Abstract

Breast cancer in young women is relatively rare compared to breast cancer occurring in older women. Younger women diagnosed with breast cancer also tend to have a more aggressive biology and consequently a poorer prognosis than older women. In addition, they face unique challenges such as diminished fertility from premature ovarian failure, extended survivorship periods and its attendant problems, and the psychosocial impact of diagnosis, while still raising families. It is therefore imperative to recognize the unique issues that younger women face, and plan management in a multidisciplinary fashion to optimize clinical outcomes. This paper discusses the challenges of breast cancer management for young women, as well as specific issues to consider in diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of such patients.

Introduction

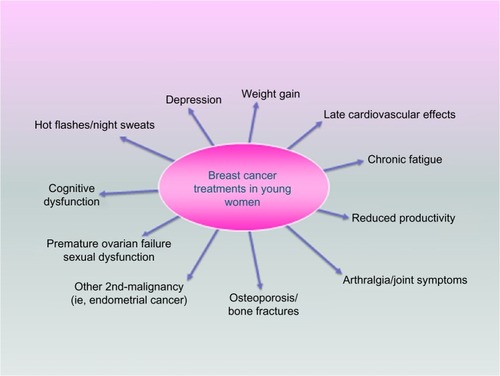

Early-onset breast cancer is relatively rare; however, it represents the commonest cause of cancer in women under age the of 40.Citation1 In the US, approximately 33,000 women under the age of 45 years are diagnosed with breast cancer every year, and it is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in this age group.Citation2 Compared to older women with breast cancer, younger women tend to have a more aggressive biology and a poorer prognosis (). Younger women with breast cancer also face unique challenges such as premature ovarian failure, psychosocial issues with ongoing careers, and raising young families, as well as extended survivorship periods and its attendant complications as summarized in . It is therefore imperative to recognize the unique issues that younger women face and plan management in a multidisciplinary fashion to optimize clinical outcomes.

Table 1 Breast cancer features in younger patients

Breast cancer screening

Screening for breast cancer should begin at age 40 for average-risk women.Citation3 This includes annual mammography and clinical breast examination (CBE). Breast self-examination (BSE) is an additional option. For average-risk women under age 40, screening consists of CBE every 3 years with optional BSE; routine use of imaging is not recommended. Although no studies have documented improved breast cancer-related outcomes with BSE, given that routine imaging is not warranted, most malignancies in women under 40 will be detected by patients.Citation4 Even for young women who do undergo annual mammography, cancers that develop are more likely to present as interval cancers.Citation5–Citation7 For this reason as well, CBE and BSE remain important screening modalities for young women. Increased breast density seen in younger women lowers the sensitivity of mammography.Citation8 Despite this, mammography is still an important screening tool. The incorporation of tomosynthesis, or three-dimensional mammography, will likely improve the sensitivity and specificity of mammography in women with dense breast tissue.Citation9

Diagnostic evaluation of young women with breast complaints

Women, regardless of age, who present with symptoms, require diagnostic evaluation and a CBE. Because younger women do not undergo routine screening mammography, most will present with symptomatic and higher stage breast cancerCitation10,Citation11 versus women diagnosed with a screening study. Young age and symptomatic presentation are both associated with delay in diagnosis and worse outcomes.Citation10–Citation12 The imaging modality selected for the diagnostic workup depends on the patient’s age and presenting symptoms.Citation13–Citation16 Masses should be evaluated by ultrasound with or without mammography, depending on the patient’s age, the clinical suspicion, and the nature of the mass. Pathologic nipple discharge concerning for ductal carcinoma in situ may mandate mammography even in younger women to evaluate for calcifications. Magnetic resonance (MR) is typically not indicated for evaluation of mammographic or ultrasound abnormalities; suspicious findings on conventional imaging or examination require standard evaluation, including biopsy, even in the setting of a negative MR. Negative imaging of any type does not negate the possibility of malignancy, and therefore even in the setting of normal imaging, suspicious palpable findings require biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

Genetic predisposition

First-degree relatives of women with breast cancer have nearly a twofold increased breast cancer risk compared to the general population, and this risk is much higher when the relative is diagnosed at a young age.Citation17,Citation18 Large twin studies have demonstrated nearly one-third of all breast cancer is attributed to hereditary factors.Citation19,Citation20 However, the susceptibility genes identified to date account for only 20%–30% of the excess familial risk.Citation21,Citation22 Consequently, the genetic etiology for the majority of families with an increased familial breast cancer risk remains unknown.

Young age at diagnosis is a feature of hereditary disease, and it is currently recommended that all women diagnosed with breast cancer less than 40 years of age be referred for genetics assessment. A higher proportion of young women with breast cancer have germline mutations, compared to their older counterparts, with most studies evaluating the prevalence of BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 mutations.Citation23–Citation25 Furthermore, a greater proportion of young women, especially black women, have triple-negative disease, and among these women there is also an increased frequency of germline mutations, notably in BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 genes.Citation26 Identification of germline mutations has the potential to impact a woman’s medical care, and to be informative for at-risk family members.

Multiple gene panels, with concurrent analysis of genes with varied levels of breast cancer risk, are now commonly used in clinical practice. Maxwell et alCitation27 evaluated the use of a 22-gene panel among a cohort of young women with breast cancer, classifying the results into clinically actionable and unclear actionability, based on the available data of the risks associated with each gene. Only 2.5% of this cohort of 278 patients was identified with clinically actionable gene variants compared to 8.6% of patients with variants for which clinical data are deficient.Citation27 The current lack of clinical validity for many genes makes translating clinical genetic testing results into improved patient care difficult, with the potential for overtreatment. Some investigators have advocated that genetic testing for breast cancer risk should only be offered after the clinical validity is established for the genes to be analyzed.Citation28 Until additional cancer susceptibility genes are discovered and clinical validation of recently discovered genes is performed, clinicians will need to continue to rely on the family cancer history to help guide medical care for the majority of young women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Biology of early-onset breast cancer

