Abstract

Recent advances in the understanding of immunology and antitumor immune responses have led to the development of new immunotherapies, including vaccination approaches and monoclonal antibodies that inhibit immune checkpoint pathways. These strategies have shown activity in melanoma and are now being tested in lung cancer. The antibody drugs targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 and programmed cell death protein-1 immune checkpoint pathways work by restoring immune responses against cancer cells, and are associated with unconventional response patterns and immune-related adverse events as a result of their mechanism of action. As these new agents enter the clinic, nurses and other health care providers will require an understanding of the unique efficacy and safety profiles with immunotherapy to optimize potential patient benefits. This paper provides a review of the new immunotherapeutic agents in development for lung cancer, and strategies for managing patients on immunotherapy.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

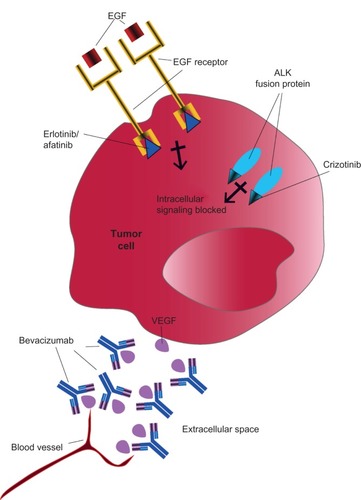

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the US.Citation1 Approximately 85% of cases are non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and the majority of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage of disease.Citation2 Unfortunately, current treatment options for NSCLC are limited. Historically, most patients in the US receive platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment.Citation3 A small population of patients are also candidates for treatment with targeted agents; however, most patients eventually develop resistance to targeted agents.Citation3,Citation4 Erlotinib (Tarceva®, OSI Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Farmingdale, NY, USA), afatinib (Gilotrif®, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ridgefield, CT, USA), and crizotinib (Xalkori®, Pfizer, Inc, New York, NY, USA) are approved first-line therapies for patients expressing particular mutations in the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, or with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive tumors, respectively. Patients with non-squamous NSCLC without a recent history of hemoptysis may be treated with bevacizumab (Avastin®, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA) in combination with doublet therapy. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits angiogenesis of the tumor, leading to tumor starvation. Docetaxel, pemetrexed, and erlotinib are approved second-line therapies.Citation3

Even with treatment, 5-year survival rates average 17% for patients with early disease and 4% for patients diagnosed with metastatic disease.Citation1,Citation2 Current chemotherapies work by acting non-selectively, targeting cell division or cell suicide pathways to encourage tumor cell death.Citation5 Targeted agents inactivate specific mutated proteins that confer growth advantages to the tumor; however, only a percentage of patients express these mutations, ie, 10%–15% for EGF receptor mutations and 2%–7% for ALK mutations.Citation6–Citation9 In contrast, immunotherapies are designed to restore, stimulate, or enhance the ability of the immune system to recognize and eliminate tumors, and in initial trials, immunotherapies have shown activity in NSCLC and other cancer types.Citation10–Citation14 Herein, new therapeutic approaches for NSCLC are reviewed, focusing on immunotherapy.

Tumor immunology

The immune system primarily functions to protect the body from damage caused by pathogens. However, the immune system also serves to detect and eliminate aberrant cells, including cancer cells, which could potentially cause harm.Citation15 This is evidenced by the finding that patients with reduced immune function as a result of acquired immune deficiency syndrome or chronic immunosuppression have increased rates of malignancy.Citation16 T-cells eliminate tumors by recognizing aberrant proteins presented by cancerous cells, and coordinating an immune response against them.Citation15 Immune responses, whether against tumor cells, infected cells, or as a result of autoimmunity, can damage healthy tissue if left unchecked. To protect against this, the immune system has multiple mechanisms to downregulate immune responses – collectively known as immune checkpoint pathways.

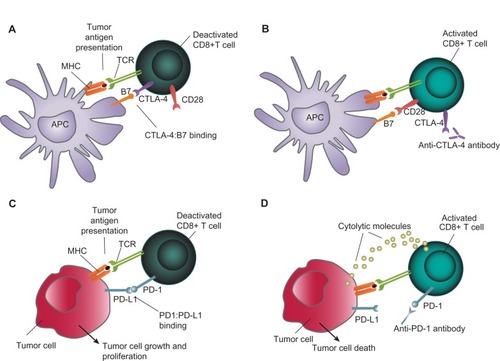

The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) pathways are two of several immune checkpoint pathways that play critical roles in controlling T-cell immune responses. CTLA-4 and PD-1 are expressed by T-cells. When they bind their ligands (CD80 and CD86 [B7 molecules] for CTLA-4; programmed death ligand-1 [PD-L]1 and PD-L2 for PD-1), the T-cell effector functions are dampened or stopped, and the T-cell can become nonresponsive.Citation17 CTLA-4 is thought to act in the early stages of an immune response, primarily to reduce T-cell responses to self antigens and prevent autoimmunity.Citation17 In contrast, PD-1 functions in the later stages of an immune response to stop ongoing immune activity in tissues.Citation17

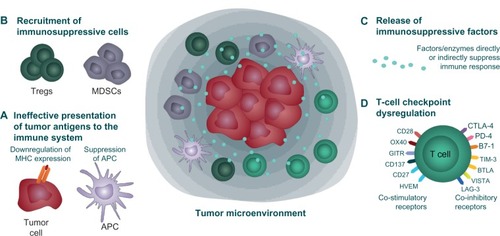

Some tumors evade immune responses by exploiting immune checkpoint pathways and other regulatory mechanisms ().Citation18–Citation23 A better understanding of these immune evasion strategies has given rise to novel immunotherapies that can restore the patient’s own immune system to respond to and eliminate cancer cells. These immunotherapies re-engage and allow T-cells to function appropriately against tumors.

Figure 1 Immune evasion or immunosuppressive strategies used by tumor cells.

