Abstract

Objective

To investigate the associations between demographic factors, binge drinking, psychological distress, psychological flexibility, and self‐reported Days Out of Role (DOR) among students attending a large metropolitan university in Sydney, Australia. This study aimed to determine whether psychological flexibility moderated the association between psychological distress and DOR.

Method

All enrolled students were invited to participate in an online survey titled ‘The Mental Health Census’ which contained standardised measures of binge drinking, psychological distress, and psychological flexibility. Students received an email, which outlined the purpose of the study, including the link to the anonymous survey.

Results

A total of 3950 students participated in the survey. A higher number of DOR was significantly associated with a Non‐English Speaking Language (NESL) background, binge drinking and economic hardship. Greater DOR was also associated with increased psychological distress and lower levels of psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility was found to moderate the association between psychological distress and DOR: students experiencing high distress were less likely to report greater DOR if they possessed higher levels of psychological flexibility.

Conclusions

Overall, this study confirmed that university students experiencing psychological distress are at a greater risk of experiencing DOR, which may be counteracted by improving psychological flexibility.

Participating in university education is a common pathway for both young people exiting high school (OECD, Citation2013), and mature age students re‐entering the education system (Gale & Parker, Citation2013). Higher education plays a vital role in the economic, cultural, and social development of communities. Attending university has become more accessible, with an estimated one million people currently enrolled in Australian universities (Gale & Parker, Citation2013). The individual and societal benefits of tertiary education include: economic gains (Feinstein & Hammond, Citation2004; Vila, Citation2005); lower unemployment rates (Baum, Ma, & Payea, Citation2013); a greater likelihood of adopting healthier lifestyle choices (Baum et al., Citation2013); enhanced civic and community participation (Feinstein & Hammond, Citation2004); increased social capital (Hammond, Citation2002); and greater opportunities to acquire cognitive, emotional, and creative competencies (Nussbaum, Citation2012). Given these benefits, maintaining student participation in university study is paramount.

Educational opportunity and student functioning, however, can be compromised by a range of challenges, including: financial strain (Cvetkovski, Reavley, & Jorm, Citation2012; Halliday‐Wynes & Nguyen, Citation2014), stress associated with study commitments and workloads (Cvetkovski et al., Citation2012; Kausar, Citation2010), sleep disturbances (Buboltz, Brown, & Soper, Citation2001), and the competitive pressure to succeed (Andrews & Chong, Citation2011; Tavolacci et al., Citation2013). This can lead to an overall increase in psychological distress: the general concept of maladaptive psychological functioning in the face of stressful life events (Ridner, Citation2004). University students have been found to experience greater rates of moderate (Cvetkovski et al., Citation2012) and high (Leahy et al., Citation2010; Stallman, Citation2010) psychological distress when compared with their age‐matched community peers. This distress can adversely impact student engagement (Dahlin, Nilsson, Stotzer, & Runeson, Citation2011), contribute to diminished academic performance (Akgun & Ciarrochi, Citation2003) and lower degree completion rates (Kessler, Foster, Saunders, & Stang, Citation1995; Lee et al., Citation2009). By measuring the disengagement that results from students' distress, university services are better placed to assist students. One such measure is Days Out of Role (DOR).

DOR is the number of days in which a student reports a total inability to meet their work, study, and day‐to‐day commitments. It has been found to be positively associated with greater psychological distress in both university students (Stallman, Citation2010) and general samples (Hilton, Sheridan, Cleary, & Whiteford, Citation2009; Holden et al., Citation2011). DOR presents a unique challenge for university students as it compounds the difficulties they face in completing work to set deadlines, thereby increasing academic pressure and exacerbating their symptoms of distress (Stallman, Citation2010). According to Andrews, Hall, Teesson, and Henderson (Citation1999), DOR for university students with mental illness is considerable: Students with anxiety disorders have been found to report up to six DOR during a 12‐week semester while students with mood disorders reported nine DOR. Students under 25 years may be more likely to experience DOR as up to 75% of mental health and substance use disorders emerge before this age (Kessler et al., Citation2005). Given the range of emotional and financial support structures that exist within the higher education context, universities are well placed to minimise the impact of psychological distress on DOR. However, the size of student populations often means that services are stretched (Stallman, Citation2012) and not all students impacted will seek help (Blanco et al., Citation2008; Hunt & Eisenberg, Citation2010; Verger, Guagliardo, Gilbert, Rouillon, & Kovess‐Masfety, Citation2010), limiting the effectiveness of such support structures. To improve university services, targeted approaches are needed; however, this requires a better understanding of the range of factors that may place students at risk of experiencing DOR.

