (b) the proposed conceptual model that includes three variables for inherited cultural capital; and (c) additional models based on post hoc analysis. We also performed, but do not report for brevity, a Wald test for each structural equation that all coefficients excluding the intercept are zero. We summarize our findings in , which is based on our proposed model and also supported by the post hoc analysis that we carried out.

Table 2. Overview of results

The upper part of reports the observed associations between growth aspirations and our measure for different dimensions of inherited cultural capital, institutionalized cultural capital, and social capital. In the remaining part of we summarize our findings concerning the mediating relationships. According to our proposed model, the education of the entrepreneur (institutionalized cultural capital) and the social capital variables (professional and informal network) are supposed to mediate the effect of the inherited cultural capital variables in addition to a direct influence on growth aspirations. Accordingly, the mediating relationships help us to better understand the potential mechanism by which institutionalized cultural capital and social capital influence growth aspirations.

Regarding the direct effects on growth aspirations, we observe that only one of the dimensions of inherited cultural capital (childhood SES) is found to be a determinant for growth aspirations. Next, we find a significant direct effect of institutionalized cultural capital, measured as formal education, on growth aspirations. Regarding the direct effect of social capital on growth aspirations we only observe a significant positive impact of the professional network but not the informal network.

Next, we turn to the mediating effects. Regarding the associations between the different dimensions of inherited cultural capital and potential mediators, we observe that especially the education of the entrepreneur and professional network membership are influenced by inherited cultural capital. More specifically, we observe that the education of the parents, parent’s functioning as role models regarding running a business, and the place of living during childhood influence the level of education of the entrepreneur. Membership in formal networks is only significantly influenced by parents running a business during childhood. However, the Wald test suggesting all coefficients are zero cannot be rejected. Interestingly, we do not find any relationship of the variables that proxy inherited cultural capital on informal networking at the five percent level. This finding is mirrored in the insignificant Wald-test for this equation. Based on our proposed model (model 2 in ) we further test for the presence of mediating effects by calculating corresponding statistics for the direct, indirect, and total effect. We observe that education of the parents has a significant direct relation (0.31) with growth aspirations but no significant indirect relationship, despite parent education displaying a significant association with the education of the entrepreneur.

Next, we find that parents’ functioning as role models has a remaining direct effect on growth aspirations (0.32), which is, however, only significant at the 10 percent level. Complementing this weak direct relation, we find a combined significant indirect effect on aspirations that passes through education of the entrepreneur and professional network membership (0.15). The indirect effect via professional network membership is 0.058* 0.86 = 0.05, and the indirect effect via education of the entrepreneur is 0.42* 0.21 = 0.088. When multiple mediators are present, these partial indirect effects can be derived by multiplying the coefficient for parent role model in the structural equation that explains the education of the entrepreneur and professional networking membership, respectively, with the coefficient of education of the entrepreneur (and professional networking membership) in the structural equation that explains growth aspirations. The total effect of parent role model (0.47) is significant at the five percent level. Accordingly, the proportion of the total effect that is mediated is 0.15/0.47 = 0.32.

Finally, social environment during adolescence, measured by place of living during childhood, has a significant indirect relationship (0.102) with growth aspirations via the education of the entrepreneur. However, the total effect remains insignificant. As suggested by previous literature (for example, Shrout & Bolger, Citation2002), significance of the total effect is not required to detect an indirect mediation effect.

Regarding the overall model quality, we observe that the chi2 value of our proposed model against the saturated model is much lower (chi2 = 267.3) than the chi2 value of the baseline model against the saturated model (chi2 = 2000.9). This indicates that the baseline model, which considers the means and variances of all observed variables and the covariances of the exogenous variables, performs much worse than our proposed model. Finally, we observe that the control variables management experience, age of the business owner, and age of the firm are not influencing growth aspirations. However, a gender effect is confirmed in all the models. This is in line with other literature (Brush et al., Citation2019) and may reflect the effect of the household responsibilities women assume in the Tanzanian context.

