ABSTRACT

The framing of processed foods by groups of positive, negative or balanced online actors expresses the public mood about processed food and at the same time influences public views and policy. In this paper, we studied the framing of processed food by online sentiment coalitions – groups of online actors that are united by their positive, negative, or balanced stance towards processed food. We innovatively integrated digital methods with textual and visual analyses of 164 webpages and 344 online visualizations published by a total of 89 actors, such as academics, food technologists, journalists, governmental actors, NGOs, industry actors, nutrition specialists. The analysis shows that the online “dream” coalition of processed food framed it in a way to convey the human aspects of food processing: processed food is understood as a way to improve human lives, and photographs of industrially processed food produced by humans show it is not as industrialized as often thought of. The online “nightmare” coalition of processed food framed it primarily as posing health threats and accompanied this with photographs of unhealthy but colourful foods. The balanced coalition gave a balanced description of the benefits and drawbacks of processed food and accompanied this frame with photographs emphasizing the difficulty in making food choices. Extending the knowledge about the ways sentiments about processed food are communicated online is essential as it provides important insights into people’s understanding of the notion of “processed food” and the meaning that is given to it by various online interpretive communities.

1. Introduction

In everyday talk, “processed food” often has a negative connotation: it is associated with salty, unhealthy, industrially manufactured foods that in the academic literature would be classified as ultra-processed foods (see Text box 1 for explanation). Very often processed foods are opposed to “natural” or “clean” foods (Baker & Walsh, Citation2020; “clean” food is “unprocessed food considered to be as close to its whole form and natural state as possible”, Lupton Citation2018, p. 71). However, preparing and cooking foods in our own kitchens – cutting, heating, adding sugar and salt, turning into a puree – is also food processing. Despite this imprecise use of the term processed food in everyday speak, these discursive and visual (mis)representations of processed food in media and new-media are interesting to study as they depict how an online general public is interpreting processed foods. In addition, since the internet is an important source of information for the general public, these (mis)representations are influential on public opinion formation and even political decision-making (Clancy & Clancy, Citation2016; Rojas-Padilla et al., Citation2022).

Text box 1 – Processed food: purposes and definitionsThe availability of sufficient and healthy food has been an issue ever since people started walking the face of the earth. Primitive methods of food processing were necessary, in prehistoric times, for the survival of humans. Later, when humankind has systematically been able to breed improved versions of grains and to farm animals, maintaining the quality of the obtained foods has been an uphill struggle dealt with by applying primary storage methods but also processing techniques such as drying, salting, and fermenting. Food processing allowed to build supplies that sometimes – quite literally – carried communities through the harsh winter.In current times, food processing is much more diverse and industrialized and has become a major market sector that serves various purposes such as extending shelf life, improving nutritional value and safety, and increasing convenience and palatability (Huebbe & Rimbach, Citation2020). However, the highly mechanized and less traditional manufacturing processes have created a sense of ambivalence towards foods produced in a factory. Complicated facts about foods, which change over time, and the enormous complexity of the food production and consumptions system contribute even more confusion and scepticism to this bewildering situation.In 2009, a group of nutrition and health researchers at the University of São Paulo proposed a new way of categorizing foods that is based on the extent and purpose of the processing and coined a new food category of ultra-processed food (Fraanje & Garnett, Citation2019). Next to subsequent study that used this categorization system and associated the consumption of ultra-processed foods with chronic non-communicable diseases (e.g. Marrón-Ponce et al., Citation2019; Martínez Steele et al., Citation2019), the classification system was also criticized for being impossible to use (Gibney et al., Citation2017), and there is an ongoing scholarly debate about whether the type and level of processing should be considered as a criterion for food classification and replace a more traditional food categorization that is based on nutrient value and food components (Eicher-miller, Fulgo et al., Citation2012; Jones Citation2019; Poti et al., Citation2015).Among scientists that categorize foods based on the level of processing, there is no widely accepted categories and definitions, and there are discrepancies between various classification systems (Bleiweiss-Sande et al., Citation2019). Yoghurt can serve as an example. It is considered unprocessed or minimally processed, according to NOVA classification system (Monteiro et al., Citation2019); it is considered basic processed, according to a classification system of researchers from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (this classification system also has an “unprocessed/minimally processed” food category, Poti et al., Citation2015); it is considered ready-to-eat, according to the International Food Information Council (IFIC, Citation2010). In everyday talk the term “processed food” refers to foods belonging to the higher processing-level categories in the various classification systems: those foods that are mass-produced, contain industrially formulated mixtures, and few ‘natural’ ingredients, e.g. ‘ready-to-eat processed foods’, ‘prepared foods/meals’ (Eicher-miller, Fulgo et al., Citation2012), ‘ultra-processed food’ (Monteiro et al., Citation2019), ‘highly processed food’ (Poti et al., Citation2015).

The rapidly growing popularity of food on digital platforms (De Solier, Citation2018; Lewis, Citation2018; Lupton, Citation2020) turned these platforms into key spaces to discuss food-related issues, to the extent that “thinking about food through digitized media has become mainstream” (Rousseau, Citation2012, p. 92). Digitized information about food is accessed through internet search engines (Lupton, Citation2018), which present information provided by various actors such as nutrition specialists, policymakers, academics, industry, bloggers, and NGOs. These actors share knowledge and also manifest their views, sometimes by disclosing (visual) information that otherwise remains hidden or inaccessible (Schneider et al., Citation2018). Online, visualizations are used extensively to represent food (Lupton, Citation2020); producing visualizations or engaging with them is everyday practice (Lewis, Citation2018). Online visualizations communicate meanings about food-related issues and may enhance or limit the credibility of the information given about food (Baker & Walsh, Citation2020).

