Abstract

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) was introduced in 1995 to address the problem of recurrent depression. MBCT is based on the notion that meditation helps individuals effectively deploy and regulate attention to effectively manage and treat a range of psychological symptoms, including emotional responses to stress, anxiety, and depression. Several studies demonstrate that mindfulness approaches can effectively reduce negative emotional reactions that result from and/or exacerbate psychiatric difficulties and exposure to stressors among children, adolescents, and their parents. Mindfulness may be particularly relevant for youth with maladaptive cognitive processes such as rumination. Clinical experience regarding the utility of mindfulness-based approaches, including MBCT, is being increasingly supported by empirical studies to optimize the effective treatment of youth with a range of challenging symptoms. This paper provides a description of MBCT, including mindfulness practices, theoretical mechanisms of action, and targeted review of studies in adolescents.

Introduction

Many youths are at risk for experiencing stressors during adolescence that may lead to maladaptive coping strategies to manage negative affective experiences. Adolescence is a period of development and change for youth across multiple domains.Citation1 Although viewed by many as representing a dark and stormy period of emotional turbulence, most adolescents do not exhibit this pattern. However, epidemiological studies identify the adolescent years as conferring risk for internalizing problems of depression and anxiety for a minority of youth,Citation1,Citation2 as well as introducing the increased potential for sensation seeking and experimentation compared to younger children. Peers take on new social salience as teens increasingly reflect on their status in the interpersonal landscape, and social contextual consideration likely influences adolescents’ decisions when in the company of other youth. The interest in exciting emotional experiences and the affordances of social standing bring youth into contact with new types of stressors not previously experienced during childhood. While emotion regulation and coping may protect youth by mitigating the negative effects of stressors,Citation1,Citation3,Citation4 chronic exposure to stressors may deplete their coping resources. Significant, recurrent, and/or ongoing stress may contribute to toxic stress, in which an individual’s ability to manage or cope with stress is overwhelmed.Citation5 Increasingly, there are calls for broader thinking about how to mitigate the maladaptive aspects of stress experienced in the teen years to reduce the risk for long-term difficulties. Mindfulness-based treatments may provide a beneficial approach to help many adolescents reduce stress and other psychological problems. In this paper, we will review the history of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), literature pertaining to stress and coping experienced among youth, and evidence of its effectiveness with adolescents.

History of MBCT

Mindfulness has been defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally”.Citation6 Mindfulness instruction is intended to enhance awareness of and attunement to what is happening internally and externally with friendly curiosity and without judgment. The nonjudgmental awareness that is enhanced in mindfulness interventions is theorized to facilitate self-regulatory processes and coping, particularly during stressful experiences.Citation7 Therefore, mindful interventions may be helpful in alleviating suffering among youth dealing with life stress.

Mindfulness instruction includes exercises and techniques that cultivate an intentional focus on present-moment experience without being self-critical or judgmental. The goal of this trainingCitation6,Citation7 is to help individuals accept unpleasant and painful experiences without attempting to change the experience.Citation8 However, reducing or eliminating pain and discomfort is an understandable and natural tendency, so many mindfulness-based programs adopt a position of balancing the desire for change with an acceptance of the reality of uncomfortable experiences.Citation8

The use of mindfulness meditation practices to reduce distress has been a feature of many Eastern philosophical traditions (eg, Buddhism) for hundreds of years,Citation9 and have been increasingly used in Western medicine for well over 30 years.Citation10–Citation12 Meditation practices emerged from a body of Buddhist and other contemplative traditions that represent a complementary approach that joins psychological approaches to reduce stress and discomfort,Citation13 including cognitive–behavioral therapies and relaxation techniques. These approaches emphasize the importance of mindful acceptance and behavioral change as core processes to ameliorate mental and physical suffering. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was developed for use in adults suffering with chronic pain and ongoing stressors.Citation9–Citation11 Since the establishment of MBSR in 1979, several mindfulness-based interventions have been implemented to address a variety of psychological problems among adults,Citation12 including MBCT,Citation13 dialectical behavior therapy,Citation14 acceptance and commitment therapy,Citation15 and mindfulness-based relapse prevention.Citation16

MBSR was developed at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center and is an 8–10 week program consisting of 2½ hour sessions per week. The intervention is group-based, and participants are expected to commit to regular daily practice during program participation.Citation9 The program content focuses on mindfulness meditation practice, self-awareness of the body, yoga, and addresses barriers to the use of mindfulness practices during stressful moments.

