Abstract

Background and purpose

Chronic cough can be a dominant symptom of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), although its clinical impact remains unclear. The aim of our study was to identify phenotypic differences according to the presence of chronic cough or sputum and evaluate the impact of chronic cough on the risk of acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD).

Methods

In a nationwide COPD cohort including 1,613 COPD patients, patients with chronic cough only, those with sputum only, those with chronic bronchitis (CB), and those without cough and sputum were compared with regard to dyspnea, lung function, quality of life (QoL), and risk of AECOPD.

Results

The rates of chronic cough, chronic sputum, and both were 23.4%, 32.4%, and 18.2%, respectively. Compared with patients without chronic cough, those with chronic cough exhibited a lower forced expiratory volume in 1 second (% predicted) and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (% predicted), more frequent AECOPD, more severe dyspnea, and worse QoL. Pulmonary function, dyspnea severity, and QoL worsened in the following order: without cough or sputum, with sputum only, with cough only, and with CB. Multivariate analyses revealed chronic cough as an independent risk factor for a lower lung function, more severe dyspnea, and a poor QoL. Moreover, the risk of future AECOPD was significantly associated with chronic cough (odds ratio 1.56, 95% CI 1.08–2.24), but not with chronic sputum.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that chronic cough should be considered as an important phenotype during the determination of high-risk groups of COPD patients.

Introduction

Cough is a common symptom of chronic respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Several causes for chronic cough exist including COPD, and the concept of cough hypersensitivity syndromeCitation1 has been introduced to explain the common mechanism of chronic cough. However, characteristics of chronic cough in COPD have not been well described; it may exhibit features different from those of cough hypersensitivity syndrome-associated cough. As evidence to support this hypothesis, one study found that cough frequency in COPD patients is associated with sputum production, smoking, and airway inflammation, and that these factors may appear to be more important than the sensitivity of the cough reflex.Citation2 In this regard, sputum has been rather emphasized than cough in COPD patients, and a clinical phenotype characterized by prominent and persistent cough and sputum production for at least 3 months during each of two consecutive years has been defined as chronic bronchitis (CB). The CB phenotype is associated with worse respiratory symptoms, higher rate of acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), and worse disease impact in COPD patients.Citation3–Citation8 However, chronic cough is not always accompanied by sputum, and it can occur as single manifestation of COPD.Citation9 The clinical impact of chronic cough on COPD outcomes has not been well reported; therefore, it may be necessary to investigate how chronic cough affects COPD outcomes, including quality of life (QoL) and future risk of AECOPD, irrespective of presence or absence of sputum. The aim of our study was to identify phenotypic differences according to presence of chronic cough or sputum in COPD patients and evaluate the impact of chronic cough on the risk of future AECOPD.

Methods

Study population and data collection

We recruited patients enrolled in the KOrea COpd Subgroup Study (KOCOSS), which is an ongoing, multicenter cohort study of COPD that has included participants from 47 centers in South Korea since April 2012.Citation10 Inclusion criteria were as follows: Korean patients aged >40 years and post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity ratio of <0.7. Spirometry and 6-minute walk distance test were performed according to standard techniques.Citation11,Citation12 At the first visit, information regarding the frequency and severity of exacerbations in the past 12 months; smoking status; patient-reported education levels; medications; and comorbidities were recorded. The modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea scale (mMRC)Citation13,Citation14 scores for dyspnea severity, scores for the COPD Assessment Test (CAT),Citation15 and COPD-specific version of St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ-C)Citation16 were assessed. All data were documented in case report forms completed by physicians or trained nurses, and patients were re-evaluated at regular 6-month intervals after the initial examination. The major exclusion criteria were as follows: asthma; other obstructive lung diseases including bronchiectasis; tuberculosis-destroyed lungs; inability to complete the spirometry; myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular events within the past 3 months; pregnancy; rheumatoid disease; malignancy; irritable bowel disease; and use of steroids for conditions other than AECOPD within 8 weeks before enrollment. Patients with recent (8 weeks before screening) exacerbation or other respiratory illness (such as upper respiratory infection or pneumonia) were excluded; however, patients who recovered from an exacerbation and had been stable for more than 8 weeks were included. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the study patients. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review boards at each center, which are listed in the Supplementary material.

