Abstract

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) reduces the number and duration of hospital admissions and readmissions, and improves health-related quality of life in patients with COPD. Despite clinical guideline recommendations, under-referral and limited uptake to PR contribute to poor treatment access. We reviewed published literature on the effectiveness of interventions to improve referral to and uptake of PR in patients with COPD when compared to standard care, alternative interventions, or no intervention. The review followed recognized methods. Search terms included “pulmonary rehabilitation” AND “referral” OR “uptake” applied to MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ASSIA, BNI, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library up to January 2018. Titles, abstracts, and full papers were reviewed independently and quality appraised. The protocol was registered (PROSPERO # 2016:CRD42016043762). We screened 5,328 references. Fourteen papers met the inclusion criteria. Ten assessed referral and five assessed uptake (46,146 patients, 409 clinicians, 82 hospital departments, 122 general practices). One was a systematic review which assessed uptake. Designs, interventions, and scope of studies were diverse, often part of multifaceted evidence-based management of COPD. Examples included computer-based prompts at practice nurse review, patient information, clinician education, and financial incentives. Four studies reported statistically significant improvements in referral (range 3.5%–36%). Two studies reported statistically significant increases in uptake (range 18%–21.5%). Most studies had methodological and reporting limitations. Meta-analysis was not conducted due to heterogeneity of study designs. This review demonstrates the range of approaches aimed at increasing referral and uptake to PR but identifies limited evidence of effectiveness due to the heterogeneity and limitations of study designs. Research using robust methods with clear descriptions of intervention, setting, and target population is required to optimize access to PR across a range of settings.

Introduction

COPD presents a considerable health challenge. It is estimated that worldwide 328 million people have COPD and 65 million people live with moderate to severe COPD.Citation1 In 2015, COPD accounted for 5% of all deaths globally,Citation2 and in the UK, ~1.2 million people and 4.5% of all people aged over 40 years live with the condition.Citation3 COPD is likely to be underdiagnosed and prevalence in the UK may be rising.Citation3 It compromises individuals’ quality of life and impacts healthcare costs, mostly relating to hospital admissions. In 2012, it was estimated to cost the UK National Health Service £800 million per annum.Citation4 Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), providing supervised exercise and education, improves COPD symptoms leading to improvements in exercise capacity and quality of life.Citation5 PR reduces the number and duration of respiratory hospital admissions experienced by individuals,Citation6 the number of readmissions,Citation6,Citation7 and can foster self-management skills.Citation8 It is a cost-effective treatment.Citation9

Despite a clear evidence base and guidelines recommending PR,Citation10,Citation11 it is grossly underutilized in practice worldwide.Citation12 In England and Wales, for example, the National COPD Audit Programme for 2013/14 estimated the prevalence of COPD patients eligible for PR to be 446,000; however, only 68,000 were referred (15% of normative need) of whom only 69% attended an initial assessment (10% of normative need).Citation13 Utilization may be impacted by availability, referral, and uptake but even where places are available they may not be utilized. In the East of England in 2014/15, the number of available PR places represented only 53.8% of the proposed target, but just 73% of these places were taken up.Citation14 There is an urgent need to improve referral and uptake to PR both in the UKCitation6,Citation13 and globallyCitation12 but there is no best practice guidance for doing so.

We set out to conduct a systematic review of published studies on the effectiveness of interventions to increase rates of referral and uptake from primary care or outpatient departments to exercise-based PR programs in patients with COPD compared to standard care, alternative interventions, or no intervention.

Methods

Recognized systematic review methodsCitation15 were adapted to conduct the review. The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (2016:CRD42016043762)Citation16 and reported according to PRISMA guidelines.Citation17

Eligibility

Studies were required to report at least one of the main outcomes of interest: rates of referral to or uptake of exercise-based PR programs in patients with COPD. We defined PR programs as including “multicomponent, multidisciplinary interventions, which are tailored to the individual patient’s needs. The rehabilitation process should incorporate a program of physical training, disease education, and nutritional, psychological, and behavioral intervention.”Citation18 Uptake was defined as having attended a first appointment with a PR provider including initial assessment.

We included all studies that used established quantitative or mixed methods of data collection, eg, trials, surveys, direct observations, action research, interviews, focus groups or questionnaires, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. Interventions could be contrasted with standard care, alternative interventions, or have no comparator or control.

We included studies of i) healthcare professionals who referred COPD patients to PR in primary, secondary, or community care settings; ii) adult patients (≥18 years) with a diagnosis of COPD in any setting, who had received a referral to PR (whether taken up or not); and iii) informal adult carers (≥18 years) of these patients, defined as spouse or partner, family members, friends, or significant others, who provided physical, practical, transportation, or emotional help to someone with COPD. We excluded professional carers. We also excluded studies that featured mixed participant groups where subgroups with COPD were not described or where studies were conducted in various settings and data from inpatient and outpatient services could not be separated.

