Abstract

Background

COPD affects millions of people worldwide. Poor treatment adherence contributes to increased symptom severity, morbidity and mortality. This study was designed to investigate adherence to COPD treatment in Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

Methods

An observational, cross-sectional study in adult COPD patients in Turkey and Saudi Arabia. Through physician-led interviews, data were collected on sociodemographics and disease history, including the impact of COPD on health status using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT); quality of life, using the EuroQol Five-Dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D); and anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Treatment adherence was measured using the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). Multivariate logistic regression analysis examined the predictors of non-adherence and the impact of adherence on symptom severity.

Results

Four hundred and five COPD patients participated: 199 in Turkey and 206 in Saudi Arabia. Overall, 49.2% reported low adherence (MMAS-8 <6). Of those, 74.7% reported high disease impact (CAT >15) compared to 58.4% reporting medium/high adherence (p=0.0008). Patients with low adherence reported a lower mean 3-level EQ-5D utility value (0.54±0.35) compared to those with medium/high adherence (0.64±0.30; p<0.0001). Depression with HADS score 8–10 or >10 was associated with lower adherence (OR 2.50 [95% CI: 1.43–4.39] and 2.43 [95% CI: 1.39–4.25], respectively; p=0.0008). Being a high school/college graduate was associated with better adherence compared with no high school (OR 0.57 [95% CI: 0.33–0.98] and 0.38 [95% CI: 0.15–1.00], respectively; p=0.0310). After adjusting for age, gender, and country, a significant association between treatment adherence (MMAS-8 score ≥6) and lower disease impact (CAT ≤15) was observed (OR 0.56 [95% CI: 0.33–0.95]; p=0.0314).

Conclusion

Adherence to COPD treatment is poor in Turkey and Saudi Arabia. Non-adherence to treatment is associated with higher disease impact and reduced quality of life. Depression, age, and level of education were independent determinants of adherence.

Introduction

COPD is a major contributor to chronic morbidity and mortality. It is estimated to have caused almost 3.2 million deaths globally in 2015 (equating to ~6% of all deaths)Citation1 and is projected to be the third leading cause of death in middle-income countries by 2030.Citation2 COPD can be a debilitating illness, which has a huge impact on quality of life. It was estimated to be responsible for 63.8 million disability-adjusted life years in 2015.Citation3 Although not curable, it is treatable and symptom management is crucial.

As with other chronic diseases, successful symptom management depends on many factors, one of which is patient adherence to the treatment regimen, yet studies suggest that many patients with chronic diseases do not use their medications as recommended. For example, a study carried out in Italy found that only 39.3% of outpatients with chronic conditions were adherent to their medication over the 4 weeks preceding their physician visit.Citation4 A separate study in Saudi Arabia investigating medication use for chronic conditions reported that only 32.7% of medications were used exactly as prescribed.Citation5 Reported adherence to COPD therapy specifically is poor. A recent study in Copenhagen reported the levels of adherence among COPD patients as ranging from 25% to 68% depending on the treatment regimen,Citation6 and in a study in the USA, 58% of patients were found to be non-adherent to their COPD medications.Citation7

There are limited studies that have examined adherence to COPD therapy specifically in the Middle East and Turkey. The available data come from small studies often carried out in a single hospital and the study designs are diverse.Citation8–Citation10 To address this unmet need, the ADCARE study was conducted. The primary objective of the study was to estimate the adherence to treatment in asthma and COPD in Turkey and Saudi Arabia under real-world care conditions using a standardized protocol. The secondary objectives were to collect data on disease characteristics, disease management, and health care resource utilization; to assess the main risk factors for non-adherence; and to analyze the relationship between adherence to treatment and asthma control/impact of COPD on health status. The results presented here will focus only on COPD.

Methods

Study overview

The ADCARE study is an observational, cross-sectional, multicenter study conducted in adult patients with either COPD or asthma in Turkey and Saudi Arabia. The study was conducted between September 2014 and August 2016.

A steering committee of experts specializing in COPD and asthma, in addition to appropriate representatives from the sponsor project team, was established to provide input on the study design and the scientific operation of the study, to review the data analyses, and to provide recommendations on publication strategy. Data were collected by contract research organizations (CROs) in Turkey (ZeinCRO) and Saudi Arabia (Clinart). Data management and analysis was performed by MS Health (Morocco).

Feasibility study

Prior to initiating the main study, a feasibility study was performed in each participating country in order to investigate the most appropriate method for recruiting patients and to assess the acceptability of the case report form (CRF) and the method of data collection.