Differences in pathologic characteristics between younger and older women with breast cancers have been observed in multiple studies. The Prospective study of Outcomes in Sporadic and Hereditary breast cancer is the largest to investigate factors affecting breast cancer prognosis in patients ≤40 years; however, there is no comparison to older women due to the observational nature of the study.Citation29 Although only 30% of the patients had screen-detected cancers, 50% of the patients in this multicenter study presented with nodal involvement. One-third of them were hormone receptor (HR) negative, 20% had triple-negative breast cancer, and almost 60% had poorly differentiated tumors. In addition, although majority of patients received chemotherapy in addition to endocrine therapy, 10% of those with HR-positive breast cancer developed a late relapse between years 5 and 8. At a median follow-up of 5 years, the overall survival was 82%, with the majority of deaths due to breast cancer. Another large study using the California Cancer Registry also found that 20% of adolescents and young adults with breast cancer had triple-negative disease and 54% had high-grade tumors.Citation30 Numerous other studies have also suggested more biologically aggressive cancers in younger women.Citation10,Citation31–Citation37

Gene expression profiling has subdivided triple-negative-breast cancer (TNBC) patients into clinically relevant subtypes now being used to design clinical trials.Citation38 A comprehensive study on TNBC samples revealed several biomarkers, including TP53, PIK3CA, AKT1, PTEN, and HER2 mutations that may be therapeutically relevant in the future.Citation39 Clinical trials investigating agents targeted at such aberrations are underway. For example, a recent open-label Phase II trial investigating enzalutamide, an androgen receptor (AR) antagonist, in AR-positive advanced TNBC patients, reported a 16-week clinical benefit rate of 35%.Citation40 TNBC cases that were strongly AR-positive exhibited lower proliferation rates than those that were not AR-positive.Citation39 These AR-positive tumors tend to be rich in genes regulated by the hormonal pathway.

TNBC is an immunogenic form of breast cancer due to the frequency of mutations causing neoantigens, and the association between high rates of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and improved response to chemotherapy and survival seen in that subset of breast cancer.Citation41,Citation42 Novel immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as the PDL1 and PD1 inhibitors, appear to have activity in TNBC patients as well. Two studies utilizing these agents in the advanced TNBC setting reported durable clinical benefits in patients with PDL1-positive TNBC.Citation43,Citation44 Thus, new predictive markers in TNBC may prove to be therapeutically relevant in the future.

Several groups have also found gene expression profile differences between breast cancers occurring in younger versus older women. In the largest study evaluating age-related biological differences in breast cancer, Azim et alCitation45 found that genes enriched in processes related to immature mammary cell populations (RANKL, c-kit, BRCA1, mammary stem cells, and luminal progenitors cells) and growth factor signaling (MAPK, PI3K) were predominant in younger women.

Analysis of clinically annotated microarray data from 784 breast cancer patients also revealed that young women ≤45 years had lower mRNA expression of ERα, ERβ, and PR, but higher expression of HER2 and EGFR as opposed to women ≤65 years.Citation46 In women <40 years, gene expression profiling further showed lower expression of ERα and ERβ compared with women 40–50 years. In addition, gene sets unique to younger women included those related to biologically relevant and potentially actionable processes such as immune function, mTOR/rapamycin pathway, hypoxia, BRCA1, stem cells, apoptosis, histone deacetylase, and multiple oncogenic signaling pathways.

Differences in biology in young women also differ by race. In a large Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) study involving over 126,000 women aged ≤49 years with breast cancer, we have previously reported that a higher proportion of blacks versus whites developed breast cancer under age 40. A higher proportion of blacks also presented with HR negative, more advanced stage, and higher grade tumors.Citation47 In the Carolina Breast Cancer Study, the prevalence of basal-like breast cancer was highest (39%) among black premenopausal women compared with other groups of patients (14%–16%).Citation48 This has also been observed in other studies in the US.Citation49,Citation50

Prognosis

A recent study showed an increase in the incidence of young women aged 25–39 years diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer from 1.53 to 2.90 per 100,000 from 1976 to 2009.Citation51 Several reasons such as stage migration, improved surveillance, and population-based changes in breast cancer risk factors may be implicated. This increase is particularly concerning as young age is an independent adverse factor for poor prognosis among women with breast cancer.Citation1,Citation52–Citation56 The clinical outcome is worsened for very young women under age 35, with the hazard of death increasing by every 1 year decrease in age.Citation57 It is also apparent that the effect of age on outcome is modified by breast cancer subtype. A study by Sheridan et alCitation58 showed that within the HR-positive subtype, younger age carried a worse prognosis than older age. This has also been confirmed in Azim et al’sCitation45 study, where they found an inferior relapse-free survival with young age in the HR-positive/HER2-negative subtype in a subgroup analysis.

Treatment

Locoregional treatment – surgery

Young women with breast cancer have similar surgical options as older women. These include breast conservation therapy (BCT) (partial mastectomy with radiation) or mastectomy. Although young age at diagnosis is associated with a higher risk of local recurrence and more aggressive phenotypes, data suggest no survival gains with mastectomy compared to BCT, and there does not appear to be a survival advantage with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy either.Citation59–Citation63 Therefore, young age alone is not a contraindication to BCT. Despite this, bilateral mastectomies are on the rise in women of all ages.Citation61–Citation63 This is likely due to patient and physician perception of improved outcomes and due to improved reconstruction techniques and cosmesis. Immediate and immediate-delayed reconstruction are now preferred, and many women are candidates for nipple sparing procedures with immediate or immediate-delayed reconstruction. Nipple sparing procedures are increasingly being offered as data supports the oncologic safety, and these procedures are associated with better self-image.Citation64,Citation65

Locoregional treatment – radiotherapy

After partial mastectomy, adjuvant whole breast radiation has been shown to reduce the risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence, as well as improve breast cancer survival.Citation66,Citation67 Adjuvant radiation is especially important for young women in this setting, as their absolute risk of local recurrence is higher than for older women, and as a result, younger women have a greater absolute benefit from adjuvant radiation.Citation67

For young women with early-stage breast cancer, there are important considerations with regards to treatment volume. Accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) may not be an appropriate option for young women. Although results from the NSABP B-39 trial,Citation68 comparing whole and partial breast radiation, are pending, there are several published consensus statements describing APBI selection criteria. All include a minimum patient age in their criteria, ranging from 45 to 60 years as the suggested minimum age.Citation69–Citation71 This is based on the existing published literature on APBI which primarily includes women over 50, the concern for increased risk of multifocal and multicentric disease in younger women, and the known higher local recurrence rates seen in young women who receive whole breast radiation. NSABP B-39 trial included women over 18 years old, and we await the results from this trial.

