Abstract

Background

Patients with COPD might not report mild exacerbation. The frequency, risk factors, and impact of mild exacerbation on COPD status are unknown.

Objectives

The present study was performed to compare features between mild exacerbation and moderate or severe exacerbation in Japanese patients with COPD.

Patients and methods

An observational COPD cohort was designed at Keio University and affiliated hospitals to prospectively investigate the management of COPD comorbidities. This study analyzes data only from patients with COPD who had completed annual examinations and questionnaires over a period of 2 years (n=311).

Results

Among 59 patients with mild exacerbations during the first year, 32.2% also experienced only mild exacerbations in the second year. Among 60 patients with moderate or severe exacerbations during the first year, 40% also had the same severity of exacerbation during the second year. Findings of the COPD assessment test and the symptom component of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire at steady state were worse in patients with mild exacerbations than in those who were exacerbation free during the 2-year study period, although the severity of the ratio of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second did not differ between them. Severe airflow limitation (the ratio of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second <50%) and experience of mild exacerbations independently advanced the likelihood of an elevated COPD assessment test score to ≥2 per year.

Conclusion

The severity of COPD exacerbation seemed to be temporally stable over 2 years, and even mild exacerbations adversely impacted the health-related quality of life of patients with COPD.

Introduction

COPD is characterized by progressive and partially reversible airflow limitation, and it is among the leading causes of death worldwide.Citation1 The disease is complicated by exacerbation, which is associated with a poor prognosis,Citation2,Citation3 and places a considerable economic burden on health services and society.Citation4,Citation5 It has also been recognized that some patients with COPD are particularly prone to exacerbations, and these patients have been termed “frequent exacerbators”.Citation6,Citation7 Exacerbations are categorized into mild, moderate, and severe ones in terms of either clinical presentation (number of symptoms) or utilization of health care resources.Citation8–Citation10 Most of the published studies have surveyed moderate-to-severe exacerbation that required a change in regular medication or hospital admission.Citation2,Citation3,Citation11 However, one observational study found that about half of all exacerbations remain unreported, yet the recovery periods are similar to those of moderate or severe exacerbations.Citation12 Other studies have also shown that unreported exacerbations might negatively affect the health-related quality of life (QOL) of patientsCitation13,Citation14 and underline the importance of early detection of exacerbations and appropriate therapy.

The reported frequency of moderate or severe exacerbation is low among Japanese patients with COPD,Citation15–Citation17 and lower than that in other countries.Citation7 However, the frequency, risk factors, and impact of mild exacerbation on COPD status in a Japanese population of patients with COPD have not yet been clarified. We have been conducting a multicenter, observational cohort study to longitudinally examine the comorbidities of COPD in Japan, called the Keio COPD Comorbidity Research (K-CCR). We recently reported the findings of cross-sectional studies at enrollment showing associations between comorbidities and various aspects of COPD.Citation18–Citation20 Here, we aimed to compare the impact on the health-related QOL and pulmonary function between mild exacerbation and moderate or severe exacerbation in Japanese patients with COPD. The reported longitudinal changes in St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) categories and their determinants are markedly different between its categories.Citation21 Therefore, we hypothesized that such differences would be more markedly seen when patients were classified based on the severity of exacerbation. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with COPD to detect the severity of all exacerbation events and applied a robust definition of exacerbation based on symptomatic and treatment criteria.

Patients and methods

Study populations

An observational cohort study has been established at Keio University and affiliated hospitals to prospectively determine the optimal management of COPD comorbidities and register the findings with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN000003470). We enrolled 572 patients between April 2010 and December 2012, including those who had been diagnosed with COPD by pulmonary physicians and those referred for the assessment of possible COPD based on symptoms and/or presence of emphysematous changes on computed tomography (CT) images as described.Citation18,Citation19 We analyzed only data from patients who had COPD confirmed by spirometry, had completed annual examinations and questionnaires, and had visited outpatient clinics at the participating hospitals monthly or bimonthly for regular clinical checkups for 2 years (n=311). The ethics committees of Keio University and affiliated hospitals approved the study protocol, and each patient provided written informed consent to analyze and present their data. The study conforms in all respects to the Declaration of Helsinki adopted by the 59th WMA General Assembly, Seoul, Korea, October 2008.

