Abstract

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are a mainstay of COPD treatment for patients with a history of exacerbations. Initial studies evaluating their use as monotherapy failed to show an effect on rate of pulmonary function decline in COPD, despite improvements in symptoms and reductions in exacerbations. Subsequently, ICS use in combination with long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) was shown to provide improved reductions in exacerbations, lung function, and health status. ICS-LABA combination therapy is currently recommended for patients with a history of exacerbations despite treatment with long-acting bronchodilators alone. The presence of eosinophilic bronchial inflammation, detected by high blood eosinophil levels or a history of asthma or asthma–COPD overlap, may define a population of patients in whom ICSs may be of particular benefit. Prospective clinical studies to determine an appropriate threshold of eosinophil levels for predicting the beneficial effects of ICSs are needed. Further study is also required in COPD patients who continue to smoke to assess the impact of cell- and tissue-specific changes on ICS responsiveness. The safety profile of ICSs in COPD patients is confounded by comorbidities, age, and prior use of systemic corticosteroids. The risk of pneumonia in patients with COPD is increased, particularly with more advanced age and worse disease severity. ICS-containing therapy also has been shown to increase pneumonia risk; however, differences in study design and the definition of pneumonia events have led to substantial variability in risk estimates, and some data indicate that pneumonia risk may differ by the specific ICS used. In summary, treatment with ICSs has a role in dual and triple therapy for COPD to reduce exacerbations and improve symptoms. Careful assessment of COPD phenotypes related to risk factors, triggers, and comorbidities may assist in individualizing treatment while maximizing the benefit-to-risk ratio of ICS-containing COPD treatment.

Plain-language summary

Increasing treatment options for COPD add to the complexity of treatment and require review of clinical data to inform treatment decisions. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in combination with long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) reduce the risk of exacerbations and improve lung function and health status in patients with COPD compared with ICS or LABA therapy alone. Certain patients may particularly benefit from ICS therapy, including those with frequent exacerbations despite long-acting bronchodilator therapy and those with evidence of eosinophilic bronchial inflammation, which can be determined by high levels of blood eosinophils and/or a history of asthma or asthma–COPD overlap. Although relatively uncommon, an increased risk of pneumonia is associated with ICS use and appears to be dependent on the specific ICS used. Recent studies of triple therapy combining an ICS, LABA, and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist demonstrated significant benefits compared with dual therapy and support their widespread use in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations, but longer-term data and comparisons of specific triple-therapy regimens are needed to optimize therapy.

History of inhaled corticosteroid use in COPD

COPD is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and progressive airflow limitation.Citation1 Goals of COPD management are to minimize the impact of symptoms, improve levels of physical activity, and decrease the future risk of exacerbations responsible for disease progression.Citation1 Achieving these goals is challenging due to the heterogeneous nature of COPD and an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease. Inflammatory changes have been observed in the lungs as a result of inhaling cigarette smoke, as well as noxious particles and gases from other sources.Citation1 The presence of increased numbers of inflammatory cells in airway biopsies and bronchoalveolar lavage, including neutrophils, alveolar macrophages, and T lymphocytes, in the lungs of smokers susceptible to the development of COPD may act directly on airway and alveolar tissue, promoting airway narrowing and airflow limitation.Citation2,Citation3 These data, in conjunction with the effectiveness of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in the treatment of asthma, encouraged routine use of ICSs in patients with COPD. Over the past three decades, extensive research has been conducted evaluating the use of ICSs in such patients. This article reviews the history of the use of ICSs in COPD, with a focus on pivotal clinical studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. The effect of smoking on ICS response in COPD is also discussed, and safety considerations for ICS use in COPD are examined, particularly regarding long-term safety and pneumonia risk. The applicability of these data is considered in light of current treatment practices, as well as their relevance to future therapy for COPD, including triple-therapy regimens.

