Abstract

Background and objective

Airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) results in a decrease in oxygen transport to the brain. The aim of the present study was to explore the alteration of spontaneous brain activity induced by hypoxia in patients with COPD.

Patients and methods

Twenty-five stable patients with COPD and 25 matching healthy volunteers were investigated. Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) of blood oxygenation level-dependent signal at resting state in the brain was analyzed using functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Results

Whole-brain analysis using functional magnetic resonance imaging revealed significant decreases in ALFF in the bilateral posterior cingulate gyri and right lingual gyrus and an increase in ALFF in the left postcentral gyrus of patients with COPD. After controlling for SaO2, patients with COPD only showed an increase in ALFF in the left postcentral gyrus. Region of interest analysis showed a decrease in ALFF in the left precentral gyrus and an increase in ALFF in the left caudate nucleus of patients with COPD. In all subjects, ALFF in the bilateral posterior cingulate gyri and right lingual gyrus showed positive correlations with visual reproduction.

Conclusion

We demonstrated abnormal spontaneous brain activity of patients with COPD, which may have a pathophysiologic meaning.

Introduction

The brain maintains a high level of spontaneous neuronal activity, which is relevant for human behavior.Citation1–Citation4 Low-frequency fluctuation (0.01–0.08 Hz) of blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal in the brain has been proven to be highly correlated with this spontaneous activity.Citation5 Synchronous low-frequency fluctuation between motor cortices was first observed by Biswal et al.Citation6 Afterward, an analysis of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) was done by Zang et alCitation7 and ALFF examination has been widely used in studies of various mental disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,Citation7 schizophrenia,Citation8,Citation9 posttraumatic stress disorder,Citation10 and mood disorder.Citation11 Recently, abnormal ALFF at resting state has been linked with cognitive impairments.Citation12–Citation15

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a syndrome of chronic progressive airflow limitation, which results in decrease in oxygen transport to the brain. Spontaneous neuronal activity is thought to consume the majority of total brain energy,Citation16,Citation17 and thus the spontaneous neuronal activity is inevitably influenced by a reduction in the supply of energy supply caused by hypoxia. Hypoxia has been proven to change the microenvironment around neurons,Citation18,Citation19 inhibit synaptic transmission,Citation20,Citation21 and impair spontaneous and task-stimulated neuronal activity.Citation22–Citation26 Taken together, we hypothesized that hypoxia could suppress spontaneous neuronal activity in the brain of patients with COPD.

In the present study, 25 stable patients with COPD were recruited for examining ALFF in the brain. Changes of resting-state neuronal networks in the brain of patients with COPD were identified by independent component analysis (ICA).Citation27 However, although ICA can measure BOLD signal synchrony, it is difficult to pinpoint which area is responsible for the observed abnormality in connectivity. Useful information about neural process may be present in the oscillatory amplitude envelope.Citation7,Citation28 Therefore, an alternative way of measuring regional brain activity during the resting state is to examine the ALFF of the BOLD signal. Furthermore, ALFF has high levels of reliability and consistency in terms of the spatial pattern generated.Citation28 Such technique may therefore be a useful complement to ICA of interregional coherences between multiple BOLD signals.Citation29

Materials and methods

Subjects

Twenty-five patients were included in this study from Zhongshan Hospital of Xiamen University (Xiamen, People’s Republic of China). Patients received treatment for 30–45 days and were in a stable condition. The controls were 25 healthy volunteers, with matched age, sex, and education. All subjects were free from a history of neurological, cerebrovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic diseases that are known to affect cognition. None of the subjects were current smokers. Patients were provided with therapy, including the inhalation of Bricanyl, Ventolin, ipratropium bromide, or budesonide. All subjects were right handed. Demographic characteristics of subjects are shown in . The procedure was fully explained to all subjects, and written informed consent obtained. The experimental protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of Xiamen University.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of patients with COPD and healthy controls

Physiological and neuropsychological tests

Physiological and neuropsychological tests were conducted before a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Physiological tests included the arterial blood gas analysis and pulmonary function measure. Neuropsychological tests included the visual reproduction test and figure memory test adopted from the Chinese revised version of Wechsler Memory Scale.Citation30 The detailed test information was described in our previous study.Citation31 An independent t-test measured between-group differences. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

MRI data acquisition

Resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) images were acquired on a Siemens Trio Tim 3.0T (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at Magnetic Resonance Center, Zhongshan Hospital, Xiamen University, using an echo-planar imaging sequence: TR/TE =3,000 ms/30 ms, flip angle =90°, matrix =64×64, voxel size =3.4×3.4×3.75 mm3, FOV =24×24 cm2, slices =38, slice thickness =3 mm. All subjects lay in the scanner with their eyes closed, but awake. T1 and T2 images were also scanned for any incidental findings. Data analyses were conducted by two researchers who were blind to the status of the subjects.

