Abstract

Background

Whether the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in patients with COPD can protect from osteoporosis remains undetermined. The aim of this study is to assess the incidence of osteoporosis in patients with COPD with ICS use and without.

Patients and methods

This is a retrospective cohort and population-based study in which we extracted newly diagnosed female patients with COPD between 1997 and 2009 from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (TNHI) database between 1996 and 2011 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 491, 492, 496). The patients with COPD were defined by the presence of two or more diagnostic codes for COPD within 12 months on either inpatient or outpatient service claims submitted to TNHI. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 40 years or if osteoporosis had been diagnosed prior to the diagnosis of COPD and cases of asthma (ICD-9 CM code 493.X) before the index date. These enrolled patients were followed up till 2011, and the incidence of osteoporosis was determined. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was also used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for incidences of lung cancer.

Results

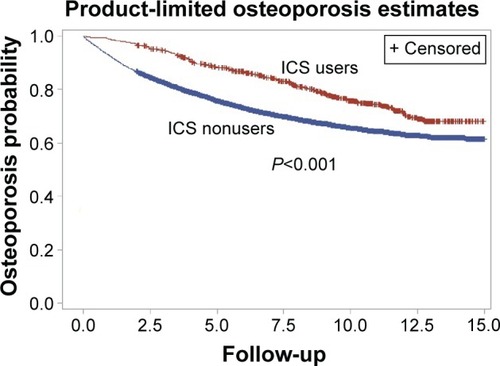

Totally, 10,723 patients with COPD, including ICS users (n=812) and nonusers (n=9,911), were enrolled. The incidence rate of osteoporosis per 100,000 person years is 4,395 in nonusers and 2,709 in ICS users (HR: 0.73, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.63–084). The higher ICS dose is associated with lower risk of osteoporosis (0 mg to ≤20 mg, HR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.69–1.04; >20 mg to ≤60 mg, HR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.59–1.04; and >60 mg, HR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.55–0.96; P for trend =0.0023) after adjusting for age, income, and medications. The cumulative osteoporosis probability significantly decreased among the ICS users when compared with the nonusers (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Female patients with COPD using ICS have a dose–response protective effect for osteoporosis.

Keywords:

Introduction

COPD with persistent airflow limitation is usually progressive and is associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung due to the inhalation of noxious particles or gases.Citation1 Due to persistent low-grade inflammation in systemic circulation and the same risk factors, COPD often coexists with comorbidities.Citation2–Citation7 Osteoporosis is a major comorbidity in COPD associated with poor health status and prognosis.Citation7,Citation8 This risk of comorbid osteoporosis can be increased by low-grade systemic inflammation or the sequelae of COPD, such as poor nutrition, reduced physical activity, and the use of systemic corticosteroids and tobacco smoking. In addition, older age, menopause, and female sex are the other risk factors for osteoporosis.Citation9–Citation11

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are commonly used for the treatment of chronic COPD. In 2014, updated Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines also recommended ICSs in group C and D patients,Citation1 although the long-term safety of ICSs has not been established and the adverse effects of long-term use of systemic glucocorticosteroids are documented as involving loss of bone mineral density.Citation12 The efficacy and side effects of ICSs on bone metabolism in asthma are dependent on the dose and type of corticosteroid,Citation13 but whether this is also found in COPD is undetermined. Long-term treatment with inhaled triamcinolone was associated with increased loss of bone mass in the Lung Health Study II.Citation14 However, this was not seen in the patients with COPD for inhaled budesonide in the EUROSCOP trialCitation15 or for inhaled 500 µg bid (twice per day) fluticasone propionate alone or in combination with salmeterol treatment over a 3-year period in the TORCH trial.Citation16 Two systematic reviews have concluded that long-term ICS use has not been proven to have a significant impact on bone mineral density.Citation17,Citation18 Therefore, to date, this issue of the effect of ICSs on bone metabolism in patients with COPD remains controversial.

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (TNHI) database can provide a larger population and longer follow-up duration than previous studies.Citation13–Citation16 We used this database to conduct a retrospective analysis about the incidence of osteoporosis in patients with COPD with ICS use and without.

Patients and methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital review board (IRB #102-0364B), and the requirement of informed consent was waived due to the fact that personal information had already been deidentified in the National Health Insurance (NHI) Research Database.

