Abstract

Purpose

Previous studies have shown that progressive forms of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) occur frequently in patients with obstructive lung disease (OLD). However, few studies have written about this relationship. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between OLD and NAFLD.

Subjects and methods

The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey is a national population-based, cross-sectional surveillance program that was initiated to assess the health and nutritional status of the Korean population. From 2007 to 2010, 11,738 subjects were enrolled. The subjects were defined as having NAFLD when they had scores higher than −0.640 in a NAFLD liver fat score prediction model, which was a previously validated prediction score. Individuals with forced expiratory volume in one second/forced vital capacity <0.7 were considered to have OLD. The subjects were divided into non-OLD and OLD groups and non-NAFLD and NAFLD groups. All analyses were performed using sample weighting using the complex samples plan.

Results

The prevalences of NAFLD and OLD were 30.2% and 8.9%, respectively. Although not statistically significant, subjects in the NAFLD group involved a higher tendency of having OLD than did those in the non-NAFLD group (8.5% vs 10.0%, respectively, P=0.060). Subjects with OLD showed a higher tendency to have NAFLD than non-OLD subjects (30.0% vs 33.7%, respectively, P=0.060). NAFLD subjects were at higher odds of OLD (odds ratio=1.334; 95% confidence interval=1.108–1.607, P=0.002) than non-NAFLD subjects, after adjusting for age, sex, and smoking history. OLD subjects were at higher odds of NAFLD (odds ratio=1.556; 95% confidence interval=1.288–1.879, P<0.001) than non-OLD subjects, after adjusting for age, sex, and smoking history.

Conclusion

This study showed that NAFLD is related to OLD. Clinicians should be aware of possible liver comorbidities in OLD patients and that extrahepatic disease in NAFLD patients may vary more than previously thought.

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by hepatic triglyceride accumulation, known as steatosis, and the absence of significant alcohol consumption or secondary causes (eg, viral hepatitis).Citation1 Stemming from overnutrition and less physical activity, NAFLD has become the most common form of chronic liver damage. Increased prevalences of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome have been recorded in developed and developing countries, drawing concern.Citation2 NAFLD has been considered a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and is associated with various metabolic abnormalities, including hyperlipidemia, central obesity, type 2 diabetes, and the development of cardiovascular disease.Citation3–Citation5

Obstructive lung disease (OLD) is a category of respiratory disease characterized by airway obstruction.Citation6 In patients with OLD, including those with COPD, metabolic syndrome occurs frequently.Citation7 Emerging evidence shows that pulmonary function impairment is connected not only with cigarette smoking but also with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance, all of which are linked to increased oxidative stress and chronic, low-grade inflammation.Citation8–Citation10 Additionally, prospective studies have documented that pulmonary function impairment is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease-related morbidity and mortality.Citation11,Citation12

Few studies have reported the relationship between NAFLD and impaired lung function. Lonardo et alCitation13 believed that there is strong epidemiological and clinical evidence supporting the notion that NAFLD and COPD, which are highly prevalent, non-communicable, lifestyle-related systemic disorders primarily clustered in the metabolic and cardiovascular area with a similar pathogenic background and a high comorbidity rate, are related not by chance but also by pathobiological necessity. However, this relationship has not been evaluated thoroughly. We performed a Korean population-based study to evaluate the relationship between NAFLD and OLD. We aimed to evaluate whether 1) individuals with NAFLD are at higher odds of developing OLD than non-NAFLD individuals and 2) individuals with OLD are at higher odds of developing NAFLD than non-OLD individuals.

Subjects and methods

Study subjects

The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) is a national population-based, cross-sectional surveillance program that uses stratified random sampling to assess the health and nutritional status of Korean people.Citation14 The Korea Centers of Disease Control and Prevention performed this survey to obtain statistically reliable and representative data; patients in nursing homes, soldiers, prisoners, and foreigners were excluded. A stratified, multistage probability sampling design, considering location and residence type, was used in the KNHANES to establish nationwide representativeness. The KNHANES database is publicly available at the KNHANES website (http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/eng; available in English).

