Abstract

Background

Limited information is available regarding medication use in COPD patients from Latin America. This study evaluated the type of medication used and the adherence to different inhaled treatments in stable COPD patients from the Latin American region.

Methods

This was an observational, cross-sectional, multinational, and multicenter study in COPD patients attended by specialist doctors from seven Latin American countries. Adherence to inhaled therapy was assessed using the Test of Adherence to Inhalers (TAI) questionnaire. The type of medication was assessed as: short-acting β-agonist (SABA) or short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA) only, long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), long-acting β-agonist (LABA), LABA/LAMA, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), ICS/LABA, ICS/LAMA/LABA, or other.

Results

In total, 795 patients were included (59.6% male), with a mean age of 69.5±8.7 years and post-bronchodilator FEV1 of 50.0%±18.6%. The ICS/LAMA/LABA (32.9%) and ICS/LABA (27.7%) combinations were the most common medications used, followed by LABA/LAMA (11.3%), SABA or SAMA (7.9%), LABA (6.4%), LAMA (5.8%), and ICS (4.3%). The types of medication most commonly used in each Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2013 category were ICS/LABA (A: 32.7%; B: 19.8%; C: 25.7%; D: 28.2%) and ICS/LAMA/LABA (A: 17.3%; B: 30.2%; C: 33%; D: 41.1%). The use of long-acting bronchodilators showed the highest adherence (good or high adherence >50%) according to the TAI questionnaire.

Conclusion

COPD management in specialist practice in Latin America does not follow the current guideline recommendations and there is an overuse of ICSs in patients with COPD from this region. Treatment regimens including the use of long-acting bronchodilators are associated with the highest adherence.

Introduction

Optimal pharmacological treatment for COPD patients reduces symptoms, reduces the frequency and severity of exacerbations, improves health status, and increases exercise tolerance.Citation1 However, despite the frequent changes in COPD classification systems and the emergence of new inhaled therapies recommended in some new evidence-based guidelines,Citation1–Citation3 poor adherence to treatment and lack of accessibility to these drugs in many countries generate a considerable gap between optimal treatment and real-life prescribing patterns.Citation4–Citation6

In Latin America, the undertreatment and suboptimal treatment of COPD patients occur frequently, with wide variations between countries. The population-based prevalence study of COPD in Latin America (PLATINO)Citation7 showed that only a quarter of COPD patients received any respiratory medication, 75% of patients with a previous medical diagnosis had received respiratory medication in the past year, and over half of treated subjects were on medication without a diagnosis of airway obstruction.Citation8 In primary care settings in Latin America, long-acting bronchodilators (LA-BDs) are frequently underused as regular maintenance therapy for COPD, and the treatment received by patients does not strictly follow the COPD guidelines’ recommendations; short-acting bronchodilators (SA-BDs) were most commonly used as monotherapy in patients with COPD.Citation9 Overtreatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) was also common in patients with a previous diagnosis of COPD.Citation10

No information exists regarding the real-life types and patterns of inhaled medication use in COPD patients attended by specialist doctors in Latin America, nor is there any information on adherence to the different types of medication. Therefore, the aims of this non-interventional study were to describe the types of respiratory medication used in COPD patients attended by specialist doctors overall and according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2013 categories, and to determine the adherence to different inhaled therapies in stable COPD patients from seven Latin American countries.

Methods

The Latin American Study of 24-hour Symptoms in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (LASSYC) was a prospective observational, multicenter, multinational, cross-sectional, non-interventional study in stable COPD patients from seven Latin American countries: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, and Uruguay.Citation11,Citation12 The study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT2789540). Here, we analyzed prescribed medication use and adherence to different inhaled therapies in this patient population.

In total, 795 patients were enrolled and distributed among convenient specialist doctors in the seven selected countries. Each country recruited 100–130 patients and each site around 10–15 patients. The recruitment was competitive in each country after the expected site recruitment time of 1 month, up to a total recruitment period of 3 months. The study team identified suitable ambulatory pulmonology sites (ie, those whose databases had information on diagnostic procedures, etc.) to ensure an adequate sample of both specialist doctors and patients.