Recruitment of investigators

In each country, specialists in respiratory disease (pulmonologists, internists, or other respiratory/allergy specialists) were approached for participation in the study. Physicians were randomly selected from established hospitals treating COPD patients. The eligible physicians had to have a track record in conducting observational studies and have awareness of Good Clinical Practice (GCP), in addition to the availability of structured patient records. Physicians were recruited from multiple regions across the 2 countries. In Saudi Arabia, physicians from the Central, Western, Southern, and Eastern regions participated. In Turkey, physicians from the Central Anatolia, Aegean, Marmara, Mediterranean, Black Sea, and South Eastern Anatolia regions participated. Ensuring physician representation across several regions of the participating countries enabled a representative patient sample from across the country to be recruited.

At first contact, a short overview of the study was provided to the physician, and written agreement to participate as an investigator was obtained. All physicians were trained in correct CRF completion and instructions for patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and received training on reporting adverse events, prior to patient enrolment at the site.

Recruitment of patients

A sample size of 200 COPD patients was targeted from each country in order to estimate the adherence with a precision (95% CI) of ±7.5% and a statistical power (1-β) of 80%. The total number of COPD patients targeted to take part in the study was 400.

During a 3-month inclusion period, participating investigators recruited all successive patients attending a spontaneous or previously planned consultation with their doctors and who fulfilled the eligibility criteria, until the prespecified target of 400 patients was reached. All subjects who 1) were aged ≥40; 2) had a documented COPD diagnosis ≥1 year; 3) had been prescribed at least 1 COPD maintenance medication by one of the participating investigators in the 3 months prior to inclusion (including but not limited to inhaled corticosteroids [ICSs], long-acting beta agonist [LABA], long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA], ICS/LABA, ICS+LAMA, ICS/LABA+LAMA, and/or phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibitors or any combination of these); 4) were informed of the study objectives and provided their written consent, were eligible unless the prespecified quota had already been filled. If the subject was not eligible, this was documented. Reasons for ineligibility were severe psychiatric illness or other disease that could compromise participation in the study or current participation in a clinical trial or cohort study.

Data collection by the investigating physician

During the patient visit, once written informed consent to participate was obtained, data were collected on sociodemographics (such as age, gender, weight, education level, and smoking status), comorbidities, the patient’s disease history related to COPD, disease management, and COPD-related health care resource utilization. Some of these data were ascertained retrospectively from the patient’s medical records.

PROs

The impact of COPD on health status was assessed using the 8-item COPD Assessment Test (CAT).Citation11 In this study, a CAT score of <10 equates to low impact, 10–15 signifies medium impact, and >15 denotes high impact. The level of breathlessness experienced by the patient was assessed via the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea scale;Citation12 this is scored on a single scale from 1 (“I only get breathless with strenuous exercise”) to 5 (“I’m too breathless to leave the house”). Quality of life was assessed using the 3-level EuroQol Five-Dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L) – a self-report tool comprising a 5-item health status measure from which a utility value is calculated and a EuroQol Visual Analog rating Scale (EQ-VAS) (© EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D™ is a trade mark of the EuroQol Research Foundation).Citation13,Citation57 On the advice of the EuroQol Research Foundation, the EQ-5D-3L utility values presented were calculated based on the UK value sets, in the absence of country-specific data for Turkey and Saudi Arabia. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to assess the levels of anxiety and depression experienced by the patient.Citation14 A score of <8 represented a patient who was not anxious/depressed; a score between 8 and 10 represented a patient who was questionably anxious/depressed; and a score >10 indicated a patient who was anxious/depressed.

Adherence to treatment was measured by the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8), an 8-item self-report questionnaire which has been validated and used widely in many disease areas.Citation15–Citation17 Question 1 asks, “Do you sometimes forget to take your medication?”; question 2 asks, “People sometimes miss taking their medications for reasons other than forgetting. Thinking over the past 2 weeks, were there any days when you did not take your medication?”; question 3 asks, “Have you ever cut back or stopped taking your medication without telling your doctor, because you felt worse when you took it?”; question 4 asks, “When you travel or leave home, do you sometimes forget to bring along your medication?”; question 5 asks, “Did you take your medication yesterday?”; question 6 asks, “When you feel like your condition is under control, do you sometimes stop taking your medication?”; question 7 asks, “Taking medication every day is a real inconvenience for some people. Do you ever feel hassled about sticking to your treatment plan?”; question 8 asks, “How often do you have difficulty remembering to take all your medications?”. The responses for the items are yes/no except for the last item, which is scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The score was calculated according to the author’s instructions, and the possible score ranges from 0.0 to 8.0. A score of <6.0 indicated low adherence to treatment, while scores between 6.0 and <8.0, and 8.0 were categorized as medium and high adherence, respectively.Citation17 Written permission was obtained from the copyright owners of the MMAS-8 questionnaire for any excerpts from copyrighted works that are included and the sources have been credited in the article.