Additional post hoc analysis

We performed a number of additional analyses. First, we tested if management experience mediates any of the inherited cultural capital variables. However, we did not find strong support for such a model. Next, we analyzed modification indices for path coefficients and covariances that we omitted in our proposed model. These modification indices are tests for the statistical significance of omitted parameters. Based on these tests, we modified our proposed model by adding a path between education of the entrepreneur and leadership experience, and a covariance parameter for the expectation and the capability to grow in the measurement model. The results for this post hoc analysis are reported in model 3 () and . Please note that the equations for “Education,” “Professional Network,” and “Informal Network” do not change in the post hoc analysis and hence point estimates are therefore the same.

Testing this model displays a noteworthy improvement. The general findings regarding our main variables of interest remain. Interestingly, the post hoc analysis reveals substantial indirect effects of all three dimensions of the inherited cultural capital that we study. More specifically, additional test statistics show that parents’ education, parents’ role model, and the social environment during adolescence influence management experience via the education of the entrepreneur. Further analysis did not reveal additional direct relationships between the three dimensions of the inherited cultural capital and management experience.

Finally, model 4 shows the results of a GSEM that explicitly accounts for the ordinal nature of the variables measuring growth aspiration. These results are presented as a robustness check and validate our findings. We find rather similar results, with one noteworthy exception. In the SEM models, our indicator for “role model” is only significant at the 10 percent level; the GSEM results indicate a positive and significant relationship at the five percent level.

Discussion

The results confirm the importance of the direct effect coming from inherited cultural capital on growth aspirations (H1). In line with expectations, the parents’ education and parents owning a business do have a significant positive, direct effect. This result confirms the principal proposition of this article that inherited cultural capital is playing an important role for businesses operating in a weak institutional environment. Interestingly, the urban/rural context (place of living) does not seem to have a direct effect, although we observe an indirect effect through education of the SME owner. This was expected because access to education is more challenging in rural areas.

The findings also confirm that formal education of the SME owner is influencing growth ambitions (H2). This effect on aspirations may be rooted in two different components. General education seems to facilitate the number of perceived opportunities and therefore may have a positive effect on growth ambitions (Davidsson, Citation1991; Manolova et al., Citation2007). Recalling the weak institutional environment in which they operate, we also expect that general education helps to cope with the ambiguous institutional context (Acquaah, Citation2012; Sutter et al., Citation2013). The second component may be related to what Gimeno et al. (Citation1997) discussed as a higher threshold for the higher educated, implying that the higher educated who start a business will have higher growth aspirations.

In line with previous research, parents’ education coheres with the education level of the children (De Graaf et al., Citation2000). Interestingly, the role model variable (parents owning a business) also has a positive effect on education. We conclude that these results provide support for the third hypothesis that part of the effect of inherited cultural capital is mediated by the effect of formal education of the SME owner on their growth aspirations.

The results of the path analysis confirm that social capital as measured by membership in professional networks is having a direct positive effect on growth ambitions (H4). This result corroborates the findings of Manolova et al. (Citation2007). Membership in more informal nonprofessional networks is not influencing growth aspirations of the business owners at the BoP.

With regard to the last hypothesis, we observe that education of the parents and place of living are not influencing participation in professional networks. We recall that the small number of firms that participate in these networks may affect these results (false negatives may result from a small number of observations). However, parents owning a business do make membership of their children in professional networks more likely (H5).

The results regarding H1, H3, and H5 also show that if entrepreneurship at the BoP can be understood, inherited cultural capital is playing an important role. First, this confirms the relevance of the theoretical approach we adopted. Earlier research on growth aspirations merely neglected this insight. Although this may be understood in environments where the institutional environment is strong (Estrin et al., Citation2013; Welter & Smallbone, Citation2006; Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2003), our results show that it certainly applies to research in weaker institutional environments (Efendic et al., Citation2015; Manolova et al., Citation2007; Puente et al., Citation2017). In weak institutional environments markets are expected to face major deficiencies and the enforcement of the rule of law is expected to be uncertain. These deficiencies have a strong impact on opportunities for severely resource-constrained businesses at the BoP. In such a context, inherited cultural capital can be expected to play an important role in circumventing these challenges. Interestingly, this inherited capital is also influencing formal education and membership in professional networks. This further strengthens the total effect on growth aspirations. Put differently, part of the direct effect of social capital and formal education on growth aspirations is rooted in the social background in which the business owner was raised.

