Abstract

Background

COPD self-management is a complex behavior influenced by many factors. Despite scientific evidence that better disease outcomes can be achieved by enhancing self-management, many COPD patients do not respond to self-management interventions. To move toward more effective self-management interventions, knowledge of characteristics associated with activation for self-management is needed. The purpose of this study was to identify key patient and disease characteristics of activation for self-management.

Methods

An explorative cross-sectional study was conducted in primary and secondary care in patients with COPD. Data were collected through questionnaires and chart reviews. The main outcome was activation for self-management, measured with the 13-item Patient Activation Measure (PAM). Independent variables were sociodemographic variables, self-reported health status, depression, anxiety, illness perception, social support, disease severity, and comorbidities.

Results

A total of 290 participants (age: 67.2±10.3; forced expiratory volume in 1 second predicted: 63.6±19.2) were eligible for analysis. While poor activation for self-management (PAM-1) was observed in 23% of the participants, only 15% was activated for self-management (PAM-4). Multiple linear regression analysis revealed six explanatory determinants of activation for self-management (P<0.2): anxiety (β: −0.35; −0.6 to −0.1), illness perception (β: −0.2; −0.3 to −0.1), body mass index (BMI) (β: −0.4; −0.7 to −0.2), age (β: −0.1; −0.3 to −0.01), Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage (2 vs 1 β: −3.2; −5.8 to −0.5; 3 vs 1 β: −3.4; −7.1 to 0.3), and comorbidities (β: 0.8; −0.2 to 1.8), explaining 17% of the variance.

Conclusion

This study showed that only a minority of COPD patients is activated for self-management. Although only a limited part of the variance could be explained, anxiety, illness perception, BMI, age, disease severity, and comorbidities were identified as key determinants of activation for self-management. This knowledge enables health care professionals to identify patients at risk of inadequate self-management, which is essential to move toward targeting and tailoring of self-management interventions. Future studies are needed to understand the complex causal mechanisms toward change in self-management.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

COPD is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases worldwide and the fourth leading cause of mortality.Citation1,Citation2 Increased burden of COPD is expected due to aging of the population and continued exposure to COPD risk factors.Citation1,Citation3 To address the burden on both patients and society, self-management has become increasingly important.Citation4–Citation6 Self-management is defined as “an individual’s ability to detect and manage symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition”.Citation7 Self-management can support COPD patients to manage their symptoms, prevent complications, and make adequate decisions on medication, exercise, breathing techniques, diet, and contacting health care providers.Citation4,Citation8,Citation9

The pivotal objective of self-management interventions is to change health behaviors and to equip patients with skills to actively participate in the management of their disease.Citation4,Citation10 Previous research has shown that self-management interventions have positive effects on disease outcomes, health-related quality of life, and health care costs.Citation5,Citation11,Citation12 A substantial proportion of COPD patients, however, do not respond or comply with self-management interventions.Citation5,Citation10,Citation13 The large variance in effectiveness between patients presumes that it is unlikely that one intervention fits all patients.Citation10,Citation13 Health care professionals play a major role in providing self-management support, but patients’ initial self-management capabilities are often not determined by these professionals, frequently resulting in a “one size fit all approach”.Citation10,Citation14

To identify COPD patients who are more engaged in self-management and patients who encounter difficulties in performing adequate self-management, more insight into patient and disease characteristics associated with self-management behavior is needed.Citation8,Citation10 The process toward adequate self-management requires an increase in knowledge, skills, and confidence for self-management, which is defined as the level of activation for self-management.Citation14 Higher levels of activation reflect better capacity to self-manage one’s disease.Citation14,Citation15 In a recent study, we investigated factors associated with activation for self-management in a large population of patients with various chronic diseases (eg, diabetes mellitus type II, chronic heart failure, chronic renal disease, and COPD).Citation16 This study identified age, body mass index (BMI), educational level, financial distress, physical health status, depression, illness perception, social support, and underlying disease as important determinants, explaining 16% of variance in activation for self-management.Citation16 These associations were disease transcending except for social support. More specific, the association between COPD and activation was dependent on social support, while this was not observed for other conditions.Citation16 In this study, no specific COPD-related factors were taken into account and, therefore, factors explaining variance in activation for self-management in COPD patients specifically remain unclear. Previous studies have shown that COPD-specific characteristics such as dyspnea and disease severity may also be related to self-management behavior.Citation8,Citation17,Citation18 Investigating the association between COPD-specific determinants and activation for self-management, combined with previously investigated determinants, may contribute to a thorough understanding of factors influencing self-management behavior in COPD patients.