Data source

The NHI Program, which provides compulsory universal health insurance, was implemented on March 1, 1995, in Taiwan. Under the NHI, 98% of the island’s population receives all forms of health-care services including outpatient services, inpatient care, Chinese medicine, dental care, childbirth services, physical therapy, preventive health care, home care, and rehabilitation for chronic mental illness. Most medical providers (93%) were under contract with the Bureau of NHI (BNHI), and those not under contract provide fewer health services. More than 96% of the population with insurance coverage through the NHI utilized health services at least one time at contracted medical institutions. From the population of all reimbursement claim records under the single-payer system and using a systematic sampling method, the National Health Research Institute (NHRI) of Taiwan randomly sampled a representative panel database of 1,000,000 subjects in 2,000 designed for research purposes. The NHRI reported that there were no statistically significant differences in the age, sex, and health-care costs between the sample group and all enrollees as noted in our previous report.Citation19

Data in an electronic format on daily clinic visits or hospital admissions can be obtained for each contracted medical institution. For reimbursement, all medical institutions must submit their claims for billable medical services on a standardized electronic format, which includes data elements such as the date of admission and discharge, patient identification number, sex, date of birth, and the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic code for each admission. Therefore, the information from the NHI database appears to be sufficiently complete, reliable, and accurate for use in epidemiological studies.

Design and study participants

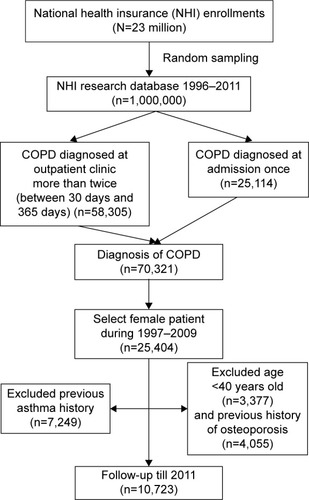

Females are much more likely to develop osteoporosis than males.Citation20 In Taiwan, smoking prevalence is much lower in females when compared with males. The ratio of male to female smoking rates was 10.9:1 among adults (46.8%:4.3%).Citation21 Approximately 15%–20% of these female smokers may develop COPD, thus tobacco consumption confounding the incidence of osteoporosis related to ICSs in Taiwanese females is very limited. Additionally, data about tobacco consumption and second-hand exposure cannot be obtained from our BNHI records. Therefore, to decrease the interference of sex and tobacco exposure in the incidence of osteoporosis, we decided to select only female patients in this study. For the cohort, we identified an exposed study cohort from the database consisting of newly diagnosed female patients with COPD (n=25,404, ICD-9-CM 491, 492, 496) from 1996 to 2011. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 40 years or if osteoporosis had been diagnosed prior to the diagnosis of COPD and cases of asthma (ICD-9 CM code 493.X) before the index date. The index date for each participant was the first COPD diagnosis date. Ultimately, in total, 10,723 patients with COPD were included in the cohort study group as shown in the flowchart of . The income and age of the patients and use of medications (estrogen, oral steroid, long-acting beta-agonist [LABA], long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA], and short-acting beta-agonist [SABA]) were also included in this study.

Figure 1 Flow chart of patient selection.

Abbreviation: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification.

Exposure assessment

The ICSs analyzed in this study included fluticasone propionate and budesonide. Information on ICS exposure was extracted from the prescription database. We defined ICS users as those with at least one prescription of ICSs between the diagnosis of osteoporosis (ICD-9 CM code 733.X) and the index date. The date of prescription, the daily dose, and the number of days supplied were identified, and cumulative doses (mg) were calculated. ICSs were approved in Taiwan in June 2001 and included in the listing of NHI drug reimbursement in February 2002.

Osteoporosis outcome and follow-up

The index date for each participant was the first COPD diagnosis date. We identified the study end point as the first diagnosis of osteoporosis from outpatient claims or hospitalization records from 1997 to 2011. All the study participants were followed from the index date to end point occurrence, withdrawal from the database, or the end of 2011, whichever date came first.