Assessment of exacerbation

Doctors assessed whether COPD symptoms had worsened since the last assessment and required treatment during scheduled appointments or emergency presentation. Symptoms constituting an exacerbation were identified based on strict criteria adapted from the original definition of previous reports.Citation10,Citation22 Independent investigators in the present study retrospectively judged number and severity of exacerbations from reviews of physicians’ medical records. Mild COPD exacerbation was defined as worsening of symptoms that were self-managed (by measures such as an increase in salbutamol use) and resolved without systemic corticosteroids or antibiotics. Moderate COPD exacerbation was defined as a requirement for treatment with systemic corticosteroids or antibiotics or both. Severe COPD exacerbation was defined as hospitalization, including an emergency admission for >24 hours.

Assessment of clinical parameters and comorbidities

All patients were clinically stable and without exacerbations for at least 1 month before study enrollment and the day of annual examinations. All questionnaires of health status, including all categories of SGRQCitation23–Citation25 and the COPD assessment test (CAT),Citation26,Citation27 were completed at home while the disease was stable at baseline and then annually thereafter. All patients were also assessed by spirometry and CT imaging. The extent of emphysema was quantified as the ratio of low attenuation area (LAA%)Citation28 and the ratio of airway wall area (WA%)Citation29 on CT images using custom-made software (AZE Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).Citation19 Images of a Multipurpose Chest Phantom N1 (Kyoto Kagaku, Kyoto, Japan) were acquired at the start of the study to calibrate CT instrument from various manufacturers, which also enabled the assessment of longitudinal changes in LAA%.Citation19 Comorbid diagnoses were established using clinical history and examination findings based on a review of available medical records as reported previously.Citation18,Citation19 Ophthalmological examinations were performed to estimate the prevalence of cataract.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD or as median ± interquartile range. Data were compared between two groups using t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, and χ2 test and among three groups using analysis of variance and the Tukey–Kramer, Kruskal–Wallis, and χ2 tests. The effects of factors on minimal clinical important changes in CAT (ΔCAT ≥2 per year) were assessed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.Citation30 Differences in levels of CAT, SGRQ, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), LAA%, and in rates of change over time among three groups classified according to the severity of exacerbation were estimated using mixed-effects modelingCitation31 with Bonferroni correction. Two-sided P-values of <0.05 were considered significant for all tests. Data were analyzed using the JMP 10 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The mixed-effect model was applied using SPSS 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Frequency of various severities of exacerbations

shows the baseline characteristics of the study participants. The proportions of patients without exacerbation, with only mild exacerbations, and with moderate or severe exacerbations during the first and second years of follow-up were similar (61.7%, 19.0%, and 19.3% vs 68.2%, 14.5%, and 17.4%, respectively, P=0.2029). The frequency of moderate or severe exacerbation during follow-up (events per person per year) was 0.28. Only seven patients, comprising three patients in GOLD stage II, three patients in GOLD stage III, and one patient in GOLD stage IV, had more than two moderate or severe exacerbations per year.

Table 1 Characteristics of study population

Temporal stability of exacerbation severity during follow-up

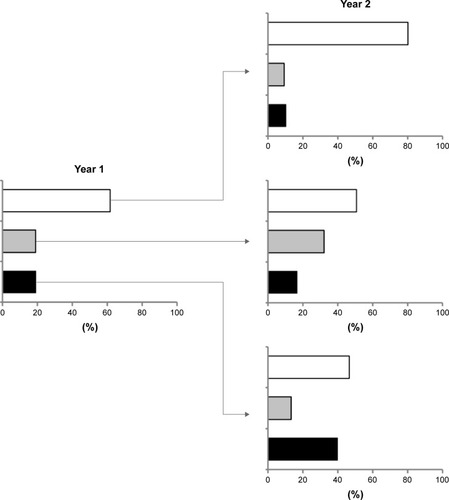

Among 59 patients with mild exacerbations during the first year of follow-up, 19 (32.2%) patients also experienced only mild exacerbations during the second year, and among 60 patients with moderate or severe exacerbations during the same period, 24 (40.0%) patients also experienced the same severity of exacerbations during the second year ().