The ethics committees for each site approved the study protocol and all patients provided written informed consent (Table S1).

Site staff collected, retrospectively, information from patients’ medical records to determine eligibility, and those patients with stable COPD were screened for inclusion.

The methodology of the study has been described previously. In brief, outpatients ≥40 years of age with a diagnosis of COPD for at least 1 year, at least one spirometry value with a COPD diagnosis using the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.70 criterion in the previous 12 months, current or ex-smokers (≥10 pack-years), and stable disease (without treatment for an exacerbation or changes in current treatment in the previous 2 months) were included in the study.Citation11 Patients with a diagnosis of sleep apnea or any other chronic respiratory disease, or any acute or chronic condition that would limit their ability to participate in the study were excluded.

The following information was collected for each patient: social demographics, health insurance system, lifestyle, smoking history, presence of comorbidities, level of dyspnea, disease severity, prescribed COPD treatments, exacerbation history, and health care resource utilization during the past 12 months.

COPD classification was performed according to the GOLD 2013 criteria for groups A–D based on post-bronchodilator FEV1, exacerbation risk, and level of symptoms.Citation13

The type of medication used was assessed using the following classification: short-acting β-agonist (SABA) or short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA) only, long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), long-acting β-agonist (LABA), LABA/LAMA, ICS, ICS/LABA, ICS/LAMA/LABA, and other (such as methylxanthine, mucolytics, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors).

Assessment of medication adherence

Self-reported adherence to medication was measured using the Test of Adherence to Inhalers (TAI) questionnaire.Citation14

The TAI questionnaire includes 10 items (patient domain), is self-administered, and is scored from 1 to 5 (where 1= worst possible score and 5= best possible score). The total score for the 10-item questionnaire ranges from 10 to 50. Adherence is rated as good (score =50), intermediate (score =46–49), or poor (score ≤45).Citation14

The adherence profiles to inhaled therapies in general and the level of agreement between two patient self-report adherence questionnaires in stable COPD patients from seven Latin American countries have been published elsewhere.Citation11

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included the absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and the mean ± SD for numerical variables. To test for differences in some variables according to the type of medicine taken, a Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables as the medicines are all dichotomous variables. We considered a p-value less than 5% as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13, 2013; StatCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In total, 795 patients were included between May and August 2016 (59.6% male), with a mean age of 69.5±8.7 years and a mean post-bronchodilator FEV1 of 50.0%±18.6% of predicted. The general characteristics of the overall patient population and by country are shown in . Among these patients, 787 (99%) completed the TAI questionnaire. The sample characteristics of the patient population according to the type of medication used are shown in .

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics, overall and by country

Table 2 Clinical profile of patients according to type of medication used

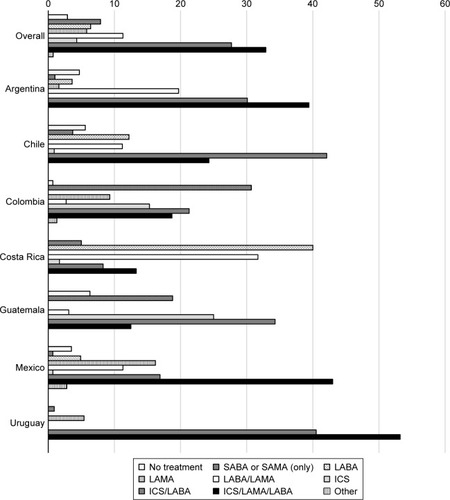

The type and frequency of medication used in patients with COPD, overall and by individual country, are shown in . Approximately 3% of the overall study population were not receiving treatment. The ICS/LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA combinations were the most frequently used treatments in most countries (Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, Mexico, and Uruguay), with more than one-third of patients using an ICS/LAMA/LABA combination. In Colombia, the most common medications used were SABA or SAMA, and in Costa Rica this was LABA monotherapy. A small proportion of patients were using LABA (6.4%) or LAMA (5.8%) monotherapy or dual bronchodilatation (LABA/LAMA [11.3%]) in the overall COPD population (). The pattern of use of respiratory medication, either as-needed or as regular maintenance therapy, is shown in Figure S1. Of the patients who used SA-BD monotherapy (SABA or SAMA), more than 50% used it regularly as a maintenance therapy.

