Abstract

Purpose

Current COPD management recommendations indicate that pharmacological treatment can be stepped up or down, but there are no recommendations on how to make this adjustment. We aimed to describe pharmacological prescriptions during a routine clinical visit for COPD and study the determinants of changing therapy.

Methods

EPOCONSUL is a Spanish nationwide observational cross-sectional clinical audit with prospective case recruitment including 4,508 COPD patients from outpatient respiratory clinics for a period of 12 months (May 2014–May 2015). Prescription patterns were examined in 4,448 cases and changes analyzed in stepwise backward, binomial, multivariate, logistic regression models.

Results

Patterns of prescription of inhaled therapy groups were no treatment prescribed, 124 (2.8%) cases; one or two long-acting bronchodilators (LABDs) alone, 1,502 (34.6%) cases; LABD with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs), 389 (8.6%) cases; and triple therapy cases, 2,428 (53.9%) cases. Incorrect prescriptions of inhaled therapies were observed in 261 (5.9%) cases. After the clinical visit was audited, 3,494 (77.5%) cases did not modify their therapeutic prescription, 307 (6.8%) cases had a step up, 238 (5.3%) cases had a change for a similar scheme, 182 (4.1%) cases had a step down, and 227 (5.1%) cases had other nonspecified change. Stepping-up strategies were associated with clinical presentation (chronic bronchitis, asthma-like symptoms, and exacerbations), a positive bronchodilator test, and specific inhaled medication groups. Stepping down was associated with lung function impairment, ICS containing regimens, and nonexacerbator phenotype.

Conclusion

The EPOCONSUL study shows a comprehensive evaluation of pharmacological treatments in COPD care, highlighting strengths and weaknesses, to help us understand how physicians use available drugs.

Introduction

Several studies have consistently shown that drug prescribed for the treatment of COPD differs markedly from that recommended in current recommendation documents.Citation1,Citation2 In brief, the different available studies indicate that there is an overprescription of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs), an underutilization of long-acting bronchodilators (LABDs), a use of oral treatments not always according to their formal indications, and a drug use in disagreement with different patient types.Citation3–Citation8

Despite the valuable information these studies provide, they are frequently based on automated databases that do not allow to understand the determinants of pharmacological prescription in daily clinical practice. Although some previous studies have assessed this aspect,Citation6,Citation7,Citation9,Citation10 most of these studies are conducted in primary care and evaluate only partial aspects of drug prescription. Accordingly, there is a need for a prospective, comprehensive evaluation on what are the key elements on which physicians base their therapeutic decisions in secondary care.

In this context, clinical audits have emerged as a new tool with potentials for describing the clinical behavior in a determined clinical context, time, and geographical area, with the potential of analyzing the determinants that explain this clinical behavior, and designing a feedback strategy with the final aim to improving health care.Citation11 COPD is a common, severe, and disabling condition but a preventable and treatable disease, and it has recently been assessed in clinical audits with the aim to highlight areas of improvement in daily clinical practice. Several recent initiatives have given valuable data on how COPD is delivered to patients in different clinical scenarios.Citation12–Citation14

Regarding pharmacological prescription in secondary care outpatients, a recent pilot clinical audit evaluated clinical performance of pulmonologists in COPD outpatients.Citation15 This audit highlighted the variability in medical prescriptions for COPD in pulmonologists’ outpatient clinics,Citation16 showing the patterns of prescriptions and the determinants that led to treatment changes. However, the sample size was limited and the authors suggested that a nationwide analysis would be needed to confirm the results.

EPOCONSUL is a nationwide clinical audit aiming at evaluating clinical care delivered to COPD patients and describing the degree of adjustment to clinical guides in the outpatient secondary care setting.Citation17 By using the EPOCONSUL database, we aimed to describe pharmacological prescriptions (inhaled and oral) during a routine clinical visit for COPD, understand the distribution in different patient types, and study the determinants of changing therapy in daily clinical practice. The results of the analysis might help clinical and health care managers to understand medical prescription and improve clinical care in COPD patients.