Figure 1 Frequency of exacerbation with different severities over 2 years.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients grouped according to the severity of exacerbations

We compared the characteristics among three groups of patients to determine the impact of exacerbation severity on COPD status during 2 years of follow-up. Patients were grouped according to whether they were exacerbation free (n=154), had only mild exacerbation (mild exacerbator, n=67), or had at least one moderate or severe exacerbation (moderate/severe exacerbator; n=90). shows the baseline characteristics of these groups. The ratio of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (%FEV1) was significantly lower, and the LAA% was higher in the moderate/severe exacerbator compared with the mild exacerbator and exacerbation-free groups at baseline (%FEV1: 53.3 vs 65.4 and 67.4, P=0.0006 and P<0.0001, respectively; LAA%: 20.3 vs 9.0 and 10.6, P=0.0013 and P=0.0004, respectively).

Table 2 Comparison of baseline characteristics among patients stratified according to severity of exacerbation

Comparison of comorbidities according to the severity of exacerbations

shows that the frequency of some comorbidities differed among the exacerbation-free, mild exacerbator, and moderate/severe exacerbator groups. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was higher in the mild exacerbator group than in the exacerbation-free group (46.2% vs 30.4%, P=0.0281). In contrast, the prevalence of anemia, cataracts, and prostatic hypertrophy was higher in the moderate/severe exacerbator group than in the exacerbation-free group (anemia: 29.7% vs 17.5%, P=0.0286; cataract: 63.6% vs 40.4%, P=0.0044; prostatic hypertrophy: 20.7% vs 8.7%, P=0.0100). The frequency of cardiovascular disease and depression did not significantly differ among the three groups.

Table 3 Comparison of baseline comorbidities among patients stratified according to severity of exacerbation

Relationship of exacerbations with FEV1 and LAA% during 2 years of follow-up

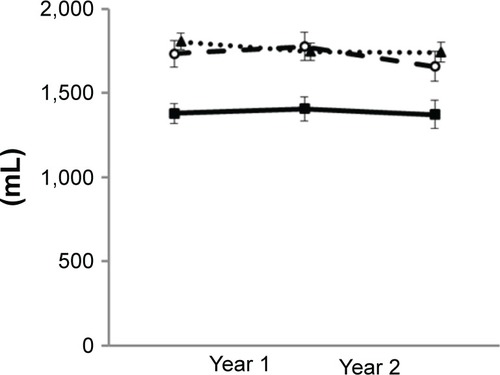

The FEV1 was significantly lower in the moderate/severe exacerbator group than in the mild exacerbator and exacerbation-free groups during follow-up (P=0.001 and P<0.001, respectively) but did not differ between the mild exacerbator and exacerbation-free groups (P=1.000; ). The rate of change in FEV1 did not differ among the three groups during follow-up (P=0.5446).

Figure 2 Annual changes in FEV1 in three groups of patients over 2 years of follow-up.

Abbreviation: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

We analyzed only data from patients who underwent annual CT assessment more than twice and provided comparable quantitative LAA% data to determine annual changes in LAA% (n=179). The values for LAA% and rates of change in LAA% did not significantly differ among the three groups during 2 years of follow-up (P=0.0887 and P=0.3013, respectively; ).

Figure 3 Annual changes in LAA% in three groups of patients over 2 years of follow-up.

Abbreviation: LAA%, ratio of low attenuation area.