However, (visual) information shared on the internet not only gives insights into how a digital public understands food issues but also influences the way people think about food and discuss it (Lupton, Citation2018). Visual and textual information spread in the digital world shapes public views (Clancy & Clancy, Citation2016) and policies (Metze, Citation2020; Wozniak et al., Citation2017). This digital world is often seen as experimental (Marres, Citation2017, p. 147), where the boundaries between experts and laypeople are re-defined (Lupton, Citation2018; Rousseau, Citation2012), and information is heavily mediated by algorithms (Lewis, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2019). Hence, the diverse interpretations of food online may not only represent expert knowledge and the exiting digital cultures of processed food but it can also affect the societal debate about it, which is related to decision-making, as happened, for example, in the case of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and other food-related issues (De Cock et al., Citation2016; Inghelbrecht et al., Citation2014).

Although framing in text and visuals in newspapers and new media is recognized as influential in various academic studies (Krause & Bucy, Citation2018; O’Neill, Citation2013; Redden, Citation2011), actors’ sentiments in combination with these visual and textual framing has not received much scholarly attention. To fill this gap, this paper sets out to further develop the notion of online sentiment coalition – a group of actors that predominantly express positive, negative, or balanced sentiment about an issue on their websites – and examines the particular ways in which they frame processed food. This will provide insights into people’s understanding of the notion of “processed food” and the meaning that is given to it by various online interpretive communities (see Yanow, Citation2000).

The research question in this paper is: how do online sentiment coalitions visually and textually frame processed food? To answer this question, we studied (1) which online actors belong to which sentiment coalitions and (2) what discursive and visual framings they use.

2. Conceptual framework: Online sentiment coalitions and their textual and visual framing

Inspired by automated sentiment analysis, we categorize online publics (Marres & Rogers, Citation2005) that form around processed food in three groups: those that express and share predominantly positive sentiment, negative sentiment, and a more balanced sentiment about processed food. In automated sentiment analysis, sentiments are typically classified as positive (pro-), negative (anti-), or neutral (Kwak & Grable, Citation2021; Yigitcanlar et al., Citation2020), and emotion in text is recognized based on positive or negative words (Cambria et al., Citation2017). Hence, in automated sentiment analysis, a binary classification of emotions is used, which is different from affective analysis that labels a set of emotions. In framing analysis, this binary approach is referred to as tone-of-voice which indicates a positive, negative, or neutral stance in media reporting on particular issues (e.g. Baumgartner et al., Citation2008; Kuttschreuter et al., Citation2011). In this study, we follow this binary division and study what groups of actors are present on the internet, based on their discursively expressed positive and negative stances towards processed food. As such, we are interested in online sentiment coalitions that we labelled “a dream” (positive), “a nightmare” (negative), and a balanced coalition.

Next to their discursively expressed sentiments, these groups of actors can also frame processed food in different ways. Framing can take place discursively but also visually. Framing is a process in which some aspects of reality are selected and given greater emphasis or importance so that the problem is defined, its causes are diagnosed, moral judgements are suggested, and appropriate solutions and actions are proposed (Entman, Citation1993, p. 52). Stemming from semiotics from Saussure, both discursive and visual framing can take place by use of denotive signs and connotive signs (Saussure in Richter, Citation1998). Denotive signs are those that try and name or depict reality. For example, the word rose is referring to the flower, or a picture of a rose can depict this particular flower. The denotive signs can be studied through content analysis: one can, for example, identify what a word is referring to or what is in the picture: a person, an animal, industry, a landscape, and that refers to a “real” thing (a person, an animal, etc.; Rose, Citation2016, p. 121). There is, however, a second layer of meaning: the meaning that is carried by connotive signs which is the cultural meaning of the words, sentences, or the visuals (Rose, Citation2016). For example, in the controversy over GMOs, the use of the word biohazard and the use of its symbols in the depiction of GMOs stimulated interpreting those as toxic (Clancy & Clancy, Citation2016). The metaphor or symbol in words or a picture is then representing an idea or a mental construct – in our words, a particular interpretation, framing, of the issue.

To summarize, online sentiment coalitions are networks of online actors tied together around a sentimental storyline about a particular issue. Online sentiment coalitions visually and textually frame an issue. Both the textual and visual framing can take place through the use of denotive or connotive signs.

3. Method

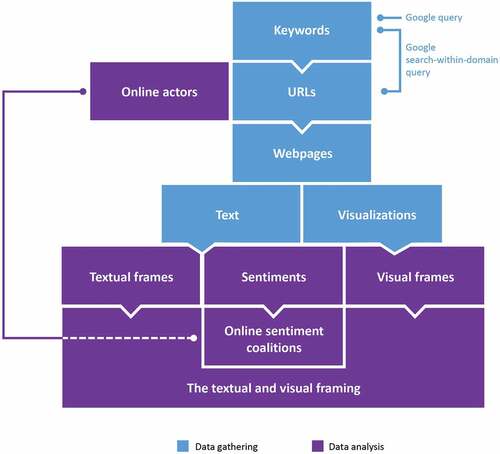

To answer the research question, we followed the steps visualized in and elaborated below.

3.1. Data gathering

To construct a dataset, we queried GoogleFootnote1 for pages in English containing the terms “processed food” and “food processing”, which were identified in preliminary research as the most prevalent sets of keywords that actors use online when referring to processed food. To include dominant online English-speaking voices, the queries were conducted in the two largest English-speaking nations in the Western world (List of Countries by English-Speaking Population, n.d.), namely, the United States and the United Kingdom, and their 50 top-ranked results were integrated. This list was cleaned of duplicates and URLs that were unavailable or URLs that did not include content about processed food. The cleaned URL list was used for search-within-a-domain Google queries with the terms “processed food” and “food processing”. The two top-ranked pages from every URL that contained textual information about processed food and visualizationsFootnote2 were included in our dataset, which ultimately contained 164 web pages and their 344 visualizations.Footnote3 We downloaded those pages (text + visuals) into Atlas.ti software to further analyse them.

