Abstract

This review article offers an integration of acculturation, biculturalism, and intergroup relations research. Additionally, it argues that bicultural identities can be more accurately conceptualised as a third, hyphenated cultural identity (e.g., Chinese‐Australian), in addition to one's ethnic and the dominant national identity. In doing so, this article proposes that hyphenated cultural identities may be personally meaningful for many ethnic minorities and discusses the function of hyphenated cultural identification for individuals and society. Given the relevance of bicultural identification, it is argued that recognising and understanding a hyphenated cultural identity is fundamental to ethnic minorities' wellbeing, as well as improving the quality of intergroup relations in multicultural societies, such as Australia.

I consider myself bicultural (Chinese‐Australian) but I don't see myself as being exclusively Chinese or exclusively Australian; or more Chinese than Australian. I believe that the Chinese‐Australian identity is a culture in itself, with integrated customs from both the Chinese and Australian culture, thus creating a new culture.

19‐year‐old Chinese‐Australian (Chu, Citation2016)

INTRODUCTION

In the current climate of globalisation and international migration, cultural identities are becoming increasingly complex (Arnett, Citation2002; Berry, Citation2008; Morris, Chiu, & Liu, Citation2015). In many multicultural countries, like Australia, ethnic minorities are consequently beginning to identify as bicultural. Here, the concept of bicultural identity refers to the outcome of experiencing two cultures simultaneously, where the values, traditional systems, and behaviours pertaining to one's heritage culture (e.g., Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese) and the dominant national culture (e.g., Australian) are integrated within the self (Fleischmann & Verkuyten, Citation2016; Hong, Zhan, Morris, & Benet‐Martínez, Citation2016; Huynh, Nguyen, & Benet‐Martínez, Citation2011; LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, Citation1993; Nguyen & Benet‐Martínez, Citation2007; Schwartz & Unger, Citation2010).

Broadly speaking, a large proportion of Australians could be considered bicultural. In the most recent Australian census, 25% of the Australian population was born overseas, of whom 64% were born in a non‐English speaking country, with a further 19% having at least one overseas‐born parent (Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Citation2014). Of particular relevance to this review, Australians of Asian ancestry approximate 12% of the Australian population (2.4 million people) and are one of the largest non‐Anglo and non‐European populations in Australia (ABS, Citation2012). Comparable figures can be found in other multicultural countries, like New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2014) and Canada (Statistics Canada, Citation2013). Biculturalism has consequently gained currency as an important aspect of ethnic identification within the study of acculturation (e.g., Berry, Citation1997) and intergroup relations (e.g., Dovidio, Gaertner, & Saguy, Citation2009; Verkuyten, Citation2016). Critically, researchers are beginning to contend that bicultural identities can be conceptualised as a hyphenated cultural identity (e.g., Chinese‐Australian, Vietnamese‐Australian), in addition to ethnic and the dominant national identity (Benet‐Martínez & Haritatos, Citation2005; Chu, Citation2016; Fine & Sirin, Citation2007; Fleischmann & Verkuyten, Citation2016; Simon & Ruhs, Citation2008). As highlighted by the anonymous participant comment above, this hyphenated cultural identity is meaningful and self‐relevant to an increasing number of ethnic minorities (van Oudenhoven, Ward, & Masgoret, Citation2006; Verkuyten, Citation2004).

This review article offers an integration of acculturation, biculturalism, and intergroup relations research. In addition, the authors review preliminary empirical work on hyphenated cultural identification amongst ethnic minorities. Second, the authors argue that ethnic minorities may have a preference that others recognise this bicultural identity. Alternatively, misrecognition of their preferred identity may have negative ramifications for intergroup relations. Recent research shows that perceived discrepancies between how minorities want to be seen, compared to how they feel they are viewed by those in the majority, have negative effects on the quality of intergroup relations (Bourhis, Moïse, Perreault, & Senecal, Citation1997), and minorities' wellbeing (Cheryan & Monin, Citation2005; Huo, Molina, Binning, & Funge, Citation2010; Huynh, Devos, & Smalarz, Citation2011; Townsend, Markus, & Bergsieker, Citation2009; Ward, Citation2009). Crucially, research on the misrecognition of ethnic minorities' bicultural identities is currently in its infancy, and this article will highlight possible implications for both the individual and society.