Validated, local language versions (Arabic and Turkish) of the questionnaires were used in each country. In Saudi Arabia, a proportion of questionnaires were completed in English at the patient’s request.

Statistical analysis

Categorical and ordinal variables are presented as frequency and counts. Continuous variables are presented as mean values with standard deviation. Univariate and multivariate analysis were used to identify the principal risk factors associated with poor adherence. Potential associations were tested using the χ2-test, Fisher’s exact test, or the Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. The variables reported on the physician and patient questionnaires were assessed for association with non-adherence. In the first step, each variable was evaluated independently in a univariate analysis. All variables with a p-value of <0.20Citation18 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multiple logistic regression analysis in which variables were retained in the model using a backward selection in order to determine the variables that were associated with non-adherence at the probability level of 0.05. A final multivariate analysis was conducted to generate ORs. The relationship between the impact of COPD on health status and adherence to treatment was also assessed via multiple logistic regression analysis adjusting for age, gender, and country as potential confounding factors. Two-sided tests were used throughout and a probability level of 0.05 considered as statistically significant unless otherwise specified. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practices and ICH GCP as this applies to observational research. In Turkey, the ADCARE study was approved by Gazi University Ethics Committee (Gazi Üniversitesi Klinik Araştırmalar Etik Kurulu), in line with the country practice for multicentered studies where a single ethics committee approval obtained from the coordinator site’s ethics committee is sufficient. In Saudi Arabia, the study was approved by the following ethics committees: Institutional Review Board, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center; Clinical Research Committee and Research Ethics Committee at King Faisal Specialist Hospital; Institutional Review Board of the Central Region; King Fahad Medical City Institutional Review Board; King Khaled University Hospital Institutional Review Board; Air Base Dammam Research and Ethics Committee; Research Ethics Committee, Unit of Biomedical Ethics-King Abdelaziz University; Institutional Review Board at King Fahd Military Hospital; Research Ethics Committee in King Khalid University; and King Fahad Medical City Institutional Review Board, Medina. Subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the study. All data collected were kept confidential and anonymous. Participating subjects did not receive any financial compensation for their participation in the study.

Results

Study recruitment

In Saudi Arabia, a total of 22 physicians were invited to participate. Of these, 8 refused to take part, 2 did not respond, 1 did not sign the study contract, and 1 dropped out. Therefore, 10 physicians participated in the study as investigators, who recruited a mean number of 17 COPD patients per site.

In Turkey, a total of 35 physicians were invited to participate. Four sites were not initiated or dropped out. Therefore, 31 physicians participated in the study as investigators, who recruited a mean number of 6 COPD patients per site.

Study population

A total of 405 patients with COPD agreed to participate in the study. This population was evenly distributed between Turkey (n=199) and Saudi Arabia (n=206). Demographics of the overall study population and the individual countries studied are shown in . The majority of respondents were men (81.5%; n=330), >60 years of age (72.1%; n=292), either past or current smokers (80.7%; n=327), overweight or obese (62.5%; n=248), and reported at least 1 comorbidity (70.6%; n=286).

Table 1 Demographics of the study population

Disease characteristics

Overall, the mean age at symptom onset was 52.3 years of age and the mean disease duration was 10 years. Approximately half (52.5%; n=209) of all patients reported having had an exacerbation in the last 12 months, and 43.7% (n=164) reported having used oxygen therapy in the last 6 months. In addition, 66.6% (n=261) of patients reported high disease impact (CAT >15), and the vast majority of patients (91.1%; n=356) reported an MRC score of >1.

In Saudi Arabia, patients appear to present with more severe disease compared with Turkey. A higher percentage of patients (61.3%; n=122) in Saudi Arabia reported having had an exacerbation in the last 12 months compared with Turkey (43.7%; n=87; p=0.0004), and a higher percentage of patients reported a CAT score of >15 in Saudi Arabia (77.2%; n=152) compared with Turkey (55.9%; n=109; p<0.0001).

The overall EQ-5D-3L utility score reported by the patients was 0.59, and the EQ-VAS score was 65.2. Less than half of the overall study population were classed as anxious (42.9%; n=168) and approximately half were classed as depressed (54.1%; n=211; HADS anxiety or depression score ≥8). These results are presented in .

Table 2 Disease characteristics

Disease management

Overall, the majority of patients (68.9%; n=270) had undergone a lung function test in the last 6 months. Of those who did undergo the examination, 58.3% (n=151) had a last value of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) >50%, and 48.1% (n=124) had a last value of forced vital capacity (FVC) >70%.

At a country level, almost all patients had undergone a lung function test in Turkey (91.8%; n=178) compared with less than half of the patients in Saudi Arabia (46.5%; n=92; p<0.0001). In addition, only 52% of patients in Turkey who had a lung function test in the last 6 months had an FEV1 value of >50% compared to 71.4% of those in Saudi Arabia (p=0.0041). These results are presented in .