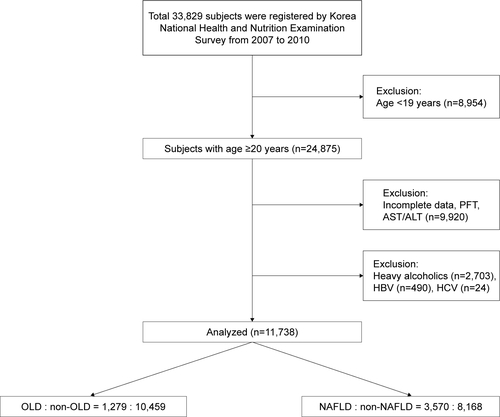

A flow diagram of the subjects who were included in this study is depicted in Figure S1. Among the 33,829 subjects with data in the KNHANES, 2007–2010, we selected those aged ≥20 years (24,875 subjects), since pulmonary function tests were performed for subjects aged ≥20 years. Cross-sectional surveys that were conducted over a period of 4 years were pooled for analysis. Subjects with missing data for pulmonary function test, liver function test, alcoholic consumption, or hepatitis viral test were excluded (n=9,920). Additionally, subjects who met the following criteria based on our protocol were excluded: 1) alcohol consumption >140 g/week for men and >70 g/week for women (n=2,703) and 2) positivity for serologic markers for hepatitis B (n=490) and hepatitis C virus (n=24). Finally, 11,738 subjects were included in the analysis and divided into groups according to whether OLD and NAFLD were present.

Clinical and laboratory parameters

Information regarding age, height, body weight, waist circumference, smoking, drinking, and additional laboratory results known to be related to NAFLD or OLD was collected for all study subjects. Age was categorized into three levels: <40, 40–59, and ≥60 years. Responses to a questionnaire about smoking habits were categorized as never, past, or current. We excluded those with heavy alcohol consumption, which was defined as >140 g/week for men and >70 g/week for women.

After the subjects fasted overnight for >8 hours, blood samples were drawn from all participants during the survey, immediately refrigerated, and transported to the central testing institute (Neodin Medical Institute, Seoul, Republic of Korea). All blood samples were analyzed within 24 hours after transportation. The serum levels of lipid and liver enzyme profiles were determined using a Hitachi 8,700 automated chemistry analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) using specifically indicated methods. Spirometry data that were obtained by a qualified technician were assessed by another trained technician and the principal investigator to determine whether these data met the criteria for acceptability and reproducibility.

Hepatic steatosis and OLD definitions

NAFLD was defined using a previous validated fatty liver prediction model: NAFLD liver fat score (LFS).Citation15 Using this model, the risk score for NAFLD was determined as follows:

NAFLD LFS = −2.89 + 1.18 × metabolic syndrome (yes=1/no=0) + 0.45 × type 2 diabetes (yes=2/no=0) + 0.15 × fasting sugar-insulin (mU/L) + 0.04 × (fasting sugar-aspartate aminotransferase/fasting sugar-alanine aminotransferase).

Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the criteria of the International Diabetes FederationCitation16 (waist circumference, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure, fasting glucose); type 2 diabetes was defined according to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association.Citation17 In this prediction model, individuals with values greater than −0.640 were considered to have NAFLD.Citation15 Individuals with forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity <0.7 were considered to have OLD.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of NAFLD and non-NAFLD subjects and those of OLD and non-OLD subjects were compared using an unpaired t-test for continuous variables or the chi-squared test for categorical variables and are presented as a mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) and percentage. Continuous data were tested for data normality and variance homogeneity. To evaluate the relationship between NAFLD and OLD while controlling potential confounding factors, multiple logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratio [OR] for NAFLD and OLD. Potential confounding variables, including age, sex, smoking history, and NAFLD, were controlled in an OLD regression model. Variables, including age, sex, smoking history, and OLD, were controlled in the regression model of NAFLD. ORs and 95% CIs were calculated. Of the variables we collected, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, liver function, and body mass index (obesity) were not included in the multiple logistic regression models, because they were included in the calculation of LFS.