Since the introduction of MBSR in 1979, several other psychological treatments emphasizing mindfulness and mindful acceptance have emerged within the behavioral and cognitive–behavioral movement. A common theme among these approaches was a new focus on affect and emotional experiences as a primary target for treatment. For example, dialectical behavior therapy incorporates mindfulness and acceptance practices to address severe emotional dysregulation.Citation14 Acceptance and commitment therapy focuses on the importance of the function and context of experiential avoidance to improve psychological flexibility.Citation17 MBCTCitation18 modified cognitive therapy to incorporate mindfulness techniques with the express purposes of training strategic attention deployment, particularly among adults with recurrent depression. Mindfulness-based approaches are distinguished from other cognitive–behavioral treatments in that cognitive behavioral therapy approaches focus on changing one’s thoughts and behavior while mindfulness-based approaches focus on balancing desire for changed experiences with acceptance of the present moment.

The format of MBCT mirrors the practices and approach of MBSR. The core MBSR curriculum forms the basis of MBCT, including formal exercises (eg, the raisin exercise, body scan, sitting meditation) and informal meditation in daily life (eg, washing dishes, brushing one’s teeth, taking out the trash). MBCT for individuals with a history of depression focuses the didactic portion of the course on depression specifically, rather than stress more generally. A key similarity is the emphasis on experiential exercises. Both MBSR and MBCT emphasize that instructors must have their own mindfulness practice and ongoing professional development to maintain adequate practice in order to support the accurate teaching of mindfulness exercises to others; both approaches also emphasize the importance of participant practice, both in group and at home, to facilitate the psychological changes theoretically associated with mindfulness training. From the cognitive perspective of MBCT, home-based meditation sessions are important not only to reinforce habits, but also to acquire new memories of nondepressogenic coping schemas.Citation18 Regardless of the actual mechanism, ongoing mindfulness practice ensures familiarity with the techniques that are presumed to improve self-regulation, likely through a variety of channels.

MBCT initially emerged as an effort to reduce the risk for depressive episodes by targeting maladaptive mood regulation. In the two decades since its introduction, MBCT has been extended to multiple applications for adults, including generalized anxiety disorder, treatment-resistant depressive disorder, cancer, suicidal behavior, and bipolar disorder.Citation19 Most of the research has been conducted with adult samples, with a much smaller research base with adolescents. We will next review the role of stress in adolescence, potential mechanisms of mindfulness in MBCT, and then finally review the evidence for MBCT in adolescents.

Review of literature

Stress exposure in youth

Stressors experienced in childhood and adolescence have been associated with maladaptive outcomes, including internalizing problems, externalizing behaviors, academic difficulties, and health risk behaviors.Citation20,Citation21 Exposure to some stressors increases as youth age into adolescence.Citation22 This picture is compounded with concern for minority youth, particularly those living in low-resource neighborhoods, who encounter a disproportionate share of stressors due to structural inequality.Citation23,Citation24 Minority youth are more likely to experience the death of a family member or friend, to have a relative with negative legal encounters (eg, arrested or jailed), to have to become a caretaker, and to be placed in the foster care system.Citation24,Citation25 Nevertheless, the effects of stress on coping and psychological functioning are important for all youth, as recurrent stressors may continuously tax an adolescent’s native self-regulatory system. As recent work has shown that coping can temper the effects of stress on development of depressive symptoms over time in youth,Citation24,Citation26 interventions that enhance adolescents’ abilities to cope effectively with inevitable stress may provide a protective effect against psychological difficulties.

