Abstract

The elderly population is projected to make up 20% of the total United States population by the year 2030. In addition, epidemiological data suggests increasing prevalence of chronic pain and frailty with advancing age. Pain, being a subjective symptom, is challenging to manage effectively. This is more so in elderly populations with age-specific physiological changes that affect drug action and metabolism. Elderly patients are also more likely to have multiple chronic health pathologies, declining function, and frailty. The barriers present for patients, providers, and health systems also negatively impact efficient and effective pain control. These factors result in disproportionate utilization of health resources by the older population group. The scientific literature is lagging behind in age-specific studies for the elderly population. As a result, there is a lack of age-specific standardized management guidelines for various health problems, including chronic pain. Increasing efforts are now being directed to studies on pain control in the elderly. However, pain management remains inconsistent and suboptimal. This article is an attempt to suggest an informed, comprehensive guide to achieve effective pain control in the presence of these limitations.

Keywords:

Introduction

Advancements in the field of medicine over the last century have resulted in a significant increase in mean survival ageCitation1 and have changed the age distribution curve by adding older adults in the canvas of global population. While investigators must continue finding solutions to medical problems of younger populations, the increasingly aging population brings a different set of puzzles to medicine. We are testing the limits of the health care system with additional physical, social, and economical stress.

Epidemiology of old age

Aging is a normal physiological process characterized by a dynamic, irreversible decline in physiological function.Citation2 Old age (or the older adult) is defined as the age of 65 or older, and the last century had seen escalation in the aging population. This older age population has risen from 4% of the total population in 1900 to 13% in 2010. The trend suggests that the older age population will expand to reach 20%–21% of total population by the year 2030.Citation3 Continuous advancements in medicine, and improved hygiene and nutrition are tempering some of the rise of chronic disability in the elderly ie, 81% older adults identified themselves as nondisabled in 2005 in comparison with 73% in 1982.Citation4

Frailty

Altered physiology and increases in degenerative disease prevalence have influence on the health status of older adults. In one estimate 30%–50% of adults 65 years and older have two or more health problems affecting their life. For those 85 years and over, this statistic rises to 50%–75%.

The interaction of various medical pathologies with age-related body changes results in a physiologic change characterized by decreased ability to respond to stressors. It causes vulnerability to adverse health outcomes, such as functional impairment, falls, fractures, social isolation, hospitalization, etc. This vulnerability is defined as frailty.Citation5 Frailty is diagnosed upon presence of three out of these five factors: (a) weight loss, (b) extreme fatigue, (c) weakness in hand grip, (d) slow walking speed, and (e) low physical activity in older adults.Citation5 Altered cognition, depression, and loss of muscle mass is very common in a frail patient. Pain remains the most common complaint in this group.

Geriatric pain

Along with increasing chronic degenerative changes and multiple medical comorbidities, the prevalence of pain also increases with advancing age. It ranges from 50%–75% and remains under-diagnosed and undertreated.Citation6 Poorly controlled pain, in turn, causes impaired activities of daily living (ADLs), mood disturbances, decreased ambulation, and cognitive alteration. Collectively, these comorbidities lead to other medical morbidities, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, fractures, and poor quality of life.Citation7 Thus, it is of utmost priority to diagnose and manage pain early and effectively.

Pain cure is still an elusive target. The lack of optimal guidelines and inconsistent management make pain even more difficult to manage. Thus, the International Association of Study for Pain (IASP) accepted the declaration “Pain management – a fundamental human right” at Montreal in 2010.Citation8

Pain is an unpleasant, subjective, multifaceted, biopsycho-social experience.Citation9 It encompasses sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational, and cognitive-interpretive dimensions. Each of these components is influenced by physical, psychological, social, and spiritual factors.Citation10 To achieve effective pain control, all of these factors should be addressed.

Challenges in geriatric pain management

There are several factors that make delivery of effective pain management in geriatric population a challenging task. In order to provide effective pain management, we should understand the pathophysiology of pain and the barriers to delivery of appropriate pain care.