ALFF analysis

Image preprocessing was performed using data processing assistant for resting-state fMRI (Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI) implemented in SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The first four time points were discarded for signal equilibrium. Then slice timing correction and realignment for head motion correction were performed for the remainder data. Finally, the images were spatially smoothed using a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm full-width at half-maximum.

ALFF was calculated with RESting-state fMRI data analysis Toolkit (REST) (http://restfmri.net). Before ALFF calculation, the linear trends of the time series were removed. A temporal band-pass filter (0.01–0.08 Hz) was used to remove low-frequency drifts and respiratory and cardiac high-frequency noise. Each filtered voxel’s time series was transformed into the frequency domain by the fast Fourier transform, and then the power spectrum was obtained. The square root was calculated at each frequency of the power spectrum and averaged across 0.01–0.08 Hz at each voxel. This averaged square root was taken as the ALFF. For the purposes of standardization, the ALFF of each voxel was divided by the global mean ALFF. The global mean ALFF was calculated within a brain mask that excluded the background.

In addition, the regions that showed significant differences in the density of gray matter (GM) between patients with COPD and controls were selected for region of interest (ROI) analysis (Zhang et alCitation31), which included the left precentral gyrus, bilateral anterior cingulate gyri, bilateral insula, bilateral thalamus, and head of left caudate nucleus.

Two-sample t-test was performed to assess the ALFF difference between groups, with age, sex, education, and pack-years smoking as covariates. Multiple comparisons were performed using Alphasim program determined by Monte Carlo simulation in REST. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 (corrected). We further performed an additional group-level analysis that not only regressed out the aforementioned four nuisance variates but also controlled for SaO2 to observe the influence of SaO2 on the regional ALFF.

Correlation analysis

Average ALFF values of all voxels in the clusters that showed significant group differences were extracted using REST. Partial correlation was used to analyze the relationships of ALFF values with neuropsychological measurements. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 (corrected for Bonferroni multiple comparisons), with sex, age, and education as covariates.

Results

Physiological and neuropsychological tests

Compared with controls, patients with COPD had markedly lower pulmonary measurements in 1 second over forced vital capacity (P<0.001), forced expiratory volume (P<0.001), and forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (P<0.001), and had lower artery SaO2 (P=0.003) and higher PCO2 (P<0.001). COPD patients had significantly lower scores in visual reproduction (P=0.031) and figure memory (P=0.010).

Regional ALFF values

There was no significant difference in global mean ALFF between patients with COPD and controls across all 76 time points (F(1, 48) =0.654, P=0.457).

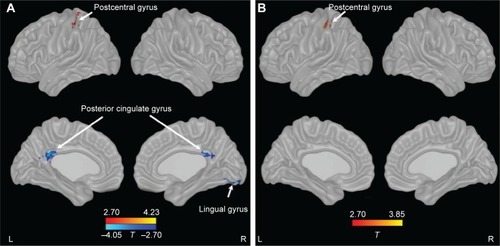

Compared with controls, patients with COPD showed significant decreases in ALFF in bilateral posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and right lingual gyrus and an increase in ALFF in the left postcentral gyrus. After controlling for SaO2, patients with COPD only showed an increase in ALFF in the left postcentral gyrus (; ).

Table 2 Regional information of changed ALFF in patients with COPD

Figure 1 Changes of ALFF in patients with COPD compared with controls.

Abbreviations: ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; L, left; R, right.

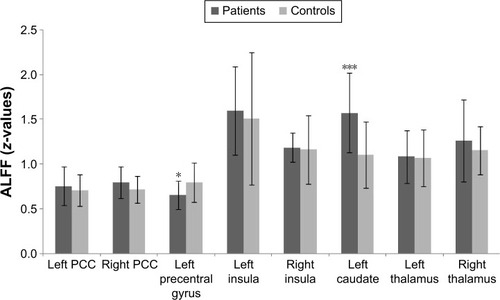

ROI analysis showed that ALFF was decreased in the left precentral gyrus (P=0.021) and increased in the left caudate nucleus (P<0.001) in patients with COPD compared with controls (). There were no significant differences between groups in the bilateral anterior cingulate gyri, insula, and thalamus.

