Abstract

The objective of this review was to examine the prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) in individuals with COPD. A computer-based literature search of CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO and Embase databases was performed. Studies reporting the prevalence of OA among a cohort of individuals with COPD were included. The sample size varied across the studies from 27 to 52,643 with a total number of 101,399 individuals with COPD recruited from different countries. The mean age ranged from 59 to 76 years. The prevalence rates of OA among individuals with COPD were calculated as weighted means. A total of 14 studies met the inclusion criteria with a prevalence ranging from 12% to 74% and an overall weighted mean of 35.5%. Our findings suggest that the prevalence of OA is high among individuals with COPD and should be considered when developing and applying interventions in this population.

Introduction

COPD is characterized by symptoms of dyspnea and reduced exercise tolerance.Citation1 It is widespread globally and destined to become the third most common cause of mortality within the next few years.Citation2,Citation3 COPD is a leading cause of disability.Citation4,Citation5 Although the primary pathophysiology is respiratory in COPD, several secondary impairments and co-occurring cardiovascular, metabolic and musculoskeletal conditions have been noted.Citation6–Citation14 Inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, prescribed corticosteroids, hypoxemia and hypercapnia all contribute to the extra-pulmonary manifestations such as cardiovascular compromise, osteoporosis and muscle dysfunction.Citation15,Citation16

An important co-occurring condition is osteoarthritis (OA), a degenerative joint disease characterized by damaged articular cartilage, bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, muscle weakness and ligamentous damage.Citation17,Citation18 OA is also a widely prevalent cause of disability, which is responsible for chronic pain and diminished exercise tolerance.Citation19–Citation21 Many risk factors for OA include age, weight, being female, ethnicity, previous joint injury or repetitive use, muscle weakness and joint laxity.Citation22

As both COPD and OA diminish physical activity and increase the time spent in sedentary behavior,Citation1,Citation23 the co-occurrence of these two conditions is important as both promote decreased participation and a diminution in health-related quality of life.Citation24–Citation26 Notwithstanding the abovementioned information, there is very limited information regarding the prevalence of OA among those with COPD. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review to estimate the mean prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD.

Methods

The review protocol followed PRISMA guidelinesCitation27 and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017055795).

Search strategy and study selection

A systematic computerized literature search of Medline, CINAHL, Embase and PsycINFO databases was carried out with the timescale starting from their inception up to April 2017. The keywords used to carry out the search were as follows: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (MeSH), osteoarthritis (MeSH) and prevalence (MeSH). The detailed search strategy for each database is provided in the Supplementary materials.

We included studies reporting the prevalence of OA in a cohort of individuals with COPD. Articles where individuals with COPD could not be isolated from the overall sample or where OA could not be distinguished from other comorbidities (such as rheumatoid arthritis) were excluded. Articles that reported the co-occurrence of COPD and OA without referring to the main diagnosis and comorbidity were also excluded.

Case–control, cohort, cross-sectional and interventional studies that reported the prevalence of OA as a comorbidity in a sample of individuals with COPD were included, while conference articles, editorials and non-English articles were excluded. Reviews were excluded, although their reference lists were searched manually for potentially relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers (AW, DB). The data extracted were the following: full citation, type of study, country of origin of the study, sample size (of individuals with COPD), mean and SD of the age of the sample, percentage of females included, the races/ethnicities of the population examined, percentage of overweight and/or obese individuals, smoking status and percentage of OA among the sample. The three factors, age, sex and obesity, are common to both diseases. Prevalence rates of OA in individuals with COPD were calculated as weighted means, whereby the sample size of each study was multiplied by the corresponding prevalence rate and divided by the total sample size of all the studies. The overall mean prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD was the sum of the weighted means. A similar methodology was performed previously elsewhere.Citation28

During the screening process, it was evident that some studies examined patients from the same database. To avoid the bias that might be caused by the inclusion of multiple studies of the same cohort on the calculated prevalence mean, only the larger sample size study was included.