Notes: Tumors use numerous strategies to evade immune responses.Citation18–Citation23 (A) Cancer cells can downregulate expression of MHC molecules that present tumor antigens to T-cells, and suppress tumor antigen presentation by professional APC, thereby avoiding recognition by T-cells. (B) Tumors create an immunosuppressive environment by recruitment and retention of suppressive Tregs and MDSCs, or (C) by secretion of immune-regulating or suppressive cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 and transforming growth factor-beta) and mediators (prostaglandins, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. (D) Dysregulation of T-cell checkpoint pathways, including expression of PD-L1 by tumors, sends negative signals to tumor-specific T cells, causing T cell inactivation.

Abbreviations: APC, antigen-presenting cells; IL, interleukin; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; Tregs, T-regulatory cells.

Rationale for immunotherapy in NSCLC

Immunotherapeutic approaches have been effective in some cancers. Both sipuleucel-T (Provenge™, Dendreon Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA) and ipilimumab (Yervoy™, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA) were approved based on significantly improved patient survival versus control treatment in clinical trials.Citation24–Citation27 Sipuleucel-T, approved for asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic metastatic castrate-resistant (hormone-refractory) prostate cancer, is a vaccination approach in which a patient’s own immune cells are removed, primed specifically against a prostate cancer antigen, and reintroduced into the patient’s body.Citation26,Citation27 Ipilimumab, approved in the US for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma, is a human monoclonal antibody that directly modulates the immune system by preventing CTLA-4 from binding its ligands.Citation24,Citation25

Historically, NSCLC has not been considered sensitive to immune-based therapies; however, data show lung tumors are recognized by the immune system, and a more robust antitumor immune response is associated with better survival. In clinical studies, higher numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T-cells, CD8+ T-cells, natural killer cells, and/or dendritic cells have been associated with improved patient survival.Citation28–Citation33 Nevertheless, the poor outcomes in NSCLC indicate that in many cases, the immune system is ultimately unable to completely destroy cancerous cells. This may be due to an immunosuppressive environment created by lung tumors, that hinders the ability of the immune system to eliminate NSCLC.Citation20,Citation34–Citation39 The observation that the immune system can recognize and respond to lung tumors, but is countered by immunosuppressive effects of the tumor, suggests that immunotherapies could work by harnessing the natural ability of immune cells to recognize and respond to lung cancer cells.

Immunotherapeutic approaches for NSCLC

Standard therapies for NSCLC act directly on cancer cells to inhibit tumor growth or cause tumor cell death. The mechanisms of action for chemotherapeutic agents include interrupting proper DNA synthesis, replication, and repair, or inhibiting normal cell division.Citation5,Citation40,Citation41 Erlotinib, afatinib, and crizotinib target proteins (the EGF receptor or ALK) that are aberrantly expressed or mutated in subsets of NSCLC cancers, predominantly in nonsquamous subtypes.Citation42–Citation44 These proteins confer a survival and growth advantage to the tumor; the targeted agents work to inactivate them and reduce the aggressiveness of the tumor.Citation4,Citation44,Citation45 Bevacizumab is thought to restrict tumor cell growth by inhibiting angiogenesis, thereby limiting the tumor’s blood supply; it may also enhance delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs to the tumor ().Citation46

Figure 2 Targeted therapy approaches in NSCLC. Targeted therapies work by inactivating proteins essential for tumor growth and survival. Both EGF receptor tyrosine kinase and ALK can be mutated and overactive in some patients with NSCLC, although not typically in the same patients. Erlotinib and afatinib inhibit the tyrosine kinase on the intracellular region of the EGF receptor and prevent growth signaling. Crizotinib inhibits the kinase activity of ALK, located in the cell cytoplasm, to prevent growth signaling. Bevacizumab binds and inactivates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secreted by the tumor into the intracellular space, thereby limiting blood vessel formation to the tumor.

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EGF, epidermal growth factor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

In contrast, immunotherapy acts on the patient’s own immune system, not the tumor. The therapeutic goals of immunotherapy are to modulate the immune system to recognize and attack the tumor. Strategies to actively enhance the immune response against NSCLC include vaccination to stimulate antibody and T-cell responses to cancer cells and use of immune checkpoint inhibitors to restart T-cell immune responses to NSCLC cells.

Vaccination strategies

Many vaccines for NSCLC have reached the Phase II or III trial stage of development, the majority of which pair cancer-associated antigen(s) with an immune-activating compound.

Melanoma-associated antigen A3

Melanoma-associated antigen A3 (MAGE-A3) is a tumor-associated antigen (ie, expressed on the surface of certain cancer cell types, but not normal cells), and is thus a good candidate for a vaccine.Citation47 In a study of patients with stage 1 or 2 NSCLC, MAGE-A3 was expressed by 39% of tumors.Citation47 A randomized, placebo-controlled Phase II trial tested a MAGE-A3 vaccine in patients with completely resected MAGE-A3-positive stage 1b–2 NSCLC.Citation48 After a median of 44 months, disease recurrence was slightly reduced in patients receiving the vaccine versus placebo (35% versus 43%), but there were no significant differences in disease-free interval or survival between the groups.Citation48 An ongoing Phase III trial in patients with completely resected MAGE-A3-positive stage 1b–3a NSCLC is evaluating disease-free survival after MAGE-A3 vaccination.Citation49

Mucinous glycoprotein-1

Mucinous glycoprotein-1 (MUC1) is another tumor-associated antigen that is commonly expressed in NSCLC, and often aberrantly expressed or glycosylated.Citation50 Two MUC1 vaccines, L-BLP25 and TG4010, have shown evidence of activity in clinical trials, and are being pursued in Phase III trials.