3.2. Data analysis

Our unit of analysis was a page (web page) that belongs to a particular actor and communicates a particular sentimental storyline.

We first coded the actor to which every page belonged and categorized the actors. We adapted the categories suggested by Cullerton et al. (Citation2016), acknowledging the emergence of new actor categories through new media (Vaast et al., Citation2013) (see Supplemental Material, Appendix 1).

In the second step, we coded for the overall sentiment expressed in each page based on a manual analysis of the complete text, which is valuable for revealing the valence of emotions evoked from it (Lappeman et al., Citation2020), and the reading of the title of the page, which may place the page’s audience in a particular relationship with its content (O’Neill, Citation2013).

Following this manual sentiment analysis, we constructed the online sentiment coalitions: we grouped the actors that shared a predominantly positive, negative or balanced sentiment about processed food.

The next step was analysing the textual framing. We coded the text of the pages of each sentiment coalition for particular framings of processed food (see supplemental material, Appendix 2). A first set of frames was defined deductively based on academic papers about food technology issues (Aschemann-Witzel et al., Citation2019; Marks et al., Citation2007; Nisbet & Huge, Citation2007; Nisbet & Lewenstein, Citation2002; Oleschuk, Citation2020). These frames were: “environmental harm”, “environmental opportunity”, “health opportunity”, “health threat”, “home cooking”, “many possibilities”, and “safety concerns”. New frames were added inductively along with the analysis. These were: “food security”, “injustice”, “nutritional value”, “safety standards”, and “lack scientific evidence”.

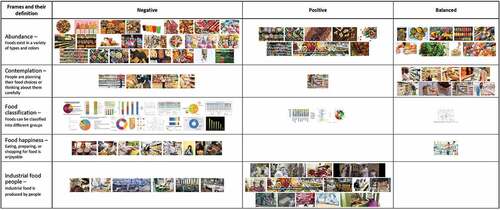

Next, we coded for (1) type of visual (e.g. photograph, infographic),Footnote4 (2) the content (“what is depicted?” e.g. people, food),Footnote5 and (3) the visual frame. The visual frames were interpreted inductively based on the reading of denotive and connotive signs. In denotive reading, the visual was interpreted “literally” (see also “denotative content”, O’Neill, Citation2013, p. 13), for example, a visualization portraying happy people involved in food-related activities was coded with the visual frame “food happiness”. Frames based on denotive reading were: “abundance”, “contemplation”, “food classification”, “food happiness”, “industrial-food-people”. In connotive reading, implicit meaning, usually culture-dependent, was revealed (see also “connotative content”, O’Neill, Citation2013, p. 13), for example, a woman who holds her head in a way that implies she has a headache was coded with the visual frame “unpleasantness”. Frames based on connotive reading were: “body care”, “unpleasantness”.

Finally, we analysed the textual and visual framing of the three sentiment coalitions.

4. Results: Framing the dream, nightmare, or providing information

4.1. Online sentiment coalitions

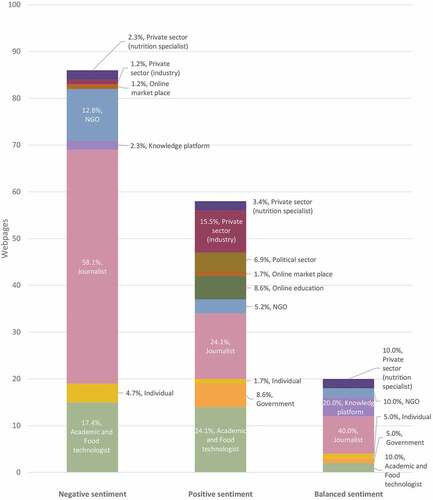

Overall, the online negative sentiment coalition about processed food was the largest one in our data set (). We can also see that “journalist” was the most prominent actor category among the negative coalition and constituted more than half of the coalition (58%, ), meaning that a lot of journalists (old-media, new-media, and professional, see Supplemental Material, Appendix 1) were expressing negative sentimental storylines. In the negative coalition, the group “academic and food technologist”Footnote6 was the second-biggest actor category, and “NGO” was the third. The remaining pages in this coalition belonged to “individual”, “private sector (nutrition specialist)”, “knowledge platform”, “private sector (industry)”, and “online market place” actors.

In the positive sentiment coalition, two actor categories were the biggest: “journalist”, similar to the negative coalition, and “academic and food technologist” (). These two categories together constituted about half of the coalition. “Private sector (industry)” was the next biggest category, followed by “government” and “online education”. The remaining pages belonged to “political sector”, “NGO”, “private sector (nutrition specialist)”, “individual”, and “online market place” actors.

In the balanced coalition, again the most prominent actor category was “journalist” (40%), followed by “knowledge platform”. The two categories together constituted more than half of the coalition (). The remaining pages in this coalition belonged to “academic and food technologist”, “private sector (nutrition specialist)”, “NGO”, “government”, and “individual” actors.