To move toward the development of targeted and tailored self-management interventions with improved efficiency and (cost-) effectiveness, knowledge on key patient and disease characteristics of activation for self-management in COPD patients specifically is needed. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify key determinants of activation for self-management in patients with COPD.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive study was performed with a cross-sectional research design. The study was conducted in one secondary and two primary care settings in the Netherlands and was part of a larger study.Citation16 The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center of Utrecht.

Study population and recruitment

Patients diagnosed with mild-to-very severe COPD were selected by the attending physician according to the following inclusion criteria: a clinical diagnosis of COPD meaning a post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio <70% and age above 40 years. In secondary care, patients should have visited the outpatient clinic in the past 6 months to reduce the risk of including patients who are deceased or are no longer under treatment. Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of lung cancer, cognitive impairments, language or communication problems, and a life expectancy of less than 3 months.

The sample size was calculated to allow sufficient power for a multiple linear regression analysis using 20 variables. According to the ratio of number of predictor variables to number of participants (1:10), a sample size of at least 200 participants was required.Citation19 Patients were selected by chart review according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients received an invitation letter from their attending physician to participate in this study. Attached with the invitation letter, patients also received a letter with study information, an informed consent form, a questionnaire, and a pre-addressed return envelope. To enhance recruitment rates, patients were sent a reminder after 3 weeks if the IC form was not returned. By signing the IC form, patients gave consent to consult their medical chart to obtain additional information.

Data collection

Data were collected by means of administering a questionnaire and medical chart review. The questionnaire was a composition of Dutch-validated questionnaires and a set of questions to determine sociodemographic characteristics.

The primary outcome activation for self-management was measured by the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13), a 13-item instrument that assesses self-reported knowledge, skills, and confidence for self-management.Citation14,Citation20,Citation21 A positive change in activation has shown to be associated with positive changes in various self-management behaviors.Citation15 Items are scored on a five-point scale. The sum of these scores is converted in a 0–100 point scale.Citation20,Citation22 Based on cut-off points for the four levels of activation – level 1 (≤47.0 points), level 2 (47.1–55.1 points), level 3 (55.2–67 points), and level 4 (≥67.1 points) – the individual patients’ level of activation can be determined.Citation20,Citation22 A higher level refers to higher activations scores.Citation14 Patients in level 1 are often passive and lack confidence for self-management resulting in low self-management engagement. Patients in level 2 become aware that they should be involved in their care, although there remain gaps in knowledge and skills. Patients in level 3 gain confidence for self-management and start to take action. The fourth, and highest, level of activation includes patients who have adopted new behaviors and are challenged to maintain these behaviors over time. Therefore, patients with higher levels of activation are considered to be better self-managers.Citation14,Citation15,Citation23

The PAM-13 is translated in Dutch and validated in COPD patients showing good internal consistency (α=0.88). Item-rest correlations were moderate-to-strong and test–retest reliability was moderate.Citation21