Relationships between exacerbations and CAT and SGRQ scores during follow-up

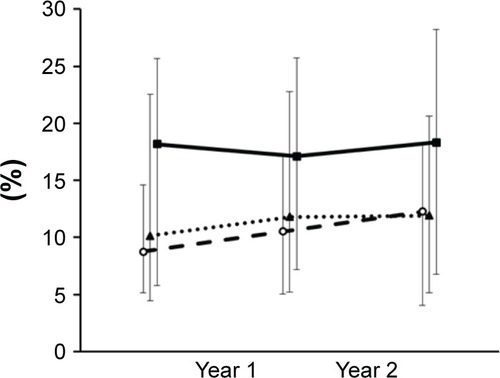

Not only did the moderate/severe exacerbator group significantly differ in total CAT scores during 2 years of follow-up compared with the exacerbation-free group (P<0.001), but the mild exacerbator group also exhibited significant difference compared with the exacerbation-free group (P=0.014). There was no difference between mild and moderate/severe exacerbator groups (). The moderate/severe exacerbator group included seven patients who experienced more than two moderate or severe exacerbations during each year, and their CAT scores at baseline were 16.5 (interquartile range, 5.75–28.75). Among the eight items comprising CAT scores, a significant difference persisted in the respiratory symptom components of cough, sputum, and dyspnea and their activity (P=0.0002, P=0.0006, P<0.0001, and P=0.0045, respectively). We assessed the effect of mild exacerbation on CAT scores using multivariate logistic regression analysis that included risk factors that either reached significance or trended toward an association on univariate analysis. Severe airflow limitation (%FEV1 <50%) and mild exacerbation independently advanced the likelihood of ΔCAT ≥2 per year (P=0.042 and P=0.028, respectively; ).

Table 4 Predictors of CAT (minimal clinical important difference; ΔCAT ≥2 per year) increase determined by multivariate logistic regression analysis

Figure 4 Annual changes in CAT scores in three groups of patients over 2 years of follow-up.

Abbreviation: CAT, COPD assessment test.

