?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

High levels of dental caries, challenging child behavior, and parent expectations support a need for sedation in pediatric dentistry. This paper reviews modern developments in pediatric sedation with a focus on implementing techniques to enhance success and patient safety. In recent years, sedation for dental procedures has been implicated in a disproportionate number of cases that resulted in death or permanent neurologic damage. The youngest children and those with more complicated medical backgrounds appear to be at greatest risk. To reduce complications, practitioners and regulatory bodies have supported a renewed focus on health care quality and safety. Implementation of high fidelity simulation training and improvements in patient monitoring, including end-tidal carbon dioxide, are becoming recognized as a new standard for sedated patients in dental offices and health care facilities. Safe and appropriate case selection and appropriate dosing for overweight children is also paramount. Oral sedation has been the mainstay of pediatric dental sedation; however, today practitioners are administering modern drugs in new ways with high levels of success. Employing contemporary transmucosal administration devices increases patient acceptance and sedation predictability. While recently there have been many positive developments in sedation technology, it is now thought that medications used in sedation and anesthesia may have adverse effects on the developing brain. The evidence for this is not definitive, but we suggest that practitioners recognize this developing area and counsel patients accordingly. Finally, there is a clear trend of increased use of ambulatory anesthesia services for pediatric dentistry. Today, parents and practitioners have become accustomed to children receiving general anesthesia in the outpatient setting. As a result of these changes, it is possible that dental providers will abandon the practice of personally administering large amounts of sedation to patients, and focus instead on careful case selection for lighter in-office sedation techniques.

Introduction

The developing child often lacks the coping skills necessary to navigate the dental experience, making provision of quality dental care to children challenging. While unrestored caries may contribute to pain, disordered sleep, difficulty learning, and poor growth in children, unpleasant dental experiences can cause psychologic harm.Citation1–Citation3 Most dental anxiety develops in childhood as a result of frightening and painful dental experiences. If appropriate precautions are not taken, dental treatment may overwhelm the child, resulting in dental fear and avoidance.Citation4 These fears persist into adulthood, causing 10%–20% of the US population to avoid necessary dental care.Citation5,Citation6 Sedation reduces such complications and instills trust in the family and child.

Today, it is estimated that 100,000–250,000 pediatric dental sedations are performed each year in the USA, and practitioners anticipate a need for more pharmacologic behavior management in the future.Citation7,Citation8 High levels of pediatric dental disease, increasingly difficult child behavior, and parent expectations support a need for sedation services.Citation8–Citation11 Here we review common challenges that contemporary dental practitioners experience and suggest possible solutions.

Risk factors for adverse events

Sedation is a continuum. Physiologic effects vary significantly depending upon a variety of factors, including medication, dose, delivery route, and patient characteristics.Citation12,Citation13 Minimal sedation is considered to be the mildest form of sedation. As stronger medications and higher doses are administered, the depth of sedation shifts toward moderate sedation, deep sedation, and possibly even general anesthesia. At more profound levels, patients become unresponsive and incapable of maintaining their own breathing or cardiovascular function.Citation14,Citation15 In adult dental practice, titration of sedation depth through intravenous drug administration is common. In pediatrics, however, due to behavioral constraints, sedation by bolus oral administration is well tolerated and routine.Citation7,Citation13 With oral administration, sedation depth can be difficult to predict and titration is not possible.Citation16 Consequently, over-sedation and respiratory obstruction can occur. Should this happen, it is the responsibility of the sedation provider to manage the unconscious child until she or he regains the ability to self-regulate.

Sedation for dental procedures has been implicated in a disproportionate number of cases that resulted in death or permanent neurologic damage.Citation17–Citation19 When causes of sedation-related injury and death in outpatient settings have been reviewed, damage almost always resulted from an inability to resuscitate once a patient lost protective reflexes.Citation17,Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 Children under 5 years of age and those with pre-existing medical conditions appear to be at greatest risk.Citation17,Citation18,Citation21 These findings have led to increased scrutiny of pediatric dental sedation by the public and the medical community.Citation20,Citation22 One concern is that dentists and other non-anesthesiologist practitioners receive varying levels of sedation training and often do not practice in settings with immediate access to rescue resources such as a code team. In contrast, anesthesiologists receive relatively uniform training and practice the skills required to rescue patients on a daily basis. They also commonly practice in an operating room environment and have the ability to request backup when needed.

Patient monitoring

Early efforts to provide sedation in the dental office were largely unregulated, and clinicians primarily relied only on direct physical findings such as quality of respiration and patient color to assess the sedated patient. Over time technology improved, and professional associations and regulatory bodies provided a framework for safe and effective practice.Citation16,Citation23,Citation24 Advancements included monitoring patients with blood pressure monitors and precordial stethoscopes. With the advent of pulse oximetry, electronic monitoring of blood oxygen saturation further increased safety. This allowed for continuous monitoring of heart rate and blood oxygen saturation, with alarm activation when blood pressure or oxygenation declined below a threshold value. In contemporary practice, end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) monitors have become standard in operating rooms to monitor apnea and hypoventilation.