As the KNHANES data are collected using a complex sampling design, the survey weights are provided. All analyses were performed using sample weighting using the complex samples plan, which is available as the complex samples option in the high version of SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), to represent the total, non-institutionalized civilian population in Korea. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corporation). An adjusted P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

This study was approved annually from 2007 to 2010 by the institutional review board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (approval numbers: 2007-02CON-04-P, 2008-04EXP-01-C, 2009-01CON-03-2C, and 2010-02CON-21-C). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the amended Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from each study participant.

Results

The weighted study population comprised 23,547,091 individuals. There were 16,415,120 and 7,131,971 non-NAFLD and NAFLD subjects, respectively. Furthermore, there were 21,433,227 and 2,113,864 non-OLD and OLD subjects, respectively.

The baseline characteristics of subjects with and without NAFLD are shown in . NAFLD subjects were older than non-NAFLD subjects (45.93 vs 51.81 years, respectively, P<0.001) and had a higher body mass index (23.27 vs 26.03 kg/m2, respectively, P<0.001). The NAFLD group also had more ex-smokers (3.3% vs 5.9%, respectively, P<0.001), current smokers (31.9% vs 37.9%, respectively P<0.001), and a higher proportion of men (35.8% vs 48.3%, respectively, P<0.001) than did the non-NAFLD group. As hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome were included in the calculation of having NAFLD, subjects reported having these conditions more frequently than the non-NAFLD subjects did. NAFLD subjects showed decreased lung function, higher liver enzyme levels, and higher liver function scores than the non-NAFLD subjects. Although not statistically significant, subjects in the NAFLD group had a higher tendency to have OLD than those in the non-NAFLD group (8.5% vs 10.0%, respectively, P=0.060).

Table 1 Subject characteristics according to the presence of NAFLD

The baseline characteristics of subjects with and without OLD are shown in Table S1. OLD subjects were older than non-OLD subjects (46.08 vs 64.25 years, respectively, P<0.001). Moreover, the OLD group had more ex- (3.3% vs 11.8%, respectively, P<0.001) and current smokers (32.0% vs 51.0%, respectively, P<0.001) and a higher proportion of men (37.2% vs 63.3%, respectively, P<0.001) than the OLD group. Non-OLD subjects had a higher body mass index than the OLD subjects (24.18 vs 23.36 kg/m2, respectively, P<0.001). OLD subjects reported having hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome, which are related to NAFLD, more frequently than the non-OLD subjects did. OLD subjects showed decreased lung function, higher liver enzyme levels, and higher liver function scores than the non-OLD subjects. They also showed a higher tendency to have NAFLD than the non-OLD subjects (30.0% vs 33.7%, respectively, P=0.060).

and show the relationships between OLD and NAFLD in the logistic regression models. When age, sex, smoking status, and OLD were included in the regression model (), OLD (OR=1.556, 95% CI=1.288–1.879, P<0.001) was significantly related to NAFLD. Higher age (40–59 years: OR=1.917, 95% CI=1.682–2.185, P<0.001, and ≥60 years: OR=3.011, 95% CI=2.509–3.613, P<0.001) and male sex (OR=1.852, 95% CI=1.538–2.231, P<0.001) showed significant correlations with NAFLD. Unlike OLD, smoking status (ex-smoker: OR=0.980, 95% CI=0.808–1.189, P=0.694 and current smoker: OR=0.890, 95% CI=0.681–1.163, P=0.694) did not show a significant correlation with NAFLD.

Table 2 Logistic regression analyses of factors related to NAFLD

Table 3 Logistic regression analyses of factors related to OLD

When age, sex, smoking status, and NAFLD were included in the regression model (), NAFLD (OR=1.334, 95% CI=1.108–1.607, P=0.002) was significantly related to OLD. Higher age (40–59 years: OR=6.196, 95% CI=5.102–7.525, P<0.001 and ≥60 years: OR=27.402, 95% CI=17.135–43.820, P<0.001), male sex (OR=2.159, 95% CI=1.628–2.864, P<0.001), and smoking status (ex-smoker: OR=2.227, 95% CI=1.569–3.300, P<0.001; current smoker: OR=2.016, 95% CI=1.517–2.680, P<0.001) showed significant correlations with OLD.