L-BLP25 (tecemotide, Stimuvax®) uses the BLP25 lipo-peptide of MUC1 and an adjuvant in a liposomal delivery system.Citation50,Citation51 In a Phase IIb trial in patients with stage 3b or 4 NSCLC who were stable or had responded to first-line chemotherapy, L-BLP25 following a low dose of cyclophosphamide was associated with improved median and 2-year survival, particularly in the subset of patients with stage 3b locoregional disease.Citation51 Two trials will evaluate overall survival in patients with nonresectable stage 3 NSCLC receiving best supportive care with L-BLP25 versus placebo, following a low dose of cyclophosphamide.Citation52,Citation53

TG4010 contains a genetically modified virus that expresses both MUC1 and interleukin-2, a cytokine which activates T-cells and natural killer cells.Citation54 TG4010 was evaluated in patients with stage 3b or 4 MUC1-positive NSCLC in conjunction with chemotherapy (cisplatin plus gemcitabine) in a Phase IIb study.Citation54 Six-month progression-free survival was higher with TG4010 versus chemotherapy alone (43% versus 35%). A Phase IIb/III trial of TG4010 (versus placebo) with first-line therapy in patients with stage 4 NSCLC is currently recruiting patients. Progression-free survival and overall survival will be evaluated.Citation55

Belagenpumatucel-L

Belagenpumatucel-L (Lucanix™, NovaRx Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) is a cellular vaccine composed of four types of NSCLC cell lines (two adenocarcinomas, one squamous carcinoma, and one large-cell carcinoma) that have reduced transforming growth factor-beta production as a result of genetic modification.Citation56 Three different doses of belagenpumatucel-L using the same vaccination schedule were tested in patients with stage 2–4 NSCLC after prior chemotherapy.Citation56 A dose-dependent survival advantage was seen, in that the estimated median survival time for patients receiving the two higher doses (combined) was significantly higher than for patients receiving the lowest dose (581 days versus 252 days; P=0.0186). The investigators reported that no significant adverse events were observed. A Phase III trial of the vaccine versus placebo in patients with advanced NSCLC who had previously received chemotherapy completed enrollment in 2012, but has not yet reported results.Citation57

Epidermal growth factor

The EGF receptor is overexpressed in many tumor types, including NSCLC, and signaling through this receptor is associated with cell proliferation, decreased cell death, cell migration, and angiogenesis.Citation4,Citation58 A vaccine (CimaVax-EGF) was designed to elicit an antibody response against EGF, an important ligand for the EGF receptor, in order to reduce EGF receptor signaling and limit tumor growth.Citation58 CimaVax-EGF was tested in patients with advanced NSCLC who had finished first-line therapy, and showed significant survival improvement in patients <60 years of age as compared with patients who did not receive the vaccine (median survival 11.6 months versus 5.3 months, P=0.0124). The vaccine was well tolerated, with no grade 3 or 4 adverse events reported.Citation58 A Phase III trial is currently being conducted in the UK, with an estimated completion date in 2015.Citation59 No US trials are ongoing.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Whereas vaccines are designed to stimulate tumor antigen-specific immune responses, immune checkpoint inhibitors, in theory, should “remove the brakes” on most T-cell-mediated immune responses. This mechanism of action has the risk of inducing immune-related reactions. In this section, the current data on the activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in NSCLC are reviewed, followed by separate sections on the incidence and management of select adverse events (adverse events with potential immunologic etiologies that require more frequent monitoring and/or unique intervention) observed with these therapies.

Anti-CTLA-4

Ipilimumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to CTLA-4 and prevents cytotoxic T-cell downregulation at early stages of T-cell activation. In patients with previously treated metastatic melanoma, ipilimumab therapy can improve survival.Citation25 In the pivotal trial, one-year survival was estimated at 46% of patients versus 22%–38% for patients with similar disease receiving other treatment regimens using historical data.Citation25 Approximately 24% of clinical trial patients with advanced melanoma treated with ipilimumab were alive at 2 years.Citation25 Using real-world data, one-year survival rates for patients with advanced melanoma treated with ipilimumab were estimated to be 49%–60%.Citation60,Citation61

The activity of ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin was evaluated in patients with chemotherapy-naïve advanced (stage 3b or 4) NSCLC.Citation62 Patients were randomized to a concurrent ipilimumab regimen (four doses of ipilimumab plus paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by two doses of placebo plus paclitaxel and carboplatin), a phased ipilimumab regimen (two doses of placebo plus paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by four doses of ipilimumab plus paclitaxel and carboplatin), or a control regimen (up to six doses of placebo plus paclitaxel and carboplatin). Ipilimumab or placebo, paclitaxel, and carboplatin were administered intravenously once every 3 weeks for a maximum of 18 weeks. Patients without progression received maintenance treatment with either ipilimumab (ipilimumab arms) or placebo (control arm) once every 12 weeks until progression, death, or intolerance.

Antitumor responses were highest in the phased ipilimumab group ().Citation62 Although the numbers were small in the trial, subset analyses suggested phased ipilimumab significantly improved the activity of chemotherapy in patients with squamous histology and no significant benefit for patients with nonsquamous histology.Citation62 Based on the promising results, a Phase III study of phased ipilimumab with chemotherapy has been initiated in patients with stage 4/recurrent squamous NSCLC.Citation63

Table 1 Clinical results of ipilimumab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with chemotherapy-naïve advanced (stage 3b or 4) NSCLC

Anti-PD-1

Blocking the PD-1 pathway is thought to modulate the activity of T-cells that have become nonresponsive after encountering PD-1 ligands in the tumor microenvironment ().Citation17,Citation64 There are currently two anti-PD-1 agents in advanced stages of development: nivolumab and MK-3475.

Figure 3 Concept of immunotherapy in NSCLC. (A) APCs display tumor antigens and B7 (CD80/CD86) molecules to CD8+ T-cells. CTLA-4 and CD28 are expressed on T-cells and compete for binding to B7. CTLA-4 has a higher affinity for B7 and CTLA-4:B7 binding leads to T-cell deactivation. (B) Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies prevent CTLA-4:B7 binding and allow CD28:B7 binding leading to T-cell activation. (C) Binding of PD-1 on T-cells to PD-L1 (or PD-L2; not depicted) on tumor cells causes T-cell deactivation. (D) Anti-PD-1 antibodies (or anti-PD-L1 antibodies, not shown) prevent PD-1:PD-L1 binding and restore T-cell activation and killing of tumor cells via release of cytolytic molecules.