Exposure to stressors may increase the risk for developing emotional and behavioral problems, particularly if youth rely on maladaptive coping and emotion regulation strategies. Many stressful circumstances are difficult to change, and negative thoughts associated with these stressors may be quite valid and accurately reflect genuinely negative experiences. Rumination is a process that has been implicated in depressive disorders,Citation27 and has been shown to increase the risk for recurrence and may respond favorably to MBCT.Citation28 Mindfulness-based interventions target the emotional and attentional processes associated with stress and may support the development of adolescents’ self-regulation. In the next section, we will review theoretical models that further detail how mindfulness-based treatments may reduce the negative effects of stress and highlight empirically evaluated mindfulness treatments for adolescents.

Effects of mindfulness on self-regulation

Mindfulness has been broadly theorized to improve self-regulation of emotions, behavior, and cognitive processes.Citation29 Emotion regulation is regarded as a fundamental aspect of many kinds of youth psychopathology generallyCitation30 and a potential mediator of the relationship between exposure to risk and healthy developmental outcomes for minority youth.Citation5 Self-regulation of negative emotions,Citation31 such as anger and sadness, is related to social and peer acceptance across childhood and adolescence; thus, in addition to psychological benefits, mindfulness approaches may improve emotion regulation which may, in turn, enhance social development.Citation32–Citation34 The psychological shift theorized to occur with mindfulness may contribute to improvements in associated cognitive, emotional, social, and behavioral domains (see for examples). Cognitive information-processing models have been useful in explaining mindfulness mechanisms. In one of their earliest papers introducing the theoretical foundation for MBCT, Teasdale et al explain that “‘central engine resources’ are devoted to repetitive, ‘ruminative,’ information processing cycles motivated to the attainment of central personal goals, or intentions, that can be neither attained nor relinquished”.Citation18 The inability to strategically direct one’s attention denotes a critical element of one’s cognitive processing resources and is theoretically constrained here by emotional considerations of attachment to a particular outcome in a complex matrix of individual goals and desires. We have previously discussedCitation7 the multiple ways by which an information-processing modelCitation18,Citation35 might explain how mindfulness works to modify attentional and emotional self-regulation processes: 1) interrupting automatic, “mindless” habits and cognitive scripts associated with maladaptive behavior; 2) changing an individual’s relationship to his or her own memory activation (eg, neutrally observing a memory, rather than attempting to inhibit it, or reacting in an emotionally negative way); 3) becoming desensitized to previous emotional triggers for behavior; and 4) developing increased attention to and awareness of one’s own general cognitive and emotional processes. Therefore, mindfulness “may change automatic response tendencies when the patient observes, describes, and participates in emotional experiences without acting on them”.Citation36 Likewise, mindfulness may help reduce ineffective action tendencies that are linked with emotion dysregulation,Citation36 and the reduction of inflexibility and avoidance may allow individuals to observe their psychological experiences instead of attempting to control them.Citation37

Table 1 Potential psychological changes associated with mindfulness training

Mindfulness approaches are theorized to result in improved self-regulation that emerges from increased acceptance and self-awareness, such as noticing unpleasant emotions and distress as experiences that can be accepted, rather than impulsively reacted to, ruminated over, or chronically avoided in an ineffective manner.Citation7,Citation13,Citation37,Citation38 An enhanced acceptance of internal experiences may decrease suffering and distress in response to stress. Mindfulness-based treatment may decrease symptoms through exposure to emotional and psychological stimuli, reduce maladaptive cognitive processes that inadvertently maintain negative mood states, change attitude/cognitive stance, and increase self-regulation and coping skills that promote acceptance.Citation13 Therefore, mindfulness may address maladaptive self-soothing and avoidant responses which function to maintain homeostasis that may accompany many forms of psychological disorders, including anxiety, depression, inattention, and other forms of psychopathology.