Pain process

The pain processCitation11 is comprised of four stages:

(1) Nociception – stimulation of the peripheral pain receptors;

(2) Pain Transmission – travelling of pain signals through C- and A-delta fibers from the periphery to the dorsal horn and ascending in the spinal tracts to the central level; (3) Pain Modulation – modulation of pain signals along the neuraxial pain pathway; and (4) Pain Perception – projection of the pain signal onto the somatosensory cortex.

There are various receptors and neurotransmitters along this pathway that help in translating this action potential from the nociceptors at the periphery into pain perception. Alterations at these stages are the targets for pain management.

Physiologic alterations in older adults

With advancing age, multiple physiological changes occur in the body, altering the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of drugs. This in turn complicates pain management. Changes that occur with aging are summarized in .Citation12,Citation13

Table 1 Physiologic changes with aging and its effects

Barriers in geriatric pain management

Beside the physiological and pathological changes, there are several other factors that hinder optimal pain care delivery.Citation14,Citation15 The shareholders invested in the goal of pain relief also bring their individual prejudices and limitations:

Patient themselves through

Misconceptions (increasing disease, pain as part of aging, nontreatable, medicines should be a last resort),

Fear (of addiction, masking disease progression, being labeled as a weak or bad patient, adverse effects from drugs, loss of independence),

Personality (noncompliance, not wanting to be “a complainer,” denial, negative attitude towards younger practitioners),

Personal (cultural and religious beliefs, language, monetary status, comfort with health care setting, ambulatory status, social support),

Comorbidities (depression, dementia, altered cognition, etc);

Medical professionals through

Lack of knowledge/training (for pain diagnosis, assessment, nonpharmacologic modalities, medication’s side effects and dependence or addiction) resulting in inability to diagnose early, manage effectively, interpret symptoms and side effects, and delay in referral,

Lack of standardized guidelines and protocols for pain management,

Personal biases (towards fear of opioid dependence, addiction, opioid toxicity, legal scrutiny, patient satisfaction),

Time constraints;

Health system through

Accessibility (distance, transportation, insurance coverage, economics, social support, etc),

Facility and health care deficiencies (clear guidelines and protocols, trained professionals, insufficient supportive and ancillary staff, insufficient resources, excessive documentation, fear of legal scrutiny);

Medications/interventions through

Insurance coverage,

Geographic availability,

Medicine (availability, poly-pharmacy, complex dosage regimen, adverse effects, generic vs brand name medications, packaging),

Off-label usage of medications or interventions.

Adverse effects and compliance in elders

An undesired and potentially harmful response from medications is more prevalent in the older adult population. In several studies, the incidence of these adverse reactions ranges from 6% to 30%, and the majority of them are preventable.Citation16

Poly-pharmacy, multiple prescribers, inappropriate use, suboptimal monitoring, and patient compliance are risk factors for adverse events. This is in addition to variances seen secondary to age-related pharmacodynamic and pharma-cokinetic changes of drug metabolism.Citation17

Adverse reactions should not be confused with therapeutic failure, which is described as “given medication but unable to achieve goal of therapy.” A combination of any of the following factors may be responsible for therapeutic failure: poor adherence to medicine, inadequate dosing, drug interactions, and unaffordable cost of medications.Citation18

In the presence of multiple health problems, the elderly population is often at risk for polypharmacy.Citation19 Prior to instituting a new medication, a clear goal, end point, rate of taper and duration, appropriate monitoring, possible side effects, and drugs interactions should be considered to prevent these adverse events. Ongoing efforts are directed at the development of screening tools and lists of high-risk medications to help health care providers choose safe and effective medications for older adults.

A list of medications that pose potential risks outweighing potential benefits for the older population was suggested in 1991, called the “Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.”Citation20 The list was recently updated and modified into three broad categories of high-risk medications for elders (a) in general, (b) in certain specific diseases, or (c) to be used with caution. Concomitant use of the Beers criteria and the “screening tool for older persons prescriptions (STOPP)/screening tool to alert to right treatment (START)” criteriaCitation21 helps health care providers to deliver safe and effective medicinal management.