Assessment of study quality

Quality assessment of the included studies was undertaken according to the “checklist for prevalence studies” as suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute.Citation29 This tool consists of nine questions aimed at addressing the possibility of bias in the design, methods and analysis for studies that include prevalence data. The questions are self-explanatory and answers are as follows: yes, no, unclear or not applicable. Question 6 on methods was answered with “yes” if the diagnoses of both COPD and OA were based on diagnostic criteria. If the conditions (or one of them) were assessed using observer reported, or self-reported scales, then the question was answered by “no.” Question 7 on reliability of identifying the conditions was answered with “yes” only if both conditions were measured in the same way for all participants.Citation29

Two researchers (DB, AW) conducted the quality assessment separately with any contestations being solved by discussion. The assessment of study quality had no impact on the inclusion or exclusion of the study.

Results

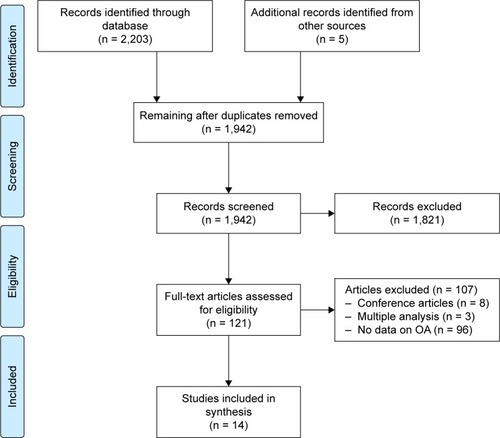

The search resulted in 2,203 articles being identified, of which 266 were duplicates. A total of 1,821 abstracts were excluded based on being unrelated to the topic.

Another 107 articles were excluded for various reasons, including the following: conference articles (eight articles); not including data on OA (92 articles); multiple analysis of the same patients (three articles). The manual search resulted in identifying five additional articles. The PRISMA flowchart from articles identified to those included is shown in .

The articles included in the review and their characteristics are summarized in . Six studiesCitation30,Citation33,Citation35,Citation38–Citation40 were conducted on populations in the USA, and one studyCitation34 examined patients from nine countries. The remainder (published in English) were from the following: the Netherlands,Citation31,Citation41 UK,Citation32,Citation42 Korea,Citation37 South AfricaCitation36 and Germany.Citation43 Seven studiesCitation31,Citation33,Citation37–Citation39,Citation42,Citation43 (50%) followed the observational cohort design; sixCitation30,Citation32,Citation34–Citation36,Citation41 were cross-sectional (43%) and only oneCitation40 (7%) was a case–control study. Studies varied in sample sizeCitation39,Citation42 (27–52,643) as well as ageCitation33,Citation42 (59.3–76 years). In six studies,Citation32–Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation40 data on age and/or sex could not be extracted, and in five,Citation33,Citation36,Citation40–Citation42 data on obesity was unavailable. Seven studiesCitation31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42 out of 14 reported data on smoking status among their sample.

Table 1 Characteristics of the included studies with the timescale starting from the inception of the databases up to April 2017

The prevalence of OA varied across the studies from 11.9%Citation37 to 74%,Citation42 and the weighted mean of the prevalence of OA varied from 0.02%Citation36,Citation42 to 22.7%.Citation39 The overall weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD for the 14 identified studies was 35.5%.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The quality assessment results are illustrated in . A total of 10 articles (71%) used self-reported diagnosis to diagnose COPD and OA. In 11 studies (79%), the question regarding the adequacy of response rate was marked as not applicable as the studies were observational with information extracted from databases ().

Table 2 The quality assessment results for the included articles starting from the inception of the databases to April 2017

We calculated the weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD in 10 articles in which COPD and/or OA were self-reported and in the four studies in which COPD and/or OA were measured objectively, and noted prevalence rates of 30.7% and 37.6%, respectively.

Discussion

This is the first article that systematically examined the prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD. In a sample of more than 100,000 individuals with COPD, we noted prevalence rates ranging from 12% to 74% across the studies with a weighted average of 35.5%. The wide ranges of the prevalence rates might well be explained by the heterogeneity of the study designs, cohort characteristics, sample size and method of sampling. In some studies, COPD was diagnosed without spirometric confirmation, and in others, OA was not confirmed radiologically. Prevalence results vary quite substantially. For example, Yeo et alCitation42 in an observational study of a cohort of only 27 older (aged >70 years) individuals with COPD drawn from a single primary care practice reported that 74% of their sample had OA. In contrast, Park et al,Citation37 reporting on the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) study, nationally designed to assess the health of community-dwelling adults, found a prevalence rate of knee or hip joint OA (defined as Kellgren–Lawrence grade ≥2) in only 12% of individuals with COPD (n = 1,905; mean age = 65 years). The study by Schwab et al,Citation39 mean age 70.6 years (9.6), represented the greatest contribution to the overall weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD (23%) because of its large sample size of 52,643.

