Abstract

Malignant gliomas consist of glioblastomas, anaplastic astrocytomas, anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and anaplastic oligoastrocytomas, and some less common tumors such as anaplastic ependymomas and anaplastic gangliogliomas. Malignant gliomas have high morbidity and mortality. Even with optimal treatment, median survival is only 12–15 months for glioblastomas and 2–5 years for anaplastic gliomas. However, recent advances in imaging and quantitative analysis of image data have led to earlier diagnosis of tumors and tumor response to therapy, providing oncologists with a greater time window for therapy management. In addition, improved understanding of tumor biology, genetics, and resistance mechanisms has enhanced surgical techniques, chemotherapy methods, and radiotherapy administration. After proper diagnosis and institution of appropriate therapy, there is now a vital need for quantitative methods that can sensitively detect malignant glioma response to therapy at early follow-up times, when changes in management of nonresponders can have its greatest effect. Currently, response is largely evaluated by measuring magnetic resonance contrast and size change, but this approach does not take into account the key biologic steps that precede tumor size reduction. Molecular imaging is ideally suited to measuring early response by quantifying cellular metabolism, proliferation, and apoptosis, activities altered early in treatment. We expect that successful integration of quantitative imaging biomarker assessment into the early phase of clinical trials could provide a novel approach for testing new therapies, and importantly, for facilitating patient management, sparing patients from weeks or months of toxicity and ineffective treatment. This review will present an overview of epidemiology, molecular pathogenesis and current advances in diagnoses, and management of malignant gliomas.

Epidemiology and classification of brain tumors

The estimated number of new cases (adjusted for age) using the world standard population of primary malignant brain and central nervous system cancer in 2008, was 3.8 per 100,000 in males and 3.1 per 100,000 in females. The incidence rates were higher in more developed countries (males: 5.8 per 100,000; females: 4.4 per 100,000) than in less developed countries (males: 3.2 per 100,000; females: 2.8 per 100,000).Citation1 In the US, the annual incidence of primary malignant gliomas is approximately five cases per 100,000 people.Citation2,Citation3 Every year, about 22,500 new cases of malignant primary brain tumor are diagnosed in adults in the US, out of which 70% are malignant gliomas.Citation2,Citation3 Glioblastomas account for approximately 60% to 70% of malignant gliomas, anaplastic astrocytomas for 10% to 15%, and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and anaplastic oligoastrocytomas for 10%; less common tumors, such as anaplastic ependymomas and anaplastic gangliogliomas, account for the rest.Citation2,Citation3

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies astrocytomas based on histologic type,Citation2,Citation4 with grading based on the most malignant region of the tumors. Tumor grade depends upon the degree of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis, with increased anaplasia corresponding to higher tumor grade. Grades include low-grade, or WHO grade I (pilocytic astrocytoma) and grade II (diffuse astrocytoma); and high-grade, or WHO grade III (anaplastic astrocytoma) and grade IV (glioblastoma multiforme, GBM). Grade III and IV tumors are considered malignant gliomas. The median age at the time of diagnosis is 64 years for glioblastomas and 45 years in the case of anaplastic gliomas.Citation5

Apart from primary brain tumors, brain metastases from common solid tumors that spread to the brain primarily include those of lung, breast, and melanoma. However, a recent increase in the incidence of brain metastases from other cancer types, such as renal, prostate, and colorectal cancers, has been observed.Citation6,Citation7

Molecular pathology

Molecular pathology of primary brain tumors

In the past 2 decades, the application of molecular pathology in diagnosis and classification has transformed the management of malignant gliomas.Citation8 Molecular biomarkers have been able to differentiate oligodendroglial tumors from astrocytomas, resolve controversies regarding classification of mixed oligoastrocytic tumors, and identify clinically significant subgroups of anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma.Citation9,Citation10 Recent clinical pathologic correlations between outcome and molecular biomarkers have also validated predictive markers for oligodendrogliomas and identified subgroups of glioblastoma susceptible to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signal transduction inhibitors.Citation11–Citation13

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer has identified six different types of anaplastic oligodendrogliomas using microarray unsupervised gene expression analysis of the tumor specimens obtained as part of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer trial (EORTC 26951).Citation13 These intrinsic molecular subtypes had prognostic significance for progression-free survival (PFS) independent of the previously recognized prognostic factors, including 1p/19q deletion, isocitrate dehydrogenase gene (IDH1) mutation, and OCitation6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation status. One subgroup, with a 1p/19q deletion and IDH1 mutation, especially benefitted from the addition of chemotherapy to external beam radiation, demonstrating an overall survival (OS) of 12.8 years with adjuvant chemotherapy contrasted with 5.5 years for those patients treated with radiation alone.

It is now recognized that patients with oligodendroglial tumors with 1p/19q deletions have a consistently better prognosis for survival than those with tumors of equivalent grade and similar histologic appearance that lack the deletions.Citation14,Citation15 In two recently reported prospective randomized trials of fractionated external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) with or without alkylator-based chemotherapy for newly diagnosed anaplastic astrocytoma, the presence of 1p deletions was a predictive marker for the cohort of patients in which the addition of chemotherapy led to prolonged OS.Citation11

The identification of mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) isoenzymes 1 and 2 in a high percentage of low grade gliomas and in subsets of anaplastic astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and glioblastoma has further refined the delineation of prognosis. IDH1 is a good prognostic marker for anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma.Citation9,Citation16 For anaplastic astrocytoma, lack of an IDH1 mutation appears to identify a subgroup of histologically indistinguishable tumors with a prognosis similar to glioblastoma.Citation17 The oncogenic mechanism appears to be the production of a metabolite, 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG), which inhibits ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases, leading to aberrant histone and DNA methylation.Citation16

In clinical trials of alkylator-based chemotherapy regimens for glioblastoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, and oligodendroglioma,Citation9,Citation18 the MGMT promoter methylation status has proven to be a prognostic, though not a specific predictive biomarker. Hegi et al demonstrated that promoter methylation silencing of the MGMT gene correlates strongly with long-term survival in patients receiving chemotherapy.Citation19 At the same time, Brandes et al showed that for patients receiving chemoradiation for newly diagnosed GBM, MGMT promoter methylation silencing correlates with increased frequency of vascular permeability of vessels in the radiation treatment field.Citation20 This may produce a transient increase in the volume of contrast taken up by the lesion, known as “pseudoprogression”.Citation20

GBMs that arise de novo appear to be different genetically from those that arise from prior low-grade astrocytomas.Citation9 IDH and p53 mutations are rare in primary GBM. In contrast, primary GBMs are characterized by EGFR amplification and mutation, loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 10q, and inactivation of the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) gene.Citation21 Secondary GBMs are characterized by tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutations and platelet-derived growth factor receptor activation.Citation21 A poor prognosis subgroup of secondary GBM in older adults, in which relapse occurs in the first year after treatment, appears to be characterized by lack of IDH1 mutations, similar to primary GBM’s molecular signature.Citation22

Microarray-based unsupervised genome-wide analysis of gene expression in glioblastomas has identified at least four subgroups differentiable by molecular profile.Citation23 Phillips et al examined 107 grade III and IV astrocytomas, and using a set of 35 signature genes, segregated into three subtypes: proneural, proliferative, and mesenchymal.Citation24 In this study, the proneural subset had a better prognosis than the proliferative and mesenchymal subsets, which had worse prognoses.

The investigators of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) pilot projectCitation25 proposed a four-subgroup classification based on analysis of 202 GBMs. The subtypes include proneural, neural, classical, and mesenchymal. In the context of the cancer genome atlas, Noushmehr et al profiled promoter DNA methylation alterations in 272 glioblastomas (43 low and intermediate grade gliomas and 57 additional primary GBMs).Citation26 They reported a distinct subset of tumors with increased DNA methylation at large number of loci, indicating the existence of a glioma–CpG island methylator phenotype (G–CIMP).Citation26 Within the GBM cohort, the G–CIMP phenotype correlates with IDH1 mutation, younger age, proneural genotype, and a better prognosis.

