Abstract

Struggling medical trainees pose a challenge to clinical teachers, since these learners warrant closer supervision that is time-consuming and competes with time spent on patient care. Clinical teachers’ perception that they are ill equipped to address learners’ difficulties efficiently may lead to delays or even lack of remediation for these learners. Because of the paucity of evidence to guide best practices in remediation, the best approach to guide clinical teachers in the field remains to be established. We aimed to present a synthetic review of the empirical evidence and theory that may guide clinical teachers in their daily task of supervising struggling learners, reviewing current knowledge on the challenges and solutions that have been identified and explored. A computerized literature search was performed using Medline, Embase, Education Resources Information Center, and Education Source, after which final articles were selected based on relevance. The literature reviewed provided best evidence for clinical teachers to address learners’ difficulties, which is presented in the order of the four steps inherent to the clinical approach: 1) detecting a problem based on a subjective impression, 2) gathering and documenting objective data, 3) assessing data to make a diagnosis, and 4) planning remediation. A synthesized classification of pedagogical diagnoses is also presented. This review provides an outline of practical recommendations regarding the supervision and management of struggling learners up to the remediation phase. Our findings suggest that future research and faculty development endeavors should aim to operationalize remediation strategies further in response to specific diagnoses, and to make these processes more accessible to clinical teachers in the field.

Introduction

Clinical teachers are faced with the daily challenge of managing patients while simultaneously supervising medical trainees from all levels of training and with varying degrees of autonomy.Citation1 Steinert has defined struggling learners as medical trainees who do “not meet the expectations of a training program”.Citation2 Such trainees, who experience more difficulties, often pose an even greater challenge to clinical teachers, since these learners warrant closer supervision,Citation3 which may be time-consuming and compete with time spent on patient care, but may also require specific teaching skills.Citation4 As a result, the supervision of struggling learners has been associated with reactions from clinical teachers ranging from helplessness to frustration and avoidance,Citation2,Citation5 as clinical teachers often perceive that they are ill equipped to supervise these learners efficiently.Citation6

The discomfort that clinical teachers may feel when supervising struggling learners may have concrete consequences for learners and patients alike. Clinical teachers in the field are often best positioned to detect difficulties early on, due to their privileged access to learners’ actual performances with real patients, and to the fact that struggling learners very rarely step forward themselves to ask for help.Citation7 When difficulties are not addressed as soon as they are detected, undue delays might occur before remediation and closer follow-up can take place.Citation8,Citation9 In certain cases, learners’ difficulties may in fact never be addressed, which may eventually allow less than fully competent trainees to be promoted to independent practice.Citation10–Citation12

Although clearly delineated guidelines for supervising struggling learners could offer a useful solution to these issues, no such guidelines exist, due to the paucity of evidence to guide best practices in remediation.Citation9,Citation13 Intervention studies regarding remediation have often been limited to small single-institution endeavors, and have focused on the remediation of cognitive difficulties.Citation9,Citation14 Although recommendations for remediation at an institutional level have recently been published,Citation15 the best approach for clinical teachers in the field remains to be established.

Therefore, we aimed to present here a synthetic review of the empirical evidence and theory that may guide clinical teachers in their daily task of supervising struggling learners. This article reviews our current knowledge on the challenges and solutions that have been identified and explored.

Materials and methods

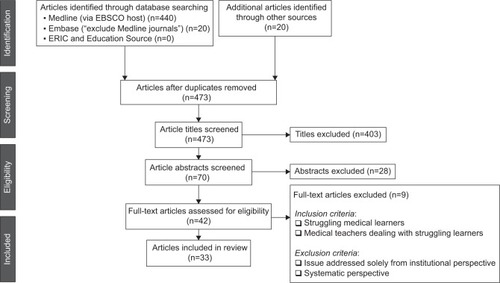

Our methodology was based on Grant and Booth’sCitation16 typology of reviews, which defines a literature review as the “examination of recent or current literature”, whose “analysis may be conceptual or thematic” and is “typically narrative”. A search of the relevant literature was performed in both medical (Medline, Embase) and educational (ERIC, Education Source) databases, using the following search terms: underperformance, fail, at risk, difficult or problem, combined with clinical or medical student or resident. The search covered the 1995–2015 period, and was limited to the English and French languages. This search strategy generated 440 titles. After an initial title-based screening, 70 abstracts were read, of which 37 were rejected based on relevance. A total of 33 articles were thus included in this review ().