Figure 1 Type and frequency of medication used, overall and by country.

Abbreviations: LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

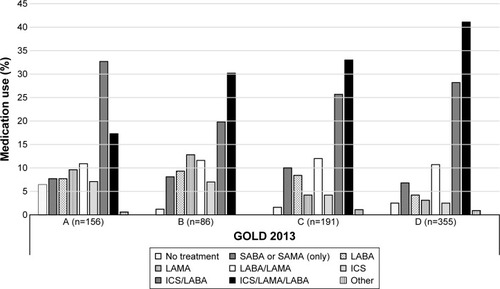

shows the types of medication used according to the GOLD 2013 COPD categories. The medication most frequently used in each category was ICS/LABA (A: 32.7%; B: 19.8%; C: 25.7%; D: 28.2%) and ICS/LAMA/LABA (A: 17.3%; B: 30.2%; C: 33%; D: 41.1%).

Figure 2 Type of medication used according to the GOLD 2013 stage classification in the overall population.

Abbreviations: GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

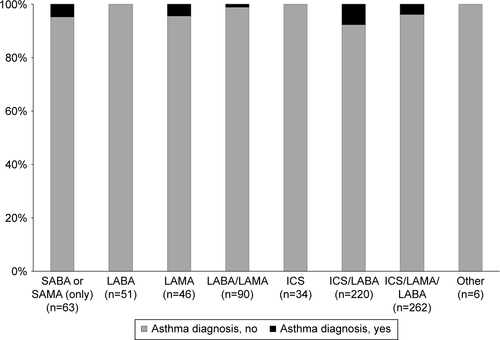

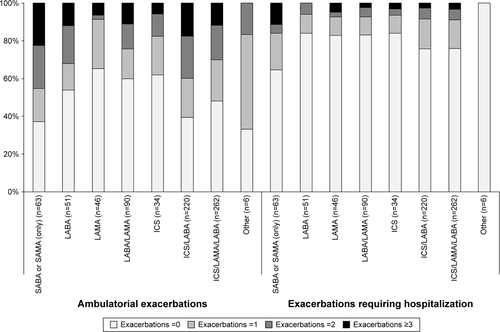

Figures S2 and S3 show the type of medication used according to prior medical diagnosis of asthma and history of exacerbations (ambulatory or requiring hospitalization) in the past year, respectively. The majority of patients (≥90%) using any ICS combination did not have a prior medical diagnosis of asthma (Figure S2). In patients using any ICS combination, more than 35% and 75% of patients did not have an ambulatory exacerbation or an exacerbation requiring hospitalization, respectively.

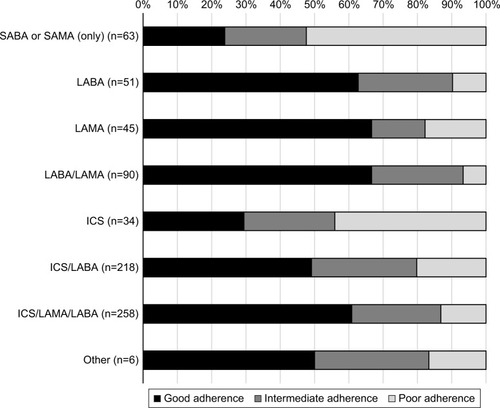

Adherence to treatment in the overall population according to the type of medication used, based on the TAI questionnaire, is shown in . According to the TAI questionnaire, the use of SA-BDs and ICS monotherapy showed the lowest adherence (poor adherence in 52.4% and 44.0% of patients, respectively); treatment with LA-BDs had better adherence (good adherence in >50% of patients) ().

Figure 3 Adherence to treatment (TAI questionnaire) according to the type of medication used in the overall population.