Methods

The methodology of EPOCONSUL has been thoroughly reported previously.Citation17 Briefly, EPOCONSUL is a clinical audit that evaluates health care for outpatients with COPD in the field of specialized outpatient clinics of pneumology. It is, therefore, an observational study with prospective case recruitment and cross-sectional analysis. The sample was selected from May 2014 to May 2015 from patients seen in an outpatient clinic of the participating centers. The recruitment of patients was prospective. With the idea of having information on the whole year, the inclusion was made in bimonthly periods. At the beginning of each of these bimonthly periods, each researcher included the first 10 patients in the clinic who had an established diagnosis of COPD and who were being followed up by this outpatient clinic. Inclusion criteria required patients to have a confirmed diagnosis of COPD, including being smokers or ex-smokers with an exposure of at least 10 pack-years, >40 years old, and presenting with chronic respiratory symptoms suggestive of COPD together with a nonreversible bronchial obstruction by performing a postbronchodilator spirometry with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio <0.7. In those cases, where no broncho-reversibility tests were available, it was also accepted as diagnostic criteria to have an FEV1/FVC ratio of <0.7, together with an FEV1 value of <80%. The project considered to exclude patients who had a follow-up time of <1 year and patients who were already actively participating in another COPD-related research project. All the information during the audit was historical for the data on the clinical performance. However, the information regarding hospital resources was concurrent.

The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the San Carlos Clinical Hospital (Madrid, Spain, internal code 14/030-E). This approval certified that the present study complied with the ethical principles formulated in the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, it considered the preservation of the confidentiality of patient data as an important pillar. The protocol was also approved by the local ethics committee of each participating hospital. Currently, research laws in Spain (the Biomedical Research Act of 2007 and the Data Protection Act of 1999) explicitly state that individual consent is not necessary for retrospective evaluations of data obtained from routine clinical care for audit and research purposes, as in our study. For this reason, the signing of written informed consent by the included patients was not required. Likewise, the audited physicians were not informed about the clinical audit in order to preserve the usual clinical practice and the blinding of the clinical performance evaluation. The patient’s data were coded, and their confidentiality was conserved in accordance with Spanish laws. The Scientific Committee had the responsibility to guarantee the scientific and methodological precision of the study and the quality control of all the collected data.

For the present study, prescription patterns were analyzed. Inhaled treatment plans were divided into six categories: those patients with no prescriptions of any inhaled medication, treatment with one LABD, treatment with ICS alone, two LABD, LABD–ICS therapies, and triple therapy (long-acting muscarinic antagonists [LAMA] + long-acting beta 2 agonists [LABA] + ICS). Since the efficacy of inhaled drugs has been shown to be similar regardless of the administration in single or different inhalers,Citation18–Citation21 we considered these groups when prescribed together in one single inhaler or not. Asthma–COPD overlap was defined as in the Spanish National COPD Guideline (GesEPOC).Citation22

Incorrect therapeutic schemes were also explored. Since the current Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 A–D patient type classification is not specific enough to evaluate the correctness of a prescription at the patient level,Citation23 we identified incorrect prescriptions as those B–D patients not receiving LABD, patients receiving ICS alone, or those with same-class medications in different inhalers.

During the audited clinical visit, treatments that patients were receiving before the visit and changes taken after the visit were noted. Treatment changes were noted according to the following groups: cases with no change in the therapeutic scheme, step-up therapies, changes for a similar therapeutic scheme, and step-down changes. Step-up and -down changes were focused on three aspects: modifying the number or dose of LABD, modifying the number or dose of ICS, modifying the prescription of roflumilast, and other nonspecified changes not specifically recorded.

Statistics

Statistical computations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analysis was summarized by using the absolute (relative) frequencies of the categories for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) for numerical ones. The variability was expressed as interhospital range (IHR), expressing the maximal and minimal average value in every participating center. By showing the maximal and minimal average value, information on the variability of the different parameters evaluated by the center was provided. The significance of this variability was explored by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or the chi-squared test depending on the nature of the variable.