Management of geriatric pain

“Access to pain management is a fundamental right,”Citation8 and accurate assessment and delivery of effective treatment in timely fashion are critical for better outcomes and patient satisfaction. Understanding the complexities associated with pain management should further challenge medical practitioners. They must put in diligent effort to provide effective pain control through optimal use of knowledge and tools.

Pain assessment

Pain assessment is the key to optimal pain control and determination of its mechanism in elderly populations.

Patient’s self-reporting is the most reliable source in pain assessment.Citation22 Comprehensive pain assessment is an ongoing process in elderly patients, and information may be gained by comparing repeated interactions with health care workers.

A medical history inclusive of pain symptoms detailing location, duration, character, radiation, temporal relationships, and associated neural symptoms helps to narrow down the differential diagnosis. History of medication use and effects is also an essential part of the assessment.

This is further aided by a physical examination, with focus on the patient’s complaints. The patient’s cognitive capacity may be diminished by other comorbidities. Thus, a thorough physical examination and history is essential. Relevant diagnostic tests further compliment the clinical assessment.

Although pain is a subjective symptom, its accurate measurement helps to compare and improve the outcomes of management modalities. Choices of pain measurement tools are dependent upon the patient’s cognitive, visual, auditory, and communicative status. Pain can be rated using: (a) unidimensional scales – these include numeric pain rating scales and pictorial pain rating scales (ie, faces pain scale, colored visual analogue scale, pain thermometer, etc) and are commonly used to rate the intensity of pain; or (b) multidimensional verbal descriptor scales, such as the McGill Pain QuestionnaireCitation23 (describes sensory and emotional effect of pain), the Multidimensional Pain Inventory, etc.Citation24

Pain assessment is not complete without evaluating the impact of the pain on the patient. Pain affects the patient’s psychological and functional status and its impacts may also extend to affect cultural, spiritual and social function of the family and community. It is critical to understand these impacts to provide multidisciplinary pain management. Patient’s mood, coping skills, ability to perform ADLs, use of aids, social and family interactions, etc must be evaluated before formulating the management plan.

Pain assessment is especially challenging in patients with cognitive impairment and dementia, placing this group at risk of under diagnosis and undertreatment.Citation25 When self-report is unavailable, as in the cognitively impaired person, observation of the patient’s behavior pattern will be the primary assessment tool.

Attempts have been made to develop common instruments or guidelines for assessing pain in communicatively and cognitively impaired patients. A hierarchical Pain Assessment AlgorithmCitation26 was proposed that can be utilized for patients who are self-reporting as well as for cognitively impaired patients. It consists of (a) a self-report from patient (or reason for not doing it); (b) behavioral assessment tools for observation of pain behaviors during clinical assessment; (c) an assessment report by the patient’s caregivers; and (d) a listing of analgesic trials and nonpharmacologic interventions and their outcomes.

Management of pain

Managing pain is a challenging task to begin with and it is especially difficult in the elderly population, secondary challenges in their pain assessment. With the lack of age- specific scientific evidence, it is often common to extrapolate the data from young adult studies for clinical decision-making in elders. There is an increased risk of medicine-associated adverse events from poly-pharmacy, lack of age-appropriate treatment guidelines and protocols, lack of age-appropriate drug safety data, multiple comorbidities, and age-related physiological changes. On the other end, aging is also a very individualized process, and age-related changes are extremely varied among individuals.