Articles were considered for inclusion if they addressed the issue of struggling learners from the perspective of medical teachers in the field, or if they presented empirical evidence or theory that could inform their perspective. Because this review focused on clinical teachers’ daily supervision tasks, articles that addressed the issues of learner difficulties solely from an institutional or systematic perspective were excluded. A meta-analysis was not deemed feasible, due to the wide variety of research contexts and methodologies encompassed, nor was an exhaustive review the purpose of this article. Rather, it aimed to synthesize the most relevant concepts to guide clinical teachers when working with struggling learners.

Results

Theoretical framework

A theoretical framework for addressing struggling medical trainees was provided by Langlois and Thach,Citation17 who first suggested that the SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) clinical model could be used to structure the approach to learners with difficulties. This model has since been used repeatedly in medical education.Citation18–Citation20 It takes advantage of the parallel often drawn, since IrbyCitation21 pointed it out, between the clinical and pedagogical diagnostic approaches.Citation1,Citation22–Citation24 When applied to struggling learners, the SOAP model divides the task into four steps that are well known to clinicians: 1) detecting problems, based on a subjective impression; 2) gathering and documenting objective data, according to diagnostic hypotheses; 3) making a pedagogical diagnosis based on this assessment; and 4) planning a targeted remediation. These steps can guide clinical teachers to approach learners’ difficulties in the same order that they assess patient symptoms. In this review, the relevant literature and recommendations () are also organized as per these four main steps.

Table 1 Suggested approach to struggling learners

Subjective: Detecting a problem based on a subjective impression

Between 10% and 15% of learners will experience significant difficulties during their medical training.Citation25–Citation27 The various steps leading to their formal identification are most often initiated based on the subjective impressions of clinical teachers.Citation7 These subjective impressions, or intuitions, can be either shaped by direct observation of the learner in action or by interacting formally or informally with the student.Citation28 Clinical teachers’ perceptions are indeed considered to be a reliable predictor of learners’ difficulties. Weller et al,Citation3 for instance, found that when clinical teachers were asked to identify subjectively which learners required closer supervision, a reliability coefficient of 0.7 was reached with nine observers, whereas 50 observers were required to reach this same coefficient when more traditional measures were used.

In theory, clinical teachers’ recognition of difficulties in a learner should prompt the next steps of documentation, assessment, and remediation rapidly, since early identification is considered the gold standard to attain.Citation23 In practice, however, the process is very often halted at this stage.Citation2,Citation9,Citation18,Citation29,Citation30 One of the most frequently cited reasons for this, according to many exploratory studies done with clinical teachers, is the discomfort of not knowing which steps should be followed and how to achieve them.Citation6,Citation31–Citation33

The consequence of not acting on clinical teachers’ early impressions is the frequent delay in identifying and addressing learners’ difficulties. Late identification of difficulties was defined by LacasseCitation34 as identification that takes place after the first quarter of a rotation. When this occurs, practical implications are that less time is left for efficient remediation, but also that critical incidents may take place, with concrete consequences to patients, before a red flag is raised.Citation8,Citation28 A US survey of program directors in internal medicine in 2000 drove the point home by revealing that up to 59% of their residents in difficulty were indeed identified after a critical incident.Citation35 In order to avoid consequences associated with late identification of difficulties, and because their subjective impressions can be considered reliable, clinical teachers should be encouraged to act on their perceptions of difficulties in learners as soon as a doubt arises,Citation34 beginning with the gathering and documenting of objective data.