Use of ICS monotherapy in COPD

In the 1990s, short-term studies of ICS monotherapy in patients with COPD and chronic bronchitis found that anti-inflammatory therapy reduced bronchial inflammation, but had varying effect on lung-function measures of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and peak expiratory flow (PEF).Citation4–Citation6 In a 6-month study, fewer exacerbations, particularly the most severe exacerbations, occurred in patients treated with ICSs compared with placebo.Citation6 Subsequently, four long-term (3-year) randomized, placebo-controlled studies of ICS in patients with COPD were conducted to determine the effect of therapy on the rate of decline in pulmonary function, the results of which are discussed further herein.Citation7–Citation10 These studies identified varying effects of ICSs on outcomes of interest in COPD, but failed to show benefit of ICS monotherapy on pulmonary function (). A meta-analysis of ICS studies investigating lung function in patients with COPD showed that ICS use did not slow the rate of FEV1 decline in 3,571 patients over 24–54 months.Citation11 In addition, a subsequent pooled analysis of 3,911 patients showed that after 6 months, ICS therapy did not modify FEV1 decline in patients with moderate-severe COPD.Citation12

Table 1 Long-term studies of ICSs as monotherapy for patients with COPD

Lung Health Study II

Participants from the Lung Health Study smoking-cessation trial were recruited for a second study to assess the effect of triamcinolone acetonide in delaying decline in lung function in participants with COPD.Citation7 A total of 1,116 smokers (or those who had quit smoking within the prior 2 years) with airflow obstruction, defined as an FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio <0.70 and FEV1 30%–90% predicted, were enrolled. Although asthma diagnosis was not technically an exclusion criterion, patients who used bronchodilators or ICSs regularly were excluded, effectively excluding those with symptomatic asthma. The primary outcome measure, rate of decline in postbronchodilator FEV1, showed no significant effect of ICS treatment vs placebo (44.2 vs 47.0 mL per year, respectively). Most respiratory symptoms, including cough, phlegm, wheezing, and breathlessness, over the preceding year did not differ significantly between treatment groups at 36 months. Fewer new or worsening respiratory symptoms were found in the ICS group. The rate of unscheduled physicians’ visits and hospitalization for respiratory conditions was lower in the ICS group, but visits to the emergency department (for respiratory and nonrespiratory conditions) and all health-care visits (for nonrespiratory conditions) were similar between treatment groups. At baseline, airway reactivity was similar between groups. At 9 and 33 months, the ICS group had significantly less reactivity to methacholine challenge than placebo (P=0.02). Overall, health-related quality of life (measured by the SF36) showed no changes associated with treatment, except for a slightly worse mental health subscale score at 36 months in the ICS group compared with placebo.

European Respiratory Society study on COPD

Across nine European countries, 1,277 smokers aged 30–65 years with postbronchodilator FEV1 50%–100% predicted and prebronchodilator FEV1:slow vital capacity ratio <70% were randomized to receive budesonide dry-powder inhaler or placebo for 3 years.Citation8 Patients with a history of asthma were excluded. Changes in postbronchodilator FEV1 over the first 6 months were significantly different between ICSs (improved at a rate of 17 mL/year) and placebo (declined by a rate of 81 mL/year, P<0.001); however, by 9 months the slopes of FEV1 decline were similar between treatment groups (P=0.39). Among those who completed the 3-year study (n=912), the median decline in FEV1 over 3 years was 140 mL in the ICS group and 180 mL in the placebo group (P=0.05). ICS use was more effective in patients who smoked less, but there was no association of the slope of FEV1 decline with age, sex, baseline FEV1, presence/absence of serum IgE antibodies, or reversibility of airflow limitation.

Copenhagen City Lung Study

Participants in the Copenhagen City Heart Study were eligible for the lung study if they were aged 30–70 years, had an FEV1:FVC ratio ≤0.7, and had no self-reported asthma.Citation9 Smoking history was not an inclusion criterion, and long-term CS treatment (more than two episodes of >4 weeks duration) was the main exclusion criterion. A total of 290 patients were randomized to budesonide or placebo. There was no significant effect of ICSs on rate of FEV1 decline, and stratification by sex, smoking status, and baseline FEV1 did not affect these results. No significant differences were observed between treatment groups for occurrence of symptoms, exacerbations, or reversibility to β2-agonist treatment.

