Abstract

The Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) is by far the most comprehensive change to the patent law in at least half a century. Implementation of the AIA has been ongoing, but the final and most critical provisions went into effect on March 16, 2013. Although, it will take several years before we fully understand the law's impact, the new law is likely to fundamentally change the way innovation is protected within the United States. Researchers will need to become increasingly vigilant as to publication dates as well as communications coming from their labs.

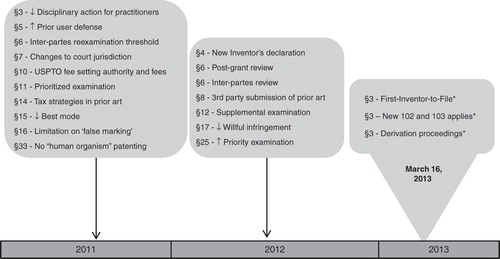

The Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), which was enacted on September 16, 2011, is by far the most comprehensive change to the Patent Law in at least half a century Citation[1]. The AIA was enacted under a ‘rolling implementation' scheme in which various provisions have gone into effect over the past year and a half, with final implementation on March 16, 2013 (). Because of the nature of the implementation, it will take several years before we fully understand the law's impact; however, it has the potential to fundamentally change the way innovation is protected within the United States.

Figure 1. A timeline showing implementation of the AIA, indicating the year in which the provision became effective. Many provisions became effective in the fall of 2011 or on September 16, 2012 (one year after enactment), but the final provisions were not effective until eighteen months after enactment, i.e., March 16, 2013. Some provisions generally apply only to applications with an effective filing date after March 15, 2013.

1. An overview of the AIA

The AIA is the culmination of a decade long debate on how to ‘improve patent quality' arising from a series of studies on the relationship of Patent Law to the economy Citation[2]. In 2005, Representative Lamar Smith of Texas proposed the first version and, between 2005 and 2011, revised patent reform bills were proposed which were widely criticized by various stakeholders. The opposition focused primarily on three features: a provision limiting damages in patent infringement cases; post-grant revocation proceedings; and a ‘first-to-file' provision. The bills were heavily supported by high tech sectors but largely opposed by bio-pharma and academic sectors. In 2011, Senator Patrick Leahy introduced an amended version of the patent reform legislation which removed or dampened the most controversial provisions of the law and allowed passage of the AIA. Since its passage, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has invested in an extraordinary effort in developing rules to implement the AIA, reviewing hundreds of public comments and expending resources on multiple national road shows to allow customer input on its proposals.

Until March, 2013, the changes that had gone into effect were felt most keenly by commercial entities. For example, there were changes to the nature of ‘patent marking' which has drastically reduced the amount of money and effort that companies need to expend responding to the deluge of recent lawsuits asserting a charge of false marking. These provisions however, are somewhat transparent to the research sector.

shows a more comprehensive chart of substantive provisions of the AIA. Although, many provisions fundamentally change the nature of patent protection, the areas that are most relevant for biomedical researchers in practice are: changing from first-to-invent to first-to-file; and the new standard for prior art.

Table 1. Relevant substantive provisions of the AIA.

1.1 First-to-file

Up until March 16, 2013, the United States had focused on who ‘invented' a claimed invention rather than on who filed the patent application itself Citation[3]. This standard was unique to the United States and the AIA has been promoted as a mechanism to conform to international standards. Most researchers are familiar with a need to document their conception dates and keep appropriately witnessed notebooks. This requirement is, unfortunately not eliminated in the AIA and, indeed, has been expanded. The new focus will be on whether a ‘first filing inventor' obtained, or could have obtained, the invention from a ‘later filer' Citation[4].

Under the AIA, an inventor on a later-filed patent application can attempt to prove that an earlier-filed invention was derived from them. Such a ‘Derivation Proceeding' must be requested within a one year timeframe from publication of the ‘derived' claims and be supported by ‘substantial evidence.' In September 2012, the USPTO issued guidance on what must be included in such evidence Citation[5]. To petition for a Derivation Proceeding on a ‘patentably indistinct' invention, a petitioner has to show both earlier conception by as well as communication to the other party. The USPTO requires that the petitioner corroborate the earlier conception and include at least one corroborated affidavit addressing the communication of the invention to the other party.

1.2 Prior art

A major revision instituted in the AIA is a change to what constitutes ‘prior art' against an invention. Before the AIA, a person was generally entitled to an invention unless: (a) prior to the date of invention, it was patented or described in print, or known or used by others in the United States Citation[6]; or (b) more than one year before the filing date, the invention was patented or published by anyone or on sale in the United States Citation[7].

The AIA eliminated these provisions and instead includes as prior art anything that is ‘patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public' prior the filing date of the claimed invention Citation[8]. There is much debate over how the courts will interpret ‘otherwise available to the public' but it is generally accepted that this phrase expands the scope of prior art. The law also, for the first time, uses the filing date of a foreign application as its prior art date. The USPTO will interpret prior art to include not only all printed publications, patents and patent applications, but also any other publication (including theses, poster displays, ‘information disseminated at a scientific meeting,' and even non-sale commercial transactions) so long as they make the invention ‘sufficiently available to the public' Citation[9].

On its face, the AIA retains certain protections for researchers, first and foremost a grace period for an inventor's own disclosures. Retention of the grace period was critical in allowing the bill's passage. Specifically, a disclosure made within one year before filing is not prior art if: (a) it was made by the inventor, by someone who obtained it directly or indirectly from the inventor, or under a joint research agreement; or (b) it was made by a third party but the inventor made an earlier public disclosure Citation[10].