In response to growing safety concerns, EtCO2 monitoring is now used increasingly in ambulatory settingsCitation17,Citation18,Citation20,Citation25 (). Professional association guidelines reflect this trend, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists has amended its standards for basic anesthetic monitoring to require EtCO2 for moderate or deep sedation.Citation25 In dentistry, perhaps the most widely recognized professional sedation guidelines come from the American Dental Association. For children 12 years of age and under, the American Dental Association recognizes the American Academy of Pediatrics/American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAP/AAPD) guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Both the American Dental Association and the AAP/AAPD guidelines suggest that EtCO2 monitoring may be used to evaluate respiration; however, it is not currently required for moderate sedation.Citation16,Citation26 In the USA, each state has unique requirements for a dentist to perform sedation. States vary considerably regarding training standards, required continuing education, and advanced life support credentials required to maintain a sedation permit.Citation27 Similarly, there is no nationally recognized government standard for monitoring of dental patients during sedated procedures. However, some states have begun to mandate the use of EtCO2 monitors for dental sedation. Given this trend, it is possible that in the future EtCO2 monitoring will become the standard for sedated patients in dental offices and health care facilities.

Modern drugs and routes

Selection of medications is a critical component of the sedation plan. When possible, consideration should be given to sedatives with available reversal agents. In the event of oversedation, benzodiazepine and narcotic medications may be preferred over drugs without known reversal agents, such as chloral hydrate. In recent years, both the solution and capsule form of chloral hydrate have been withdrawn from the US market. In the future, in spite of its historic success, chloral hydrate will likely continue to fall out of favor for pediatric dental sedation.

Oral sedation is the most popular route of administration among pediatric dentists.Citation28,Citation29 However, this route is notoriously unpredictable, and frustration often arises when children refuse to accept the sedative medication.Citation28,Citation30 Efforts have been made to mask the bitter taste of the oral medications; however, it is not uncommon for children to spit or regurgitate them. On the other hand, placement of an intravenous cannula for parenteral sedation can be traumatic to children.Citation30 New methods of medication delivery have been proposed and investigated. One alternative is the transmucosal (intranasal, sublingual, buccal) route. The benefits of this route include direct absorption of drugs into the systemic circulation, avoidance of hepatic first pass metabolism, increased bioavailability, and faster onset compared with oral sedation. Transmucosal administration also results in less discomfort than intravenous sedation and better acceptance by patients.Citation28

Intranasal administration of midazolam has been proven to be a safe and effective sedative for short procedures and is widely used by pediatric dentists.Citation29–Citation36 In addition to quick onset, a relatively quick recovery has also been suggested.Citation34 Some believe that another possible advantage of intranasal sedation is that a strict adherence to fasting requirements may not be essential.Citation28,Citation32,Citation37 This is a controversial area; however, results of clinical trials suggest that children may be given intranasal midazolam with less risk of nausea, vomiting, and respiratory complications.Citation32,Citation37 While practitioners should be cautious in relaxing recognized safety standards, given the appropriate setting (such as a hospital emergency room), this technique may prove useful for uncooperative children who need emergency treatment and have eaten.

Although intranasal administration is usually simple, relatively painless, and requires less patient cooperation, it has been associated with mucosal irritation. This may lead to coughing, sneezing, crying and the expulsion of part of the dose. This is particularly true when a large volume of the drug is applied.Citation34,Citation36 Therefore, careful administration is critical. When administration of intranasal midazolam by drop and aerosolized form were compared, aerosolization was better tolerated and led to less aversive behaviorCitation29 ().

Nasal mucosal secretions can also affect intranasal drug absorption. The buccal mucosa has a rich blood supply and is relatively permeable, yielding pharmacokinetics that are similar to intranasal administration. It therefore appears to be an attractive alternative to the intranasal route.Citation38 Buccal administration of aerosolized midazolam has been proven to be safe, effective, and well accepted by young patients.Citation28,Citation39,Citation40 An oral solution may also be used in place of aerosol spray; however, the possibility of experiencing the bitter taste increases, leading to poor patient acceptance.Citation40 Buccal and intranasal midazolam have the same maximum working time while intranasal has a faster onset time. Intranasal midazolam also elicited less crying and produced a greater proportion of patients with optimal sedation scores.Citation41 Chopra et al and Klein et al reported better acceptance of the buccal route,Citation28,Citation39 while Sunbul et al found intranasal midazolam to be more acceptable to children.Citation41 Interestingly, even though it was poorly tolerated by subjects during administration, in one study a greater proportion of parents preferred the intranasal route for future sedation.Citation39