Inhaled Steroids in Obstructive Lung Disease in Europe (ISOLDE) study

Current or former smokers aged 40–75 years with non-asthmatic COPD, FEV1:FVC ratio <70%, baseline post-bronchodilator FEV1 ≥0.8 L but <85% predicted were eligible for the ISOLDE study.Citation10 A total of 751 patients were randomized to fluticasone propionate or placebo. No significant difference in annual rate of FEV1 decline was observed between ICSs and placebo (50 vs 59 mL/year, P=0.16), and slopes of decline were not influenced by smoking status, age, sex, or FEV1 response to oral CSs. The predicted mean FEV1 at 3 and 36 months was significantly higher with ICSs by 76 and 100 mL, respectively, vs placebo (P<0.001). The median yearly exacerbation rate was 25% lower for ICS vs placebo (0.99 vs 1.32 per year, P=0.026). In both treatment groups, health status measured by the disease-specific St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) improved after the first 6 months of treatment (slight decrease in SGRQ total score), but thereafter it worsened (increase in SGRQ score), and the rate of worsening was slower with ICSs than placebo (increase of 2.0 vs 3.2 units/year, respectively, P=0.004).

The results of these four studies consistently showed that ICS monotherapy did not reduce the accelerated rate of decline in pulmonary function that is characteristic of COPD, and thus ICS monotherapy is not disease-modifying. The only therapy proven to slow FEV1 decline in COPD is smoking cessation.Citation13 However, ICSs improved some key secondary outcomes, including COPD symptoms, health-care utilization, airway reactivity, and notably the frequency of exacerbations. Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials with at least 6 months of follow-up comparing ICS monotherapy vs placebo found a statistically significant reduction (18%–24%) in risk of exacerbations with ICSs.Citation14,Citation15 Moreover, when the reduction in exacerbation risk by ICSs was regressed against initial FEV1 percentage predicted, it was found that the more severe the airflow obstruction, the greater the risk reduction.Citation14 In addition, ICS therapy was also shown to decelerate the rate of worsening of health status measured by the SGRQ, with a 1.4-unit improvement (decrease in SGRQ score) relative to placebo.Citation14 A Cochrane database review of randomized controlled trials comparing ICSs and placebo also showed the effect of ICSs on reducing exacerbations and slowing the rate of decline in health-related quality of life.Citation16 The ICS effect was not predicted by oral CS response, bronchodilator reversibility, or bronchial hyperresponsiveness.

The net impact of these studies in today’s world of combination therapy for COPD is that effects of CSs, at least when administered alone, are often slow to develop, and responses in the first 6 months of therapy may not remain the same in the long term. Far fewer studies have been done on the effect of CS withdrawal in COPD, and few current combination-therapy studies require a 6-month washout prior to initiation of the trial.

Barnes et al reviewed cellular and molecular mechanisms of COPD pathogenesis and proposed several factors that may explain the limited response to ICS monotherapy in this disease.Citation17,Citation18 ICSs or oral CSs do not suppress inflammation in COPD, even at high dosages. In COPD, the numbers of airway neutrophils are increased, but they are not fully suppressed by CSs. In addition, resistance to CSs may be related to decreased activity and expression of HDAC2 in inflammatory cells of patients with COPD as a result of increased oxidative and nitrative stress from cigarette smoking. ICSs may have a small bronchodilator effect that is not disease-modifying, but additional investigation is warranted. The lack of significant efficacy on the rate of decline of FEV1 may have prevented exploration of the dose response for ICSs in COPD.Citation1 In 2014, a randomized, prospective study compared two dosages of fluticasone (500 and 1,000 µg/day) in patients with COPD and an FEV1:FVC ratio <70%, FEV1 <80% predicted, and smoking history >10 pack-years.Citation19 The higher dosage was associated with improved lung function and symptoms, decreased exacerbations, and better quality of life compared to the lower dosage. In asthma, there is a tendency to administer higher dosages of ICS than needed for symptom control; however, this may increase the risk of adverse events, such as adrenal suppression, osteoporosis, and growth inhibition in children.Citation20,Citation21 Therefore, for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory approval, efficacy differences between dosage groups must be demonstrated for COPD.Citation22