Abbreviations: APCs, antigen-presenting cells; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4.

Nivolumab

Nivolumab (BMS-936558), a fully human IgG4 PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, is currently being evaluated in two Phase III trials for NSCLC after promising Phase I data. In the initial trial, nivolumab monotherapy was administered to patients with several tumor types, including 129 patients with NSCLC, nearly all of whom had received prior treatment.Citation12,Citation65 Patients received one of five different nivolumab doses, ranging from 0.1 mg/kg to 10.0 mg/kg every 2 weeks for up to 12 8-week cycles. In NSCLC patients, objective responses were observed in evaluable patients across doses of 1–10 mg/kg and across histologic subtypes in the initial analysis (). With extended treatment, the median response duration for the 3 mg/kg dose had not been reached at the time of analysis (range 16.1+ weeks to 133.9+ weeks). Median overall survival across all dose cohorts was 9.2 months for patients with squamous NSCLC and 10.1 months for those with nonsquamous NSCLC. At the 3 mg/kg dose, the median overall survival was 14.9 months (9.5 months for squamous NSCLC; 18.2 months for nonsquamous NSCLC), and this dose has been selected for Phase III trials. Data on overall survival rates are limited. Overall survival for NSCLC patients at one and 2 years was 42% and 24%, respectively. One-year survival was 39% for patients with squamous NSCLC and 43% for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC across all doses.Citation65

Table 2 Initial Phase I efficacy results for nivolumab monotherapy in evaluable patients with NSCLC

The tolerability and activity seen with nivolumab in previously-treated NSCLC patients, including 54% of patients with three prior lines of therapy, was notable and served as the basis for pursuing Phase III trials. The trials will evaluate efficacy (response rate and overall survival) of nivolumab versus docetaxel as a second-line therapy in patients with previously treated advanced stage or metastatic squamousCitation66 or nonsquamous NSCLC.Citation67 Additional Phase II studies are also ongoing, with objective response rate as their primary endpoint, testing nivolumab monotherapy as third-line treatment in patients with advanced or metastatic squamous NSCLC,Citation68 nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced or metastatic solid tumors, including NSCLC,Citation69 and nivolumab following azacitidine and entinostat versus oral azacitidine in patients with recurrent metastatic NSCLC.Citation70 A Phase I trial is testing nivolumab as monotherapy, maintenance therapy, or in combination with chemotherapy or targeted agents (erlotinib and bevacizumab), or with ipilimumab in patients with stage 3b/4 NSCLC.Citation71

MK-3475

MK-3475 is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds PD-1. A Phase I dose-finding study of MK-3475 showed a high response rate and durable responses in patients with advanced melanoma.Citation72 In patients with NSCLC who were previously treated with two systemic regimens, MK-3475 was administered at 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks. In an interim analysis of 38 patients, the objective response rate was 21%, and most responses had occurred by 9 weeks.Citation73 A Phase II/III study comparing MK-3475 and docetaxel has been initiated in patients with NSCLC that has progressed after platinum-containing therapy. The trial is evaluating a low and high dose of MK-3475, with overall survival, progression-free survival, and safety as the primary endpoints.Citation74

Anti-PD-L1

Anti-PD-L1 therapies also target the PD-1 pathway by binding one of its ligands, ie, PD-L1.

BMS-936559

BMS-936559 is a high-affinity, fully human, PD-L1-specific monoclonal antibody which showed activity against advanced NSCLC in a Phase I clinical trial that included multiple advanced tumor types.Citation75 Five of 49 evaluable NSCLC patients had an objective response; response duration ranged from 2.3+ months to 16.6+ months. Six of 49 patients had stable disease lasting $24 weeks, and 31% of patients had progression-free survival at 24 weeks.

MPDL3280A

Another anti-PDL1 antibody is MPDL3280A, which is a human monoclonal antibody containing an altered nonbinding domain.Citation76 A Phase I dose escalation/expansion study in multiple solid tumor types is being conducted to evaluate dose-limiting toxicities. In an interim analysis of 40 NSCLC patients who had received doses of 1–20 mg/kg, the response rate was 23%, and all responses were ongoing or improving at data cutoff (range 1+ to 214+ days). The rate of progression-free survival at 24 weeks was 46%.Citation76 Two Phase II studies with MPDL3280A are ongoing. One trial is monitoring objective responses and safety in patients with PD-L1-positive locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC receiving MPDL3280A monotherapy.Citation77 The other study is evaluating response rates and safety of MPDL3280A compared with docetaxel in patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC in whom platinum therapy has failed.Citation78

Immunotherapy combinations

Given the many agents with nonredundant mechanisms of action, immunotherapy combinations are being explored in cancer trials in the hope of superior efficacy over single agents. Preliminary evidence in advanced melanoma suggests that this might indeed be possible. A combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab in advanced melanoma showed that 53% of patients had an objective response, and these patients all had a reduction in tumor volume of 80% or more. In total, 65% of patients had evidence of clinical activity.Citation13

Trials of ipilimumab and nivolumab are now underway in NSCLC, including the one in patients with stage 3b/4 NSCLC mentioned above.Citation79 Two early (Phase I) trials in advanced tumors, including NSCLC, are evaluating nivolumab in combination with recombinant interleukin-21,Citation80 an immune-stimulating cytokine that has shown clinical activity in melanoma and renal cell carcinoma, and in combination with lirilumab (a natural killer cell-activating antibody).Citation81 Several approaches combining checkpoint inhibitors and vaccines are being investigated in numerous cancer types, but so far none are exclusively in NSCLC.Citation82

Immune-mediated responses and treatment decisions

As compared with chemotherapy, unconventional treatment responses have been observed with immunotherapy. These are also likely due to the immune mechanism of action, and can be associated with improved long-term patient outcomes.Citation83 In addition to shrinkage of baseline lesions in the absence of new lesions, the following immune-related response patterns have been described:

durable stable disease (in some patients followed by a slow, steady decline in total tumor burden)

reduced tumor burden after an increase in total tumor burden

overall reduced tumor burden in the presence of new lesions.