ACCULTURATION AND BICULTURAL IDENTITY: THEORY AND MEASUREMENT

The concept of bicultural identity is closely intertwined with acculturation (Nguyen & Benet‐Martínez, Citation2007; Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, Citation2006). In his seminal work, Berry (Citation1997) argued that when individuals from non‐dominant cultural groups, such as ethnic minorities, acculturate, they are faced with two important decisions: (1) is it important to maintain one's original culture and identity? and (2) is it important to maintain intergroup relations with the dominant cultural group? The yes‐or‐no responses to these two questions, which are assumed to be independent, intersect to form four acculturation orientations. An integration orientation occurs when an individual values both the maintenance of their original culture and their relationship with the dominant group; but if neither is important, marginalisation results. If an individual only values their original culture, separation occurs; however, if an individual only values their relationship with the dominant group, then assimilation occurs. At this juncture, it is important to emphasise that acculturation is a process through which cultural identity can change (Berry, Citation2003; Schwartz et al., Citation2006). In this sense, the concept of a bicultural identity could be considered an important outcome of the integration orientation, whereby ethnic minorities integrate their heritage culture and the culture of the dominant group into their sense of self (Berry & Sam, Citation1996).

Berry's (Citation1997) acculturation orientation model has also heavily influenced the measurement of bicultural identities. Consistent with previous acculturation research and theory, the most widely used approach to operationalise bicultural identity is to assume that it is a bidimensional construct, where identification with one's heritage (e.g., ethnic) and the dominant (e.g., national) cultural groups can be measured on two separate scales (Nguyen & Benet‐Martínez, Citation2007, Citation2010; Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, Citation2000; Zane & Mak, Citation2003). Typically, when an individual is highly identified with both cultural groups, they are considered ‘bicultural’. While this approach ostensibly allows researchers to measure an identity akin to the outcome of Berry's integration orientation, researchers are inconsistent in the way they utilise these two separate scales to infer biculturalism. First, a typological method is used, whereby participants above a predetermined cut‐off score on both scales, such as the midpoint of the scale or the median score, are considered bicultural and differentiated from other acculturating types (e.g., Phinney, Citation1992; Tsai, Ying, & Lee, Citation2000). However, this approach does not provide a biculturalism score, and the cut‐off is often arbitrary, and therefore, not directly interpretable, making cross‐cultural and cross‐sectional comparisons difficult. Second, an additive or multiplicative method is used, whereby the scales are added (e.g., Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, Citation1995) or multiplied (e.g., Birman, Citation1998) to form a bicultural identification score. A limitation of these methods is that between‐subject comparisons become difficult, as participants who score high on one scale and low on the other, and participants with medium scores on both scales, become indistinguishable from each other. Last, a subtractive method is used whereby the scales are subtracted from each other, with a score of zero being indicative of bicultural identification (e.g., Szapocznik, Kurtines, & Fernandez, Citation1980). Again, this method does not distinguish between participants who are high or low on both scales. As this very brief discussion demonstrates, there exist a number of non‐trivial limitations associated with this bidimensional approach to bicultural identity measurement.

However, researchers from different fields of psychology are beginning to argue that a bicultural identity may be more appropriately conceptualised as a hyphenated cultural identity (e.g., Chinese‐Australian), which represents a ‘third’ identity that is not merely reducible to the sum of its parts (Benet‐Martínez & Haritatos, Citation2005; Chu, Citation2016; Fine & Sirin, Citation2007; Fleischmann & Verkuyten, Citation2016; Phinney, Citation2003; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002; Simon & Ruhs, Citation2008; Verkuyten, Citation2014). In support of this conceptualisation, Amiot, de la Sablonnière, Terry, and Smith (Citation2007) have argued that individuals are capable of coherently integrating multiple and distinct social identities, such that ethnic and national identities can become simultaneously important to their sense of self. Roccas and Brewer (Citation2002) have similarly theorised that, in the context of acculturation, a hyphenated cultural identity can form at the intersection of an individual's ethnic and national identities. In their theoretical model, this new identity is more than the simple amalgamation of the subgroup identities; it represents the unique identity that emerges from specific cultural experiences of ethnic minority identities within the context of the dominant national culture (Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002).