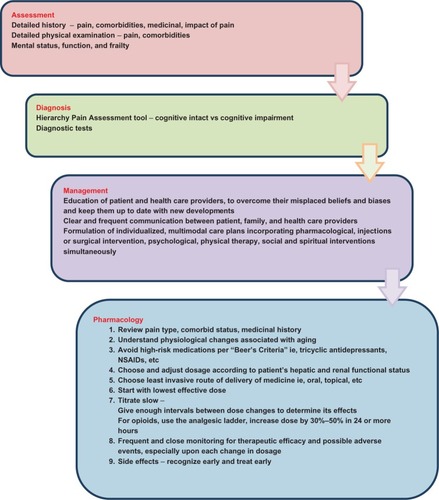

It is important to keep all these challenges, diagnoses, resources, and patient expectations in perspective, to formulate comprehensive multidisciplinary management strategies (). Pain is a multifaceted problem and is best addressed through an individualized approach. The goal should be not only to improve pain control, but also, to improve function and alter pain behaviors.

Figure 1 Management of pain in frail older adults.

Education

Educating both the patients and their health care providers can overcome the prominent barriers to the implementation and delivery of effective pain management.

Nonpharmacological modalities

Nonpharmacological modalitiesCitation27 is essential component for comprehensive multimodal management strategies as it helps patient in coping better with pain and suffering along with improvement in daily functions. Thus these modalities including physical therapy, psychobehavioral therapies,Citation28 pastoral and social work consultation should not be overlooked.

In the frail elderly, it is even more important to improve function, as one of the key modalities in the prevention and management of frailty. Adequate analgesia enables the patient to participate fully and progress in a tailored exercise program, preferably one provided by a physical therapy specialist.

Identification of patients who are at high-risk for fall and fractures is essential. Ergonomic adjustment in patient’s lifestyle can be made to prevent falls or bad outcome from falls. Examples of adjustments include clearing obstacles from passages, softer padding along the passages, and use of walking aid.

A nutritional consultation could be very beneficial for better nutrition, to prevent loss of muscle mass, osteoporosis, and better control of chronic conditions.

Pharmacological modalities

The multidimensional character of pain makes it more difficult for researchers to develop clear, standard protocols for pain management. Geriatric pain thus can be best managed using individualistic and mechanistic treatment strategies.

Pain is classified into broad categories as: nociceptive, neuropathic, psychosocial, visceral, and mixed. Analgesics such as opioids, acetaminophen, and nonsteroidal antiinfammatory drugs are known to be more effective for nociceptive pain. Meanwhile, adjuvants medications, including antiepileptics and antidepressants, are more helpful in neuropathic pain. One should determine the particular type of pain prior to prescribing first-line medications.

Several of these pharmacological agents have multiple delivery routes ie, oral, intravascular, sublingual, mucosal, rectal, transdermal, and intramuscular. Selection of the least invasive route of drug delivery should be the priority in elderly patients.

Upon selection of the medication, this should be started in the lowest effective dose, followed by a gradual and slow titration of dosage.Citation29 There should be adequate intervals between the escalations of medication during titration, to prevent overdosage and side effects from accumulative doses. Although these intervals are not clearly defined in the literature, titration schedules should consider the expected half-life of the medication; in general it takes five times the elimination half-life to reach steady state.Citation30 Titration may also be influenced by a patient’s response to medication use. All along this therapeutic trial, the patient should receive medications around the clock, be closely monitored for therapeutic effect, and report any adverse effect or intolerability. Since mixed pain can often occur, the addition of medications with different mechanisms should not be delayed. Providers should be very careful about drug–drug or drug–disease interactions.

The WHO three-step “analgesic ladder”Citation31 was initially recommended for the management of cancer pain, with emphasis on oral opioids as per the intensity of pain. In time, its use has expanded for managing noncancer pain, including pain in the geriatric population. The goal remains the slow escalation of analgesic dosing to achieve the desired therapeutic goal. Adjuvant medications should be used at the same time, to achieve better analgesia and reduce the opioid consumption. Use of the analgesic ladder has been validated through various studies and achieves the goal of pain relief in 70% of cases,Citation31 but its use is limited to communicative patients who can take oral medications.

Attention should be given to the patient’s physiological, cognitive, and comorbid status. Avoid usage of strong opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and tricyclic antidepressants in the elderly patient.Citation29

Pain medications can be classified according to three broad categories: nonopioid analgesics, opioid analgesics, and adjuvant medications.