Discussion

The major strength of this study is that it is a large population-based study using thoroughly collected national data, which enhances the statistical reliability of the results and our ability to generalize the data. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no studies have analyzed ORs of OLD in NAFLD subjects and ORs of NAFLD in OLD subjects in a large population-based study. Owing to the characteristics of the KNHANES, we could analyze the ORs of NAFLD and OLD subjects in both ways. By doing so, we could reveal a precise relationship between OLD and NAFLD. We demonstrated that NAFLD patients are at higher odds of developing OLD than did non-NAFLD patients and that OLD patients are at higher odds of developing NAFLD than non-OLD patients. In light of the results of this study, we suggest that physicians should be more aware of possible liver comorbidities in OLD patients and that extrahepatic disease in NAFLD patients may vary more than previously thought. Furthermore, we believe that this study could provide valuable information for future studies. The validity of the reported confounding factors was also confirmed in this study population, which supports the consistency of the present findings. Subjects of higher age,Citation18 male sex,Citation19 and smoking historyCitation18 were at higher odds of OLD, while subjects of higher age and male sexCitation20 were at higher odds of NAFLD.

In previous studies, the estimated prevalence of NAFLD was 20%–35% among the general population.Citation21 In Korea, in a study of 141,610 adults who lived in an urban area and were 18–80 years old, the prevalence of NAFLD was 27.3%.Citation22 In this study, the prevalence of NAFLD was 30.2%. The difference in the prevalences of NAFLD may be due to differences in the study population (eg, age and urban-dwelling area) and method (eg, ultrasonography and LFS). Additionally, in a previous study, the prevalence of OLD among 13,835 American adult subjects aged 19–80 years was 11.8%,Citation23 and it was 13.1% in a study of 16,151 adults in Korea aged ≥40 years.Citation24 The prevalence of OLD in this study was 8.9%. The difference may be due to the study population: we excluded subjects with hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus and those who consumed alcohol heavily.

Several previous studies have described a relationship between NAFLD and OLD. In a study of 111 subjects with COPD, Viglino et alCitation25 showed that NAFLD is highly prevalent in individuals with COPD and might contribute to cardiometabolic comorbidities. Similarly, Mapel and MartonCitation26 and Qin et alCitation27 demonstrated that subjects who have impaired lung function or are diagnosed with COPD are at a higher risk of developing NAFLD. Other studiesCitation14,Citation17,Citation28,Citation29 showed that NAFLD and liver disease patients have impaired lung function or a higher prevalence of COPD. In this context, the findings of this study verified and supported those of previous studies.

Over the last decade, it has been shown that the clinical burden of NAFLD is not only confined to liver-related morbidity and mortality but also that NAFLD is a multisystemic disease that affects the extrahepatic organs and regulatory pathways.Citation30 Excessive free fatty acids and chronic low-grade inflammation in visceral adipose tissue are considered to be two of the most important factors contributing to the progression of liver injury in NAFLD patients.Citation31 In addition, secretion of adipokines from visceral adipose tissue, as well as lipid accumulation in the liver, further promotes inflammation, which is activated by free fatty acids and contributes to insulin resistance.Citation31 Similarly, OLD patients also tend to present with multiple comorbidities more frequently than those without OLD. The most frequent comorbidities that accompany OLD include cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, osteoporosis, dysfunction of skeletal muscle, anxiety, depression, cognitive impairment, gastrointestinal diseases, and respiratory conditions, such as asthma, bronchiectasis, pulmonary fibrosis, and lung cancer.Citation7 OLD is associated with high levels of systemic inflammation, probably secondary to pulmonary inflammation.Citation20