Little is known about the risk factors associated with increased DOR in the university setting. In general populations, risk factors include gender (females are more likely to report greater DOR; Korten & Henderson, Citation2000); older age (Rickwood, Telford, Parker, Tanti, & McGorry, Citation2014); mental health problems, in particular depression (Merikangas et al., Citation2007), panic, post‐traumatic stress, and bipolar disorder (Alsonso et al., Citation2011); substance use disorders (Andrade et al., Citation2013; Holden et al., Citation2011); financial stress (Kim, Sorhaindo, & Garman, Citation2006); and workplaces where employees have high demands but low control (Roelen, Weites, Koopmans, van der Klink, & Groothoff, Citation2008). Within the higher education setting, student background factors may impact DOR (Grebennikov & Skaines, Citation2008), but this is yet to be confirmed. Behavioural risk factors such as binge drinking may also be relevant, as higher rates have been reported among university students (Rimsza & Moses, Citation2005). Binge drinking is both a serious health and social issue as it is often accompanied by educational and psychosocial difficulties, antisocial behaviours, overdoses, and risk‐taking behaviours, such as alcohol‐impaired driving and higher‐risk sexual activity (Wechsler et al., Citation2002). Understanding the impact of such behaviour on DOR is important for improving the well‐being of students.

Research on protective factors for DOR is unclear. The construct of psychological flexibility has emerged as a plausible factor (Bond et al., Citation2011). Psychological flexibility refers to the effectiveness with which a person adapts to their changing demands and shifts their mental resources and perspectives, whilst managing competing needs, wants, and lifestyle demands (Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010). Involving mindful self‐awareness of ones' thoughts and feelings, and acting in ways consistent with ones' values (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, Citation1999), greater psychological flexibility has been linked to perceived quality of life and affective well‐being (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, Citation2006). Importantly, greater psychological flexibility does not preclude an individual from experiencing mental health symptoms, but instead, improves their versatility and ability to navigate the challenges they face (Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010). Psychological flexibility has not been found to be associated with age, gender, or race (Bond et al., Citation2011). Understanding the relationship between psychological distress and psychological flexibility may help psychological services to create targeted interventions aimed at preventing DOR.

The current study aimed to explore the associations between self‐reported demographic, behavioural, and psychological risk factors and DOR among university students. It was hypothesised that psychological flexibility would moderate the association between psychological distress and DOR: At high levels of psychological flexibility, psychological distress would be associated with less DOR than at low levels of psychological flexibility. Overall, this study aims to assist university services in designing targeted prevention strategies.

Method

Sample and procedure

In the first semester of the academic year of 2012 (2–6 April), all enrolled students (N = 50,206) attending a large metropolitan university in Sydney, Australia, were invited to participate in an online survey titled ‘The Mental Health Census'. Recruitment was conducted after the Higher Education Contribution Scheme census date to control for withdrawing students. Students received an email, which outlined the purpose of the study, including the link to the anonymous survey. A total of 4,125 students consented to participate. Of the consenting participants, 4% (n = 159) chose not to continue the survey. Students were excluded if they did not indicate their gender (n = 16). The final sample consisted of 3,950 participants. This represented 8% of the total student population at the time of the survey. Ethics was granted by the participating university's Human Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