Statistics

The person-years of follow-up for each case were calculated from the date of diagnosed COPD to the date of death, diagnosis of osteoporosis date, or December 31, 2011. Incident rates were calculated by dividing the case number from osteoporosis by the number of person-years of follow-up. Cox proportional hazard regression models adjusting for all potential confounders was used to estimate the relative magnitude of risk in relation to the use of ICSs. The participants were divided into three ICS exposure categories: nonusers, users of doses equal to or less than the median, and users of doses greater than the median based on the distribution of use among all cases of ICS users. Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using patients with no exposure as reference. Analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package (Version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two sided. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Totally, 10,723 patients with COPD, including ICS users (n=812) and nonusers (n=9,911), were enrolled in this study. Demographic characteristics of all patients are listed in . Among this population, 6,365 patients (59.36%) were older than 60 years and 460 of these patients were ICS users; 5,997 patients (55.93%) had an income of <15,840 New Taiwan Dollars (NTD) per month and 476 of these patients were ICS users; and 7,044 patients (65.69%) had hypertension and 612 of these patients were ICS users.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of patients in the cohort

Variable risk factors associated with osteoporosis

presents the incidence rate per 100,000 person-years in the patients with osteoporosis by age, income, and medication. presents the crude HR of osteoporosis incidence rate per 100,000 person-years in different variables. Being elderly is associated with a higher risk for osteoporosis (≥40 to <50, HR: 1; ≥50 to <60, HR: 1.85 [95% CI: 1.63–2.10]; ≥60, HR: 2.22 [95% CI: 1.99–2.47]). The relationship between the income and osteoporosis risk is as follows: <15,840, HR: 1; ≥15,840 to <21,900, HR: 0.8 (95% CI: 0.71–0.89); ≥21,900 to <34,800, HR: 1.08 (95% CI: 0.99–1.17); ≥34,800, HR: 0.62 (95% CI: 0.53–0.72). The incidence rate of osteoporosis per 100,000 person-years is 4,395.00 among ICS nonusers and 2,709.71 among ICS users (ICS nonusers HR: 1; ICS users HR: 0.64 [95% CI: 0.56–0.74]). Other medications such as LABA, LAMA, and SABA were associated with lower risk of osteoporosis. Oral steroid and estrogen were associated with higher risk of osteoporosis.

Table 2 Numbers of patients with osteoporosis and the incident rate per 100,000 person-years

Table 3 The crude HR of osteoporosis incident rate per 100,000 person-years in variable categories

Independent protective effects of ICSs on osteoporosis in patients with COPD

After adjusting for age, income, and use of medications (estrogen, oral steroid, LABA, LAMA, and SABA), the higher ICS accumulative dose is associated with a lower risk of osteoporosis (0 mg to ≤20 mg, HR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.69–1.04; >20 mg to ≤60 mg, HR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.59–1.04; >60 mg, HR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.55–0.96; P for trend =0.0023; ). The cumulative osteoporosis probability significantly decreased among the ICS users compared with nonusers (P<0.001; ).

Table 4 The HR of osteoporosis incident rate per 100,000 person-years in variable ICS dose

