Abstract

Purpose

Chronic bronchitis is thought to occur in elderly patients, and smoking seems to be an important risk factor. The outcomes related to the age of onset in patients with chronic bronchitis are still unclear.

Patients and methods

A retrospective study was conducted on deceased patients whose diagnosis included bronchitis from 2010 to 2016. Patients were separated into two groups according to the age of onset (Group I, age ≤50 years old; Group II, age >50 years old). Information regarding disease course, smoking history, death age, number of admissions per year, Hugh Jones Index, and self-reported comorbidities of the patients was recorded.

Results

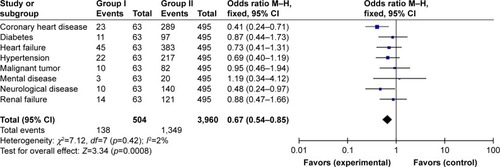

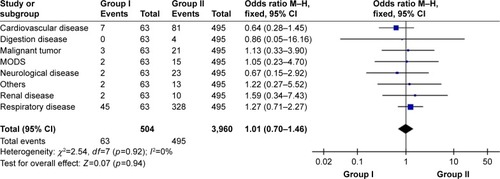

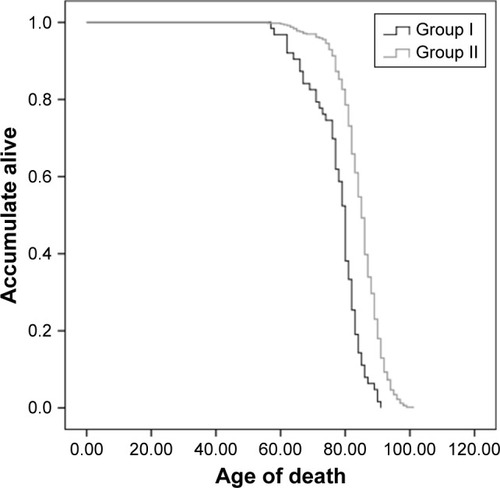

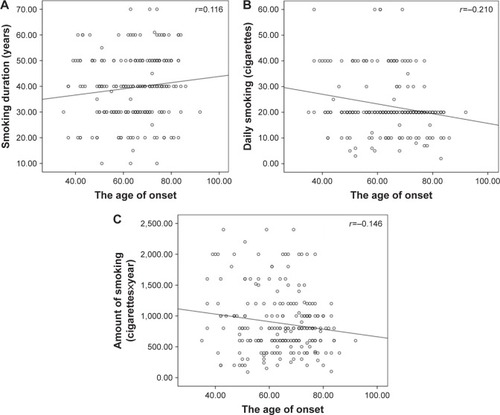

The courses of chronic cough and sputum were 33.38±7.73 years and 14.44±8.60 years in Group I and Group II, respectively (p<0.05). The death ages of Group I and Group II were 77.65±7.87 years and 84.69±6.67 years, respectively (p<0.05). There was a significant negative correlation between the number of hospital admissions per year and the age of onset. The age of onset was negatively associated with daily smoking count (r=−0.210) and total smoking count (r=−0.146). In Group I, there were fewer cases of coronary heart disease (OR =0.41 [0.24–0.71]), neurological diseases (OR =0.48 [0.24–0.97]), and total comorbidities (OR =0.67 [0.54–0.85]) than in Group II.

Conclusion

Patients with early onset chronic bronchitis had a longer history, younger death age, poorer health status, and lower incidence of comorbidities.

Introduction

Chronic bronchitis is often thought to be an age-related disease that occurs after years of cigarette smoking. It is characterized by chronic coughing, chest tightness, and dyspnea. Chronic bronchitis occurs not only in older individuals but also in younger people. The age of onset is determined by the interaction of gene polymorphisms and environmental factors. Smoking status,Citation1 location, occupational dust exposure, type of house,Citation2 radiation,Citation3 allergic history, childhood asthma, parental bronchitis symptoms,Citation4 and biomass fuelsCitation5 are all related to the incidence of chronic bronchitis. Chronic bronchitis also shows a moderate familial aggregation, particularly in women.Citation6 The T5-TG12 haplotype of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor (CFTR) gene,Citation7 CFTR dysfunction due to smoking,Citation8 and aberrant expression of epigenetic markers may cause a higher incidence of chronic bronchitis.Citation9 Although chronic bronchitis is associated with impaired quality of life, hospital admissions, and increased mortality,Citation10 it has not garnered much attention since the introduction of the term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Previous studies have shown that chronic bronchitis notably increases the risk of continuous airflow limitation and all-cause mortality in subjects <50 years old, but not among subjects ≥50 years old.Citation11 Few studies have focused on the clinical features, related factors, and outcomes according to the age of onset in chronic bronchitis. Our study aims to determine the relationship between the age of onset and severity of chronic bronchitis, the influencing factors of the age of onset on comorbidities, and the cause of death in patients with chronic bronchitis.