The EGFR gene is the most frequently amplified gene in primary GBM and is seen in 94% of the TCGA classical type,Citation25 and in the proliferative and mesenchymal subtypes in the Phillips classification.Citation24 A specific in-frame deletion of exons 2–7 is present in 20%–30% of GBM overall and 50%–60% of GBM with EGFR gene amplification.Citation27 The protein product of this truncated mRNA is the EGFRvIII mutant protein. This protein is the target antigen for immunotherapy strategies, including vaccines. Although the small molecule EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors trials for patients with GBM and anaplastic astrocytoma demonstrated low response rates and no benefit in PFS, a small subset of patients had durable responses.Citation28 A specific genotype correlated with response in which EGFRvIII mutation was present in the context of intact AKT pathway function, with wild-type PTEN.Citation29

BRAF (an oncogene located on chromosome 7) encodes a serine threonine kinase involved in cell signaling, and also involved in mitogen-activated protein kinases/extracellular signal regulated kinases pathway activation, and cell growth is most commonly associated with low-grade pediatric gliomas, but is commonly seen in high-grade diffuse gliomas as well. The most common BRAF abnormalities involve gene duplication with fusions leading to a mutant protein with a constitutively active kinase domain.Citation9 Mutation in p53 and BRAF appear to be mutually exclusive.Citation30 The presence of activating BRAF mutations may identify a therapeutic target in the high-grade gliomas in which it is expressed. BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved as treatment for melanoma with BRAFV600E mutation.Citation31

Molecular markers are also useful to predict a response to chemotherapy in three settings: 1p and 19q loss, MGMT methylation, and possibly the EGFR–PI3 kinase pathways in response of glioblastomas to specific EGFR inhibitors.

1p and 19q deletions

Allelic loss of chromosomes 1p and 19q is a powerful predictor of chemotherapeutic response and longer PFS and OS following chemotherapy with either temozolomide or procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (PCV) in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. Those tumors with 1p and 19q loss in the setting of polysomy of chromosomes 1 and 19 have intermediate prognoses. Allelic loss of 1p alone is also predictive of response to temozolomide in patients with grade II oligodendroglial tumors.Citation32 Thus, testing for 1p and 19q status is now widespread and is used to influence therapeutic decisions.

MGMT promoter methylation

In the course of tumor development, the MGMT gene may be silenced by methylation of its promoter, thereby preventing repair of DNA damage and increasing the potential effectiveness of chemotherapy. Several clinical studies have indicated that such promoter methylation is associated with an improved survival in patients receiving adjuvant alkylating agent chemotherapy.Citation33

EGFR-PI3 kinase pathways

Two studies evaluated patients with glioblastomas treated with the EGFR inhibitors, erlotinib or gefitinibCitation34,Citation35 and found that, in contrast to other studies that did not report objective responses,Citation36 patients with recurrent glioblastoma responded to these two agents. Furthermore, the studies showed associations between response and activation of EGFR itself (one report implicating the wild-type receptorCitation34 and the other implicating the vIII mutant EGFRCitation35), as well as between response and whether the PI3 kinase pathway was functionally intact (one report measuring phosphorylated AKT and the other measuring PTEN expression). If responses continue to be documented with these agents, immunohistochemical testing for EGFR and the PI3K pathway may prove useful.

Molecular pathology of brain metastases

The pathophysiology of brain metastasis is complex and distinct from primary brain tumors. It is dependent upon both oncogenic processes and host organ responses. Some of the multiple mechanisms that ultimately determine the development of a brain metastasis include, but are not limited to, the phenotype of the brain-trophic tumor cells, tumor cell survival in the vasculature and extravasation of those cells from the bloodstream and into a host organ, and the structure and function of the blood–brain barrier (BBB).

Since the brain does not contain lymphatics, circulating tumor cells reach the brain parenchyma only via a hematogenous route. Invading metastatic cancer cells interact with all cell types, including endothelium, pericytes, and astrocytes, to breach the BBB and gain access to brain parenchyma.Citation37 Once tumor cells enter the brain parenchyma, a number of factors are released by both the tumor cells and the underlying brain. In co-culture experiments, lung-cancer-derived cells release tumor-associated factors, including macrophage migration inhibitory factor, interleukin-8, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, which stimulate astrocytes. In turn, the activated astrocytes release interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-1β, which induce tumor cell proliferation.Citation38,Citation39

Receptor biomarkers indicating an enhanced potential for the development of central nervous system metastases may be identified in the primary tumor cell and thereby define future therapeutic targets. For example, overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu) is predictive of a three-fold increase in metastases to the lungs, liver, and brain as compared with HER2/neu-negative breast carcinomas.Citation40–Citation42 In lung adenocarcinoma, genetic alterations in homeobox protein Hox-B9 and lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 lead to hyperactivity of the Wnt/T Cell Factor (Wnt/TCF) pathway, which has been implicated in the growth of cancer stem cells and enhanced competence to metastasize to the bone and brain.Citation43,Citation44

Diagnosis

Clinical signs and symptoms

Although the symptoms and signs produced by malignant gliomas will vary with the location of the tumor, a unifying characteristic of the clinical presentation is relentless progression. For tumors that are located in or subjacent to cortical regions with specific functions, the symptoms and signs will relate to the functions of the brain regions affected. Patients may present with progressive motor or sensory disturbances, language dysfunction, visual field abnormalities, or focal seizures. Tumors arising in the brain stem may cause rapidly progressing cranial neuropathies as well as motor and sensory deficits. Neurologic deficits with less localizing features may include headache, confusion, memory loss, and personality changes.

As the size of tumor increases, the edema surrounding the tumor increases, resulting in increased intracranial pressure and subsequent headaches. The headaches associated with increased intracranial pressure are typically worse when the patient is recumbent. When intracranial pressure rises to a critical threshold, changes in blood pressure due to dysfunctional autonomic reflexes may produce a syndrome of position-evoked crescendo headache, visual obscurations, lightheadedness, and exacerbation of focal symptoms. This cluster of symptoms is associated with intracranial pressure waves and is usually associated with papilledema.

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging plays a crucial role in diagnosing and assessing the location, extent, and biologic activity of the tumor before, during, and after treatment. Its role in low-grade tumors lies in the monitoring of possible recurrent disease or anaplastic transformation into high-grade tumors. In high-grade tumors, neuroimaging is much needed for differentiating recurrent tumor from treatment-induced changes such as radiation necrosis.

Gliomas are often characterized by diffuse infiltration of white matter tracts,Citation45 and stereotactic biopsy studies have demonstrated that these regions appear normal on conventional contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).Citation46 Since complete resection of infiltrative high-grade neoplasms is not an option,Citation47 the development of improved posttreatment imaging to detect residual tumor is pivotal in clinical outcome.

MRI serves as the current gold standard in tumor treatment response monitoring; however, prognostic information cannot be obtained until weeks after the initiation of treatment.Citation48 Determination of recurrence versus treatment effects on CT or MRI cannot be accurately evaluated.Citation49–Citation51 Functional imaging can distinguish cerebral necrosis from viable brain tumor, and determine viability grade.Citation52–Citation54

The realization that the MacDonald criteriaCitation1 for response assessment in clinical trials of treatments for high-grade gliomas failed to account for nonenhancing progression has led to the development of a new paradigm, the Response Assessment for Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria.Citation55 Differentiating tumor response related to cytotoxicity from physiologic modifications of BBB function is a major focus of translational imaging research. MRI techniques that interrogate the vascular density and permeability of tumor vasculature as well as positron emission tomography (PET) techniquesCitation56 are being evaluated as imaging biomarkers of tumor response in treatment trials of anti-angiogenic therapy.Citation57

CT

Most of the time, CT is the first imaging modality for evaluating symptoms of gliomas. Contrast-enhanced CT scans can delineate disruptions in the BBB, but CT sensitivity is much lower than that of MRI. The attenuation difference can offer limited information on tumor biology. For instance, slightly increased tissue density during tumor monitoring may indicate increase in tissue cellularity, or tumor growth. On the other hand, decreased attenuation in the treated region indicates low tumor cellularity or edema. However, the exact delineation of tumor borders or the extent of treatment-related changes is not feasible using this modality.

MRI

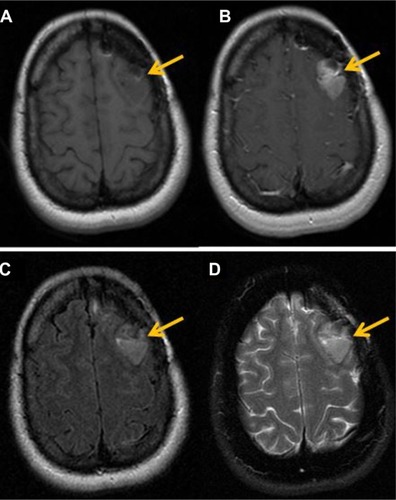

The clinical gold standard for brain tumor imaging, MRI, utilizes T1- and T2-weighted sequences, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences, and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging for tumor monitoring. Glioblastoma is classically hypointense to isointense, with a ring-pattern of enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images, and is hyperintense on both T2-weighted and FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) images ().Citation58,Citation59 It can be focal, multifocal, or diffuse (gliomatosis cerebri).

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance findings in GBM.

Notes: (A) T1 pre-contrast images exhibit a hypointense lesion in the left frontal lobe region (arrow). (B) Axial T1 post-contrast images, after injection of 20 cc of intravenous MultiHance®, demonstrate a focus of enhancement in left frontal lobe. (C) Axial T2 FLAIR images show increase in FLAIR signal in the left frontal lobe, which demonstrates enhancement. (D) T2 FSE images also demonstrate increase in signal in the region of the left frontal lobe.