Table 3 Disease management

Adherence to COPD treatment

Overall, 49.2% (n=190) of patients reported low adherence to treatment (MMAS-8 <6) and the mean Morisky score was 5.4. The mean MMAS-8 score was significantly higher in Turkey (6.2) compared with Saudi Arabia (4.6; p<0.0001). A higher proportion of patients reported low treatment adherence in Saudi Arabia (64.2%; n=122) compared with Turkey (34.7%; n=68; p<0.0001). Overall, only 20% (n=77) of patients reported high treatment adherence (MMAS-8=8), and the proportion of highly adherent patients in Turkey (28.1%; n=55) was more than double that of Saudi Arabia (11.6%; n=22). These results are presented in .

Table 4 Adherence to treatment

Overall, 74.7% (n=139) of patients who reported low adherence to treatment had a CAT score of >15, compared with only 58.4% (n=111) of those who reported medium/high treatment adherence (p=0.0008). In addition, those patients who reported low treatment adherence reported a lower EQ-5D-3L utility value (0.54) compared with those with medium/high adherence (0.64; p<0.0001). There was no significant difference observed in reported EQ-VAS scores between adherence classes. These data are presented in .

Table 5 Association between adherence to treatment, impact of COPD on health status, and quality of life

Predictors of non-adherence

The univariate analysis showed that the following variables were found to have a significant (p<0.20) association with low treatment adherence (defined as an MMAS-8 score of <6): gender, country, age, educational level, the presence of comorbidities, anxiety, depression, MRC score, the number of exacerbations, and last value of FEV1.

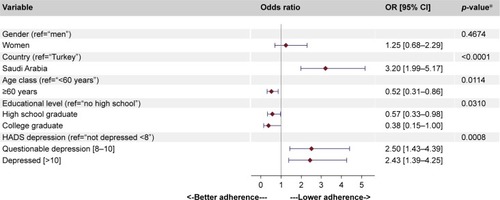

More detailed investigation using a backward step-wise multivariate regression analysis revealed that, of those variables, living in Saudi Arabia was associated with lower treatment adherence (OR 3.20; p=0.0001) compared with Turkey. In addition, HADS depression 8–10 or >10 was also associated with lower treatment adherence (OR 2.50 and 2.43, respectively; p=0.0008). Higher education (high school or college graduate) was associated with better treatment adherence compared to not graduating high school (OR 0.57 and 0.38, respectively; p=0.0310), and being ≥60 years of age was also associated with better treatment adherence (OR 0.52) compared to <60 years of age (p=0.0114). These results are presented in .

Figure 1 Multivariate analysis: predictors of non-adherence to COPD treatment.

Abbreviations: HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MMAS-8, 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.

Impact of adherence to treatment on symptom severity

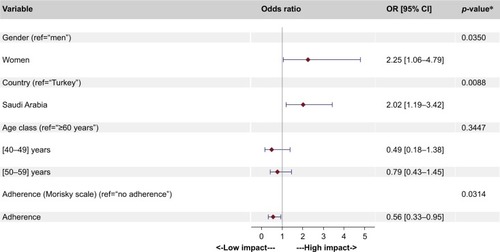

After adjusting for age, gender, and country, a significant association (p=0.0314) between patients who were adherent to treatment (defined as an MMAS-8 score of ≥6) and decreased disease impact (defined as CAT ≤15) was observed (OR 0.56). These results are presented in .

Figure 2 Association between treatment adherence and CAT score.

Abbreviation: CAT, COPD Assessment Test.

Discussion

This study marks the first time that COPD treatment adherence under real-world care conditions has been measured in Turkey and Saudi Arabia using a standardized questionnaire across multiple sites. The results demonstrate an association between poor treatment adherence, increased disease impact, and reduced quality of life, and show a correlation between depression and lower treatment adherence and between older age and higher education with better treatment adherence. It should be noted that the observation of an association between adherence to treatment, depression, quality of life, and symptom severity makes no assumptions about causality.