Definitions

COPD was defined and stratified by the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria.Citation17 KOCOSS includes following questionnaires to define CB: 1) Do you experience a cough most days, for at least 3 months per year? 2) Have you had cough for more than two consecutive years? 3) Do you produce sputum most days, for at least 3 months per year? and 4) Have you had sputum for more than two consecutive years? Chronic cough and sputum production were defined using these questions. If patient answered “yes” to question 1, then the subject was classified as having chronic cough. If patient answered “yes” to question 3, then they were classified into group with chronic sputum. If patient answered “yes” to 1 and 3, then the subject was defined as having CB. Patients who answered “I don’t know” and those who did not answer a question were excluded. AECOPD was defined as worsening of any respiratory symptom, such as increased sputum volume, purulence, and increased dyspnea, which required treatment with systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or both. Dyspnea was evaluated using the mMRC scale, which is a five-point scale with higher scores indicating more severe dyspnea.Citation13,Citation14 The health-related QoL was evaluated with CAT and SGRQ-C scores. CAT comprises eight items that are scored from 0 to 5, and higher score indicates more severe symptom.Citation15 SGRQ-C is a 14-item questionnaire that provides a total score as well as scores for the following three components: symptoms, activities, and impacts.Citation16 Total and component scores were calculated according to algorithms provided in the SGRQ-C instruction manual.Citation18

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range [IQR]), or frequency distribution (%). For between-group comparisons, Student’s t-tests or analyses of variance were used to compare continuous variables and chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables. Multivariate analyses were conducted using general linear regression. To compare the predictive power of future AECOPD in each model, area under the receiver operating characteristics curve was calculated. Data were analyzed using the STATA program (STATA 12.0 software, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A P-value of <0.05 (two-sided P-values examined) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients with chronic cough

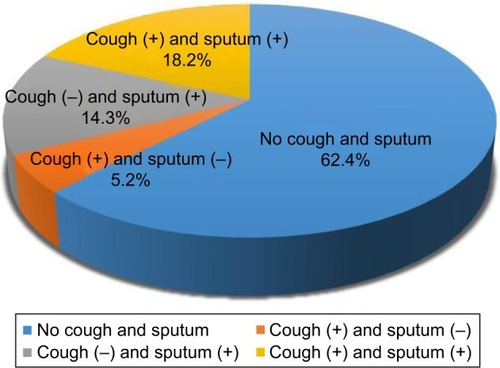

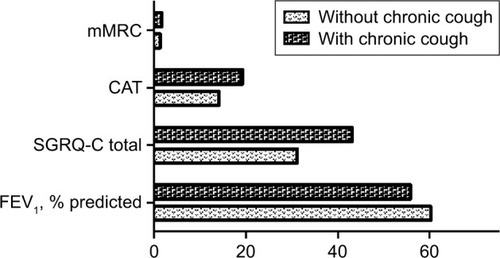

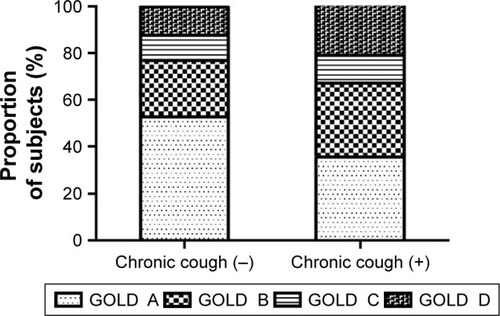

At the time of analysis, a total of 1,613 COPD patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled; 1,380 (91.6%) were men and 434 (27.1%) were current smokers (). The median age of patients was 73 years (IQR, 67–78). GOLD stage 1 (FEV1 >80%), GOLD stage 2 (FEV1, >50% to ≤80%), GOLD stage 3 (FEV1, >30% to ≤50%), and GOLD stage 4 (FEV1 ≤30%) accounted for 138, 833, 527, and 115 patients, respectively. The median follow-up duration was 12.0 (IQR, 6.0–24.0) months. The mean FEV1 was 1.58 ± 0.55 L (% predicted, 59.2 ± 18.3). In total, 377 (23.4%) patients reported chronic cough, 523 (32.4%) reported chronic sputum, and 293 (18.2%) reported both symptoms (). Compared with COPD patients without chronic cough, those with chronic cough included younger patients and more current smokers. Furthermore, patients with chronic cough experienced more frequent AECOPD and exhibited lower FEV1 (% predicted) and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO; % predicted), more severe dyspnea as assessed using mMRC scale, and poorer QoL as assessed using SGRQ-C. The results of the 6-minute walk distance test were not different between groups ( and ). When the patients were classified according to the revised GOLD 2017 criteria, those with chronic cough were more assigned to subgroups B and D, which are more symptomatic subgroups (P<0.001; ).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to the presence of chronic cough