Importantly, Fleischmann and Verkuyten (Citation2016) brought to our attention the work of Simon and Ruhs (Citation2008), who previously argued that assessing bicultural identities on separate ethnic and national identification measures ‘may be too mechanistic and restrictive to adequately capture the rich phenomenology of dual (hyphenated or hybrid) identity in the context of migration’ (Simon & Ruhs, Citation2008, p. 1355). In the context of their collective action research amongst Turkish migrants in Germany, Simon and Ruhs argued that assuming that an individual is biculturally identified when they are highly identified with both their ethnic and national identity is problematic because ‘[w]e simply do not know whether the combination of maximal component identifications is also the optimal combination for dual identity’ (p. 1335). Based on this reasoning, we contend, in a similar vein to Simon and Ruhs and Fleischmann and Verkuyten, that a more nuanced approach for assessing bicultural identification may be to directly measure the extent to which individuals identify with a hyphenated cultural identity (e.g., ‘In general, being Chinese‐Australian is an important part of my self‐image’ and ‘I feel strong ties to other Chinese‐Australians’). To this end, an individual is considered bicultural when they are highly identified with this hyphenated cultural group.

ASSESSING HYPHENATED CULTURAL IDENTITIES AMONGST ETHNIC MINORITIES

Adopting this conceptual approach, Fleischmann and Verkuyten (Citation2016) recently conducted a large‐scale survey examining multiple, hyphenated cultural identities in the Netherlands. They found preliminary evidence to suggest that strong ethnic (e.g., Chinese, Afghani, Iraqi) and national (i.e., Dutch) identification only partially accounted for identification with a hyphenated cultural label (e.g., Chinese‐Dutch, Afghani‐Dutch, Iraqi‐Dutch). Adapting this approach, Chu (Citation2016) recently provided the first empirical assessment of hyphenated cultural identities amongst a sample of Australian participants with Asian heritage. Expanding on the methodology of Fleischmann and Verkuyten, where ethnic, national, and hyphenated cultural identification were simply assessed via two items, identification was measured on a more comprehensive and validated measure of social identification (see Cameron, Citation2004). Specifically, participants completed three versions of this multi‐item measure to assess hyphenated cultural identification (e.g., ‘In general, I'm glad to be Chinese‐Australian’), ethnic identification (e.g., ‘In general, I'm glad to be Chinese’), and Australian identification (e.g., ‘In general, I'm glad to be Australian’).

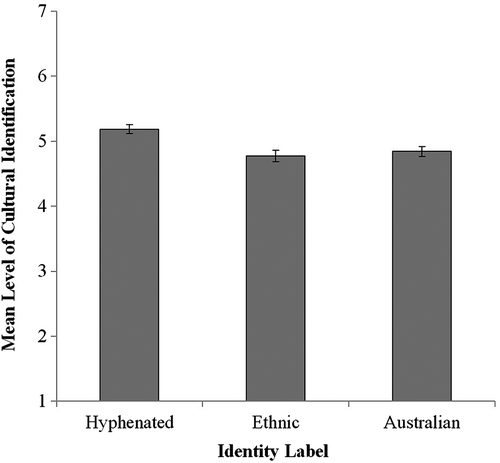

As shown in Fig. 1, the results demonstrated that participants most strongly identified with a hyphenated cultural identity relative to an ethnic or Australian identity label (Chu, Citation2016). There were no differences between ethnic and Australian identification. Importantly, ethnic and Australian identification only accounted for 40% of the variability in participants’ identification with a hyphenated cultural identity. This provides further support for the contention that identification with a hyphenated cultural identity was not merely reducible to the sum of the two subgroup identities.

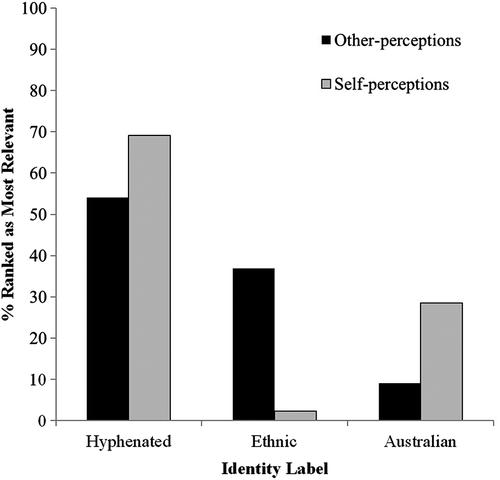

Chu (Citation2016) also asked participants to rank the relevance, from most to least, of an ethnic, Australian, and hyphenated cultural identity to their sense of self and belonging. Participants also ranked these same identities on the basis of how they thought ‘others’ would perceive them. Fig. 2 illustrates the proportion of times (as a percentage) each identity label was ranked as ‘most relevant’ from the perspective of the self and others. The results demonstrated that while Asian‐Australians viewed their hyphenated cultural identity as more self‐relevant than their ethnic or Australian identity, they also recognised that outgroup members do not necessarily share this perception.