Objective: Gathering and documenting objective data

According to Bearman et al,Citation30 establishing a diagnosis in medical education consists in “identifying discrepancy between the expected performance standard and the demonstrated performance, and then trying to establish the reason for underperformance”. In many clinical programs, expected abilities at various stages of training are defined through milestones,Citation36 while key tasks in a discipline that learners should eventually be trusted to perform are defined as “entrustable” professional activities (EPAs).Citation37 Milestones and EPAs can both be very useful in identifying and documenting discrepancy. Once it is identified, however, underperformance should be seen as a symptom, not as a diagnosis in itself, which once made could justify ending the observation phase.Citation17,Citation34,Citation38 The first step in addressing difficulties should consist, on the contrary, in further observations to define the issue betterCitation28 and to clarify its cause better, in order to determine the most appropriate response.Citation18,Citation19 Further verification of the initial impression formed also helps determine whether the learner is in fact experiencing difficulties that require follow-up or whether the issue was contextual or even an isolated incident.Citation39

Through this collection of data, tangible examples must be gathered. This should be done as much for clinical teachers, who will thus verify their impressions, as for the learner, who is more likely to see credibility in the feedback received,Citation35 and for the institution, who will be able to justify its decisions better.Citation18,Citation34 Objective data are indeed an integral part of a fair approach.Citation28 According to many authors, this initial documentation is the responsibility of clinical teachers in the field, because only they have access to learners’ performances in a real clinical context.Citation30,Citation40,Citation41 The documentation of clinical performance by clinical teachers is essential, since only 2%–6% of struggling learners will self-identify.Citation7,Citation35 Various hypotheses have been put forward to explain why such low rates of learners will themselves ask for help. These hypotheses range from fear of academic and social consequencesCitation35 to self-appraisals, which are significantly different from actual performance.Citation42 Kruger and DunningCitation43 have indeed shown that those who are “unskilled” in a certain discipline are often unaware of it, because the same knowledge is often necessary to be both competent and have an accurate perception of one’s competence in a given field. For instance, participants in the Kruger and Dunning study whose test scores were in the 12th percentile estimated themselves to be in the 62nd percentile. These participants only recognized their errors once their skills had improved.

How to collect pedagogical data

Data collection can be achieved either through indirect or direct observation of learners’ performances. The latter occurs relatively rarely unless procedures or techniques are involved,Citation9,Citation44 but will often be more effective. In a national US survey of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine, a clear majority (82%) reported that problem-learner difficulties had been identified in their institution through direct observation.Citation35 Difficulties, however, can also be inferred from the manner in which cases are presented or from indirect observation,Citation45 but where indirect observation is the only type of observation, certain difficulties could be masked.Citation29 Data can also be collected by reviewing notes written by the learner in patient files or through their formal and informal interactions with staff and faculty. No matter which approach is preferred or available, data should always be based on more than one context and on as many observations as possible.Citation9,Citation46

Many observations are indeed necessary, due to the subjective nature of observations made in clinical settings, but also due to case specificity. As Nendaz et alCitation47 put it, the competence to diagnose varies from one case to another for the same clinician. It is thus more reliable to question a learner more briefly on many cases. For an observed behavior to lead to a diagnosis, it ought to have been observed repeatedlyCitation9 and in various types of situations. Indeed, each performance depends as much on the context as it depends on the content,Citation48 and hence Jouquan’s statementCitation49 that the nonmanifestation of a certain knowledge does not systematically equate with its absence [translation].

Hinson et alCitation50 stressed the importance of an additional source of data, which they called “diagnostic conversations”: these conversations consist of “discussing the problem and getting a fuller picture of everything that is going on for that student”. This conversation allows a more accurate pedagogical diagnosis, but may also bring to light potential gaps in perceptions, giving an opportunity for both parties to share the same understanding of a given situation.Citation34 The diagnostic conversation can henceforth be used as a common starting point, which will facilitate a shared appreciation of whether or not progress has been made later on.Citation30 When relevant, it will also allow the taking into account of the learner’s context and reality with regard to the remediation plan, allowing it to be more realistic and increasing the chance that it will be followed.Citation50 In fact, the reasons for the observed difficulties should be determined jointly with the learner, since only the learners hold the whole picture of their personal situation.Citation28,Citation30,Citation38 Faculty can only gain from adding this insider’s perspective to the outside perception of the learner’s professional performance. Diagnostic conversations can take the form of a brief exchange at the end of a shift or of a more substantial discussion in light of all the assembled information to date, but LacasseCitation34 recommends that at the very least, an informal discussion be held with the learners themselves before any further step is undertaken.