Dexmedetomidine is a selective alpha2-adrenergic agonist that provides sedative, anxiolytic, and analgesic properties without causing respiratory depression.Citation42,Citation43 It was approved by US Food and Drug Administration to be used for sedation in adults in the intensive care setting in 1999. Due to its efficacy in adults, in recent years it has been introduced into the pediatric population for procedural sedation outside the operating room. Dexmedetomidine is available in intranasal, buccal, or oral form.Citation43 The safe use of dexmedetomidine in pediatric diagnostic radiology has been well documented.Citation42 However, studies on its use for outpatient dental procedures are limited, especially in children. In a pilot study by Hitt et al, intranasal delivery of sufentanil and dexmedetomidine provided acceptable sedation without respiratory depression or major complications in 20 children undergoing dental procedures.Citation44

When reviewing the small clinical trials and observational studies exploring pediatric use of dexmedetomidine, it is important to note that all these studies were performed in a medically controlled setting under the supervision of anesthesiologists.Citation44–Citation46 Clearly, much work needs to be done to define the efficacy of dexmedetomidine and its impact on pediatric dental sedation. However, due to its unique characteristics and lack of respiratory depression, this medication holds great promise as an alternative option for sedation in the pediatric dental clinic.

Optimizing care for patient safety

Risk is inherent in procedural sedation. While it is impossible to eliminate risk entirely, negative outcomes can be minimized by optimizing work systems and eliminating human factors for error.Citation47–Citation49 We also reduce the chance of future incidents by recognizing accidents that were avoided but nearly occurred. These “near misses” should be reported so that contributing factors can be analyzed and eliminated.Citation50

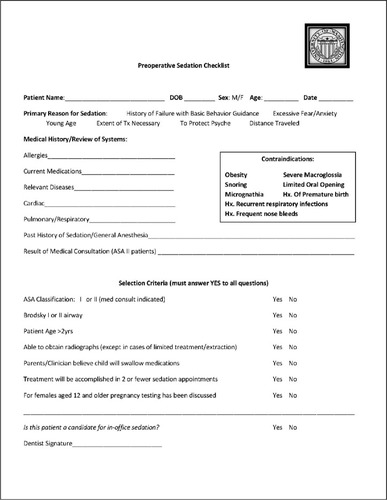

The greatest successes are achieved by focusing on safety before the sedation appointment. Preparation begins with appropriate case selection. Using a standard form for presedation, patient assessment helps eliminate guesswork (). Appropriate assessment includes patient medical history, physical examination (including targeted airway assessment), and assignment of an American Society of Anesthesiologists score.Citation51,Citation52 Similarly, in-office sedation should be limited to healthy children. Healthy children and those with mild systemic disease (American Society of Anesthesiologists score I and II) can generally be cared for safely and effectively in the dental clinic. Complicated medical conditions including heart disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity have been shown to increase sedation risk and the chances of failed sedation.Citation53 These factors must be considered carefully when selecting the sedation regimen and venue.

Figure 3 A presedation checklist.Citation13

Abbreviations: Hx, history; Tx, treatment; M, male; F, female; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

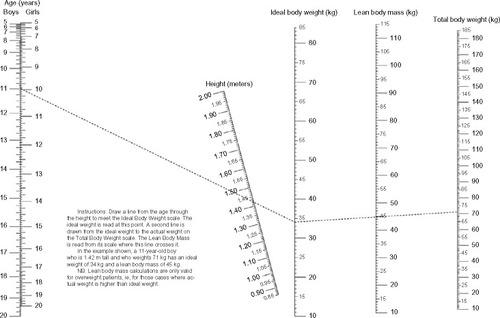

Appropriate dosing is another concern. In the USA, approximately one-third of children aged 2–19 years are overweight or obese. This represents more than a three-fold increase in childhood obesity over the past 30 years.Citation54 In an analysis of perioperative complications, overweight and obese children had a higher incidence of difficult airway, upper airway obstruction, and longer postoperative recovery period.Citation55 Obese children are also much more likely to have obstructive sleep apnea.Citation56 If total body weight (TBW) is used for dose calculation, overweight children are at risk for overdose. Some authors suggest that dosing should be based upon ideal body weight (IBW) or lean body mass (LBM), although there is a lack of clear guidance in this area.Citation57–Citation59 Calculating IBW and LBM in children can be relatively complicated, and validity of the measurement is lost as the child grows. Simplified weight calculations for children are expressed in the following equations:Citation57,Citation59

Although this provides some guidance in dosing overweight children, in many circumstances calculation of appropriate dosing using this method may not be practical. It should also be remembered that when a child’s actual weight is less than IBW or LBM, the lower figure should be used. An alternative nomographic method has recently been described for use in children aged 5 years and older.Citation60 A nomograph is constructed by placing scales for known variables (ie, age, height, TBW) side by side. Known values are then plotted on each scale. The value of an unknown variable (LBM) is determined by the drawing a straight line from the points plotted on each scale. The point where the lines intersect the unknown variable scale is an approximation of its value (). This method allows clinicians to quickly calculate LBM using a chart. One needs only to know the child’s age, height, and TBW. While still an ongoing area of study, researchers anticipate development of nomographic charts that are validated for children under age 5 years and incorporation of the tool into a smartphone application.