Abbreviations: FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; FSE, fast spin-echo; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme.

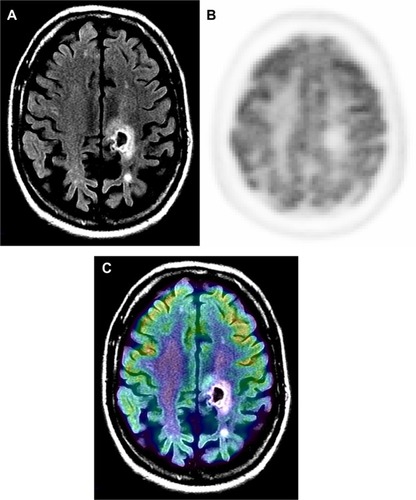

MRI provides excellent anatomic detail; however, it cannot reliably differentiate between radiation necrosis and recurrence posttreatment ().Citation60,Citation61 This is of critical importance in monitoring tumor response to chemoradiation and stereotactic radiosurgery, both of which are associated with high prevalence of post-therapy necrosis.

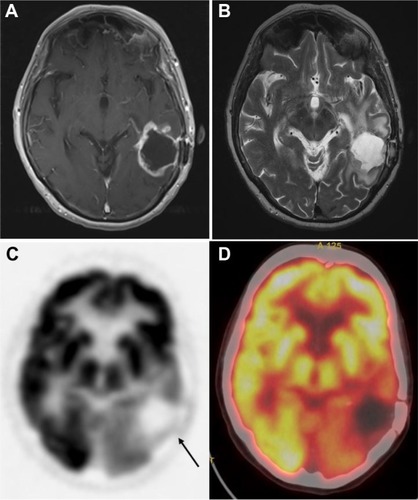

Figure 2 Radiation necrosis versus viable tumor on MRI.

Notes: Sixty-nine-year-old male with glioblastoma multiforme, status post-chemotherapy presented with dizziness. Contrast MRI and 18F-FDG PET were performed to evaluate for progression. Post-contrast T1 MR (A) is suggestive of rim enhancement of tumor (arrow). 18F-FDG PET (B) and PET-MR fusion (C) images show an area of relatively decreased activity corresponding to the area of rim enhancement. PET findings were diagnostic for nonviable tissue. In this case, MR was unable to differentiate between radiation changes and viable tumor.

Abbreviations: FDG, 2-fluorodeoxyglucose; MR, magnetic resonance; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography.

Although BBB destruction with subsequent leakage of contrast medium is commonly seen in most high-grade tumors, such as glioblastomas, it is not a reliable distinguishing feature of tumor grade.Citation62 In fact, approximately one-third of nonenhancing gliomas are malignant.Citation63 Moreover, glioblastoma may initially present as a nonenhancing lesion, especially in older patients. In addition, contrast enhancement cannot always be used to assess response since therapy may result in BBB disruption without a corresponding change in tumor status.Citation64,Citation65

After therapy, physiologic MRI can provide insights into changes in tumor environment related to metabolism (magnetic resonance spectroscopy [MRS]), perfusion (perfusion-weighted imaging), and microstructure (diffusion-weighted imaging [DWI]). Indeed, apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) measurements,Citation66–Citation68 DWI values,Citation69 and fluid-attenuation inversion recovery imagesCitation70 correlate with the probability of response to therapy.

1H MRS

The magnetic resonance spectrum from 1H MRS contains peaks representative of different (hydrogen-containing) metabolites. The relative concentration of each metabolite is determined from the area under the corresponding peak. Whereas single-voxel spectroscopy yields a single spectrum from a defined tissue area, two- and three-dimensional chemical shift imaging depict one or more tissue slices with several voxels in each slice to better account for tissue inhomogeneities.

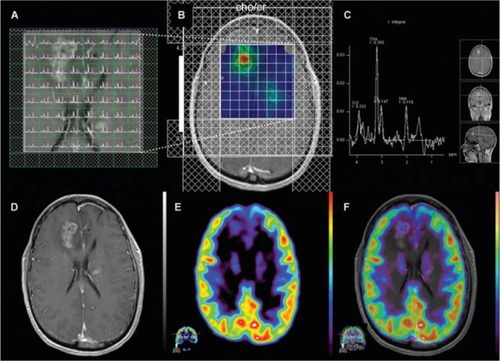

In the case of tumor monitoring, tumor metabolite data are compared to those of the contralateral healthy side. The most commonly examined metabolites include lactate as a product of anaerobic glycolysis,Citation71 N-acetylaspartate as a sign of neuronal viability and density,Citation72,Citation73 choline as an indicator of high membrane turnover and thus cell proliferation,Citation74,Citation75 and creatine as a signature of cell energy expenditure used for an internal reference value.Citation76 Increasing choline/creatine ratios and lactate concentrations,Citation75 and decreasing N-acetylaspartateCitation77 correlate with tumor progression, and can also be seen in tumor recurrence (). Whereas elevated creatine values (normalized to normal brain) correlate with a shorter time-to-progression in WHO grade II and III astrocytomas,Citation78,Citation79 no correlation was identified between tumor grading and choline/creatine ratio.Citation80

Figure 3 Magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Notes: Anaplastic astrocytoma, WHO grade III. Multiple-voxel spectra coregistered with post-contrast T1-weighted MRI (A). Map of Cho/Cr demonstrates a focus of signal intensity in the right frontal lobe (B). MRSI signal intensity is presented on a rainbow color scale where blue-green is normal background and bright red corresponds to greatly elevated signal intensity. Spectral analysis of the voxel demonstrating maximal Cho/Cr ratio (C). T1-weighted MRI (post-contrast) demonstrating enhancing lesion in the right frontal lobe (D). 18F-FDG PET scan shows a focus of increased tracer activity greater than white matter in the right frontal lobe (E). 18F-FDG PET image coregistered with post-contrast T1-weighted MRI (F). Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Imani F, Boada FE, Lieberman FS, Davis DK, Deeb EL, Mountz JM. Comparison of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy with fluorine-18 2-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography for assessment of brain tumor progression. J Neuroimaging. 2012;22(2):184–190.Citation80 Copyright © 2010 by the American Society of Neuroimaging.

Abbreviations: Cho/Cr, choline/creatine; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; WHO, World Health Organization; FDG, 2-fluorodeoxyglucose; PET, positron emission tomography.

A study by Imani et al compared the accuracy of high-field proton MRS (1H MRS) and 18F 2-fluorodeoxyglucose PET (18F-FDG PET) for identification of viable tumor recurrence in 12 grade II and III glioma patients and showed that 1H MRS imaging was more accurate in low-grade glioma and 18F-FDG PET provided better accuracy in high-grade gliomas.Citation80 The study also suggested that the combination of 1H MRS data and 18F-FDG PET imaging can enhance detection of glioma progression. While the sensitivity of 18F-FDG PET in detecting glioma progression was very high (100%), its specificity in differentiating post-therapy inflammation from true tumor progression was low (71%), leading to a high false positive rate (29%) in post-radiation therapy patients.

Studies have looked into the significance of IDH mutational status in the diagnosis and classification of gliomas and the identification of an oncometabolite, 2HG, which accumulates in IDH mutant tumors.Citation9,Citation16 Recent investigations using ultrahigh field strength MRI suggest that the presence of IDH mutations in a tumor can be noninvasively detected by spectroscopic measurement of 2HG.Citation81 Recently, investigators in the US and Europe have demonstrated that MRS can differentiate 2HG from neighboring metabolites, such as gamma amino butyric acid, glutamine, and glutamate. Kalinina et alCitation82 analyzed brain tumor specimens to show the feasibility of using MRS to quantitate 2HG for the classification of IDH mutant tumors. Subsequently, Pope et alCitation83 demonstrated detection of 2HG by MRS in glioma patients prior to resection, with analysis of IDH1 status by DNA sequencing, and measurement of concentrations of 2HG and other metabolites by liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy. In tumors with IDH1 mutations, 2HG levels, as measured in vivo using water suppressed proton (1H) MRS, correlate with measured amounts in the resected tumor specimens. Tumors with IDH1 mutations have elevated choline and decreased glutathione levels. Elkhaled et alCitation81 also demonstrated that levels of 2HG correlate with levels of choline, lactate, and glutathione, as well as with histopathologic grade. While it appears that MRS can provide a noninvasive measure of 2HG in human gliomas, further studies are needed to validate the utility of 2HG quantitation and the relevance of other alterations in metabolites as prognostic biomarkers.