Use of ICSs in combination with LABAs

Combining drugs with different modes of action may improve outcomes. Two-way synergistic activity between ICSs and LABAs has been demonstrated.Citation23,Citation24 One of the cellular actions of ICSs is to translocate glucocorticoid receptors from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.Citation24 This action is enhanced in the presence of β-agonists and causes an anti-inflammatory effect greater than either drug alone, without the need to increase the ICS dosage.Citation23 In addition, ICSs activate β-receptor genes to produce more β-receptors, thereby enhancing the bronchodilator effect of LABAs.Citation25 Numerous clinical studies have been conducted evaluating ICS-LABA combinations in patients with COPD, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses have pooled their results to inform treatment decisions. Relevant studies are discussed in the following paragraphs.

The Towards a Revolution in COPD Health (TORCH) trial was a pivotal, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study comparing salmeterol plus fluticasone propionate (50 and 500 µg, respectively, taken twice daily) with each component alone and placebo over 3 years.Citation26 Patients with COPD were enrolled if they had at least a 10-pack-year smoking history, FEV1 <60% predicted, and an FEV1:FVC ratio ≤0.70.Citation26 Among 6,184 randomized patients, the risk of death was reduced by 17.5% with the ICS-LABA combination vs placebo (P=0.052). ICS-LABA significantly reduced the rate of exacerbations by 25% compared with placebo (P<0.001) and improved health status and FEV1 compared with either component alone or placebo. A subsequent double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study included patients aged ≥40 years with COPD who had at least a 10-pack-year smoking history, FEV1:FVC ratio ≤0.70, FEV1 ≤50% predicted, and at least one exacerbation in the past year requiring oral CSs, antibiotics, or hospitalization.Citation27 Among 782 randomized patients, a 30.5% reduction in mean annual rate of moderate-severe exacerbations was observed with salmeterol plus fluticasone propionate (50 and 250 µg, respectively) compared with salmeterol alone (P<0.001) at half the dose of fluticasone propionate used in the TORCH study.

In a 2003 review of three ICS-LABA combination-therapy studies in COPD patients, a 30% reduction in exacerbations was observed vs placebo and trough FEV1 improved vs placebo (101 mL/year, 95% CI 76–126) or either therapeutic agent alone (ICS 50 mL/year, 95% CI 26–74; LABA 34 mL/year, 95% CI 11–57).Citation14 In two Cochrane database systematic reviews, ICS-LABA combination therapy administered in a single inhaler was compared to LABA or ICS monotherapy.Citation28,Citation29 Across nine eligible studies comparing ICS-LABA to LABA alone, the exacerbation rate was reduced by 24% (95% CI 0.68–0.84) with combination therapy, but there was no difference in mortality (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76–1.11).Citation28