4.2. Textual and visual framing by three online sentiment coalitions

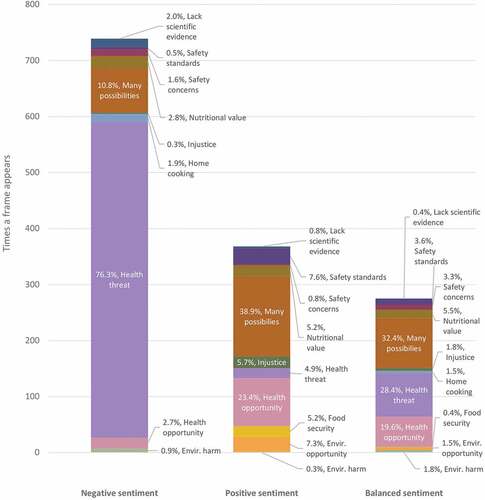

4.2.1. Framing the nightmare: Health threats

We identified ten discursive storylines in the pages of this negative sentiment coalition. In this coalition, processed food was most prominently framed as a “health threat” (), which means that processed food is most of all considered a health threat because there are unhealthy ingredients and that their intake should be limited or avoided. For example, a new-media journalist stated that “all those processed chemicals [that are found in processed foods] can affect mood because the ‘foods’ aren’t actually giving your body any adequate nutrition; you’re getting toxic ingredients, instead”.Footnote7 This discursive framing also included advice on how to avoid the intake of these “unhealthy processed foods”. For example, advice given was to “check the label. The longer the ingredient list, the more processed a food is. If most of the ingredients are hard-to-pronounce chemicals instead of actual food, it’s a safe bet that food is heavily processed”.Footnote8 Some online actors tied the unhealthy frame to the idea of food companies that manipulate consumers and try to increase their intake of unhealthy processed food. For example, an academic actor wondered “why then are U.S. food marketing budgets overwhelmingly used to promote sales of nutrient-poor products like sodas and sweetened breakfast cereals?”.Footnote9

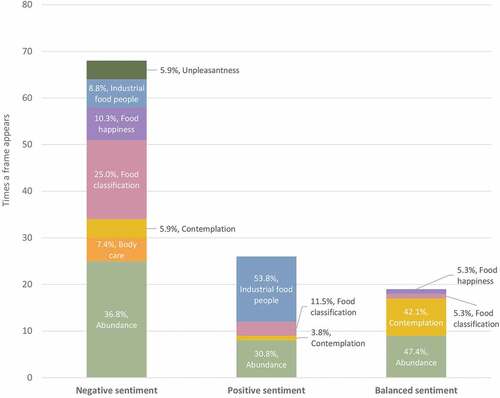

In the negative sentiment coalition, which framed processed food as unhealthy, there was extensive use of visualizations with the visual frame of “abundance”, followed by the “food classification” frame (see below; ). “Abundance” is a frame of foods that exist in a variety of types and colours. It communicates an idea of countless options when making food choices and can be associated with food security but also with the idea of too much food. In our dataset, the “abundance” visual frame was in photographs portraying food by means of what was seen as staging a scene or choosing a particular angle that emphasized variety. In those photographs, foods were neatly organized on a table and captured, mostly, from top-view, or they were in their natural place, filling the whole camera frame, and creating a non-hierarchical frame with many elements (). In the negative coalition specifically, those photographs were of foods typically considered as processed or even ultra-processed (see, Da Costa Louzada et al., Citation2017, p. 114), such as packaged foods, pizza, crisps, French-fries, and candies (, see also the discussion below).

Figure 5. Visual frames in the three sentiment coalitions (for the visualizations as they appear in their URLs see supplemental material, Appendix 3).

“Food classification” is a frame of foods that are classified into different groups. In our dataset, the “food classification” visual frame was in visualizations of a specific type, namely, diagrams (). The use of diagrams is prevalent in scientific publications (Perini Citation2005, p. 913), and, therefore, diagrams can be considered as conveying scientific information. Accompanying the unhealthy frame with extensive use of “scientific” visual frame might be a way in which actors of the negative coalition try to gain legitimacy by presenting themselves as capable of producing scientific knowledge (Schwarz, Citation2013).

4.2.2. Framing the dream: Possibilities and health benefits

In the positive sentiment coalition, the framing of processed food was most of all done by emphasizing its “many possibilities” (). In this framing, it is emphasized that food processing enables various improvements for humans by, for example, improving taste, enhancing convenience for consumers, and allowing for greater food choice and diet diversity. For example, it was expressed that “without processed foods, we would never have the huge variety of foods that we have available to us today”.Footnote10

Next to the new possibilities in creating new (convenient) foods, another quite present framing in the positive coalition was “health opportunity”. In this frame, processed food was presented as most of all benefiting human health by, for example, improving nutritional value or by keeping food safe for human consumption (by adding preservatives). For example, in one of the pages it was stated “in most cases, food processing ensures food safety and nutrition”.Footnote11

This positive framing of processed food as providing many opportunities for more safe, convenient, and healthy foods, was commonly accompanied by visuals that were photographs depicting people involved in the preparation of food in a factory, warehouse, or institutional food service in industrial settings (the “industrial food people” frame, see, ). Some of the photographs presented people’s faces or upper bodies, whereas others presented only their hands (). These visuals seemed to frame processed food as less industrial and more human as often depicted; when people are included in photographs of industrial food preparation, it might make the process of industrial food preparation more personal, and therefore easier to relate to.

4.3. Framing balanced sentiment

In the balanced coalition, the framing of processed food was commonly as providing “many possibilities” (benefits) in combination with the framing of processed food as being a “health threat” (). For example, it was stated that “tertiary food processing [the commercial production of ready-to-eat or heat-and-serve foods] has been criticized for promoting overnutrition and obesity, containing too much sugar and salt, too little fibre, and otherwise being unhealthful in respect to dietary needs of humans and farm animals”, but also that “many forms of processing contribute to improved food safety and longer shelf life before the food spoils”.Footnote12 In some pages, this balanced frame was complemented by the “nutritional value” frame, according to which nutritional value or energy density per type of processed food should be assessed in order to be able to judge if the food product is healthy or not. For example, a new-media journalists claimed that “the best way to tell the difference between healthy refined food and not so healthy refined food is by doing a little nutritional sleuthing (as in label reading)”.Footnote13

This textual framing was commonly accompanied by an “abundance” or “contemplation” visual frame. “Abundance” was communicated with a mixture of visualizations – some portray foods perceived as industrial and others portray foods perceived as natural. “Contemplation” was present in photographs portraying people reading food labels, looking at a shopping list while shopping for food, and scrutinizing a food or seeming to be thinking seriously about it when taking it off the shelf (). Hence, the mixed message about processed food as having benefits but also possible downsides was combined with a visual framing of people trying to make choices and also with having enough food. This visually frames processed food as leading to food-choice hesitancy but also to have enough food, or even abundant food.