Patients and methods

Participants

We conducted a retrospective study by reviewing the medical records of deceased patients admitted to the Shanghai Putuo District Central Hospital and whose diagnosis included chronic bronchitis (ICD-10: J42) from 2010 to 2016. Data were acquired from the hospital database. This study enrolled 558 patients whose baseline characteristics, disease history, and self-reported comorbidities were recorded.

Patients with chronic bronchitis were defined as having a sputum-producing cough daily for at least 3 months per year for two consecutive years. Smoking patients are defined as having a smoking history, including current and former smokers. Smoking history included smoking duration, daily smoking count, and total smoking count. The number of hospital admissions per year was considered to be an average admission of the past year.

The age of onset was defined as the first occurrence of recurrent cough and sputum, which was reported by the patients in their medical records as a retrospective indicator. Patients were separated into two groups according to the age of onset. The age of Group I was ≤50 years, while the participants in Group II were >50 years old. The course of disease was detailed through retrospective data and defined as the occurrence of this disease until the patients’ death. The clinical dyspnea index was evaluated using the Hugh Jones Index. The self-reported comorbidities included coronary heart disease (ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and coronary artery disease), diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, malignant tumor, mental disease (depression, mania, dementia), neurological disease, and renal failure (renal function lower than chronic kidney disease [CKD] stage III), all of which were referred from the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous data were compared using the Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon’s test, while categorical data were compared using the chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests. Spearman’s rank correlation techniques were used to analyze the relationships between several continuous variables. The survival analysis used the Cox proportional hazard model. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for single comparisons. All the reported p-values were two sided. Data were analyzed using the SPSS 22.00 software package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Putuo Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The patients’ approval or informed consent was not required for a retrospective review of their records. The patient data used in our study did not include any identifying information.

Results

Five hundred fifty-eight deceased patients who met all of the criteria were included in this study. There were 405 males (72.6%) and 153 females (27.4%). Patients were divided into two groups according to the age of onset. Group I (the age of onset was ≤50 years) included 63 patients, whereas Group II (the age of onset was >50 years) included 495 patients.

Longer course of disease, earlier age of death, and poorer dyspnea status in early onset chronic bronchitis patients

The average course of chronic cough and sputum was 16.71±10.66 years. The age of onset was 67.32±12.35 years, and the age of death was 83.89 years. The course of chronic cough and sputum was notably longer in Group I than in Group II. The Hugh Jones Index showed significant differences between these two groups. The age of onset was significantly negatively correlated with the number of hospital admissions per year ().

Table 1 The relationship between patient history and the age of onset

The correlation between smoking history and the age of onset

There were 233 patients with a history of smoking, of which only 35 patients had not quit smoking. There were more patients with a smoking history in Group I than in Group II (). There were no differences between Group I and Group II in terms of daily smoking counts, smoking duration, and total smoking counts. Furthermore, the age of onset was negatively associated with daily smoking counts (r=−0.210, p=0.001) and total smoking counts (r=−0.146, p=0.027), but there was no correlation between the duration of smoking and the age of onset (r=−0.116, p=0.078, ).

Table 2 Smoking history according to the age of onset

Figure 1 The correlation between smoking history and the age of onset.

The incidence of self-reported comorbidities according to the age of onset in patients with chronic bronchitis

There were eight comorbidities considered, including coronary heart disease (ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and coronary artery disease), diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, malignant tumor, mental disease (depression, mania, dementia), neurological disease, and renal failure (renal function lower than CKD stage III). In Group I (early onset chronic bronchitis patients), there were fewer cases of coronary heart diseases (OR =0.41 [0.24–0.71]), neurological diseases (OR =0.48 [0.24–0.97]), and total complications (OR =0.67 [0.54–0.85]) than in Group II (late-onset chronic bronchitis patients). However, the incidences of diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, malignant tumor, mental disease (including depression, mania, and dementia), and renal failure (renal function lower than CKD stage III) were similar in the two groups ().