Abbreviations: TAI, Test of Adherence to Inhalers; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Discussion

The main findings of this study on the treatment of stable COPD patients attended by specialist doctors in Latin America were: first, ICS/LAMA/LABA or ICS/LABA combinations were the most frequently used classes of medication in the overall population and also in each of the GOLD 2013 categories; second, a substantial proportion of patients were using an ICS combination without a prior medical diagnosis of asthma or exacerbation history; and third, the use of treatment regimens involving LA-BDs showed the highest adherence (good or high adherence >50%) according to the TAI questionnaire.

Pharmacological overtreatment, in particular the over-prescription of triple therapy in patients with COPD, many of whom have mild disease, has been frequently reported.Citation4,Citation9,Citation10,Citation15–Citation21 In an analysis of a large UK primary care database, Price et al reported that ~50% of COPD patients received an ICS, in combination with either a LABA (26.7%) or a LABA/LAMA (23.2%).Citation4 Similarly, here we found that ICS/LABA and triple therapy were the most frequently used treatments in patients categorized as GOLD A or B and only a small proportion of patients were using LABA or LAMA monotherapy (1.8% and 7.9%, respectively). In another large database study in Spain, up to 45.2% of patients newly diagnosed with COPD were treated with an ICS and up to 12% were receiving triple therapy.Citation6 In a real-life study from France, ICS/LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA combinations were used in 33% and 24% of the total COPD population, respectively.Citation16 In addition, these combinations were commonly used in patients categorized as GOLD A (ICS/LAMA/LABA [20%] and ICS/LABA [16%]) or B (ICS/LAMA/LABA [32%] and ICS/LABA [14%]). A retrospective study from the USA indicates that 25.5% of COPD patients were treated with triple therapy, and the majority of the patients had mild/moderate disease.Citation15

Limited information is available regarding the real-life types and frequencies of medication used in the treatment of COPD patients in Latin America. Data from patients with prior COPD diagnosis in a primary care setting indicate that 64.7% used any bronchodilator, 37.6% used a corticosteroid, and 25.6% used a bronchodilator plus corticosteroid.Citation9,Citation10 LA-BDs appeared to be underused as regular maintenance therapy (<30%), while 79% of patients were using a corticosteroid despite not having airway obstruction or exacerbation.Citation9,Citation10

The results of this study are consistent with those reported in other populations showing the underuse of LA-BD monotherapy (LAMA or LABA) and dual bronchodilatation (LAMA/LABA) as maintenance therapies in COPD patients, as well as the overuse of ICS/LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA combinations in patients in GOLD groups A and B. Regarding the prescribing pattern of ICSs among the countries participating in the study, in six out of seven countries (Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, Mexico, Colombia, and Uruguay) ICSs were used in more than 55% of the patients; only Costa Rica had a low use of ICSs (28%). On the other hand, the countries with the highest use of SA-BDs were Colombia (31%) and Guatemala (19%), and those with the highest use of LA-BDs (without ICS) were Costa Rica (72%) followed by Argentina (25%) and Chile (23%). This suggests that a substantial proportion of patients are not treated with the most appropriate medication according to GOLD recommendations or local guidelines.Citation1,Citation2,Citation22 These findings can be explained by a number of factors, one of which is the low implementation of or low physicians’ adherence to the current COPD guidelines around the world.Citation18–Citation21,Citation23–Citation25 Another factor that may help to explain the differences from the prescribing pattern previously reported in primary care physicians from Latin America,Citation9,Citation10 as well as the high prescription of triple therapy found in the present study, is the sites selected for the study, which were all COPD patients’ centers attended by specialist physicians, who have a greater tendency to prescribe this type of therapy. It is also possible that other factors, not assessed in the present study (such as variations in the characteristics of the local health care systems, medical coverage for respiratory medications, accessibility to medication, and reimbursement or regulatory policies), may contribute to the current COPD treatment practice and explain in part the differences observed among the countries.