Figure 2 Regional ALFF in the brain of patients with COPD compared with controls by ROI analysis.

Abbreviations: ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; ROI, region of interest.

Correlations of regional ALFF

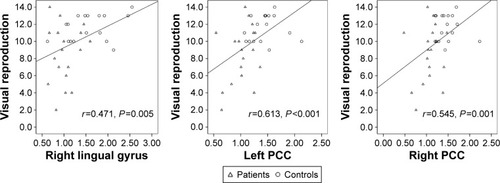

In patients with COPD and controls, ALFF in the bilateral PCC and right lingual gyrus had positive correlations with visual reproduction score ().

Discussion

In the present study, based on whole-brain and ROI analysis, abnormal spontaneous neuronal activities were detected in several brain regions of patients with COPD. Among these regions, the ALFF in bilateral PCC and right lingual gyrus showed significant correlations with the poor performance in visual reproduction.

After controlling for SaO2, the group differences in ALFF in bilateral PCC and right lingual gyrus did not exist, which suggested hypoxia-diminished basal BOLD signal. A number of studies support our finding. For example, acute hypoxia-induced depression of neuronal activity was recorded in a hippocampal brain slice;Citation24,Citation32,Citation33 chronic hypoxia has also been proven to reduce neuronal excitability;Citation26 after exposure to high altitude for 5 weeks, the magnitude of BOLD response to visual stimulation was significantly decreased;Citation22 in rats, after inspiration of low O2 concentration, forepaw-stimulated increase of BOLD signal was significantly smaller.Citation23 Previous studies have shown that cognitive impairments in patients with COPD can be reversed by oxygen therapy.Citation34,Citation35 We therefore suggested that cognitive impairments in patients with COPD may be attributed to hypoxia-reduced neuronal activity.

Patients with COPD in our study developed hypercapnia. In vivo electrophysiological studies have shown that hypercapnia directly increased discharge frequencies and decreased modal interspike intervals for medullary respiratory neurons in decerebrate catsCitation36 and reduced postsynaptic potentials of neocortical and spinal neurons.Citation37 Based on resting-state fMRI, Marshall et alCitation38 found significantly decreased brain functional connectivity in almost all brain lobes induced by mild carbon dioxide. In another aspect, elevated blood CO2 can relax arteriolar smooth muscle, leading to an increase in cerebral blood flow. Increasing blood flow then via vasoactive stimuli increases venous oxygen saturation due to the deoxyhemoglobin removal, causing a concurrent increase in the BOLD signal. For example, hypercapnia was found to be associated with widespread BOLD signal increases, predominantly within the gray matter;Citation39 BOLD signals increased after rats was subjected to 5%–10% CO2;Citation23 BOLD signal response to increasing arterial PaCO2 showed a sigmoidal model.Citation40

Inflammation exists in stable COPD and is enhanced during exacerbations.Citation41 In stable patients with COPD, increased levels of inflammatory factors such as C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, leukocytes, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α were found to be associated with reduced lung function.Citation42 Unfortunately, our study did not measure serum inflammatory factors in patients with COPD. Many studies have shown that these proinflammatory cytokines play a key role in the regulation of synaptic transmission and plasticity in the absence and presence of acute hypoxia.Citation21 An fMRI study revealed that IL-β and tumor necrosis factor receptor-II were positively associated with ventral prefrontal activation.Citation43 Endotoxin has been proven to enhance neural activity in a number of regions in response to positive and negative feedbacks.Citation44,Citation45 Taken together, these data suggest changes of functional activity in the brain of patients with COPD may be attributed to inflammatory factors.

Voluntary hyperpnea has been shown to be associated with significant neural activity in a number of regions of the brain, including the primary sensory cortex.Citation46 Consequently, in our study, the increased neuronal activity in the left post-central gyrus and left caudate nucleus of patients with COPD may be driven in large part by hyperpnea.Citation31

Similar to our findings in patients with COPD, abnormal neuronal activities in PCC and lingual gyrus have been found in hypoxic patients. For example, increases in activity of alpha 2 frequency band in bilateral PCC were detected in patients with obstructive sleep apnea;Citation47 increases in regional homogeneity in the PCC and lingual gyrus were found in high-altitude residents;Citation48 impairment of functional connectivity in PCC was detected in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis.Citation49 Our previous study had shown a marked decrease in white matter fractional anisotropy in the right lingual gyrus, decreases in the density of GM in the left caudate nucleus and left precentral gyrus, and decrease in the volume of GM in the right PCC of patients with COPD,Citation31,Citation50 suggesting that the impairments of white matter fiber integrity and GM structure could contribute to reduced neuronal activity. Previous multimodal neuroimaging studies have shed light on this function–structure association underlining cognition, aging, disease, and behavior.Citation51