Figure 4 A novel body mass nomogram used for calculating lean body mass in children.

Following the sedation appointment, uniform discharge criteria ensure that the child is not sent home before she or he is ready to leave direct medical supervision. A number of studies have suggested that children who are sedated for dental care routinely experience prolonged sleepiness and difficulty waking, including sleeping in the car while riding home after treatment.Citation61,Citation62 While tiredness can be expected following the sedation appointment, implementation of discharge criteria helps to ensure that the child is not excessively sedated when they leave the dental office. If a child is able to achieve a University of Michigan Sedation Scale score of 0 or 1 (0, awake and alert or minimally sedated; 1, tired/sleepy, appropriate response to verbal conversation and/or sound) and able to stay awake for 20 minutes when undisturbed (the Modified Maintenance of Wakefulness Test), she or he is generally considered to be ready to return home with parental supervision.Citation63,Citation64

Simulation training is increasingly being recognized as an important mechanism for improving health care quality and safety. Basic simulation can be as simple as regularly practicing emergency skills with office staff. Advanced simulation programs provide a means of practicing low frequency events using high-fidelity clinical environments and mannequins that accurately reproduce physiologic conditions (). When simulation is incorporated into education it increases knowledge, clinical skills, and judgment more than lecture-only teaching.Citation65,Citation66 Simulation is also thought to be a reliable method of teaching non-emergency sedation skills, such as presedation assessment, and it is becoming an increasingly common adjunct to sedation education programs.Citation67

Anesthesia neurotoxicity

In recent years, it has been suggested that medications used in sedation and anesthesia may have adverse effects on the developing brain.Citation68–Citation70 Initial research demonstrated harm to the brains of young animals.Citation71–Citation74 This raised concern that young children might also be at risk when exposed to anesthetic agents.Citation75 Following the publication of these concerning findings, human studies were initiated.Citation76–Citation79 The results have often revealed conflicting conclusions, with some showing long-term deficits in learning and behavior while others have not.Citation80 This is a difficult area of study, because children who receive sedation and anesthesia commonly have pathologic conditions for which they require surgery. They may therefore be fundamentally distinct from their healthy peers. Adverse neurologic outcomes are also difficult to recognize and measure. Investigation into these findings continues, and poses a significant challenge to resources and study design. While it will likely be many years before we are able to determine the neurologic effects of sedation and anesthesia drugs with confidence, this is an area that providers must be familiar with. We do not definitively know the long-term effects of these drugs, so we must exercise judgment in recommending these services to pediatric patients. Parents should be informed of procedural risks and benefits, and sedation must only be employed when a significant benefit to the patient can be expected.

Increasing sedation success

A number of sedation rating scales have been used to evaluate sedation quality and child behavior. According to a recent review of the pediatric dental sedation literature, the Houpt Behavior Rating Scale (HBRS) has been used most frequently in research.Citation81 The advantage of the HBRS is that it allows for evaluation of sedation depth, the child’s behavior, and an overall rating of the visit (). One disadvantage of this rating system is that the measure of success focuses primarily on the clinician’s ability to complete treatment. While clearly central to the HBRS, this characteristic is found in many other common sedation scales, including the Frankl, Ramsay, and Ohio State University Behavior Rating Scale.Citation82–Citation85 A number of authors have suggested that outcome assessment should be more patient-focused. This recognizes that the intent of sedation is not only to complete a procedure with minimal movement and crying, but also that the child leaves with a positive impression of dental care.Citation81,Citation86

Table 1 Houpt Behavior Rating Scale

When considering lighter sedation techniques, case selection becomes increasingly important.Citation87 Child temperament or “behavioral style” is one factor associated with success in procedural sedation. Temperament has been defined as “[…] constitutional differences in reactivity and regulation […] influenced over time by heredity, maturation, and experience”.Citation88 Since the 1950s, a number of instruments have been used to evaluate child temperament. While measures vary in the literature, research has elucidated the type of child temperament associated with positive sedation outcomes. Characteristics such as emotionality, impulsivity, inflexibility, shyness, and difficulty dealing with new situations appear to be associated with sedation failure.Citation89–Citation91 Conversely, adaptability, persistence, and the ability to self-regulate may be associated with increased likelihood of success.Citation92,Citation93 Therefore, when considering a child for sedation, pay close attention to the behavior of the child during the consultation visit. Children who are shy, cling to parents, have difficulty tolerating simple tasks (such as dental prophylaxis or radiographs), and are unwilling to interact with the clinician may be better suited for alternative methods of behavior guidance, including general anesthesia or delayed treatment.