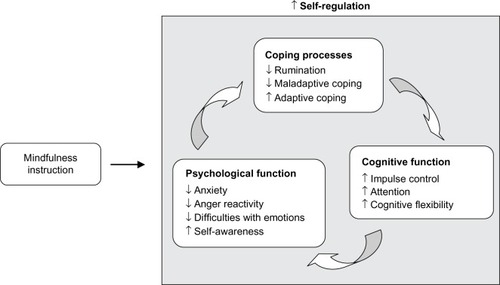

In summary, mindfulness approaches emphasize approaching and accepting one’s experiences, rather than the chronic efforts in avoiding uncomfortable or undesired experiences.Citation15 Our theoretical model () reflects the range of potential changes associated with mindfulness instruction, including the intertwined self-regulatory processes of improved coping, positive cognitive changes, and improved psychological functioning.

Figure 1 Mindfulness instruction and improved self-regulation.

Mindfulness-based therapies: empirical evidence

Studies of mindfulness-based interventions for use with youth and adolescents are still emerging. This growing literature provides preliminary evidence in support of the feasibility and benefits of mindfulness-based treatments for use in pediatric populationsCitation39–Citation41 and well-accepted by youth.Citation42,Citation43 Several mindfulness programs, including MBCT, have been adapted for use with youth. Adaptations include shorter practice periods when introducing formal mindfulness techniques and gradual increase in duration as the course progresses; making language appropriate for youth; and selecting age-appropriate mindfulness activities.Citation44 Our review of MBCT among adolescents will focus on identifying the effects and then suggesting areas for ongoing research.

In contrast to the adult literature, there are fewer empirical articles evaluating the effects of mindfulness training for youth. However, this growing body of knowledge has provided encouraging preliminary results regarding acceptability and feasibility in pediatric samples, suggesting that there is a continued need for more rigorous research on mindfulness program effects.Citation45 Moreover, several of these studies document positive changes in response to these mindfulness interventions. For example, mindfulness instruction in high school students led to improved blood pressure.Citation46 A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing mindfulness with hatha yoga and waitlist control showed that only mindfulness led to a significant improvement in working memory capacity.Citation47 Another RCT of disordered eating prevention for adolescent girls showed benefit when mindfulness was delivered in optimal facilitation,Citation48 suggesting that program delivery elements are important considerations of potential effect. Given the importance of MBSR in the original development of MBCT, we will review existing studies on MBSR in adolescents as well as MBCT.

Several studies have examined MBSR adapted for youth, showing feasibility, acceptability, and positive effects. Studies of MBSR from our program in an urban outpatient primary care clinic have demonstrated acceptability, feasibility, and potential benefit related to improved relationships and coping, and reduced conflict engagement, anxiety, and stress.Citation44,Citation49,Citation50 Furthermore, a small RCT of MBSR for urban youth aged 13–21 recruited from a primary care pediatric clinic demonstrated that MBSR could be feasibly and acceptably adapted for urban youth.Citation42 Qualitative data suggested that youth from the adapted MBSR program perceived improved self-regulation following instruction in mindfulness, including increased feelings of calm, self-awareness, and conflict avoidance, compared with youth in the active control program. Another RCT of MBSR compared with an active control program focused on boys in an urban school setting and documented decreased anxiety and rumination, with a trend for reduced negative coping and possible attenuation of cortisol response over the academic year.Citation43 An RCT of MBSR compared with an active control program (health education) for human immunodeficiency virus-positive, predominantly African-American youth found improvements in both self-regulation and physiological outcomes, with MBSR participants being more likely to have lower human immunodeficiency virus viral loads at 4–6 months follow-up compared to the control group.Citation51 Although these studies are small, they demonstrate that mindfulness-based therapies can be successfully adapted for use with youth and have a positive effect compared with an active control program. A larger RCT compared a school-based MBSR program for primary prevention with an active control program in two urban public schools (N=300). This trial showed that MBSR participants had statistically significant reductions in symptoms of depression, negative coping, negative affect, somatization, self-hostility, and posttraumatic stress symptoms.Citation52 Other trials of MBSR are promising as well. MBSR was compared with usual care for adolescents in outpatient psychiatric treatment using an RCT design and showed significantly reduced anxiety and depression and improvements in global psychiatric functioning.Citation53 In a treatment study of adolescent substance use,Citation54 MBSR was chosen as an effective complement to other therapeutic components (ie, sleep hygiene, stimulus control, and cognitive therapy) in reducing sleep problems and was well accepted. Taken together, these results are promising; yet, all of these studies underscore the need for rigorous study designs to enhance the methodological evaluation of mindfulness instruction for youth.