Assessment: Making a pedagogical diagnosis based on assessment of the collected data

Underperformance may be due to one of three main categories of difficulties – related to cognition, mental health, or attitude – among which cognitive difficulties are the most frequent.Citation27,Citation35,Citation51 When considering which category is most likely involved, it must be borne in mind that causes of under-performance are often interrelated.Citation34 A study by Guerrasio and Aagaard,Citation14 for instance, showed that among 53 learners followed for clinical reasoning difficulties, three-quarters had “comorbidities”, ranging from insufficient knowledge (17% of students) to mental health issues (12% of residents). In such cases, the best approach is to address difficulties one by one, beginning with the predominant difficulty for that learner or the one that interferes most with their work.

One prominent finding when reviewing the literature on the causes of underperformance to consider when a learner is in difficulty is the absence of consensus among authors on what the differential diagnosis should include and on how to classify it. Indeed, up to 17 different classification systems of underperformance have been identified in this review. They have been synthesized in one table for the purpose of this article, and are presented in . This striking disparity of classifications seems to be related to the disparity of sources used by each author to classify learner difficulties. Cited sources vary from regulating institutions, whose classification systems are based on expert consensusCitation7,Citation35,Citation52 to systematic reviewsCitation34,Citation53 to compilations of clinical teachers’ narrative descriptions.Citation51,Citation54,Citation55 In a few cases, no source was cited.Citation18,Citation22,Citation56,Citation57 This multitude of classification systems also stems from the fact that none of these systems was reused in its entirety by authors other than the original author. Rather, new classification systems were created each time by adapting or summarizing one or more preexisting classifications.Citation17,Citation19,Citation20,Citation58

Table 2 A synthesis of classification systems of underperformance in medical education

A quick look at the synthesis of these classification systems in reveals that among the main causes of underperformance that are cognitive in origin, a lack of knowledge is cited significantly more often than clinical reasoning difficulties. However, while insufficient knowledge is indeed much more prevalent among medical students in difficulty, clinical reasoning difficulties have been shown to be at least as frequent during residency.Citation7 The fact that its consideration as a cause of underperformance is so markedly less frequent (four authors of 17 cited it explicitly) could also suggest a lack of knowledge transfer from one research field to the other: although clinical reasoning has been the subject of 40 years of research, it may at times be confined to a debate among experts,Citation29 which may be partly due to the hermetic terminology used in cognitive psychology, as suggested by Kempainen et al.Citation59 Moreover, there seems to exist a misconception that clinical reasoning errors are driven by a lack of medical knowledge, rather than an inability to apply that knowledge in clinical practice.Citation60

Plan: Planning a targeted remediation

Remediation was defined by Guerrasio et alCitation7 as “additional teaching above and beyond the standard curriculum, individualized to the learner who without the additional teaching would not achieve the necessary skills for the profession”. As pointed out by Hauer et al’sCitation9 thematic review of the literature on remediation, no standardized and universally accepted remediation processes have yet been developed. Remediation initiatives will thus often resort to ad hoc and uncoordinated processesCitation27,Citation61 or to the sterile repetition of inconclusive strategies.Citation30,Citation62–Citation64 One possible cause for the absence of a standardized remediation process may very well be the aforementioned absence of consensus on the specific causes of underperformance. It is indeed much more difficult to solve a problem that has not been well defined, and the demonstrated disparity among classification systems of underperformance means that there exists at present no consensual basis on which to build common guidelines for managing difficulties.

In practice, obstacles to efficient remediation also arise when the pedagogical diagnosis has not been well established at the outset. Remediation may in fact be fruitless if the previous step, clarifying the diagnosis, has been overlooked.Citation28 Therefore, the first step in planning a targeted and efficient remediation is to have pinpointed the underlying issue as precisely as possible. This point cannot be overstressed, knowing that Bearman et alCitation30 have shown, consistent with our anecdotal experience, that the very idea of matching a remediation intervention with the underlying difficulty is rarely a consideration for clinical teachers in the field. This approach may lead, for instance, to simply adding a supplemental clinical rotation as a remediation strategy for issues related to professionalism. The lack of well-defined remediation strategies for clinical teachers in the field can only (understandably) deter them from naming difficulties that they would not know how to address. Therefore, there is a strong need for further research with regard to remediation that is evidence-based, individualized, and targeted according to pedagogical diagnosis.Citation2,Citation18,Citation35,Citation65,Citation66 In the absence of formal guidelines, however, some guiding principles may be drawn from previous studies on remediation.