Determinants of activation for self-management were measured using the following instruments. Health status was measured by the Short Form–12 Health Survey (SF-12), a short version of the Short Form–36 (SF-36).Citation24,Citation25 The 12-item SF-12 measures both physical and mental health.Citation26 Item scores result in two summary scores on a 0–100 point scale. Higher scores refer to a better health status. Presence of anxiety or depression was measured by the Dutch-validated Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).Citation27,Citation28 The HADS includes two seven-item subscales (anxiety and depression) both with a score range of 0–21.Citation28 Higher scores refer to a higher state of anxiety or depression, with cut-off point ≥11 indicating a depression or anxiety disorder. The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ) was used to measure illness perception.Citation29 The B-IPQ consists of eight items, each scored on a scale from 1 to 10, resulting in an overall score (range: 0–80). Higher scores indicate a more negative illness perception. Assessment of reproducibility was performed with Dutch COPD patients and showed moderate to good reliability.Citation29 The 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support was used to assess social support.Citation30,Citation31 Items were scored on a seven-point scale. Higher scores indicate higher perceived support.Citation30,Citation31 Validity and reliability were confirmed by Dutch cardiac patients and their partners.Citation32

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, BMI, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, living situation, and smoking habits. Socioeconomic status was operationalized in three separate variables: educational level, financial distress, and care allowance as a proxy for income. Operationalization of these determinants is detailed in .

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the study population

Disease characteristics included COPD severity, COPD duration, current exacerbation, and comorbidities. Severity of COPD was obtained from the medical chart and classified into four stages of Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), which were determined using FEV1/FVC and FEV1% predicted data.Citation1 In case of missing lung function data, GOLD stage as reported by the physician was used. To complement FEV1% predicted in the classification of COPD severity, dyspnea was measured by the five-point Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. A higher score indicates a higher degree of perceived breathlessness.Citation33 COPD duration was determined by number of years since diagnosis. Current exacerbation at the time of the measurement was examined by asking whether patients currently used a course of antibiotics and/or prednisolone. Furthermore, comorbidities obtained from chart review were assessed by the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI).Citation34,Citation35 The CCI is based on ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases – tenth revision) codes and defines 19 comorbidities. A weighted score, based on the relative risk of mortality at 1 year, was assigned to each comorbidity with a total range of 0–37.Citation35

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).Citation36 Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline characteristics. Means and standard deviations were used to describe continuous variables, whereas frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables.

Patients were excluded when all 13 questions of the PAM-13 were answered identically or showed more than seven missing.Citation21,Citation22 Analysis of missing values of all determinants was performed and showed 2% missing variables, distributed among 31% of the cases. Multiple imputation was used to deal with missing data, since this may reduce bias when data are missing at random.Citation37 Data analysis was performed in ten imputed data sets.

Univariate linear regression analysis was used to analyze the association between single determinants and activation for self-management, rather as a method for selecting candidate predictors. Pooled estimates of the association, derived from the estimates per imputed dataset as created by SPSS, are used in the “Results” section.

A stepwise backward multiple linear regression analysis was performed in order to identify explanatory variables of activation for self-management. Variables were excluded in order of the highest P-value. A significance level of 20% was used to keep a variable in the model. This method was applied to each of the ten imputation data sets separately and resulted in ten sets of selected variables. The majority method was used to keep variables in the final model, which consisted of variables that were selected in 50% or more of the ten data sets.Citation38 To calculate pooled R2 statistics, Fisher’s r to z transformation was used.Citation39 Assumptions of linearity, multicollinearity (R>0.8), and homoscedasticity were checked and approved. Some continuous variables did not completely meet the assumption for normal distribution. Therefore, generalized linear models were used with robust standard errors in the linear regression analysis.

Results

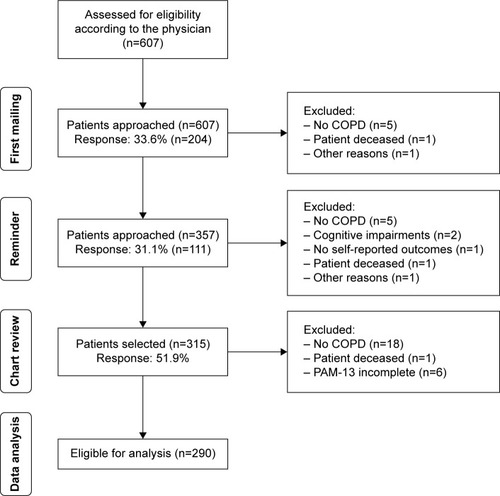

In total, 607 eligible COPD patients were invited for this study, of which 315 patients (52%) agreed to participate. A total of 42 patients were excluded during the process of recruitment and data collection. Finally, 290 participants were found to be eligible for analysis ().