Other considerations with regards to dose and fractionation include the use of boost and hypofractionation. In the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer trial, use of boost reduced the 20-year cumulative incidence of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence from 16.4% to 12.0% (hazard ratio: 0.65, P<0.0001).Citation72 The benefit of a boost was found to be greatest for young women. The absolute risk reduction was 4.4% in the entire cohort, and 11.6% for women under 40. Hypofractionated whole-breast schedules have been found to be as effective as standard fractionation for certain populations. However, majority of these data were obtained in women over 50 years old, and therefore the American Society for Radiation Oncology guidelines on fractionation support the use of hypofractionation only for women over 50, who also meet the other specified criteria.Citation73 Until further evidence is available for younger women, the standard of care for these women includes delivery of whole-breast radiation with standard fractionation.

For women with locally advanced breast cancer, randomized trials have demonstrated a locoregional recurrence and survival benefit to postmastectomy radiation for women with large primary tumors >5 cm, invasion of the skin or chest wall, or lymph node involvement.Citation74–Citation76 Retrospective analysis of 107 stage II or III patients aged ≤35 years treated with or without adjuvant radiation following mastectomy showed that patients who received postmastectomy radiation compared with those who did not had a better 5-year local control and overall survival rates.Citation77 Since young age and/or premenopausal status are risk factors for locoregional recurrence after mastectomy, some young women with node negative disease may benefit from postmastectomy radiation if they have additional risk factors.Citation78–Citation80

For most breast cancer scenarios, young women have a higher risk of local and regional recurrence, and therefore derive an even greater absolute benefit from adjuvant radiation than older women. Given their young age and potential for long-term survival, special care must be taken during radiation treatment planning to minimize radiation exposure to adjacent organs in order to reduce the risk of late effects and secondary malignancies.

Systemic treatment – endocrine

The Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group’s (EBCTCG) meta-analyses demonstrated that 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen improved the annual breast cancer death rate by one-third and recurrence risk by 50% for all women with HR-positive cancers irrespective of age.Citation81 However, approximately 10% of those with HR-positive cancers will develop a late relapse beyond year 5; therefore, there has been interest in extending adjuvant endocrine therapy to prevent later relapses. In the Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Longer Against Shorter trial, women with early stage breast cancer were randomly assigned to continue tamoxifen to 10 years or stop at 5.Citation82 Allocation to 10 years was associated with reductions in the risk of recurrence, improvements in breast cancer specific survival, and overall survival. Similarly, in the UK adjuvant Tamoxifen-To offer more? trial, 10 years of adjuvant tamoxifen reduced late breast cancer recurrences and mortality among women with HR-positive cancers.Citation83 The group that continued tamoxifen to year 10 had further reductions in recurrence, from year 7 onward, as well as breast cancer mortality after year 10. Based on these and other studies, the American Society for Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline now recommends treatment with adjuvant tamoxifen for 10 years in women with stage I–III HR-positive cancers. While these results were not restricted to young women, in clinical practice, young patients who are believed to have a worse prognosis are generally being considered for 10 rather than 5 years of tamoxifen.

An alternative form of endocrine manipulation involves ovarian suppression (OS). Although, the prognosis for pre-menopausal women who have chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea (CIA) is better than for those who do not have CIA, the prognostic value of therapeutic OS remains unclear.Citation84–Citation86 The Suppression of Ovarian Function (SOFT) trial was designed to determine the utility of dual endocrine blockade by adding OS to tamoxifen and also to determine the benefit of an aromatase inhibitor with OS for premenopausal patients.Citation87 Premenopausal women were assigned to either 5 years of tamoxifen, tamoxifen plus OS, or exemestane plus OS. At 5 years, 90.9% of those who received exemestane with OS were free from breast cancer, versus 88.4% in the tamoxifen plus OS arm, versus 86.4% in the tamoxifen alone group. In the subgroup of women younger than 35 years, the rate of freedom from breast cancer at 5 years was 83.4% for those assigned to exemestane plus OS, 78.9% for those assigned to tamoxifen plus OS, and 67.7% for patients assigned to tamoxifen alone. Similarly, the Tamoxifen and Exemestane Trial (TEXT) was designed to compare exemestane plus OS versus tamoxifen plus OS also in premenopausal women.Citation88 In the combined analysis of both SOFT and TEXT trials, the 5-year rate of freedom from breast cancer was 92.8% in those receiving exemestane plus OS, versus 88.8% for those assigned to receive tamoxifen plus OS. The symptom burden of OS with either tamoxifen or exemestane is higher than tamoxifen alone and different depending on what drug is given in combination with OS. Patients who receive tamoxifen have more vasomotor symptoms, while those who receive exemestane have more arthralgia, sexual dysfunction, and vaginal dryness.Citation89 These side effects need to be discussed with individual patients prior to electing treatment. Results from these studies show that even in premenopausal women with early stage breast cancer, the outcomes in those with HR-positive cancers is very good in general; however, there is still a need to define who merits more aggressive therapy. In addition, further tools and research are needed on compliance, management of menopausal symptoms, bone loss, cognitive problems, and sexual dysfunction, and careful monitoring of late side effects such as secondary malignancies.

Systemic treatment – chemotherapy

The preferred chemotherapy regimens remain the same for all patients with early stage breast cancer irrespective of age. In general, for most high-risk breast cancer patients, combination regimens including anthracyclines and taxanes are employed. The EBCTCG meta-analyses, evaluated the benefits of adjuvant polychemotherapy on outcomes in younger versus older women.Citation81 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy combinations had a larger impact in reducing the annual breast cancer death rate for women younger than 50 years (38% reduction) versus 20% for those aged 50–69 years. In addition, there was also a threefold age-related benefit for polychemotherapy versus no chemotherapy for women <50 years versus women 50–69 years with larger benefits for recurrences than mortality. The 5-year improvements from chemotherapy were approximately twofold for HR-negative versus HR-positive cancers, but the 15-year improvements were less dependent on HR status, likely due to differences in timing of recurrences with HR-negative versus HR-positive cancers. Preferred National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for adjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk HR-breast cancer patients include several regimens such as doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel or docetaxel plus cyclophosphamide.