Increased tumor volume followed by tumor shrinkage has been called pseudoprogression. The increased tumor size may be caused by higher numbers of immune cells infiltrating the tumor. Also, as compared with chemotherapy, delayed responses are not uncommon, and likely due to the time it takes to generate effective antitumor immune responses.Citation25,Citation84 The health care provider will need to consider these potential response patterns in patients on immunotherapy when assessing the effectiveness of therapy and making treatment decisions.

Safety profile of immunotherapy

Immunotherapies stimulate the immune system with the goal of eradicating tumors, and some side effects are likely related to this immunologic mechanism of action. Inhibiting the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways will lead to activation of T-cells specific to tumor antigens and potentially to self antigens.Citation11 As such, certain adverse events in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors differ from chemotherapy-related adverse events. These events are termed select adverse events, and may require more frequent monitoring and/or unique intervention.

The most common types of select adverse events reported with checkpoint pathway inhibitors are listed in ,Citation12,Citation13,Citation25,Citation62,Citation65,Citation72,Citation73,Citation75,Citation76,Citation85,Citation86 and include gastrointestinal, dermatologic, and endocrine side effects. In clinical studies, select adverse events were reported in approximately 40%–60% of patients, including 3%–20% patients with grades 3 or 4. Select adverse events were reversible in most cases; however, some adverse event-related deaths occurred.Citation12,Citation25,Citation62,Citation65,Citation72,Citation73,Citation75 Differences in the incidence and type of grade 3–4 select adverse events across the different immunotherapy drugs were observed, and newer agents under investigation appear to have a better overall safety profile than ipilimumab. However, additional data are needed to confirm this observation.

Table 3 Examples of select adverse events reported with immune checkpoint inhibitorsCitation12,Citation13,Citation25,Citation62,Citation65,Citation72,Citation73,Citation75,Citation76,Citation85,Citation86

Overall, dermatologic select adverse events were the most frequently reported (12%–44%), followed by gastrointestinal events (9%–32%).Citation12,Citation25,Citation65,Citation73 Infusion-related reactions (3%–10%), endocrine disorders, including hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and hypophysitis (2%–8%), and pneumonitis (3%–6%) were also reported,Citation12,Citation25,Citation65,Citation72,Citation75 as were isolated cases of uveitis ().Citation13,Citation75 In a pilot study of combination therapy with both ipilimumab and nivolumab in melanoma, select adverse events occurred at a higher frequency, with 53% of patients experiencing a grade 3–4 event.Citation13 These select adverse events were generally reversible, although three patients (9%) discontinued therapy owing to treatment-related adverse events. No treatment-related deaths were reported in the study.Citation13

Management of select adverse events

Onset of immune-mediated side effects is variable and appears to depend on the organ system affected, although many occur during the first treatment cycles. Some, however, occur after a patient has been treated with several cycles. This is in keeping with the immune mechanism of action, as the time it takes to recognize antigens and build a response is inconsistent and may be prolonged. Also, delayed select adverse events can develop after a patient has completed or discontinued treatment, as the immune responses may persist. Thus, it is imperative for clinicians to continue to monitor for potential side effects.

Although most select adverse events with immunotherapies are of low grade, select adverse events can occur with rapid onset, and prompt medical attention is critical to the management of immune-related events.Citation25,Citation87 This requires a joint effort between health care providers, patients, and caregivers. Key strategies for successful management of select adverse events include the following:

early detection and continued screening for potential select adverse events

utilization of treatment algorithms for immune-mediated diarrhea/colitis, pneumonitis, and endocrine disorders (hypothyroidism, hypophysitis, and adrenal insufficiency)

ongoing education of staff nurses and support staff regarding the unique side effect profile

continual education of family members and caregivers to the unique side effect profile and encouragement of early notification of side effects

referral to specialists, ie, an endocrinologist, pulmonologist, and ophthalmologist.

Health care providers, patients, and caregivers should have a low threshold for acting on gastrointestinal symptoms for ipilimumab-treated patients, because the pathology and treatment are different than for chemotherapy-associated diarrhea.Citation86 Similarly, any exacerbation in pulmonary symptoms, even in patients with lung cancer, should be evaluated in patients who have received nivolumab, MK-3475, or other immunotherapy. The evidence suggests that progression to severe events may be avoided through proactive monitoring and early and sustained intervention.Citation86,Citation87 Any potential select adverse event should be treated with a high level of concern.

Clinical trial protocols and reports, and the ipilimumab prescribing information offer guidelines for the management of select adverse events that occur in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors, although it should be noted that, at present, only ipilimumab has an approved anticancer indication (advanced melanoma).Citation12,Citation13,Citation24,Citation25,Citation72,Citation75,Citation86,Citation87 These guidelines include:

evaluation/monitoring of thyroid and liver function tests prior to each ipilimumab dose

supportive antidiarrheals for grade 1 diarrhea

administration of corticosteroids if diarrhea progresses to grade 2

systemic high-dose corticosteroid treatment for severe, persistent, or recurring select adverse events; steroid taper is usually protracted to prevent rebound recurrence of select adverse events

a delay in a scheduled dose for moderate select adverse events until complete recovery, or discontinuation of therapy for severe reactions

use of replacement therapy for endocrine disorders, specifically thyroid replacement and steroid replacement.