In this respect, it is interesting to further focus on the role of social capital at the BoP. Despite the positive direct effect on growth aspirations, our data also show that only a few (five percent) of the business owners operating at the BoP are member of these professional networks (). This implies that only a small number of the businesses at the BoP are expected to benefit from this capital. Admission fees and the central location (Dar es Salaam) of these professional networks will partly explain this situation. Moreover, a large number of the firms interviewed (33 percent) were still informal (Webb et al., Citation2014) and, therefore, not able to register as a member of a formal professional network. Another, more intuitive, explanation may be derived from the arguments presented by Battilana et al. (Citation2009) that severely resource-constrained actors may not be able to change institutions. Consequently, business owners at the BoP aware of these limitations may lose interest in professional networks.

In Tanzania, we observe that government policy regarding the business environment is focused on professional networks that organize larger formal firms (Acquah Obeng & Blundel, Citation2015). For businesses operating at the BoP, support from the government is negligible and the formal institutional environment is generally perceived as a major challenge. Although we expected that business owners at the BoP might organize themselves into informal local networks, we did not come across powerful groups in the markets under study. It all reflects the limited use at the BoP of networks as instruments to benefit from social capital. Interestingly, our data also show that membership in informal nonprofessional networks is widespread: About 20 percent of the owners are members of a political party, 30 percent are active in a tribal community, while about 40 percent are members of a religious group and 40 percent of the women participate in a women’s organization (Tundui, Citation2012, p. 120). However, we do not find evidence that participation in these networks influences the level of growth aspirations.

Conclusions and implications

In this study, we analyzed growth aspirations of business owners managing firms at the BoP in a weak institutional environment.

This study complements insights from earlier studies in several ways. First, it confirms earlier results that social capital and formal education do have a direct effect on growth aspirations. In the weak institutional context in which these firms compete, education and social capital seem to operate as instruments to protect the interests of the business and to nurture growth ambitions. A first policy implication would be that access to formal education and social capital should be key ingredients for policies that encourage entrepreneurship at the BoP.

The major contribution of this article to the existing body of literature is that our results show that inherited cultural capital is playing a determinant role for the businesses under study. The SES of the parents and the existence of a role model have a direct positive effect on growth ambitions but also have a positive effect on the level of education of the business owners and their access to social capital. Social capital and formal education do play a role as well, but for a good understanding of the formation of growth aspirations the social background is key. This result confirms the relevance of the conceptual model we derived from existing literature and the theoretical insights as proposed by Bourdieu (Citation1986).

We observed that only a few respondents are members of a professional organization. Membership in these organizations may be difficult for BoP entrepreneurs because of limited accessibility, the costs involved, and the effort required. This finding has an important policy implication. In Tanzania, professional networks exist and seem to have a positive influence on growth ambitions. At the same time, we know that these networks focus on larger firms, which makes participation of small business less attractive and results in low membership rates among BoP businesses. From this we derive a second policy implication of this research, as we urge policy makers to assess the possibilities to facilitate the establishment of BoP organizations at the local level. These organizations represent the local small businesses and provide a platform to exchange business ideas, to facilitate opportunity recognition, and to improve access to resources and the further development of entrepreneurial capabilities. Open system intermediaries, as discussed by Dutt et al. (Citation2016), may be helpful to address these institutional failures.

Finally, we acknowledge that this study faces several limitations. The sample is limited and the context is quite specific. Future studies are needed that take into account more specific elements of human capital, social capital, and inherited cultural capital. Similarly, further research may want to dive deeper into the role of the institutional environment for business at the BoP. Two intriguing questions especially call for further research. How is a weak institutional environment influencing businesses at the BoP and how do expected costs and benefits of social capital affect the willingness to invest in social capital by businesses at the BoP?