The main findings are summarized in .

Table 1. Summary of the results.

5. Discussion

Our results show that the positive, negative, and balanced sentiment coalitions emphasized different aspects of processed food both in their textual and visual framing ().

If we compare the textual framing across the three sentiment coalitions, we see that processed food as providing “many possibilities”, the most dominant frame in positive pages, was also used in the other coalitions’ pages, even the negative one. Very often in the negative sentiment coalition, possible benefits were also mentioned. That could be related to the fact that this coalition was composed of many journalists. However, various types of actors in the negative coalition framed processed food as also offering many possibilities. For example, a private consultancy mentioned that “while some foods are processed to the point that they’re barely recognizable, others are only modified to ensure they are edible, clean, and convenient”.Footnote14 Hence, overall, the negative sentiment coalition framed a negative message in a more balanced way than the way the positive coalition framed a positive message. Overall, the positive sentiment coalition framed processed food in optimistic ways and refrained from mentioning possible drawbacks. This might indicate that actors are more cautious when communicating a negative message about processed food than a positive message, and might be related to the fact that in many countries, the dietary share of (ultra-)processed foods is significant (Fiolet et al. Citation2018; Euridice Martínez Steele, Euridice, M, Swinburn, Monteiro Citation2017), and communicating an intolerant negative message about these foods would mean opposing a prevailing eating practice. Further research could investigate the framing of positive and negative messages about food technologies that are not (yet) widespread. In addition, for practitioners in the processed food positive coalition, it could be advised to also show the possible downsides of processed food – textually and visually, to communicate a more balanced frame of it.

If we compare the visual framing, we see that online actors from the negative coalition told a story of being surrounded by unhealthy and visually attractive processed food; online actors from the positive coalition narrated a story of human food industry; online actors from the balanced coalition narrated a story of food-choice hesitancy. In digital food cultures literature, visuals are indeed acknowledged as adding information to the story told in the text (De Solier, Citation2018), and both textual and visual digital content are considered as meaningful elements in people’s reflection on habits and preferences (Lupton, Citation2018, Citation2020) and also in the attempt to change those (the so-called “digital food activism”, Schneider et al., Citation2018). In visual framing literature, visuals are considered as powerful framing devices, equally important or even more important than text (Metze, Citation2018; Rodriguez & Dimitrova, Citation2011). Hence, attending to the visual framing when investigating the expression of sentiments, online, facilitates an important extension of the knowledge about the ways sentiments are communicated. This knowledge can lead to insights on how the (online) public understands contested food-related issues and the (dynamic) public mood about them.

Our results also show the benefits of manual sentiment analysis in combination with framing analysis. The two types of analyses together support the study of sentiments while applying a broad definition of sentiment, which entails noticing emotional expressions. Visual framing analysis, specifically, complements well manual sentiment analysis because visual framing is often considered as powerful particularly because of its emotional effect (Rodriguez & Dimitrova, Citation2011). This is even more true when the framed topic is controversial (Metze, Citation2018).

Through the study of the expressed sentiments about processed food and the framing of it on the internet – in so-called “food media” (Goodman et al., Citation2017), we shed light on the outcome of visual choices made by different actors, deliberately or not, when communicating a message. Food media plays a critical role in the dynamic process of producing food knowledge that in turn influences the understanding of the food system and the perception of specific foods as, for example, healthy or sustainable (Goodman et al., Citation2017). Therefore, a better understanding of those visual choices can contribute to the understanding of the way in which conflicting knowledges about processed food are spread and gain credit. For example, in our study, the fact that a “scientific” visual frame of “food classification” was used, most of all, in the negative coalition stands out against the fact that this coalition did not have a big share of academics and food technologist. This fact is interesting given visualizations’ capacity to affect the perceived credibility of online food information (Baker & Walsh, Citation2020). This is important especially since, in the digital environment, there is no longer distinguish between a sender and a receiver: a member of the audience of a visual can become a producer (Van Beek et al., Citation2020), and the boundaries between experts and laypeople are re-defined (Lupton, Citation2018; Rousseau, Citation2012).

The results also indicate that in web searches, the online public is more likely to encounter content about processed food in a negative context than in a positive or balanced context and that this information is provided mostly by journalists. Of course, limiting our data to the top-ranked Google results has limitations because of Google’s black-boxed algorithm, which privileges certain pages over others (Rogers, Citation2019, p. 109). Hence, the fact that among the top-ranked Google results, more pages were communicating negative sentiment than any other sentiment and the fact that “journalist” was the biggest actor category in all coalitions might be an outcome of the tendency to click on results with a negative message or results with information provided by journalists. In further research, better data gathering and data reductions strategies that are less dependent on Google’s algorithm would be preferable for this type of research.