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that ICS users exhibit an association with a lower risk for osteoporosis and a dose–effect relationship. How can ICSs reduce osteoporosis in patients with COPD? Our explanations are as follows: first, regular treatment with ICSs can reduce systemic inflammation in COPD. There is a growing body of data to support this and it provides a plausible mechanism for clinical benefits with regard to COPD. COPD is primarily a pulmonary disease, but it has various extrapulmonary manifestations, such as deconditioning, exercise intolerance, skeletal muscle dysfunction, osteoporosis, metabolic impact, anxiety and depression, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. The comorbidities in COPD are associated with a result of “overspill” of inflammatory mediators from the lungs.Citation6 Many circulating inflammatory mediators are elevated in stable COPD and during exacerbations. C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are the known markers of systemic inflammation and are associated with osteoporosis.Citation22,Citation23 The patients with COPD with ICSs withdrawn show CRP-level reductions when retreated with ICSs, whereas patients retreated with placebo do not.Citation24 The effect of inhaled budesonide can decrease neutrophils, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and IL-8 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage sample in patients with COPD.Citation25–Citation27 Biopsies of the airways of COPD smokers with inhaled fluticasone showed decreased CD8/CD4 ratios and decreased subendothelial mast cells when compared with placebo patients.Citation28 The patients with COPD with inhaled fluticasone had fewer COPD exacerbations, which indicate that decreased airway inflammation plays a role in the beneficial effect of ICSs.Citation28 Decreased airway and lung inflammation by ICSs will decrease the overspill of inflammatory mediators to circulation. Additionally, histone deacetylases in the presence of corticosteroids for patients with COPD downregulate the transcription of inflammatory cytokines.Citation29 A recent study demonstrated that long-term administration of ICSs decelerates the annual bone mass loss in bronchitic patients, possibly by reducing both pulmonary and systemic inflammation caused by COPD.Citation30 Second, regular use of ICSs can reduce the frequency of exacerbations in patients with COPD.Citation30–Citation33 Withdrawal from treatment with ICSs may lead to exacerbations in some patients.Citation34 Decreased frequencies of acute exacerbation in patients with COPD can reduce osteoporosis. Kiyokawa et alCitation35 demonstrated that COPD exacerbations were independently associated with osteoporosis progression in a longitudinal study and recommended that osteoporosis evaluation in patients with COPD with frequent exacerbations. The frequency of acute exacerbation is related to bone metabolism markers. The frequency of acute exacerbation within the past 1 year and 25-OH vitamin D level are the independent risk factors for β-C-telopeptides of type I collagen; the frequency of acute exacerbation is the only independent risk factor for N-terminal midmolecule fragment osteocalcin.Citation36 Third, regular treatment with ICSs improves symptoms, lung function, and quality of life in patients with COPD, which can increase exercise tolerance and decrease immobility-induced bone loss. In combination with drugs treatment, patients with COPD appear to benefit from rehabilitation and maintenance of physical activities.Citation37 Although there is an association between ICSs and osteoporosis in pharmacoepidemiological studies, these studies have not fully taken COPD severity or exacerbations and their treatment into consideration. In fact, higher exacerbation rates are associated with a faster loss of lung functionCitation38 and greater worsening of health status.Citation39 Hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation is associated with a poor prognosis.Citation40 Long-term treatment with ICSs and long-acting bronchodilators improves symptoms, lung function, and quality of life and reduces the frequency of exacerbations in patients with COPD with an FEV1 <60% predicted.Citation30–Citation33 Because of there being documented adverse biological effects with regard to systemic or oral steroids, including adrenal suppression, loss of bone mass density, and risk of fracture, ICSs should be suggested in selected patients with COPD with frequent exacerbations in order to reduce systemic or oral steroids usage during exacerbation attacks.

In addition, there are many rationales for clinicians to use ICSs in patients with COPD. ICSs allow the delivery of a drug directly to the target organ and the ability to use lower cumulative doses of corticosteroid and to avoid systemic absorption. In fact, inhaled fluticasone propionate or budesonide used for the treatment of COPD is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and first-pass metabolism of the liver, thus a complete absence of systemic absorption of ICSs is minimal. Therefore, the vast majority of systemically absorbed ICSs occurs through the lungs. Less systemic absorption occurs in patients with diseased lung than in patients with normal lung function with fluticasone use.Citation41

The average age of female menopause is 49.5 years in Taiwan,Citation42 and this loss of estrogens accelerates bone loss for a period ranging from 5 years to 8 years. The distribution and effect of menopause vary in the group of 50–60 year-olds. It is well established that estrogen replacement during menopause protects bone mass.Citation42,Citation43 Current data showed that estrogen replacement was associated with osteoporosis. The possible explanation is because estrogen replacement was prescribed in menopausal females, and it was not prescribed in nonmenopausal patients with COPD. In addition, oral corticosteroid plays an important role in osteoporosis. Bronchodilators such as SABA, LABA, and LAMA can decrease the frequencies of acute exacerbation and thus associate with lower incidences of osteoporosis. Therefore, when we adjust for these related important factors for osteoporosis, the results still prove that ICS is an independent factor for osteoporosis in female patients with COPD.