Investigators in clinical trials used these strategies for effective management of select adverse events in most cases. In nivolumab trials, hepatic or gastrointestinal adverse events were managed with treatment interruption and, as necessary, with the administration of glucocorticoids. Also, early-grade pneumonitis in six nivolumab-treated patients was reversible with treatment discontinuation, glucocorticoid administration, or both. In three patients with pneumonitis, infliximab, mycophenolate, or both were used for additional immunosuppression, although the efficacy of this strategy was difficult to evaluate.Citation12 Glucocorticoid administration for select adverse events is usually continued on a slow taper following recovery to reduce recurrence. For pneumonitis, diarrhea or colitis, or adrenal insufficiency of more than grade 2, patients may require hospitalization. Referral to specialists (eg, endocrinologist, ophthalmologist) is recommended for the management of select adverse events and ongoing management of patients on immunotherapy, as needed. In clinical trials, at the discretion of the treating physician, treatment with immunotherapy was typically reinitiated once the adverse event had been successfully managed.Citation12,Citation75,Citation87

Role of the advanced practice registered nurse

It is essential to educate all members of the health care team regarding the introduction of new treatment regimens. The advance practice nurse is involved in the coordination of these education efforts. In our center, education sessions for physicians, advanced practice registered nurses, research nurses, and pharmacists are scheduled prior to the initiation of all new clinical trials to provide indepth education regarding the new therapy. Symptom management algorithms are reviewed during the new therapy planning sessions. Thereafter, the team works closely with the nursing leadership to provide education for the nursing staff, including the importance of frequent symptom monitoring. The advanced practice registered nurse is ideally placed to monitor the patient for physical side effects and to order appropriate diagnostic evaluations for suspected select adverse events. The advanced practice registered nurse is also involved in coordinating the consult services needed for the management of select adverse events.

The successful treatment of patients on immunotherapy depends on the diligence of ongoing assessment/identification and management of immune-mediated side effects. Unmanaged select adverse events can mean the discontinuation of potentially beneficial therapy, and in some cases, can be fatal.

Conclusion

Immunotherapies represent a novel approach to the treatment of NSCLC, and offer the potential for extended benefits, even in advanced disease. Unlike targeted agents, the efficacy of immunotherapy is not limited to patients with particular mutations, and may have broad applicability. As immunotherapies have novel antitumor effects, such as pseudoprogression, repeat biopsies and/or confirmatory scans may be necessary to inform treatment decisions. Also, unlike chemotherapy or targeted therapy, health care providers need to consider select adverse events for patients receiving immunotherapy. Although select adverse events may not be a familiar concept in oncology clinics, most select adverse events can be managed with awareness and action, and immunotherapy may be maintained or reinitiated following resolution of immune-related adverse events. To ensure that these therapies can be used to their fullest benefit, health care providers should be aware of the unique response patterns and immune-mediated side effects of these agents so that they can make appropriate treatment decisions. Nurses will play a key role as immunotherapies become more common in the clinic, both in treating patients and in the education of patients, family members, and other health care providers.

Disclosure

The author takes full responsibility for the content of this publication and confirms that it reflects her viewpoint and medical expertise. The author also wishes to acknowledge StemScientific, funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb, for writing and editorial support. Neither Bristol-Myers Squibb nor StemScientific influenced the content of the manuscript, nor did the author receive financial compensation for authoring the manuscript.

References

- American Cancer SocietyCancer facts and figures 2013 Available from: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2013/index Updated 2013Accessed October 8, 2013

- MolinaJRYangPCassiviSDSchildSEAdjeiAANon-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorshipMayo Clin Proc200883558459418452692

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®)Non-small cell lung cancer Version 22013 Available from: http://www.nccn.com. Updated 2013Accessed October 8, 2013

- JännePAEngelmanJAJohnsonBEEpidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: implications for treatment and tumor biologyJ Clin Oncol200523143227323415886310

- CepedaVFuertesMACastillaJAlonsoCQuevedoCPérezJMBiochemical mechanisms of cisplatin cytotoxicityAnticancer Agents Med Chem20077131817266502

- KwakELBangYJCamidgeDRAnaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancerN Engl J Med2010363181693170320979469

- PaezJGJännePALeeJCEGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapyScience200430456761497150015118125

- ShigematsuHLinLTakahashiTClinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancersJ Natl Cancer Inst200597533934615741570

- ThunnissenEBubendorfLDietelMEML4-ALK testing in non-small cell carcinomas of the lung: a review with recommendationsVirchows Arch2012461324525722825000

- GarbeCEigentlerTKKeilholzUHauschildAKirkwoodJMSystematic review of medical treatment in melanoma: current status and future prospectsOncologist201116152421212434

- PardollDMThe blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapyNat Rev Cancer201212425226422437870

- TopalianSLHodiFSBrahmerJRSafety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancerN Engl J Med2012366262443245422658127

- WolchokJDKlugerHCallahanMKNivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanomaN Engl J Med2013369212213323724867

- WolchokJDNeynsBLinetteGIpilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging studyLancet Oncol201011215516420004617

- SchreiberRDOldLJSmythMJCancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotionScience201133160241565157021436444

- GrulichAEvan LeeuwenMTFalsterMOVajdicCMIncidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysisLancet20073709581596717617273

- FifeBTBluestoneJAControl of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathwaysImmunol Rev200822416618218759926

- BabaTHanagiriTIchikiYLack and restoration of sensitivity of lung cancer cells to cellular attack with special reference to expression of human leukocyte antigen class I and/or major histocompatibility complex class I chain related molecules A/BCancer Sci200798111795180217725806

- FukuyamaTIchikiYYamadaSCytokine production of lung cancer cell lines: Correlation between their production and the inflammatory/ immunological responses both in vivo and in vitroCancer Sci20079871048105417511773

- JadusMRNatividadJMaiALung cancer: a classic example of tumor escape and progression while providing opportunities for immunological interventionClin Dev Immunol2012201216072422899945

- NiehansGABrunnerTFrizelleSPHuman lung carcinomas express Fas ligandCancer Res1997576100710129067260

- PetersenRPCampaMJSperlazzaJTumor infiltrating Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells are associated with recurrence in pathologic stage I NSCLC patientsCancer2006107122866287217099880

- ShimizuKNakataMHiramiYYukawaTMaedaATanemotoKTumor-infiltrating Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are correlated with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and are associated with recurrence in resected non-small cell lung cancerJ Thorac Oncol20105558559020234320