Published studies were included. Conference abstracts and opinion papers were not considered for analysis. No language restrictions were applied.

Data sources and search strategy

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE and EMBASE (via OVID), CINAHL and PsycINFO (via Ebsco-Host), ASSIA and BNI (via ProQuest), Web of Science, and Cochrane Library to the end of January 2018. A search strategy was developed on MEDLINE (see Supplementary material) and adapted for other databases. The strategy included “quantitative” OR “mix* method*.” Filters for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews were adapted from Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network search filters.Citation19 We also searched “related article” searches in PubMed for all studies included in the review and scanned reference lists of all included studies and key references, searching for relevant papers citing the included papers in the Institute for Scientific Information Web of Science (Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index). An interim report of this work, searching literature up to June 2016 and without specific search criteria for quantitative and mixed methods studies, was presented at the British Thoracic Society in 2016.Citation20

Study selection and data extraction

Search results were screened on titles and abstracts and then on full text by two independent reviewers (FE and IW), gaining consensus on inclusion with input from a referee (JF) if required.

A data extraction form was piloted and two reviewers (FE and IW) independently extracted data from eligible papers. Data included study setting, sample size, recruitment method, study design, study objectives, participant/patient characteristics, methods of data collection, data analysis, recorded outcomes, limitations, and conflict of interests. We planned to tabulate data and carry out a meta-analysis using Review Manager ([RevMan], Version 5.3; The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, 2014) statistical software according to our prespecified protocol if this was appropriate.

Quality assessment

The same reviewers independently appraised study quality to assess the risk of bias in individual studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in RCTs,Citation21 the ACROBAT-NRSI (A Cochrane Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions),Citation22 and AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)Citation23 depending on the type of study.

Results

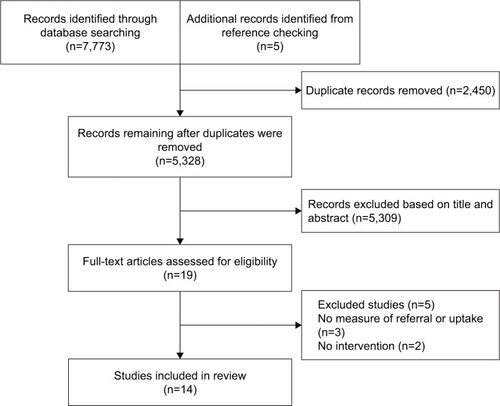

Searches identified 5,328 potentially relevant articles of which 14 met our inclusion criteria (). All were in English language. Six studies were conducted in the UK,Citation24–Citation29 four in Denmark,Citation30–Citation33 two in Australia,Citation34,Citation35 and one in USA.Citation36 One was a systematic review.Citation36 Study characteristics and findings are summarized in .

Table 1 Study characteristics

Ten studies included rates of referral to PR as an outcomeCitation24,Citation25,Citation27–Citation33,Citation36 of which eightCitation24,Citation27,Citation29–Citation33,Citation36 reported the number of patients or patient records studied, in total 44,720. This total included five large audits capturing data from 43,098 patient records (range 1,211–32,018).Citation30–Citation33,Citation36 Five studies assessed rates of uptake to PR of which three reported the number of patients studied, in total 1,426 (range 126–600).Citation26,Citation34,Citation35 One study reported only percentages.Citation25 A systematic review by Jones et alCitation37 found no eligible studies of uptake.

Populations and settings

Descriptions of patient populations were limited. Age and sex were most commonly reported and no studies reported ethnicity. Age and sex were reported by six studies that measured referralCitation24,Citation27,Citation30–Citation33 and three that measured uptake.Citation26,Citation34,Citation35 The number and/or roles of clinicians involved were reported by seven studies that measured referralCitation24,Citation25,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36 and two that measured uptake.Citation25,Citation35 Overall, patients were older (mean age ≥69 years) and 44%–64% of the samples were males.

Study designs

Study designs were heterogeneous and most were observational. Of the referral studies, two captured referral data at one time point only,Citation24,Citation25 six reported before and after longitudinal data,Citation28,Citation30–Citation33,Citation36 one reported before and after results using a historical comparison group,Citation27 and one conducted a pragmatic non-RCT.Citation29 Of the uptake studies, one captured uptake data at one time point only,Citation25 one reported before and after results using a historical comparison group,Citation26 one used a controlled before and after design,Citation34 and there was one cluster RCT.Citation35 The systematic review by Jones et alCitation37 searched for RCTs evaluating uptake and identified none.