Nonopioid analgesics

Acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and steroids are the most commonly used nonopioid analgesics. Acetaminophen is a centrally acting analgesic without anti-infammatory properties. It is metabolized by liver and excreted through the renal system. It is used as an analgesic and also as coanalgesic, meaning it potentiates the effect of opioid analgesics and provides opioid sparing. Acetaminophen is an initial analgesic used for mild pain and for ongoing persistent pain. Caution should be exercised in liver or renal impairment, when doses should be adjusted. Dose escalation is limited, secondary to a ceiling of its effect on analgesia. Dosages should be limited to 2000 mg per day in the elderly.

Chronic usage of NSAIDS should be avoided in the elderly population as these carry a high risk for gastrointestinal toxic effects, and renal and cardiac dysfunction. Shortterm use is suggested, upon cautious assessment of patient comorbidities and with close monitoring for gastrointestinal and renal adverse effects as well as for drug to drug interactions. Concomitant use of a gastro-protective agent (ie, proton pump inhibitor) is recommended with NSAIDs use.Citation29 Topical NSAIDs may be a safe alternate, secondary to their reduced systemic absorption.Citation32

Opioid analgesics

Opioid analgesics are commonly used for moderate to severe pain and pain associated with frailty. They provide analgesia through action on opioid receptors that are present both peripherally as well as in the central nervous system. The WHO analgesic ladderCitation31 guides in the selection and dosing of opioids for moderate pain and severe pain; thus, they are clinically divided in to mild and strong opioids. Hydrocodone, tramadol, and oxycodone are considered mild opioids and can be used for moderate pain that is not controlled by use of nonopioid analgesics. Upon failure to achieve appropriate analgesia with mild opioids, stronger opioids, such as morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, and methadone, should be used. Most of the strong opioids are available in fast-acting and long-acting formulation. In the case of fast-acting opioids, the formulation half-life is usually 2–6 hours, based upon metabolism of the drug. The long-acting formulations allow 8–12 hours of analgesia through sustained-release drug delivery systems ie, matrix-based slow-release MS Contin® or reservoir-based fentanyl patches. The exception is methadone, which is limited by its pharmacodynamic profile.Citation33

Patients should be reassessed frequently with every change in dosing, to monitor its efficacy and side effects.Citation29 In order to prevent side effects from progressing to a poor outcome, it is essential that the provider manage preemptively. Depending upon the patient’s health status and severity of pain, a fast-acting opioid formulation should be started at the lowest effective dose and allowed to titrate slowly. Titration of the dose should be done by increasing each dose by 30%–50% of the current total daily doseCitation33 at a minimum interval of every 24 hours until stabilization at the dose of effective analgesia.Citation34 For severe pain, more frequent titration is recommended. It may be appropriate to initiate use of a long-acting opioid formulation after monitoring the usage of a short-acting opioid formulation. The metabolism of hydromorphone, oxycodone, and methadone is directly dependent on liver function, while elimination of morphine depends upon renal function. Thus, fentanyl could be a preferential opioid in liver dysfunction,Citation35 while methadone and fentanyl are the agents of preference for patients with impaired renal function.Citation36 Morphine, hydromorphone, and hydrocodone should be used with caution in hepatic and renal impairment; methadone use is commonly avoided in these situations, secondary to its complex and variable metabolism.Citation35,Citation36

Propoxyphene, meperidine, pentazocine, and high-dose tramadol (>200 mg/day) should be avoided in elderly patients, secondary to the risk that accumulation of their metabolites could lead to undesired side effects.Citation29 Early in a patient’s management, long-acting opioid formulations should be avoided, secondary to their altered metabolism, presence of polypharmacy, and increased risk of side effects. For chronic pain management, long-acting formulations may be reasonable choices, while fast-acting formulations are utilized for breakthrough and incidental pain.