Systemic treatment – biologic therapy

Patients who have HER2+ breast cancer receive trastuzumab as part of their (neo)adjuvant systemic treatment based on improvements in overall survival seen in large randomized trials.Citation90–Citation93 Young patients also derive similar benefits from adjuvant trastuzumab as older patients.Citation12 Pertuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed at HER2 and is approved in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy for treatment of HER2+ breast cancers in the neoadjuvant and advanced settings based on several studies.Citation94–Citation96

Unique considerations

Fertility preservation

Among the unique concerns for young women with breast cancer are treatment-induced ovarian failure and infertility. The risk of infertility varies according to age, reproductive reserve, chemotherapy agent, duration of treatment, and dose administered.Citation97 Alkylating agents are among those with the highest gonadotoxic properties.Citation98 The true rates of infertility after breast cancer treatments have been difficult to ascertain as there is no consensus on what constitutes infertility. Different surrogates used in different studies include amenorrhea, estradiol, anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin B, and follicle count.Citation99,Citation100

Young women who are desirous of future childbearing should be properly counseled by an oncofertility specialist on options for fertility preservation prior to chemotherapy. Existing reproductive options include embryo and oocyte cryopreservation, cryopreservation of ovarian tissue, or OS with luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists.Citation101–Citation103 The POEMS study randomized 257 pre-menopausal women with HR-negative breast cancer to receive standard chemotherapy with or without goserelin to determine if goserelin reduced ovarian failure.Citation104 The ovarian failure rate was 8% in the intervention group versus 22% in the chemotherapy group. In addition, 22 patients in the goserelin group achieved at least 1 pregnancy versus 12 in the standard group, although more women in the goserelin group attempted pregnancy. While these data are encouraging, the use in those with HR-positive cancer is cautioned, as this study only included those with HR-negative cancer. Although less of an issue with LHRH agonists that are administered during chemotherapy, practical barriers limiting fertility preservation are cost, insurance, absence of a male partner, and chemotherapy timing issues.

Retrospective studies have suggested no worsening of breast cancer outcomes in patients who become pregnant.Citation105–Citation108 POSITIVE (Pregnancy Outcome and Safety of Interrupting Therapy for women with endocrine responsIVE Breast Cancer) is an ongoing trial, designed to evaluate the safety and outcomes of women with HR-positive cancers who interrupt endocrine therapy for childbearing. This trial seeks to enroll women under age 42 who have received 18–30 months of endocrine therapy and who then stop endocrine therapy temporarily to attempt pregnancy.Citation109 Guidelines also recommend avoiding pregnancy within 6 months of systemic therapy completion, due to teratogenicity.Citation110,Citation111

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer

The incidence of pregnancy at the time of breast cancer diagnosis is approximately 1.5%, and breast cancer is the most common pregnancy-associated malignancy in women.Citation112–Citation114 A confirmed diagnosis of malignancy should prompt diagnostic mammography in addition to ultrasound with uterine shielding.Citation115 Fine needle aspiration may be difficult to interpret in the setting of pregnancy-related proliferative changes;Citation116 core biopsy is preferred. The pathologist should be alerted to the patient’s gravid state. Staging should be directed by signs and symptoms and by clinical stage as for the nonpregnant patient. Computed tomography, plain X-ray, and nuclear medicine studies expose the fetus to radiation, and so risks and benefits of this exposure need to be weighed. Nuclear medicine studies are typically avoided due to a lack of safety data, and breast MR, which requires gadolinium contrast, is not safe during pregnancy.Citation117,Citation118

Surgery is often the safest mode of treatment during early pregnancy as endocrine and cytotoxic therapies are contraindicated during the first trimester.Citation119 For patients who undergo surgery early in pregnancy and who do not need adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation may be delayed many months although studies suggest worse outcomes with such delays.Citation120 Fetal radiation exposure is associated with birth defects, mental retardation, childhood malignancy, and other complications, and as the fetus grows its proximity to the breast increases, the potential for fetal radiation exposure increases.Citation119,Citation121 Therefore, radiation is contraindicated in the third trimester. Clinically node-negative women undergo axillary staging with a sentinel lymph node biopsy. Traditionally, radioisotope was avoided due to the risk of radiation exposure to the fetus. More recent data suggest that the dose to the fetus is small, and available data suggest no negative impact on pregnancy outcomes with the use of radioisotope.Citation122,Citation123 This method of sentinel node mapping may be preferred due to continued concerns about teratogenicity or maternal anaphylaxis with methylene blue and isosulfan blue dye, respectively, both of which are Pregnancy Class C drugs. A small series, however, has not demonstrated negative pregnancy outcomes with the use of blue dyes.Citation123 The potential risks and benefits of the sentinel node procedure need to be discussed with patients preoperatively.

Fetal malformations are seen with first trimester exposure to chemotherapy.Citation124 Anthracycline-based regimens have the most available data and can be given during the second and third trimesters.Citation125–Citation127 Chemotherapy should be withheld ideally at least 3 weeks before confinement to avoid cytopenias at the time of delivery. Other systemic therapies such as endocrine therapy and trastuzumab are contraindicated during pregnancy.Citation128

Bone health

Young women with breast cancer are at higher risk of long-term side effects from cancer treatments and survivorship due to the longer life expectancy. One particular area which has received a lot of recent attention is bone health. Although fragility fractures are more common in women over 50 years, several factors lead to bone compromise in younger women treated for breast cancer. Androgens and estrogens are regulators of bone growth, and consequently, estrogen deficiency is a key determinant in bone loss. Cancer treatments with chemotherapy can lead to estrogen deficiency via gonadal dysfunction, and also impair bone health via direct effects on bone metabolism or systemic steroids commonly used as supportive medications during chemotherapy. Radiation can impair bone integrity in the treated radiation field. Hormonal treatment designed to induce hypogonadism also leads to accelerated bone loss. In premenopausal women receiving endocrine therapy for breast cancer, changes in bone mineral density have been observed with tamoxifen, ovarian suppression, tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors with ovarian suppression, and oophorectomy.Citation129–Citation131 Thresholds for pharmacologic intervention with bisphosphonates or RANK ligand inhibitors include a history of osteoporosis, fragility fractures, and osteopenia with additional risk factors. Several studies have confirmed that antiresorptive therapies maintain or increase bone mineral density in women or men treated with endocrine therapy.Citation129,Citation132–Citation137 While this is encouraging, it remains unclear what impact these treatments have on the incidence of fractures in those at risk.