Demographics

Single questions assessed participants' gender and age. Age was dichotomised to explore the vulnerability of those between 16 and 25 years specifically. Relationship status: Participants indicated whether they were (1) single, divorced, separated, widowed, or (2) partnered or married. Language background: (1) English language, (2) Non‐English Speaking Language (NESL). First person in their family to attend university: (1) no, (2) yes. Level of study: (1) undergraduate, (2) postgraduate. Student type: (1) domestic, (2) international. Attendance: (1) full‐time, (2) part‐time. Living arrangement: Participants indicated whether they were living with (1) family or partner, (2) university accommodation, (3) non‐university shared accommodation, or (4) living alone. Travel time: Using dichotomous categories, participants indicated how much time they spent travelling one‐way from place of residence to university: (1) ≤90 minutes, (2) >90 minutes. Economic hardship: Participants were asked to select which statement best described their financial situation: (1) I am often unable to pay for rent, food, and study materials, (2) I am usually able to pay for rent, food, and study materials but not much else, (3) I am comfortably able to pay for rent, food, and study materials. Participants who reported they were often unable to pay for rent, food, and study materials were classified as experiencing economic hardship. History of mental health issue: Participants were asked whether they have ever been diagnosed with, or treated for, a mental health issue: (1) no, (2) yes.

Binge drinking

Using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT‐C; Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, Citation1998), participants who reported consuming six or more standard drinks on one occasion either weekly or daily/almost daily (i.e. scored ≥3 on question three) were classified as binge drinkers.

Psychological factors

Psychological distress (PD): This was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., Citation2003). This scale was used to measure how frequently participants experienced symptoms of non‐specific psychological distress, incorporating symptoms linked to anxiety and depression (Poulin, Lemoine, Leo‐Roch, & Lambert, Citation2005). Participants were asked to indicate how often, in the past 30 days, they had experienced the 10 items which corresponded to an expression of distress: pessimism towards the future, anguish and stress, self‐depreciation, social withdrawal, and somatisation (Masseé, Citation2000). This scale also incorporates symptoms that are linked to depression and anxiety (Poulin et al., Citation2005). Responses were given using a five‐category scale ranging from ‘all of the time' (5) to ‘none of the time' (1). The items are summed to give overall scores ranging from 10 to 50, with a higher score indicating higher levels of distress. Scores above 30 indicate a severe level of psychological distress and the likelihood of mental health disorder. This scale has high internal consistency in adult populations (Cronbach's α = .93; Kessler et al., Citation2003). Psychological flexibility (PF): Using the revised seven‐item Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ‐II; Bond et al., Citation2011), participants rated their ability or willingness to remain in contact with painful and negative events on a 7‐point likert scale ranging from ‘never true’ (1) to ‘always true’ (7). Sample items include ‘I'm afraid of my feelings’ and ‘Emotions cause problems in my life’. All items are summed to give a final total (range 7–49), with a lower score indicating greater psychological flexibility. The scale has been validated in university samples (Bond et al., Citation2011) and has demonstrated internal consistency (mean α = .84) and discriminant validity (Bond et al., Citation2011).

Days Out of Role (DOR)

Participants were asked to report the number of days, in the past month, that they were completely unable to work, study, or manage daily activities specifically because of their psychological distress. Where participants reported a range of days, the average was calculated. This single question, which is based on a series of four questions about work loss days compiled for the US National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler & Frank, Citation1997), has been used in other Australian university‐based research (Stallman, Citation2010; Stallman & Shochet, Citation2009) and in research with young adults with emerging mental health issues (Rickwood et al., Citation2014).

Analysis

This study utilised cross‐sectional survey data from a university‐wide Mental Health Census. All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS Version 22. In order to investigate response bias, a missing data analyses was conducted to determine whether participants who did not answer the question relating to DOR were significantly different from those who did: Group differences were explored using t‐tests and simple binary logistic regressions for categorical variables. Gender differences were likewise assessed. All analyses used centred scores for psychological distress and psychological flexibility to control for collinearity between these two (Aiken & West, Citation1991). The interaction term for psychological flexibility and psychological distress was calculated using the centred scores. To explore the simple bivariate associations for DOR, listwise Pearson product moment correlations (continuous variables) and Point‐biserial correlations (dichotomous categorical variables) were conducted. To display all of the bivariate associations in a single table, Spearman's rank order correlation coefficients were reported for the analyses that examined the relationship between two categorical variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). Due to the number of bivariate tests conducted (n = 15), an adjusted alpha value using a Bonferroni correction was used: For interpretation purposes, only associations with p < .003 were discussed. However, given the exploratory nature of the study, the multivariate analyses cautiously included all variables that demonstrated bivariate significance at p < .05. To control for the relationships between variables, a multivariate hierarchical linear regression analyses was conducted using four models: DOR was entered as the continuous dependent variable. Given the non‐modifiable nature of some demographics, these were entered into the first sequence alongside binge drinking. To explore the main associations for psychological distress and psychological flexibility, these were entered separately in Models 2 and 3. As understanding the interaction between psychological distress and flexibility was a primary aim of the study, the interaction term for psychological distress and psychological flexibility was then entered on its own in the last model. Collinearity diagnostics for the regression analyses did not violate the assumptions of tolerance or the variation inflation factor (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007).