Smoking status varied significantly across the studies. These differences add to the heterogeneity noted in cohort characteristics and may have influenced the findings of this review. There is some evidence to suggest that smoking may be associated with a lower risk of developing OA,Citation44–Citation46 but it is unclear as to whether this observed inverse relationship between smoking and OA is direct (caused by smoking itself) or indirect (caused by the lower body mass index [BMI] associated with smokers compared to their nonsmoker peers).Citation47 Of note, none of the included articles in this systematic review reported the prevalence of OA by smoking status.

Obesity is a major risk factor for OA.Citation22 The prevalence rates of obesity reported by only six studies varied quite substantially from 4.4% to 40.3%. In the study by Schwab et al,Citation39 less than one-fifth (19.65%) of the sample were obese.

Most studies (10/14) relied on self-reported questionnaires to establish a diagnosis with only four out of 14 articles using confirmatory diagnostic tests.Citation33,Citation37,Citation39,Citation40,Citation48,Citation49 Although the use of objectively measured vs self-reported identification of OA could impact reporting accuracy, the difference in the prevalence of OA among self-reported questionnaires and those objectively measured was not substantial (30.7% vs 37.6%).

The prevalence of OA in COPD may exceed that of the non-COPD population. For example, among more than 4,000,000 Canadians living in British Columbia,Citation50 the prevalence of OA in 2001 was 10.8% and in a studyCitation51 conducted in Malmo, Sweden, among 10,000 adults (56–64 years) radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis was 25.4%. In the study by FraminghamCitation52 and the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project,Citation53 both of which enrolled healthy adults, it was 19.2% and 27.8%, respectively. Notwithstanding study variations, we report a prevalence of OA in COPD of 35.5%.

Importantly, the shared risk factors between COPD and OA such as older age and female gender may increase the possibility of the co-occurrence of both conditions. In fact, Kopec et alCitation50 noted that age is associated with an exponential increase in OA between the age group of 20 and 50 years and a linear increase between the age group of 50 and 80 years. None of the articles in this systematic review categorized OA in COPD by the age group. The mechanism whereby OA is prevalent in COPD, whether by increased systemic inflammatory mediators, reduced skeletal muscle function or an increase in physical inactivity, remains to be established.Citation16,Citation54–Citation56

The increased prevalence of OA is not likely to be confined to COPD as it has been noted to occur frequently in other chronic conditions such as asthma, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease and depression.Citation34 However, as both COPD and OA reduce mobility, an awareness of their co-occurrence will inform management programs such as pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) which aim to improve exercise capacity and health-related quality of life. Co-occurring conditions may adversely affect PR,Citation57–Citation60 and in a prospective studyCitation58 of 316 outpatients enrolled in PR, musculoskeletal comorbidities were identified in 10.2% of participants. Their exact impact on referral, participation and completion remains unclear especially as patients with severe comorbidities may be excluded from enrollment in an exercise training program.Citation58 Of interest, notwithstanding detailed guidelines and statements on PR,Citation61,Citation62 there are no formal guidelines on the assessment and management of those with co-occurring conditions.

As PR programs move closer to being patient rather than disease focused, exercise training using endurance, resistance, flexibility and balance will be modified to focus on the specific impairments and activity limitations. For example, in the presence of lower limb comorbidities, aquatic exercise has been reported as being equally effective as land-based exercise in improving function. McNamara et alCitation63 randomized 53 individuals with COPD and lower limb comorbidities to receive either land-based or aquatic exercise and reported similar improvements in 6-minute walking distance in both groups and greater improvements in incremental shuttle walk as well as fatigue in the aquatic group.