Conclusion

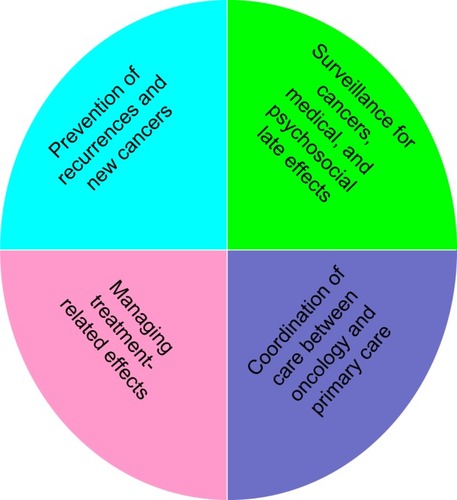

Young patients with breast cancer face unique management challenges that are best addressed in a multidisciplinary setting. Currently, treatment recommendations are made on tumor characteristics and not solely on age. Close attention to long-term side effects with optimal supportive care should be considered. A survivorship care plan involving a multidisciplinary team is essential for young patients (). Younger patients are also underrepresented in clinical trials and should be encouraged to participate for a better understanding of early-onset breast cancer.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 1K12CA167540 through the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes for Health (NIH) and Grant Number UL1 TR000448 through the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Cancer for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the NIH. Its contents, however, are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCI, NCATS, or NIH.

References

- BleyerABarrRHayes-LattinBThe distinctive biology of cancer in adolescents and young adultsNat Rev Cancer20088428829818354417

- HowladerNNooneAMKrapchoMSEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012Bethesda, MDNational Cancer Institute2014 Based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2015. Available from: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/Accessed November 12, 2015

- SmithRASaslowDSawyerKAAmerican Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003CA Cancer J Clin200353314116912809408

- FancherTTPalestyJAPaszkowiakJJKiranRPMalkanADDudrickSJCan breast self-examination continue to be touted justifiably as an optional practice?Int J Surg Oncol2011201196546422312535

- WilkeLGBroadwaterGRabinerSBreast self-examination: defining a cohort still in needAm J Surg2009198457557919800471

- AnYYKimSHKangBJParkCSJungNYKimJYBreast cancer in very young women (<30 years): correlation of imaging features with clinicopathological features and immunohistochemical subtypesEur J Radiol201584101894190226198117

- GoksuSSTastekinDArslanDClinicopathologic features and molecular subtypes of breast cancer in young women (age ≤35)Asian Pac J Cancer Prev201415166665666825169505

- CheckaCMChunJESchnabelFRLeeJTothHThe relationship of mammographic density and age: implications for breast cancer screeningAJR Am J Roentgenol20121983W292W29522358028

- GilbertFJTuckerLGillanMGThe TOMMY trial: a comparison of TOMosynthesis with digital MammographY in the UK NHS Breast Screening Programme – a multicentre retrospective reading study comparing the diagnostic performance of digital breast tomosynthesis and digital mammography with digital mammography aloneHealth Technol Assess2015194ixxv113625599513

- ZabickiKColbertJADominguezFJBreast cancer diagnosis in women ≤40 versus 50 to 60 years: increasing size and stage disparity compared with older women over timeAnn Surg Oncol20061381072107716865599

- PartridgeAHHughesMEOttesenRAThe effect of age on delay in diagnosis and stage of breast cancerOncologist201217677578222554997

- PartridgeAHGelberSPiccart-GebhartMJEffect of age on breast cancer outcomes in women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: results from a herceptin adjuvant trialJ Clin Oncol201331212692269823752109

- NewellMSD’OrsiCMahoneyMCAmerican College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Nonpalpable Mammographic Findings (Excluding Calcifications) [cited August 17, 2015] Available from: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/NonpalpableMammographicFindings.pdfAccessed November 12, 2015

- HarveyJAMahoneyMCNewellMSAmerican College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Palpable Breast Masses [cited August 17, 2015] Available from: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/PalpableBreastMasses.pdfAccessed November 12, 2015

- ComstockCHD’OrsiCBassettLWAmerican College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Breast Microcalcifications – Initial Diagnostic Workup [cited August 17, 2015] Available from: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/BreastMicrocalcifications.pdfAccessed November 12, 2015

- DershawDDD’OrsiCMahoneyMCACR Practice Parameter for the Imaging Management of DCIS and Invasive Breast Carcinoma [cited August 17, 2015] Available from: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/PGTS/guidelines/DCIS_Invasive_Breast_Carcinoma.pdfAccessed November 12, 2015

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast CancerFamilial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the diseaseLancet200135892911389139911705483

- DiteGSJenkinsMASoutheyMCFamilial risks, early-onset breast cancer, and BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutationsJ Natl Cancer Inst200395644845712644538

- LichtensteinPHolmNVVerkasaloPKEnvironmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer – analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and FinlandN Engl J Med20003432788510891514

- PetoJMackTMHigh constant incidence in twins and other relatives of women with breast cancerNat Genet200026441141411101836

- MichailidouKHolmNVVerkasaloPKGenome-wide association analysis of more than 120,000 individuals identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for breast cancerNat Genet201547437338025751625

- MichailidouKHallPGonzalez-NeiraALarge-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer riskNat Genet2013454353361361.e1e223535729

- LallooFVarleyJMoranABRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 mutations in very early-onset breast cancer with associated risks to relativesEur J Cancer20064281143115016644204

- HafftyBGChoiDHGoyalSBreast cancer in young women (YBC): prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations and risk of secondary malignancies across diverse racial groupsAnn Oncol200920101653165919491284

- PetoJCollinsNBarfootRPrevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with early-onset breast cancerJ Natl Cancer Inst1999911194394910359546