DWI-MRI

DWI relies on the microscopic motion of water molecules within tissue. The process is influenced by temperature and tissue architectureCitation84 and is commonly quantified by the ADC. Tumor infiltration alters tissue architecture and thus water diffusion. ADC decreases with an increase in viscosity, cellular density, and reduction of extracellular space. Low values in ADC maps in solid gliomas are associated with higher-grade tumors.Citation85 Complicating the interpretation is coexistent posttreatment edema which may alter ADC values. The recently introduced higher-order diffusion technique, diffusion kurtosis imaging,Citation86 is being studied to characterize microstructural changes, and initial findings appear promising in the differential diagnosis of brain tumors.Citation87

Perfusion-weighted MRI

Perfusion-weighted imaging involves the quantification of cerebral blood volume (CBV) after contrast administration with a dynamic MRI sequence sensitive to T2* effects. A graph of contrast enhancement is generated to calculate the area under the signal curve as an estimate of relative CBV (rCBV). High-grade gliomas, in particular, are associated with disruption of the BBB, which causes more contrast extravasation and consequent adjustments to rCBV calculations with sophisticated mathematical models.Citation88 Preloading of contrast medium has been applied to minimize the effects of leakage.Citation89,Citation90 Increased angiogenesis in high-grade gliomas is also correlated with higher CBV relative to contralateral normal white matter rCBV and tumor aggressiveness.Citation91–Citation93 Quantitative analysis found a threshold of rCBV =1.75 for determining a high-grade gliomaCitation91 and a higher rCBV ratio of about 2.14 for oligodendrogliomas.Citation94 It has also been shown that an increase in rCBV occurs up to 12 months prior to malignant transformation as assessed by new contrast enhancement.Citation95

PET

Imaging glucose metabolism – 18F-FDG

18F-FDG PET has allowed monitoring of therapeutic response in brain tumors with a greater specificity than CT or MRI. 18F-FDG, a glucose analog, is taken up by high-glucose-using cells, including normal brain and cancer cells. FDG is actively transported across the BBB into the cell and the 18F-FDG-6-phosphate formed when 18F-FDG enters the cell and prevents its further metabolism. As a result, the distribution of 18F-FDG is a good reflection of the distribution of glucose uptake and utilization by cells in the body.

Since most cancer cells, including gliomas, demonstrate a high rate of glycolysis,96 18F-FDG helps in differentiation between tumor and normal brain tissue. It should be noted, however, that the correlation between 18F-FDG uptake and glucose metabolism in tumors may differ from that in normal tissue.Citation97 In untreated tumor, the degree of 18F-FDG uptake has been correlated with tumor grade: high-grade tumors demonstrate increased tracer uptake, and high uptake in a previously categorized low-grade tumor confirms anaplastic transformation of the tumor.Citation98,Citation99 Quantitatively, ratios of 18F-FDG uptake in tumors to that of white matter (>1.5) or gray matter (>0.6) were able to distinguish low-grade (grades I and II) from high-grade tumors (grades III and IV).Citation100 Based on a preliminary finding, delayed imaging at 3–8 hours after injection can further distinguish tumor and normal gray matter due to the faster tracer excretion in normal brain than in tumor.Citation101 However, after therapy the degree of tracer uptake does not necessarily correlate with tumor grade in that high-grade tumors may have uptake similar to or slightly above that of white matter.Citation102

18F-FDG PET also plays a role in differentiating between recurrent or residual tumor and radiation necrosis ( and ). However, due to the 18F-FDG uptake in normal brain, the sensitivity of detecting recurrent or residual tumor is low.Citation103,Citation104 The specificity is also low in the initial few weeks post-therapy due to radiation necrosis. A study showed a sensitivity of 81%–86% and a specificity of 40%–94% for distinguishing between radiation necrosis and tumor.Citation105 It is thus recommended that 18F-FDG PET should not be performed before 6 weeks after the completion of radiation treatment.

Figure 4 Tumor recurrence versus radiation induced changes: images of a 77-year-old male who was originally diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, treated with external beam radiation and adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide.

Notes: Ten-month follow-up MR T1 post-contrast images (A) demonstrate a distinct area of enhancement (arrow) in the left temporoparietal lobe region of prior tumor. T2-weighted MR images (B) demonstrate hyperintense signal in the left parietal lobe extending to the left temporal lobe. This pathologic contrast enhancement is suggestive of an infiltrative mass. FDG PET only (C) and PET-CT fusion images (D) demonstrate a focus of increased FDG activity corresponding to an enhanced area of uptake on post-contrast T1 images. These findings are consistent with tumor recurrence. There is also decreased tracer uptake surrounding these areas consistent with vasogenic edema.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FDG, 2-fluorodeoxyglucose; MR, magnetic resonance; PET, positron emission tomography.

Figure 5 18F-FDG PET for tumor recurrence: 71-year-old male patient with history of glioblastoma multiforme, status post-resection presents for evaluation of recurrence.

Notes: Contrast-enhanced MR T1 images (A) demonstrate a large cavity in the left posterotemporal-parietal junction with an irregular rim of enhancement. T2-weighted MR images (B) demonstrate hyperintensity in the posterotemporal and parietal lobes. These findings are suspicious for tumor recurrence around the periphery of previous location of mass in the left posterior temporoparietal region. (C) 18F-FDG PET only and (D) PET-CT fusion images demonstrate a relatively large area of absent 18F-FDG uptake corresponding to the cavity noted on MRI, with no area of abnormally increased 18F-FDG to suggest the presence of residual or recurrent high-grade viable tumor.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FDG, 2-fluorodeoxyglucose; MR, magnetic resonance; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography.

Recently, new issues have emerged regarding the evaluation of disease response, and also with the identification of patterns such as pseudoprogression, frequently indistinguishable from real disease progression,Citation106 and pseudoresponse. The Macdonald criteria,Citation107 widely used clinically as a guideline for evaluating therapeutic response in high-grade gliomas, uses contrast-enhanced CT and MRI, and defines progression as greater than a 25% increase in size of enhancing tumor. Enhancement of brain tumors, however, primarily reflects a disturbed BBB.

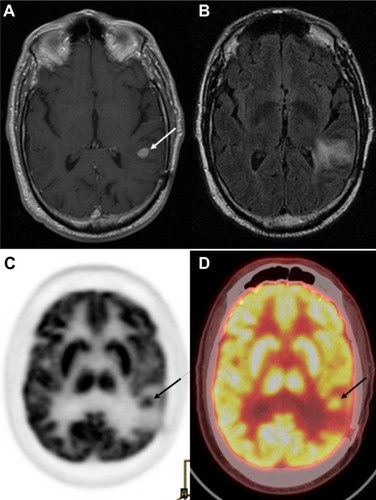

By definition, pseudoprogression of gliomas is a treatment-related reaction of the tumor with an increase in enhancement and/or edema on MRI, suggestive of tumor progression, but without increased tumor activity (). Typically, the absence of true tumor progression is shown by a stabilization or decrease in size of the lesion during further follow-up and without new treatment. Pseudoprogression occurs frequently after combined chemo-irradiation with temozolomide, the current standard of care for glioblastomas.Citation20,Citation65

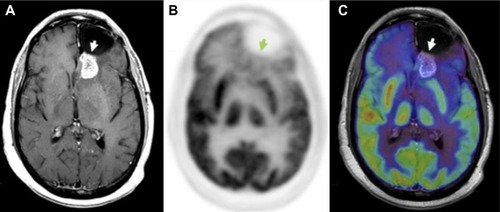

Figure 6 18F-FDG PET diagnosis of pseudoprogression.

Notes: Patient with a history of glioblastoma, status post-resection, now after treatment with total dose of 60 Gy in 2-Gy fractions presents for a follow-up, 1 month after radiation therapy. MRI (A) demonstrates enhancement posterior to the prior resection cavity in the left frontal lobe (arrowhead). However, the patient showed clinical improvement, and therefore an 18F-FDG PET scan was done to assess for tumor progression. On PET (B), no abnormal areas of increased 18F-FDG uptake in the region of MRI contrast enhancement were identified (C), thus additional therapy was deemed not indicated; the patient was monitored on follow-up contrast-enhanced MRI scans, which were negative. Thus, PET scan was helpful in differentiating pseudoprogression from true progression. Adapted with permission from Lippincott Williams and Wilkins/Wolters Kluwer Health: Oborski MJ, Laymon CM, Lieberman FS, Mountz JM. Distinguishing pseudoprogression from progression in high-grade gliomas: a brief review of current clinical practice and demonstration of the potential value of 18F-FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(5):381–384.Citation56 Copyright © 2013. Promotional and commercial use of the material in print, digital or mobile device format is prohibited without the permission from the publisher Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Please contact [email protected] for further information.

Abbreviations: FDG, 2-fluorodeoxyglucose; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography.