Interventions

Most studies measured referral or uptake to PR in the context of multifaceted evidence-based management of COPD. Only one study focused specifically on referralCitation25 and one on uptake.Citation26 Interventions ranged from clinician education to system-wide change.

Studies measuring referral in primary care included a computer-guided COPD review,Citation24 educational programs for healthcare providers (HCPs),Citation30,Citation33 collaborative team-based education and empowerment,Citation36 an action research study which generated a range of interventions including education and memory aids,Citation25 general practice networks with specialist support and financial incentives,Citation28 and a patient-held scorecard comparing the patient’s own care against care quality indicators.Citation29 Secondary care interventions included education for HCPs,Citation31 education for HCPs plus a discharge bundle,Citation27 and quality monitoring through a clinical register.Citation32 Studies measuring uptake included a group opt-in session for patients prior to PR assessment,Citation26 a patient-held manual summarizing evidence on COPD treatments with questions to ask the physician,Citation34 individualized care planning supported by partnership working between general practitioners (GPs) and nurses,Citation34 and the action research study by Foster et al.Citation25

Referral was reported at the level of individual patients,Citation24 practice/department,Citation25,Citation29,Citation36 and system level or GP network.Citation28–Citation33 Uptake was reported at individual patient levels.Citation26,Citation34,Citation35

illustrates the range of characteristics of the studies. Primary care was the most common setting. Most interventions targeted clinicians. Patients were targeted in two studies measuring referralCitation27,Citation29 and three measuring uptake.Citation26,Citation34,Citation35 Two interventions were at the level of healthcare systems, both measuring referral.Citation28,Citation32 Education and learning support were the most common features of interventions that targeted clinicians.Citation25,Citation27,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36 Regarding design, three out of four studies measuring uptake had a comparison group designCitation26,Citation34,Citation35 compared to three out of 10 measuring referral.Citation27–Citation29 All studies of interventions that included elements aimed at patients had a comparison group design.Citation26,Citation27,Citation29,Citation34,Citation35

Outcomes

Referral to PR was the main outcome in eight out of 10 studies24,25,27–29,31,32,36 and uptake was the main outcome in three out of four studies.Citation25,Citation26,Citation34 There was limited detail about procedures for data collection. Most referral outcomes were measured by audits of patient records.Citation25,Citation28–Citation33,Citation36 Graves et al,Citation26 Harris et al,Citation34 and Zwar et alCitation35 measured uptake for individual patients though terms such as “enrollment”Citation34 and “attendance”Citation25 were not defined. Foster et alCitation25 asked patients about their decision to attend PR in a survey.

Conflicts of interest

Potential conflicts of interest were noted in four studies where the authors developed and owned the computer software being assessedCitation24 and where consultants from funding organizations were involved in intervention delivery and quality control.Citation30,Citation31,Citation33

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

All studies had areas of high risk of bias. In the RCT by Zwar et al,Citation35 this related to the unavoidable lack of blinding of participants (). The risk of attrition bias was unclear. Furthermore, 52 out of 234 patients allocated to the intervention group did not receive the intervention. No reasons were given for this and the risk of bias is unclear in this regard (Other bias in ). All remaining studies were considered to have a high risk of bias due to a critical risk of confounding that was associated with the study designs (). The systematic review by Jones et alCitation37 was of high methodological quality ().

Table 2 Risk of bias assessment (Cochrane RCT) for randomized studies

Table 3 Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for nonrandomized studies of interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI)

Table 4 Quality assessment of Jones et alCitation37 against the AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) measurement tool”

Study findings

Due to study heterogeneity, we considered it inappropriate to summarize results using a meta-analysis. The reported outcomes can only be understood in the context of each study and are not readily comparable across studies. Furthermore, when considering the study outcomes in light of the various characteristics shown in there were no discernible patterns to link study characteristics and outcomes.

Table 5 Summary of intervention characteristics

Referral to PR

Four studies reported statistically significant increases in PR referral. In primary care, Roberts et alCitation29 reported an increase for the intervention group following use of a patient-held quality scorecard, which was 6.1% (P=0.03) greater than that for the control group. Following a collaborative model of education and change implementation, mean referral to PR across 16 general practices increased by 5% (from 7% to 12%) (P=0.048),Citation36 and a 3.5% increase in referrals (from 16.7% to 20.2%) (P<0.01) followed an education program in primary care.Citation30 Tøttenborg et alCitation32 reported a 36% increase in referrals (from 55% to 91%) (relative risk 2.78, 95% CI, 2.65; 2.90) across hospital outpatient departments during mandatory monitoring of quality indicators.