Methadone is a complex medication in comparison with the other opioids. Although it may be cost effective, there are unpredictable differences in its drug action and clearance. Classically understood, methadone is characterized by an analgesic half-life of 3–6 hours, while the elimination halflife may range from 20 hours to in excess of 120 hours. This creates real challenges for practitioners when titrating the medication on an outpatient basis. Thus, the use of methadone requires a physician with experience and understanding of the medication, along with the need for frequent monitoring and cautious and slow titration of doses.Citation37

Common opioid-induced side effects are constipation, sedation, nausea, endocrine dysfunction, and altered cognition. These effects should be monitored closely and managed promptly, sometimes even preemptively. In addition to treatment with specific medications, side effects can be also managed with dose alteration, change in the route of administration, or change to other opioid formulation.

Constipation is the most common side effect of opioids and requires prophylaxis in the form of stool softener or laxative. Constipation that occurs should be managed aggressively after excluding bowel obstruction. In this setting, it may also be necessary to use additional medications for the bowel regimen, including lactulose and polyethylene glycol. Refractory cases can be managed with peripheral opioid antagonist ie, methylnaltrexone.Citation38

Constipation is the most common reason for nausea, so its management will be essential for nausea control. There are several other antiemetic targets: (a) chemoreceptor trigger zone blockade, managed through droperidol, prochlorperazine, and serotonin antagonism with ondansetron; (b) improvement of gastric motility using prokinetic agents, such as metoproclamide; and (c) reduction in vestibular sensitivity by using antihistaminic and anticholinergics.

Sedation and altered cognition are usually managed by reducing the dosages of opioids, but occasionally stimulants such as dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate will be necessary to negate the central nervous system depressive effect of opioids. Similarly androgen replacement may be needed in opioid-induced hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.Citation39

Opioid rotation is the practice of changing from a poorly responsive opiate medication to another in hopes of improved analgesia and better tolerability. Although a popular strategy, the practitioner must have a clear understanding of the relative potencies of various opioids for effective opioid rotation. These are described in the Opioid Equianalgesic Conversion Table ().

Table 2 Opioid equianalgesic conversion table

Current guidelines help to ensure patient safety by recommending two key dose adjustments when converting to a new opioid: first, calculate the 24-hour requirement of the previous opioid and reduce the initial dose of new opioid by 25%–50%, using the equianalgesic table. This is done in order to negate an “incomplete cross tolerance” among opioids. Second, in high-risk patients (elderly, renal-impaired, or cognitively impaired), the dose should be further reduced by 15%–30%. These guidelines do not apply for methadone, where the initial reduction of dose should be 75%–90% to incorporate its variable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics; and fentanyl patch doses should not be reduced initially.Citation40

Titration of opioids using 5%–15% increments of the total daily dose can be safe when utilizing an appropriate frequency of administration and providing medication on an “as needed” basis. In time, the patient will achieve the desired level of analgesia, and steady state of opioid with subsequent administration.Citation40

Upon selection of opioids for chronic use, providers should also be mindful of compliance, adherence, dependence, tolerance, and addiction issues. Older adults may have difficulty adhering to the plan of care, but educating them can help to overcome this problem.

Adjuvants

Adjuvants are pharmacological agents that were primarily developed for indications other than analgesia. Several medications belong to this group, including antidepressants, antiepileptics, corticosteroids, local anesthetics, muscle relaxants, etc. They are commonly used in conjunction with other analgesics for persistent and refractory pain, but some adjuvants are drugs of choice for neuropathic pain.

Tricyclic antidepressants cause anticholinergic side effects, cognitive impairment, and cardiac dysfunction; thus, it is recommended to avoid these in the elderly population.Citation29 Antiepileptics (ie, gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, tiagabine, and topiramate) are the effective agents in treatment of the neuropathic component of pain. Titration should be done very slowly as all of these agents can produce mild sedation and cognitive alteration. With the exception of lamotrigine and tiagabine, all antiepileptic dosages should be adjusted on the basis of renal function. Gabapentin, pregabalin, and levetiracetam are better choices for patients with hepatic dysfunction but adequate renal systems.Citation41 Alternatively tiagabine and lamotrigine may be better tolerated by patients with renal impairment.Citation42

Presence of frailty sometimes warrants the use of replacement hormones ie, androgens and/or growth hormones for improvement of muscle mass.