Fewer studies address the effects of MBCT programs for adolescents. MBCT has been modified for children as a downward extension of manualized MBCT.Citation55 Adaptations were based on developmental considerations to optimize the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention with youth. Key adaptations include shorter, more repetitious sessions (eg, 90 minutes instead of 2 hours, delivered over 12 weeks instead of 8 weeks); smaller groups (eg, six to eight students to two instructors, versus 30 adult participants in a group); use of formal limit-setting to prevent misbehavior (eg, review of rules); use of multisensory mindfulness experiences to address the cognitive capacity of this age group; use of incentives for session attendance and completion of homework (eg, stickers); and family involvement (eg, having parents support a child’s home practice, and encouraging mindful speech and behaviors at home). A small feasibility trial of MBCT adapted for children (MBCT-C) showed good acceptability and reduced internalizing (eg, anxiety, depression) and externalizing symptoms (eg, disruptive behavior) among a community sample of pre- and early adolescents, aged 9–12 years, with a history of academic problems.Citation55 Another trial of MBCT-C examined youth 9–13 years old and found reductions in attention problems.Citation56 This group had been referred for reading difficulties (84% ethnic minority); students were randomized to MBCT-C by age cohort (ie, 9–10 year olds or 11–13 year olds) or to a waitlist prior to participating in a future MBCT-C group. In addition, a strong association between attention problems and behavior problems was noted and the authors speculated that MBCT-C could help promote improved behavioral functioning by reducing inattention.Citation56

MBCT has been investigated in a group of adolescents with externalizing behavior problems in the Netherlands;Citation57 youth had diagnoses of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder, or autism spectrum disorder. This adaptation for adolescents and their parents was based on the original MBCT manual and used the same sequence of mindfulness activities (eg, body scan, mindful breathing, breathing space). Adolescents (N=14) and parents attended separate groups for 1.5 hours simultaneously; the group of adolescents focused on their difficulties, and the group of parents emphasized their role as a parent, including acceptance of their adolescent child, difficulties in communication, and family interactions. Attendance to group sessions was incentivized; adolescent participants earned points that could be exchanged for material and social rewards from parents, and they could earn money for completing the course. Postgroup analyses indicated improvement in adolescent attention, self-control, and mindful awareness; adolescents also reported decreased externalizing symptoms and social problems.

A more recently published study of MBCT in youth examined adolescents with ADHD in Canada.Citation58 Adolescents were 13–18 years old and 78% had comorbid psychiatric disorders. Teens and their parents (N=18) attended separate weekly sessions of 90 minutes for 8 weeks. The MYmind program is based on MBCTCitation12 and was developed by Bogels and colleagues in the Netherlands. Didactic content focused on mindfulness instruction as a useful tool for coping with ADHD symptoms, stress, family interactions, and difficult emotions. Results indicated reduced inattention, conduct problems, and peer problems following MBCT. Parents also reported reduced parenting stress and increased mindful parenting. In light of the good retention shown in this study, as well as the encouraging results, the MYmind curriculum is a promising adaptation of MBCT for adolescents with ADHD and other externalizing disorders.