Positive but statistically nonsignificant results followed an educational program in primary careCitation33 and an education program across outpatient departments.Citation31 Two studies reported increases based on descriptive data following use of a COPD discharge care bundle in a hospital wardCitation27 and a quality improvement intervention across primary care.Citation28 A computer-guided COPD reviewCitation24 and an action research studyCitation25 did not collect comparative data.

Uptake of PR

Two studies reported statistically significant increases in uptake. Harris et alCitation34 evaluated a patient manual summarizing evidence on COPD treatments and reported an increase of 18% in PR enrollment among participants in the most socioeconomically disadvantaged stratum compared to no increase in the matched control group (P=0.05). Zwar et alCitation35 reported a 21.5% difference in the number of intervention group patients attending PR (P=0.002) compared to controls where the intervention group had received an individualized care plan supported by partnership working between nurses and GPs.

One study did not collect comparative dataCitation25 and a statistically significant decrease in uptake followed a group opt-in patient information session compared to usual care (58.7% vs 75%, P<0.001).Citation26

Discussion

Our carefully conducted systematic review identified a heterogeneous group of studies. Most reported some positive results but only six out of 14 demonstrated statistically significant improvements. Statistically significant increases in referral followed educational sessions for clinicians in primary care,Citation30 collaborative learning sessions for HCPs,Citation36 use of a patient-held COPD care scorecard in primary care,Citation29 and continuous monitoring of care quality indicators in hospital settings.Citation32 Statistically significant increases in uptake followed use of a patient-held summary of COPD research evidence in secondary careCitation34 and a nurse/GP partnership model of care.Citation35 Significantly fewer patients who attended a group opt-in information session subsequently attended PR assessment compared to patients for whom no opt-in session was offered, although subsequent completion rates improved among those who attended.Citation26 Only three studies focused specifically on referralCitation25 or uptakeCitation26,Citation37 and we are unable to accurately evaluate the impact of a targeted approach to increase referral or uptake to PR.

The potential for generalizability from the studies is limited by four factors. Firstly, most study designs carried areas of high risk of bias. Secondly, some interventions were not well defined. For example, in two studies the terms “enrollment”Citation34 and “attendance”Citation35 were not explained and it was not possible to distinguish between attendance at pre-course assessment and the first PR class, which are separate stages in the PR pathway. Thirdly, there was limited reporting of patient and clinician populations which may be potentially nonrepresentative. Fourthly, the studies were conducted in high income countries and there were no interventions in low-to-middle income countries where over 90% of deaths globally from COPD occur.Citation2

Two of the studies performed spirometry and confirmed a COPD diagnosis in 57.8%Citation35 and 81%Citation24 of patients. Jones et alCitation37 included only participants with a diagnosis of COPD confirmed by spirometry in their systematic review and identified no studies of uptake. Evidence shows that patients on COPD registers do not always have a confirmed diagnosis with proportions varying from 73%Citation38 to 90%.Citation39 The question remains as to whether this is problematic for drawing conclusions from intervention studies. If studies do not confirm a COPD diagnosis it is possible that the COPD population is overestimated and that effect sizes are therefore over or underestimated. However, Zwar et alCitation35 provided a pragmatic argument for including patients with a clinical diagnosis of COPD that did not require confirmation by spirometry, indicating that this reflects practice in primary care, where diagnosis is often made and treatment initiated on clinical grounds.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this review are the use of recognized systematic methods and a search without language or date restriction, which reduced the risk of bias in conducting the review. A limitation is that it was not possible to verify the content of the reported PR programs to ensure that they matched the definition adopted for this review.Citation18 Due to heterogeneity among the studies and poor quality assessments relative to evidence-based medicine quality criteria it is not possible to provide clear evidence-based recommendations for practice. The scope of this review, inclusive of different study designs, provides a novel and broad insight into the extent and type of evidence in the field and can provide a useful stimulus for intervention developers and researchers.

Comparison with other studies

Our review supplements that of Jones et alCitation37 by including a broad range of study designs and not requiring spirometry-confirmed diagnosis. A Cochrane review of referral, uptake, and adherence to PR has been registered recently and will add knowledge to this field.Citation40

Whilst we cannot draw clear conclusions from our review about the efficacy of the interventions to increase referral and uptake to PR, these studies do address some of the known barriers and facilitators to referral and uptake.

Referral is impacted by accessibility of PR programs, HCPs’ knowledge of who and how to refer, the administrative burden of making a referral, successful previous referral of other patients, the influence of the referring doctor (either positive or negative), and by patients knowing what PR involves and how it will help their health.Citation41 Interventions in this review supported clinicians through education and guidance to improve their knowledge of referral and PR,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36 use of reminders and prompts,Citation24,Citation25 and the inclusion of PR referral in a discharge care bundle.Citation27 Education and learning support were the most common features of interventions directly targeting clinicians though it is unclear whether the education programs addressed the nature of the conversation between the HCP and the patient about PR referral or supported clinician skills in this regard. None of the interventions addressed accessibility of PR programs and it can only be assumed that sufficient capacity was available.