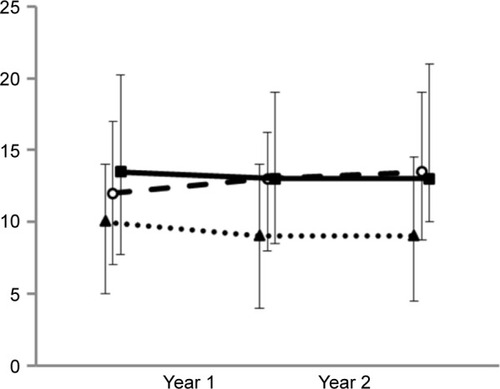

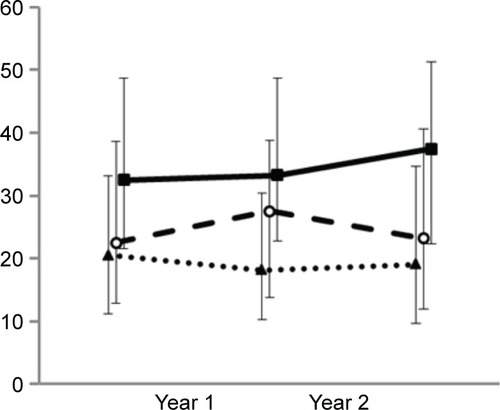

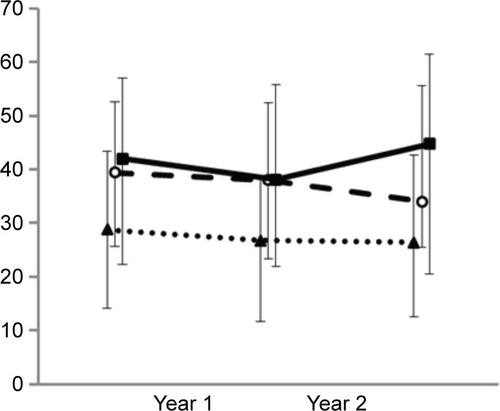

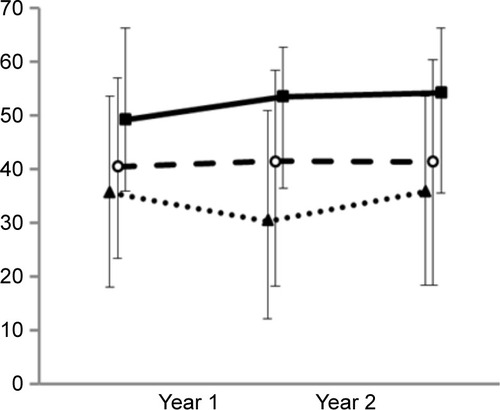

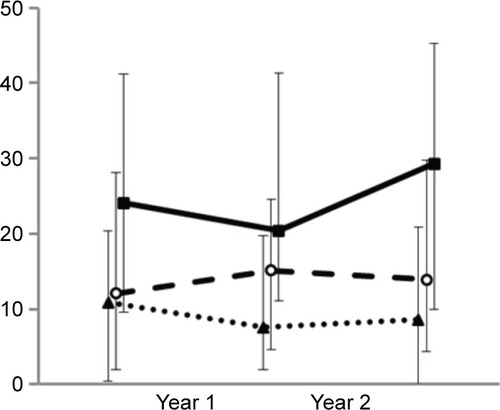

The 2-year follow-up also revealed a significant difference in all categories of SGRQ scores between moderate/severe exacerbator groups and exacerbation-free groups (total, P<0.001, ; symptoms; P<0.001, ; activity, P<0.001, ; impact, P<0.001, ). However, the mild exacerbator group exhibited significant difference compared with the exacerbation-free group only in total score and symptoms category of SGRQ (total, P=0.041, ; symptoms; P=0.002, ; activity, P=0.226, ; impact, P=0.064, ).

Figure 5 Annual changes in SGRQ total scores over 2 years of follow-up.

Notes: Patients in the exacerbation-free (••▲••), mild exacerbator (–○–), and moderate/severe exacerbator (–■–) groups. Moderate/severe exacerbator vs exacerbation free, P<0.001; mild exacerbator vs exacerbation free, P=0.041; and mild exacerbator vs moderate/severe exacerbator, P=0.013.

Abbreviation: SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Figure 6 Annual changes in SGRQ symptoms category over 2 years of follow-up.

Notes: Patients in the exacerbation-free (••▲••), mild exacerbator (–○–), and moderate/severe exacerbator (–■–) groups. Moderate/severe exacerbator vs exacerbation free, P<0.001; mild exacerbator vs exacerbation free, P=0.002; and mild exacerbator vs moderate/severe exacerbator, P=1.000.

Abbreviation: SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Figure 7 Annual changes in SGRQ activity category over 2 years of follow-up.

Notes: Patients in the exacerbation-free (••▲••), mild exacerbator (–○–), and moderate/severe exacerbator (–■–) groups. Moderate/severe exacerbator vs exacerbation free, P<0.001; mild exacerbator vs exacerbation free, P=0.226; and mild exacerbator vs moderate/severe exacerbator, P=0.004.

Abbreviation: SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Figure 8 Annual changes in SGRQ impact category over 2 years of follow-up.

Abbreviation: SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that patients with moderate or severe exacerbations have a rapid decline in lung functionCitation32,Citation33 and emphysema progression,Citation16 an inferior health-related QOL,Citation11 and decreased exercise performance.Citation34 However, the influence of mild exacerbation on QOL, lung function, and emphysema has remained unclear. This study shows that steady-state CAT scores and the symptom component of SGRQ remained worse in the mild exacerbator group than in the exacerbation-free group during 2 years of follow-up, although the severity of FEV1 did not significantly differ. However, mild exacerbations did not change the levels of activity or impact scores of SGRQ at steady state. The CAT and other SGRQ scores also remained worse in the moderate/severe exacerbator compared with the exacerbation-free group during 2 years of follow-up, but they were concomitant with a lower FEV1.