In situ remediation

Whereas learners with noncognitive difficulties should be referred, it is generally recommended that cognitive difficulties first be addressed within the learners’ current rotations,Citation9,Citation18,Citation67 an approach that Bearman et alCitation30 termed “in situ learning”. Only if this approach fails should the issue be brought to the next institutional level. Remediation that is integrated with the learners’ usual clinical activities is generally regarded as the most efficient,Citation18,Citation30 because in situ remediation is based on the cognitive psychology principle of experiential learning. First, it allows the learner to anchor new knowledge to skills that are already mastered and to a context that is already familiar.Citation65 Second, it also allows this new knowledge to be contextualized and transferred immediately to an authentic practice setting.Citation68,Citation69 Finally, in situ remediation takes advantage of experiential learning by focusing the learning process on real-life issues that the learner truly has to solve.Citation34 Unfortunately, in practice, a survey conducted by Saxena et alCitation65 among 71 US medical schools showed this integrated form of remediation to be the least utilized, possibly (according to the same study) because of the lack of confidence clinical teachers often express regarding their own capacity for remediating learners’ difficulties.

Time-efficient remediation

The management of struggling learners is notorious – and sometimes dreaded – for being time-consuming.Citation7,Citation14,Citation20,Citation34,Citation61 In one study based on 151 medical learners with difficulties, Guerrasio et alCitation7 observed that the remediation of clinical reasoning difficulties was among the most time-consuming remediation processes, with an average of 20 hours spent on individual interventions per student. There is an obvious need for time-efficient remediation strategies, because for remediation activities to be realistically integrated with a regular rotation, it is crucial that these activities be time-efficient, as they will otherwise not be acceptable to clinical teachers.Citation70

Discussion

Our review has shown that many principles are well established regarding the approach to struggling medical learners. As presented in , an effective approach to the clinical supervision of struggling learners should aim for early and precise identification of difficulties, based on repeated observations and on an initial informal discussion with the learner. A pedagogical diagnosis should be made, supported by various sources of data, acknowledging that difficulties can be interrelated. Only once this pedagogical diagnosis is clear should a targeted remediation strategy be developed and ideally integrated with the learner’s regular clinical activities. This review has also shown, however, that there remain both theoretical and practical challenges to address, in order to operationalize these principles further. Three-pronged recommendations are discussed in response to these challenges.

Faculty development

Certain barriers to applying best practices in the field could be addressed by faculty-development endeavors. Firstly, a lack of proper documentation by clinical teachers has been identified as one of the main causes of failure. It has been suggested that this step may be omitted, because clinical teachers do not know what to observe and document specifically. Knowledge of key elements to document proof of competence in a learner, or lack thereof, should be made explicit to clinical teachers, in accordance with the expected development path at respective institutions. Secondly, the identification of precise pedagogical diagnoses to explain underperformance has repeatedly been identified by clinical teachers themselves as a pressing faculty-development need. Since the next practical steps will derive from these diagnoses, faculty support in identifying the underlying issues would be instrumental in helping clinical teachers carry through an effective approach to struggling learners.

Institutional procedures

This review has also pointed out some steps in the management of struggling learners, which if implemented locally as preset procedures could then serve as common references among faculty. We hypothesize that having a simple and preestablished procedure to which learners could be referred should foster earlier identification of struggling learners. In this perspective, the first process to formalize should be a comprehensive description of steps to follow when referring a learner for remediation. Such processes should be determined locally, based on best evidence in remediation and organized according to available resources. For instance, clinical teachers, as well as rotation supervisors, should know ahead who to notify, formally and informally, if an issue arises. It should be clear who is responsible for overseeing the remediation process, and who serves as faculty advisor for this purpose. A second procedure, which could be preestablished locally, is a list of relevant descriptors for clinical teachers to observe and document, in order to situate the learner effectively with regard to the expected level of competence. Such descriptors will generally be drawn from the milestones relevant to each level of training.