Results

Participants

In this sample (N = 3,950, M: 24.16 years, standard deviation (SD): 8.0, age range: 16–74 years, 71% female), 82% (n = 3,235) attended university full‐time, 85% (n = 3,374) were domestic students, and 68% (n = 2,692) were undergraduates. Of undergraduates, 83% were aged between 16 and 25 years. A total of 23% (n = 903) were the first person in their family to attend university, 45% (n = 1,795) of the sample were in a partnered relationship, 77% (n = 3,035) came from an English speaking background, 8% (n = 327) travelled for more than 90 minutes to attend university, and 13% (n = 518) experienced economic hardship. Overall, 66% (n = 2,618) were living with their family or partner, 7% (n = 260) were living in university accommodation, 22% (n = 858) were living in other accommodation, and 5% (n = 214) were living alone. A total of 9% (n = 347) were classified as binge drinkers. Within the current sample, 27% (n = 1,051) had previously been diagnosed with, or treated for, a mental health issue. Participants reported a mean psychological distress score of 22.83 (SD: 8.00, Cronbach's α: .92), with 20% (n = 791) reporting severe distress levels; the mean score for psychological flexibility was 21.53 (SD: 10.20, Cronbach's α: .93).

Response bias

Participants who did not answer the question for DOR (n = 324) had lower levels of psychological distress [t (189.72) = –6.09, p < .001] and greater psychological flexibility [t (205.07) = –5.11, p < .001] than those who did. Non‐responders were more likely to be from an NESL background (OR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.07–1.78, p < .05), an international student (OR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.08–1.94, p < .05), of postgraduate study level (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.05–1.67, p < .05). No other significant differences were found.

Gender differences

Females in the current study were significantly more likely to be in a partnered relationship (OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.16–1.54, p < .001), have a history of mental illness (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.34–1.87, p < .001), and report a higher level of psychological distress (females: 23.41, SD: 7.78 vs males: 22.25, SD: 7.87, t (3,495) = –3.95, p < .001) than males. In contrast, males were more likely to be aged above 26 years (OR: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.18–1.60, p < .001), from an NESL background (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.15–1.58, p < .001), an international student (OR: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.25–1.81, p < .001), and report a higher level of psychological flexibility (males: 20.47, SD: 10.14, vs female: 22.23, SD: 10.08). Males were also more likely to be binge drinkers than females (OR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.61–2.53, p < .001). No other gender differences were found.

Primary analyses

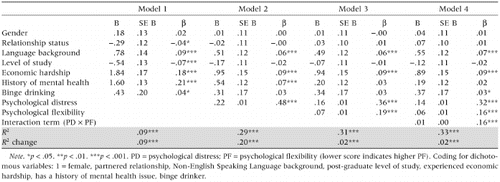

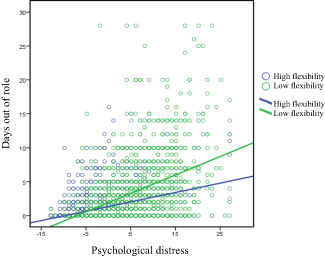

Overall, 43% of students (n = 1,556/3,639) reported one or more DOR in the previous month (M: 1.9, SD: 3.5, range: 0‐28). As outlined in Table , greater DOR was significantly associated with higher levels of psychological distress and lower levels of psychological flexibility. Greater DOR was also associated with those who were not in partnered relationships, those from an NESL background, those of an undergraduate study level, economic hardship, and a history of mental illness. No other significant associations were found. In the multivariate analyses (Table ), greater DOR was found to be significantly and independently associated with NESL background, economic hardship, binge drinking, greater psychological distress, and poorer psychological flexibility. Model 1 (including demographics and binge drinking) was only associated with 9% of the variance in DOR. The addition of the psychological measures accounted for the greatest change in R2. The final model was associated with 33% of the variance in DOR. The interaction term for psychological distress and psychological flexibility was significant, indicating that greater flexibility resulted in fewer DOR for those experiencing higher distress. The strength of the interaction was small (see Fig. 1).