- CouchFJHartSNSharmaPInherited mutations in 17 breast cancer susceptibility genes among a large triple-negative breast cancer cohort unselected for family history of breast cancerJ Clin Oncol201533430431125452441

- MaxwellKNWubbenhorstBD’AndreaKPrevalence of mutations in a panel of breast cancer susceptibility genes in BRCA1/2-negative patients with early-onset breast cancerGenet Med201517863063825503501

- EastonDFPharoahPDAntoniouACGene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer riskN Engl J Med2015372232243225726014596

- CopsonEEcclesBMaishmanTProspective observational study of breast cancer treatment outcomes for UK women aged 18–40 years at diagnosis: the POSH studyJ Natl Cancer Inst20131051397898823723422

- KeeganTHDeRouenMCPressDJKurianAWClarkeCAOccurrence of breast cancer subtypes in adolescent and young adult womenBreast Cancer Res2012142R5522452927

- AhnSHSonBHKimSWPoor outcome of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer at very young age is due to tamoxifen resistance: nationwide survival data in Korea – a report from the Korean Breast Cancer SocietyJ Clin Oncol200725172360236817515570

- WalkerRALeesEWebbMBDearingSJBreast carcinomas occurring in young women (<35 years) are differentBr J Cancer19967411179618008956795

- Gonzalez-AnguloAMBroglioKKauSWWomen age ≤35 years with primary breast carcinoma: disease features at presentationCancer2005103122466247215852360

- XiongQValeroVKauVFemale patients with breast carcinoma age 30 years and younger have a poor prognosis: the MD Anderson Cancer Center experienceCancer200192102523252811745185

- SidoniACavaliereABellezzaGScheibelMBucciarelliEBreast cancer in young women: clinicopathological features and biological specificityBreast200312424725014659308

- CollinsLCMarottiJDGelberSPathologic features and molecular phenotype by patient age in a large cohort of young women with breast cancerBreast Cancer Res Treat201213131061106622080245

- GnerlichJLDeshpandeADJeffeDBSweetAWhiteNMargenthalerJAElevated breast cancer mortality in women younger than age 40 years compared with older women is attributed to poorer survival in early-stage diseaseJ Am Coll Surg2009208334134719317994

- LehmannBDBauerJAChenXIdentification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapiesJ Clin Invest201112172750276721633166

- MillisSZGatalicaZWinklerJPredictive biomarker profiling of >6000 breast cancer patients shows heterogeneity in TNBC, with treatment implicationsClin Breast Cancer Epub2015428

- TrainaTAMillerKYardleyDAResults from a phase 2 study of enzalutamide (ENZA), an androgen receptor (AR) inhibitor, in advanced AR+ triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)Paper presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual MeetingMay 29, 2015Chicago, IL

- LoiSSirtaineNPietteFPrognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02-98J Clin Oncol201331786086723341518

- DenkertCvon MinckwitzGBraseJCTumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without carboplatin in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive and triple-negative primary breast cancersJ Clin Oncol201533998399125534375

- NandaRPlimackERDeesECA phase Ib multicohort study of MK-3475 in patients with advanced solid tumorsPaper presented at: American Society of Clinical OncologyMay 30, 2014Chicago, IL

- EmensLABraitehFSCassierPInhibition of PD-L1 by MPDL3280A leads to clinical activity in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)Paper presented at: American Association for Cancer ResearchApril 18–22, 2015Pennsylvania, PA

- AzimHAJrMichielsSBedardPLElucidating prognosis and biology of breast cancer arising in young women using gene expression profilingClin Cancer Res20121851341135122261811

- AndersCKHsuDSBroadwaterGYoung age at diagnosis correlates with worse prognosis and defines a subset of breast cancers with shared patterns of gene expressionJ Clin Oncol200826203324333018612148

- AdemuyiwaFOGaoFHaoLUS breast cancer mortality trends in young women according to raceCancer201512191469147625483625

- CareyLAPerouCMLivasyCARace, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer StudyJAMA2006295212492250216757721

- BauerKRBrownMCressRDPariseCACaggianoVDescriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California cancer RegistryCancer200710991721172817387718

- LundMJTriversKFPorterPLRace and triple negative threats to breast cancer survival: a population-based study in Atlanta, GABreast Cancer Res Treat2009113235737018324472

- JohnsonRHChienFLBleyerAIncidence of breast cancer with distant involvement among women in the United States, 1976 to 2009JAMA2013309880080523443443

- AndersCKJohnsonRLittonJPhillipsMBleyerABreast cancer before age 40 yearsSemin Oncol200936323724919460581

- FredholmHEakerSFrisellJHolmbergLFredrikssonILindmanHBreast cancer in young women: poor survival despite intensive treatmentPLoS One2009411e769519907646

- NixonAJNeubergDHayesDFRelationship of patient age to pathologic features of the tumor and prognosis for patients with stage I or II breast cancerJ Clin Oncol19941258888948164038

- FowbleBLSchultzDJOvermoyerBThe influence of young age on outcome in early stage breast cancerInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys199430123338083119

- HanWKimSWParkIAYoung age: an independent risk factor for disease-free survival in women with operable breast cancerBMC Cancer200448215546499

- HanWKangSYKorean Breast Cancer SoceityRelationship between age at diagnosis and outcome of premenopausal breast cancer: age less than 35 years is a reasonable cut-off for defining young age-onset breast cancerBreast Cancer Res Treat2010119119320019350387

- SheridanWScottTCarolineSBreast cancer in young women: have the prognostic implications of breast cancer subtypes changed over time?Breast Cancer Res Treat2014147361762925209005

- MahmoodUMorrisCNeunerGSimilar survival with breast conservation therapy or mastectomy in the management of young women with early-stage breast cancerInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys20128351387139322300561

- KromanNHoltvegHWohlfahrtJEffect of breast-conserving therapy versus radical mastectomy on prognosis for young women with breast carcinomaCancer2004100468869314770422

- KurianAWLichtensztajnDYKeeganTHNelsonDOClarkeCAGomezSLUse of and mortality after bilateral mastectomy compared with other surgical treatments for breast cancer in California, 1998–2011JAMA2014312990291425182099

- PortschyPRKuntzKMTuttleTMSurvival outcomes after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a decision analysisJ Natl Cancer Inst20141068duj160