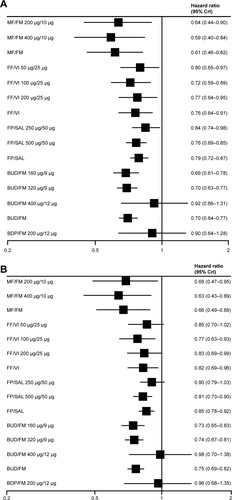

In six studies that compared ICS-LABA vs ICS monotherapy, a significant 13% reduction in the rate of exacerbations was noted (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.80–0.94) and the odds of death were significantly lower with combination therapy (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.64–0.94).Citation29 In addition, a 2014 Bayesian network meta-analysis evaluated randomized controlled trials of at least 12 weeks duration comparing fixed-dose ICS-LABA combinations with active control or placebo, and found that ICS-LABA reduced moderate-severe exacerbations, with the exception of beclomethasone dipropionate–formoterol, which had the lowest sample size of all groups ().Citation30 HRs ranged from 0.59–0.92 for ICS-LABA vs placebo and 0.63–0.98 for ICS-LABA vs LABA monotherapy. Medium-and high-dose ICS-LABA combinations were similarly effective in reducing the rate of moderate-severe exacerbations.

Figure 1 Effectiveness of ICS-LABA inhalers.

Abbreviations: BDP, beclomethasone dipropionate; BUD, budesonide; CrI, credibility interval; FF, fluticasone furoate; FM, formoterol; FP, fluticasone propionate; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; MF, mometasone furoate; SAL, salmeterol; VI, vilanterol.

Estimates of treatment effect across these systematic reviews may have differed as a result of clinical trial heterogeneity, particularly with regard to baseline exacerbation history and lung function and how a COPD exacerbation was defined within a study.Citation29,Citation31 Despite these differences, a clear effect of ICS-LABA combination therapy on exacerbations was demonstrated, and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2018 report concluded that ICS-LABA combination therapy was more effective than either agent alone in reducing exacerbations, as well as improving lung function and health status.Citation1

Recent post hoc analyses of published trials have examined the early response to ICS-LABA combination therapy.Citation32,Citation33 Lower exacerbation rates and improved lung function (FEV1 and PEF) were evident as early as 3 months after starting treatment with budesonide–formoterol vs placebo. Early improvements in FEV1 and total score on the SGRQ were associated with future response, and early FEV1 improvements (but not SGRQ-score improvements) predicted lower risk of future COPD exacerbations.

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), such as tiotropium, have a prolonged bronchodilator effect that has been shown to reduce exacerbations to a greater degree than LABA monotherapy.Citation1,Citation34,Citation35 Despite being the most commonly prescribed first-line treatments, few clinical studies have compared LAMA monotherapy to ICS-LABA combination therapy.Citation36 Using a large administrative claims database in the US, the real-world effectiveness of tiotropium was compared to budesonide–formoterol. The ICS-LABA combination reduced the risk of COPD exacerbation by 22% compared with LAMA monotherapy; however, the results could have been skewed by a high number of patients having possible comorbid asthma. The Investigating New Standards for Prophylaxis in Reducing Exacerbations (INSPIRE) study compared the efficacy of salmeterol–fluticasone with tiotropium monotherapy in preventing exacerbations in patients with severe and very severe COPD.Citation37 The exacerbation rate was not significantly different between the groups treated with ICS-LABA therapy and LAMA monotherapy, but the ICS-LABA group had better health status and was less likely to withdraw. The fact that LABAs and LAMAs work on different receptors to induce bronchodilation provides a rationale for their use in combination to optimize bronchodilation.Citation38 The comparative efficacy of LAMA-LABA (dual bronchodilators) vs ICS-LABA therapy in reducing exacerbations is currently a matter of keen interest. The Effect of Indacaterol Glycopyrronium vs Fluticasone Salmeterol on COPD Exacerbations (FLAME) study compared the efficacy of a LAMA-LABA combination (glycopyrronium 50 µg–indacaterol 110 µg) with ICS-LABA (fluticasone 500 µg–salmeterol 50 µg) therapy in reducing exacerbation risk for patients with COPD.Citation39 For patients with a history of exacerbation in the previous year, the annual rate of moderate or severe exacerbation was significantly lower for the LAMA-LABA group (0.98) than for the ICS-LABA group (1.19, P<0.001).