The mean age of participants was 67.2 (SD 10.3) and 63.4% were males. The majority of participants were Dutch (92.4%), married (66.2%), unemployed (81.7%), non-smokers (68.3%), and had a low-to-medium education level (81.7%). Most participants had moderate COPD as mean FEV1% predicted was 63.6 (GOLD stage 2). In addition, a majority of 63.1% of the participants had a MRC score below three. Nearly half of the population was diagnosed with COPD for more than 5 years (46.6%). Other patients’ characteristics are detailed in .

Activation for self-management

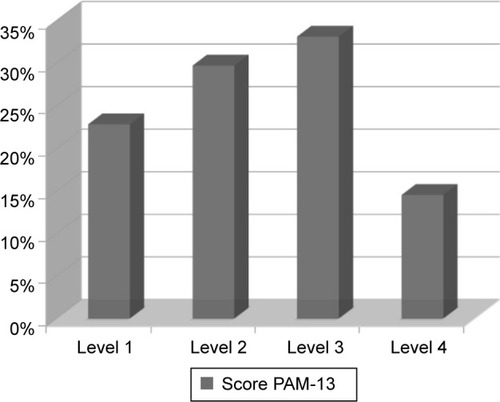

The mean activation score (PAM-13) was 54.7 (SD 10.4). shows the prevalence of different levels of activation for self-management among the study population and details that participants were almost equally distributed in PAM-13 levels 2 and 3 (29.7 vs 33.1, respectively). Poor activation for self-management (level 1) was observed among 22.8% of the participants. A minority of 14.5% of the participants was activated for self-management and scored on level 4 ().

Figure 2 Distribution of different PAM levels.

Abbreviation: PAM, Patient Activation Measure.

Determinants associated with activation for self-management

Univariate associations between determinants and activation for self-management are presented in . Physical health status, mental health status, anxiety, depression, illness perception, BMI, education level, dyspnea, and GOLD stage were significantly associated with activation for self-management (P<0.05).

Table 2 Univariate linear regression and multiple linear regression to analyze the association between multiple determinants and activation for self-management

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed six explanatory determinants of activation for self-management: anxiety, illness perception, BMI, age, GOLD stage, and comorbidities ().

Increased level of anxiety (β: −0.35; CI: −0.64 to −0.06), a more negative illness perception (−0.17; −0.28 to −0.06), increased BMI (−0.42; −0.65 to −0.19), increased age (−0.14; −0.26 to −0.01), increased GOLD stage (2 vs 1: −3.15; −5.77 to −0.54, 3 vs 1: −3.37; −7.07 to 0.32), and less comorbidities (0.79; −0.19 to 1.77) were associated with a decrease in activation for self-management (P<0.2). For GOLD stage, a statistical significant association was observed specifically in GOLD stage 2 vs 1 (P<0.5). The explained variance (R2) of the multivariable model was 0.17. High correlations were observed between mental and physical health (R=0.76) and anxiety and depression (R=0.73).

Discussion

This study has provided insight into the prevalence of different levels of activation for self-management and identified patient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in COPD patients. Only a minority of COPD patients was activated for self-management. The main finding was that increased anxiety, a more negative illness perception, higher BMI, higher age, more disease severity, and less comorbidities were associated with a lower activation for self-management. These variables explained 17% of the variance in activation for self-management.

Activation for self-management in the study population, represented by the mean activation score, was lower compared to a previous Dutch study including COPD patients.Citation21 This might be explained by the fact that this study focused on various chronic disease patients who were younger (58.7 vs 67.2 years).Citation21 In our study, only a minority of participants was activated for self-management (level 4), which indicates major room for improvement. Slightly more than half of the participants were in levels 2 and 3 and nearly a quarter was considered to be a poor self-manager (level 1). In contrast, another Dutch study that focused on activation for self-management in COPD patients showed that most patients were in levels 3 and 4.Citation40 Since both other Dutch studies sampled patients from a national panel, this may have positively affected the outcome as these patients might be more activated for self-management.