- MahmoodUHanlonALKoshyMIncreasing national mastectomy rates for the treatment of early stage breast cancerAnn Surg Oncol20132051436144323135312

- DidierFRadiceDGandiniSDoes nipple preservation in mastectomy improve satisfaction with cosmetic results, psychological adjustment, body image and sexuality?Breast Cancer Res Treat2009118362363319003526

- MetcalfeKACilTDSempleJLLong-term psychosocial functioning in women with bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: does preservation of the nipple-areolar complex make a difference?Ann Surg Oncol201522103324333026208581

- FisherBAndersonSBryantJTwenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancerN Engl J Med2002347161233124112393820

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative GroupDarbySMcGalePCorreaCEffect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trialsLancet201137898041707171622019144

- NSABP Foundation IncRadiation therapy (WBI versus PBI) in treating women who have undergone surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ or stage I or stage II breast cancer [cited August 30, 2015] Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00103181. NLM identifier: NCT00103181Accessed November 12, 2015

- ShahCViciniFWazerDEArthurDPatelRRThe American Brachytherapy Society consensus statement for accelerated partial breast irradiationBrachytherapy201312426727723619524

- The American Society of Breast Surgeons consensus statement for accelerated partial breast irradiation [cited August 30, 2015] Available from: https://www.breastsurgeons.org/statements/PDF_Statements/APBI.pdfAccessed November 12, 2015

- SmithBDArthurDWBuchholzTAAccelerated partial breast irradiation consensus statement from the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO)Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys2009744987100119545784

- BartelinkHMaingonPPoortmansPWhole-breast irradiation with or without a boost for patients treated with breast-conserving surgery for early breast cancer: 20-year follow-up of a randomised phase 3 trialLancet Oncol2015161475625500422

- SmithBDBentzenSMCorreaCRFractionation for whole breast irradiation: an American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) evidence-based guidelineInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys2011811596820638191

- OvergaardMJensenMBOvergaardJPostoperative radiotherapy in high-risk postmenopausal breast-cancer patients given adjuvant tamoxifen: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82c randomised trialLancet199935391651641164810335782

- OvergaardMHansenPSOvergaardJPostoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82b TrialN Engl J Med1997337149499559395428

- RagazJlivottoIASpinelliJJLocoregional radiation therapy in patients with high-risk breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: 20-year results of the British Columbia randomized trialJ Natl Cancer Inst200597211612615657341

- GargAKOhJLOswaldMJEffect of postmastectomy radiotherapy in patients <35 years old with stage II–III breast cancer treated with doxorubicin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy and mastectomyInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys20076951478148317855016

- WallgrenABonettiMGelberRDRisk factors for locoregional recurrence among breast cancer patients: results from International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I through VIIJ Clin Oncol20032171205121312663706

- JagsiRRaadRAGoldbergSLocoregional recurrence rates and prognostic factors for failure in node-negative patients treated with mastectomy: implications for postmastectomy radiationInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys20056241035103915990006

- YildirimEBerberogluUCan a subgroup of node-negative breast carcinoma patients with T1-2 tumor who may benefit from postmastectomy radiotherapy be identified?Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys20076841024102917398017

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative GroupEffects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trialsLancet200536594721687171715894097

- DaviesCPanHGodwinJLong-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trialLancet2013381986980581623219286

- GrayRGReaDHandleyKaTTom: Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years in 6,953 women with early breast cancerJ Clin Oncol201331suppl abstr 5

- PaganiOO’NeillACastiglioneMPrognostic impact of amenorrhoea after adjuvant chemotherapy in premenopausal breast cancer patients with axillary node involvement: results of the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) Trial VIEur J Cancer19983456326409713266

- International Breast Cancer Study GroupColleoniMGelberSGoldhirschATamoxifen after adjuvant chemotherapy for premenopausal women with lymph node-positive breast cancer: International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 13-93J Clin Oncol20062491332134116505417

- SwainSMJeongJHWolmarkNAmenorrhea from breast cancer therapy – not a matter of doseN Engl J Med2010363232268227021121855

- FrancisPAReganMMFlemingGFAdjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancerN Engl J Med2015372543644625495490

- PaganiOReganMMWalleyBAAdjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancerN Engl J Med2014371210711824881463

- BernhardJLuoWRibiKPatient-reported outcomes with adjuvant exemestane versus tamoxifen in premenopausal women with early breast cancer undergoing ovarian suppression (TEXT and SOFT): a combined analysis of two phase 3 randomised trialsLancet Oncol201516784885826092816

- Piccart-GebhartMJProcterMLeyland-JonesBTrastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancerN Engl J Med2005353161659167216236737

- PerezEASumanVJDavidsonNESequential versus concurrent trastuzumab in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancerJ Clin Oncol201129344491449722042958

- RomondEHPerezEABryantJTrastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancerN Engl J Med2005353161673168416236738

- SlamonDEiermannWRobertNAdjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancerN Engl J Med2011365141273128321991949

- BaselgaJCortésJKimSBPertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancerN Engl J Med2012366210911922149875

- SchneeweissAChiaSHickishTPertuzumab plus trastuzumab in combination with standard neoadjuvant anthracycline-containing and anthracycline-free chemotherapy regimens in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a randomized phase II cardiac safety study (TRYPHAENA)Ann Oncol20132492278228423704196

- GianniLPienkowskiTImYHEfficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trialLancet Oncol2012131253222153890

- ChristinatAPaganiOFertility after breast cancerMaturitas201273319119623020991

- Rodriguez-WallbergKAOktayKOptions on fertility preservation in female cancer patientsCancer Treat Rev201238535436122078869

- RonnRHolzerHEOncofertility in Canada: the impact of cancer on fertilityCurr Oncol2013204e338e34423904772

- WalsheJMDenduluriNSwainSMAmenorrhea in premenopausal women after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200624365769577917130515

- DonnezJDolmansMMFertility preservation in womenNat Rev Endocrinol201391273574924166000

- LorenAWManguPBBeckLNFertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline updateJ Clin Oncol201331192500251023715580

- FriedlerSKocOGidoniYRazielARon-ElROvarian response to stimulation for fertility preservation in women with malignant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisFertil Steril201297112513322078784