Table 1. Bivariate correlations (n = 3,484)

Discussion

In this sample of university students, 43% reported taking one or more days out of role in the previous month. The prevalence of DOR in this sample is considerably higher than that reported by the general population of Australians in which only 22% report DOR in the previous month (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2010). Furthermore, the psychological distress levels of the students in this study aged 16–25 years were higher than that found in the general population of Australian young adults (Slade, Grove, & Burgess, Citation2011). This is consistent with the notion that the university environment is psychologically distressing for many young people, and that increased levels of distress are associated with higher DOR (Stallman, Citation2010).

Overall, DOR was significantly associated with relationship status, language background, level of study, economic hardship, and history of mental health issue in addition to psychological distress and psychological flexibility. The multivariate analyses revealed that students who were from NESL background, reported economic hardship, engaged in binge drinking, and reported high psychological distress and low psychological flexibility were at greatest risk of experiencing DOR. While the association between economic hardship and DOR is not surprising (Kim et al., Citation2006), it provides evidence that students reporting higher DOR are also vulnerable to experiencing financial strain. This may be a direct outcome of their impaired functioning or alternatively a cause of it. As this was a cross‐sectional study, causality cannot be inferred. In addition, the association between NESL and DOR may not be surprising. Students with NESL backgrounds often face unique challenges in the university environment, including communication difficulties (Mulligan & Kirkpatrick, Citation2000), an awareness of ‘differentness’ (Rigali‐Oiler & Robinson Kurpius, Citation2013), and cultural barriers that may increase their DOR resulting from distress. Importantly, binge drinkers appear to be at a greater risk of DOR, in line with previous research showing that binge drinking is associated with poor academic performance and missed classes (Presley & Pimentel, Citation2006). As alcohol is often used as coping mechanism, understanding the relationship between distress and alcohol intake among university students is crucial to minimising DOR. Combined, these factors may assist university services in targeting their approaches for decreasing DOR among students.

Consistent with our hypothesis, the interaction term for psychological distress and psychological flexibility was significant: Students who experienced higher psychological distress, but possessed greater psychological flexibility, reported fewer DOR. This supports the notion that psychological flexibility is a protective factor and one that can be fostered and strengthened within the university environment. Psychological counselling, in particular, can help students improve psychological flexibility by helping to develop specific coping skills for managing distress (Conley, Travers, & Bryant, Citation2013; Julal, Citation2013; Shapiro, Brown, & Astin, Citation2011). Specifically, emotion regulation strategies (Kashdan, Barrios, Forsyth, & Steger, Citation2006), such as cognitive reappraisal (Flaxman & Bond, Citation2010) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy interventions (Lloyd, Bond, & Flaxman, Citation2013; Renner & Foley, Citation2013) have been found to be effective for improving psychological flexibility and minimising psychological distress in the face of adversity. However, it must be noted that the size of the association found was small. Future experimental methods would help to better understand this relationship.

Limitations of the study

Due to the nature of the study design, directions of causality cannot be determined. Longitudinal follow‐up of students will help determine the causal factors for DOR. In addition, including academic outcomes and other aspects of social and occupational functioning, such as employment, would also assist to better understand those at risk of DOR. Although the gender difference in average DOR was not convincing, the response rate and lack of male participation in the survey limits the generalisability of results. Although university populations in Australia commonly have higher participation rates among females (Australian Government, Citation2013; University of Sydney, Citation2012), investigating gender differences is important, given that males experience greater levels of stigma (Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein, & Zivin, Citation2009) and are less likely to seek help when experiencing distress (Mojtabai, Citation2007). Furthermore, gender may moderate the associations of some measures such as binge drinking, as males in the current study reported higher levels of binge drinking compared with females. To test such hypotheses and control for the response bias, future studies need to incorporate a more diverse response from the student body, particularly from males. There are a number of other factors that may also be related to DOR which were not investigated by the current study. These include, but are not limited to, physical injury or sickness (Merikangas et al., Citation2007), insomnia (Hajak et al., Citation2011), family or caring responsibilities, employment roles (Roelen et al., Citation2008), and other social or religious commitments.