The main indication for the use of ICS combination therapy in COPD patients is two or more exacerbations or one hospitalization due to an exacerbation in the past year (GOLD 2013 groups C and D). In addition, the use of ICS has been recommended for patients with the overlap phenotype (asthma plus COPD).Citation26

Analysis from a UK primary care setting showed that 53.7% of the COPD patients without a concomitant diagnosis of asthma were receiving an ICS, as well as 49% and 64% of the patients who had experienced no exacerbations or one exacerbation in the previous year, respectively.Citation4 Similarly, a study involving a primary care population from Latin America reported that 70.4% of patients with a correct prior diagnosis of COPD were receiving a corticosteroid despite not having experienced any exacerbations in the past year.Citation10 In the present study, we also found that more than 90% of the COPD patients using any ICS combination did not have a prior medical diagnosis of asthma, and more than 35% and 75% did not have ambulatory exacerbation or exacerbations requiring hospitalization, respectively. These data allow us to conclude that there is an overuse of ICSs in patients with COPD in the Latin American region. Difficulties in distinguishing between asthma and COPD in adults with airways disease, or in establishing when these two conditions coexist (asthma and COPD overlap), could play an important role in the ICS prescribing pattern.Citation27

Several studies have reported frequent suboptimal adherence to inhaled medication in COPD patients.Citation28–Citation30 Limited information exists regarding adherence according to the different types of medication in these patients. However, a study using pharmacy records found that adherence to medications was poor, with 19.8% of patients adherent to ICS, 30.6% adherent to LABA, and 25.6% adherent to ipratropium.Citation30 A separate study analyzing pharmacy records showed that 54% of patients prescribed a LABA were adherent to therapy while only 40% were adherent to an ICS.Citation28 Data from the Copenhagen General Population Study found that adherence varied from 29% to 56% across COPD GOLD stages 1–4 for ICS/LABA therapy, from 51% to 68% for LAMA monotherapy, and from 25% to 62% for LABA monotherapy.Citation29

A study using a PHARMO database showed that the persistence rates with initial therapy for COPD at 1, 2, and 3 years were 25%, 14%, and 8%, respectively, for LAMA therapy; 21%, 10%, and 6% for LABA therapy; and 27%, 14%, and 8% for ICS/LABA fixed-dose combination therapy.Citation31 Another study reported that ~37% of new users of tiotropium continued treatment for 1 year compared with only 14% for ipratropium, 13% for LABA, and 17% for ICS/LABA.Citation32 In contrast, a large database study from Spain found higher levels of adherence: around 50% of patients newly initiated with LAMA therapy were persisting with their treatment after 9 months.Citation33

To our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated adherence to different inhaled medications using patients’ self-report methods in a selected COPD population. The results of the present study are in line with previous studies showing improved adherence with the use of LA-BDs compared with SA-BD or ICS monotherapy regimens. In addition, improved adherence to LAMA, LABA, or LABA/LAMA treatment regimens compared with ICS/LABA was observed. The well-documented superiority of LA-BDs for improving lung function and quality of life, and reducing exacerbations and hospital admissions compared with SA-BDs, together with the potential advantages of newer, easier-to-use devices, could help to explain the greater adherence to LA-BDs regimens.Citation34,Citation35 That said, the adherence to ICS therapy could be lower than that with LA-BDs because of the lack of a direct symptom-relieving effect of the corticosteroids.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be mentioned. Medication adherence was only assessed using self-reported measurements, and self-reported use frequently leads to an overestimation of medication use. Although the study included a large number of COPD patients from seven countries, it cannot be concluded that the sample is representative of the entire COPD population attended by specialist doctors in Latin America; however, the sample included patients with different degrees of severity and may provide a valid estimation of patients’ characteristics from this region. Finally, since this was a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to analyze prospectively the type of medication used and adherence according to the different types of medication over time.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that the management of COPD patients attended by specialist doctors in Latin America does not usually follow GOLD or local recommendations, particularly regarding the use of LA-BDs, ICS/LABA, and triple therapy in patients with low exacerbation risk or without a prior diagnosis of asthma. Treatment regimens that include LA-BDs are associated with the highest adherence. Further efforts are needed to improve our knowledge on COPD management in specialist practice in the Latin American region and to ensure that COPD patients have access to the most appropriate medication regimens.