The description of the inhaled therapeutic groups was referred to the complete cohort; however, the prescription of the oral therapies was referred to the population in each inhaled therapy group. A description of the therapeutic changes was done by showing the percentages of cases stepping-up or stepping-down, with these percentages being referred to both the whole cohort and the number of subjects within each therapeutic option. Factors associated with stepping-up or stepping-down were explored as covariates in a bivariate analysis using unpaired t-test or chi-squared test depending on the nature of the variable. These significant associations were entered in a stepwise backward, binomial, multivariate, logistic regression model. Two models were built with step up and step down as the dependent variables. Results were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Alpha error was set at 0.05.

Results

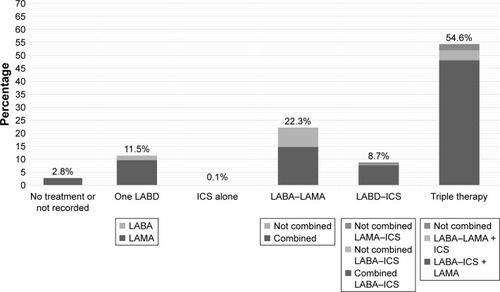

The EPOCONSUL cohort was composed of 4,508 COPD patients. The characteristics of the patients in the cohort have been previously reported.Citation17 For the present analysis, 60 cases were excluded due to having inconsistent data regarding pharmacological therapies. Therefore, 4,448 cases formed our population sample (). The prescription of the different inhaled therapy groups in the cohort is shown in and distributed as follows: no treatment prescribed or recorded, 124 cases (2.8%; IHR: 0%–36.7%; p < 0.001); one LABD, 511 cases (11.5%; IHR: 0%–33.3%; p < 0.001); ICS alone, five cases (0.1%; IHR: 0%–3.2%; p = 0.210); two LABD, 991 cases (22.3%; IHR: 8.3%–72.6%; p < 0.001); LABD–ICS, 389 cases (8.6%; IHR: 0%–26.9%; p < 0.001); and triple therapy, 2,428 cases (53.9%; IHR: 0%–78.7%; p < 0.001). Altogether, 1,502 cases (34.6%; IHR: 13.3%–100%; p < 0.001) received LABD therapy (one or two LABD) without ICS and 2,822 cases (62.6%; IHR: 9.5%–85.0%; p < 0.001) received any form of ICS. Interestingly, 36 (0.8% in the complete cohort; 9.3% in those receiving LABD–ICS therapy) cases were receiving a combination of an LAMA and an ICS, 107 (2.4% in the complete cohort; 4.4% in those receiving triple therapy) cases were receiving triple therapy with all the three drugs in different inhalers, and 332 (7.5% in the complete cohort; 33.5% in those receiving double bronchodilator therapy) cases were receiving two bronchodilators in different inhalers.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of COPD participants

Figure 1 Distribution of inhaled treatments in the EPOCONSUL cohort.

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta 2 agonists; LABD, long-acting bronchodilator; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists.

Incorrect prescriptions of inhaled therapies were observed in 261 cases (5.9%; IHR: 0%–55.0%; p < 0.001): 25 cases (0.6%; IHR: 0%–14.3%; p < 0.001) due to not receiving LABD in GOLD B–D patients, 5 cases (0.1; IHR: 0%–3.2%; p < 0.001) due to receiving ICS alone, and 231 cases (5.2%; IHR: 0%–55.0%; p < 0.001) for receiving duplicate therapies.

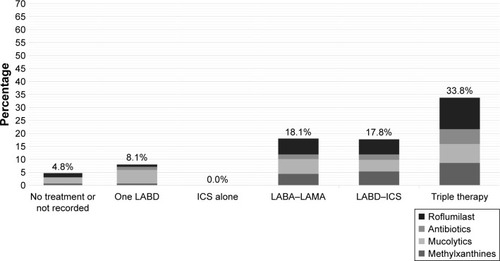

The prescription of oral treatments is shown in and was distributed as follows (percentages referred to the complete cohort): roflumilast 383 (8.6%; IHR: 0%–31.0%; p < 0.001), methylxanthines 282 (6.3%; IHR: 0%–23.2%; p < 0.001), mucolytics 277 (6.2%; IHR: 0%–31.0%; p < 0.001), and antibiotics 174 (3.9%; IHR: 0%–20.0%; p < 0.001). The distribution of oral therapies according to the inhaled therapy groups is summarized in . There was some overlap in the prescription of oral therapies, but this was <1% in all patient types, inhaled medication groups, and oral combinations (data not shown).