References

- Acquaah, M. (2012). Social networking relationships, firm-specific managerial experience and firm performance in a transition economy: A comparative analysis of family owned and nonfamily firms. Strategic Management Journal, 33(10), 1215–1228. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1973

- Acquah Obeng, B., & R. K. Blundel. (2015). Evaluating enterprise policy interventions in Africa: A critical review of Ghanian small business support services. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 416–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12072

- Adler, P. S., & S. W. Kwon. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.5922314

- Arregle, J. L., B. Batjargal, M. A. Hitt, J. W. Webb, T. Miller, & A. S. Tsui. (2015). Family ties in entrepreneurs’ social networks and new venture growth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 313–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12044

- Bajema, D. H., W. W. Miller, & D. L. Williams. (2002). Aspirations of rural youth. Journal of Agricultural Education, 43(3), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2002.03061

- Batjargal, B. (2003). Social capital and entreprenurial performance in Russia: A longitudinal study. Organization Studies, 24(4), 535–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024004002

- Battilana, J., B. Leca, & E. Boxenbaum. (2009). How actors change institutions. Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Begley, T. M., & D. P. Boyd. (1987). Psychological characteristics associated with performance in entrepreneurial firms and smaller businesses. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(87)90020-6

- Boden, A. J., & A. R. Nucci. (2000). On the survival prospects of men’s and women’s new business ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00004-4

- Bosma, N., J. Hessels, V. Schutjens, M. Van Praag, & I. Verheul. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.004

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). Forms of capital”. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York.

- Brush, C., L. F. Edelman, T. Manolova, & F. Welter. (2019). A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9992-9

- Bruton, G. D. (2010). Business and the world’s poorest billion – The need for an expanded examination by management scholars. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(3), 6–10. https://DOI:10.5465/AMP.2010.52842947

- Bruton, G. D., D. J. Ketchen Jr., & R. D. Ireland. (2013). Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.05.002

- Bulte, E., R. Lensink, & N. Vu. (2017). Do gender and business trainings affect business outcomes? Experimental evidence from Vietnam. Management Science, 63(9), 2885–2902. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2472

- Davidsson, P. (1991). Continued entrepreneurship: Ability, need, and opportunity as, determinants of small firm growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(91)90028-C

- Davidsson, P., & B. Honig. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

- De Graaf, N. D., P. M. De Graaf, & G. Kraaykamp. (2000). Parental cultural capital and educational attainment in the Netherlands: A refinement of the cultural capital perspective. Sociology of Education, 73(2), 92–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673239

- Delmar, F., & J. Wiklund. (2008, May). The effect of small business managers’ growth motivation on firm growth: A longitudinal study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00235.x

- Dutt, N., O. Hawn, E. Vidal, A. Chatterji, A. McGahan, & W. Mitchell. (2016). How open system intermediaries address institutional failures: The case of business incubators in emerging-market countries. Academy of Management Journal, 59(3), 818–840. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0463

- Efendic, A., T. Mickiewicz, & A. Rebmann. (2015). Growth aspirations and social capital: Young firms in a post-conflict environment. International Small Business Journal, 33(5), 537–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613516987

- Engel, Y., M. Kaandorp, & T. Elfring. (2017). Toward a dynamic process model of entrepreneurial networking under uncertainty. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.001

- Erikson, R., & J. H. Goldthorpe. (2002). Intergenerational inequality: A sociological perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 31‐44. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533002760278695

- Estrin, S., J. Korosteleva, & T. Mickiewicz. (2013). Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 564–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.001

- George, G., J. N. O. Khayesi, & M. R. Tahinyi Haas. (2016). Bringing Africa in: Promising directions for management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59(2), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4002

- Gimeno, J., T. B. Folta, A. C. Cooper, & C. Y. Woo. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 750–783. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393656

- Goel, S., & R. Karri. (2020). Entrepreneurial aspirations and poverty reduction: The role of institutional context. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 32(1–2), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2019.1640484

- Hair, J. F., Jr., W. C. Black, W. J. Babin, R. E. Anderson, & R. L. Tatham. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hout, M., & H. Rosen. (2000). Self-employment, family background, and race. The Journal of Human Resources, 35(4), 670–692. https://doi.org/10.2307/146367

- International Labour Organization. (2003). Tanzanian women entrepreneurs: Going for growth. https://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2003/103B09_58_engl.pdf

- Jacobs, J. A., D. Karen, & K. McClelland. (1991). The dynamics of young men’s career aspirations. Sociological Forum, 6(4), 609–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01114404

- Johnson, D., & J. Creech. (1983). Ordinal measures in multiple indicator models: A simulation study of categorization error. American Sociological Review, 48(3), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095231

- Karnani, A. (2007). The mirage of marketing to the bottom of the pyramid: How the private sector can help alleviate poverty. California Management Review, 49(4), 90–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166407