Concluding remarks

Given reports of the high level of distress in university samples (Leahy et al., Citation2010; Stallman, Citation2010), students are at risk of experiencing DOR (Stallman, Citation2010). From a student success perspective, in addition to providing financial and study supports (Kuh, Kinzie, Buckley, Bridges, & Hayek, Citation2007), future interventions should move towards targeted approaches which take into account students' backgrounds and social behaviour, for example, assisting NESL students and addressing binge drinking. At the individual level, results of this study indicate that having increased psychological flexibility may attenuate the impact of distress on students' ability to remain effectively engaged with their studies. Although university is a high‐stress environment for many students, it also provides access to beneficial psycho‐social services, such as counselling, employment/careers, housing, and financial support that can be utilised to improve student functioning in a demanding, high‐performance environment. In turn, such educational investment in developing student competencies may boost human capital accumulation and contribute to national well‐being.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with thanks Dr Chien Hoong Gooi and Eileen Seah for their assistance in conducting The Mental Health Census and statistical preparation of the data.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Akgun, S., & Ciarrochi, J. (2003). Leaned resourcefulness moderates the relationship between academic stress and academic performance. Educational Psychology, 23, 287–294.

- Alsonso, J., Petukhova, M., Vilagut, G., Chatterji, S., Heeringa, S., Ustun, T. B., … Kessler, R. C. (2011). Days out of role due to common physical and mental conditions: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Molecular Psychiatry, 16, 1234–1246.

- Andrade, L. H., Baptista, M. C., Alonso, J., Petukhova, M., Bruffaerts, R., Kessler, R. C., … Viana, M. C. (2013). Days out‐of‐role due to common physical and mental health problems: Results from the Sao Paulo Megacity Mental health survey, Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 68(11), 1392–1399.

- Andrews, A., & Chong, J. L. Y. (2011). Exploring the wellbeing of students studying at an Australian university. Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Student Services Association, 37, 9–37.

- Andrews, G., Hall, W., Teesson, M., & Henderson, S. (1999). The Mental Health of Australians (2). Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services.

- Australian Government. (2013). Selected higher education statistics—2013 student data. Retrieved July 10, 2014, from http://www.education.gov.au/selected‐higher‐education‐statistics‐2013‐student‐data

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2010). Australia's health 2010. Australia's health series no. 12. Canberra: AIHW. Cat. no. AUS 122.

- Baum, S., Ma, J., & Payea, K. (2013). Education pays 2013: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. Retrieved January, 2013 from https://trends.collegeboard.org/education‐pays

- Blanco, C., Okuda, M., Wright, C., Hasin, D. S., Grant, B. F., Shang‐min liu, M. S., & Hasin, D. S. (2008). Mental health of college students and their non‐college‐attending peers: Results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 1429–1437.

- Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., … Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire‐II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42, 676–688.

- Buboltz, W. C., Brown, F., & Soper, B. (2001). Sleep habits and patterns of college students: A preliminary study. Journal of American College Health, 50(3), 131–135.

- Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., Mcdonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questionnaire (AUDIT‐C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1789–1795. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

- Conley, C. S., Travers, L. V., & Bryant, F. B. (2013). Promoting psychosocial adjustment and stress management in first‐year college students: The benefits of engagement in a psychosocial wellness seminar. Journal of American College Health, 61, 75–86.

- Cvetkovski, S., Reavley, N. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2012). The prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in Australian tertiary students compared to their community peers. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46, 457–467.

- Dahlin, M., Nilsson, C., Stotzer, E., & Runeson, B. (2011). Mental distress, alcohol use and help‐seeking among medical and business students: A cross‐sectional comparative study. Medical Education, 11, 92–99.