Figure 1 Distribution of patients according to presence of chronic cough and chronic sputum production in the study cohort of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 2 Comparison of dyspnea, quality of life, and lung function between patients with COPD with chronic cough and those without chronic cough.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea scale; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; SGRQ-C, COPD-specific version of St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Figure 3 Distribution of GOLD severity stages in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with chronic cough and those without chronic cough.

The detailed clinical characteristics of COPD patients with chronic cough only, those with chronic sputum only, and those with CB are described in . COPD patients with chronic cough only were more common in current smokers compared with those without chough or sputum, similar to those with CB.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exhibiting cough, sputum production, or both

Impact of chronic cough on lung function, dyspnea, and QoL

Patients with cough only showed more severe airflow limitation during spirometry compared to patients with sputum only, which is a feature of patients with CB (). Multivariable analysis for FEV1 (% predicted) and DLCO (% predicted) were performed after adjusting for age, current smoking status, and amount of smoking; chronic cough remained a significant risk factor for a lower FEV1 and DLCO in COPD patients. However, sputum production was not found to be a significant factor for lower FEV1 and DLCO (). There was no significant interaction between cough and sputum with regard to FEV1 (P=0.33) and DLCO (P=0.78). Spirometry was followed up for 730 patients at 1 year later, and mean change of FEV1 was −0.04 ± 0.26 L. The mean changes of FEV1 were not different between groups according to presence of chronic cough (−0.04 ± 0.27 L vs −0.02 ± 0.23 L; P=0.28) or chronic sputum (−0.04 ± 0.26 L vs −0.03 ± 0.27 L; P=0.86).

Table 3 Multivariate analysis for the effects of chronic cough and chronic phlegm on the lung function, dyspnea, and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Multivariate analyses for mMRC, CAT, and SGRQ scores were performed after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, history of previous exacerbation, and baseline FEV1 (% predicted). In each model, chronic cough was independently associated with poorer mMRC (P=0.003) and CAT scores (P<0.001) as well as poorer scores for all three components of SGRQ (P<0.001; ). Although chronic sputum production was also associated with higher score for CAT (P=0.003) and symptom (P<0.001) and impact (P=0.04) components of SGRQ, the differences were not as prominent as those for chronic cough. Furthermore, chronic sputum production did not show an association with mMRC score (P=0.18) or score for activity component (P=0.32) of SGRQ (). There was no interaction between chronic cough and sputum with regard to mMRC (P=0.99), CAT (P=0.97), and SGRQ (P=0.22) scores.

Impact of chronic cough on the risk of future AECOPD

A total of 291 (18.1%) patients developed AECOPD at least once during the follow-up period. These included 15.5% patients without chronic cough or sputum, 13.3% with chronic sputum only, 17.8% with chronic cough only, and 23.1% with CB. Among them, 70 (24.1%) patients had experienced more than one exacerbation during follow-up, However, there was no significant difference in frequency of patients with multiple exacerbation according to presence of chronic cough (P=0.13) or chronic sputum (P=0.45). In univariate analyses, the risk of future AECOPD was associated with presence of chronic cough [odds ratio (OR), 1.52; P=0.004], but not with presence of chronic sputum (OR, 1.16; P=0.92). There was no interaction between chronic cough and sputum with regard to future exacerbation (P=0.16). Other factors related to future exacerbation included older age (OR, 1.04; P<0.001), previous history of exacerbation (OR, 1.95; P<0.001), and lower baseline FEV1 (% predicted; OR, 0.98; P<0.001). In multivariate analyses adjusted for age, smoking status, history of exacerbation, and baseline FEV1 (% predicted), chronic cough was independently associated with future exacerbation (OR 1.56, 95% CI, 1.08–2.24), whereas chronic sputum did not show any significant association (OR, 0.93; P=0.63; ).