The relationship between cause of death and the age of onset

There was no difference in the cause of death in the two groups. Most patients died from chronic respiratory disease (37.6%) and cardiovascular disease (28.9%). Other cause of death included neurological disease, digestion disease, malignant tumor, and so on ().

Discussion

Chronic bronchitis often occurs in elderly individuals. An investigation of community-dwelling individuals aged 40–80 years found that the incidence of chronic bronchitis was 12.7%,Citation12 and other studies observed similar results.Citation13,Citation14 Though smoking is the most important risk factor, low socioeconomic class and urban living,Citation10,Citation15 gender, asthma history,Citation16 changes in living habits,Citation14 odor or the musty smell of mildew/mold in the house, exposure to 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl)ethane (DDT),Citation49 body mass index,Citation17 and air pollutionCitation18 play roles in the development of chronic bronchitis. Studies have demonstrated that aging (especially >50 years old) is also a high risk factor for chronic bronchitis.Citation14,Citation19 As a result of persistent mucus hypersecretion, longer courses of productive cough are related to quicker reductions in the lung function.Citation20 Early onset chronic bronchitis has a higher risk to develop into irreversible airflow limitation and all-cause mortality.Citation11

Though chronic bronchitis is related to aging, our study found that the early onset patients had longer productive cough courses, in which the age of death was much lower than the other patients. Lindberg et al showed that productive cough has a significantly higher risk for death even after adjustment for common risk factors.Citation21 With the progress of disease, chronic bronchitis has an increased risk for frequent exacerbation.Citation22,Citation23 Not only did patients with chronic bronchitis have a higher frequency of exacerbation, but also had longer stays in the hospital.Citation23 We found that the age of onset is negatively correlated with the number of hospital admissions, which was similar to these results. The earlier the onset, the more frequently these patients presented with exacerbation.

In the early onset group, patients showed higher Hugh Jones Index values indicating a poorer health status in our study. Respiratory symptoms are common in chronic bronchitis or COPD. Previous studies have shown that cough is associated with the health-related quality of life,Citation24 that is, poor quality of life, and breathing problems of chronic bronchitis that limit daily activities.Citation25 Patients with chronic bronchitis had a greater incidence of chronic dyspnea and activity restriction,Citation26 and chronic bronchitis significantly lowered exercise capacity in COPD patients.Citation27 There may be a reasonable explanation for the occurrence of early onset chronic bronchitis with longer courses of disease and higher activity restrictions. On the other hand, Riesco et al discovered that active smoking was significantly associated with higher grades of dyspnea.Citation28 Long-term smoking negatively affects the health of patients.Citation29 The early onset subjects showed higher rates of smoking, which may lead to increase levels of dyspnea shown as higher Hugh Jones Index scores.

Smoking has been proven to be a definitive risk factor for the incidence of chronic bronchitis. Liu et al conducted a prospective study to assess the duration of smoking and airway symptoms. They found that smoking duration showed a linear relationship with symptoms including frequent productive cough, frequent shortness of breath, and shortness of breath affecting physical activity.Citation29 In our study, though duration of smoking was not related to the age of onset, daily smoking count and total smoking count are negatively associated with the age of onset. Using the time to first cigarette (TTFC) after waking parameter as an indicator of nicotine dependence, current smokers who were found to have shorter TTFC times had an increased risk of chronic bronchitis.Citation30 While quitting or reducing smoking might lead to fewer chronic productive cough symptoms,Citation31 other studies have shown that the smokers who quit because of illness had a significantly higher prevalence of chronic respiratory disease.Citation32 Smoking-related chronic mucus hypersecretion usually resolves following smoking cessation, but the duration of smoking correlated with poorer airway disease activity that reflected the underlying course.Citation20 There were strong associations between smoking history (including current smokers and ex-smokers) and high incidence of chronic respiratory diseases.Citation32 In our study, the daily smoking count and total smoking count were greater with earlier onset, which could perhaps explain why these subjects had a younger age of onset. We found that early onset patients had more active smoking histories and a higher smoking rate than the other group. Not only did smoking history has an impact on the incidence of chronic bronchitis, but also the amount of cigarettes smoked contributed to this disease.