The unique point of this study was the focus on mild exacerbation. To ascertain, “mild” exacerbation is limited because perception of the actual symptoms is subjective. Many studies have tried to establish standardized methods, but some issues have arisen.Citation35,Citation36 Independent investigators in this study selected most of the patients with mild COPD exacerbation from detailed retrospective reviews of individual clinical records, in which patients reported issues such as having had a common cold since the last consultation with a respiratory physician. The physicians then assumed that the health status of the patient had been restored to normal without intervention with antibiotics and/or steroid. Sometimes, COPD exacerbation was objectively judged during an unscheduled primary care assessment or when a patient walked into an emergency center. Reliability depends on self-reported previous illness that patients need to recall over various periods. The investigators were aware of the limitation that the frequency of mild exacerbations might be underestimated because patients might forget episodes if they were very mild or very frequent or when they recognized that reporting was not needed. On the other hand, the risk of overestimating exacerbation severity must be minimal because patients report it after understanding the consequences of recovery from such episodes compared with the patient diary approach.Citation14,Citation22

One of the major strengths of this study is the comprehensive assessment of comorbid factors in the K-CCR cohort study, which has been characterized in detail. Generally, it was reported that comorbidities of conditions, such as cardiac disease,Citation37,Citation38 GERD,Citation39,Citation40 and depressionCitation41 are associated with moderate or severe exacerbations. However, the frequency of these comorbidities did not significantly differ between moderate/severe exacerbator and exacerbation-free groups in the present study, which could be explained as follows. Japanese patients with COPD have different characteristics, such as more advanced age, lower BMI, emphysema-dominant type,Citation15,Citation42 and a different profile of comorbidities, compared with non-Japanese, as well as a lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome and a higher frequency of osteoporosis and malnutrition.Citation18,Citation43 This study finds that symptoms of GERD are associated with mild exacerbations but not with moderate or severe exacerbations. Thus, GERD might cause mild exacerbations or comorbid GERD could worsen CAT and SGRQ scores. Whether or not treatment for GERD contributes to improve these scores in patients with mild exacerbations or decrease the frequency of mild exacerbations should be worth investigating. Interactions between host factors, bacteria, viruses, and air pollution are thought to exacerbate COPD.Citation44 Human rhinovirus prevalence and load increased at COPD exacerbation and resolved during recovery.Citation45 The etiology might be associated with differences in exacerbation severity.

Our cohort study showed that the current frequency of moderate or severe exacerbations of COPD is as low as that found in previous studies of Japanese patients with COPDCitation15–Citation17 and lower than that found in other countriesCitation7 and in some recent clinical trials.Citation46,Citation47 This discrepancy could be explained as follows. This study includes patients with mild airflow limitation (GOLD 1, 22.2%), unlike previous clinical studies that did not recruit such patients. Our patients were mostly past smokers (87.5%) and were regularly treated with bronchodilators (72.3%). Although the reasons for the difference in exacerbation frequency remain to be defined, the difference in the low rate of exacerbation might not be unique to Japan, and they might have important implications for clinical trials of exacerbation.

This study is limited by the short observational period of only 2 years, and the fact that QOL scores, lung function, and chest CT images were only monitored annually. A longer follow-up with more frequent measures is required to develop a more thorough understanding of the long-term impact of mild exacerbation on the progression of clinical parameters. Large clinical trials of patients with COPD have shown that current treatments have significantly reduced moderate or severe exacerbationsCitation46,Citation47 and early intervention also improves outcomes of exacerbations.Citation13,Citation48 However, the effectiveness of such treatments on mild exacerbations remains unknown.

Conclusion

Even mild exacerbations adversely impacted the health-related QOL of patients with COPD. Appropriate intervention for mild exacerbations, as well as moderate or severe ones, would be important for improving outcomes for patients with COPD.