Table 4 Univariate and multivariate analyses for factors contributing to future AE of chronic obstructive pulmo nary disease

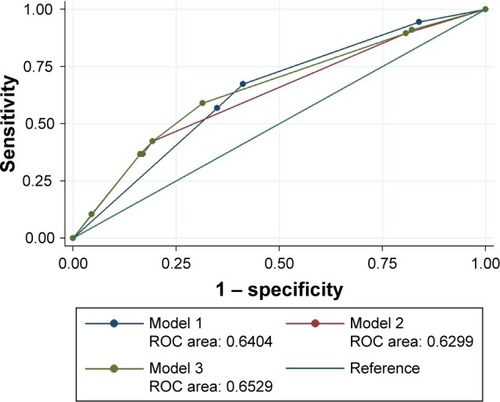

The area under the curve (AUC) for predicting future exacerbation was 0.640 when subgrouping was based on the 2011 GOLD guidelines (model 1) and 0.630 when subgrouping was based on the 2017 GOLD guidelines (model 2). When we added the variable of chronic cough while subgrouping according to the 2017 GOLD guidelines, the AUC increased to 0.653 (model 3), which was found to be the most predictive ().

Figure 4 ROC analysis for the prediction of future acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristic; GOLD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease.

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort analysis, chronic cough in COPD patients was not a simple symptom; rather, it was an independent risk factor for lower FEV1 and DLCO, more severe dyspnea, worse QoL, and future exacerbation. Interestingly, chronic cough itself showed a more significant association with disease severity and prediction of poor outcomes compared with chronic sputum, and the degree of association was similar to that in patients with CB. These findings suggest that chronic cough, and not chronic sputum, could play a role in the effects of CB in COPD patients, and that it may be important to identify patients with chronic cough irrespective of sputum to find the high-risk group.

COPD is associated with chronic inflammatory processes in the airway and parenchyma. A cough reflex can be triggered by several inflammatory or mechanical changes in the airways.Citation19 Furthermore, chronic cough was found to be associated with neutrophilic airway inflammationCitation20,Citation21 and cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha or interleukin-8.Citation21 Therefore, it could be postulated that chronic cough and COPD may share common pathophysiological pathways: airway inflammation. Thus, airway inflammation may be critical for chronic cough in COPD,Citation22 and chronic cough could be prerequisite conditions for AECOPD.

Another hypothesis for explaining the association of chronic cough with higher risk of future AECOPD may be linked to transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, particularly transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). TRPV1 may be a major molecular entity involved in the tussive response.Citation23 The pivotal function of TRPV1 in cough response is to lower the threshold to cough, which is already reduced in COPD patients.Citation24 TRP channels are associated with bronchoconstriction, airway hyper-responsiveness, and neutrophil activation. This TRP channel function may be altered in the presence of oxidative stress, inflammation, hypoxia, and mechanical stress.Citation25 Therefore, these findings may also be a clue for associating chronic cough with an increased risk of future AECOPD.

Reportedly, 3.4%–22.0% adults in the general populationCitation26–Citation35 and 14%–74% COPD patients are affected by CB.Citation3–Citation6 Moreover, some studies have reported a positive association between CB and poor COPD outcomes,Citation3–Citation8,Citation34,Citation35 whereas some have reported otherwise. Considering that the wide range of prevalence estimates for CB is because of different definitions for CB in each study, the studies should be reviewed in detail to elucidate the role of cough in the course of COPD. CB is classically defined as chronic cough and sputum production for 3 months a year for two consecutive years. However, various definitions, including one mentioning chronic sputum only, have been used in different studies, particularly in large cohorts. The prevalence of classic CB was 18.2% in the present study, while the prevalence of chronic sputum was up to 32.4%. In the Proyecto Latinoamericano de Investigación en Obstrucción Pulmonar (PLATINO) study,Citation4 CB was defined as chronic sputum production, and the findings revealed more respiratory symptom, worse lung function, and poorer QoL in CB patients. However, the number of exacerbations was not significantly different between patients with chronic sputum and those without, although the proportion of exacerbation was higher in the chronic sputum group. Even in the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints study,Citation5 which is a larger study, CB was defined as chronic sputum production, and patients with chronic sputum exhibited a poorer QoL. However, there was no significant difference in FEV1 or the number of exacerbations, even though the study included more patients with advanced COPD compared with the PLATINO study. In The Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study,Citation6 CB was defined as chronic cough and sputum production. The findings revealed more exacerbations and poorer QoL in CB patients, as expected. These inconsistent effects of CB on COPD outcomes in previous studies may be explained by the results of our analysis, which may have been affected by the proportion of patients with chronic cough in each study.