Figure 2 Distribution of oral treatments in the EPOCONSUL cohort.

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta 2 agonists; LABD, long-acting bronchodilator; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists.

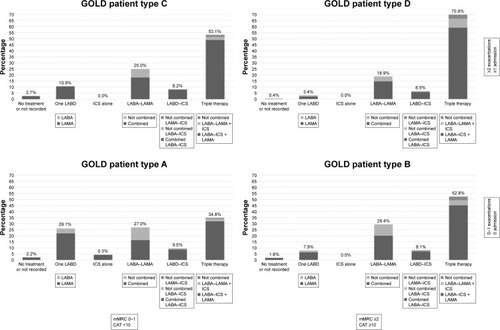

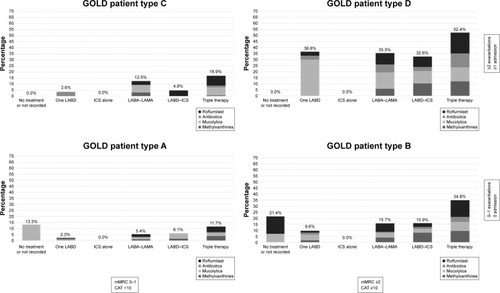

GOLD patient types were available in 2,613 cases: 681 (15.3%) GOLD A, 782 (17.7%) GOLD B, 256 (5.7%) GOLD C, and 894 (20.0%) GOLD D. The distribution of inhaled and oral therapies according to GOLD 2017 A–D patient groups is summarized in and . Triple therapy was the leading treatment in all GOLD 2017 patient types, followed by double bronchodilator therapy. In GOLD A patients, single bronchodilation and double bronchodilation were close and not far from triple therapies. In the rest of the GOLD 2017 patient types, there was a progressive increase in triple therapy and a progressive decrease in double bronchodilation. Regarding oral therapies, mucolytics were more frequently used in patients with a lower intensity of inhaled therapies, whereas usage of roflumilast increased in more severe cases.

Figure 3 Distribution of inhaled treatments in the EPOCONSUL cohort according to GOLD 2017 patient types A–D.

Note: Percentages refer to the complete cohort.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; GOLD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta 2 agonists; LABD, long-acting bronchodilator; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council scale.

Figure 4 Distribution of oral therapies in the EPOCONSUL cohort according patient groups by GOLD 2017 patient types A–D.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; GOLD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta 2 agonists; LABD, long-acting bronchodilator; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonistsm; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council scale.

Treatment changes during the audited visit are summarized in . After the clinical visit audited, 3,494 cases (77.5%; IHR: 3.3%–98.4%; p < 0.001) did not modify their therapeutic prescription, 307 cases (6.8%; IHR: 0%–66.7%; p < 0.001) had a step up, 238 cases (5.3%; IHR: 0%–26.7%; p < 0.001) had a change for a similar scheme, 182 cases (4.1%; IHR: 0%–25.0%; p < 0.001) had a step down, and 227 cases (5.1%; IHR: 0%–25.0%; p < 0.001) had other nonspecified change.

Table 2 Description of treatment changes during the audited visit

Bivariate associations of clinical variables with step up or step down of therapy are shown in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. The multivariate analysis for stepping up is presented in . Clinical presentation, a positive response in the bronchodilator test, and previous triple therapy were significantly associated with stepping up. The multivariate analysis for stepping down is presented in . Exacerbations, previous treatment with LABD–ICS, and referral from secondary care were associated with stepping down. Interestingly, lung function was not found to be significantly associated.

Table 3 Multivariate analysis with factors associated with stepping up

Table 4 Multivariate analysis with factors associated with stepping down

Discussion

Ours is the first nationwide clinical audit performed in Spain in specialized pulmonary outpatient clinics evaluating patterns of pharmacological prescription in COPD. The results of our analysis show that triple therapy continues being the most frequently prescribed pattern of medication and that the majority of prescribers do not modify therapeutic regimes in COPD patients after a routine clinical visit.