Barriers to patient uptake include transport and location,Citation42–Citation44 inconvenient timing,Citation42,Citation44 disruption to routine/other priorities,Citation41–Citation43 influence of the referring doctor,Citation42 lack of explanation of benefits,Citation44 lack of perceived benefit,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44 believing oneself to be too disabledCitation44 or that one’s conditions is not serious enough,Citation41,Citation44 negative past experience with PR or exercise,Citation44 and burden of COPD and other health conditions.Citation41 Reasons for attending include a trusted, enthusiastic doctor who explained the benefits, perceived increased severity of the condition, perceiving that PR would help increase control and independence and improve health, and perceived social benefits.Citation44 Positive reinforcement of PR by HCPs during the referral process is important.Citation41 The study by Zwar et al,Citation35 in which attendance at PR increased, provided individualized care plans and nurse support in patients’ homes, a model which could accommodate a personalized discussion over time about the benefits of PR to the patient and presumably establish a trusting relationship. However, Zwar et alCitation35 noted that although more patients in the intervention group attended PR this was still less than a third of the group. Interestingly, the information session provided in the study by Graves et al,Citation26 which informed patients about the benefits of PR, was associated with reduced attendance at assessment but did improve attendance of those who started PR. Whilst perhaps not providing motivational support for patients who were unsure about attending, it could nevertheless improve service efficiency and highlights the importance of considering the whole PR pathway. The manual of COPD evidence-based treatments provided by Harris et alCitation34 was helpful for more socioeconomically disadvantaged patients and may have facilitated a constructive clinician–patient interaction for this group. The authors also noted that more patients in this group reported actually using the manual, which would clearly influence any impact assessment. This highlights the need for good understanding of how interventions work as well as whether they work. Practical factors such as transport, travel, and timing were not addressed by the interventions.

Strategies to improve referral and uptake have also been studied in cardiac rehabilitation (CR) with some success. A systematic review of interventions to promote uptake and adherence in CR reported improvements in eight out of 10 studies of uptake but, as in our review, the authors could not make clear practice recommendations due to heterogeneity and risk of bias in the studies.Citation45 Another systematic review of interventions around referral and uptake to CR found 11 studies of referral and 13 studies of enrollment in the US, Canada, and the UK.Citation46 The highest rates of referral (up to 85%) were found in studies that implemented automatic referral orders (eg, from healthcare records or data) whereas the highest rates of enrollment (up to 86%) were achieved with a combination of automatic and liaison methods, including discussion with an HCP. Enrollment and uptake to CR can also be improved by referral and structured follow-up by nurses or therapists and early outpatient education.Citation45,Citation47,Citation48 Whether findings from CR might be translated to PR is worthy of further research. The rehabilitation pathway differs for CR because referrals typically occur at the time of hospitalization for an acute event or procedure, whereas in the UK, for example, most PR referrals occur in primary care at the time of stable disease.Citation13

Implications for practice and research

There is a call to provide recommendations to increase the delivery of PR worldwide to validate novel techniques for doing so, and to enhance evidence-based policy.Citation12 While more evidence is needed to establish the efficacy and effectiveness of different approaches, the studies reviewed here provide a useful platform for further work. The variety of interventions they represent, from one-off information sessions to system-wide improvement projects, reflects the complex nature of COPD care management and the potential value of a range of evidence building approaches.

Firstly, there is an urgent need for high quality study designs to determine the efficacy, effectiveness, and causal mechanisms of interventions. There is a lack of evidence from RCTs and we identified only one ongoing RCT to test a method not previously evaluated: a video to increase PR uptake following hospitalized exacerbations of COPD.Citation49 Whilst RCTs are the gold standard for establishing a generalizable evidence base, they may not be the only relevant evaluation design in this field. There is a need to recognize contextual factors and the diversity of PR delivery and settings across the world.Citation50 In this regard, quality improvement approaches are well suited to learn what works in a local context, particularly where rapid testing of novel interventions is needed. In contrast to research methods which aim to generate new knowledge, the aim of these approaches is to achieve positive and practical change in an identified service through focus on a well-defined problem.Citation51 These methods are accessible to service providers in “real-world” settings. Two studies reviewed here, Hull et alCitation28 and Hopkinson et al,Citation27 utilized quality improvement methods. In addition, for the researcher, realist approaches that seek to identify what works, in which circumstances, and for whom could help to recognize and accommodate contextual complexity within the evaluation design and provide more transferable learning about the impact of contextual factors.Citation52 Such methods have value in real-world settings where multiple variables cannot be controlled.