In an effort to identify patients likely to exhibit pseudoprogression, some studies have attempted to correlate MGMT promoter methylation status with pseudoprogression.Citation20 Studies have demonstrated that MGMT methylation status is an important biomarker for assessing primary brain tumors, as MGMT status has been shown to correlate with both therapy response and OS in GBM when therapy includes alkylating agents.Citation19,Citation108 However, similar studies of MGMT promoter methylation in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas were unable to find a correlation between MGMT methylation status and either response rate, time-to-progression, or OS, suggesting that MGMT promoter methylation patterns may be dependent on cell type.Citation109

Another phenomenon, pseudoresponse, is the decrease in contrast-enhancement and/or edema of brain tumors on MRI without a true antitumor effect. It occurs after treatment with agents that induce a rapid normalization of abnormally permeable blood vessels or regional cerebral blood flow.Citation110 Recent trials on high-grade gliomas with agents that modify the signaling pathways of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), formerly also known as the vascular permeability factorCitation111,Citation112 (eg, bevacizumab, cediranib), have shown a rapid decrease in contrast enhancement with high response rate and 6-month PFS (PFS-6), but with rather modest effects on OS.Citation111–Citation113

These two opposing phenomena emphasize that enhancement by itself is not a measure of tumor activity, but only reflects a disturbed BBB. A recent case report by our group emphasizes the value of 18F-FDG PET when pseudoprogression is strongly suspected by the referring physician.Citation56 Currently, 18F-FDG PET is not a clinically standard method for evaluating therapeutic response in high-grade gliomas, as it is only used for initial staging and to confirm suspected recurrence observed on gadolinium MRI (Gd-MRI). However, a central advantage of 18F-FDG PET is that it can be used to determine the metabolic state of tumor cells, in contrast to Gd-MRI, which is limited to evaluating changes in size of contrast enhancement. This is an important distinction in comparing 18F-FDG PET and Gd-MRI results, as changes in contrast enhancement are generally a conglomeration of many effects, such as local vascularity, changes in both normal and tumor cell density, necrosis, apoptosis, and BBB breakdown. All of these morphological changes are presumably preceded by changes in tumor metabolism, suggesting that, in many cases, 18F-FDG PET may allow for comparatively faster discrimination of pseudoprogression from true progression and pseudoresponse from true response.

Recent efforts have focused on the coregistration of PET and MRI images, which has increased sensitivity over using either modality alone.Citation114,Citation115 The simultaneous PET–MRI scan, which offers better MRI-based motion correction of PET data, is also being studied in more centers.Citation116,Citation117

Amino acid PET tracers

Amino acid and amino acid analog PET tracers are better suited than 18F-FDG for quantitative monitoring of tumor response due to higher tumor-to-normal-tissue contrast.Citation118–Citation122 The use of amino acids for tumor imaging is based on the observation that amino acid transport is upregulated in malignant transformation.Citation123,Citation124 Response after chemotherapy can be detected by amino acid PET early in the course of treatment,Citation125–Citation127 suggesting that deactivation of amino acid transport is an early sign of response to chemotherapy. Amino acids are transported across the cell via a carrier-mediated mechanism.Citation128 For example, transport of the 18F amino acid analog 3-O-methyl-6-18F-fluoro-L-DOPA via sodium-independent, high-capacity amino acid transport systems has been demonstrated in tumor cell lines.Citation129 In gliomas, increased amino acid uptake is mediated by type L amino acid carriers, which are upregulated in tumor vasculature.Citation124,Citation130 This is in part attributed to the increased metabolic demand of tumor cells. Several amino acid tracers are available, though they are not FDA-approved in the US; eg, O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (FET), 3,4-dihydroxy-6-18F-fluoro-L-phenylalanine, and of 11C methionine (MET).Citation131,Citation132

MET: The best-studied PET amino acid isotope has been l-[methyl-11C] methionine (11C-MET),Citation133 which is able to differentiate tumor recurrence from radiation necrosis.Citation134 However, due to the relatively short 11C half-life of 20 minutes, it requires a nearby cyclotron. The extent of tracer uptake is greater than the degree of contrast enhancement indicative of better delineation of tumor margins.Citation135 In low-grade gliomas, the uptake is increased in the absence of BBB breakdown, which is a significant advantage over CT, conventional MRI, and 18F-FDG PET.Citation136,Citation137 The tracer uptake has been shown to correlate with prognosis and survival in low-grade gliomas.Citation138,Citation139 In high-grade gliomas, 11C-MET uptake is greater than in low-grade tumors,Citation140–Citation142 establishing its potential for use in monitoring anaplastic transformation. In fact, recent findings show that increased 11C-MET uptake during tumor growth parallels an upregulation of angiogenic markers such as VEGF.Citation143 Moreover, the addition of 11C-MET PET changed patient management in half the cases.Citation144

18F-FET (fluoro-3′-deoxy-3′-l-fluorothymidine) is another PET tracer studied for its potential role in the differentiation of radiation necrosis and residual tumor. Indeed, the absence of 18F-FET uptake in a case of radiation necrosis was shown,Citation131 but further systematic studies are necessary to confirm this finding. In contrast to 18F-FDG, 18F-FET uptake was absent from macrophages, a common inflammatory mediator.Citation145 In another study, the ratio of 18F-FET uptake in radiation necrosis to that in normal cortex was much lower than the corresponding ratios for 18F-FDG and 18F choline, supportive of its potential for differentiating radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence.Citation146

In the last decade, studies on combined 18F-FET and MRI have shown improved identification of tumor tissue as compared with either modality alone.Citation147,Citation148 The specificity of distinguishing gliomas from normal tissue could be increased from 68% with the use of MRI alone to 97% with the use of MRI in conjunction with 18F-FET PET and MRI spectroscopy.Citation149

Nucleic acid analogs – 18F-FLT

The pyrimidine analog, 18F-FLT, is a PET radiotracer specifically used for noninvasive in vivo evaluation of the cell proliferation rate. 18F-FLT reflects the activity of thymidine kinase-1 during phase S of DNA synthesis.Citation15018F-FLT, introduced by Shields et al for PET imaging of tumor proliferation in animals and humans,Citation151 has been used in both preclinical and clinical studies.Citation152,Citation153 Transport of 18F-FLT is mediated by both passive diffusion and Na+-dependent carriers. The tracer is subsequently phosphorylated by thymidine kinase 1 (TK1) into 18F-FLT-monophosphate, where TK1 is a principal enzyme in the salvage pathway of DNA synthesis. Whereas the TK1 activity is virtually absent in quiescent cells, its activity reaches the maximum in the late G1 and S phases of the cell cycle in proliferating cells.Citation154 The phosphorylation of the tracer by TK1, therefore, makes 18F-FLT a good marker for tumor proliferation.

Recent findings suggest that 18F-FLT is a promising biomarker for differentiating between radiation necrosis and tumor recurrence ().Citation155,Citation156 A study by Hatakeyama et alCitation155 showed its superiority over 11C-MET in tumor grading. Chen et al demonstrated 18F-FLT PET as a promising imaging biomarker that seems to be predictive of OS in bevacizumab and irinotecan treatment of recurrent gliomas in which both early and later 18F-FLT PET responses were more significant predictors of OS compared with the MRI responses.Citation157 In addition, a recent prospective study by Schwarzenberg et alCitation158 showed that 18F-FLT uptake was highly predictive of PFS and OS in patients with recurrent gliomas on bevacizumab therapy (Avastin®; Genentec, South San Francisco, CA, USA; a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF, a protein released by tumor cells to recruit novel blood vessels to support tumor growth),Citation159,Citation160 and that 18F-FLT PET seems to be more predictive than MRI for early treatment response.

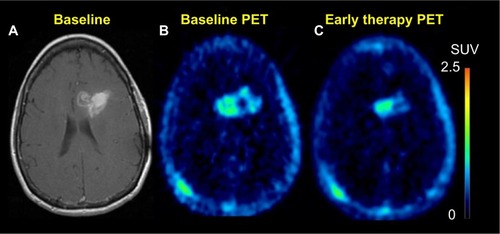

Figure 7 18F-FLT PET.

Notes: Sixty-five-year-old female who initially presented with glioblastoma multiforme, now presents after completion of 6 weeks of temozolomide chemotherapy and a total of 60 Gy radiotherapy to the tumor. T1 post-contrast enhanced images (A) demonstrate slight progression as compared to prior study. However, FLT uptake post-therapy (C) was significantly decreased as compared to baseline scan (B). This finding was suggestive of a response to therapy.

Abbreviations: FLT, fluoro-3′-deoxy-3′-l-fluorothymidine; PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standardized uptake value.

Hypoxia imaging – 18F-fluoromisonidazole

18F-Fluoromisonidazole is a nitroimidazole derivative PET agent used to image hypoxia,Citation161 a physiologic marker for tumor progression and resistance to radiotherapy (RT).Citation162 Its preferential uptake in high-grade rather than low-grade gliomas,Citation163 a significant relationship with upregulation of angiogenic markers such as VEGF receptor 1,Citation164 and correlation to progression and survival after RT,Citation165 suggest its potential role in monitoring response to therapy targeting hypoxic tissue.