Finally, one study has examined MBCT for adolescents with depression.Citation59 In this study, adolescents (N=11) aged 12–18 years with residual symptoms of depression following treatment were recruited to receive adapted MBCT. The MBCT approach was based on manualized adult MBCT as well as the modified MBCT-C adaptation; there were 8 weekly groups, and adolescent participants indicated high levels of satisfaction with the group intervention. Attendance rates were good, with 64% completing the course. Nearly all the participants were female. The small sample size limited analyses of potential treatment effects, but there were large effect sizes observed for changes in depressive symptoms and impact of symptoms, and more modest decreases in worry and rumination, and in improved quality of life. Thus, paralleling the extensive research base on MBCT for adults with a history of depression, this preliminary investigation would suggest that mindfulness instruction for adolescents could be a promising approach to reduce depressive symptoms.

In summary, evidence suggests that MBCT may be beneficial for adolescents and their parents to enhance self-regulation and coping. The results are encouraging, but the small sample sizes and lack of rigorous designs call for further research to clarify the extent and magnitude of the potential benefit for other groups of adolescents. Existing shortcomings of the studies examined here include: low number of participants; lack of a control group; limited follow-up period; and variable populations examined, including those without a formal psychiatric diagnosis. There is not currently a standard adolescent MBCT adaptation, which may make it difficult to compare across trials of various versions of modified MBCT with adolescents.

Recommendations for future research and clinical care

Mindfulness-based treatment approaches have been shown to improve overall well-being.Citation7 Mindfulness may enhance self-regulation and the reciprocal processes of cognitive functioning (eg, attentional deployment), psychological functioning (eg, emotional states), and coping (eg, responses to emotional challenge) (). Mindfulness-based approaches reduce psychological symptoms, improve emotion regulation, improve attention and the ability to focus, and reduce maladaptive coping and rumination.Citation7 These improvements are further associated with increased calmness, improved relationships, and reduced stress. While there is a great enthusiasm among many who study mindfulness instruction for youth and optimism for the benefits that mindfulness practices may yield, there is still a need for rigorous scientific evaluation of mindfulness interventions for adolescents.

Future research on mindfulness-based interventions for adolescents should prioritize improving the methods for evaluating mindfulness instructions to ensure that children and youth have access to optimal clinical care that is evidence based. MBCT has demonstrated a wealth of benefit among adults, but has not been tested as frequently or as rigorously among youth. Mindfulness interventions, including MBCT, need to be evidence based, and dissemination of these interventions needs to ensure fidelity. As with other efforts to disseminate treatments that have demonstrated efficacy, it will be crucial to determine how MBCT can survive the transfer from adults to adolescents, and then from optimal delivery in rigorous studies to more typical settings of care, such as community mental health centers. The application of implementation science to efforts to disseminate mindfulness instruction by MBCT will play a critical role in the success of delivering high-quality mindfulness programming. Second, future research needs to continue to identify the potential mechanisms of change associated with mindfulness instruction. When MBCT demonstrates positive changes for youth, it will continue to be important to identify which emotional and psychological processes are changed (eg, attentional processes, rumination, reappraisal) and how they are improved.

Mindfulness techniques represent a group of complementary treatments that are beneficial for youth presenting with a range of behavioral, emotional, and somatic symptoms, as mindfulness instructions change the relationship to one’s experiences in a positive way. Encouraging mindful awareness of one’s present-moment experiences, as well as associated thoughts and emotions, allows an individual to recognize both the sensation and responses to the stimulus. As a result, individuals decrease attachment to the associated thoughts and emotions, which enables more flexible responding to stress and psychological symptoms.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PausTKeshavanMGieddJNWhy do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence?Nat Rev Neurosci200891294795719002191

- KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOJinRMerikangasKRWaltersEELifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry200562659360215939837

- GieddJNBlumenthalJJeffriesNOBrain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI studyNat Neurosci199921086186310491603

- SpearLPThe adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestationsNeurosci Biobehav Rev200024441746310817843