The findings of this systematic review support the development of new pharmacological approaches in this patient population. Both COPD and OA are associated with chronic systemic inflammation, and increased levels of neutrophil elastase have been noted in COPD.Citation64–Citation67 There is emerging evidence that neutrophil elastase is associated with articular tissue destruction in inflammatory joint diseases.Citation68 Neutrophil elastase inhibitors, already used in the management of COPD, have been shown to have protective and reparative effects on joint inflammation.Citation69 Therefore, the development of new pharmacologic approaches that might slow tissue destruction and promote repair would be of great benefit to the population with coexisting COPD and OA.

This review is limited by the heterogeneity of study designs and cohort characteristics. A number of articles were of poor quality, and only English language articles were included. It was not possible to obtain information regarding the location and severity of OA or its clinical impact. The results may have been biased toward one large study,Citation39 which was responsible for approximately 23% of the overall calculated weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD. The observation that the weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD in eight studiesCitation30,Citation32,Citation36–Citation38,Citation40–Citation42 out of 14 was <1% suggests that only a few studies significantly contributed to the overall calculated average prevalence rate.

Conclusion

Accurate information on the prevalence of OA in COPD is limited by the heterogeneity of studies. However, it is a frequently co-occurring condition that an awareness of which will inform the way health care providers manage symptoms, mobility, participation and health-related quality of life in the COPD population.

Supplementary materials

Search strategies for each database

Search strategy for Medline and PsycINFO databases

lung diseases, obstructive/or bronchitis/or pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive/or bronchitis, chronic/or pulmonary emphysema/

COPD.tw

(chronic obstruct* pulmonary diseas* or chronic obstruct* respiratory diseas*).tw

1 or 2 or 3

osteoarthritis/or osteoarthritis, hip/or osteoarthritis, knee/or osteoarthritis, spine/

(osteoarthr* or arthr* or joint* degenerat*).tw

5 or 6

morbidity/or prevalence/

(common* or frequen* or comorbid* or multimorbid* or epidemio* or prevalen*).tw

8 or 9

4 and 7 and 10

Search strategy for Embase database

chronic obstructive lung disease/or obstructive airway disease/

copd.tw

(chronic obstruct* pulmonary diseas* or chronic obstruct* respiratory diseas*).tw

1 or 2 or 3

osteoarthritis/or arthritis/or degenerative disease/or osteoarthropathy/or experimental osteoarthritis/or hand osteoarthritis/or hip osteoarthritis/or knee osteoarthritis/or spondylosis/

(osteoarthr* or arthr* or joint* degenerat*).tw

5 or 6

prevalence/or epidemiological data/or epidemiology/

morbidity/

(common* or frequen* or comorbid* or multimorbid* or epidemio* or prevalen*).tw

8 or 9 or 10

4 and 7 and 11

Search strategy for CINAHL database

(MH “Lung Diseases, Obstructive+”) OR (MH “Bronchitis”) OR (MH “Emphysema”) OR (MH “Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive+”) OR (MH “Bronchitis, Chronic”)

COPD

chronic obstruct* pulmonary diseas* OR chronic obstruct* respiratory diseas*

S1 OR S2 OR S3

(MH “Osteoarthritis, Hip”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis, Knee”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis+”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis, Spine+”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis, Wrist”)

osteoarthr* OR arthritis OR arthrosis OR joint* degenerat*

S5 OR S6

(MH “Prevalence”) OR (MH “Morbidity+”)

common* or frequen* or comorbid* or multimorbid* or epidemi*

S8 OR S9

S4 AND S7 AND S10

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VestboJHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- López-CamposJLTanWSorianoJBGlobal burden of COPDRespirology2016211142326494423

- EisnerMDIribarrenCBlancPDDevelopment of disability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: beyond lung functionThorax201166210811421047868

- AgustiÀSorianoJCOPD as a systemic diseaseCOPD20085213313818415812

- AgustiAGNogueraASauledaJSalaEPonsJBusquetsXSystemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200321234736012608452

- SabitRBoltonCEEdwardsPHArterial stiffness and osteoporosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007175121259126517363772

- WoutersEIntroduction: systemic effects in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200322suppl 461s

- HolguinFFolchEReddSCManninoDMComorbidity and mortality in COPD-related hospitalizations in the United States, 1979 to 2001Chest J2005128420052011

- ManninoDMThornDSwensenAHolguinFPrevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPDEur Respir J200832496296918579551