Predictors of response

Post hoc analyses suggest eosinophil counts in blood and sputum may be used as predictive biomarkers for the efficacy of ICSs in reducing exacerbations.Citation40–Citation43 Dose–response effectiveness of ICSs has been demonstrated in patients with elevated eosinophils,Citation44 and eosinophil levels may be able to direct treatment during COPD exacerbations. Eosinophilic inflammation in COPD, defined as sputum eosinophils ≥3%, has been reported in up to 28% of cases during an acute exacerbation and up to 38% of patients with stable disease.Citation44 However, measurement of sputum eosinophils is unsuitable for point-of-care testing and requires experience to differentiate inflammatory cell counts. Measurement of blood eosinophils may be a more useful biomarker for routine practice. The threshold for eosinophilic inflammation continues to be debated, with some reports suggesting a threshold of >2%, 3%, or 4% of the total white-blood-cell count, whereas others propose a total eosinophil count of 150, 220, or 300 cells/µL.Citation45,Citation46

The INCONTROL study showed that for patients with blood-eosinophil counts ≥100 cells/µL, exacerbations were reduced significantly more with budesonide–formoterol compared with formoterol alone (P=0.015).Citation42 The higher the blood-eosinophil count, the greater the exacerbation rate without ICSs and the greater the reduction in exacerbations with ICSs, which tends to reach a plateau around eosinophil counts of 400 cells/µL. The impact of blood-eosinophil count on response to ICSs was also found to be greater as the eosinophil count increased by Pascoe et al in their analysis of data from two parallel randomized controlled trials on the addition of fluticasone furoate to vilanterol.Citation47

Disparate findings for blood eosinophils were reported in the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD (SPIROMICS) cohort, in which blood eosinophils alone were not a reliable predictor of COPD exacerbations in contrast to sputum eosinophils, and the association between blood and sputum eosinophils was weak.Citation48 Differences in study populations could account for the disparate findings, as the INCONTROL study had a larger number of smokers with more exacerbations compared with the SPIROMICS cohort.Citation42,Citation48

Elevated eosinophil counts in the blood and airway walls are also observed in patients with COPD who have other signs of inflammation.Citation49 Tamada et al evaluated 331 COPD patients for asthma-like airway inflammation or atopic factors using fractional exhaled nitric oxide and serum IgE, respectively.Citation50 High fractional exhaled nitric oxide (≥35 parts per billion) was present in 16% of patients, high IgE (≥173 IU/mL) occurred in 36% of patients, and both factors were present in 8% of patients. Furthermore, there is another type of COPD that occurs with asthma, termed asthma–COPD overlap (ACO). A clear definition of ACO has yet to be determined,Citation50,Citation51 but a systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 studies including COPD and asthma used a definition of any COPD patient with at least one of the following asthma characteristics: diagnosis of asthma, FEV1 reversibility ≥12% and ≥200 mL of change from baseline, PEF variability ≥20%, and airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine or histamine.Citation51 Across the 17 studies, the pooled prevalence of ACO was 27% and 28% in population- and hospital-based studies, respectively. In five studies, ACO was associated with worse outcomes, including more frequent exacerbations, hospitalizations, and emergency-department visits, and two studies reported significantly higher use of ICS-LABA combinations in patients with ACO than those with COPD. Objective measures of airway inflammation and/or atopy (eg, IgE levels) indicate a smaller proportion of patients with ACO defined by symptoms, lung function, or physician diagnosis; however, these measures may be important for identifying patients who would benefit from ICS-LABA therapy.Citation1 The presence of eosinophilic inflammation has not been studied extensively in this population.