- MooreHCUngerJMPhillipsKAGoserelin for ovarian protection during breast-cancer adjuvant chemotherapyN Engl J Med20153721092393225738668

- AzimHAJrSantoroLPavlidisNSafety of pregnancy following breast cancer diagnosis: a meta-analysis of 14 studiesEur J Cancer2011471748320943370

- AzimHAJrKromanNPaesmansMPrognostic impact of pregnancy after breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status: a multicenter retrospective studyJ Clin Oncol2013311737923169515

- KromanNJensenMBWohlfahrtJEjlertsenBDanish Breast Cancer Cooperative GroupPregnancy after treatment of breast cancer – a population-based study on behalf of Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative GroupActa Oncol200847454554918465320

- ValachisATsaliLPesceLLSafety of pregnancy after primary breast carcinoma in young women: a meta-analysis to overcome bias of healthy mother effect studiesObstet Gynecol Surv2010651278679321411023

- International Breast Cancer Study GroupPregnancy Outcome and Safety of Interrupting Therapy for Women With Endocrine Responsive Breast Cancer (POSITIVE) [cited August 17, 2015] Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02308085?term=02308085&rank=1. NLM identifier: NCT02308085Accessed November 12, 2015

- PaganiOAzimHJrPregnancy after breast cancer: myths and factsBreast Care (Basel)20127321021422872794

- AzimHAJrMetzger-FilhoOde AzambujaEPregnancy occurring during or following adjuvant trastuzumab in patients enrolled in the HERA trial (BIG 01-01)Breast Cancer Res Treat2012133138739122367645

- SaundersCMBaumMBreast cancer and pregnancy: a reviewJ R Soc Med19938631621658155095

- AndersonJMMammary cancers and pregnancyBr Med J19791617111241127376044

- NoyesRDSpanosWJJrMontagueEDBreast cancer in women aged 30 and underCancer1982496130213076174202

- VashiRHooleyRButlerRGeiselJPhilpottsLBreast imaging of the pregnant and lactating patient: imaging modalities and pregnancy-associated breast cancerAJR Am J Roentgenol2013200232132823345353

- HeymannJJHalliganAMHodaSAFaceyKEHodaRSFine needle aspiration of breast masses in pregnant and lactating women: experience with 28 cases emphasizing Thinprep findingsDiagn Cytopathol201543318819424976078

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric PracticeACOG Committee Opinion. Number 299, September 2004 (replaces No 158, September 1995). Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancyObstet Gynecol2004104364765115339791

- BuralGGLaymonCMMountzJMNuclear imaging of a pregnant patient: should we perform nuclear medicine procedures during pregnancy?Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther20122111523487481

- ToescaAGentiliniOPeccatoriFAzimHAJrAmantFLocoregional treatment of breast cancer during pregnancyGynecol Surg201411427928425419205

- ChenZKingWPearceyRKerbaMMackillopWJThe relationship between waiting time for radiotherapy and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of the literatureRadiother Oncol200887131618160158

- MazonakisMVarverisHDamilakisJTheoharopoulosNGourtsoyiannisNRadiation dose to conceptus resulting from tangential breast irradiationInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200355238639112527052

- GentiliniOCremonesiMToescaASentinel lymph node biopsy in pregnant patients with breast cancerEur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging2010371788319662412

- GropperABCalvilloKZDominiciLSentinel lymph node biopsy in pregnant women with breast cancerAnn Surg Oncol20142182506251124756813

- RingAESmithIEJonesAShannonCGalaniEEllisPAChemotherapy for breast cancer during pregnancy: an 18-year experience from five London teaching hospitalsJ Clin Oncol200523184192419715961766

- HahnKMJohnsonPHGordonNTreatment of pregnant breast cancer patients and outcomes of children exposed to chemotherapy in uteroCancer200610761219122616894524

- BerryDLTheriaultRLHolmesFAManagement of breast cancer during pregnancy using a standardized protocolJ Clin Oncol199917385586110071276

- MurthyRKTheriaultRLBarnettCMOutcomes of children exposed in utero to chemotherapy for breast cancerBreast Cancer Res201416650025547133

- ZagouriFSergentanisTNChrysikosDPapadimitriouCADimopoulosMABartschRTrastuzumab administration during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysisBreast Cancer Res Treat2013137234935723242615

- ShapiroCLHalabiSHarsVZoledronic acid preserves bone mineral density in premenopausal women who develop ovarian failure due to adjuvant chemotherapy: final results from CALGB trial 79809Eur J Cancer201147568368921324674

- SverrisdottirAFornanderTJacobssonHvon SchoultzERutqvistLEBone mineral density among premenopausal women with early breast cancer in a randomized trial of adjuvant endocrine therapyJ Clin Oncol200422183694369915365065

- GnantMMlineritschBLuschin-EbengreuthGAdjuvant endocrine therapy plus zoledronic acid in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: 5-year follow-up of the ABCSG-12 bone-mineral density substudyLancet Oncol20089984084918718815

- BrufskyAMHarkerWGBeckJTFinal 5-year results of Z-FAST trial: adjuvant zoledronic acid maintains bone mass in postmenopausal breast cancer patients receiving letrozoleCancer201211851192120121987386

- SmithMREgerdieBHernández TorizNDenosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancerN Engl J Med2009361874575519671656

- EllisGKBoneHGChlebowskiRRandomized trial of denosumab in patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for nonmetastatic breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200826304875488218725648

- GnantMFMlineritschBLuschin-EbengreuthGZoledronic acid prevents cancer treatment-induced bone loss in premenopausal women receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy for hormone-responsive breast cancer: a report from the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study GroupJ Clin Oncol200725782082817159195

- ColemanRCameronDDodwellDAdjuvant zoledronic acid in patients with early breast cancer: final efficacy analysis of the AZURE (BIG 01/04) randomised open-label phase 3 trialLancet Oncol2014159997100625035292

- GnantMPfeilerGDubskyPCAdjuvant denosumab in breast cancer (ABCSG-18): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2015386999243344326040499

- American Cancer SocietyBreast Cancer Facts and Figures 2015–2016Atlanta, CAAmerican Cancer Society2015