Subjects with physician-diagnosed COPD were more likely have coexisting arthritis, depression, osteoporosis, cancer, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, and stroke.Citation33 Our study found that heart failure, coronary heart disease, and hypertension are the most common complications. Furthermore, in the early onset group, the incidences of coronary heart disease and neurological disease were lower than in the other group. We speculate that as patients grow older, these age-related diseases become more common.

Renal failure is an often neglected problem with regard to chronic bronchitis. A previously conducted meta-analysis demonstrated that COPD was found to be associated with a significantly increased prevalence of CKD (OR =2.20).Citation34 We found that the incidence of chronic renal failure was similar in both groups, so this disease may not be associated with the age of onset.

Chronic bronchitis increased the risk of ischemic events in all age groups. This observation reached significance for patients >60 years of age, especially over the previous 2 months.Citation35 The early onset age group presented with a lower incidence of neurological disease likely because these diseases are associated with aging.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is becoming more common. Previous research has shown that the incidence of diabetes is associated with accumulated smoking exposure, impaired spirometry pattern pulmonary function, reduced 6-minute walking distance without the influence of body mass index, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.Citation36 Patients with chronic bronchitis have an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, which is independent of smoking. In addition, chronic bronchitis has a genetic correlation to diabetes.Citation37 However, there is a decreased incidence of inflammatory diseases such as chronic bronchitis in diabetic patients; thus, type 2 diabetes might reduce the risk of these diseases.Citation38 We found that there is no difference between the two groups in terms of the incidence of diabetes. Both aging and chronic inflammation might interact in diabetes as a comorbidity of chronic bronchitis. Although DM was not associated with reduced quality of life and poorer pulmonary function, untreated DM was related to reduced quality of life and worse pulmonary function.Citation39

Lung cancers are more common in chronic bronchitis. Several studies have found that COPD increases the risk of lung cancer,Citation40 and that these lung cancers might be more aggressive.Citation41 Other malignant tumors were found in our study, including colorectal cancer or leukemia. Some are associated with a history of smoking,Citation42 while some are not well known.

In our study, there were no differences in the incidence of mental illness between the two groups, but it is worth noting that both groups of chronic bronchitis patients presented with mental illness. Mental illnesses, especially depression, gradually increaseCitation43 and become a threat to health in elderly individuals. Both depression and chronic respiratory disease lead to cognitive impairments at the early stages of chronic airway damage and progress with worsening conditions.Citation44 Individuals with mental illness have a significantly increased incidence of chronic physical health disorders compared with people without mental illness.Citation45 Patients with chronic bronchitis presented with worse mental well-being than those without chronic bronchitis.Citation46 Therefore, clinicians and researchers should pay more attention to the mental state of patients with chronic bronchitis.

We found that most patients died from chronic respiratory diseases, which was similar to other studies.Citation47 There was no difference between the two groups and no differences in all-cause of death in the patients. Instant airway inflammation and longer durations of smoking may account for the earlier death of patients. Mekov et al discovered that the risk factors for increased mortality were age, FEV1 values, severe exacerbation in the previous year, and reduced quality of life.Citation48 Chronic bronchitis increased all-cause mortality and mortality from respiratory causes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer.Citation23 In our study, early onset patients had more frequent exacerbation and poorer health status, which could cause death at younger ages.

Our retrospective study on chronic bronchitis focused on the case histories of deceased patients. Many of these subjects were in critical condition with a long course of disease, which may have introduced some bias into the dataset. Until now, little research focusing on the patient’s history prior to death has been conducted, and as a result, this study could lay the foundation for future investigations that center on early onset patients.

Conclusion

We found that patients with early onset chronic bronchitis had a longer history, younger death age, more smokers, poorer health status, and lower incidence of comorbidities. Further, we need a large, prospective cohort study focusing on the age of onset in chronic bronchitis.