- Eisenberg, D., Downs, M., Golberstein, E., & Zivin, K. (2009). Stigma and help‐seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review, 66, 522–541.

- Feinstein, L., & Hammond, C. (2004). The contribution of adult learning to health and social capital. Oxford Review of Education, 30(2), 199–221.

- Flaxman, P. E., & Bond, F. W. (2010). A randomised worksite comparison of acceptance and commitment therapy and stress inoculation training. Behavior Research and Therapy, 48, 816–820. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.004

- Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2013). Widening participation in Australian higher education. Report to the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) and the Office of Fair Access (OFFA) England, CFE (Research and Consulting) Ltd, Leicester, UK and Edge Hill University, Lancashire, UK.

- Grebennikov, L., & Skaines, I. (2008). University of Western Sydney students at risk: Profile and opportunities for change. Journal of Institutional Research, 14, 58–70.

- Hajak, G., Petukhova, M., Lakoma, M. D., Coulouvrat, C., Roth, T., Sampson, N. A., … Kessler, R. C. (2011). Days‐out‐of‐role associated with insomnia and comorbid conditions in the America Insomnia Survey. Biological Psychiatry, 70, 1063–1073.

- Halliday‐wynes, S., & Nguyen, N. (2014). Does financial stress impact on young people in tertiary study? Adelaide: NCVER.

- Hammond, C. (2002). What is it about education that makes us healthy? Exploring the education‐health connection. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21, 551–571.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experimental approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44, 1–25.

- Hilton, M. F., Sheridan, J., Cleary, C. M., & Whiteford, H. A. (2009). Employee absenteeism measures reflecting current work practices may be instrumental in a re‐evaluation of the relationship between psychological distress/mental health and absenteeism. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 18, 37–47.

- Holden, L., Scuffham, P. A., Hilton, M. F., Ware, R. S., Vecchio, N., & Whiteford, H. A. (2011). Which health conditions impact on productivity in working Australians? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53(3), 253–257.

- Hunt, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Mental health problems and help‐seeking behavior among college students. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 46, 3–10.

- Julal, F. S. (2013). Use of student support services among university students: Associations with problem‐focused coping, experience of personal difficulty and psychological distress. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41, 414–425.

- Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 865–878.

- Kashdan, T. B., Barrios, V., Forsyth, J. P., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behavior Research and Therapy, 9, 1301–1320.

- Kausar, R. (2010). Perceived stress, academic workloads and use of coping strategies by university students. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 20(1), 31–46.

- Kessler, R. C., & Frank, R. G. (1997). The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychological Medicine, 27, 861–873.

- Kessler, R. C., Foster, C. L., Saunders, W. B., & Stang, P. E. (1995). Social consequences of psychiatric disorders. I: Educational attainment. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(7), 1026–1032.

- Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, B. A., Hiripi, E., … Zaslavsky, A. M. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 184–189.

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age‐of‐onset distributions of DSM–IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

- Kim, J., Sorhaindo, B., & Garman, E. T. (2006). Relationship between financial stress and workplace absenteeism of credit counselling clients. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 27, 458–478.

- Korten, A., & Henderson, S. (2000). The Australian National Survey Of Mental Health And Well‐Being: Common psychological symptoms and disablement. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 325–330.

- Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J., Bridges, B., & Hayek, J. (2007). Piecing together the student success puzzle: Research, propositions, and recommendations. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass. Association for the Study of Higher Education (ASHE) Higher Education Report, 32(5).

- Leahy, C. M., Peterson, R. F., Wilson, I. G., Newbury, J. W., Tonkin, A. L., & Turnbull, D. (2010). Distress levels and self‐reported treatment rates for medicine, law, psychology and mechanical engineering tertiary students: Cross‐sectional study. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44, 608–615.

- Lee, S., Tsang, A., Breslau, J., Aquilar‐gaxiola, S., Angermeyer, M., Borges, G., … Kessler, R. C. (2009). Mental disorders and termination of education in high‐income and low‐ and middle‐income countries: Epidemiological study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194, 411–417.

- Lloyd, J., Bond, F., & Flaxman, P. E. (2013). The value of psychological flexibility: Examining psychological mechanisms underpinning a cognitive behavioural therapy intervention for burnout. Work and Stress, 27, 181–199.