- LazarusRSFolkmanSStress, Appraisal, and CopingNew York, NYSpringer1984

- Kabat-ZinnJWherever you Go, There you areNew York, NYHyperion1994

- Perry-ParrishCKSibingaEMSMindfulness meditation for childrenAnbarRDFunctional Symptoms in Pediatric Disease: A Clinical GuideNew York, NYSpringer2014343352

- O’BrienKMLarsonCMMurrellARThird-wave behavior therapies for children and adolescents: Progress challenges, and future directionsGrecoLAHayesSCAcceptance and Mindfulness Treatments for Children and Adolescents: A Practitioner’s GuideOakland, CANew Harbinger Publications20041535

- Kabat-ZinnJFull Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and IllnessNew York, NYBantam Books1990

- Kabat-ZinnJAn outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary resultsGen Hosp Psychiatry19824133477042457

- Kabat-ZinnJLipworthLBurneyRThe clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic painJ Behav Med1985821631903897551

- BaerRAMindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical reviewClin Psychol2003102125143

- SegalZVWilliamsJGTeasdaleJDMindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing RelapseNew York, NYGuilford Press2002

- LinehanMMCognitive-behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality DisorderNew York, NYGuilford Press1993

- HayesSCStrosahlKDA Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment TherapyNew York, NYSpringer Science + Business Media2004

- WitkiewitzKMarlattGAWalkerDMindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance use disordersJ Cogn Psychother2005193211228

- HayesSCWilsonKGAcceptance and commitment therapy: Altering the verbal support for experiential avoidanceBehav Anal199417228930322478193

- TeasdaleJDSegalZWilliamsJGHow does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help?Behav Res Ther199533125397872934

- TeasdaleJDSegalZWilliamsJGRidgewayVASoulsbyJMLauMAPrevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapyJ Consult Clin Psychol200068461562310965637

- BurkeCAMindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent fieldJ Child Fam Stud201010133144

- GrantKCompasBThurmAStressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Evidence of moderating and mediating effectsClin Psychol Rev200626325728316364522

- LambertSCopeland-LinderNIalongoNLongitudinal associations between community violence exposure and suicidalityJ Adolesc Health200843438038618809136

- BroderickPCJenningsPAMindfulness for adolescents: A promising approach to supporting emotion regulation and preventing risky behaviorMaltiTAdolescent Emotions: Development, Morality, and AdaptationSan Francisco, CAJossey-Bass2013111126

- Garcia CollCLambertyGJenkinsRAn integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority childrenChild Dev1996675189119149022222

- Perry-ParrishCCopeland-LinderNWebbLSibingaEMindfulness-based therapiesBreland-NobleAAl-MateenCSinghNHandbook of Mental Health in African American Youth1st edNew York, NYSpringer201691105

- KilmerRCowenEWymanPWorkWMagnusKDifferences in stressors experienced by urban African American, White, and Hispanic childrenJ Community Psychol1998265415428

- EvansLDKourosCFrankelSALongitudinal relations between stress and depressive symptoms in youth: Coping as a mediatorJ Abnorm Child Psychol201543235536824993312

- Nolen-HoeksemaSThe role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptomsJ Abnorm Psychol2000109350451111016119

- JimenezSSNilesBLParkCLA mindfulness model of affect regulation and depressive symptoms: Positive emotions, mood regulation expectancies, and self-acceptance as regulatory mechanismsPers Individ Dif2010496645650

- FrickPJMorrisASTemperament and developmental pathways to conduct problemsJ Clin Child Adolesc Psychol2004331546815028541

- ZemanJCassanoMPerry-ParrishCStegallSEmotion regulation in children and adolescentsJ Dev Behav Pediatr20062715516816682883

- Perry-ParrishCZemanJRelations among sadness regulation, peer acceptance, and social functioning in early adolescence: The role of genderSoc Dev201120135153

- Perry-ParrishCWebbLZemanJAnger regulation and social acceptance in early adolescence: Associations with gender and ethnicityJ Early Adolesc2015

- Perry-ParrishCWaasdorpTBradshawCPeer nominations of emotional expressivity among urban children: Social and psychological correlatesSoc Dev20112118810822350560