Clinical audits are complex processes framed in the concept of continuous improvement of the quality of care. These processes seek to improve patient care and its results through cyclical clinical practice evaluation strategies and results compared with recognized standards, subsequently completed through a process of implementing improvements.Citation24 According to current understanding, it is expected that health care professionals are able to receive comments on the performance of their usual practice. Although it might seem intuitive that a professional would be prone to modify their daily activities in the light of an evaluation of their quality of care, the real relevance of these changes may not have a great impact on clinical outcomes.Citation25 In this sense, one of the great remnants of clinical audits refers to the maintenance over time of this improvement achieved in clinical performance. From this idea, there is a need to establish continuous improvement strategies complemented with feedback that allow the establishment of clinical implementation programs.Citation26 Until now, the evaluation of clinical performance in COPD had focused on the hospitalized patient due to an exacerbation of the disease, probably because it is a potentially serious situation with important clinical repercussions for the patient and the health system. However, the situation in outpatient clinics has received much less attention.Citation15 Consequently, in the present study, the objective of the work was to advance in the assessment of quality assistance in the field of specialized external care and during a typical follow-up clinical visit.

The main strengths of our study are a nationwide coverage and a comprehensive, systematic evaluation of clinically relevant parameters together with resources and organizational aspects of clinical care. However, several methodological considerations must be observed in order to interpret our results correctly. In the first place, it is important to keep in mind that the clinical guidelines summarize the main norms for the diagnosis and treatment of a process. However, these are general recommendations that are not always based on evidence and do not always conform to all possible clinical presentations of the diseases. Therefore, it is usually common to find some kind of deviation from the recommendations in actual daily clinical practice. As a note, the degree of deviation from this general rule has not been quantified. Second, it is necessary to remember that a clinical audit evaluates the clinical information that a health personnel records in the clinical record. Therefore, an audit cannot identify measures carried out and that are not recorded in the clinical record. A clear example of this situation could be an evaluation of the inhalation technique that has been performed, but it has not been noted. In this regard, it is important to highlight the need to record all clinical actions with the goal that any health professional has all the relevant information available in the medical record. Third, this audit has had a cross-sectional analysis without evaluating the long-term clinical data. These data will undoubtedly serve as a basis for authors of the future audits to know the points on which to act and to study their long-term clinical impact. Likewise, the prospective impact of the adherence of the guide on the results should be another aspect of future evaluation in terms of rates of exacerbations and survival. In 2.8% of cases, there was no information on maintenance inhaled therapies. This finding has been previously reported, but with a considerable difference. A recent analysis of the medical records of 3,376 patients from general practice in Denmark revealed that 74.4% of them did not receive any maintenance inhaled medication even after spirometric confirmation of COPD.Citation27 In the UK, 28% of 20,154 patients, whose medical records were analyzed, in one studyCitation6 and 20% of 29,815 patients in another studyCitation7 received no initial pharmacological treatment. In Sweden, this figure was far below 10% in secondary care.Citation3 In the US, it has been reported that 55% of such patients did not receive inhaled maintenance therapy.Citation28 The reasons for this underprescription of maintenance inhaled therapies in COPD patients fall outside the scope of the present study and would require an ad hoc investigation, but could be partially explained by the type of center and the type of outpatient clinic available in these centers evaluating patients with specific characteristics.

Triple therapy keeps being the most prescribed medication even in A and B COPD patient types. Previous studies have highlighted the overuse of ICS and, in particular, triple therapy in COPD.Citation4,Citation5,Citation29 Although still high, the proportion of COPD patients with ICS has not been greatly reduced with previous studies reporting ICS use iñ60%Citation30 compared to 62.6% in our cohort. Indeed, it has been reported that only half of patients receiving ICS are doing this correctly prescribed.Citation31 Interestingly, the overprescription of triple therapy has been described in all clinical settings, primary and secondary care, different countries, and health systems. In our view, there are two reasons why this might be happening: 1) either we all do it wrongly in all countries and settings or 2) the guideline recommendations do not capture the complexity of the COPD patients, and there are other variables beyond lung function, symptoms, and exacerbations that influence clinicians in their medical decisions. Unfortunately, we do not have studies that can differentiate these two aspects of this controversy. Of note, one significant association with stepping down was the use of LABD–ICS, but not triple therapy, which might reflect a change in the clinical behavior of clinicians. In this regard, the variables associated with stepping up could reflect a trend toward a more personalized medicine in COPD in secondary care.