Further research

The absence of a common framework to organize learner difficulties and from which to build standardized remediation strategies has been highlighted in this review. The establishment of such a framework should be given priority, in order for future research to build around a common structure. This objective also appears as a preliminary step to address a second pressing need: that of developing and evaluating efficient remediation strategies on a wider scale. Such endeavors should focus on targeting remediation strategies according to diagnosis, hence the need for a common framework to build from, and should aim for them to be time-efficient, so as not to impede their implementation in practice.

Conclusion

This article aimed to review the theory and empirical evidence available regarding the global approach to struggling learners during clinical supervision. Our review has shown that the perception that a learner is experiencing difficulty is assessed intuitively and reliably by clinical teachers, but that their unfamiliarity with the following steps, from pedagogical diagnoses to remediation strategies, leads to delays before the formal identification of these learners. Because early identification of struggling learners should be considered a gold standard, the subsequent steps for clinical teachers have been presented here, organized around the clinical model SOAP. Many obstacles have been identified to their practical application, among which the lack of standardized remediation procedures is not a lesser deterrent. Is there a recipe for supervising struggling learners? The answer remains to be completed, and future research and faculty-development endeavors should pursue the common goal of further operationalizing remediation strategies in response to specific diagnoses and making these processes more accessible to clinical teachers in the field.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AudétatMCLaurinSClinicien et superviseur, même combat! [Clinician and supervisor, same battle!]Med Que20104555357 French

- SteinertYThe “problem” junior: whose problem is it?BMJ2008336763615015318202068

- WellerJMMisurMNicolsonSCan I leave the theatre? A key to more reliable workplace-based assessmentBr J Anaesth201411261083109124638231

- WalshAAntaoVBethuneCFundamental Teaching Activities in Family Medicine: A Framework for Faculty DevelopmentMississauga (ON)College of Family Physicians of Canada2015

- DoryVAudétatMC“Ils sont carrément incurables”: comment les métaphores des cliniciens enseignants révèlent leur malaise dans la gestion des difficultés de raisonnement clinique de leurs internes. [“They’re downright incurable”: how the metaphors clinical supervisors use reveal their unease at dealing with the clinical reasoning difficulties of their residents]Pedagog Med20131428397 French

- AudétatMCFaguyAJacquesABlaisJGCharlinBÉtude exploratoire des perceptions et pratiques de médecins cliniciens enseignants engagés dans une démarche de diagnostic et de remédiation des lacunes du raisonnement cliniquePedagog Med Exploratory study on the perceptions and practices of clinical teachers involved in a clinical-reasoning difficulty diagnosis and remediation process2011121716 French

- GuerrasioJGarrityMJAagaardEMLearner deficits and academic outcomes of medical students, residents, fellows, and attending physicians referred to a remediation program, 2006–2012Acad Med201489235235824362382

- ChallisMFlettABatstoneGAn accident waiting to happen? A case for medical educationMed Teach199921658258521281178

- HauerKECicconeAHenzelTRRemediation of the deficiencies of physicians across the continuum from medical school to practice: a thematic review of the literatureAcad Med200984121822183219940595

- DudekNLMarksMBRegehrGFailure to fail: the perspectives of clinical supervisorsAcad Med20058010 SupplS84S8716199466

- GuerrasioJFurfariKARosenthalLDNogarCLWrayKWAagaardEMFailure to fail: the institutional perspectiveMed Teach201436979980324845780

- Yepes-RiosMDudekNDuboyceRCurtisJAllardRJVarpioLThe failure to fail underperforming trainees in health professions education: a BEME systematic review – BEME Guide no. 42Med Teach201638111092109927602533

- ZiringDDanoffDGrossemanSHow do medical schools identify and remediate professionalism lapses in medical students? A study of U.S. and Canadian medical schoolsAcad Med201590791392025922920

- GuerrasioJAagaardEMMethods and outcomes for the remediation of clinical reasoningJ Gen Intern Med201429121607161425092006