Biopsy

A tissue diagnosis can be obtained at the time of surgical resection or through stereotactic biopsy. Biopsy alone is used in situations where the lesion is not amenable to resection, or when a meaningful amount of tumor tissue cannot be resected, or the patient’s overall clinical condition will not permit invasive surgery.

Stereotactic image-guided brain biopsy is an accurate and safe diagnostic procedure in patients with focal lesions.Citation166,Citation167 The combined use of computerized imaging and stereotactic framing devices allows neurosurgeons to perform deep brain biopsies with continuous and accurate intraoperative tumor localization. Frameless stereotaxy establishes a computerized link between the preoperative three-dimensional tumor volume and the surface landmarks of the patient. This link permits the neurosurgeon to be aware of the three-dimensional position of surgical instruments within the intracranial space during the biopsy based upon the preoperative imaging, with an accuracy of 1 mm within the intracranial space.

Treatment

After decades of minimal incremental advances in outcomes for multimodality treatment of malignant gliomas, the last decade has seen a series of transformative clinical trials establish new standards of care. At the same time, the limitations of these transformative strategies have raised new questions for therapeutic clinical trials. Addressing these questions requires innovative neuroimaging strategies to better assess treatment response. The application of molecular neuropathology, quantitative imaging of tumor response, and systematic evaluation of molecularly targeted therapies, as well as cytotoxic chemotherapy are expected to improve outcomes even further.

Surgery

Surgical resection has been a critical component of the multimodality management of malignant gliomas since the advent of modern neurosurgery and the original case series by Cushing and Dandy.Citation168 The role of neurosurgery has expanded in recent years to include techniques for intratumoral delivery of drugs, monoclonal antibodies, viral gene vectors, and immunotherapeutics. Resection or image-guided techniques for accessing the tumor microenvironment are increasingly critical components of therapeutic clinical trials as they help to show drug delivery to the tumor site and to verify that the anticipated physiologic effects relevant to the mode of action of the drug have occurred.Citation169,Citation170 In the era of molecularly-targeted therapies and personalized therapeutics, determination of the pattern of genetic and epigenetic changes in tumor tissue is critical to understanding the mechanisms of tumor response and resistance.Citation171

For GBM patients, there is compelling, though not level-one evidence, that maximal resection of newly diagnosed tumor improves survival.Citation172–Citation174 For anaplastic astrocytoma and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, the survival benefit of aggressive surgical resection is less clearly documented, but expert consensus supports similar resection goals as for GBM patients.Citation175 Maximal surgical resection provides the advantages of rapid cytoreduction, relief of symptoms related to mass effect, allows for institution of fractionated radiation therapy and chemotherapy with reduced target volumes, and provides tissue for diagnosis.Citation168

Image-guided resection and the incorporation of functional MRI information as well as intraoperative mapping has allowed for resection of tumors in close proximity to eloquent cortical structures and expanded the indications for resection.Citation176–Citation181 Innovations in MRI design have allowed for intraoperative MRI, in which the neurosurgeon can assess completeness of resection prior to closure of the craniotomy.

Minimally invasive neurosurgical techniques, exemplified by endoscopic resection techniquesCitation182 are being applied to resection of malignant gliomas, facilitating more complete resection of deeply located tumors, and intraventricular or periventricular tumors.Citation183 Neurosurgical techniques for intratumoral drug delivery are also being investigated. Stereotactic MRI or CT-guided techniques allow for biopsy and intratumoral delivery of therapeutic agents, though limited capacity for diffusion limits this technique in most settings. Microdialysis catheters placed at the time of tumor resection allow direct measurement of drug pharmacodynamics in clinical trials of systemically administered agents.

RT

Shortly after the initial attempts to control malignant gliomas with aggressive surgical resection, neurosurgeons and oncologists turned to EBRT as the second component of multimodality therapy. Seminal clinical trials by the early brain tumor clinical trial collaborative groups demonstrated that EBRT prolongs survival as compared with surgery alone, for GBM, anaplastic astrocytoma, and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas.Citation184–Citation186 Collaborative group trials established optimal dose and fractionation schema for the different histologies and grades of malignant tumors.

Involved field radiation therapy, which involved delivery of RT only to involved regions of the brain, has become the standard approach for adjuvant RT. The rationale for limiting the RT field is based upon the observation that, following whole brain radiation therapy, recurrent malignant gliomas develop within 2 cm of the original tumor site in 80%–90% of cases, while fewer than 10% are multifocal.Citation187–Citation189 To encompass infiltrating tumor cells, the RT dose of typically 60 Gray is usually delivered to the tumor plus a margin of radiographically apparently normal tissue. If the tumor is defined based upon contrast enhancement, a margin of 2.0 to 3.0 cm is often used, while if the RT field is defined by T2-weighted MRI abnormality, a 1.0 to 2.0 cm margin is used.

Over the past 3 decades, innovations in computer-based three-dimensional treatment planning have led to an increase in conformal radiation therapy. In academic centers of excellence, as well as in the community, these techniques have provided a new approach to treat malignant gliomas using an increased dose with less morbidity. Current three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy utilizes CT-based treatment planning with dosimetric software to create composite treatment plans. The fusion of planning CT with MRI is extremely helpful in assisting with target definition.Citation190,Citation191 The incorporation of PET or MRS data is still largely investigational and most commonly used to define boost volumes rather than primary target volumes. Photons of 6 to 8 MV are most commonly used with three to four angled radiation fields. Radiation oncologists work with medical physicists and dosimetrists to design optimal treatment plans. Optimization requires the consideration of beam energy, field size and shape, beam modifiers, irradiated tissue density and heterogeneity, and radiation tolerance of surrounding normal tissues. No benefit in PFS or OS has been demonstrated, although these techniques help avoid excess RT to normal brain.Citation192,Citation193

In the past several years, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), at least for academic radiation oncology centers, has been the technique of choice due to the elegance and precision of the dosimetry, especially if the tumor is in close proximity to radiosensitive structures such as the optic nerve. The IMRT technique uses advanced technology to manipulate beams of radiation to conform to the shape of a tumor. It uses nonuniform small radiation beams of varying intensities to deliver a treatment plan that maximizes the homogenous delivery of radiation to the intended treatment volume, while minimizing irradiation to normal tissue outside the target. The radiation intensity of each beam is controlled, and the beam shape changes throughout each treatment. The goal of IMRT is to bend the radiation dose to avoid or reduce exposure of healthy tissue and limit the side effects of treatment. The application of IMRT in the treatment of malignant gliomas has become increasingly prevalent as it may decrease radiation-related adverse effects.Citation194 IMRT can also be used to escalate doses to the tumor, but there are no proven benefits to delivering doses beyond 60 Gray.Citation195 The most appropriate application of IMRT in the brain will likely be when the radiation target abuts radiation-sensitive structures such as the eyes, optic nerves, optic chiasm, or brainstem. The disadvantages of IMRT include increased radiation scattering to surrounding non-target tissues and the complexity of radiation planning, which requires adaptation of the hardware of linear accelerators, skilled physicist support, and increased delivery time for treatment.

Despite decades of trials investigating permutations of total dose and fractionation schemes, the typical one per day treatment with external beam, 5 days per week, has remained the standard of care. With present technologies and strategies for radioprotection of normal structures, improvements in survival are unlikely to result from modifications in total dose or fraction size.

Proton beam RT is being investigated in the treatment of low-grade gliomas, medulloblastomas and ependymomas, and in malignant gliomas. At present, there is no level-one evidence that proton beam therapy improves survival in either the newly diagnosed or recurrent setting for GBM or anaplastic astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma. As with IMRT, proton techniques may have a specialized role in treatment of targets close to critical radiosensitivestructures.

Stereotactic radiosurgery has been used to boost fractionated RT for the treatment of newly diagnosed GBM following either biopsy or resection.Citation196–Citation198 Stereotactic radiosurgery uses three-dimensional planning techniques to precisely deliver narrowly collimated beams of ionizing radiation in a single high-dose fraction to small (<4 cm) intracranial targets. When this approach is divided into several factions it is called stereotactic RT.

In some centers, Gamma Knife radiosurgery is used, in which a hemispherical compartment with an array of cobalt-60 sources is the source of collimated beams. The Gamma Knife uses a fixed frame to stabilize the head relative to the radiation sources.

Frameless linear-accelerator-based stereotactic radiosurgery employs a linear accelerator that moves in multiple arcs around the target volume. The linear accelerator techniques do not employ a fixed frame, and the relationship of the target volume to the radiation source is determined by registration of fiducials.