This study identified anxiety, illness perception, BMI, age, GOLD stage, and comorbidities as explanatory determinants of activation for self-management. This is partly in line with previous studies focusing on self-management in COPD patients. A previous literature review identified anxiety, illness perception, and dyspnea as factors influencing self-management.Citation8 In addition, associations with age and disease severity were observed in another study focusing on self-management.Citation18 On the contrary, socioeconomic status and social support were expected to be related with self-management,Citation8 although no significant association with activation for self-management was observed in our study. This might be due to the large heterogeneity in self-management outcome parameters used in previous studies and our specific focus on activation for self-management. Remarkably, comorbidities and BMI were identified as key determinants in our study, while this has not been reported in previous studies to our knowledge. A previous study using the PAM-13 in COPD patients identified no associations with age and presence of comorbidities, although a small association with dyspnea was found.Citation40 In our study, age and comorbidities were identified as key determinants of activation for self-management which may be explained by the fact that we included multiple determinants in our model, investigating the relative influence of each individual determinant, and the fact that patients in our study had relatively more comorbidities.

The identified determinants were partly in line with findings from our larger study focusing on determinants for self-management in various chronic diseases.Citation16 In line with that study, the age, BMI and illness perception were identified as key determinants. On the contrary, education level, financial distress, physical health status, depression, and social support were not identified as key determinants in this current study. In this study, anxiety was identified as a key determinant. It is important to note that anxiety was highly correlated with depression and mental health status. This may indicate that emotional distress in general is an important determinant of self-management behavior. Furthermore, contrasting was that disease severity emerged as a key determinant in this study, though not in the larger study. This might be explained by the fact that disease severity was standardized for various chronic diseases in the larger study, leading to broader categories of severity. Finally, comorbidity was a key determinant in this study, indicating that COPD patients with several comorbidities seem more activated for self-management. This might be due to the fact that these patients already have more experience with health care and know how to cope with their disease. The results of this study indicate that anxiety, disease severity, and comorbidity were more important in identifying the level of activation in COPD patients than they were in the mixed group of patients with various chronic conditions.

The explained variance was 17%, which is lower compared to previous studies on explanatory variables of self-management in COPD patients (varying from 31% to 34%).Citation18,Citation41 The identified key determinants could only explain the variance of activation for self-management to a limited extent. The remaining variance may be explained by other types of factors influencing activation for self-management, for example, self-efficacy or received self-management support from health care professionals. Self-efficacy was not included in this study since the PAM-13 already includes items focusing on self-efficacy. However, in social cognitive theory, self-efficacy is considered to be an important intermediate in the causal chain toward adoption of self-management skills and behavioral change.Citation42,Citation43

An important strength of this study was that a wide range of determinants was analyzed simultaneously in a relatively large study population. Inclusion from both primary and secondary care had a positive impact on the generalizability of the results since this maximizes variation in COPD severity. Finally, the response rate of more than 50% was higher than the expected rate of 40%, which strengthens the external validity of this study. A limitation of this study was that patients were recruited by physicians in different settings, which may have resulted in selection bias. In primary care, a few patients were considered eligible by their physician based on GOLD stage, while lung function data were missing. Those participants were included in the analysis when GOLD stage was explicitly listed in the chart and patients received active treatment for their COPD. Furthermore, in this study less non-native patients were included than expected based on the data of the Dutch population,Citation44 which might have been due to language barriers.

The acquired knowledge on explanatory determinants of activation for self-management is important for all health care professionals supporting COPD patients in self-management, as it allows them to make a risk assessment of inadequate engagement in self-management based on an individual patient profile. Based on the study results, specific attention should be paid to relatively older patients, with a relatively high weight, a more negative illness perception, more severe COPD, less comorbidities, and emotional disturbances. This stresses the need for adequate assessment on patient-related factors that can be influenced such as illness perception, anxiety, and BMI, as improving these factors may lead to increased quality of life or health status.Citation45,Citation46 For example, health care professionals should pay more attention to identifying negative illness perceptions by asking patients how they experience their COPD and how COPD symptoms influence their daily lives,Citation46 so that they can anticipate on these perceptions in future consultations.