Author contributions

Minako Sato and Shotaro Chubachi contributed to the study design, analyzed the data, and wrote the article. Mamoru Sasaki, Mizuha Haraguchi, Naofumi Kameyama, Akihiro Tsutsumi, and Saeko Takahashi contributed to patient enrollment and acquisition of their clinical information. Hidetoshi Nakamura and Koichiro Asano were involved in the study design. Tomoko Betsuyaku planned and supervised the study and wrote the article. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Tsuyoshi Sakamoto from AZE Ltd. and Masahiro Jinzaki from the Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Keio University School of Medicine, for helping to analyze chest CT imaging findings and to calibrate the CT instruments and Chiyomi Uemura for helping in collecting the data. The authors acknowledge all the members of the K-CCR group who participated in this study, including Saiseikai Utsunomiya Hospital, Eiju General Hospital, Tokyo Saiseikai Central Hospital, Sano Public Welfare General Hospital, Nihon Kokan Hospital, Saitama Social Insurance Hospital, Kawasaki City Ida Hospital, Saitama City Hospital, Tokyo Medical Center, Tokyo Dental College Ichikawa General Hospital, Tokyo Electric Power Company Hospital, and the International Medical Welfare College Shioya Hospital.

Disclosure

Tomoko Betsuyaku received honoraria/paid expert testimony, and her university received research grants from GlaxoSmithKline. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VestboJHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- Soler-CataluñaJJMartínez-GarcíaMARomán SánchezPSalcedoENavarroMOchandoRSevere acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622

- AlmagroPSorianoJBHerediaJLWorking Group on COPDSpanish Society of Internal MedicineShort- and medium-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation: the CODEX indexChest2014145597298024077342

- de Miguel-DíezJJiménez-GarcíaRCarrasco-GarridoPTrends in hospital admissions for acute exacerbation of COPD in Spain from 2006 to 2010Respir Med2013107571772323421969

- BlasiFCesanaGMantovaniLGThe clinical and economic impact of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cohort of hospitalized patientsPLoS One201496e10122824971791

- WedzichaJABrillSEAllinsonJPDonaldsonGCMechanisms and impact of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBMC Med20131118123945277

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoAEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) InvestigatorsSusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- WedzichaJADecramerMFickerJHAnalysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations with the dual bronchodilator QVA149 compared with glycopyrronium and tiotropium (SPARK): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group studyLancet Respir Med20131319920924429126

- TomiokaRKawayamaTHoshinoT“Frequent exacerbator” is a phenotype of poor prognosis in Japanese patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20161120721626893552

- AnthonisenNRManfredaJWarrenCPHershfieldESHardingGKNelsonNAAntibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med198710621962043492164

- MiravitllesMFerrerMPontAIMPAC Study GroupEffect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 2 year follow up studyThorax200459538739515115864

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCBhowmikAJeffriesDJWedzichaJATime course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200016151608161310806163

- WilkinsonTMDonaldsonGCHurstJRSeemungalTAWedzichaJAEarly therapy improves outcomes of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004169121298130314990395

- LangsetmoLPlattRWErnstPBourbeauJUnderreporting exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a longitudinal cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177439640118048806

- FukuchiYFernandezLKuoHPEfficacy of tiotropium in COPD patients from Asia: a subgroup analysis from the UPLIFT trialRespirology201116582583521539680

- TanabeNMuroSHiraiTImpact of exacerbations on emphysema progression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183121653165921471102

- SuzukiMMakitaHItoYMHokkaido COPD Cohort Study InvestigatorsClinical features and determinants of COPD exacerbation in the Hokkaido COPD cohort studyEur Respir J20144351289129724232696

- MiyazakiMNakamuraHChubachiSKeio COPD Comorbidity Research (K-CCR) GroupAnalysis of comorbid factors that increase the COPD assessment test scoresRespir Res2014151324502760

- ChubachiSNakamuraHSasakiMKeio COPD Comorbidity Research (K-CCR) GroupPolymorphism of LRP5 gene and emphysema severity are associated with osteoporosis in Japanese patients with or at risk for COPDRespirology201520228629525392953

- MiyazakiMNakamuraHTakahashiSKeio COPD Comorbidity Research (K-CCR) GroupThe reasons for triple therapy in stable COPD patients in Japanese clinical practiceInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101053105926082629