Duplicate therapies were the most frequently found error in inhaled medication prescription. In the present study, we were able to detect duplicated medications, ie, same-class repeats (eg, LABA–LAMA + ICS–LABA, LABA–LAMA + LABA, or LABA–ICS + ICS). Fortunately, the implementation of electronic prescription in Spain will probably help clinicians to correct all these prescriptions.Citation32

After the clinical visit audited, 3,494 (77.5%) cases did not modify their therapeutic prescription. This result has been reported previously for our country. In a recent pilot clinical audit carried out in Spain, 64.8% cases saw no change in pharmacological treatment.Citation16 The high number of cases in which no drug prescribing modifications are carried out is another interesting debate. These are probably well-controlled patients with no exacerbations and few symptoms, and accordingly, we need to establish whether, when, and how in these cases a step down could be tried.Citation33 Although current recommendation documents suggest that stepping down can now be considered, currently there is no universally accepted consensus on how to perform this at the patient level.

Conclusion

Ours is the first nationwide clinical audit performed in specialized pulmonary outpatient clinics evaluating pharmacological prescriptions in COPD. The results of our analysis show that the majority of chest physicians do not modify COPD therapeutic regimes after a routine clinical visit. Triple therapy in different inhalers continues being the most frequently prescribed medication pattern. The study highlights determinants of medical prescription in COPD, which require further research.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the present work want to show their sincere gratitude to all the researchers of the EPOCONSUL study for the extraordinary and tireless field work (a list of the EPOCONSUL researchers is available in the Supplementary materials). This study has been promoted and sponsored by the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR). The authors thank Boehringer Ingelheim for its financial support to carry out the study. The financing entities did not participate in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, publication, or preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure

JLLC has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies, and writing publications for (alphabetical order) Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cantabria Pharma, Chiesi, Esteve, Faes, Ferrer, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Rovi, Teva, and Takeda. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VogelmeierCFCrinerGJMartinezFJGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195555758228128970

- MiravitllesMSoler-CatalunaJJCalleMSpanish guidelines for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (GesEPOC) 2017. Pharmacological treatment of stable phaseArch Bronconeumol201753632433528477954

- SundhJJansonCJohanssonGCharacterization of secondary care for COPD in SwedenEur Clin Respir J201741127007928326177

- SimeoneJCLuthraRKailaSInitiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the USInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201712738328053518

- MapelDLaliberteFRobertsMHA retrospective study to assess clinical characteristics and time to initiation of open-triple therapy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, newly established on long-acting mono- or combination therapyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017121825183628684905

- Gruffydd-JonesKBrusselleGJonesRChanges in initial COPD treatment choice over time and factors influencing prescribing decisions in UK primary care: in UK primary care: a real-world, retrospective, observationalNPJ Prim Care Respir Med2016261600228358398

- ChalmersJDTebbothAGayleATernouthARamscarNDeterminants of initial inhaled corticosteroid use in patients with GOLD A/B COPD: a retrospective study of UK general practiceNPJ Prim Care Respir Med20172714328663549

- DingBSmallMTreatment trends in patients with asthma-COPD overlap syndrome in a COPD cohort: findings from a real-world surveyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017121753176328670116

- SouliotisKKaniCPapageorgiouMLionisDGourgoulianisKUsing big data to assess prescribing patterns in Greece: the case of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePLoS One2016115e015496027191724

- Roman-RodriguezMvan BovenJFVargasFFactors associated with inhaled corticosteroids prescription in primary care patients with COPD: a cross-sectional study in the Balearic Islands (Spain)Eur J Gen Pract201622423223927597172

- HaycockCSchandlAA new tool for quality: the internal auditNurs Adm Q201741432132728859000