Radiosurgery has transformed the treatment of brain metastasis and benign tumors such as acoustic schwannoma, but has yet to claim a clear role in the treatment of malignant gliomas.Citation199–Citation202 In the newly diagnosed setting, radiosurgery in conjunction with fractionated EBRT has not improved survival outcomes. However, in the recurrent setting, radiosurgery is an FDA-approved treatment modality, but progression at the margin of the target is a ubiquitous pattern of failure. More recently, radiosurgery has been combined with bevacizumab therapy. Initial institutional Phase II trials of this combination have not demonstrated superior time-to-progression or OS than either treatment alone, but some patients have durable tumor control.Citation203 The nuances in designing treatment fields may be critical in this setting.Citation204

Chemotherapy/drug therapy

The current standard of care for newly diagnosed GBM combines surgical resection, RT and adjuvant temozolomide treatment, leading to an increased median survival timeCitation205 of approximately 14.6 months. The EORTC trialCitation206 established that concomitant low-dose temozolomide and external beam fractionated radiation followed by adjuvant temozolomide results in a survival benefit to the chemotherapy arm versus radiation alone. The trial demonstrated a benefit in OS to the group receiving chemotherapy, and a tripling of the percentage of patients alive 2 years after therapy. Subsequent prospective trials showed that a dose-intensive adjuvant temozolomide regimen in which patients received 75 mg/m2 daily for 21 days followed by a 7-day rest was not superior to the shorter monthly courses of temozolomide.

Management of newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma is now based on level-one evidence. Two prospective randomized trials comparing external beam radiation alone to radiation therapy plus alkylator-based adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy were initially reported as showing no survival benefit with the addition of chemotherapy.Citation11,Citation13 However, long-term follow-up demonstrated that for patients with tumors expressing 1p/19q deletions, chemotherapy confers a significant survival advantage.Citation11,Citation13 The predictive value of the 1p deletion status makes this one of the first robust predictive biomarkers for malignant gliomas. In addition to the impact of 1p deletion status on outcome, these anaplastic oligodendroglioma studies also led to the delineation of subgroups of tumors with prognostic significance using microarray genome-wide expression analysis.Citation207 It is clear that future studies of anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and astrocytomas will need to include stratification by prognostic subgroups.

For newly diagnosed anaplastic astrocytoma, the optimal application of radiation and chemotherapy is an active clinical trial question.Citation208 The EORTC and the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) are conducting a randomized prospective trial comparing fractionated radiation therapy alone, to 1) radiation followed by adjuvant temozolomide, to 2) concurrent chemoradiation without subsequent adjuvant therapy, and to 3) the regimen of concurrent chemoradiation followed by adjuvant chemotherapy that is the standard treatment for GBM.Citation209,Citation210 In addition, these prospective randomized trials are stratifying tumors based on MGMT promoter methylation status and molecular biomarkers.Citation208

For patients with recurrent GBM, treatment outcomes are poor; the median time to tumor progression is 9 weeks, and the median survival is 25 weeks.Citation211 PFS is correlated with OS and has become the benchmark for assessing treatment efficacy in patients with recurrent GBM in whom the PFS-6 rate ranges between 9% and 15%.Citation211–Citation213 For recurrent GBM and anaplastic astrocytoma, the transformative trials involve the use of anti-angiogenic drugs.Citation214 The RTOG has completed two prospective randomized trials; one comparing two different adjuvant temozolomide regimens and another evaluating the efficacy of bevacizumab.Citation215,Citation216

Glioblastomas due to expression of a variety of pro-angiogenic factors are among the most vascular tumors. Angiogenesis is a critical process in the progression of gliomas.Citation217 One of the main determinants of angiogenesis is VEGF, which is secreted by glioma cells to induce the tumor vascularization that in turn facilitates growth of the tumor.Citation218 High expression of VEGF is correlated with poor clinical outcome, and it has been demonstrated that inhibition of VEGF decreases the growth of glioma cell lines.Citation219 High-grade gliomas with a high degree of VEGF expression and vessel density respond best to anti-angiogenic therapy.Citation220

Bevacizumab is an anti-angiogenic agent for GBM and received accelerated FDA approval for use in patients with recurrent GBM in 2009.Citation221 Bevacizumab (Avastin) is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds VEGF, thereby preventing the interaction of VEGF with its receptors VEGF receptor 1 and VEGF receptor 2. Blocking VEGF activity halts angiogenesis. The half-life of bevacizumab is approximately 20 days, so it is administered every 2 weeks and sometimes every 3 weeks. In Phase II studies in previously treated patients with malignant glioma, bevacizumab reduced requirements for steroids and was associated with imaging evidence of tumor response. These results have led to approval of bevacizumab for recurrent malignant glioma as well as investigation of bevacizumab as a component of initial combined modality therapy.Citation222

Bevacizumab has demonstrated significant activity in Phase II trials.Citation221 Bevacizumab alone or in combination with irinotecan resulted in response rates and time-to-progression that were substantially superior to historical controls with a range of cytotoxic regimens, and superior to results with any other molecularly-targeted drug therapy evaluated previously.Citation223 However, the value of bevacizumab in the treatment of recurrent GBM remains uncertain since responses in GBM trials have not been durable. Norden et alCitation224 compared PFS and OS of patients treated with bevacizumab with two contemporaneous trials of cytotoxic chemotherapy testing gimatecan and edotecarin. Median PFS in the bevacizumab cohort was 22 weeks, compared to only 8 weeks for the chemotherapy cohorts, and PFS-6 was 40% versus 11%. However, median OS was only 37 weeks in the bevacizumab cohort versus 39 weeks for the chemotherapy cohorts.Citation224 Bevacizumab appears to have an effect on PFS, but only modest effects on OS.Citation225 When patients progress through bevacizumab, the prognosis is dismal, with PFS of subsequent therapies being 4 weeks and PFS-6 being only 14%.Citation226,Citation227 Current and future trials evaluating combination therapies with molecularly-targeted drugs and bevacizumab have evolved a template structure in which bevacizumab is administered every 2 weeks in 28-day cycles, and the investigational agent is added to the monthly cycles with the scheduling dependent upon the biologic effect of the agent.

Although bevacizumab clearly produces a clinical improvement by decreasing the size of the contrast-enhancing mass lesion as well as ameliorating perilesion edema, the extent to which the drug is modifying the physiology of the BBB rather than killing tumor cells remains complex. When tumors progress after exposure to bevacizumab, subsequent therapies with cytotoxic chemotherapy are uniformly ineffective. In current practice, there is an emerging consensus that bevacizumab should be reserved for patients in whom the tumor is causing neurologic symptoms due to its size and surrounding edema.Citation228 The ability of bevacizumab to suppress the early toxicities of radiation therapy has facilitated re-exploration of reirradiation with fractionated external beam techniques as well as radiosurgery for recurrent malignant gliomas. Several institutional trialsCitation229,Citation230 have reported results of combining radiosurgery with Avastin in recurrent GBM and anaplastic astrocytoma. Although bevacizumab clearly reduces the early perilesion edema associated with radiosurgical treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas and produces radiologic responses by RANO criteria, it remains unproven whether the combination of radiosurgery and Avastin produces a more durable response, as measured by OS, than radiosurgery or bevacizumab alone.

Preliminary randomized Phase III trial results do not recommend the routine use of bevacizumab in combination with standard RT and temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma.Citation231,Citation232 This recommendation is based on the lack of proven survival benefit for bevacizumab when used as part of initial therapy and the increased risk of toxicity associated with combination therapy. Certain subsets of patients may ultimately be shown to benefit from early use of bevacizumab, such as those patients with bulky, nonresectable tumors, but further study is needed. Preliminary results from two Phase III clinical trialsCitation231,Citation232 assessing the role of bevacizumab in conjunction with RT plus temozolomide include the AVAglio study, in which 921 patients were randomly assigned to receive bevacizumab or placebo in conjunction with RT and temozolomide.Citation231 After completion of RT, patients were treated with six cycles of monthly temozolomide plus bevacizumab or placebo every 2 weeks, followed by maintenance bevacizumab or placebo every 3 weeks until progression. At the time of the preliminary analysis, 76% of the expected events had occurred. They concluded that median PFS was improved in patients treated with bevacizumab compared with placebo (10.6 versus 6.2 months; hazard ratio 0.64, 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.74). However, median OS was not significantly different (hazard ratio 0.89, 95% confidence interval 0.75 to 1.07). As well, there was an increase in the rate of serious adverse events in patients treated with bevacizumab.