Children who receive mild to moderate sedation are expected to be awake and responsive to direction from the treating dentist. Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians employ their best non-pharmacologic behavior management skills with sedated patients.Citation13 While these skills are generally regarded as a core competency of pediatric dentistry, they are increasingly being recognized as important in the medical literature as well.Citation94–Citation98 Interventions such as distraction have been shown to decrease anxiety and pain perception in non-sedated patients.Citation99 When effectively incorporated into the sedation scheme, a combined pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic technique was also more effective at reducing child distress than pharmacologic techniques alone.Citation100 Non-pharmacologic methods may be particularly effective for sedated young children with active imaginations. Also, because adequate sedation requires both anxiety reduction and pain control, excellent local anesthesia is critical. A child with profound analgesia is much more likely to be in a state of mind that facilitates good sedation.

Increasing role of dental anesthesia

Today’s sedation practitioner faces significant challenges to achieve the described levels of child-centered care. Reports indicate that while child behavior in the dental office is becoming more difficult, parents are becoming increasingly particular about their child’s experience.Citation8,Citation101,Citation102 At the same time, concerns about child safety during sedation procedures have drawn scrutiny of sedation performed by dental practitioners in the office setting. The use of general anesthesia for pediatric dental treatment has grown accordingly. Surveys indicate that over the past 30 years parents have become much more accepting of general anesthesia for dental treatment.Citation103 This may be due to the public’s familiarity with anesthesia performed in surgery centers and other outpatient facilities. While in the past, nearly all dental surgery was provided in the hospital setting, today dentists are incorporating outpatient anesthesia services into their private offices.Citation102,Citation104 With the increased availability of ambulatory anesthesia services, general anesthesia in the dental clinic has become a safe and cost-effective mechanism to deliver dental care to healthy children. Consequently, it is possible that in the future we will see a trend toward lighter in-office sedation. In turn, for larger cases and more difficult patients, general anesthesia may replace deeper sedation techniques.

Conclusion

Providing quality dental care to young children can be a challenge. Pediatric dental sedation allows the clinician to provide treatment in a way that is minimally traumatic and preserves the child’s trust. Although sedation is an effective tool to manage pediatric anxiety, adverse treatment outcomes and increased regulatory scrutiny have made this a contentious area. Therefore, practitioners should strive to reduce patient risk by carefully selecting patients who are medically optimized for sedation and instilling a culture of safety into clinical practice. Given parent preferences and high levels of pediatric dental disease, it is likely that we will see the need for sedation continue to grow in the future. This is an exciting opportunity to increase sedation success by refining behavioral selection parameters, utilizing modern drugs and routes, and employing the services of anesthesiologists in outpatient settings.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SheihamADental caries affects body weight, growth and quality of life in pre-schoolBr Dent J200620162562617128231

- BergJSlaytonREarly Childhood Oral Health1st edHoboken, NJ, USAWiley–Blackwell2009

- EdelsteinBVargasCCandelariaDVemuriMExperience and policy implications of children presenting with dental emergencies to US pediatric dentistry training programsPediatr Dent20062843143717036709

- LockerDLiddellADempsterLShapiroDAge of onset of dental anxietyJ Dent Res19997879079610096455

- MilgromPNewtonJTBoyleCHeatonLJDonaldsonNThe effects of dental anxiety and irregular attendance on referral for dental treatment under sedation within the National Health Service in LondonCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol20103845345920545723

- MilgromPFisetLMelnickSWeinsteinPThe prevalence and practice management consequences of dental fear in a major US cityJ Am Dent Assoc19881166416473164029

- WilsonSPharmacological management of the pediatric dental patientPediatr Dent20042613113615132275

- CasamassimoPSWilsonSGrossLEffects of changing US parenting styles on dental practice: perceptions of diplomates of the American Board of Pediatric Dentistry presented to the College of Diplomates of the American Board of Pediatric Dentistry 16th Annual Session, Atlanta, Ga, Saturday, May 26, 2001Pediatr Dent200224182211874053

- KasteLMDruryTFHorowitzAMBeltranEAn evaluation of NHANES III estimates of early childhood cariesJ Public Health Dent19995919820010649592

- DyeBATanSSmithVTrends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004Vital Health Stat 112007192

- EdelsteinBLDouglassCWDispelling the myth that 50 percent of US schoolchildren have never had a cavityPublic Health Rep19951105225307480606

- WilkinsonGRDrug metabolism and variability among patients in drug responseN Engl J Med20053522211222115917386

- NelsonTNelsonGThe role of sedation in contemporary pediatric dentistryDent Clin North Am20135714516123174615

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare OrganizationsRevisions to anesthesia care standards. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Ambulatory Care2012 Available from http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CB8QFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.jointcommission.org%2Fassets%2F1%2F18%2F2011_ahc_hdbk.pdf&ei=MyWgVY3nPNb6oQSX85CQCw&usg=AFQjCNFLGu_ST4go7xbcMEW5IFXnwP3U_w&sig2=JBHPPDxeRDJ0AomJjRNvRQ&bvm=bv.97653015,d.cGU

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare OrganizationsComprehensive Accreditation Manual for HospitalsOakbrook, IL, USAJoint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations2000