Together, these findings highlight the importance of measuring and understanding hyphenated cultural identities amongst ethnic minorities at both an individual and group level. In particular, these findings raise two important research questions: (1) what impact, if any, does biculturalism have on these individuals’ lives? and (2) what impact, if any, does the misrecognition of biculturalism have for intergroup relations in multicultural societies, like Australia? In the next section, we will evaluate these two important questions in light of the existing theory and research.

THE IMPACT OF BICULTURALISM FOR INDIVIDUALS AND SOCIETY

Much of the existing psychological research attests to the idea that social identities provide individuals with a strong sense of belonging, which is important for wellbeing and resilience against adversity (Jetten, Haslam, & Haslam, Citation2012). Bicultural identities have similarly been found to result in a number of positive self‐outcomes. In a meta‐analytic review of 83 studies (n = 23,197), Nguyen and Benet‐Martínez (Citation2013) found a moderate and positive relationship between bicultural identification and adjustment (both psychological, e.g., life satisfaction, self‐esteem, and sociocultural, e.g., academic achievement, career success). While their findings suggested that identification with any culture (i.e., ethnic, dominant, or both) was positively associated with adjustment, this relationship was the strongest for bicultural identification. This may be a result of the increased cognitive complexity and flexibility that bicultural individuals develop as they navigate both the dominant and ethnic cultures (Benet‐Martínez, Lee, & Leu, Citation2006; Tadmor, Galinsky, & Maddux, Citation2012; Tadmor, Tetlock, & Peng, Citation2009), alongside the benefits of having social support networks from both cultural groups (Mok, Morris, Benet‐Martínez, & Karakitapoglu‐Aygun, Citation2007). This finding might explain why bicultural identification is associated with greater resilience against adversity and discrimination (Huynh, Devos, & Goldberg, Citation2014). For example, in one study examining the negative impact of being a witness to domestic violence in a group of South‐East Asian youths living in The United States, it was found that those who were more strongly identified with both their ethnic and national identity were more resilient in comparison to youth who only identified with one cultural identity (Sirikantraporn, Citation2013).

There are, however, two important considerations to make when interpreting this body of research. First, many of the above findings are based on a bidimensional measurement of bicultural identification, where bicultural identity was indirectly measured via scores on both ethnic and national identity scales. To the authors’ knowledge, there has been no direct measurement of hyphenated cultural identities, or a comparison of the bidimensional and hyphenated cultural approaches, when examining the intrapersonal benefits of biculturalism. Future research is required in this regard (see Fleischmann & Verkuyten, Citation2016). Second, Benet‐Martínez and coworkers (Benet‐Martínez & Haritatos, Citation2005; Chen, Benet‐Martínez, & Bond, Citation2008; Chen, Benet‐Martínez, Wu, Lam, & Bond, Citation2013) have attempted to extend this research by examining how individual variations in the experience of biculturalism can moderate the relationship between bicultural identification and psychosocial outcomes. To this end, they have primarily focused on the theoretical construct of bicultural identity integration (see Huynh, Nugyen et al., 2011), which they conceptualise as the extent to which people perceive and experience two cultural identities as integrated (e.g., ‘I combine both cultures’) vs. oppositional (e.g., ‘I feel conflicted between the two cultures’). Past research has typically found a positive relationship between bicultural identity integration and adjustment (Chen et al., Citation2008, Citation2013). Although Benet‐Martínez and Haritatos (Citation2005) have proposed that bicultural identity integration might be a psychological antecedent for hyphenated cultural identification, where ‘[i]ndividuals high on [bicultural identity integration] tend to see themselves as part of a “hyphenated culture” (or even part of a combined, “third,” emerging culture)’ (p. 1019; see also Hornsey & Hogg, Citation2000), bicultural identity integration may also moderate the relationship between hyphenated bicultural identification and psychosocial outcomes as it was originally conceptualised. Future research is needed to disentangle this relationship and empirically evaluate whether the outcomes associated with a hyphenated bicultural identity are also influenced by individual differences in the experience of a hyphenated culture.