Analysis of the demographics of the study population revealed the majority of COPD patients to be male and either current or former smokers. Smoking is considered to be a major risk factor for COPDCitation19 and smoking rates in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are known to be high. Data from the BREATHE study reported as many as 39.5% of respondents in Turkey and 27.9% of respondents in Saudi Arabia were smokers.Citation20 In addition, smoking rates in men still far exceed those in women in the MENA region, which may be a factor influencing the higher proportion of men in the study population. Data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey Atlas published in 2015 reports the current smoking prevalence in Turkey in adults over the age of 15 as 48% in men and only 15% in women.Citation21 This gender gap was also illustrated in the BREATHE study, which reported that, in Saudi Arabia, 38.7% of men were smokers compared with only 7.4% of women, and in Turkey, 61% of men were smokers compared with only 23.5% of women.Citation20 Interestingly in this study, ~30% of patients in Saudi Arabia stated they were non-smokers. Since smoking is recognized as a major risk factor for COPD, this percentage is high. However, reporting of smoking in Saudi Arabia may be more difficult culturally than in Turkey, especially among women, who represent 25% of the ADCARE study population in Saudi Arabia, and those patients who reported as non-smokers may have been exposed to passive smoking. In addition, smoking is not the only risk factor for COPD; exposure to biomass fuels and smoke from wood burning has also been associated with COPD,Citation22 which is common in Saudi Arabia. Indoor exposure to smoke from open wood fires or burning of biomass fuels has previously been found to be a risk factor for COPD among Saudi women.Citation23 COPD has also been independently associated with multiple conditions such as coronary heart diseaseCitation24 and lung cancer.Citation25 Therefore, it is not surprising that given the age of the subjects and the high prevalence of smoking, which is itself known to be a risk factor for many of these diseases,Citation26 the majority of the study population reported at least 1 comorbidity.

Recent studies in chronic diseasesCitation4 and COPD specificallyCitation7 report poor levels of medication adherence. In line with this, approximately half (49.2%) of COPD patients in this study reported low treatment adherence. Adherence was measured using the MMAS-8 – a scale that has been used widely to investigate adherence to medication in many disease areas including asthmaCitation27–Citation29 and COPD,Citation30–Citation32 where it has been used to investigate adherence to inhaled medications.

In Turkey, there are very few studies investigating COPD treatment adherence, and most of those that have been published are single-center studiesCitation8–Citation10 and focus on parameters such as inhaler technique.Citation33 One Turkish study carried out in a single center, with a sample size of 59 patients, was designed principally to validate the Turkish version of the MMAS-8 questionnaire and reported that 46.4% of COPD patients had low adherence to treatment,Citation9 which is comparable to the findings presented here, where 34.7% of COPD patients reported low adherence. Further research is needed to gain a better understanding of the levels of treatment adherence in COPD patients in these 2 countries, and repeating this study at different time points in the future would provide insights into this evolving problem.

Analysis of the results presented here shows that patients living in Saudi Arabia are more likely to be non-adherent to treatment than those in Turkey. The Ministry of Health (MOH) in Turkey has prioritized chronic respiratory diseases in their national health programs. The National Control Program and Action Plan in Chronic Airway Diseases was put in place in 2009 through partnership with the World Health Organization Global Alliance against Respiratory Disease, with COPD being of special importance.Citation34 Data from the 2015 Global of Burden of Disease study report COPD as the seventh leading cause of years of life lost in Turkey. In contrast, in Saudi Arabia, COPD did not feature in the top 10 diseases.Citation1 The initiative from the MOH in Turkey to promote the awareness of COPD in the country and reinforce the treatment guidelines could be a contributing factor to the higher proportion of patients who are adherent to treatment in this country. Access to health care can influence a patient’s adherence to treatment. There are a high proportion of expatriates living and working in Saudi Arabia, and the sociodemographics of this population may vary from the local population in terms of income, educational level, and access to health care. A breakdown of the local versus expatriate populations was not collected as part of the study. However, data collected on the educational level and health system coverage of the study population indicate that, in this study, access to health care is not an issue since the proportion of patients in both countries having no health system coverage is extremely low.

COPD is known to be a severely debilitating disease and has a substantially negative impact on the quality of life,Citation35 and the extent of this impact has been linked to the severity of the disease as measured by the number or severity of exacerbations,Citation36,Citation37 and lung function,Citation38 and the CAT score.Citation39 In line with this, the patients enrolled in this study experience a high impact of COPD on their health-related quality of life as demonstrated by the low EQ-5D-3L utility values and EQ-VAS scores reported.

The findings from the ADCARE study also demonstrate that patients with poor adherence to treatment have a significantly lower mean EQ-5D-3L utility value than those with medium or high adherence, indicating a correlation between adherence to treatment and quality of life. Previously published studies provide inconsistent insight into this relationship. Some studies suggest that better quality of life leads to low adherence to treatment, as a result of the patient’s perception of the benefits versus risk of taking their medication.Citation40 Other studies suggest that, in line with the findings presented here, non-adherence to the prescribed treatment regimen is correlated with a negative impact on quality of life.Citation41 Further research is needed to understand this complex relationship.