Effect of smoking status on ICS response

Despite a causal link between cigarette smoking and COPD, a substantial percentage of patients with moderate-severe COPD continue to smoke (30%–43%).Citation52 Sustained smoking cessation reduces the rate of decline in FEV1 and decreases respiratory symptoms among smokers with early COPD.Citation53 However, reductions in the amount of smoking up to 50% have no observable effect on the decline in FEV1, suggesting that total or near-total abstinence from smoking is required to reduce the effect of cigarette smoke on lung function.Citation53

The adverse effects of smoking in patients with COPD or asthma have been attributed to increased airway inflammation and reduced CS responsiveness,Citation54 but the majority of studies examining the effect of smoking on CS responsiveness have been conducted in patients with asthma.Citation55 Although it has been proposed that the oxidative and nitrative stress associated with cigarette smoking may inactivate HDAC2 in COPD patients and contribute to ICS resistance,Citation17 studies of smokers and ex-smokers generally have failed to identify a significant difference of ICSs on clinical and inflammatory parameters, including HDAC2.Citation55,Citation56 Reductions in bronchial mast cells have been observed with both short- and long-term ICS treatment in smokers and ex-smokers with COPD, whereas reductions in CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells were observed with short-term ICSs in current smokers only.Citation55 These differential effects of ICSs on specific cell types may be related to epigenetic regulation occurring with DNA methylation and histone modification.Citation55 In a comparison of ICS therapy in smokers and ex-smokers with COPD, IL8 and neutrophil-related elastase activity increased in smokers and were unchanged or decreased in ex-smokers.Citation57 Sputum eosinophils may be reduced in smokers as a result of the nitric oxide and carbon monoxide present in cigarette smoke.Citation54 A recent post hoc analysis of budesonide–formoterol studies in patients with COPD (INCONTROL) found that among current smokers, a greater reduction in exacerbation rate was observed with ICS-LABA therapy vs LABA alone at higher peripheral blood-eosinophil counts.Citation42 These cell- and tissue-specific responses may be related to the heterogeneous nature of COPD, and suggest that reduced steroid responsiveness is not a general characteristic of the disease.Citation42,Citation55 These findings highlight the need for further evaluation of appropriate biomarkers of disease severity and treatment selection and their relationship to smoking status.

Safety considerations

A review of long-term studies of ICS monotherapy in patients with COPD revealed important information about their safety (). Skin bruising and oral candidiasis were increased with ICS therapy in most studies.Citation7,Citation8,Citation10,Citation43,Citation58 In a subset of patients from the Lung Health Study, no effect of ICSs on adrenal function was observed over the 3-year study duration.Citation59 These pivotal long-term studies of ICS mono-therapy in COPD patients did not identify a difference in occurrence of cataracts compared with placebo.Citation7,Citation8,Citation10 However, an increased risk of cataracts was observed in a population-based, cross-sectional study of more than 3,000 patients, in which ICS use was associated with significantly increased prevalence of nuclear and posterior subcapsular cataracts, and higher cumulative lifetime doses were associated with higher risks.Citation60 In a follow-up analysis 10 years later, the risk of incident cataracts was significant only for patients who had ever used both ICSs and oral CSs.Citation61 Moreover, using a large electronic medical record database in the UK, ICSs or ICS-LABA (fluticasone propionate–salmeterol) combination therapy was not associated with increased risks of cataracts or glaucoma.Citation62 The 1-year Efficacy and Tolerability of Budes-onide/Formoterol in One Hydrofluoroalkane Pressurized Metered-Dose Inhaler in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (SUN) study of budesonide–formoterol in COPD patients identified numerically more frequent adverse events typically associated with ICSs, including oral candidiasis, ocular effects, skin effects, and bone effects, in the ICS-LABA group than the LABA-alone or placebo groups.Citation63 However, there were no differences in objectively measured changes in lenticular opacity or intraocular pressure, nor clinically relevant changes in bone-mineral density (BMD), across the three treatment groups.