Limitations of the study

There are a number of important limitations that should be highlighted. First, we used ICD-9 diagnosis to enroll the patients, thus we were unable to confirm COPD diagnoses by spirometry and to differentiate severity by FEV, either. Osteoporosis may be related to COPD severity. However, there exist many debates on the evaluations of COPD severity. The updated guidelines indicate that the evaluation of COPD severity needs multidimensional approach, such as GOLD 2014 guidelines using the Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), and the frequencies of acute exacerbation and hospitalization to divide ABCD groups. Body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (BODE) score, comorbidities, and fibrinogen or CRP biomarkers, etc, are also considered as important factors for COPD severity. So, in fact, a multidimensional data collection is not easily done. In addition, ICS use is suggested in severe and very severe patients with COPD according to GOLD guidelines. In theory, these severe and very severe patients with COPD have higher incidence or more serious osteoporosis than mild and moderate patients with COPD. However, our results show that the more severe patients with COPD using ICSs are instead less likely to have osteoporosis, which further indicates that ICSs did reduce the incidence of osteoporosis in patients with COPD. Furthermore, our study is a longitudinal population-based cohort study. When or whether the patients start to use ICSs is decided by physicians’ clinical practice. This also eliminates interference by COPD stage and severity at initial enrollment. Third, the statistical power may be criticized due to obviously unequal case numbers in two groups with and without osteoporosis, although these are true numbers in real world. Fourth, we have concerns regarding patient’s medication adherence. This is a large retrospective cohort study; indeed it is very difficult to be the same as the prospective study from which the researchers can fully understand the details of the patient’s medication adherence. Patients need to pay the part of all medical expense in Taiwan’s current health-care system. It is not logical that these patients see a doctor regularly, and not to take medicine, but they are willing to pay for long-term medical costs. Although we calculated ICS dose based on BNHI records that cannot show the dose that the patients actually used, we believe that the difference should be very limited. Fifth, menopause is a very important risk for osteoporosis and the average age of female menopause is not recorded in our data. Although we do statistical adjustment by ages (≥40 years to <50 years, ≥50 years to <60 years, and ≥60 years) and estrogen replacement, it may have a slight gap with real condition. Sixth, smoking is also a very important risk for osteoporosis and it was not recorded in our data, either. However, >95% of females are nonsmokers in Taiwan and it should be a small confounder.

Conclusion

Our findings expand on the existing knowledge in the field and provide clinicians with new information about the effectiveness of ICSs, as these relate to osteoporosis. Our study demonstrates that female patients with COPD using ICSs exhibit an association with a dose–response protective effect for osteoporosis. However, further confirmation is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 102-2314-B-182-053-MY3) and a grant from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG8C1081 and CMRPG8B0211).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: GOLD [homepage on the Internet] Available from: http://www.goldcopd.comAccessed May 4, 2016

- BarnesPJCelliBRSystemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20093351165118519407051

- ManninoDMThornDSwensenAHolguinFPrevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPDEur Respir J200832496296918579551

- SinDDAnthonisenNRSorianoJBAgustiAGMortality in COPD: role of comorbiditiesEur Respir J20062861245125717138679

- AlmagroPCabreraFJDiezJWorking Group on COPD, Spanish Society of Internal MedicineComorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD: the EPOC en Servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) studyChest201214251126113323303399

- SindenNJStockleyRASystemic inflammation and comorbidity in COPD: a result of ‘overspill’ of inflammatory mediators from the lungs? Review of the evidenceThorax2010651093093620627907

- FabbriLMLuppiFBeghéBRabeKFComplex chronic comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J200831120421218166598

- SorianoJBVisickGTMuellerovaHPayvandiNHansellALPatterns of comorbidities in newly diagnosed COPD and asthma in primary careChest200512842099210716236861

- LawMRHackshawAKA meta-analysis of cigarette smoking, bone mineral density and risk of hip fracture: recognition of a major effectBMJ199731571128418469353503

- BiskobingDMCOPD and osteoporosisChest2002121260962011834678

- CummingsSRNevittMCBrownerWSRisk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research GroupN Engl J Med1995332127677737862179

- DuboisEFRöderEDekhuijzenPNZwindermanAESchweitzerDHDual energy X-ray absorptiometry outcomes in male COPD patients after treatment with different glucocorticoid regimensChest200212151456146312006428

- LuceyDRClericiMShearerGMType 1 and type 2 cytokine dysregulation in human infectious, neoplastic, and inflammatory diseasesClin Microbiol Rev1996945325628894351

- Lung Health Study Research GroupEffect of inhaled triamcinolone on the decline in pulmonary function in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2000343261902190911136260