Interventional modalities

All practitioners are fully cognizant of the limitations of medication and other modalities. In certain situations, an interventional approach could be significantly beneficial in pain control. These interventions are targeted to the pain pathways, to either obliterate or modulate pain signals through chemical, electrical, or ablative means.

Analgesia can also be achieved by delivering medications peripherally around the nerves or by continuous delivery of medication neuraxially via an implantable pump. The pain signal can also be affected by neuromodulation, as with use of a spinal cord stimulator for pain relief.

Summary

Pain is an extremely common symptom of aging and its management is a challenging task for any physician, secondary to unique individual physiological states, multiple barriers, and associated comorbidities.

Despite the presence of significant limitations, effective and safe pain management is the patient’s right. Education among health professionals, age-targeted clinical trials, frequent and detailed pain assessment, utilization of multiple modalities concomitantly, and the development of common guidelines can facilitate the effective delivery of pain control.

An exponential increase in the number of older adults in the total population with chronic degenerative pathologies presents a significant burden on the current health care system. More elderly-focused, age-specific, clinical, socioeconomic, and epidemiological studies are needed to promote healthy aging, as well as early, safe, and effective management of health problems, including pain.

In summary we recommend the following steps in pain management for frail older adults ():Citation29

Provide a rational, individualized plan of care

Provide comprehensive pain assessment, as this is essential in developing an individualized management plan

Use physical therapy and occupational therapy to keep older patients active and mobile

Avoid high-risk medication (ie, tricyclic antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, etc), as recommended by the BEERS criteriaCitation20

Avoid polypharmacy, if possible

Use the least invasive drug-delivery route

Use the lowest effective dose by starting at low dose and titrating slowly to the desired level

Allow for adequate time to evaluate the dose response

Adjust doses in patients with renal/hepatic impairment or other comorbidities

Adjust one medication at a time

Use multimodality treatment to get the most effective results with least side effects

Reevaluate after each change in plan, and monitor side effects, drug-drug interactions, and drug efficacy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ShreshthaLBLife Expectancy in the United States. CRS Report for Congress, Updated August 16, 2006WashingtonThe Library of Congress2006 http://aging.senate.gov/crs/aging1.pdfAccessed September 19, 2012

- BalcombeNRSinclairAAgeing: definitions, mechanisms and magnitude of the problemBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol200115683584911866480

- aoa.gov [homepage on internet]. A profile of older Americans 2011 Department of Health and Human Services [updated February 10, 2012] Available from http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2011/4.aspxAccessed September 19, 2012

- MantonKGGuXLLambVLChange in chronic disability from 1982 to 2004/2005 as measured by long-term changes in function and health in the U.S. elderly populationProc Nat Acad Sci U S A2006103481837418379

- FriedLPTangenCMWalstonJCardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research GroupFrailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotypeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2001563M14615611253156

- FerrellBAPain evaluation and management in the nursing homeAnn Intern Med199512396816877574224

- CavalieriTAPain management in the elderlyJ Am Osteopath Assoc2002102948148512361180

- International Pain Summit (IPS) of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP)Declaration of MontrealSeattleIASP2010 Available from http://www.iasp-pain.org/PainSummit/DeclarationOfMontreal.pdfAccessed September 17, 2012

- ScascighiniLSprottHChronic nonmalignant pain: a challenge for patients and cliniciansNat Clin Pract Rheumatol200842748118235536

- MelzackRCaseyKLSensory, motivational, and central control determinants of pain: A new conceptual modelKenshaloDThe Skin SensesSpringfieldCharles C Thomas1968423429

- Farquhar-SmithWPAnatomy, physiology and pharmacology of painAnaesth Intensive Care Med20089137

- McLeanAJLe CouterDGAging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacologyPharmacol Rev200456216318415169926