- KaletAGuerrasioJChouCLTwelve tips for developing and maintaining a remediation program in medical educationMed Teach201638878779227049798

- GrantMJBoothAA typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologiesHealth Info Libr J20092629110819490148

- LangloisJPThachSManaging the difficult learning situationFam Med200032530730910820670

- Ronan-BentleSEAvegnoJHegartyCBMantheyDEDealing with the difficult student in emergency medicineInt J Emerg Med201143921714855

- VaughnLMBakerRCDeWittTGThe problem learnerTeach Learn Med1998104217222

- HicksPJCoxSMEspeyELTo the point – medical education reviews: dealing with student difficulties in the clinical settingAm J Obstet Gynecol200519361915192216325592

- IrbyDMWhat clinical teachers in medicine need to knowAcad Med19946953333428166912

- SteinertYLevittCWorking with the “problem” resident: guidelines for definition and interventionFam Med199325106276328288064

- EvansAlstead EMBrownJApplying your clinical skills to students and trainees in academic difficultyClin Teach20107423023521134196

- IrbyDMExcellence in clinical teaching: knowledge transformation and development requiredMed Educ201448877678425039734

- YatesJJamesDPredicting the “strugglers”: a case-control study of students at Nottingham University Medical SchoolBMJ200633275481009101316543299

- FaustinellaFOrlandoPRCollettiLAJunejaHSPerkowskiLCRemediation strategies and students’ clinical performanceMed Teach2004267664665

- SmithCSStevensNGServisMA general framework for approaching residents in difficultyFam Med200739533133617476606

- SteinertYThe “problem” learner: whose problem is it? AMEE Guide no. 76Med Teach2013354e1035e104523496125

- AudétatMCL’identification et la remédiation des difficultés de raisonnement clinique en médecine. [The identification and remediation of clinical reasoning difficulties in medicine]. (État des pratiques, recherche d’outils et processus pour soutenir les cliniciens enseignants)MontrealUniversité de Montréal2010 French

- BearmanMMolloyEAjjawiRKeatingJ“Is there a plan B?”: clinical educators supporting underperforming students in practice settingsTeach High Educ2013185531544

- ReesCEKnightLVClelandJAMedical educators’ metaphoric talk about their assessment relationships with students: “You don’t want to sort of be the one who sticks the knife in them”Assess Eval High Educ2009344455467

- MonrouxeLVReesCELewisNJClelandJAMedical educators’ social acts of explaining passing underperformance in students: a qualitative studyAdv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract201116223925221063770

- ClelandKnight LVReesCETraceySBondCMIs it me or is it them? Factors that influence the passing of underperforming studentsMed Educ200842880080918715477

- LacasseMDiagnostic et prise en charge des situations d’apprentissage problématiques en éducation médicale. [Educational diagnosis and management of challenging learning situations in medical education]QuebecUniversité Laval2009 French

- YaoDCWrightSMNational survey of internal medicine residency program directors regarding problem residentsJAMA200028491099110410974688

- NascaTJPhilibertIBrighamTFlynnTCThe next GME accreditation system: rationale and benefitsN Engl J Med2012366111051105622356262

- ten CateOEntrustability of professional activities and competency-based trainingMed Educ200539121176117716313574

- PaiceEIdentification and management of the underperforming surgical traineeANZ J Surg200979318018519317785

- SteinertYNasmithLDaigleNFrancoEDImproving teachers’ skills in working with “problem” residents: a workshop description and evaluationMed Teach200123328428812098400

- ArawiTRosoffPMCompeting duties: medical educators, underperforming students, and social accountabilityJ Bioeth Inq20129213514723180257

- BernsteinSAtkinsonARMartimianakisMADiagnosing the learner in difficultyPediatrics2013132221021223858429

- RegehrGEvaKSelf-assessment, self-direction, and the self-regulating professionalClin Orthop Relat Res2006449343816735869

- KrugerJDunningDUnskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessmentsJ Pers Soc Psychol19997761121113410626367

- TorreDMTreatRDurningSElnickiDMComparing PDA- and paper-based evaluation of the clinical skills of third-year studentsWMJ2011110191321473507