Researchers have also argued that bicultural identities are beneficial for society (Berry, Citation1998). Unfortunately, while it has been suggested that social policies that support multiculturalism may lead to greater national productivity (Schwartz et al., Citation2006) and fewer intercultural conflicts (Nguyen & Benet‐Martínez, Citation2007), in practice, many host societies encourage ethnic minorities, many of whom identify as bicultural, to assimilate (van Oudenhoven et al., Citation2006). Interestingly, the Australian data presented above indicates that from a minority perspective, while Asian‐Australians prefer a hyphenated cultural identity, they also acknowledge that others do not share this preference (Chu, Citation2016). This discordance in acculturation orientations between ethnic majority and minority group members has been shown to result in feelings of intergroup threat (Rohmann, Piontkowski, & van Randenborgh, Citation2008; Ward, Citation2009). These findings should also be interpreted in light of the growing body of evidence that is suggesting that bicultural individuals may regard their hyphenated cultural identity as an aspect of their self‐concept that requires active acknowledgement from others (Chu, Citation2016). In other words, bicultural individuals may prefer their hyphenated cultural identity to be accurately recognised, rather than misrecognised or denied, by the majority group.

Although there is limited research directly examining the short‐ and long‐term consequences of not recognising bicultural identities, research has found that misrecognition of important identities can lead to poor self‐outcomes (see Kang & Bodenhausen, Citation2015). For example, being denied self‐relevant cultural identities is associated with various negative outcomes for both psychological (e.g., reduced life satisfaction, greater depression) and physical (e.g., unhealthy food choices) wellbeing, even when accounting for the contribution of discrimination (Guendelman, Cheryan, & Monin, Citation2011; Huynh, Devos et al., 2011). Such instances of cultural identity misrecognition also have the potential to result in negative intergroup consequences. For example, ethnic minorities who have their cultural identity misrecognised by an interaction partner evaluate this partner more negatively and become more reluctant to interact with them in the future (Remedios & Chasteen, Citation2013; Townsend et al., Citation2009). This is because interactions that do not verify one's self‐views are perceived as threatening (Swann & Brooks, Citation2012). Crucially, the consequences of identity misrecognition have been shown to extend beyond the immediate situation, with negative feelings generalising towards the interaction partners’ entire group (Flores & Huo, Citation2013). Given the prevalence of bicultural identities worldwide (van Oudenhoven et al., Citation2006), future research is required to extend these past findings in relation to biculturalism.

In a parallel line of intergroup relations research, some ethnic minorities have been shown to strongly prefer settings that simultaneously acknowledge intergroup similarities (e.g., the common, national identity) and ethnic group differences (Dovidio et al., Citation2009; White & Abu‐Rayya, Citation2012; White, Abu‐Rayya, & Weitzel, Citation2014). This finding can be extended to include hyphenated cultural identities, which allow ethnic minorities to maintain a sense of duality in the intergroup setting, without the need to relinquish either the ethnic or national identity. In contrast, however, majority group members show a preference for common identity representations, whereby both majorities and minorities are required to conceive of themselves under a single, superordinate, and shared identity (e.g., ‘We are all Australian’). These different identity preferences may arise from different motivations. Specifically, a dual identity representation allows ethnic minorities to satisfy their motivation to challenge the status quo and improve their position in society, whereas a common identity representation allows ethnic majorities to satisfy their need to maintain their privileged status and preserve the system that advantages them (Dovidio et al., Citation2009).

These preferred identities, however, might depend on the social and historical context (Bourhis et al., Citation1997), which in turn may influence minority and majority motivations. For example, in contexts where ethnic minorities strive to differentiate themselves from the dominant culture, minority individuals may be less motivated to integrate a second cultural identity into their self‐concept (see Abu‐Rayya, Walker, White, & Abu‐Rayya, Citation2016). Similarly, in contexts where ethnic minorities strive for assimilation and equal status with the dominant group, minority individuals may be motivated to relinquish their minority identity and solely identify with the majority (see Guerra et al., Citation2010). Therefore, bicultural identification may only be functional insofar as it permits the minority group in achieving their acculturation goals in the majority culture. On this note, it is important to highlight that the data presented above was drawn from a sample of Asian minorities living in Australia and whose acculturation goals are likely to be orientated towards integrating their cultural identity with the dominant culture (Chu, Citation2016). Consequently, the findings may not be representative of all ethnic minority experiences in Australia or worldwide. The degree of hyphenated identification may depend on the specific historical and cultural context of intergroup relations, which may affect individuals’ acculturation orientations (Berry, Citation1997).