In the RTOG 0825 study, 637 patients were randomly assigned to receive bevacizumab or placebo starting at week 4 of standard chemoradiation with temozolomide, followed by six to 12 cycles of maintenance temozolomide plus bevacizumab or placebo.Citation232 The conclusion was that PFS was extended in patients treated with bevacizumab (10.7 versus 7.3 months; P=0.004), but the result did not meet the predefined significance threshold of P<0.002. Median OS did not differ in patients treated with bevacizumab compared with placebo (15.7 versus 16.1 months, P=0.11). Notably, MGMT promoter methylation was strongly associated with improved PFS (14 versus 8 months for methylated versus unmethylated promoter, respectively) and OS (23 versus 14 months, respectively). In the subset of patients whose tumors exhibited both MGMT promoter methylation and a favorable nine-gene signature, there was a trend towards worse survival in patients treated with bevacizumab compared with placebo (15.7 versus 25 months, P=0.08). In addition, there was an increased rate of serious adverse events in patients treated with bevacizumab; primarily neutropenia, hypertension, and thromboembolism.

For recurrent anaplastic astrocytomas, the optimal chemotherapy regimens remain an active clinical trial question. A randomized prospective trialCitation233 for anaplastic astrocytomas at first relapse after fractionated RT alone compared the older regimen PCV to standard (150–200 mg/m2/day for days 1–5 of 28-day cycles) temozolomide and dose-intensive temozolomide (75 mg/m2/day for days 1–21 of 28-day cycles). The day 1–5 regimen was not inferior to PCV, but the more dose-intense regimen was counterintuitively less effective. The optimal regimens for patients relapsing after prior chemoradiation or adjuvant chemotherapy remain to be determined.

For recurrent anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, alkylator-based chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, but as for astrocytomas, the optimal regimen and schedules are currently being pursued.Citation12,Citation234–Citation236 A study by LassmanCitation12 of anaplastic oligodendrogliomas suggest that for 1p/19q deleted tumors, the older PCV regimen may be associated with better outcomes. Despite this retrospective data, temozolomide continues to be more widely used in the US.

Despite a quarter century of disappointing results and evidence that the malignant gliomas microenvironment was inhospitable to cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells, a relentless cadre of investigators has produced Phase II data suggesting that vaccine immunotherapy strategies can produce antitumor immune responses.Citation237 In a study of newly diagnosed GBM tumors expressing the EGFRvIII oncoprotein antigen, an anti-EGFRviii dendritic cell vaccine demonstrated improved time-to-progression and OS as compared with a contemporaneous historical control data set.Citation238 With all the caveats pertaining to historical control analysis and potential differences in distribution of molecular prognostic subgroups, vaccine therapies are demonstrating sufficient evidence of efficacy to warrant Phase III trials. As with clinical trials evaluating anti-angiogenic agents, criteria for determining tumor response and progression must be adapted to account for transient immune-mediated inflammatory responses that might be mistaken for development of tumor progression.Citation239

Summary

In recent times, there has been important progress in our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of malignant gliomas, leading to the development of targeted chemotherapeutic agents. Additionally, advances in diagnostic imaging have allowed for early diagnosis and treatment of malignant gliomas. As our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis and molecular imaging improves, it may be possible to select the most appropriate therapies on the basis of the patient’s tumor genotype. Furthermore, quantitative imaging biomarker assessment in the early phase of clinical trials could provide a novel approach for testing new therapies, and importantly, for facilitating patient management, sparing patients from weeks or months of toxicity due to ineffective treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was support by the US National Institutes of Health research grant U01 CA140230, as well as the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute shared resources award P30CA047904. We also acknowledge the editorial support from Ms Moira Hitchens, Administrator, Department of Radiology, University of Pittsburgh.

This work was performed at the Department of Radiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FerlayJShinHRBrayFFormanDMathersCParkinDMEstimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008Int J Cancer2010127122893291721351269

- LouisDNOhgakiHWiestlerODThe 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous systemActa Neuropathol200711429710917618441

- OstromQTGittlemanHFarahPCBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States 2006–2010Neuro-Oncol201315sup 2ii1ii5624137015

- KleihuesPLouisDNScheithauerBWThe WHO classification of tumors of the nervous systemJ Neuropathol Exp Neurol2002613215225 discussion 226–22911895036

- FisherJLSchwartzbaumJAWrenschMWiemelsJLEpidemiology of brain tumorsNeurol Clin2007254867890 vii17964019

- Barnholtz-SloanJSSloanAEDavisFGVigneauFDLaiPSawayaREIncidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance SystemJ Clin Oncol200422142865287215254054

- DavisFGDolecekTAMcCarthyBJVillanoJLToward determining the lifetime occurrence of metastatic brain tumors estimated from 2007 United States cancer incidence dataNeuro Oncol20121491171117722898372

- GuptaKSalunkePMolecular markers of glioma: an update on recent progress and perspectivesJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol2012138121971198123052697

- OlarAAldapeKDBiomarkers classification and therapeutic decision-making for malignant gliomasCurr Treat Options Oncol201213441743622956341

- ClarkKHVillanoJLNikiforovaMNHamiltonRLHorbinskiC1p/19q testing has no significance in the workup of glioblastomasNeuropathol Appl Neurobiol201339670671723363074

- CairncrossGWangMShawEPhase III trial of chemoradiotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term results of RTOG 9402J Clin Oncol201331333734323071247

- LassmanABSuccess at last: a molecular factor that informs treatmentCurr Oncol Rep2013151475523247800

- van den BentMJBrandesAATaphoornMJAdjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term follow-up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951J Clin Oncol201331334435023071237

- BelloMJde CamposJMKusakMEAllelic loss at 1p is associated with tumor progression of meningiomasGenes Chromosomes Cancer1994942962987519053

- ReifenbergerJReifenbergerGLiuLJamesCDWechslerWCollinsVPMolecular genetic analysis of oligodendroglial tumors shows preferential allelic deletions on 19q and 1pAm J Pathol19941455117511907977648

- IchimuraKMolecular pathogenesis of IDH mutations in gliomasBrain Tumor Pathol201229313113922399191

- HartmannCHentschelBWickWPatients with IDH1 wild type anaplastic astrocytomas exhibit worse prognosis than IDH1-mutated glioblastomas, and IDH1 mutation status accounts for the unfavorable prognostic effect of higher age: implications for classification of gliomasActa Neuropathol2010120670771821088844

- OlsonRABrastianosPKPalmaDAPrognostic and predictive value of epigenetic silencing of MGMT in patients with high grade gliomas: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Neurooncol2011105232533521523485

- HegiMEDiserensACGorliaTMGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastomaN Engl J Med200535210997100315758010

- BrandesAAFranceschiETosoniAMGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patientsJ Clin Oncol200826132192219718445844

- OhgakiHKleihuesPGenetic pathways to primary and secondary glioblastomaAm J Pathol200717051445145317456751

- OlarARaghunathanAAlbarracinCTAbsence of IDH1-R132H mutation predicts rapid progression of nonenhancing diffuse glioma in older adultsAnn Diagn Pathol201216316117022197544

- VerhaakRGHoadleyKAPurdomECancer Genome Atlas Research NetworkIntegrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1Cancer Cell20101719811020129251

- PhillipsHSKharbandaSChenRMolecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesisCancer Cell20069315717316530701

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research NetworkComprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathwaysNature200845572161061106818772890

- NoushmehrHWeisenbergerDJDiefesKCancer Genome Atlas Research NetworkIdentification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of gliomaCancer Cell201017551052220399149

- GanHKKayeAHLuworRBThe EGFRvIII variant in glioblastoma multiformeJ Clin Neurosci200916674875419324552

- MellinghoffIKSchultzNMischelPSCloughesyTFWill kinase inhibitors make it as glioblastoma drugs?Curr Top Microbiol Immunol201235513516922015553

- MellinghoffIKCloughesyTFMischelPSPTEN-mediated resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor kinase inhibitorsClin Cancer Res2007132 Pt 137838117255257

- KimYHNonoguchiNPaulusWFrequent BRAF gain in low-grade diffuse gliomas with 1p/19q lossBrain Pathol201222683484022568401

- SalamaAKFlahertyKTBRAF in Melanoma: Current strategies and future directionsClin Cancer Res201319164326433423770823

- Hoang-XuanKCapelleLKujasMTemozolomide as initial treatment for adults with low-grade oligodendrogliomas or oligoastrocytomas and correlation with chromosome 1p deletionsJ Clin Oncol200422153133313815284265

- HegiMELiuLHermanJGCorrelation of O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation with clinical outcomes in glioblastoma and clinical strategies to modulate MGMT activityJ Clin Oncol200826254189419918757334

- Haas-KoganDAPradosMDTihanTEpidermal growth factor receptor, protein kinase B/Akt, and glioma response to erlotinibJ Natl Cancer Inst2005971288088715956649

- MellinghoffIKWangMYVivancoIMolecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitorsN Engl J Med2005353192012202416282176

- RichJNReardonDAPeeryTPhase II trial of gefitinib in recurrent glioblastomaJ Clin Oncol200422113314214638850

- KienastYvon BaumgartenLFuhrmannMReal-time imaging reveals the single steps of brain metastasis formationNat Med201016111612220023634