In February 2013, after extensive public comment, the USPTO issued a final set of rules that more clearly defined how the patent office intends to treat this grace period. One controversial area is the exception under 102(b)(1)(B) that allows that a third party publication made a year or less before disclosure can be disregarded as prior art if it occurred after the inventor publicly disclosed the subject matter. The USPTO has clarified that the intervening disclosure does not need to be either verbatim or made in the same mode as the original disclosure, and has further clarified that the exception also applies to more general descriptions of an earlier disclosure. However, the USPTO has also clarified that if an intervening disclosure is either a narrowing of an earlier broad concept, or if it is a different species than previously disclosed, it will be considered prior art Citation[11].

One of the changes in the AIA that could benefit biomedical researchers is a broader protection for collaborative research. Disclosures in an earlier-filed patent application are eliminated from prior art if they are co-owned, and applications are considered co-owned if the current invention was made under a joint research agreement. Prior to the AIA, the joint research agreement had to be in place before the invention existed Citation[12]. This places an additional burden on academic researchers who often interact in informal collaborations, and often the conception of a new invention is the impetus to formalize such a relationship. Under the AIA, a joint research agreement need merely be ‘in effect on or before the effective filing date' of an application Citation[13]. Therefore, there is now more flexibility to enter into formal research arrangements for collaborative research, so long as these are completed prior to filing of a new patent application.

2. Additional major considerations

Several additional provisions of the law will likely have a delayed effect on biomedical researchers but are worthy of a mention. One area is the new post-grant review provision. Until the implementation of the AIA, there were very limited options for a third party to call into question, the validity of an issued patent at the USPTO. However, under the AIA, any third party may challenge any newly issued patent on any grounds for nine months after issuance. After the nine month window, a much more limited review remains available throughout the life of a patent. This new post-grant review period is only generally available on patents that issue from applications filed after March 16, 2013, therefore we will likely not see it in practice for at least another year.

Another issue that researchers may run across is the removal of the ‘best mode' requirement as grounds for invalidating a patent. This provision has received significant attention by patent attorneys. The ‘best mode' requirement states that, in order to obtain a patent, the ‘best mode contemplated by the inventor or joint inventor of carrying out the invention' must be disclosed to the public (see 35 U.S.C. §112(a)). The idea harkens back to the fundamental contract that a patent represents: the federal government provides a limited monopoly on a patented technology, and in return the inventor gives all the information necessary to practice the invention to the public. As soon as the patent expires, the full scope of the invention is then in the public domain to avoid the use of trade secrets. If a patent cannot be invalidated for a lack of disclosure of the ‘best mode,' then it may drive inventors to retain certain ideas in house. For instance, take the case of a new small molecule cancer treatment that can, theoretically, be synthesized in miniscule quantities using a 20-step process but the inventor has also developed a 90%-yield, 2-step process; must the inventor disclose the new process? If the new process is kept a trade secret, it likely provides a significant commercial advantage while still allowing patent protection on the new molecule itself. That being said, because the ‘best mode' requirement is retained in the AIA for obtaining a patent even though one cannot invalidate a patent if it is violated, it raises the issue of how such a requirement can be enforced.

3. Implications for researchers

Enactment of the AIA is particularly challenging in the biomedical research arena, in which the environment of ‘publish or perish' makes the changes to prior art and first-to-file provisions particularly relevant. The AIA is not the only recent development in patent law that affects the ability of researchers to develop new technologies. Over the past decade the courts have taken on a variety of patent cases that have reduced patent protection Citation[14]. Under the AIA, researchers are no longer protected by early conception, and disclosures to third parties can be extremely costly. Document retention, focusing on both conception and disclosure to third parties, will become critical. Further, ensuring that disclosures are made under confidentiality or other agreements will become increasingly more important as the AIA goes fully into effect. As the AIA comes into full effect, it will be interesting to see whether commercial groups continue to rely on patent protection to the same extent.

Notes

Bibliography

- On January 14, 2013, President Obama signed a bill (HR 6621) that included certain corrections however the substance of the major provisions remains the same

- Merrill SA, Levin RC, Myers MB. editor. A patent system for the 21st century. Committee on Intellectual Property Rights in the Knowledge-Based Economy, Nat'l Res. Council Nat'l Acad. Press; 2004

- See pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. §102(g)(2) which provides that a person is “entitled to a patent unless…before such person's invention thereof, the invention was made in this country by another inventor who had not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed it.”

- See AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1) and 78 Fed. Reg. 11024 at at 11035-6 (February 14, 2013); See also, e.g., Letter from Holbrook and Janis to Congress (June 13, 2011)

- 77 Fed. Reg.56068 (September 11, 2012)

- See pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. §102(a) and (e)

- See pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. §102(b) and (d)

- 35 U.S.C. §102(a)(1)

- See Examination Guidelines, 78 Fed. Reg. 11059 at 11074-75 (February 14, 2013)

- 35 U.S.C. §102(b)

- 78 Fed. Reg. 11024 and see Examination Guidelines, 78 Fed. Reg.11059 at 11077

- See 35 U.S.C. 103(c); This statute was amended in response to the CREATE Act of 2004 to increase cooperative academic research by removing a patentability bar on sharing of information between unrelated entities so long as they had entered a Joint Research Agreement

- 35 U.S.C. 102(c)

- See e.g., eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006) and Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc., 553 U.S. 617 (2008)); Merck KGaA v. Integra Lifesciences I, Ltd., 545 U.S. 193 (2005) (limiting patent protection during clinical development); Assn. Molecular Pathology v. U.S.P.T.O., 653 F.3d 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2011) and Prometheus Labs, Inc. v. Mayo Collaborative Services, 131 S. Ct. 3027 (2011) (making it difficult to patent diagnostics); Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v Eli Lilly 598 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc) (heightening the standard to patent fundamental technologies); and KSR Int'l Co., v. Teleflex, Inc. et al, 550 U.S. 398 (2007) (expanding the tests for obviousness).