- PauwelsRALöfdahlCGLaitinenLALong-term treatment with inhaled budesonide in persons with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who continue smoking. European Respiratory Society Study on Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseN Engl J Med1999340251948195310379018

- FergusonGTCalverleyPMAndersonJAPrevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the TOwards a Revolution in COPD Health studyChest200913661456146519581353

- HalpernMTSchmierJKVan KerkhoveMDWatkinsMKalbergCJImpact of long-term inhaled corticosteroid therapy on bone mineral density: results of a meta-analysisAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200492201207 Quiz 207–208, 26714989387

- JonesAFayJKBurrMStoneMHoodKRobertsGInhaled corticosteroid effects on bone metabolism in asthma and mild chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20021CD00353711869676

- KuoHCChangWCYangKDKawasaki disease and subsequent risk of allergic diseases: a population-based matched cohort studyBMC Pediatr2013133823522327

- Mayo Clinic [webpage on the Internet]Risk Factors Available from: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteoporosis/basics/risk-factors/con-20019924Accessed May 4, 2016

- WenCPLevyDTChengTYHsuCCTsaiSPSmoking behaviour in Taiwan, 2001Tob Control200514suppl 1i51i5515923450

- BlackSKushnerISamolsDC-reactive proteinJ Biol Chem200427947484874849015337754

- LiangBFengYThe association of low bone mineral density with systemic inflammation in clinically stable COPDEndocrine201242119019522198912

- SinDDLacyPYorkEManSFEffects of fluticasone on systemic markers of inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004170776076515229100

- OzolDAysanTSolakZAMogulkocNVeralASebikFThe effect of inhaled corticosteroids on bronchoalveolar lavage cells and IL-8 levels in stable COPD patientsRespir Med200599121494150015946834

- CrisafulliEMenéndezRHuertaASystemic inflammatory pattern of patients with community-acquired pneumonia with and without COPDChest201314341009101723187314

- KoFWLeungTFWongGWMeasurement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, leukotriene B4, and interleukin 8 in the exhaled breath condensate in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20094798619436689

- HattotuwaKLGizyckiMJAnsariTWJefferyPKBarnesNCThe effects of inhaled fluticasone on airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled biopsy studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002165121592159612070058

- ItoKItoMElliottWMDecreased histone deacetylase activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2005352191967197615888697

- MathioudakisAGAmanetopoulouSGGialmanidisIPImpact of long-term treatment with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids on the bone mineral density of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: aggravating or beneficial?Respirology201318114715322985270

- SzafranskiWCukierARamirezAEfficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J2003211748112570112

- JonesPWWillitsLRBurgePSCalverleyPMInhaled Steroids in Obstructive Lung Disease in Europe study investigatorsDisease severity and the effect of fluticasone propionate on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbationsEur Respir J2003211687312570111

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBTORCH investigatorsSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- van der ValkPMonninkhofEvan der PalenJZielhuisGvan HerwaardenCEffect of discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the COPE studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002166101358136312406823

- KiyokawaHMuroSOgumaTImpact of COPD exacerbations on osteoporosis assessed by chest CT scanCOPD20129323524222360380

- XiaomeiWHangXLinglingLXuejunLBone metabolism status and associated risk factors in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Cell Biochem Biophys201470112913424633456

- BerryMJRejeskiWJAdairNEZaccaroDExercise rehabilitation and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stageAm J Respir Crit Care Med199916041248125310508815

- CelliBRThomasNEAndersonJAEffect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178433233818511702

- SpencerSCalverleyPMBurgePSJonesPWImpact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPDEur Respir J200423569870215176682

- Soler-CataluñaJJMartinez-GarcíaMARomán SánchezPSalcedoENavarroMOchandoRSevere acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622

- TattersfieldAEHarrisonTWHubbardRBMortimerKSafety of inhaled corticosteroidsProc Am Thorac Soc20041317117516113431

- ChowSNHuangCCLeeYTDemographic characteristics and medical aspects of menopausal women in TaiwanJ Formos Med Assoc199796108068119343980

- IsaacsAJBrittonARMcPhersonKUtilisation of hormone replacement therapy by women doctorsBMJ19953117017139914018520274