For patients at risk for inadequate engagement in self-management, intensifying self-management support seems important to increase the likelihood of engagement in self-management. First, adequate assessment by health care professionals on patient knowledge, skills, and confidence is needed to identify problem areas allowing them to anticipate on these individual problem areas with tailored strategies. Intensifying self-management support may then consist of spending more time on education or to provide additional materials to increase patients’ knowledge, to amplify action planning and decision support to increase patients skills, or to add reinforcement consultations to increase patients confidence for self-management.

The knowledge on determinants of activation for self-management may help health care professionals to make a first step in targeting and tailoring their interventions. Assessment on engagement in self-management based on patient profiles, and identifying behavioral needs, may contribute to individualizing self-management interventions. Dose, content, and modus of self-management interventions should then be tailored to individual patient needs and capabilities.

More research is needed to investigate barriers and facilitators of activation for self-management in COPD patients including a focus not only on other patient-related factors, such as self-efficacy, but also on provider and health care system characteristics. These studies should focus on identifying causal relationships between determinants and activation for self-management. Longitudinal studies are required to determine key determinants of change in activation for self-management. This knowledge is essential to eliminate barriers of activation for self-management and will contribute to targeting and tailoring of self-management interventions.

Conclusion

This study showed that only a minority of COPD patients is activated for self-management, which implies that there is great potential for improvement in self-management and subsequently in health outcomes. This study found that increased anxiety, a more negative illness perception, increased BMI, increased age, increased disease severity, and less comorbidities were associated with a decrease in activation for self-management in COPD patients. This knowledge contributes to identification of patients at risk of inadequate engagement in self-management activities, which is an essential first step toward targeting and tailoring individualized self-management interventions in the future. To be able to thoroughly understand the complex causal mechanisms toward change in self-management behavior, future research is needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who participated and acknowledge all health centers for their cooperation in this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Updated 2016 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report%202016.pdfAccessed February 2, 2016

- World Health OrganizationThe global burden of disease. Updated 2004 Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf?ua=1Accessed October 28, 2015

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- BourbeauJvan der PalenJPromoting effective self-management programmes to improve COPDEur Respir J200933346146319251792

- ZwerinkMBrusse-KeizerMvan der ValkPDSelf management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD00299024665053

- SpruitMASinghSJGarveyCAn official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20131888e13e6424127811

- BarlowJWrightCSheasbyJTurnerAHainsworthJSelf-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a reviewPatient Educ Couns200248217718712401421

- DislerRTGallagherRDDavidsonPMFactors influencing self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative reviewInt J Nurs Stud201249223024222154095

- BourbeauJNaultDSelf-management strategies in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseClin Chest Med2007283617628vii17720048

- EffingTWBourbeauJVercoulenJSelf-management programmes for COPD: moving forwardChron Respir Dis201291273522308551

- AdamsSGSmithPKAllanPFAnzuetoAPughJACornellJESystematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and managementArch Intern Med2007167655156117389286

- BourbeauJJulienMMaltaisFReduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management interventionArch Intern Med2003163558559112622605

- TrappenburgJJonkmanNJaarsmaTSelf-management: one size does not fit allPatient Educ Couns201392113413723499381

- HibbardJHMahoneyERStockardJTuslerMDevelopment and testing of a short form of the patient activation measureHealth Serv Res2005406 Pt 11918193016336556

- HibbardJHMahoneyERStockRTuslerMDo increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors?Health Serv Res20074241443146317610432

- Bos-TouwenISchuurmansMMonninkhofEMPatient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in patients with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure and chronic renal disease: a cross-sectional survey studyPLoS One2015105e012640025950517

- CrammJMNieboerAPSelf-management abilities, physical health and depressive symptoms among patients with cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetesPatient Educ Couns201287341141522222024