- PulitoARDonnellyMBPlymaleMMentzerRMJrWhat do faculty observe of medical students’ clinical performance?Teach Learn Med20061829910416626266

- LacasseMThéorêtJSkalendaPLeeSChallenging learning situations in medical education: innovative and structured tools for assessment, educational diagnosis, and intervention. Part 2: objective examination, assessment, and planCan Fam Physician2012587802803e418e82022798468

- NendazMCharlinBLeblancVBordageGLe raisonnement clinique: données issues de la recherche et implications pour l’enseignement. [Clinical reasoning: from research findings to applications for teaching]Pedagog Med200564235254 French

- EpsteinRMAssessment in medical educationN Engl J Med2007356438739617251535

- JouquanJL’évaluation des apprentissages des étudiants en formation médicale initiale. [The assessment of medical students’ learning]Pedagog Med2002313852 French

- HinsonJPGriffinARavenPWHow to support medical students in difficulty: tips for GP tutorsEduc Prim Care2011221323521333129

- PaulGHinmanGDottlSPassonJAcademic development: a survey of academic difficulties experienced by medical students and support services providedTeach Learn Med200921325426020183347

- YatesJ“Concerns” about medical students’ adverse behaviour and attitude: an audit of practice at Nottingham, with mapping to GMC guidanceBMC Med Educ20141419625239087

- MitchellMSrinivasanMWestDCFactors affecting resident performance: development of a theoretical model and a focused literature reviewAcad Med200580437638915793024

- HendrenRLPredicting success and failure of medical students at risk for dismissalJ Med Educ19886385966023398014

- BouléRGirardGBernierCDépistage précoce des résidents en difficulté. [Early detection of residents in trouble]Can Fam Physician19954121302135 French8680296

- ToneskXBuchananRGAn AAMC pilot study by 10 medical schools of clinical evaluation of studentsJ Med Educ19876297077183625734

- KahnNBDealing with the problem learnerFam Med200133965565711665900

- ReamyBVHarmanJHResidents in trouble: an in-depth assessment of the 25-year experience of a single family medicine residencyFam Med200638425225716586171

- KempainenRRMigeonMBWolfFMUnderstanding our mistakes: a primer on errors in clinical reasoningMed Teach200325217718112745527

- ScottIAErrors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategiesBMJ2009338b186019505957

- LuhangaFLLarocqueSMacEwanLGwekwerereYNDanylukPExploring the issue of failure to fail in professional education programs: a multidisciplinary studyJ Univ Teach Learn Pract2014112124

- WinstonKAVan Der VleutenCPScherpbierAJThe role of the teacher in remediating at-risk medical studentsMed Teach20123411e732e74222658068

- AudetatMCLaurinSDoryVRemediation for struggling learners: putting an end to ‘more of the same’Med Educ201347323023123398008

- ClelandLeggett HSandarsJCostaMJPatelRMoffatMThe remediation challenge: theoretical and methodological insights from a systematic reviewMed Educ201347324225123398010

- SaxenaVO’SullivanPSTeheraniAIrbyDMHauerKERemediation techniques for student performance problems after a comprehensive clinical skills assessmentAcad Med200984566967619704207

- HauerKETeheraniAKerrKMO’SullivanPSIrbyDMStudent performance problems in medical school clinical skills assessmentsAcad Med20078210 SupplS69S7217895695

- RegehrGNormanGRIssues in cognitive psychology: implications for professional educationAcad Med199671998810019125988

- NendazMPerrierADiagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning: mechanisms and prevention in practiceSwiss Med Wkly2012142w1370623135902

- TardifJPour un enseignement stratégique : l’apport de la psychologie cognitive. [Strategic education: contributions from cognitive psychology]MontrealEditions Logiques1992 French

- SetnaZJhaVBoursicotKARobertsTEEvaluating the utility of workplace-based assessment tools for speciality trainingBest Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol201024676778220598644

- AudétatMCLaurinSSancheGBéïqueCCaire FonNBlaisJGCharlinBClinical reasoning difficulties: a taxonomy for clinical teachersMed teach2013353e984e98923228082