The PCC and lingual gyrus have direct anatomical connectivity with the visual striate cortices.Citation52 The PCC lies in the path of the parieto-medial temporal visual stream, which provides spatial information to the medial temporal lobe.Citation53 It is activated by visual perception, attention, and motion.Citation54–Citation56 In addition, the PCC, connected with the inferior parietal cortex and lateral and medial superior frontal lobes, constitutes the attention networkCitation57 and visual search network.Citation58 These two networks were activated by visuoconstructive testCitation59 and visual attention task.Citation60 An animal study showed that a lesion in the PCC produced impairment in visual discrimination learning.Citation61 Decrease of resting-state functional connectivity in the PCC was exhibited in high myopia.Citation62

The lingual gyrus is a part of the occipitotemporal pathway that is engaged in object discriminationCitation63 and drawing.Citation64 The bilateral lingual gyri were activated by visuospatial navigation,Citation65 angle discrimination task,Citation66 and tactile-guided draw.Citation67 Volume of GM in the right lingual cortex has been proven to have a positive correlation with visual reproduction,Citation68 and atrophy of GM in this area was associated with visual hallucination.Citation69 Early clinicopathologic study of superior altitudinal hemianopia revealed the lingual gyrus was related to visual processing.Citation70

The limitation of our present study is that the drugs used for COPD therapy could have neurological effects. However, up to now, there are no definite evidences showing a deleterious effect of these drugs on the brain.Citation71

Conclusion

Our present study revealed abnormal spontaneous functional activity in the brain in patients with COPD, which could be the combined effect of hypoxia, hypercapnia, and inflammation. The changed regional spontaneous neuronal activity may be related to deficit in visual cognition.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of the People’s Republic of China (Project Nos 81171324; 81471630) and national key project (2012CB518200).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SadaghianiSKleinschmidtAFunctional interactions between intrinsic brain activity and behaviorNeuroimage20138037938623643921

- RomanoSAPietriTPérez-SchusterVJouaryAHaudrechyMSumbreGSpontaneous neuronal network dynamics reveal circuit’s functional adaptations for behaviorNeuron20158551070108525704948

- TanAYSpatial diversity of spontaneous activity in the cortexFront Neural Circuits201594826441547

- VisintinEDe PanfilisCAntonucciCCapecciCMarchesiCSambataroFParsing the intrinsic networks underlying attention: a resting state studyBehav Brain Res201527831532225311282

- FoxMDRaichleMESpontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imagingNat Rev Neurosci20078970071117704812

- BiswalBYetkinFZHaughtonVMHydeJSFunctional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRIMagn Reson Med19953445375418524021

- ZangYFHeYZhuCZAltered baseline brain activity in children with ADHD revealed by resting-state functional MRIBrain Dev2007292839116919409

- HoptmanMJZuoXNButlerPDAmplitude of low-frequency oscillations in schizophrenia: a resting state fMRI studySchizophr Res20101171132019854028

- HuangXQLuiSDengWLocalization of cerebral functional deficits in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia using resting-state fMRINeuroimage20104942901290619963069

- YinYLiLJinCAbnormal baseline brain activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging studyNeurosci Lett2011498318518921376785

- QiRLiuCKeJIntrinsic brain abnormalities in irritable bowel syndrome and effect of anxiety and depressionBrain Imaging Behav Epub20151110

- ZhouYWangZZuoXNHyper-coupling between working memory task-evoked activations and amplitude of spontaneous fluctuations in first-episode schizophreniaSchizophr Res20141591808925132644

- GaoLBaiLZhangYFrequency-dependent changes of local resting oscillations in sleep-deprived brainPLoS One2015103e012032325798918

- FryerSLRoachBJFordJMRelating intrinsic low-frequency BOLD cortical oscillations to cognition in schizophreniaNeuropsychopharmacology201540122705271425944410

- HuangJBaiFYangXChenCBaoXZhangYIdentifying brain functional alterations in postmenopausal women with cognitive impairmentMaturitas201581337137626037032

- RaichleMENeuroscience. The brain’s dark energyScience200631458031249125017124311

- WatanabeTHiroseSWadaHEnergy landscapes of resting-state brain networksFront Neuroinform201481224611044