- TumerNScarpacePJLowenthalDTGeriatric pharmacology: basic and clinical considerationsAnnu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol1992322713021605569

- TopinkováEBaeyensJPMichelJPLangPOEvidence-based strategies for the optimization of pharmacotherapy in older peopleDrugs Aging201229647749422642782

- MiltonJCHill-SmithIJacksonSHPrescribing for older peopleBMJ2008336764460660918340075

- GurwitzJHFieldTSHarroldLRIncidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory settingJAMA200328991107111612622580

- HanlonJTSchmaderKEKoronkowskiMJAdverse drug events in high-risk older outpatientsJ Am Geriatr Soc19974589459489256846

- GrymonpreREMitenkoPASitarDSAokiFYMontgomeryPRDrug-associated hospital admissions in older medical patientsJ Am Geriatr Soc19883612109210983192887

- NobiliAGarattiniSMannucciPMMultiple diseases and polypharmacy in the elderly: challenges for the internist of the third millenniumJ Comorbidity201112844

- American Geriatrics Society2012Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc201260461663122376048

- BarryPJGallagherPRyanCO’MahonyDSTART (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)–an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patientsAge Ageing200736663263817881418

- PrkachinKMSolomonPERossJUnderestimation of pain by healthcare providers: towards a model of the process of inferring pain in othersCan J Nurs Res20073928810617679587

- MelzackRThe McGill Pain Questionnaire: appraisal and current statusTurkDCMelzackRHandbook of Pain AssessmentNew YorkGuilford Press19753552

- HerrKAGarandLAssessment and measurement of pain in older adultsClin Geriatr Med200117345747811459715

- WeinerDKOffice management of chronic pain in the elderlyAm J Med2007120430631517398221

- HerrKCoynePJMcCafferyMManworrenRMerkelSPain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: position statement with clinical practice recommendationsPain Manag Nurs201112423025022117755

- WrightASlukaKANonpharmacological treatments for musculoskeletal painClin J Pain2001171334611289087

- KernsRDOtisJDMarcusKSCognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain in the elderlyClin Geriatr Med200117350352311459718

- American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older PersonsPharmacological management of persistent pain in older personsJ Am Geriatr Soc20095781331134619573219

- DerbySChinJPortenoyRKSystemic opioid therapy for chronic cancer pain: practical guidelines for converting drugs and routes of administrationCNS Drugs1998929910911

- GrondSZechDSchugSALynchJLehmannKAValidation of World Health Organization guidelines for cancer pain relief during the last days and hours of lifeJ Pain Symptom Manage1991674114221940485

- MasonLMooreRAEdwardsJEDerrySMcQuayHJTopical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain: systematic review and meta-analysisBMC Musculoskelet Disord200452815317652

- FinePGMahajanGMcPhersonMLLong-acting opioids and short-acting opioids: appropriate use in chronic pain managementPain Med.200910Suppl 2S79S8819691687

- PortenoyRKLesagePManagement of cancer painLancet199935391651695170010335806

- BosilkovskaMWalderBBessonMDaaliYDesmeulesJAnalgesics in patient with hepatic impairment: pharmacology and clinical implicationsDrugs201272121645166922867045

- DeanMOpioids in renal failure and dialysis patientsJ Pain Symptom Manage200428549750415504625

- CavalieriTAManaging pain in geriatric patientsJ Am Osteopath Assoc2007107(Suppl 4)ES10ES1617986672

- HarrisJDManagement of expected and unexpected opioid-related side effectsClin J Pain200824Suppl 10S8S1318418226

- KatzNMazerNThe impact of opioids on the endocrine systemClin J Pain200925217017519333165

- ChouRFanciulloGJFinePGAmerican Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines PanelClinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer painJ Pain200910211313019187889

- AhmedSNSiddiqiZAAntiepileptic drugs and liver diseaseSeizure200615315616416442314

- IsraniRKKasbekarNHaynesKBernsJSUse of antiepileptic drugs in patients with kidney diseaseSeminars in Dialysis200619540841616970741