- Yervoy®(ipilimumab) [package insert]Princeton, NJ, USABristol-Myers Squibb Company2013

- HodiFSO’DaySJMcDermottDFImproved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanomaN Engl J Med2010363871172320525992

- Provenge®(ipilimumab) [package insert]Seattle, WA, USADendreon Corporation2011

- KantoffPWHiganoCSShoreNDSipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancerN Engl J Med2010363541142220818862

- Al-ShibliKIDonnemTAl-SaadSPerssonMBremnesRMBusundLTPrognostic effect of epithelial and stromal lymphocyte infiltration in non-small cell lung cancerClin Cancer Res200814165220522718698040

- Dieu-NosjeanMCAntoineMDanelCLong-term survival for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with intratumoral lymphoid structuresJ Clin Oncol200826274410441718802153

- HiraokaKMiyamotoMChoYConcurrent infiltration by CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells is a favourable prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung carcinomaBr J Cancer200694227528016421594

- ZhuangXXiaXWangCA high number of CD8+ T cells infiltrated in NSCLC tissues is associated with a favorable prognosisAppl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol2010181242819713832

- TakanamiITakeuchiKGigaMThe prognostic value of natural killer cell infiltration in resected pulmonary adenocarcinomaJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg200112161058106311385371

- VillegasFRCocaSVillarrubiaVGPrognostic significance of tumor infiltrating natural killer cells subset CD57 in patients with squamous cell lung cancerLung Cancer2002351232811750709

- DasanuCASethiNAhmedNImmune alterations and emerging immunotherapeutic approaches in lung cancerExpert Opin Biol Ther201212792393722559147

- PlatonovaSCherfils-ViciniJDamotteDProfound coordinated alterations of intratumoral natural killer cell phenotype and function in lung carcinomaCancer Res201171165412542221708957

- SchneiderTHoffmannHDienemannHNon-small cell lung cancer induces an immunosuppressive phenotype of dendritic cells in tumor microenvironment by upregulating B7-H3J Thorac Oncol2011671162116821597388

- SchneiderTKimpflerSWarthAFoxp3(+) regulatory T cells and natural killer cells distinctly infiltrate primary tumors and draining lymph nodes in pulmonary adenocarcinomaJ Thorac Oncol20116343243821258248

- WangRLuMZhangJIncreased IL-10 mRNA expression in tumor-associated macrophage correlated with late stage of lung cancerJ Exp Clin Cancer Res2011306221595995

- ZeniEMazzettiLMiottoDMacrophage expression of interleukin-10 is a prognostic factor in nonsmall cell lung cancerEur Respir J200730462763217537769

- HannaNShepherdFAFossellaFVRandomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapyJ Clin Oncol20042291589159715117980

- Lyseng-WilliamsonKAFentonCDocetaxel: a review of its use in metastatic breast cancerDrugs200565172513253116296875

- Xalkori®(crizotinib) [package insert]New York, NY, USAPfizer2013

- PallisAGFennellDASzutowiczELeighlNBGreillierLDziadziuszkoRBiomarkers of clinical benefit for anti-epidermal growth factor receptor agents in patients with non-small-cell lung cancerBr J Cancer201110511821654681

- ShepherdFARodriguesPJCiuleanuTErlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancerN Engl J Med2005353212313216014882

- BangYJThe potential for crizotinib in non-small cell lung cancer: a perspective reviewTher Adv Med Oncol20113627929122084642

- SandlerAGrayRPerryMCPaclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancerN Engl J Med2006355242542255017167137

- SienelWVarwerkCLinderAMelanoma associated antigen (MAGE)-A3 expression in Stages I and II non-small cell lung cancer: results of a multi-center studyEur J Cardiothorac Surg200425113113414690745

- VansteenkisteJFZielinskiMLinderAAdjuvant MAGE-A3 immunotherapy in resected non-small-cell lung cancer: phase II randomized study resultsJ Clin Oncol201343 Abstr 7103

- GlaxoSmithKlineGSK1572932A Antigen-Specific Cancer Immunotherapeutic as Adjuvant Therapy in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00480025. NLM identifier NCT00480025Accessed December 11, 2013

- ReckMVansteenkisteJBrahmerJRTargeting the immune system for management of NSCLC: the revival?Curr Respir Care Rep2013212239

- ButtsCMurrayNMaksymiukARandomized phase IIB trial of BLP25 liposome vaccine in stage IIIB and IV non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200523276674668116170175

- EMDSeronoCancer Vaccine Study for Unresectable Stage III Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (START) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00409188 NLM identifier: NCT00409188Accessed December 11, 2013

- Merck KGaACancer Vaccine Study for Stage III, Unresectable, Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) in the Asian Population (INSPIRE) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01015443 NLM identifier: NCT01015443Accessed December 11, 2013

- QuoixERamlauRWesteelVTherapeutic vaccination with TG4010 and first-line chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a controlled phase 2B trialLancet Oncol201112121125113322019520

- TransgenePhase IIB/III of TG4010 Immunotherapy In Patients With Stage IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (TIME) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01383148 NLM identifier: NCT01383148Accessed December 11, 2013

- NemunaitisJDillmanROSchwarzenbergerPOPhase II study of belagenpumatucel-L, a transforming growth factor beta-2 antisense gene-modified allogeneic tumor cell vaccine in non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200624294721473016966690

- NovaRx CorporationPhase III Lucanix™ Vaccine Therapy in Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Following Front-line Chemotherapy (STOP) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00676507 NLM identifier: NCT00676507Accessed December 11, 2013

- Neninger VinagerasEde la TorreAOsorio RodríguezMPhase II randomized controlled trial of an epidermal growth factor vaccine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol20082691452145818349395

- Bioven EuropeA Randomized Trial to Study the Safety and Efficacy of EGF Cancer Vaccination in Late-stage (IIIB/IV) Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Patients (NSCLC) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01444118 NLM identifier: NCT01444118Accessed December 11, 2013