- Masseé, R. (2000). Qualitative and quantitative analyses of psychological distress: Methodological complementarity and ontological incommensurability. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 411–423.

- Merikangas, K. R., Ames, M., Cui, L., Stang, P. E., Bedirhan, T., Von korff, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The impact of cormorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1180–1188.

- Mojtabai, R. (2007). American's attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking: 1990–2003. Psychiatry Services, 58, 642–665.

- Mulligan, D., & Kirkpatrick, A. (2000). How much do they understand? Lectures, students and comprehension. Higher Education Research and Development, 19, 311–335.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2012). Not for profit: Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- OECD. (2013). Education at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved December, 2013, from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag‐2013‐en.

- Poulin, C., Lemoine, O., Leo‐roch, P., & Lambert, J. (2005). Validation study of a nonspecific psychological distress scale. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40, 1019–1024. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127‐005‐0961‐7

- Presley, C. A., & Pimentel, E. R. (2006). The introduction of the heavy and frequent drinker: A proposed classification to increase accuracy of alcohol assessments in postsecondary educational settings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 324–331.

- Renner, P., & Foley, E. (2013). Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MCBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) at a college counseling service. In J. Pistorello (Ed.), Mindfulness and acceptance for counseling college students: Theory and practical applications for intervention, prevention and outreach (pp. 95–118). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publication.

- Rickwood, D. J., Telford, N. R., Parker, A. G., Tanti, C. J., & Mcgorry, P. D. (2014). Headspace—Australia's innovation in youth mental health: Who are the clients and why are they presenting? The Medical Journal of Australia, 200(2), 1–4.

- Ridner, S. H. (2004). Psychological distress: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45, 536–545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365‐2648.2003.02938.x

- Rigali‐oiler, M., & Robinson kurpius, S. (2013). Promoting academic persistence among racial/ethnic minority and European American freshman and sophomore undergraduates: Implications for college counselors. Journal of College Counseling, 16, 198–212.

- Rimsza, M. E., & Moses, K. S. (2005). Substance abuse on the college campus. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 307–319.

- Roelen, C. A. M., Weites, S. H., Koopmans, P. C., van der Klink, J. J. L., & Groothoff, J. W. (2008). Sickness absence and psychosocial work conditions: A multilevel study. Occupational Medicine, 58, 425–430.

- Shapiro, S., Brown, K. W., & Astin, J. (2011). Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research evidence. Teachers College Record, 113, 493–528.

- Slade, T., Grove, R., & Burgess, P. (2011). Kessler psychological distress scale: Normative data from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45, 308–316.

- Stallman, H. M. (2010). Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychologist, 45, 249–257.

- Stallman, H. M. (2012). University counselling services in Australia and New Zealand: Activities, changes and challenges. Australian Psychologist, 47, 249–253.

- Stallman, H. M., & Shochet, I. M. (2009). Prevalence of mental health problems in Australian university health services. Australian Psychologist, 44(2), 122–127.

- Tabachnick, G. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Experimental designs using ANOVA. Belmont, CA: Duxbury.

- Tavolacci, M. P., Ladner, J., Grigioni, S., Richrd, L., Villet, H., & Dechelotte, P. (2013). Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: A cross‐sectional study among university students in France, 2009–2011. BMC Public Health, 13, 724–731.

- University of Sydney. (2012). Total student enrolments 2012. All faculties enrolments by faculty, attendance type & gender (as at 31/03/12). Retrieved July 10, 2014, from http://sydney.edu.au/staff/planning/statistics/enrol/enrol.php?ci=3&type=fac&yr=2012.

- Verger, P., Guagliardo, V., Gilbert, F., Rouillon, F., & Kovess‐masfety, V. (2010). Psychiatric disorders in students in six French universities: 12‐month prevalence, comorbidity, impairment and help‐seeking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 189–199.

- Vila, L. (2005). The outcomes of investment in education and people's well‐being. European Journal of Education, 40(1), 3–11.

- Wechsler, H., Lee, J. E., Kuo, M., Seibring, M., Nelson, T. F., & Lee, H. (2002). Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study Surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health, 50(5), 203–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480209595713