Together, this research demonstrates the complexities associated with biculturalism. On the one hand, bicultural identities have numerous positive psychological and sociocultural outcomes for individuals, but on the other, misrecognising bicultural identities has potentially adverse consequences for intergroup relations. It is therefore important for acculturation, biculturalism, and intergroup relations researchers to continue to examine biculturalism in order to adequately understand its function at an individual and group level. As maintained in this review, a valuable first step may be to adopt a hyphenated operational definition of bicultural identity, which we contend taps into the nuances of bicultural identities in the context of the migrant experience (Chu, Citation2016; Fleischmann & Verkuyten, Citation2016; Simon & Ruhs, Citation2008).

CONCLUSION

This review has attempted to integrate disparate literatures on acculturation, biculturalism, and intergroup relations. It has also underscored the importance of acknowledging a minority perspective in the context of fostering and maintaining social harmony between both majorities and minorities (White, Harvey, & Verrelli, Citation2015). In view of the significant role that cultural identities play in intergroup relations (e.g., Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, Citation1999), it is important that ethnic minorities' preferred identities are accurately recognised and understood. One potential caveat of this argument is that these identity processes may operate differently within different ethnic groups. Nonetheless, this review has reviewed evidence to support the view that for at least Asians living in Australia, the most self‐relevant cultural identity is their hyphenated one (e.g., Chinese‐Australian), rather than an ethnic (e.g., Chinese) or national (e.g., Australian) identity. If Asians living in Australia prefer a hyphenated cultural identity, then it is important that the dominant ethnic group acknowledge this identity during intergroup interactions. Importantly, we have attempted to start a conversation on the relevance of acknowledging biculturalism for promoting positive intergroup relations. To echo the sentiments of Kabir (Citation2015, p. 95), ‘biculturalism should be a cultural capital for a cohesive society’. A more inclusive awareness and understanding of bicultural identity will afford multicultural societies, like Australia, the ability to prosper in a number of domains, including innovation, education, and community cohesion.

REFERENCES

- ABS. (2012). Reflecting a nation: Stories from the 2011 census, 2012–2013. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/2071.0

- Abu‐rayya, M. H. , Walker, R. , White, F. A. , & Abu‐rayya, H. M. (2016). Cultural identification and religious identification contribute differentially to the adaptation of Australian adolescent Muslims. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 54, 21–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.07.002

- Amiot, C. E. , de la Sablonnière, R. , Terry, D. J. , & Smith, J. R. (2007). Integration of social identities in the self: Toward a cognitive‐developmental model. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 364–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307304091

- Arnett, J. J. (2002). The psychology of globalization. American Psychologist, 57, 774–783. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003‐066X.57.10.774

- Benet‐martínez, V. , & Haritatos, J. (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality, 73, 1015–1050. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐6494.2005.00337.x

- Benet‐martínez, V. , Lee, F. , & Leu, J. (2006). Biculturalism and cognitive complexity expertise in cultural representations. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 37, 386–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106288476

- Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46, 5–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464‐0597.1997.tb01087.x

- Berry, J. W. (1998). Social psychological costs and benefits of multiculturalism: A view from Canada. Trames, 2, 209–233.

- Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun , P. B. Organista , & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17–37). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Berry, J. W. (2008). Globalisation and acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32, 328–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.04.001

- Berry, J. W. , & Sam, D. (1996). Acculturation and adaptation. In J. Berry , M. Segall , & C. Kagitcibasi (Eds.), Handbook of cross‐cultural psychology: Social behavior and applications (Vol. 3, pp. 291–325). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Birman, D. (1998). Biculturalism and perceived competence of Latino immigrant adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26, 335–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022101219563

- Bourhis, R. Y. , Moïse, L. C. , Perreault, S. , & Senecal, S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32, 369–386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/002075997400629

- Branscombe, N. R. , Schmitt, M. T. , & Harvey, R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well‐being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.77.1.135

- Cameron, J. E. (2004). A three‐factor model of social identity. Self and Identity, 3, 239–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000047

- Chen, S. X. , Benet‐martínez, V. , & Bond, M. H. (2008). Bicultural identity, bilingualism, and psychological adjustment in multicultural societies: Immigration‐based and globalization‐based acculturation. Journal of Personality, 76, 803–838. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐6494.2008.00505.x

- Chen, S. X. , Benet‐martínez, V. , Wu, W. C. , Lam, B. C. , & Bond, M. H. (2013). The role of dialectical self and bicultural identity integration in psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 81, 61–75.