- NagaiKMakitaHSuzukiMHokkaido COPD Cohort Study InvestigatorsDifferential changes in quality of life components over 5 years in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20151074575725914531

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCPaulEABestallJCJeffriesDJWedzichaJAEffect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981575 Pt 1141814229603117

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPA self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireAm Rev Respir Dis19921456132113271595997

- HajiroTNishimuraKTsukinoMIkedaAKoyamaHIzumiTComparison of discriminative properties among disease-specific questionnaires for measuring health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981573 Pt 17857909517591

- HajiroTNishimuraKTsukinoMIkedaAKoyamaHIzumiTAnalysis of clinical methods used to evaluate dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981584118511899769280

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD assessment testEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- KwonNAminMHuiDSValidity of the COPD assessment test translated into local languages for Asian patientsChest2013143370371023460156

- CamiciottoliGBigazziFPaolettiMCestelliLLavoriniFPistolesiMPulmonary function and sputum characteristics predict computed tomography phenotype and severity of COPDEur Respir J201342362663523258785

- TanabeNMuroSTanakaSEmphysema distribution and annual changes in pulmonary function in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Res2012133122512922

- KonSSCanavanJLJonesSEMinimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: a prospective analysisLancet Respir Med20142319520324621681

- RaudenbushSWBrykASHierarchical Linear ModelsNewbury Park, NJSage2002

- HalpinDMDecramerMCelliBKestenSLiuDTashkinDPExacerbation frequency and course of COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012765366123055714

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTAPatelISLloyd-OwenSJWilkinsonTMWedzichaJALongitudinal changes in the nature, severity and frequency of COPD exacerbationsEur Respir J200322693193614680081

- PittaFTroostersTProbstVSSpruitMADecramerMGosselinkRPhysical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPDChest2006129353654416537849

- MackayAJDonaldsonGCPatelARSinghRKowlessarBWedzichaJADetection and severity grading of COPD exacerbations using the exacerbations of chronic pulmonary disease tool (EXACT)Eur Respir J201443373574423988767

- TrappenburgJCTouwenIde Weert-van OeneGHDetecting exacerbations using the clinical COPD questionnaireHealth Qual Life Outcomes2010810220846428

- McGarveyLLeeAJRobertsJGruffydd-JonesKMcKnightEHaughneyJCharacterisation of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in COPD patients in a large UK primary care populationRespir Med2015109222823725613107

- BrekkePHOmlandTSmithPSøysethVUnderdiagnosis of myocardial infarction in COPD – cardiac infarction injury score (CIIS) in patients hospitalised for COPD exacerbationRespir Med200810291243124718595681

- TeradaKMuroSSatoSImpact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms on COPD exacerbationThorax2008631195195518535116

- MartinezCHOkajimaYMurraySCOPD Gene InvestigatorsImpact of self-reported gastroesophageal reflux disease in subjects from COPD Gene cohortRespir Res2014156224894541

- XuWColletJPShapiroSIndependent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178991392018755925

- TatsumiKKasaharaYKurosuKRespiratory Failure Research Group in JapanClinical phenotypes of COPD: results of a Japanese epidemiological surveyRespirology20049333133615363004

- TakahashiSBetsuyakuTThe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease comorbidity spectrum in Japan differs from that in western countriesRespir Investig2015536259270

- DaiMYQiaoJPXuYHFeiGHRespiratory infectious phenotypes in acute exacerbation of COPD: an aid to length of stay and COPD Assessment TestInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102257226326527871

- GeorgeSNGarchaDSWedzichaJAHuman rhinovirus infection during naturally occurring COPD exacerbationsEur Respir J2014441879624627537

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBTORCH InvestigatorsSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSUPLIFT Study InvestigatorsA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20083591543155418836213

- GadouryMASchwartzmanKRouleauMChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Axis of the Respiratory Health Network, Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (FRSQ)Self-management reduces both short- and long-term hospitalisation in COPDEur Respir J200526585385716264046