The published literature exploring a potential correlation between COPD symptom severity and adherence to treatment is complex, and comparison of data between the studies is difficult since different methodologies were used and different outcomes were measured. Data from the TORCH study reports no association between adherence to treatment and symptom severity as defined by Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage, although patients with poor adherence did have lower baseline FEV1 and increased dyspnea.Citation42 Similar findings were reported by another study investigating long-term adherence to home nebulizer use.Citation43 Other studies report no significant association between adherence and severity, measured by FEV1.Citation40 Interestingly, a recent study based on the Continuing to Confront COPD International Patient Survey data reports an association between low medication adherence (measured using the MMAS-8) and increased symptom severity (measured by CAT).Citation30 This is in line with the ADCARE data, which demonstrates that, overall, there is a greater proportion of patients reporting high disease impact (as measured by a CAT score of >15) in the low adherence group compared with those with medium or high adherence, an association that was confirmed in the multivariate regression analysis that showed that adherence to treatment was correlated with lower disease impact.

In this study, only 8.5% of patients had FEV1 <30% and only 15.5% of patients had FVC <50%, and yet nearly 50% used oxygen therapy in the previous 6 months. This suggests that the use of oxygen therapy was for breathlessness rather than as a long-term treatment for severe disease. Interestingly, despite the small proportion of patients with highly impaired lung function, two-thirds of patients reported a high impact of COPD on health status (CAT >15). This is not an unusual finding, lower FEV1 has been shown to be associated with worse health, but the correlation is low, implying that some patients may have very poor health despite mild impairment in lung function.Citation44 CAT scores can show significant impairment in health status across all COPD severities, even in patients with mild disease, regardless of whether severity was assessed by a physician or classified by GOLD stage.Citation45

Adherence to treatment for chronic diseases is a complex area. There are likely to be many factors involved that will vary depending on the patient and disease profile. Depression is known to be an important comorbidity of COPD,Citation48 which is often untreated and is associated with poorer health outcomes.Citation49 An association between depression and poor treatment adherence in chronic disease,Citation50 and specifically in respiratory diseases such as asthmaCitation51 and COPD,Citation52 has been reported in the literature. One such study was carried out in 78 patients in Turkey and showed that the presence of depressive symptoms was associated with low adherence to treatment.Citation47 These findings are in line with the data presented here describing a significant correlation between depression and non-adherence to treatment.

Overall, both higher education and older age were associated with better adherence to treatment in the ADCARE study, but further research is needed to improve the understanding of the role that these factors play in treatment adherence for COPD. There is conflicting data published on the impact of demographic variables such as age and educational level on treatment adherence. Some studies have found that subjects who are older and better educated are more likely to be adherent to treatment.Citation43,Citation53 Other studies have shown no significant association.Citation46 Some studies suggest that older age is a risk factor for non-adherence due to factors such as cognitive impairment, particularly forgetfulness and polypharmacy.Citation54 A recent study carried out in Saudi Arabia, based on the findings from a National household survey, reported that older age was associated with better treatment adherence in subjects with chronic diseases.Citation5 It has also been reported that patients with poor adherence often have insufficient understanding of their disease and its management options, and tend to rely more on natural remedies,Citation55 which could be linked to patient education. In line with this, a recent study carried out among Palestinian geriatrics living with chronic disease reported a correlation between a higher level of knowledge about the medication and improved adherence to the treatment.Citation56

ADCARE is one of the few studies addressing adherence to treatment in a real-life setting in the region, and the use of an identical study methodology in Turkey and Saudi Arabia enables pertinent comparisons to be made between the 2 countries. In addition, data on the impact of COPD on health status, quality of life, and adherence to treatment were collected using validated questionnaires (CAT, HADS, EQ-5D, MRC, and MMAS-8), which have been used widely, enabling comparison with data collected elsewhere.

Some limitations of the study should be noted. Since the study was conducted under real-world care conditions, patients visiting their physicians more often (and therefore it could be hypothesized that these patients have more severe disease) have a higher probability of being included in the study compared to those rarely seen. This may be a limitation in the generalizability of the study, although it has been shown in the multivariate analysis that the number of exacerbations (which is an indication of severity) is not associated with adherence. In addition, as is the case for all studies that require participants to recall data, there is a risk of recall bias and inaccuracy in the data collected. Furthermore, detecting poor adherence is challenging since there are many available methods to collect the data. In this study, patient self-reporting is used (the MMAS-8 questionnaire), which is the most cost-effective method but may result in an overestimate of adherence since patients frequently overreport medication adherence when completing such questionnaires. It is also noteworthy that the UK value sets were used to derive the utility values in the absence of country-specific reference values for Turkey and Saudi Arabia, on the advice of the EuroQol Group. Deriving the utility values based on country-specific value sets would be an important topic for future research.