- Cheryan, S. , & Monin, B. (2005). Where are you really from?: Asian Americans and identity denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 717–730. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.89.5.717

- Chu, E. (2016). Asian Australian hyphenated identification: Self and other perceptions and their implications for intergroup relations (Unpublished doctoral thesis). The University of Sydney, Australia.

- Cuellar, I. , Arnold, B. , & Maldonado, R. (1995). Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans‐II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17, 275–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/07399863950173001

- Department of Immigration and Border Protection. (2014). The people of Australia: Statistics from the 2011 census. Retrived from: https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people‐australia‐2013‐statistics.pdf

- Dovidio, J. F. , Gaertner, S. L. , & Saguy, T. (2009). Commonality and the complexity of “we”: Social attitudes and social change. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 3–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308326751

- Fine, M. , & Sirin, S. R. (2007). Theorizing hyphenated selves: Researching youth development in and across contentious political contexts. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 16–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751‐9004.2007.00032.x

- Fleischmann, F. , & Verkuyten, M. (2016). Dual identity among immigrants: Comparing different conceptualizations, their measurements, and implications. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22, 151–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000058

- Flores, N. M. , & Huo, Y. J. (2013). “We” are not all alike: Consequences of neglecting national origin identities among Asians and Latinos. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4, 143–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612449025

- Guendelman, M. D. , Cheryan, S. , & Monin, B. (2011). Fitting in but getting fat identity threat and dietary choices among us immigrant groups. Psychological Science, 22, 959–967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611411585

- Guerra, R. , Rebelo, M. , Monteiro, M. B. , Riek, B. M. , Mania, E. W. , Gaertner, S. L. , & Dovidio, J. F. (2010). How should intergroup contact be structured to reduce bias among majority and minority group children? Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 13, 445–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209355651

- Hong, Y. , Zhan, S. , Morris, M. W. , & Benet‐martínez, V. (2016). Multicultural identity processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 49–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.020

- Hornsey, M. J. , & Hogg, M. A. (2000). Assimilation and diversity: An integrative model of subgroup relations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 143–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_03

- Huo, Y. J. , Molina, L. E. , Binning, K. R. , & Funge, S. P. (2010). Subgroup respect, social engagement, and well‐being: A field study of an ethnically diverse high school. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 427–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019886

- Huynh, Q. L. , Devos, T. , & Goldberg, R. (2014). The role of ethnic and national identifications in perceived discrimination for Asian Americans: Toward a better understanding of the buffering effect of group identifications on psychological distress. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5, 161–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031601

- Huynh, Q.‐L. , Devos, T. , & Smalarz, L. (2011). Perpetual foreigner in one's own land: Potential implications for identity and psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30, 133–162.

- Huynh, Q.‐L. , Nguyen, A.‐M. D. , & Benet‐martínez, V. (2011). Bicultural identity integration. In S. J. Schwartz , K. Luyckx , & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 827–844). New York, NY: Springer.

- Jetten, J. , Haslam, C. , & Haslam, S. A. (Eds). (2012). The social cure: Identity, health and well‐being. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Kabir, N. A. (2015). Muslim youth's identity in Australia: Vigilant, rational and bicultural. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 1, 82–96.

- Kang, S. K. , & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2015). Multiple identities in social perception and interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 547–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev‐psych‐010814‐015025

- Lafromboise, T. , Coleman, H. L. , & Gerton, J. (1993). Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 395–412. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.114.3.395

- Mok, A. , Morris, M. , Benet‐martínez, V. , & Karakitapoglu‐aygun, Z. (2007). Embracing American culture: Structures of social identity and social networks among first‐generation biculturals. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 38, 629–635. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107305243

- Morris, M. W. , Chiu, C. Y. , & Liu, Z. (2015). Polycultural psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 631–659. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev‐psych‐010814‐015001

- Nguyen, A.‐M. D. , & Benet‐martínez, V. (2007). Biculturalism unpacked: Components, measurement, individual differences, and outcomes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 101–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751‐9004.2007.00029.x

- Nguyen, A.‐M. D. , & Benet‐martínez, V. (2010). Multicultural identity: What it is and why it matters. In R. J. Crisp (Ed.), The psychology of social and cultural diversity (pp. 87–114). West Sussex, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Nguyen, A.‐M. D. , & Benet‐martínez, V. (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 44, 122–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111435097