Author contributions

For all data, all authors confirm that they have personally reviewed the data, understand the statistical methods employed for the analyses, and have an understanding of these analyses, that the methods are clearly described, and that they are a fair way to report the results. AC, MMO, AM, FCW, MVLV, LM, LR, and MM contributed substantially to the study design, data collection, interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. AM and FCW performed the data analysis while all authors were involved with data interpretation. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to its submission to the International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all members of the LASSYC team of Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay, Chile, Costa Rica, Venezuela, and Spain: Alejandro Casas (Colombia), Maria Montes de Oca (Venezuela), Ana Menezes and Fernando C Wehrmeister (Brazil), Maria Victorina Lopez Varela (Uruguay), Luis Ugalde (Costa Rica), Alejandra Ramirez-Venegas (México), Laura Mendoza (Chile), Ana López (Argentina), Larissa Ramirez (Costa Rica), and Marc Miravitlles (Spain).

This observational study was funded by AstraZeneca Latin America. Editorial support was provided by Dr Ian Wright, Wright Medical Communications Ltd, and funded by AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca had no input into the study design, analysis, or interpretation of the results.

Supplementary materials

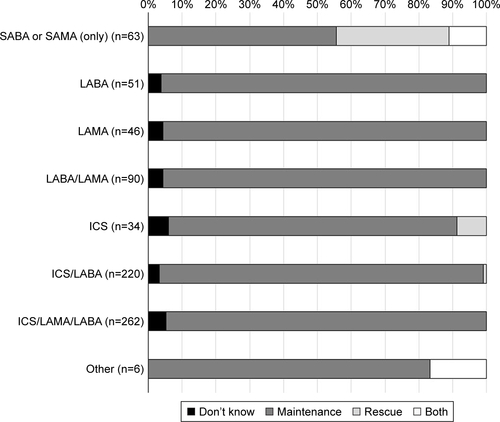

Figure S1 Pattern of use of respiratory medication, either as-needed or as regular maintenance therapy.

Abbreviations: SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

Figure S2 Type of medication used according to prior medical diagnosis of asthma.

Abbreviations: SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

Figure S3 History of exacerbations (ambulatory or requiring hospitalization) in the past year.

Abbreviations: SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

Table S1 Approval committees in the various countries involved in the LASSYC study

Disclosure

AM has been paid for her work as a statistician for the LASSYC study. LR is an employee of AstraZeneca. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VogelmeierCFCrinerGJMartinezFJGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive SummaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195555758228128970

- Montes de OcaMLópez VarelaMVLaucho-ContrerasMEClassification of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to the Latin American Thoracic Association (ALAT) staging systems and the global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (GOLD)Arch Bronconeumol20175339810627956034

- MiravitllesMSoler-CataluñaJJCalleMSpanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC) 2017Pharmacological treatment of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Bronconeumol201753632433528477954

- PriceDWestDBrusselleGManagement of COPD in the UK primary-care setting: an analysis of real-life prescribing patternsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014988990425210450

- MakeBDutroMPPaulose-RamRMartonJPMapelDWUnder-treatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201271922315517

- BarrechegurenMMonteagudoMFerrerJTreatment patterns in COPD patients newly diagnosed in primary care. A population-based studyRespir Med2016111475326758585

- MenezesAMPerez-PadillaRJardimJRChronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence studyLancet200536695001875188116310554

- Lopez VarelaMVMuiñoAPérez PadillaRTreatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 5 Latin American cities: the PLATINO studyArch Bronconeumol2008442586418361870

- Montes de OcaMLopez VarelaMVJardimJStirvulovRSurmontFBronchodilator treatment for COPD in primary care of four Latin America countries: the multinational, cross-sectional, non-interventional PUMA studyPulmon Pharmacol Ther2016381016