Acknowledgments

LZ has received grants for scientific work from the Foundation of the budget project of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China. XW has received grants for scientific work from the Foundation of the Putuo key clinical specialist construction Programs in China and the Foundation of Department of Respiratory Medicine Development Fund of Putuo District in China.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PärnaKPõldMRingmetsIPhysicians’ views on the role of smoking in smoking-related diseases: findings from cross-sectional studies from 1982–2014 in EstoniaTobInduc Dis20171531

- MaheshPAJayarajBSChayaSKVariation in the prevalence of chronic bronchitis among smokers: a cross-sectional studyInt J Tuberc Lung Dis201418786286924902567

- AzizovaTVZhuntovaGVHaylockRChronic bronchitis incidence in the extended cohort of Mayak workers first employed during 1948–1982Occup Environ Med201774210511327647620

- DharmageSCPerretJLBurgessJACurrent asthma contributes as much as smoking to chronic bronchitis in middle age: a prospective population-based studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016111911192027574415

- SehgalMRizwanSAKrishnanADisease burden due to biomass cooking-fuel-related household air pollution among women in IndiaGlob Health Action2014712532625373414

- MeteranHBackerVKyvikKOSkyttheAThomsenSFHeredity of chronic bronchitis: a registry-based twin studyRespir Med201410891321132625049143

- WangPNaruseSYinHThe susceptibility of T5-TG12 of the CFTR gene in chronic bronchitis occurrence in a Chinese population in Jiangsu province, ChinaJ Biomed Res201226641041723554779

- WuDDSongJBartelSKrauss-EtschmannSRotsMGHylkemaMNThe potential for targeted rewriting of epigenetic marks in COPD as a new therapeutic approachPharmacol Ther Epub2017819

- RajuSVTateJHPeacockSKImpact of heterozygote CFTR mutations in COPD patients with chronic bronchitisRespir Res2014151824517344

- AxelssonMEkerljungLErikssonJChronic bronchitis in West Sweden – a matter of smoking and social classEur Clin Respir J201633031927421832

- GuerraSSherrillDLVenkerCCeccatoCMHalonenMMartinezFDChronic bronchitis before age 50 years predicts incident airflow limitation and mortality riskThorax2009641089490019581277

- MarcusBSMcAvayGGillTMVazFCARespiratory symptoms, spirometric respiratory impairment, and respiratory disease in middle-aged and older personsJ Am Geriatr Soc201563225125725643966

- MwangiJKulaneAVan HoiLChronic diseases among the elderly in a rural Vietnam: prevalence, associated socio-demographic factors and healthcare expendituresInt J Equity Health20151413426578189

- LandisSHMuellerovaHManninoDMContinuing to Confront COPD International Patient Survey: methods, COPD prevalence, and disease burden in 2012–2013Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014959761124944511

- MieleCHJaganathDMirandaJJUrbanization and daily exposure to biomass fuel smoke both contribute to chronic bronchitis risk in a population with low prevalence of daily tobacco smokingCOPD201613218619526552585

- HolmMTorénKAnderssonEIncidence of chronic bronchitis: a prospective study in a large general populationInt J Tuberc Lung Dis201418787087524902568

- PahwaPKarunanayakeCPRennieDCPrevalence and associated risk factors of chronic bronchitis in First Nations peopleBMC Pulm Med20171719528662706

- MajiKJAroraMDikshitAKBurden of disease attributed to ambient PM2.5 and PM10 exposure in 190 cities in ChinaEnviron Sci Pollut Res Int20172412115591157228321701

- TutarNYeşilkayaSMemetoğluMEÖzelDBoşnakEThe prevalence of chronic bronchitis in adults living in the center of GumushaneTuberkToraks2013613209215

- AllinsonJPHardyRDonaldsonGCShaheenSOKuhDWedzichaJAThe presence of chronic mucus hypersecretion across adult life in relation to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease developmentAm J Respir Crit Care Med2016193666267226695373

- LindbergASawalhaSHedmanLLarssonLGLundbäckBRönmarkESubjects with COPD and productive cough have an increased risk for exacerbations and deathRespir Med20151091889525528948

- LahousseLLJMSJoosGFFrancoOHStrickerBHBrusselleGGEpidemiology and impact of chronic bronchitis in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J2017502160247028798087

- PelkonenMKNotkolaIKLaatikainenTKJousilahtiPChronic bronchitis in relation to hospitalization and mortality over three decadesRespir Med2017123879328137502

- DesleeGBurgelPREscamillaRImpact of current cough on health-related quality of life in patients with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016112091209727695305