- WarwickMGallagherRChenowethLStein-ParburyJSelf-management and symptom monitoring among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Adv Nurs201066478479320423366

- PeduzziPConcatoJKemperEHolfordTRFeinsteinARA simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysisJ Clin Epidemiol19964912137313798970487

- HibbardJHStockardJMahoneyERTuslerMDevelopment of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumersHealth Serv Res2004394 Pt 11005102615230939

- RademakersJNijmanJvan der HoekLHeijmansMRijkenMMeasuring patient activation in the Netherlands: translation and validation of the American short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM13)BMC Public Health201212157722849664

- Insignia HealthPatient Activation Measure (PAM) 13, licence materials2011

- Insignia HealthPatient Activation Measure (PAM) Survey levels Available from: http://www.insigniahealth.com/products/pam-surveyAccessed March 10, 2016

- WareJJrKosinskiMKellerSDA 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validityMed Care19963432202338628042

- AaronsonNKMullerMCohenPDTranslation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populationsJ Clin Epidemiol19985111105510689817123

- MolsFPelleAJKupperNNormative data of the SF-12 health survey with validation using postmyocardial infarction patients in the Dutch populationQual Life Res200918440341419242822

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand19836763613706880820

- SpinhovenPOrmelJSloekersPPKempenGISpeckensAEVan HemertAMA validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjectsPsychol Med19972723633709089829

- De RaaijEJSchroderCMaissanFJPoolJJWittinkHCross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire-Dutch Language VersionMan Ther201217433033522483222

- ZimetGDDahlemNWZimetSGFarleyGKThe Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social SupportJ Pers Assess1988523041

- ZimetGDPowellSSFarleyGKWerkmanSBerkoffKAPsychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social SupportJ Pers Assess1990553–46106172280326

- PedersenSSSpinderHErdmanRADenolletJPoor perceived social support in implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) patients and their partners: cross-validation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social supportPsychosomatics200950546146719855031

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRGarnhamRJonesPWWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCRA new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validationJ Chronic Dis19874053733833558716

- SundararajanVHendersonTPerryCMuggivanAQuanHGhaliWANew ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortalityJ Clin Epidemiol200457121288129415617955

- IBM CorpIBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0Armonk, NYIBM Corp2012

- DondersARvan der HeijdenGJStijnenTMoonsKGReview: a gentle introduction to imputation of missing valuesJ Clin Epidemiol200659101087109116980149

- VergouweYRoystonPMoonsKGAltmanDGDevelopment and validation of a prediction model with missing predictor data: a practical approachJ Clin Epidemiol201063220521419596181

- HarelOThe estimation of R2 and adjusted R2 in incomplete data sets using multiple imputationJournal of Applied Statistics2009361011091118

- BaanDHeijmansMSpreeuwenbergPRijkenMZelfmanagement vanuit het perspectief van mensen met astma of COPD Available from: http://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Rapport-Zelfmanagement-mensen-met-COPD-of-Astma.pdfAccessed March 21, 2016

- WangKYSungPYYangSTChiangCHPerngWCInfluence of family caregiver caring behavior on COPD patients’ self-care behavior in TaiwanRespir Care201257226327221762551

- BourbeauJSelf-management interventions to improve outcomes in patients suffering from COPDExpert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res200441717719807337

- BanduraASelf-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral changePsychol Rev1977842191215847061

- SanderseCVerweijAde BeerJEtniciteit: Wat is de huidige situatie? Available from: http://www.nationaalkompas.nl/bevolking/etniciteit/huidig/Accessed March 1, 2016

- TsiligianniIKocksJTzanakisNSiafakasNvan der MolenTFactors that influence disease-specific quality of life or health status in patients with COPD: a review and meta-analysis of Pearson correlationsPrim Care Respir J201120325726821472192

- WeldamSWLammersJWHeijmansMJSchuurmansMJPerceived quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a cross-sectional study in primary care on the role of illness perceptionsBMC Fam Pract20141514025087008