- American Academy on Pediatrics; American Academy on Pediatric DentistryGuideline for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic proceduresPediatr Dent20083014315919216414

- CoteCJNottermanDAKarlHWWeinbergJAMcCloskeyCAdverse sedation events in pediatrics: a critical incident analysis of contributing factorsPediatrics200010580581410742324

- ChickaMCDemboJBMathu-MujuKRNashDABushHMAdverse events during pediatric dental anesthesia and sedation: a review ofPediatr Dent20123423123822795157

- CostaLRCostaPSBrasileiroSVBendoCBViegasCMPaivaSMPost-discharge adverse events following pediatric sedation with high doses of oral medicationJ Pediatr201216080781322133425

- CraveroJPBlikeGTBeachMIncidence and nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation/anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room: report from the Pediatric Sedation Research ConsortiumPediatrics20061181087109616951002

- LeeHHMilgromPStarksHBurkeWTrends in death associated with pediatric dental sedation and general anesthesiaPaediatr Anaesth20132374174623763673

- CraveroJPBlikeGTPediatric anesthesia in the nonoperating room settingCurr Opin Anaesthesiol20061944344916829729

- Committee on DrugsAmerican Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: addendumPediatrics200211083683812359805

- No authors listedAmerican Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs: Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic proceduresPediatrics199289111011151594358

- WeaverJThe latest ASA mandate: CO(2) monitoring for moderate and deep sedationAnesth Prog20115811111221882985

- American Dental AssociationGuidelines for the use of sedation and general anesthesia by dentists2012 Available from: http://www.ada.org/∼/media/ADA/About%20the%20ADA/Files/anesthesia_use_guidelines.ashxAccessed June 19, 2015

- LaPointeLGuelmannMPrimoschRState regulations governing oral sedation in dental practicePediatr Dent20123448949223265167

- ChopraRMittalMBansalKChaudhuriPBuccal midazolam spray as an alternative to intranasal route for conscious sedation in pediatric dentistryJ Clin Pediatr Dent20133817117324683783

- PrimoschREGuelmannMComparison of drops versus spray administration of intranasal midazolam in two- and three-year-old children for dental sedationPediatr Dent20052740140816435641

- BahetwarSKPandeyRKSaksenaAKChandraGA comparative evaluation of intranasal midazolam, ketamine and their combination for sedation of young uncooperative pediatric dental patients: a triple blind randomized crossover trialJ Clin Pediatr Dent20113541542022046702

- PrimoschREBenderFFactors associated with administration route when using midazolam for pediatric conscious sedationASDC J Dent Child20016823323811862873

- Al-RakafHBelloLLTurkustaniAAdenubiJOIntra-nasal midazolam in conscious sedation of young paediatric dental patientsInt J Paediatr Dent200111334011309871

- HartgravesPMPrimoschREAn evaluation of oral and nasal midazolam for pediatric dental sedationASDC J Dent Child1994611751818089345

- FukutaOBrahamRLYanaseHKurosuKThe sedative effects of intranasal midazolam administration in the dental treatment of patients with mental disabilities. Part 2: optimal concentration of intranasal midazolamJ Clin Pediatr Dent1994182592657811656

- FukutaOBrahamRLYanaseHAtsumiNKurosuKThe sedative effect of intranasal midazolam administration in the dental treatment of patients with mental disabilities. Part 1. The effect of a 0.2 mg/kg doseJ Clin Pediatr Dent1993172312378217888

- FuksABKaufmanERamDHovavSShapiraJAssessment of two doses of intranasal midazolam for sedation of young pediatric dental patientsPediatr Dent1994163013057937264

- ChopraRMarwahaMAssessment of buccal aerosolized midazolam for pediatric conscious sedationJ Investig Clin Dent201564044

- SchwagmeierRAlincicSStriebelHWMidazolam pharmacokinetics following intravenous and buccal administrationBr J Clin Pharmacol1998462032069764959

- KleinEJBrownJCKobayashiAOsincupDSeidelKA randomized clinical trial comparing oral, aerosolized intranasal, and aerosolized buccal midazolamAnn Emerg Med20115832332921689865

- Tavassoli-HojjatiSMehranMHaghgooRTohid-RahbariMAhmadiRComparison of oral and buccal midazolam for pediatric dental sedation: a randomized, cross-over, clinical trial for efficacy, acceptance and safetyIran J Pediatr20142419820625535540

- SunbulNDelviMBZahraniTASalamaFBuccal versus intranasal midazolam sedation for pediatric dental patientsPediatr Dent20143648348825514077

- MasonKPSedation trends in the 21st century: the transition to dexmedetomidine for radiological imaging studiesPaediatr Anaesth20102026527220015137

- McMorrowSPAbramoTJDexmedetomidine sedation: uses in pediatric procedural sedation outside the operating roomPediatr Emerg Care20122829229622391930