Secondly, there is a need to improve reporting of study populations as a factor to enhance external validity. Results from Harris et alCitation34 suggest differential effects across subgroups of patients and this is worthy of further investigation. None of the studies in this review reported the ethnicity of patients. In an area of East London in the UK members of some Black and minority ethnic populations have lower rates of referral to PR compared to White patientsCitation53 and there is a need to understand more about how to support PR access in ethnically diverse communities. There may also be specific issues in resource poor countriesCitation54 which are not represented among the studies in this review.

Thirdly, in their study of a group opt-in session prior to assessment, Graves et alCitation26 reported that, despite no impact on uptake, fewer intervention patients who started PR dropped out for reasons other than illness and significantly more graduated. This indicates the importance of considering the whole PR pathway. Following the patient through the entirety of their PR journey will lead to a greater understanding of how to improve service efficiency. Only two studies in this review intervened at the system levelCitation28,Citation32 and there is scope for more research in this area. More studies measured referral than uptake and more patients were included in referral studies than in uptake studies, suggesting a differential focus on these two stages.

Fourthly, interventions may benefit from theory-based design. Cox et alCitation41 used the Theoretical Domains Framework to analyze factors affecting referral and participation in PR and we have highlighted above how some of the reviewed studies addressed these factors, although it was not possible to asses this accurately without access to more detailed intervention descriptions. However, we believe that the work by Cox et alCitation41 provides a useful theoretical framework for intervention designers. Interventions could focus on specific constructs that have been shown to have relevance and then assess the impact on those constructs to generate a theoretically informed understanding of what works and why.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates the broad range of approaches aimed at increasing referral and uptake to PR across primary and secondary care. Some positive results have been demonstrated but there is limited generalizable evidence because interventions and methods are heterogeneous and descriptions of populations are limited. Further theory-based testing of promising interventions using robust methods in various populations and settings is required to draw clear conclusions about how to optimize access to PR across a range of settings.

Author contributions

JF, FE, IW, and CD conceived and designed the review. IK provided expert support and conducted the literature search. FE and IW reviewed the titles and abstracts, selected the papers, and extracted and analyzed the data. All authors were involved in drafting and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for aspects of the work. JF is the guarantor of the paper.

Acknowledgments

Delivery of this work was supported by the Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Supplementary material

MEDLINE search strategy

(((pulmonary rehabilitation.ti,ab.) or (((emphysema or copd or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chronic bronchitis or chronic asthma).ti,ab. or exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/or exp Bronchitis, Chronic/or exp Asthma/or exp Emphysema/) and ((exercis* or rehab* or physiotherap* or “physical therap*”).ti,ab. or exp Exercise Therapy/or exp Exercise/or exp rehabilitation/or exp Physical Therapy Modalities/))) and ((refer* 1 or referring or referred or referral* or assess*).ti,ab. Or exp “Referral and Consultation”/) And ((rate* or number* or audit* or percentage or barrier* or facilitat* or frequen* or infrequent* or rare* or common* or uncommon or standard* or influenc* or reluctant* or barrier* or obstacle or (meet* adj3 criter*)).ti,ab. Or exp practice patterns, physicians/or exp guideline adherence or exp data collection/))

((pulmonary rehabilitation.ti,ab.) or (((emphysema or copd or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chronic bronchitis).ti,ab. or exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/or exp Bronchitis, Chronic/or exp Emphysema/) and ((exercis* or rehab* or physiotherap* or “physical therap*”).ti,ab. or exp Exercise Therapy/or exp Exercise/or exp rehabilitation/or exp Physical Therapy Modalities/))) and ((uptake or up-take or (up adj3 take*) or non-attend* or nonattend* or attend* or engag* or (treat* adj3 refus*) or decline* or concordan* or complian* or barrier* or obstacle* or adher* or accept*).ti,ab. Or exp treatment refusal/or exp patient compliance/or exp patient acceptance of healthcare/)

or 2

((((Meta-Analysis as Topic/or Meta-Analysis/or exp Review Literature as Topic/) or ((meta analy$) or (metaanaly$) or ((systematic adj (review$1 or overview$1)))).tw. or (Cochrane or embase or psychlit or psyclit or psychinfo or psycinfo or cinahl or cinhal or (science citation index) or bids or cancerlit or reference list$ or bibliograph$ or hand-search$ or (relevant journals) or (manual search$)).ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and review/)) NOT (Comment/or Letter/or Editorial/)) Or (((Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/or randomized controlled trial/or Random Allocation/or Double Blind Method/or Single Blind Method/or clinical trial/or exp Clinical Trials as topic/or PLACEBOS/) or ((clinical trial, phase i) or (clinical trial, phase ii) or (clinical trial, phase iii) or (clinical trial, phase iv) or (controlled clinical trial) or (randomized controlled trial) or (multicenter study) or (clinical trial)).pt or ((clinical adj trial$) or ((singl$ or doubl$ or treb$ or tripl$) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)) or (placebo$) or (randomly allocated) or (allocated adj2 random$)).tw) NOT (case report.tw or letter/or historical article/))) or (quantitative or (mix* adj method*)).mp.