- MargolinKAWongSLPenrodJREffectiveness and safety of first-line ipilimumab 3 mg/kg therapy for advanced melanoma: evidence from a US multisite retrospective chart reviewPoster 3742 presented at the European Cancer CongressSeptember 27 to October 1, 2013Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- PattDJudayTPenrodJRChenCWongSLA community-based, real-world, study of treatment-naïve advanced melanoma (AM) patients treated with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab (IPI) in the United StatesPoster 3751 presented at the European Cancer CongressSeptember 27 to October 1, 2013Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- LynchTJBondarenkoILuftAIpilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II studyJ Clin Oncol201230172046205422547592

- Bristol-Myers SquibbTrial in Squamous Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Subjects Comparing Ipilimumab Plus Paclitaxel and Carboplatin Versus Placebo Plus Paclitaxel and Carboplatin Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01285609 NLM identifier: NCT01285609Accessed December 11, 2013

- HamidOCarvajalRDAnti-programmed death-1 and anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibodies in cancer therapyExpert Opin Biol Ther201313684786123421934

- BrahmerJRHornLAntoniaSJNivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): overall survival and long-term safety in a phase 1 trialAbstract MO18.03 presented at the 15th International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer World Conference on Lung CancerOctober 27–30, 2013Sydney, Australia

- Bristol-Myers SquibbStudy of BMS-936558 (Nivolumab) Compared to Docetaxel in Previously Treated Advanced or Metastatic Squamous Cell Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) (CheckMate 017) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01642004 NLM identifier: NCT01642004Accessed December 11, 2013

- Bristol-Myers SquibbStudy of BMS-936558 (Nivolumab) Compared to Docetaxel in Previously Treated Metastatic Non-squamous NSCLC (CheckMate 057) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01673867 NLM identifier: NCT01673867Accessed December 11, 2013

- Bristol-Myers SquibbStudy of Nivolumab (BMS-936558) in Subjects With Advanced or Metastatic Squamous Cell Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Who Have Received At Least Two Prior Systemic Regimens (CheckMate 063) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01721759 NLM identifier: NCT01721759Accessed December 11, 2013

- Bristol-Myers SquibbA Phase 1/2, Open-label Study of Nivolumab Monotherapy or Nivolumab Combined With Ipilimumab in Subjects With Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01928394 NLM identifier: NCT01928394Accessed December 11, 2013

- Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer CenterPhase II Anti-PD1 Epigenetic Priming Study in NSCLC. (NA_00084192) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01928576 NLM identifier: NCT01928576Accessed December 11, 2013

- Bristol-Myers SquibbStudy of Nivolumab (BMS-936558) in Combination With Gemcitabine/Cisplatin, Pemetrexed/Cisplatin, Carboplatin/ Paclitaxel, Bevacizumab Maintenance, Erlotinib, Ipilimumab or as Monotherapy in Subjects With Stage IIIB/IV Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) (CheckMate 012) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01454102 NLM identifier: NCT01454102Accessed December 11, 2013

- HamidORobertCDaudASafety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanomaN Engl J Med2013369213414423724846

- GaronEBBalmanoukianAHamidOPreliminary clinical safety and activity of MK-3475 monotherapy for the treatment of previously treated patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)Abstract MO18.02 presented at the 15th International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer World Conference on Lung CancerOctober 27–30, 2013Sydney, Australia

- MerckStudy of Two Doses of MK-3475 Versus Docetaxel in Previously-Treated Participants With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (MK-3475-010) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01905657 NLM identifier: NCT01905657Accessed December 11, 2013

- BrahmerJRTykodiSSChowLQSafety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancerN Engl J Med2012366262455246522658128

- HornLHerbstRSSpigelDRAn analysis of the relationship of clinical activity to baseline EGFR status, PD-L1 expression and prior treatment history in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) following PD-L1 blockade with MPDL3280A (anti-PDL1)Abstract MO18.01 presented at the 15th International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer World Conference on Lung CancerOctober 27–30, 2013Sydney, Australia

- GenentechA Study Of MPDL3280A in Patients With PD-L1-Positive Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01846416 NLM identifier: NCT01846416Accessed December 11, 2013

- Hoffmann-La RocheA Study of MPDL3280A Compared With Docetaxel in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer After Platinum Failure Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01903993 NLM identifier: NCT01903993Accessed December 11, 2013

- Bristol-Myers SquibbStudy of Nivolumab (BMS-936558) in Combination With Gemcitabine/Cisplatin, Pemetrexed/Cisplatin, Carboplatin/ Paclitaxel, Bevacizumab Maintenance, Erlotinib, Ipilimumab or as Monotherapy in Subjects With Stage IIIB/IV Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) (CheckMate 012) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01454102 NLM identifier: NCT01454102Accessed December 11, 2013

- Bristol-Myers SquibbSafety Study of IL-21/Anti-PD-1 Combination in the Treatment of Solid Tumors Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01629758 NLM identifier: NCT01629758Accessed December 11, 2013

- Bristol-Myers SquibbA Phase I Study of an Anti-KIR Antibody in Combination With an Anti-PD1 Antibody in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01714739 NLM identifier: NCT01714739Accessed December 11, 2013

- ClinicalTrialsgov [homepage on the Internet]US National Institutes of Health Updated 2013 Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/Accessed October 8, 2013

- WolchokJDHoosAO’DaySGuidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteriaClin Cancer Res200915237412742019934295

- PrietoPAYangJCSherryRMCTLA-4 blockade with ipilimumab: long-term follow-up of 177 patients with metastatic melanomaClin Cancer Res20121872039204722271879

- HerbstRSGordonMSFineGDA study of MPDL3280A, an engineered PD-L1 antibody in patients with locally advanced or metastatic tumorsJ Clin Oncol201331Suppl Abstr 3000

- WeberJSKählerKCHauschildAManagement of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumabJ Clin Oncol201230212691269722614989

- WeberJReview: anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab: case studies of clinical response and immune-related adverse eventsOncologist200712786487217673617