- Phinney, J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/074355489272003

- Phinney, J. S. (2003). Ethnic identity and acculturation. In K. M. Chun , P. Balls organista , & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 63–81). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Remedios, J. D. , & Chasteen, A. L. (2013). Finally, someone who “gets” me! Multiracial people value others' accuracy about their race. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 453–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032249

- Roccas, S. , & Brewer, M. B. (2002). Social identity complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 88–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_01

- Rohmann, A. , Piontkowski, U. , & van Randenborgh, A. (2008). When attitudes do not fit: Discordance of acculturation attitudes as an antecedent of intergroup threat. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 337–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207311197

- Ryder, A. G. , Alden, L. E. , & Paulhus, D. L. (2000). Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head‐to‐head comparison in the prediction of personality, self‐identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 49–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.79.1.49

- Schwartz, S. J. , Montgomery, M. J. , & Briones, E. (2006). The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development, 49, 1–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000090300

- Schwartz, S. J. , & Unger, J. B. (2010). Biculturalism and context: What is biculturalism, and when is it adaptive? Human Development, 53, 26–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000268137

- Simon, B. , & Ruhs, D. (2008). Identity and politicization among Turkish migrants in Germany: The role of dual identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1354–1366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012630

- Sirikantraporn, S. (2013). Biculturalism as a protective factor: An exploratory study on resilience and the bicultural level of acculturation among Southeast Asian American youth who have witnessed domestic violence. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4, 109–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030433

- Statistics Canada. (2013). 2011 National Household Survey. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/

- Statistics New Zealand. (2014). 2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/

- Swann, W. B. , & Brooks, M. (2012). Why threats trigger compensatory reactions: The need for coherence and quest for self‐verification. Social Cognition, 30, 758–777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2012.30.6.758

- Szapocznik, J. , Kurtines, W. M. , & Fernandez, T. (1980). Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic‐American youths. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 4, 353–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0147‐1767(80)90010‐3

- Tadmor, C. T. , Galinsky, A. D. , & Maddux, W. W. (2012). Getting the most out of living abroad: Biculturalism and integrative complexity as key drivers of creative and professional success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, 520–542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029360

- Tadmor, C. T. , Tetlock, P. E. , & Peng, K. (2009). Acculturation strategies and integrative complexity: The cognitive implications of biculturalism. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 40, 105–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022108326279

- Townsend, S. S. , Markus, H. R. , & Bergsieker, H. B. (2009). My choice, your categories: The denial of multiracial identities. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 185–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540‐4560.2008.01594.x

- Tsai, J. L. , Ying, Y. W. , & Lee, P. A. (2000). The Meaning of “being Chinese” and “being American” variation among Chinese American young adults. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 31, 302–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022100031003002

- van Oudenhoven, J. P. , Ward, C. , & Masgoret, A. M. (2006). Patterns of relations between immigrants and host societies. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 637–651. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.09.001

- Verkuyten, M. (2004). The social psychology of ethnic identity. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Verkuyten, M. (2014). Identity and cultural diversity: What social psychology can teach us. London, UK: Routledge.

- Verkuyten, M. (2016). Dual identity and immigrants' protest against discrimination: The moderating role of diversity ideologies. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216629813

- Ward, C. (2009). Acculturation and social cohesion: Emerging issues for Asian immigrants in New Zealand. In C.‐H. Leong & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Intercultural relations in Asia: Migration and work effectiveness (pp. 3–24). Singapore, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company.

- White, F. A. , & Abu‐rayya, H. M. (2012). A dual identity‐electronic contact (DIEC) experiment promoting short‐ and long‐term intergroup harmony. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 597–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.01.007

- White, F. A. , Abu‐rayya, H. M. , & Weitzel, C. (2014). Achieving twelve‐months of intergroup bias reduction: The Dual Identity E‐contact (DIEC) experiment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 158–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.002

- White, F. A. , Harvey, L. J. , & Verrelli, S. (2015). Including both voices: A new bidirectional framework for understanding and improving intergroup relations. Australian Psychologist, 50, 421–433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12108

- Zane, N. , & Mak, W. (2003). Major approaches to the measurement of acculturation among ethnic minority populations: A content analysis and an alternative empirical strategy. In K. M. Chun , P. B. Organista , & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 39–60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.