3 and 4

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- López-CamposJLTanWSorianoJBGlobal burden of COPDRespirology2016211142326494423

- World Health Organisation [updated 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/Accessed April 19, 2018

- British Lung FoundationChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) statistics Available from: http://statistics.blf.org.uk/copdAccessed April 19, 2018

- Medical DirectorateNHSCommissioning ToolkitCOPD2012 Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/212876/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-COPD-commissioning-toolkit.pdfAccessed September 25, 2018

- MccarthyBCaseyDDevaneDMurphyKMurphyELacasseYPulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Review)Cochrane Database Syst Rev20152CD003793

- SteinerMMcMillanVLoweDPulmonary rehabilitation: beyond breathing better. National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Audit Programme: outcomes from the clinical audit of pulmonary rehabilitation services in England 2015LondonRCP2017

- SeymourJMMooreLJolleyCJOutpatient pulmonary rehabilitation following acute exacerbations of COPDThorax201065542342820435864

- SinghSJZuwallackRLGarveyCSpruitMAAmerican Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Learn from the past and create the future: the 2013 ATS/ERS statement on pulmonary rehabilitationEur Respir J20134251169117424178930

- GriffithsTLPhillipsCJDaviesSBurrMLCampbellIACost effectiveness of an outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation programmeThorax2001561077978411562517

- BoltonCEBevan-SmithEFBlakeyJDBritish Thoracic Society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adultsThorax201368Suppl 213023229812

- SpruitMASinghSJGarveyCAn official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20131888e13e1524127811

- VogiatzisIRochesterCLSpruitMATroostersTCliniEMAmerican Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force on Policy in Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Increasing implementation and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation: key messages from the new ATS/ERS policy statementEur Respir J20164751336134127132269

- SteinerMHolzhauer-BarrieJLoweDPulmonary rehabilitation: time to breathe better. National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Audit Programme: resources and organisation of pulmonary rehabilitation services in England and Wales 2015National organisational audit reportLondonRCP2015

- JongepierLBarlowRPulmonary rehabilitation (PR) capacity, uptake and completion rate in the East of EnglandEur Respir J201648Suppl 603584

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]LondonThe Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.orgAccessed April 24, 2018

- EarlyFWellwoodIKuhnIDeatonCFuldJA systematic review of literature on interventions to increase referral to and uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation programmes in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)2016PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016043762 Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42016043762Accessed April 24, 2018

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaborationBMJ2009339b270019622552

- National Institute for Health and Clinical ExcellenceChronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and managementClinical guideline CG1012010 Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101Accessed April 24, 2018

- Strings attached: Strings attached: CADTH database search filters [Internet]OttawaCADTH2016 Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/strings-attached-cadths-database-search-filtersAccessed September 25, 2018

- EarlyFWellwoodIKuhnIP212 Interventions to increase referral to and uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation programmes for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic reviewThorax201671Suppl 3A200A201

- HigginsJPTAltmanDGGøtzschePCThe Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trialsBMJ2011343d592822008217

- SterneJACHigginsJPTReeves BC on behalf of the development group for ACROBAT-NRSIA Cochrane Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool: for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI), Version 1.0.02492014 Available from: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/population-health-sciences/centres/cresyda/barr/riskofbias/robins-i/acrobat-nrsi/Accessed September 25, 2018

- SheaBJGrimshawJMWellsGADevelopment of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviewsBMC Med Res Methodol2007711017302989

- AngusRMThompsonEBDaviesLFeasibility and impact of a computer-guided consultation on guideline-based management of COPD in general practicePrim Care Respir J201221442543023131871

- FosterFPiggottRRileyLBeechRWorking with primary care clinicians and patients to introduce strategies for increasing referrals for pulmonary rehabilitationPrim Health Care Res Dev201617322623726072909

- GravesJSandreyVGravesTSmithDLEffectiveness of a group opt-in session on uptake and graduation rates for pulmonary rehabilitationChron Respir Dis20107315916420688893

- HopkinsonNSEnglebretsenCCooleyNDesigning and implementing a COPD discharge care bundleThorax2012671909221846790