- RuparelMLopez-CamposJLCastro-AcostaAHartlSPozo-RodriguezFRobertsCMUnderstanding variation in length of hospital stay for COPD exacerbation: European COPD auditERJ Open Res201621pii00034-2015

- SpruitMAPittaFGarveyCERS Rehabilitation and Chronic Care, and Physiotherapists Scientific Groups, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, ATS Pulmonary Rehabilitation Assembly and the ERS COPD Audit TeamDifferences in content and organisational aspects of pulmonary rehabilitation programmesEur Respir J20144351326133724337043

- RobertsCMLopez-CamposJLPozo-RodriguezFHartlSEuropean COPD Audit TeamEuropean hospital adherence to GOLD recommendations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation admissionsThorax201368121169117123729193

- Lopez-CamposJLAbad ArranzMCalero AcunaCClinical audits in outpatient clinics for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: methodological considerations and workflowPLoS One20151011e014185626544556

- Lopez-CamposJLAbad ArranzMCalero AcunaCDeterminants for changing the treatment of COPD: a regression analysis from a clinical auditInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016111171117827330285

- Calle RubioMAlcazar NavarreteBSorianoJBClinical audit of COPD in outpatient respiratory clinics in Spain: the EPOCONSUL studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171241742628182155

- DahlRJadayelDAlagappanVKChenHBanerjiDEfficacy and safety of QVA149 compared to the concurrent administration of its monocomponents indacaterol and glycopyrronium: the BEACON studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2013850150824159259

- HagedornCKassnerFBanikNNtampakasPFielderKInfluence of salmeterol/fluticasone via single versus separate inhalers on exacerbations in severe/very severe COPDRespir Med2013107454254923337300

- VestboJPapiACorradiMSingle inhaler extrafine triple therapy versus long-acting muscarinic antagonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRINITY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trialLancet2017389100821919192928385353

- BremnerPRBirkRBrealeyNIsmailaASZhuCQLipsonDASingle-inhaler fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol versus fluticasone furoate/vilanterol plus umeclidinium using two inhalers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized non-inferiority studyRespir Res20181911929370819

- MiravitllesMSoler-CatalunaJJCalleMSpanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC): pharmacological treatment of stable COPD. Spanish society of pulmonology and thoracic surgeryArch Bronconeumol201248724725722561012

- SorianoJBLamprechtBRamirezASMortality prediction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease comparing the GOLD 2007 and 2011 staging systems: a pooled analysis of individual patient dataLancet Respir Med20153644345025995071

- CalabroGEDe WaureCMoginiVClinical audit as a quality improvement tool in the emergency setting. A systematic review of the literatureIg Sanita Pubbl201672544347928068677

- Lopez-CamposJLAsensio-CruzMICastro-AcostaACaleroCPozo-RodriguezFAUDIPOC and the European COPD Audit StudiesResults from an audit feedback strategy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in-hospital care: a joint analysis from the AUDIPOC and European COPD audit studiesPLoS One2014910e11039425333953

- StephensonMMcArthurAGilesKLockwoodCAromatarisEPearsonAPrevention of falls in acute hospital settings: a multi-site audit and best practice implementation projectInt J Qual Health Care2016281929826678803

- GottliebVLyngsoAMSaebyeDFrolichABackerVThe use of COPD maintenance therapy following spirometry in general practiceEur Clin Respir J Epub2016622

- DietteGBDalalAAD’SouzaAOLunacsekOENagarSPTreatment patterns of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in employed adults in the United StatesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20151041542225759574

- BrusselleGPriceDGruffydd-JonesKThe inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UKInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102207221726527869

- PriceDWestDBrusselleGManagement of COPD in the UK primary-care setting: an analysis of real-life prescribing patternsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014988990425210450

- FalkJDikNBugdenSAn evaluation of early medication use for COPD: a population-based cohort studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016113101310827994449

- Lizano-DiezIModamioPLopez-CalahorraPEvaluation of electronic prescription implementation in polymedicated users of Catalonia, Spain: a population-based longitudinal studyBMJ Open2014411e006177

- MagnussenHWatzHKirstenAStepwise withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD patients receiving dual bronchodilation: WISDOM study design and rationaleRespir Med2014108459359924477080