- TeppemaLJDahanAThe ventilatory response to hypoxia in mammals: mechanisms, measurement, and analysisPhysiol Rev201090267575420393196

- FukushiITakedaKYokotaSEffects of arundic acid, an astrocytic modulator, on the cerebral and respiratory functions in severe hypoxiaRespir Physiol Neurobiol2016226242926592145

- PenaFRamirezJMHypoxia-induced changes in neuronal network propertiesMol Neurobiol200532325128316385141

- MukandalaGTynanRLaniganSO’ConnorJJThe effects of hypoxia and inflammation on synaptic signaling in the CNSBrain Sci201661E626901230

- RostrupELarssonHBBornAPKnudsenGMPaulsonOBChanges in BOLD and ADC weighted imaging in acute hypoxia during sea-level and altitude adapted statesNeuroimage200528494795516095921

- SicardKMDuongTQEffects of hypoxia, hyperoxia, and hypercapnia on baseline and stimulus-evoked BOLD, CBF, and CMRO2 in spontaneously breathing animalsNeuroimage200525385085815808985

- GavelloDRojo-RuizJMarcantoniAFranchinoCCarboneECarabelliVLeptin counteracts the hypoxia-induced inhibition of spontaneously firing hippocampal neurons: a microelectrode array studyPLoS One201277e4153022848520

- SumiyoshiASuzukiHShimokawaHKawashimaRNeurovascular uncoupling under mild hypoxic hypoxia: an EEG-fMRI study in ratsJ Cereb Blood Flow Metab201232101853185822828997

- GoodallSTwomeyRAmannMAcute and chronic hypoxia: implications for cerebral function and exercise toleranceFatigue201422739225593787

- DoddJWChungAWvan den BroekMDBarrickTRCharltonRAJonesPWBrain structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multimodal cranial magnetic resonance imaging studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186324024522652026

- ZuoXNDi MartinoAKellyCThe oscillating brain: complex and reliableNeuroimage20104921432144519782143

- ColeDMSmithSMBeckmannCFAdvances and pitfalls in the analysis and interpretation of resting-state FMRI dataFront Syst Neurosci20104820407579

- GongYXManual for the Wechsler Memory Scale-RevisedChangsha, Hunan, ChinaHunan Medical University1989

- ZhangHWangXLinJGrey and white matter abnormalities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case-control studyBMJ Open201222e000844

- FowlerJCAdenosine antagonists delay hypoxia-induced depression of neuronal activity in hippocampal brain sliceBrain Res198949023783842765871

- NohJKohYHChungJMAttenuated effects of Neu2000 on hypoxia-induced synaptic activities in a rat hippocampusArch Pharm Res201437223223823733585

- ThakurNBlancPDJulianLJCOPD and cognitive impairment: the role of hypoxemia and oxygen therapyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010526326920856825

- Dal NegroRWBonadimanLBricoloFPTognellaSTurcoPCognitive dysfunction in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with or without Long-Term Oxygen Therapy (LTOT)Multidiscip Respir Med20151011725932326

- JohnWMWangSCResponse of medullary respiratory neurons to hypercapnia and isocapnic hypoxiaJ Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol1977435812821591474

- LehmenkühlerABingmannDSpeckmannEJNeuronal and glial responses to hypoxia and hypercapniaBiomed Biochim Acta1989482–3S155S1602499319

- MarshallOUhJLurieDLuHMilhamMPGeYThe influence of mild carbon dioxide on brain functional homotopy using resting-state fMRIHum Brain Mapp201536103912392126138728

- CorfieldDRMurphyKJosephsOAdamsLTurnerRDoes hypercapnia-induced cerebral vasodilation modulate the hemodynamic response to neural activation?NeuroImage2001136 Pt 11207121111352626

- BhogalAASieroJCFisherJAInvestigating the non-linearity of the BOLD cerebrovascular reactivity response to targeted hypo/hypercapnia at 7TNeuroimage20149829630524830840

- SethiSMahlerDAMarcusPOwenCAYawnBRennardSInflammation in COPD: implications for managementAm J Med2012125121162117023164484

- GanWQManSFSenthilselvanASinDDAssociation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysisThorax200459757458015223864

- O’ConnorMFIrwinMRWellischDKWhen grief heats up: pro-inflammatory cytokines predict regional brain activationNeuroimage200947389189619481155

- InagakiTKMuscatellKAIrwinMRColeSWEisenbergerNIInflammation selectively enhances amygdala activity to socially threatening imagesNeuroimage20125943222322622079507