Our findings suggest that examining the visual qualities and techniques of visualizations can deepen the understanding of framing processes. Thus, for example, examining the colours used when framing food in a negative way expanded the findings, that is, the complete message revealed was that not only processed food is unhealthy but it also surrounds us and is visually attractive. In addition, the revealing of frames based on both denotive and connotive reading of signs, textual or visual, leads to a rich coding scheme and comprehensive results. Further in-depth studies into the denotive and connotive signs in both text and visuals by, for example, better including the role of specific word or colour used and the role of symbols, metaphors, and cultural interpretations, could further improve our study.

In addition, there might be hidden biases in our dataset that can be overcome by using, for example, our own developed scraper, sentiment and topic analyser. Other methods, such as interviews and surveys, may provide interesting insights into why actors talk about processed food as they do, or why they choose particular visuals with their stories. This study does not give insights into intentions (or a lack of those) when selecting visualizations that frame processed food in a particular way, nor does it examine the awareness of the emotional effect visualizations have (Krause & Bucy, Citation2018; Lilleker et al., Citation2019). Last but not least, the results of this exploratory study are culturally biased since we had to limit our data to English. Further research should construct a broader dataset that includes sources in languages other than English and from non-Western countries.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we investigated how “dream”, “nightmare” and balanced online sentiment coalitions textually and visually frame processed food. We studied 89 online actors and their 164 webpages. We extracted from the pages text and 344 visualizations about processed food. The results show that the negative coalition was most dominant. This coalition framed processed food as posing health threats due to unhealthy ingredients that their intake should be limited or avoided. In the negative coalition, compared to other coalitions, more online actors supported this framing with data visualizations suggesting that their claims are supported by scientific evidence, and more online actors supported this framing with photographs of visually attractive processed foods. The slightly less dominant positive coalition framed processed food as providing a health opportunity and allowing many possibilities for improvement of taste, greater convenience and food choice for consumers, and diet diversity. In the positive coalition, compared to other coalitions, more online actors supported this framing with photographs that depict humans preparing foods in industrial environments. In the balanced coalition, processed food was framed as providing a health opportunity and allowing many possibilities – as was the case in the positive coalition, but also as posing possible health threats. In the balanced coalition, compared to other coalitions, more online actors supported this framing with visualizations that emphasize the difficulty in making food choices.

The dream and nightmare views of processed food will most likely remain prevailing in society, given that “mass-produced food will remain a powerful part of culture” (Bentley & Figueroa, Citation2018, p. 93). Hence, investigating the various meanings that are given to processed food by different actors is essential. In addition, this study also adds an investigation of online coalitions and their textual and visual framing to a recent study that sees the way in which the digital is entangled with food as an expression of the complex relationship between the digital and our daily life (Lewis, Citation2018; Rousseau, Citation2012).

Appendix

Appendix 1: Actor categories

Appendix 2: Textual (discursive) frames

Appendix 3: Visualization URLs

The visualizations appear in Figure 5

URLs of the visualizations appear in Figure 5

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Yara de Koning, Elaine Teixeira Rabello, Eduardo Rojas Padilla, and Filip de Blois for the collaborative visualization typification undertaken during a series of project meetings in 2020. A previous version of this paper was presented at the 13th Interpretive Policy Analysis Conference, June 2021. We are grateful to the participants in this conference for their feedback. We are also greatly indebted to Public Administration and Policy group members and to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

[1] We opted for Google, the dominant web search engine, repurposed by Rogers (Citation2019) as an epistemological machine for conducting social research, and we enclosed queries within double quotation marks (“unambiguous queries”, see, Rogers Citation2019, pp. 32–33). To mitigate Google’s biases, we searched anonymously (logged out of any Google account), using a clean (no cash or cookies) instance of a web browser, with search settings changed from current region (that prioritizes city-level results) to national level.

[2] We did not include webpages in a PDF format, as this format contains layouts that are often inappropriate for the type of analysis conducted.

[3] To avoid over-representation of a particular actor, we limited the scraping of images from a particular URL to the first 10 images.

[4] Visualization-type codes were adapted from Morseletto (Citation2017) and from a series of project meetings in which the researchers coded images for their type and discussed disagreement until consensus was achieved.

[5] For the content analysis method, see, Bell (Citation2001) and Rose (Citation2016).

[6] Academics and food technologists are grouped together. However, there were no food technologists in our negative coalition.

[7] Source: https://www.eatthis.com/stop-eating-processed-foods accessed 15 February 2021.

[8] Source: https://www.lhsfna.org/index.cfm/lifelines/may-2019/the-many-health-risks-of-processed-foods accessed 25 February 2021.

[9] Source: http://www.foodsystemprimer.org/food-and-nutrition/food-marketing-and-labeling accessed 15 February 2021.

[10] Source: https://www.srnutrition.co.uk/2018/10/processed-foods-the-pros-and-cons accessed 10 March 2021.

[11] Source: https://www.fooddive.com/spons/the-truth-about-processed-food-1/553052/ accessed 10 March 2021.

[12] Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Food_processing accessed 15 February 2021.

[13] Source: https://www.verywellfit.com/are-all-processed-foods-unhealthy-2506393 accessed 15 February 2021.

[14] Source: https://nutritionstripped.com/ultra-processed-foods accessed 15 February 2021.

References

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., Varela, P., & Peschel, A. O. (2019). Consumers’ categorization of food ingredients: Do consumers perceive them as ‘clean label’ producers expect? An exploration with projective mapping. Food Quality and Preference, 71(June 2018), 117–128. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.06.003.

- Baker, S. A., & Walsh, M. J. (2020). You are what you instagram: Clean eating and the symbolic representation of food. In D. Lupton & Z. Feldman (Eds.), Digital food cultures (pp. 53–67). Routledge.

- Baumgartner, F. R., De Boef, S. L., & Boydstun, A. E. (2008). The Decline of the Death Penalty and the Discovery of Innocence. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511790638.