- ScholsAMBroekhuizenRWeling-ScheepersCAWoutersEFBody composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Clin Nutr2005821535916002800

- CielenNMaesKGayan-RamirezGMusculoskeletal disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBiomed Res Int20142014117

- ChatilaWMThomashowBMMinaiOACrinerGJMakeBJComorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc20085454955518453370

- CorsonelloAIncalziRAPistelliRPedoneCBustacchiniSLattanzioFComorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCurr Opin Pulm Med201117S21S2822209926

- BarnesPCelliBSystemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20093351165118519407051

- MaltaisFDecramerMCasaburiRAn official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20141899e15e6224787074

- LitwicAEdwardsMHDennisonEMCooperCEpidemiology and burden of osteoarthritisBr Med Bull2013105118519923337796

- HaqIMurphyEDacreJOsteoarthritisPostgrad Med J20037937738312897215

- DasSFarooqiAOsteoarthritisBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol200822465767518783743

- FelsonDTLawrenceRCDieppePAOsteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factorsAnn Intern Med2000133863564611033593

- BijlsmaJBerenbaumFLafeberFOsteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practiceLancet201137797832115212621684382

- HeidariBKnee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part ICaspian J Intern Med2011220521224024017

- ForssKSStjernbergLHanssonEEOsteoarthritis and fear of physical activity – the effect of patient educationCogent Med2017411328820

- BrownDWPleasantsROharJAHealth-related quality of life and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in North CarolinaN Am J Med Sci2010226022624116

- MachadoGPGignacMABadleyEMParticipation restrictions among older adults with osteoarthritis: a mediated model of physical symptoms, activity limitations, and depressionArthritis Care Res2008591129135

- DavisMAEttingerWHNeuhausJMMallonKPKnee osteoarthritis and physical functioning: evidence from the NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup StudyJ Rheumatol19911845915982066950

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPrisma GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementPLoS Med200967e100009719621072

- ReijndersJSEhrtUWeberWEAarslandDLeentjensAFA systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord200823218318917987654

- MunnZMoolaSLisyKRiitanoDTufanaruCMethodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence dataInt J Evid Based Healthc201513314715326317388

- SchnellKWeissCOLeeTThe prevalence of clinically-relevant comorbid conditions in patients with physician-diagnosed COPD: a cross-sectional study using data from NHANES 1999–2008BMC Pulm Med20121212622695054

- WesterikJAMettingEIvan BovenJFTiersmaWKocksJWSchermerTRAssociations between chronic comorbidity and exacerbation risk in primary care patients with COPDRespir Res20171813128166777

- RaiKKJordanRESiebertWSBirmingham COPD Cohort: a cross-sectional analysis of the factors associated with the likelihood of being in paid employment among people with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171223328138233

- LeeTAPickardASBartleBWeissKBOsteoarthritis: a comorbid marker for longer life?Ann Epidemiol200717538038417462546

- GarinNKoyanagiAChatterjiSGlobal multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, multi-country studyJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201571220521426419978

- KumbhareSPleasantsROharJAStrangeCCharacteristics and prevalence of asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap in the United StatesAnn Am Thorac Soc201613680381026974689

- LalkhenHMashRMultimorbidity in non-communicable diseases in South African primary healthcareS Afr Med J2015105213413826242533

- ParkHJLeemAYLeeSHComorbidities in obstructive lung disease in Korea: data from the fourth and fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201510157126300636

- PutchaNHanMKMartinezCHthe COPDGene® InvestigatorsComorbidities of COPD have a major impact on clinical outcomes, particularly in African AmericansChronic Obstr Pulm Dis20141110525695106

- SchwabPDhamaneADHopsonSDImpact of comorbid conditions in COPD patients on health care resource utilization and costs in a predominantly Medicare populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171273528260880

- MapelDWHurleyJSFrostFJPetersenHVPicchiMACoultasDBHealth care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case-control study in a health maintenance organizationArch Intern Med2000160172653265810999980

- WijnhovenHAKriegsmanDMHesselinkAEDe HaanMSchellevisFGThe influence of co-morbidity on health-related quality of life in asthma and COPD patientsRespir Med200397546847512735662