Various inflammatory cytokines are related to NAFLD. Tumor necrosis factor alpha might play an initial role in the occurrence of steatosis, while leptin is known to have pro-steatotic and pro-fibrotic actions.Citation32 An elevation in serum levels of interleukin-8 has been observed in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisCitation33 and alcoholic liver disease.Citation34 Moreover, the involvement of oxidative stress has been confirmed in the development of NAFLD.Citation35 Inflammation and oxidative stress that cascades from NAFLD may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary function impairment. Meanwhile, Keatings et alCitation36 reported that statistically significant increases of interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha were related to the severity of airway diseases. In a rat model, Liang et alCitation37 reported that the frequency of acute exacerbation and severity of COPD were associated with a higher leptin level. Furthermore, oxidative stress is now recognized as a major predisposing factor in the pathogenesis of COPD.Citation38 As mentioned previously, these markers were also related to the pathogenesis of NAFLD. This could be a possible mechanism for the findings in this study. However, it is uncertain whether inflammation due to NAFLD would trigger OLD inflammation or whether inflammation due to OLD would trigger NAFLD inflammation. Therefore, further studies concerning the biochemical and metabolic mechanisms of these conditions are required.

This study has some limitations. First, we did not perform a liver biopsy, which is the gold standard for confirming a NAFLD diagnosis and providing prognostic information, nor did we perform ultrasonography, which is the most common diagnosis method.Citation39 However, neither method was included in the KNHANES data. Instead, we used an indirect method: the NAFLD LFS. The NAFLD LFS shows a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 71%.Citation15 To increase the accuracy of identifying NAFLD, we excluded subjects with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses and those with heavy alcohol consumption. We believe that using the NAFLD LFS was reasonable for performing an epidemiologic study to identify the relationship between NAFLD and OLD. In future studies, the combination of biomarkers/scores and transient elastography with liver ultrasonography, which were not performed in the current study, might confer additional diagnostic accuracy. Second, because a pulmonary test was not mandatory, some patients may have refused to take the pulmonary function test. In addition, patients with severe COPD may have had low survey participation. Therefore, the number of cases was possibly underestimated. Finally, this study only identified a relationship between OLD and NAFLD, but not an association between OLD and NAFLD. As this was a cross-sectional study, further studies are needed to reveal the causality between OLD and NAFLD.

Conclusion

This study showed that NAFLD is associated with OLD. Physicians should be aware of possible liver comorbidities in OLD patients and that extrahepatic disease in NAFLD patients may vary more than previously thought. Further studies concerning the biochemical and metabolic mechanisms of NAFLD and OLD are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the officers who conducted KNHANES.

Supplementary materials

Figure S1 Flow diagram of the subjects who were included in this study.

Abbreviations: PFT, pulmonary function test; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; OLD, obstructive lung disease; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Table S1 Subject characteristics according to the presence of OLD

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NascimbeniFPaisRBellentaniSFrom NAFLD in clinical practice to answers from guidelinesJ Hepatol201359485987123751754

- GagginiMMorelliMBuzzigoliEDefronzoRABugianesiEGastaldelliANon-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its connection with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis and coronary heart diseaseNutrients2013551544156023666091

- TargherGBertoliniLPoliFNonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of future cardiovascular events among type 2 diabetic patientsDiabetes200554123541354616306373

- MarchesiniGBugianesiEForlaniGNonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndromeHepatology200337491792312668987

- FanJGFarrellGCEpidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in ChinaJ Hepatol200950120421019014878

- MurgiaNObstructive lung disease: Occupational exposures smoking and airway inflammation [thesis]GöteborgGöteborgs Universitet2017

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPComorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186215516122561964

- FornoEHanYYMuzumdarRHCeledónJCInsulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and lung function in US adolescents with and without asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2015136230431125748066

- YehHCPunjabiNMWangNYCross-sectional and prospective study of lung function in adults with type 2 diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) studyDiabetes Care200831474174618056886

- LeoneNCourbonDThomasFLung function impairment and metabolic syndrome: the critical role of abdominal obesityAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179650951619136371