- AccordiniSCorsicoAGCalcianoLThe impact of asthma, chronic bronchitis and allergic rhinitis on all-cause hospitalizations and limitations in daily activities: a population-based observational studyBMC Pulm Med2015151025880039

- ElbehairyAFRaghavanNChengSPhysiologic characterization of the chronic bronchitis phenotype in GOLD grade IB COPDChest201514751235124525393126

- ZhangWLuHPengLChronic bronchitis leads to accelerated hyperinflation in COPD patients during exerciseRespirology201520461862525799924

- RiescoJAAlcázarBTriguerosJACampuzanoAPérezJLorenzoJLActive smoking and COPD phenotype: distribution and impact on prognostic factorsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017121989199928740378

- LiuYPleasantsRACroftJBSmoking duration, respiratory symptoms, and COPD in adults aged ≥45 years with a smoking historyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101409141626229460

- GuertinKAGuFWacholderSTime to first morning cigarette and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: smokers in the PLCO cancer screening trialPLoS One2015105e012597325985429

- KainuAPallasahoPPietinalhoANo change in prevalence of symptoms of COPD between 1996 and 2006 in Finnish adults – a report from the FinEsS Helsinki StudyEur Clin Respir J201633178027534614

- KurmiOPLiLWangJCOPD and its association with smoking in the Mainland China: a cross-sectional analysis of 0.5 million men and women from ten diverse areasInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20151065566525848242

- SchnellKWeissCOLeeTThe prevalence of clinically-relevant comorbid conditions in patients with physician-diagnosed COPD: a cross-sectional study using data from NHANES 1999–2008BMC Pulm Med2012122622695054

- GaddamSGunukulaSKLohrJWAroraPPrevalence of chronic kidney disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisBMC Pulm Med201616115827881110

- Piñol-RipollGde la PuertaISantosSPurroyFMostaceroEChronic bronchitis and acute infections as new risk factors for ischemic stroke and the lack of protection offered by the influenza vaccinationCerebrovasc Dis200826433934718728360

- KinneyGLBakerEHKleinOLPulmonary predictors of incident diabetes in smokersChronic Obstr Pulm Dis20163473974727795984

- MeteranHBackerVKyvikKOSkyttheAThomsenSFComorbidity between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and type 2 diabetes: a nation-wide cohort twin studyRespir Med201510981026103026044811

- ZhengYZhangGChenZZengQRelationship between type 2 diabetes and inflammation diseases: cohort study in Chinese AdultsIran J Public Health20154481045105226587468

- MekovEVSlavovaYGGenovaMPDiabetes mellitus type 2 in hospitalized COPD patients: impact on quality of life and lung functionFolia Med (Plovdiv)2016581364127383876

- GonzalezJMarínMSánchez-SalcedoPZuluetaJJLung cancer screening in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Transl Med20164816027195278

- Sanchez-SalcedoPZuluetaJJLung cancer in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, it is not just the cigarette smokeCurr Opin Pulm Med201622434434927077725

- BailieLLoughreyMBColemanHGLifestyle risk factors for serrated colorectal polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysisGastroenterology201715219210427639804

- KimMTKimKBHanHRHuhBNguyenTLeeHBPrevalence and predictors of depression in Korean American elderly: findings from the memory and aging study of Koreans (MASK)Am J Geriatr Psychiatry201523767168325554484

- Dal NegroRWBonadimanLTognellaSBricoloFPTurcoPExtent and prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic non-obstructive bronchitis, and in asymptomatic smokers, compared to normal reference valuesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014967568325061286

- ScottDBurkeKWilliamsSHappellBCanoyDRonanKIncreased prevalence of chronic physical health disorders in Australians with diagnosed mental illnessAust N Z J Public Health201236548348623025372

- MeekPMPetersenHWashkoGRChronic bronchitis is associated with worse symptoms and quality of life than chronic airflow obstructionChest2015148240841625741880

- PesceGMortality rates for chronic lower respiratory diseases in Italy from 1979 to 2010: an age-period-cohort analysisERJ Open Res201621000932015

- MekovESlavovaYTsakovaAOne-year mortality after severe COPD exacerbation in BulgariaPeer J20164e278827994981

- YeMBeachJMartinJWSenthilselvanAAssociation between lung function in adults and plasma DDT and DDE levels: results from the Canadian Health Measures SurveyEnviron Health Perspect2015123542242725536373