- YeoJKarimovaGBansalSCo-morbidity in older patients with COPD – its impact on health service utilisation and quality of life, a community studyAge Ageing2006351333716364931

- KarchAVogelmeierCWelteTCOSYCONET StudyThe German COPD cohort COSYCONET: Aims, methods and descriptive analysis of the study population at baselineRespir Med2016114273727109808

- JärvholmBLewoldSMalchauHVingårdEAge, bodyweight, smoking habits and the risk of severe osteoarthritis in the hip and knee in menEur J Epidemiol200520653754216121763

- MnatzaganianGRyanPNormanPDavidsonDHillerJSmoking, body weight, physical exercise, and risk of lower limb total joint replacement in a population-based cohort of menArthritis Rheum20116382523253021748729

- SandmarkHHogstedtCLewoldSVingardEOsteoarthrosis of the knee in men and women in association with overweight, smoking, and hormone therapyAnn Rheum Dis199958315115510364912

- KangKShinJLeeJAssociation between direct and indirect smoking and osteoarthritis prevalence in Koreans: a cross-sectional studyBMJ Open201662e010062

- RadeosMCydulkaRRoweBBarrRClarkSCamargoCValidation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among patients in the EDAm J Emerg Med200927219119619371527

- BarrRHerbstmanJSpeizerFCamargoCJrValidation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nursesAm J Epidemiol200215596597111994237

- KopecJARahmanMMBerthelotJMDescriptive epidemiology of osteoarthritis in British Columbia, CanadaJ Rheumatol2007342386e9317183616

- TurkiewiczAGerhardsson de VerdierMEngstromGPrevalence of knee pain and knee OA in southern Sweden and the proportion that seeks medical careRheumatology201454582783525313145

- FelsonDThe epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis: Results from the framingham osteoarthritis studySeminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism199020342502287948

- JordanJMHelmickCGRennerJBPrevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis ProjectJ Rheumatol200734117218017216685

- ScholsAMBuurmanWAVan den BrekelASDentenerMAWoutersEFEvidence for a relation between metabolic derangements and increased levels of inflammatory mediators in a subgroup of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax19965188198248795671

- KimHCMofarrahiMHussainSNSkeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083463719281080

- EisnerMDBlancPDYelinEHCOPD as a systemic disease: impact on physical functional limitationsAm J Med2008121978979618724969

- CrisafulliECostiSLuppiFRole of comorbidities in a cohort of patients with COPD undergoing pulmonary rehabilitationThorax200863648749218203818

- CrisafulliEGorgonePVagagginiBEfficacy of standard rehabilitation in COPD outpatients with comorbiditiesEur Respir J20103651042104820413540

- WalshJRMcKeoughZJMorrisNRMetabolic disease and participant age are independent predictors of response to pulmonary rehabilitationJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev201333424925623748375

- FranssenFRochesterCComorbidities in patients with COPD and pulmonary rehabilitation: do they matter?Eur Respir Rev20142313113114124591670

- SpruitMSinghSGarveyCAn Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20131888e13e6424127811

- RochesterCVogiatzisIHollandAAn Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med2015192111373138626623686

- McNamaraRJMcKeoughZJMcKenzieDKAlisonJAWater-based exercise in COPD with physical comorbidities: a randomised controlled trialEur Respir J20134161284129122997217

- GroutasWDouDAllistonKNeutrophil elastase inhibitorsExpert Opin Ther Pat201121333935421235378

- RahmatiMMobasheriAMozafariMInflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis: A critical review of the state-of-the-art, current prospects, and future challengesBone201685819026812612

- SokoloveJLepusCRole of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: latest findings and interpretationsTher Adv Musculoskelet Dis201352779423641259

- de TorresJCordoba-LanusELópez-AguilarCC-reactive protein levels and clinically important predictive outcomes in stable COPD patientsEur Respir J200627590290716455829

- WrightHMootsRBucknallREdwardsSNeutrophil function in inflammation and inflammatory diseasesRheumatology20104991618163120338884

- MuleyMReidABotzBBölcskeiKHelyesZMcDougallJNeutrophil elastase induces inflammation and pain in mouse knee joints via activation of proteinase-activated receptor-2Br J Pharmacol2015173476677726140667