- Bell, P. (2001). Content analysis of visual images. In T. Van Leeuwen & C. Jewitt (Eds.), Handbook of visual analysis (pp. 10–34). Sage.

- Bentley, A., & Figueroa, S. L. (2018). A history of food in popular culture over the life span. In K. LeBesco & P. Naccarato (Eds.), The bloomsbury handbook of food and popular culture (pp. 83–95). Bloomsbury.

- Bleiweiss-Sande, R., Chui, K., Evans, E. W., Goldberg, J., Amin, S., & Sacheck, J. (2019). Robustness of food processing classification systems. Nutrients, 11(6), 1344. doi:10.3390/nu11061344.

- Cambria, E., Das, D., Bandyopadhyay, S., & Feraco, A. (2017). Affective Computing and Sentiment Analysis. In E. Cambria, D. Das, S. Bandyopadhyay, & A. Feraco (Eds.), A Practical Guide to Sentiment Analysis (pp. 1–10). Springer.

- Clancy, K. A., & Clancy, B. (2016). Growing monstrous organisms: The construction of anti-GMO visual rhetoric through digital media. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 33(3), 279–292. doi:10.1080/15295036.2016.1193670.

- Cullerton, K., Donnet, T., Lee, A., & Gallegos, D. (2016). Exploring power and influence in nutrition policy in Australia. Obesity Reviews, 17(12), 1218–1225 doi:10.1111/obr.12459.

- da Costa Louzada, M. L., Levy, R. B., Martins, A. P. B., Claro, R. M., Steele, E. M., Verly Jr, E., Cafiero, C., & Monteiro, C. A. (2017). Validating the usage of household food acquisition surveys to assess the consumption of ultra-processed foods: Evidence from Brazil. Food Policy, 72(September), 112–120. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.08.017.

- De Cock, L., Dessein, J., & de Krom, M. P. (2016). Understanding the development of organic agriculture in Flanders (Belgium): A discourse analytical approach. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 79(1), 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2016.04.002.

- de Solier, I. (2018). Tasting the digital: New food media. In K. LeBesco & P. Naccarato (Eds.), The bloomsbury handbook of food and popular culture (pp. 54–65). Bloomsbury.

- Eicher-miller, H. A., Fulgoni, V. L., & Keast, D. R. (2012). Contributions of processed foods to dietary intake in the US from 2003–2008: A report of the food and nutrition science solutions joint task force of the academy of nutrition and dietetics, American Society for Nutrition, institute of food technologists, and international food information council. Journal of Nutrition, 142(11), 2065S–2072S. doi:10.3945/jn.112.164442.

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

- Fiolet, T., Srour, B., Sellem, L., Kesse-Guyot, E., Allès, B., Méjean, C., Deschasaux, M., Fassier, P., Latino-Martel, P., Beslay, M., Hercberg, S., Lavalette, C., Monteiro, C. A., Julia, C., & Touvier, M. (2018). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ, 360(8141). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k322

- Fraanje, W., & Garnett, T. (2019). What is ultra-processed food? And why do people disagree about its utility as a concept?. Foodsource: buildingblocks. Food Climate Research Network, University of Oxford. doi:10.56661/ca3e86f2.

- Gibney, M. J., Forde, C. G., Mullally, D., & Gibney, E. R. (2017). Ultra-processed foods in human health: A critical appraisal. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 106(3), 717–724. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.160440

- Goodman, M. K., Johnston, J., & Cairns, K. (2017). Food, media and space: The mediated biopolitics of eating. Geoforum, 84, 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.017.

- Huebbe, P., & Rimbach, G. (2020). Historical reflection of food processing and the role of legumes as part of a healthy balanced diet. Foods, 9(8), 1–16. doi:10.3390/foods9081056.

- IFIC. (2010). Understanding our food communications tool kit. https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/IFIC_Leader_Guide_high_res.pdf

- Inghelbrecht, L., Dessein, J., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2014). The non-GM crop regime in the EU: How do industries deal with this wicked problem? NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 70-71(1), 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2014.02.002.

- Jones, J. M. (2019). Food processing: Criteria for dietary guidance and public health? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 78(1), 4–18. doi:10.1017/S0029665118002513.

- Krause, A., & Bucy, E. P. (2018). Interpreting images of fracking : How visual frames and standing attitudes shape perceptions of environmental risk and economic benefit. Environmental Communication, 12(3), 322–343. doi:10.1080/17524032.2017.1412996.

- Kuttschreuter, M., Gutteling, J. M., & de Hond, M. (2011). Framing and tone-of-voice of disaster media coverage: The aftermath of the Enschede fireworks disaster in the Netherlands. Health, Risk and Society, 13(3), 201–220. doi:10.1080/13698575.2011.558620.

- Kwak, E. J., & Grable, J. E. (2021). Conceptualizing the use of the term financial risk by non-academics and academics using twitter messages and ScienceDirect paper abstracts. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 11(1), 1–14. doi:10.1007/s13278-020-00709-9.

- Lappeman, J., Clark, R., Evans, J., Sierra-Rubia, L., & Gordon, P. (2020). Studying social media sentiment using human validated analysis. MethodsX, 7(100867), 100867. doi:10.1016/j.mex.2020.100867.

- Lewis, T. (2018). Digital food: From paddock to platform. Communication Research and Practice, 4(3), 212–228. doi:10.1080/22041451.2018.1476795.

- Lilleker, D. G., Veneti, A., & Jackson, D. (2019). Introduction: Visual political communication. In A. Veneti, D. Jackson, & D. G. Lilleker (Eds.), Visual political communication (pp. 1–13). Palgrave Macmillan.