- HittJMCorcoranTMichienziKCreightonPHeardCAn evaluation of intranasal sufentanil and dexmedetomidine for pediatric dental sedationPharmaceutics2014617518424662315

- CimenZSHanciASivrikayaGUKilincLTErolMKComparison of buccal and nasal dexmedetomidine premedication for pediatric patientsPaediatr Anaesth20132313413822985207

- ZubDBerkenboschJWTobiasJDPreliminary experience with oral dexmedetomidine for procedural and anesthetic premedicationPaediatr Anaesth20051593293816238552

- CooperJBNewbowerRSKitzRJAn analysis of major errors and equipment failures in anesthesia management: considerations for prevention and detectionAnesthesiology19846034426691595

- GabaDMHuman error in anesthetic mishapsInt Anesthesiol Clin1989271371472670768

- HoffmanGMNowakowskiRTroshynskiTJBerensRJWeismanSJRisk reduction in pediatric procedural sedation by application of an American Academy of Pediatrics/American Society of Anesthesiologists process modelPediatrics200210923624311826201

- MasonKPGreenSMPiacevoliQAdverse event reporting tool to standardize the reporting and tracking of adverse events during procedural sedation: a consensus document from the World SIVA International Sedation Task ForceBr J Anaesth2012108132022157446

- ShannonMAlbersGBurkhartKSafety and efficacy of flumazenil in the reversal of benzodiazepine-induced conscious sedation. The Flumazenil Pediatric Study GroupJ Pediatr19971315825869386663

- RamaiahRBhanankerSPediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room: anticipating, avoiding and managing complicationsExpert Rev Neurother20111175576321539491

- GrunwellJRMcCrackenCFortenberryJStockwellJKamatPRisk factors leading to failed procedural sedation in children outside the operating roomPediatr Emerg Care20143038138724849275

- OgdenCLCarrollMDKitBKFlegalKMPrevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010JAMA201230748349022253364

- NafiuOOReynoldsPIBamgbadeOATremperKKWelchKKasa-VubuJZChildhood body mass index and perioperative complicationsPaediatr Anaesth20071742643017474948

- TanHLGozalDKheirandish-GozalLObstructive sleep apnea in children: a critical updateNat Sci Sleep2013510912324109201

- KendrickJGCarrRREnsomMHPharmacokinetics and drug dosing in obese childrenJ Pediatr Pharmacol Ther2010159410922477800

- IngrandeJBrodskyJBLemmensHJLean body weight scalar for the anesthetic induction dose of propofol in morbidly obese subjectsAnesth Analg2011113576220861415

- IngrandeJLemmensHJDose adjustment of anaesthetics in the morbidly obeseBr J Anaesth2010105Suppl 1i16i2321148651

- CallaghanLCWalkerJDAn aid to drug dosing safety in obese children: development of a new nomogram and comparison with existing methods for estimation of ideal body weight and lean body massAnaesthesia20157017618225289986

- MartinezDWilsonSChildren sedated for dental care: a pilot study of the 24-hour postsedation periodPediatr Dent20062826026416805359

- DosaniFZFlaitzCMWhitmireHCJrVanceBJHillJRPostdischarge events occurring after pediatric sedation for dentistryPediatr Dent20143641141625303509

- CoteCJDischarge criteria for children sedated by nonanesthesiologists: is “safe” really safe enough?Anesthesiology200410020720914739788

- MalviyaSVoepel-LewisTLudomirskyAMarshallJTaitARCan we improve the assessment of discharge readiness?: a comparative study of observational and objective measures of depth of sedation in childrenAnesthesiology200410021822414739792

- TobinCDClarkCAMcEvoyMDAn approach to moderate sedation simulation trainingSimul Healthc2013811412323299051

- TanGMA medical crisis management simulation activity for pediatric dental residents and assistantsJ Dent Educ20117578279021642524

- ShavitIKeidanIHoffmannYEnhancing patient safety during pediatric sedation: the impact of simulation-based training of non-anesthesiologistsArch Pediatr Adolesc Med200716174074317679654

- StratmannGReview article: Neurotoxicity of anesthetic drugs in the developing brainAnesth Analg20111131170117921965351

- SunLEarly childhood general anaesthesia exposure and neurocognitive developmentBr J Anaesth2010105Suppl 1i61i6821148656

- LoepkeAWSorianoSGAn assessment of the effects of general anesthetics on developing brain structure and neurocognitive functionAnesth Analg20081061681170718499597

- Jevtovic-TodorovicVHartmanREIzumiYEarly exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficitsJ Neurosci20032387688212574416

- SlikkerWJrZouXHotchkissCEKetamine-induced neuronal cell death in the perinatal rhesus monkeyToxicol Sci20079814515817426105

- CreeleyCDikranianKDissenGMartinLOlneyJBrambrinkAPropofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brainBr J Anaesth2013110Suppl 1i29i3823722059

- BrambrinkAMEversASAvidanMSIsoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brainAnesthesiology201011283484120234312