- BreslinFCZackMMcMainSAn information-processing analysis of mindfulness: Implications for relapse prevention in the treatment of substance abuseClin Psychol200293275299

- LynchTRChapmanALRosenthalMZKuoJRLinehanMMMechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therapy: Theoretical and empirical observationsJ Clin Psychol200662445948016470714

- KavanaghDJAndradeJMayJBeating the urge: Implications of research into substance-related desiresAddict Behav20042971359137215345270

- WilliamsMTeasdaleJSegalZKabat-ZinnJThe Mindful Way through Depression: Freeing Yourself from Chronic UnhappinessNew York, NYGuilford Press2007

- SibingaESKemperKJComplementary, holistic, and integrative medicine: Meditation practices for pediatric healthPediatr Rev201031129110320194901

- MeiklejohnJPhillipsCFreedmanMLIntegrating mindfulness training into K-12 education: Fostering the resilience of teachers and studentsMindfulness201234291307

- ZoogmanSGoldbergSBHoytWTMillerLMindfulness interventions with youth: A meta-analysisMindfulness201462290302

- SibingaEMSPerry-ParrishCThorpeKMikaMEllenJMA small mixed-method RCT of mindfulness instruction for urban youthExplore201410318018624767265

- SibingaESPerry-ParrishCChungSJohnsonSBSmithMEllenJMSchool-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: A small randomized controlled trialPrev Med201357679980124029559

- SibingaESKerriganDStewartMJohnsonKMagyariTEllenJMMindfulness-based stress reduction for urban youthJ Altern Complement Med201117321321821348798

- TanLBA critical review of adolescent mindfulness-based programmesClin Child Psychol Psychiatry201621219320725810416

- BarnesVATreiberFAJohnsonMHImpact of transcendental meditation on ambulatory blood pressure in African-American adolescentsAm J Hypertens200417436636915062892

- QuachDJastrowski ManoKEAlexanderKA randomized controlled trial examining the effect of mindfulness meditation on working memory capacity in adolescentsJ Adolesc Health201658548949626576819

- AtkinsonMJWadeTDMindfulness-based prevention for eating disorders: A school-based cluster randomized controlled studyInt J Eat Disord20154871024103726052831

- SibingaEMStewartMMagyariTWelshCKHuttonNEllenJMMindfulness-based stress reduction for HIV-infected youth: A pilot studyExplore200841363718194789

- KerriganDJohnsonKStewartMPerceptions, experiences, and shifts in perspective occurring among urban youth participating in a mindfulness-based stress reduction programComplement Ther Clin Pract20111729610121457899

- WebbLGhazarianSPerry-ParrishCEllenJSibingaEMindfulness instruction for urban, HIV-positive youth: A small randomized controlled trialJ Early Adolesc Epub20151028

- SibingaEMWebbLGhazarianSREllenJMSchool-based mindfulness instruction: an RCTPediatrics2016137118

- BiegelGMBrownKWShapiroSLSchubertCMMindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trialJ Consult Clin Psychol200977585586619803566

- BootzinRRStevensSJAdolescents, substance abuse, and the treatment of insomnia and daytime sleepinessClin Psychol Rev200525562964415953666

- LeeJSempleRJRosaDMillerLMindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Results of a pilot studyJ Cogn Psychother20082211528

- SempleRJLeeJRosaDMillerLFA randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Promoting mindful attention to enhance social-emotional resiliency in childrenJ Child Fam Stud2010192218229

- BögelsSHoogstadBvan DunLde SchutterSRestifoKMindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parentsBehav Cogn Psychoth200836193209

- HaydickyJShecterCWienerJDucharmeJMEvaluation of MBCT for adolescents with ADHD and their parents: Impact on individual and family functioningJ Child Fam Stud2015247694

- AmesCSRichardsonJPayneSSmithPLeighEInnovations in practice: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression in adolescentsChild Adolesc Ment Health2014197478