- HullSMathurRLloyd-OwenSRoundTRobsonJImproving outcomes for people with COPD by developing networks of general practices: evaluation of a quality improvement project in east LondonNPJ Prim Care Respir Med20142411408225322204

- RobertsCMGungorGParkerMCraigJMountfordJImpact of a patient-specific co-designed COPD care scorecard on COPD care quality: a quasi-experimental studyNPJ Prim Care Respir Med20152511501725811771

- LangePRasmussenFVBorgeskovHThe quality of COPD care in general practice in Denmark: the KVASIMODO studyPrim Care Respir J200716317418117516009

- LangePAndersenKKMunchEQuality of COPD care in hospital outpatient clinics in Denmark: the KOLIBRI studyRespir Med2009103111657166219520562

- TøttenborgSSThomsenRWNielsenHJohnsenSPFrausing HansenELangePImproving quality of care among COPD outpatients in Denmark 2008–2011Clin Respir J20137431932723163961

- UlrikCSHansenEFJensenMSManagement of COPD in general practice in Denmark – participating in an educational program substantially improves adherence to guidelinesInt J COPD201057379

- HarrisMSmithBJVealeAJEstermanAFrithPASelimPProviding reviews of evidence to COPD patients: controlled prospective 12-month trialChron Respir Dis20096316517319643831

- ZwarNAHermizOCominoECare of patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cluster randomised controlled trialMed J Aust2012197739439823025736

- DeprezRKinnerAMillardPBaggottLMellettJLooJLImproving quality of care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePopul Health Manag200912420921519663624

- JonesAWTaylorAGowlerHO’KellyNGhoshSBridleCSystematic review of interventions to improve patient uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPDERJ Open Res20173100089201628154821

- JonesRCMDickson-SpillmannMMatherMJCMarksDShackellBSAccuracy of diagnostic registers and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Devon primary care auditRespir Res2008916218710575

- BaxterNHolzhauer-BarrieJMcMillanVSaleem KhanMSkipperERobertsCMITime to take a breath. National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Audit Programme: clinical audit of COPD in primary care in Wales 2014–2015 National clinical audit reportLondonRCP2016

- YoungJJordanREAdabPEnocsonAJollyKInterventions to promote referral, uptake and adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (protocol)Cochrane Database Syst Rev201710CD012813

- CoxNSOliveiraCCLahhamAHollandAEPulmonary rehabilitation referral and participation are commonly influenced by environment, knowledge, and beliefs about consequences: a systematic review using the Theoretical Domains FrameworkJ Physiother2017632849328433238

- KeatingALeeAHollandAEWhat prevents people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from attending pulmonary rehabilitation? A systematic reviewChron Respir Dis201182899921596892

- MatharHFastholmPHansenIRLarsenNSWhy do patients with COPD decline rehabilitationScand J Caring Sci201630343244126426088

- SohanpalRSteedLMarsTTaylorSJCUnderstanding patient participation behaviour in studies of COPD support programmes such as pulmonary rehabilitation and self-management: a qualitative synthesis with application of theoryNPJ Prim Care Respir Med20152511505426379121

- KarmaliKNDaviesPTaylorFBeswickAMartinNEbrahimSPromoting patient uptake and adherence in cardiac rehabilitationCochrane Database Syst Rev20146CD007131

- Gravely-WitteSLeungYWNarianiREffects of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on referral and enrollment ratesNat Rev Cardiol201072879619997077

- ClarkAMKing-ShierKMDuncanAFactors influencing referral to cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs: a systematic reviewEur J Prev Cardiol201320469270023847263

- GraceSLAngevaareKLReidRDEffectiveness of inpatient and outpatient strategies in increasing referral and utilization of cardiac rehabilitation: a prospective, multi-site studyImplement Sci20127112023234558

- JonesS2015Video to increase rehabilitation uptake following hospitalised exacerbations of COPD: a randomised controlled trialISRCTN Available from: http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN13165073Accessed October 02, 2018

- SpruitMAPittaFGarveyCDifferences in content and organisational aspects of pulmonary rehabilitation programmesEur Respir J20144351326133724337043

- PortelaMCPronovostPJWoodcockTCarterPDixon-WoodsMHow to study improvement interventions: a brief overview of possible study typesBMJ Qual Saf2015245325336

- PawsonRTilleyNRealistic EvaluationLondonSage2013

- MartinABadrickEMathurRHullSEffect of ethnicity on the prevalence, severity, and management of COPD in general practiceBr J Gen Pract201262595e76e8122520773

- DesaluOOOnyedumCCAdeotiAOGuideline-based COPD management in a resource-limited setting – physicians’ understanding, adherence and barriers: a cross-sectional survey of internal and family medicine hospital-based physicians in NigeriaPrim Care Respir J2013221798523443222