- SunLSLiGDimaggioCAnesthesia and neurodevelopment in children: time for an answer?Anesthesiology200810975776118946281

- DiMaggioCSunLSKakavouliAByrneMWLiGA retrospective cohort study of the association of anesthesia and hernia repair surgery with behavioral and developmental disorders in young childrenJ Neurosurg Anesthesiol20092128629119955889

- DiMaggioCSunLSLiGEarly childhood exposure to anesthesia and risk of developmental and behavioral disorders in a sibling birth cohortAnesth Analg20111131143115121415431

- FlickRPKatusicSKColliganRCCognitive and behavioral outcomes after early exposure to anesthesia and surgeryPediatrics2011128e1053e106121969289

- SprungJFlickRPKatusicSKAttention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder after early exposure to procedures requiring general anesthesiaMayo Clin Proc20128712012922305025

- Jevtovic-TodorovicVPediatric anesthesia neurotoxicity: an overview of the 2011 SmartTots panelAnesth Analg201111396596822021791

- Lourenco-MatharuLAshleyPFFurnessSSedation of children undergoing dental treatmentCochrane Database Syst Rev20123CD00387722419289

- LocharyMEWilsonSGriffenALCouryDLTemperament as a predictor of behavior for conscious sedation in dentistryPediatr Dent1993153483528302673

- FranklSShiereFFogelsHShould the parent remain with the child in the dental operatory?J Dent Child196229150163

- IsikBBayginOKapciEGBodurHThe effects of temperament and behaviour problems on sedation failure in anxious children after midazolam premedicationEur J Anaesthesiol20102733634019923993

- WanKJingQZhaoJZEvaluation of oral midazolam as conscious sedation for pediatric patients in oral restorationChin Med Sci J20062116316617086737

- VargasKGNathanJEQianFKupietzkyAUse of restraint and management style as parameters for defining sedation success: a survey of pediatric dentistsPediatr Dent20072922022717688019

- RadisFGWilsonSGriffenALCouryDLTemperament as a predictor of behavior during initial dental examination in childrenPediatr Dent1994161211278015953

- RothbartMKAhadiSAEvansDETemperament and personality: origins and outcomesJ Pers Soc Psychol20007812213510653510

- KainZNCaldwell-AndrewsAAMaranetsINelsonWMayesLCPredicting which child-parent pair will benefit from parental presence duringAnesth Analg2006102818416368808

- JensenBStjernqvistKTemperament and acceptance of dental treatment under sedation in preschool childrenActa Odontol Scand20026023123612222648

- QuinonezRSantosRGBoyarRCrossHTemperament and trait anxiety as predictors of child behavior prior to general anesthesia for dental surgeryPediatr Dent1997194274319348611

- Voepel-LewisTMalviyaSProchaskaGTaitARSedation failures in children undergoing MRI and CT: is temperament a factor?Paediatr Anaesth20001031932310792749

- SalmonKPereiraJKPredicting children’s response to an invasive medical investigation: the Influence of effortful control and parent behaviorJ Pediatr Psychol20022722723311909930

- McMurtryCMChambersCTMcGrathPJAspEWhen “don’t worry” communicates fear: Children’s perceptions of parental reassurance and distraction during a painful medical procedurePain2010150525820227831

- McMurtryCMMcGrathPJAspEChambersCTParental reassurance and pediatric procedural pain: a linguistic descriptionJ Pain200789510116949882

- ChambersCTTaddioAUmanLSMcMurtryCMPsychological interventions for reducing pain and distress during routine childhood immunizations: a systematic reviewClin Ther200931Suppl 2S77S10319781437

- BlountRLDevineKAChengPSSimonsLEHayutinLThe impact of adult behaviors and vocalizations on infant distress during immunizationsJ Pediatr Psychol2008331163117418375966

- BlountRLLandolf-FritscheBPowersSWSturgesJWDifferences between high and low coping children and between parent and staff behaviors during painful medical proceduresJ Pediatr Psychol1991167958091798015

- SinhaMChristopherNCFennRReevesLEvaluation of nonpharmacologic methods of pain and anxiety management for laceration repair in the pediatric emergency departmentPediatrics20061171162116816585311

- KazakAEPenatiBBrophyPHimelsteinBPharmacologic and psychologic interventions for procedural painPediatrics199810259669651414

- WilsonSNathanJEA survey study of sedation training in advanced pediatric dentistry programs: thoughts of program directors and studentsPediatr Dent20113335336021903005

- AdairSWallerJSchaferTRockmanRA survey of members of the american academyof pediatric dentistry on their use of behavior management techniquesPediatr Dent2004215916615132279

- EatonJJMcTigueDJFieldsHWJrBeckMAttitudes of contemporary parents toward behavior management techniques used inPediatr Dent20052710711315926287

- OlabiNFJonesJESaxenMAThe use of office-based sedation and general anesthesia by board certifiedAnesth Prog201259121722428969