In conclusion, the results presented here reveal that, in both Turkey and Saudi Arabia, adherence to COPD treatment is low and provides a benchmark for future studies investigating treatment adherence in these countries. The association between depression and poor adherence indicates that physicians should take into account psychological symptoms when treating COPD and consider counseling for those who are suffering. Another area for improvement is patient education, and educational level should be taken into account when treating patients with COPD to ensure patients understand the correct inhaler technique and benefits of regularly taking their medication. In addition, an association between non-adherence to treatment and higher disease impact, as well as a greater impact on the quality of life is demonstrated. Symptom management is a key aim of health care providers and policy makers, and therefore, improving adherence to treatment should be a key priority for decision-makers in order to reduce the burden of disease attributed to COPD.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Sarah Osei-Ntem, an employee of GSK, in the form of manuscript development, collating of author comments, copy editing and referencing. Data analysis support was provided by Leyla Depret-Bixio, a former employee of GSK. The authors also express their appreciation for the contributions of Ahmed Abu Al Faraj, Caglar Karakurum, Selda Özdemir, Candice Pinto, Indira Umareddy (formerly employed at GSK), Tamer Elfishawy, Raef Gouhar, Saeed Noibi, Shireen Quli Khan, Nauman Rashid, Yalcin Seyhun (GSK), Aaicha Lahlou, Sophie Abadie, Salaheddine El Khadiri, Maria José Lopez (MS Health), and the participating CROs (Clinart and ZeinCRO) in different stages of the ADCARE study. The MMAS (8-item) content, names, and trademarks are protected by the US copyright and trademark laws. Permission for use of the scale and its coding is required. A license agreement is available from Donald E Morisky, ScD, ScM, MSPH, 14725 NE 20th St Bellevue, WA 98007, USA; [email protected]. Permission to use the EQ-5D-3L was provided by the EuroQol Research Foundation (© EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D™ is a trade mark of the EuroQol Research Foundation).

Funding for this study was provided by GSK (GSK study number 200368, GSK study acronym: ADCARE).

Data availability

Editors can seek information from the corresponding author regarding whether anonymized patient level data can be made available.

Disclosure

AEH, FA, and LT are employees of and shareholders in Glaxo-SmithKline (GSK), which funded the ADCARE study. AD is a director of Foxymed, a medical communication and consultancy company, which participated in the design of the study and the interpretation of the results on behalf of GSK. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015Lancet2016388100531459154427733281

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015Lancet2016388100531603165827733283

- NapolitanoFNapolitanoPAngelilloIFMedication adherence among patients with chronic conditions in ItalyEur J Public Health2016261485226268628

- Moradi-LakehMEl BcheraouiCDaoudFMedication use for chronic health conditions among adults in Saudi Arabia: findings from a national household surveyPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf2016251738126494489

- IngebrigtsenTSMarottJLNordestgaardBGLow use and adherence to maintenance medication in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the general populationJ Gen Intern Med2015301515925245885

- KrauskopfKFedermanADKaleMSChronic obstructive pulmonary disease illness and medication beliefs are associated with medication adherenceCOPD201512215116424960306

- GulbayBEDoganRYildizOAPatients adherence to treatment and knowledge about chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseSaudi Med J20062791427142916951791

- OguzulgenIKKokturkNIsikdoganZTurkish validation study of Morisky 8-item medication adherence questionnaire (MMAS-8) in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseTuberk Toraks201462210110725038378

- OzyilmazEKokturkNTeksutGTatliciogluTUnsuspected risk factors of frequent exacerbations requiring hospital admission in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Clin Pract201367769169723758448

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD assessment testEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRGarnhamRJonesPWWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of lifeHealth Policy199016319920810109801

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand19836763613706880820

- MoriskyDEDiMatteoMRImproving the measurement of self-reported medication nonadherence: response to authorsJ Clin Epidemiol2011643255257 discussion 258–26321144706

- Krousel-WoodMIslamTWebberLSReRNMoriskyDEMuntnerPNew medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertensionAm J Manag Care2009151596619146365

- MoriskyDEAngAKrousel-WoodMWardHJPredictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient settingJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)200810534835418453793

- MinSYParkDWYunSCMajor predictors of long-term clinical outcomes after coronary revascularization in patients with unprotected left main coronary disease: analysis from the MAIN-COMPARE studyCirc Cardiovas Interv201032127133

- EisnerMDAnthonisenNCoultasDAn official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: novel risk factors and the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182569371820802169

- KhattabAJavaidAIraqiGSmoking habits in the Middle East and North Africa: results of the BREATHE studyRespir Med2012106Suppl 2S16S2423290700

- AsmaSMackayJSongSYZhaoLMortonJPalipudiKMThe GATS Atlas2015CDC FoundationAtlanta, GA

- KurmiOPSempleSSimkhadaPSmithWCAyresJGCOPD and chronic bronchitis risk of indoor air pollution from solid fuel: a systematic review and meta-analysisThorax201065322122820335290

- DossingMKhanJal-RabiahFRisk factors for chronic obstructive lung disease in Saudi ArabiaRespir Med19948875195227972976

- SinDDManSFChronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortalityProc Am Thorac Soc20052181116113462

- KiriVASorianoJVisickGFabbriLRecent trends in lung cancer and its association with COPD: an analysis using the UK GP Research DatabasePrim Care Respir J2010191576119756330

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and HealthReports of the Surgeon GeneralThe Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon GeneralAtlanta, GACenters for Disease Control and Prevention (US)2014

- ChiuKCBoonsawatWChoSHPatients’ beliefs and behaviors related to treatment adherence in patients with asthma requiring maintenance treatment in AsiaJ Asthma201451665265924580369

- GuenetteLBretonMCGregoireJPEffectiveness of an asthma integrated care program on asthma control and adherence to inhaled corticosteroidsJ Asthma201552663864525539138

- DingBSmallMDisease burden of mild asthma: findings from a cross-sectional real-world surveyAdv Ther20173451109112728391549

- MullerovaHLandisSHAisanovZHealth behaviors and their correlates among participants in the Continuing to Confront COPD International Patient SurveyInt J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis201611881890

- KhdourMRKidneyJCSmythBMMcElnayJCClinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPDBr J Clin Pharmacol200968458859819843062

- BakerCLGuptaSGorenAWillkeRJAdherence and satisfaction with oral versus other treatments among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd) in the u.s. 2012 national health and wellness surveyValue Health2013163A236A237

- AydemirYAssessment of the factors affecting the failure to use inhaler devices before and after trainingRespir Med2015109445145825771037

- YorganciogluATurktasHKalayciOThe WHO global alliance against chronic respiratory diseases in Turkey (GARD Turkey)Tuberk Toraks200957443945220037863

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerFWThe influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of comorbidityJ Clin Epidemiol200356121177118414680668

- LlorCMolinaJNaberanKCotsJMRosFMiravitllesMExacerbations worsen the quality of life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in primary healthcareInt J Clin Pract200862458559218266710

- SolemCTSunSXSudharshanLMacahiligCKatyalMGaoXExacerbation-related impairment of quality of life and work productivity in severe and very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis20138641652

- StahlELindbergAJanssonSAHealth-related quality of life is related to COPD disease severityHealth Qual Life Outcomes200535616153294

- MarvelJYuTCWoodRHigginsVSMakeBJHealth status of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by symptom levelChronic Obstruct Pulm Dis201633643652

- AghTInotaiAMeszarosAFactors associated with medication adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration201182432833421454953

- CordenZMBosleyCMReesPJCochraneGMHome nebulized therapy for patients with COPD: patient compliance with treatment and its relation to quality of lifeChest19971125127812829367468

- VestboJAndersonJACalverleyPMAdherence to inhaled therapy, mortality and hospital admission in COPDThorax2009641193994319703830

- TurnerJWrightEMendellaLAnthonisenNPredictors of patient adherence to long-term home nebulizer therapy for COPD. The IPPB Study Group. Intermittent Positive Pressure BreathingChest199510823944007634873

- JonesPWHealth status measurement in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2001561188088711641515

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWProperties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European studyEur Respir J2011381293521565915

- KhdourMRHawwaAFKidneyJCSmythBMMcElnayJCPotential risk factors for medication non-adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Eur J Clin Pharmacol201268101365137322476392

- TuranOYemezBItilOThe effects of anxiety and depression symptoms on treatment adherence in COPD patientsPrimary Health Care Res Dev2014153244251

- KunikMERoundyKVeazeyCSurprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disordersChest200512741205121115821196

- NgTPNitiMTanWCCaoZOngKCEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med20071671606717210879

- DiMatteoMRLepperHSCroghanTWDepression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherenceArchi Intern Med20001601421012107

- BenderBGRisk taking, depression, adherence, and symptom control in adolescents and young adults with asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173995395716424441

- AlbrechtJSParkYHurPAdherence to maintenance medications among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The role of depressionAnn Am Thorac Soc20161391497150427332765

- RandCSNidesMCowlesMKWiseRAConnettJLong-term metered-dose inhaler adherence in a clinical trial. The Lung Health Study Research GroupAm J Respir Crit Care Med199515225805887633711

- ShresthaRPantAShakya ShresthaSShresthaBGurungRBKarmacharyaBMA cross-sectional study of medication adherence pattern and factors affecting the adherence in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseKathmandu Univ Med J201513496470

- GeorgeJKongDCThomanRStewartKFactors associated with medication nonadherence in patients with COPDChest200512853198320416304262

- NajjarAAmroYKitanehIKnowledge and adherence to medications among palestinian geriatrics living with chronic diseases in the West Bank and East JerusalemPLoS One2015106e012924026046771

- BrooksREuroQol: the current state of playHealth Policy1996371537210158943