- Khayesi, J., G. George, & J. Antonakis. (2014). Kinship in entrepreneur networks: Performance effects of resource assembly in Africa. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(6), 1323–1342. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12127

- Kolvereid, L. (1992). Growth aspirations among Norwegian entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(92)90027-O

- Lent, M. (2020). Everyday entrepreneurship among women in Northern Ghana: A practice perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(4), 777–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1672707

- Light, I., & L. P. Dana. (2013). Boundaries of social capital in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12016

- Liguori, E., & J. S. Bendickson. (2020). Rising to the challenge: Entrepreneurship ecosystems and SDG success. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 1(3–4), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/26437015.2020.1827900

- Manolova, T., N. M. Carter, I. M. Manev, & B. S. Gyoshev. (2007). The differential effect of men and women entrepreneurs’ human capital and networking on growth expectancies in Bulgaria. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 31(3), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00180.x

- McMullen, J. S. (2011). Delineating the domain of development entrepreneurship: A market-based approach to facilitating inclusive economic growth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 185–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00428.x

- Meyer, K. E., S. Estrin, S. K. Bhaumik, & M. W. Peng. (2009). Institutions, resources, and entry strategies in emerging economies. Strategic Management Journal, 30(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.720

- North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97

- Prahalad, C. K., & A. Hammond. (2002, September). Serving the world’s poor, profitably. Harvard Business Review, 80(9), 48–57. https://hbr.org/2002/09/serving-the-worlds-poor-profitably

- Puente, R., M. A. Cervilla, C. G. González, & N. Auletta. (2017). Determinants of the growth aspiration: A quantitative study of Venezuelan entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 48(3), 699–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9791-0

- Qureshi, I., G. M. Kistruck, & B. Bhatt. (2016). The enabling and constraining effects of social ties in the process of institutional entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 37(3), 425–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615613372

- Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9215-5

- Shrout, P. E., & N. Bolger. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

- Stam, W., S. Arzlanian, & T. Elfring. (2014). Social capital of entrepreneurs and small firm performance: A meta-analysis of contextual and methodological moderators. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 152–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.01.002

- Sutter, C. J., J. W. Webb, G. M. Kistruck, & A. V. G. Bailey. (2013). Entrepreneurs‘ responses to semi-formal illegitimate institutional arrangements. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.03.001

- Thornton, P. H., D. Ribeiro-Soriano, & D. Urbano. (2011). Socio-cultural factors and entrepreneurial activity: An overview. International Small Business Journal, 29(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610391930

- Tundui, H. P. (2012). Gender and small business growth in Tanzania: The role of habitus. University of Groningen.

- United Republic of Tanzania. (2006). Integrated labour force survey 2006. National Bureau of Statistics.

- United Republic of Tanzania. (2007a). Household budget survey 2007. National Bureau of Statistics.

- United Republic of Tanzania. (2007b). Business survey 2007. National Bureau of Statistics.

- Uzo, U., & J. Mair. (2014). Source and patterns of organizational defiance of formal institutions: Insights from Nollywood, the Nigerian Movie Industry. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 8(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1171

- Webb, J. W., R. D. Ireland, & D. J. Ketchen. (2014). Toward a greater understanding of entrepreneurship and strategy in the informal eonomy. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 8(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1176

- Welter, F., & D. Smallbone. (2006, July). Exploring the role of trust in entrepreneurial activity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(4), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00130.x

- White, K. R. (1982). The relation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 91(3), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.461

- Wiklund, J., & D. A. Shepherd. (2003). Aspiring for, and achieving growth: The moderating role of resources and opportunities. Journal of Management Studies, 40(8), 1911–1941. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-6486.2003.00406.x

- Wiklund, J., P. Davidsson, & F. Delmar. (2003, Spring). What do they think and feel about growth? An expectancy-value approach to small business managers’ attitudes toward growth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(3), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.t01-1-00003

- World Bank. (2017). Doing business 2017, equal opportunity for all. World Bank.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics

Table A2. Measurement model for growth aspirations

Table A3. Measurement of growth aspirations (Factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, and correlations)

Table A4. Correlation matrix

Table A5. Results of the generalized structural equation model

Table A6. Membership in professional networks