This study could make a significant contribution to clinical practice. This is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, which compares the relative effects of chronic cough and chronic sputum on COPD outcomes and identifies the role of chronic cough in COPD. The findings suggest that assessment of chronic cough is important to evaluate disease severity and predict the future prognosis of COPD patients. Furthermore, this study used longitudinal data for analysis of the risk of future AECOPD. Most previous studies were cross-sectional and compared the rates of previous exacerbations by simple interviews, which is associated with the risk of recall bias.

This study also has several potential limitations. First, the proportion of patients with cough only was relatively smaller than that of patients with CB or sputum only. Second, we could not evaluate the risk of mortality, because of the lack of sufficient cases of death in the KOCOSS cohort. In addition, in KOCOSS, other common causes of chronic cough, including postnasal drip syndrome and esophageal reflux disease, were not ruled out. Third, in a certain portion of patients in our cohort, methacholine provocation test was performed to measure bronchial hyper-responsiveness; however, in most of cases, exclusion for asthma was determined by each physician’s clinical decision, and there could be possibility of existence of patients with asthma-COPD overlap. Fourth, since severity of cough or sputum production was not measured at our questionnaire and presence of cough or sputum was not followed as primary outcome, the changes of these phenotypes could not be evaluated in our study. Finally, because individual items of CAT and SGRQ were not analyzed, sensitivity analysis excluding items regarding cough and sputum could not be performed.

Conclusion

Chronic cough itself is associated with lower FEV1 and DLCO, more severe dyspnea, and worse QoL in COPD patients. Furthermore, it is an independent risk factor for future AECOPD. The symptom of chronic cough could be considered as a unique phenotype during determination of high-risk groups of COPD patients, particularly with regard to exacerbation. Further studies about the natural course and treatment outcomes of COPD patients with chronic cough are necessary.

Supplementary material

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review boards (IRBs) at each center: Seoul National University Hospital IRB, Catholic Medical Center Central IRB, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine IRB, Severance Hospital IRB, Soon Chun Hyang University Cheonan Hospital IRB, Ajou University Hospital IRB, Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hallym University Pyeongchon Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hanyang University Guri Hospital IRB, Konkuk University Hospital IRB, Konkuk University Chungju Hospital IRB, Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center IRB, Korea University Guro Hospital IRB, Korea University Anam Hospital IRB, Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital IRB, Dong-A University Hospital IRB, Gachon University Gil Medical Center IRB, Gangnam Severance Hospital IRB, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong IRB, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital IRB, Kangwon National University Hospital IRB, Kyungpook National University Hospital IRB, Gyeongsang National University Hospital IRB, Pusan National University Hospital IRB, Soon Chun Hyang University Bucheon Hospital IRB, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital IRB, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University IRB, Asan Medical Center IRB, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital IRB, Eulji General Hospital IRB, Samsung Medical Center IRB, Ulsan University Hospital IRB, Soon Chun Hyang University Seoul Hospital IRB, Yeungnam University Hospital IRB, Ewha Womans University Mok-dong Hospital IRB, Inha University Hospital IRB, Chonbuk National University Hospital IRB, and Jeju National University Hospital IRB.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChungKFChronic “cough hypersensitivity syndrome”: a more precise label for chronic coughPulm Pharmacol Ther201124326727121292019

- ChungKFAdvances in mechanisms and management of chronic cough: The Ninth London International Cough Symposium 2016Pulm Pharmacol Ther2017472828216388

- BurgelPRNesme-MeyerPChanezPInitiatives Bronchopneumopathie Chronique Obstructive (BPCO) Scientific CommitteeCough and sputum production are associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalizations in COPD subjectsChest2009135497598219017866

- de OcaMMHalbertRJLopezMVThe chronic bronchitis phenotype in subjects with and without COPD: the PLATINO studyEur Respir J2012401283622282547

- AgustiACalverleyPMCelliBEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigatorsCharacterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Res20101112220831787

- KimVDaveyAComellasAPCOPDGene® InvestigatorsClinical and computed tomographic predictors of chronic bronchitis in COPD: a cross sectional analysis of the COPDGene studyRespir Res2014155224766722