- JardimJRStirbulovRMorenoDZabertGLopez-VarelaMVMontes de OcaMRespiratory medication use in primary care among COPD subjects in four Latin American countriesInt J Tuberc Lung Dis201721445846528284262

- Montes de OcaMMenezesAWehrmeisterFCAdherence to inhaled therapies of COPD patients from seven Latin American countries: the LASSYC studyPLoS One201712e018677729140978

- MiravitllesMMenezesALópez VarelaMVPrevalence and impact of respiratory symptoms in a population of patients with COPD in Latin America: the LASSYC observational studyRespir Med20181341626929413510

- VestboJHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- PlazaVFernandez-RodriguezCMeleroCValidation of the “Test of the Adherence to Inhalers” (TAI) for asthma and COPD patientsJ Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv201629214215226230150

- SimeoneJCLuthraRKailaSInitiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the USInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201612738328053518

- BurgelPRDesléeGJebrakGReal-life use of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD patients versus the GOLD proposals: a paradigm shift in GOLD 2011?Eur Respir J20144341201120324176996

- BrusselleGPriceDGruffydd-JonesKThe inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UKInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102207221726527869

- WhitePThorntonHPinnockHGeorgopoulouSBoothHPOvertreatment of COPD with inhaled corticosteroids – implications for safety and costs: cross-sectional observational studyPLoS One2013810e7522124194824

- FranssenFMSpruitMAWoutersEFDeterminants of polypharmacy and compliance with GOLD guidelines in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011649350122069360

- SenEGucluSZKibarIAdherence to GOLD guideline treatment recommendations among pulmonologists in TurkeyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102657266326715844

- TuranOEmreJCDenizSBaysakATuranPAMiriciAAdherence to current COPD guidelines in TurkeyExpert Opin Pharmacother201617215315826629809

- Montes de OcaMLópez VarelaMVAcuñaAALAT-2014 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Clinical Practice Guidelines: questions and answersArch Bronconeumol201551840341625596991

- AscheCVLeaderSPlauschinatCAdherence to current guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among patients treated with combination of long-acting bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroidsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012720120922500120

- BourbeauJSebaldtRJDayAPractice patterns in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary practice: the CAGE studyCan Respir J2008151131918292848

- CorradoARossiAHow far is real life from COPD therapy guidelines? An Italian observational studyRespir Med2012106798999722483189

- SinDDMiravitllesMManninoDMWhat is asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS)? Towards a consensus definition from a roundtable discussionEur Respir J201648366467327338195

- PlazaVÁlvarezFCalleMConsensus on the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) Between the Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC) and the Spanish Guidelines on the Management of Asthma (GEMA)Arch Bronconeumol201753844344928495077

- CecereLMSlatoreCGUmanJEAdherence to long-acting inhaled therapies among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)COPD20129325125822497533

- IngebrigtsenTSMarottJLNordestgaardBGLow use and adherence to maintenance medication in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the general populationJ Gen Intern Med2015301515925245885

- HuetschJCUmanJEUdrisEMAuDHPredictors of adherence to inhaled medications among veterans with COPDJ Gen Intern Med201227111506151222782274

- Penning-van BeestFvan Herk-SukelMGaleRLammersJWHeringsRThree-year dispensing patterns with long-acting inhaled drugs in COPD: a database analysisRespir Med2011105225926520705441

- Breekveldt-PostmaNSKoerselmanJErkensJALammersJWHeringsRMEnhanced persistence with tiotropium compared with other respiratory drugs in COPDRespir Med200710171398140517368011

- MonteagudoMRosetMRodriguez-BlancoTMuñozLMiravitllesMCharacteristics of COPD patients initiating treatment with aclidinium or tiotropium in primary care in Catalonia: a population-based studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017121145115228442901

- CheyneLIrvin-SellersMJWhiteJTiotropium versus ipratropium bromide for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20159CD009552

- AppletonSPoolePSmithBVealeALassersonTJChanMMLong-acting beta2-agonists for poorly reversible chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20063CD001104