- List of countries by English-speaking population. (n.d.). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_English-speaking_population

- Lupton, D. (2018). Cooking, eating, uploading: Digital food cultures. In K. LeBesco & P. Naccarato (Eds.), The bloomsbury handbook of food and popular culture (pp. 66–79). Bloomsbury.

- Lupton, D. (2020). Understanding digital food cultures. In D. Lupton & Z. Feldman (Eds.), Digital food cultures (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- Marks, L. A., Kalaitzandonakes, N., Wilkins, L., & Zakharova, L. (2007). Mass media framing of biotechnology news. Public Understanding of Science, 16(2), 183–203. doi:10.1177/0963662506065054.

- Marres, N. (2017). Digital sociology: The reinvention of social research. Polity. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Marres, N., & Rogers, R. (2005). Recipe for tracing issues and their publics on the web. In B. Latour & P. Weibel (Eds.), Making things public: Atmospheres of democracy (pp. 922–935). ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe and MIT Press.

- Marrón-Ponce, J. A., Flores, M., Cediel, G., Monteiro, C. A., & Batis, C. (2019). Associations between consumption of ultra-processed foods and intake of nutrients related to chronic non-communicable diseases in mexico. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(11), 1852–1865. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2019.04.020.

- Martínez Steele, E., Juul, F., Neri, D., Rauber, F., & Monteiro, C. A. (2019). Dietary share of ultra-processed foods and metabolic syndrome in the US adult population. Preventive Medicine, 125(May), 40–48. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.05.004.

- Metze, T. (2018). Visual framing for policy learning: Internet as the eye of the public. In Dotti (Ed.), Knowledge, policymaking and learning for European cities and regions: From research to practice. Edwar Elgar Publishing 165–180.

- Metze, T. (2020). Visualization in environmental policy and planning: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 22(5), 745–760. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1798751.

- Monteiro, C., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936–941. doi:10.1017/S1368980018003762.

- Morseletto, P. (2017). Analysing the influence of visualisations in global environmental governance. Environmental Science and Policy, 78(August), 40–48. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.08.021.

- Nisbet, M., & Huge, M. (2007). Where do science debates come from? Understanding attention cycles and framing. In Brossard, Dominique Shanahan James, (Eds.), The media, the public and agricultural biotechnology (pp. 193–230). CAB Internationa. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845932046.0193

- Nisbet, M., & Lewenstein, B. (2002). Biotechnology and the American media: The policy process and the elite press, 1970 to 1999. Science Communication, 23(4), 359–391. doi:10.1177/107554700202300401.

- O’Neill, S. J October . (2013). Image matters: Climate change imagery in US, UK and Australian newspapers. Geoforum, 49, 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.030.

- Oleschuk, M. (2020). “in Today’s Market, Your Food Chooses You”: News media constructions of responsibility for health through home cooking. Social Problems, 67(1), 1–19. doi:10.1093/socpro/spz006.

- Perini, L. (2005). Visual representations and confirmation. Philosophy of Science, 72(5), 913–926. doi:10.1086/508949.

- Poti, J. M., Mendez, M. A., Ng, S. W., & Popkin, B. M. (2015). Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by US households? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 101(6), 1251–1262. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.100925.

- Redden, J. (2011). Poverty in the news: A framing analysis of coverage in Canada and the UK. Information Communication and Society, 14(6), 820–849. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.586432.

- Richter, D. H. (1998). Saussure, ferdinand. “Nature of the linguistic sign. In D. H. Richter (Ed.), The critical tradition: Classic texts and contemporary trends (pp. 832–835). Bedford/St. Martin’s Press.

- Rodriguez, L., & Dimitrova, D. V. (2011). The levels of visual framing. Journal of Visual Literacy, 30(1), 48–65. doi:10.1080/23796529.2011.11674684.

- Rogers, R. (2019). Doing digital methods. Sage Publications.

- Rojas-Padilla, E., Metze, T., & Termeer, K. (2022). Seeing the visual: A literature review on why and how policy scholars would do well to study influential visualizations. Policy Studies Yearbook, 12(1), 103–136. doi:10.18278/psy.12.1.5.

- Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (4th ed.). Sage.

- Rousseau, S. (2012). Food and social media: You are what you tweet. AltaMira Press.

- Schneider, T., Eli, K., Dolan, C., & Ulijaszek, S. (2018). Introduction: Digital food activism - food transparency one byte/bite at a time? In Schneider, T., Eli, K., Dolan, C., Ulijaszek, S. (Eds.), Digital food activism (pp. 1–24). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315109930_1

- Schwarz, E. A. G. (2013). Visualizing the Chesapeake bay watershed debate. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 7(2), 169–190. doi:10.1080/17524032.2013.781516.

- Steele, M., Euridice, P., M, B., Swinburn, B., & Monteiro, C. A. (2017). The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Population Health Metrics, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-017-0119-3

- Vaast, E., Davidson, E. J., & Mattson, T. (2013). Talking about technology: The emergence of a new actor category through new media. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1069–1092. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43825782.

- van Beek, L., Metze, T., Kunseler, E., Huitzing, H., de Blois, F., & Wardekker, A. (2020). Environmental visualizations: Framing and reframing between science, policy and society. Environmental Science & Policy.

- Wozniak, A., Wessler, H., & Lück, J. (2017). Who prevails in the visual framing contest about the united nations climate change conferences? Journalism Studies, 18(11), 1433–1452. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2015.1131129.

- Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis. Sage Publications.

- Yigitcanlar, T., Kankanamge, N., Regona, M., Maldonado, A. R., Rowan, B., Ryu, A., Desouza, K. C., Corchado, J. M., Mehmood, R., & Li, R. Y. M. (2020). Artificial intelligence technologies and related urban planning and development concepts: How are they perceived and utilized in Australia? Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 1–21. doi:10.3390/joitmc6040187.