- LindbergASawalhaSHedmanLLarssonLGLundbäckBRönmarkESubjects with COPD and productive cough have an increased risk for exacerbations and deathRespir Med20151091889525528948

- VestboJPrescottELangePAssociation of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study GroupAm J Respir Crit Care Med19961535153015358630597

- KooHKJeongILeeSWPrevalence of chronic cough and possible causes in the general population based on the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyMedicine (Baltimore)20169537e459527631208

- LeeJYChonGRRheeCKCharacteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the first visit to a pulmonary medical center in Korea: the KOrea COpd subgroup study team cohortJ Korean Med Sci201631455356027051239

- Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic SocietyAm J Respir Crit Care Med19951523110711367663792

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function LaboratoriesATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk testAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002166111111712091180

- JonesPWAdamekLNadeauGBanikNComparisons of health status scores with MRC grades in COPD: implications for the GOLD 2011 classificationEur Respir J201342364765423258783

- MahlerDAWellsCKEvaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspneaChest19889335805863342669

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- MeguroMBarleyEASpencerSJonesPWDevelopment and validation of an improved, COPD-specific version of the St. George Respiratory QuestionnaireChest2007132245646317646240

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD2017 Available from: www.goldcopd.com/guidelines-global-strategyfor-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed March 1, 2017

- JonesPWFordeYSt George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD Patients (SGRQ-C) ManualLondonSt George’s University of London2008

- ChungKFPavordIDPrevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic coughLancet200837196211364137418424325

- NiimiATorregoANicholsonAGCosioBGOatesTBChungKFNature of airway inflammation and remodeling in chronic coughJ Allergy Clin Immunol2005116356557016159625

- JatakanonALallooUGLimSChungKFBarnesPJIncreased neutrophils and cytokines, TNF-alpha and IL-8, in induced sputum of non-asthmatic patients with chronic dry coughThorax199954323423710325899

- ChungKFAdvances in mechanisms and management of chronic cough: The Ninth London International Cough Symposium 2016Pulm Pharmacol Ther2017472828216388

- GeppettiPMaterazziSNicolettiPThe transient receptor potential vanilloid 1: role in airway inflammation and diseaseEur J Pharmacol20065331–320721416464449

- WongCHMoriceAHCough threshold in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax1999541626410343635

- Abbott-BannerKPollCVerkuylJMTargeting TRP channels in airway disordersCurr Top Med Chem201313331032123506455

- von HertzenLReunanenAImpivaaraOMälkiäEAromaaAAirway obstruction in relation to symptoms in chronic respiratory disease – a nationally representative population studyRespir Med200094435636310845434

- CerveriIAccordiniSVerlatoGEuropean Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) StudyVariations in the prevalence across countries of chronic bronchitis and smoking habits in young adultsEur Respir J2001181859211510810

- JansonCChinnSJarvisDBurneyPDeterminants of cough in young adults participating in the European Community Respiratory Health SurveyEur Respir J200118464765411716169

- HuchonGJVergnenègreANeukirchFBramiGRocheNPreuxPMChronic bronchitis among French adults: high prevalence and under-diagnosisEur Respir J200220480681212412668

- LundbäckBLindbergALindströmMObstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden StudiesNot 15 but 50% of smokers develop COPD? Report from the obstructive lung disease in Northern Sweden studiesRespir Med200397211512212587960

- MiravitllesMde la RozaCMoreraJChronic respiratory symptoms, spirometry and knowledge of COPD among general populationRespir Med2006100111973198016626950

- de MarcoRAccordiniSCerveriIIncidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort of young adults according to the presence of chronic cough and phlegmAm J Respir Crit Care Med20071751323917008642

- HarmsenLThomsenSFIngebrigtsenTChronic mucus hyper-secretion: prevalence and risk factors in younger individualsInt J Tuberc Lung Dis20101481052105820626952

- PelkonenMNotkolaILNissinenATukiainenHKoskelaHThirty-year cumulative incidence of chronic bronchitis and COPD in relation to 30-year pulmonary function and 40-year mortality: a follow-up in middle-aged rural menChest200613041129113717035447

- MartinezCHKimVChenYCOPDGene InvestigatorsThe clinical impact of non-obstructive chronic bronchitis in current and former smokersRespir Med2014108349149924280543