- EngströmGHedbladBNilssonPWollmerPBerglundGJanzonLLung function, insulin resistance and incidence of cardiovascular disease: a longitudinal cohort studyJ Intern Med2003253557458112702035

- SchroederEBWelchVLCouperDLung function and incident coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities StudyAm J Epidemiol2003158121171118114652302

- LonardoANascimbeniFPonz de LeonMNonalcoholic fatty liver disease and COPD: is it time to cross the diaphragm?Eur Respir J2017496170054628596428

- KweonSKimYJangMJData resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES)Int J Epidemiol2014431697724585853

- KotronenAPeltonenMHakkarainenAPrediction of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fat using metabolic and genetic factorsGastroenterology2009137386587219524579

- EckelRHAlbertiKGGrundySMZimmetPZThe metabolic syndromeLancet (London, England)20103759710181183

- Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitusDiabetes care201033Suppl 1S62S6920042775

- MartinezCHManninoDMJaimesFAUndiagnosed Obstructive Lung Disease in the United States. Associated Factors and Long-term MortalityAnn Am Thorac Soc201512121788179526524488

- KoperIGender-Specific Differences in Obstructive Lung DiseasesPneumologie (Stuttgart, Germany)2015696345349

- VernonGBaranovaAYounossiZMSystematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adultsAlimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics201134327428521623852

- ChalasaniNYounossiZLavineJEThe diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of GastroenterologyGastroenterology201214271592160922656328

- JeongEHJunDWChoYKRegional prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Seoul and Gyeonggi-do, KoreaClin Mol Hepatol201319326627224133664

- ParkHJLeemAYLeeSHComorbidities in obstructive lung disease in Korea: data from the fourth and fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101571158226300636

- ViglinoDJullian-DesayesIMinovesMNonalcoholic fatty liver disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J2017496160192328596431

- MapelDWMartonJPPrevalence of renal and hepatobiliary disease, laboratory abnormalities, and potentially toxic medication exposures among persons with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2013812713423515180

- QinLZhangWYangZImpaired lung function is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease independently of metabolic syndrome features in middle-aged and elderly ChineseBMC Endocrine Disorders20171711828330472

- JungDHShimJYLeeHRMoonBSParkBJLeeYJRelationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and pulmonary functionInternal medicine journal201242554154622181832

- MinakataYUedaHAkamatsuKHigh COPD prevalence in patients with liver diseaseInternal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan)2010492426872691

- ByrneCDTargherGNAFLD: a multisystem diseaseJ Hepatol2015621 SupplS47S6425920090

- MilicSLulicDStimacDNon-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity: biochemical, metabolic and clinical presentationsWorld Journal of Gastroenterology201420289330933725071327

- AndersonDMacneeWTargeted treatment in COPD: a multi-system approach for a multi-system diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009432133519750192

- PolyzosSAMantzorosCSNonalcoholic fatty future diseaseMetabolism20166581007101626805015

- KugelmasMHillDBVivianBMarsanoLMcClainCJCytokines and NASH: a pilot study of the effects of lifestyle modification and vitamin EHepatology200338241341912883485

- HuangYSChanCYWuJCPaiCHChaoYLeeSDSerum levels of interleukin-8 in alcoholic liver disease: relationship with disease stage, biochemical parameters and survivalJ Hepatol19962443773848738722

- SumidaYNikiENaitoYYoshikawaTInvolvement of free radicals and oxidative stress in NAFLD/NASHFree Radical Research2013471186988024004441

- KeatingsVMCollinsPDScottDMBarnesPJDifferences in interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in induced sputum from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med199615325305348564092

- LiangRZhangWSongYMLevels of leptin and IL-6 in lungs and blood are associated with the severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients and rat modelsMol Med Rep2013751470147623525184

- KirkhamPABarnesPJOxidative stress in COPDChest2013144126627323880677

- HashimotoETaniaiMTokushigeKCharacteristics and diagnosis of NAFLD/NASHJ Gastroenterol Hepatol201328Suppl 4647024251707