- MuscatellKAMoieniMInagakiTKExposure to an inflammatory challenge enhances neural sensitivity to negative and positive social feedbackBrain Behav Immun Epub2016328

- McKayLCEvansKCFrackowiakRSCorfieldDRNeural correlates of voluntary breathing in humansJ Appl Physiol (1985)20039531170117812754178

- TothMFaludiBWackermannJCzopfJKondakorICharacteristic changes in brain electrical activity due to chronic hypoxia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS): a combined EEG study using LORETA and omega complexityBrain Topogr200922318519019711180

- YanXZhangJGongQWengXProlonged high-altitude residence impacts verbal working memory: an fMRI studyExp Brain Res2011208343744521107542

- ChengHLLinCJSoongBWImpairments in cognitive function and brain connectivity in severe asymptomatic carotid stenosisStroke201243102567257322935402

- ZhangHWangXLinJReduced regional gray matter volume in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a voxel-based morphometry studyAJNR Am J Neuroradiol201334233433922859277

- SuiJHusterRYuQSegallJMCalhounVDFunction-structure associations of the brain: evidence from multimodal connectivity and covariance studiesNeuroimage2014102Pt 1112324084066

- WhittingstallKBernierMHoudeJCFortinDDescoteauxMStructural network underlying visuospatial imagery in humansCortex201456859823514930

- KravitzDJSaleemKSBakerCIMishkinMA new neural framework for visuospatial processingNat Rev Neurosci201112421723021415848

- AntalABaudewigJPaulusWDechentPThe posterior cingulate cortex and planum temporale/parietal operculum are activated by coherent visual motionVis Neurosci2008251172618282307

- FischerEBülthoffHHLogothetisNKBartelsAVisual motion responses in the posterior cingulate sulcus: a comparison to V5/MT and MSTCereb Cortex201222486587621709176

- LeechRSharpDJThe role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and diseaseBrain2014137Pt 1123223869106

- HopfingerJBBuonocoreMHMangunGRThe neural mechanisms of top-down attentional controlNat Neurosci20003328429110700262

- PollmannSEštočinováJSommerSChelazziLZinkeWNeural structures involved in visual search guidance by reward-enhanced contextual cueing of the target locationNeuroimage2016124Pt A88789726427645

- FörsterSTeipelSZachCFDG-PET mapping the brain substrates of visuo-constructive processing in Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Psychiatr Res201044746246919875130

- VosselSWeidnerRMoosKFinkGRIndividual attentional selection capacities are reflected in interhemispheric connectivity of the parietal cortexNeuroimage201612914815826827815

- BusseyTJMuirJLEverittBJRobbinsTWDissociable effects of anterior and posterior cingulate cortex lesions on the acquisition of a conditional visual discrimination: facilitation of early learning vs impairment of late learningBehav Brain Res199682145569021069

- ZhaiLLiQWangTAltered functional connectivity density in high myopiaBehav Brain Res2016303859226808608

- MishkinMUngerleiderLGMackoKAObject vision and spatial vision: two cortical pathwaysTrends Neurosci1983610414417

- OgawaKInuiTThe role of the posterior parietal cortex in drawing by copyingNeuropsychologia20094741013102219027762

- GrönGWunderlichAPSpitzerMTomczakRRiepeMWBrain activation during human navigation: gender-different neural networks as substrate of performanceNat Neurosci20003440440810725932

- PrvulovicDHublDSackATFunctional imaging of visuospatial processing in Alzheimer’s diseaseNeuroimage20021731403141412414280

- LikovaLTDrawing in the blind and the sighted as a probe of cortical reorganizationRogowitzBEPappasTNHuman Vision and Electronic Imaging Proc SPIE2010814

- CheeMWChenKHZhengHCognitive function and brain structure correlations in healthy elderly East AsiansNeuroimage200946125726919457386

- GoldmanJGStebbinsGTDinhVVisuoperceptive region atrophy independent of cognitive status in patients with Parkinson’s disease with hallucinationsBrain2014137Pt 384985924480486

- BogousslavskyJMiklossyJDeruazJPAssalGRegliFLingual and fusiform gyri in visual processing: a clinico-pathologic study of superior altitudinal hemianopiaJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19875056076143585386

- OwensMYWallaceKLMamoonNWyatt-AshmeadJBennettWAAbsence of neurotoxicity with medicinal grade terbutaline in the rat modelReprod Toxicol201131444745321262341