Osteoporosis is a systemic feature of COPD, with prevalence that is two to five times higher than that in age-matched subjects without airflow obstruction.Citation64 In a cross-sectional study of COPD patients, the dosage or duration of ICSs or oral CSs used was not different between those with osteoporosis and those with normal bone mass.Citation64 Over the 3-year TORCH study, changes in BMD at the hip and lumbar spine were small, and there were no significant differences between any of the active treatment groups (ICS-LABA, ICS alone, LABA alone) and placebo.Citation65 Long-term studies analyzed in the Cochrane database review did not show any major effect of ICS therapy on fractures or BMD over 3 years.Citation16 In contrast, a meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials (of which 14 evaluated fluticasone and two budesonide) showed an increased risk of fractures (>20%) with more than 24 weeks of ICS therapy vs control.Citation66 Significant reduction in BMD at the lumbar spine (1.33%, P=0.007) and femoral neck (1.78%, P<0.001) was observed with triamcinolone in the Lung Health Study,Citation7,Citation67 but not with budesonide in the European Respiratory Society study (a small but significant decline in femoral trochanter BMD was observed with placebo vs budesonide, P=0.02).Citation8 Current recommendations suggest measuring BMD in patients with COPD intermittently to assess fracture risk and treating those with significantly reduced BMD.Citation68

Effect of ICSs on pneumonia risk in patients with COPD

The risk of pneumonia is increased in patients with COPD and further increased in those with a history of exacerbations and more severe disease.Citation69,Citation70 ICS-containing therapy for COPD has generally been associated with an increased risk of nonfatal pneumonia.Citation70 A 2009 meta-analysis of 18 studies of ICS therapy in COPD estimated an approximately 60% increased risk of pneumonia without a significant increase in pneumonia-related death or overall mortality.Citation71 In a new-user cohort study using a medical record database, ICS use was associated with a 49% increased risk of pneumonia (vs long-acting bronchodilator) that was attenuated to 19% with at least 6 months of exposure.Citation70

Differences in study design and duration, population studied, and definition of pneumonia events may contribute to variability in pneumonia rates across studies.Citation69,Citation70 Pneumonia risk may also differ by the specific ICS used. In the 2009 meta-analysis, two of 18 trials evaluated budesonide at 800 µg/day, and 16 of 18 trials evaluated fluticasone propionate at dosages of 1,000 µg/day (N=10) or 250 µg/day (N=6). In a separate meta-analysis of seven large budesonide studies in COPD, no significant increased risk of pneumonia was determined with budesonide vs control of either placebo or formoterol (overall risk 1.05, 95% CI 0.81–1.37).Citation72 The Investigation of the Past 10 Years Health Care for Primary Care Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (PATHOS) study investigated the incidence of pneumonia in patients with COPD using data from national Swedish health registries, comparing propensity-matched populations treated with budesonide–formoterol (N=2,734) and fluticasone–salmeterol (N=2,734).Citation73 Patients in the fluticasone–salmeterol group experienced an approximately 75% greater occurrence of pneumonia, including pneumonia requiring hospitalization, compared with the budesonide–formoterol group (P<0.001). Additionally, among patients using ICSs at baseline and followed for 4 years in the Understanding Potential Long-Term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium (UPLIFT) study, the risk of pneumonia was increased by >20% compared with those who did not use ICSs, but this increased risk was noted only in patients receiving fluticasone propionate and not in those using other ICSs ().Citation74 Fluticasone was also associated with a higher risk of any pneumonia, but not serious pneumonia, compared with budesonide in a Cochrane database review of 43 randomized controlled trials (26 fluticasone studies and 17 budesonide studies).Citation75 Differences in outcome between ICSs and placebo may be due to uneven distribution of baseline characteristics because patients with more severe disease received more intensive treatment; however, patient subgroups based on the ICS they received were well matched, such that baseline characteristics cannot explain differences between fluticasone and other ICSs.Citation74 Fluticasone differs structurally from beclomethasone and budesonide because it has a fluorine moiety, which leads to distribution in the lipid membranes and slower clearance from lungs and other tissue, which may impact lung immunity and inflammatory responses.Citation74,Citation76 This study also suggested that the use of LAMA therapy may ameliorate some of the respiratory adverse effects of ICSs, supporting their use in combination.Citation74 The absolute risk of pneumonia is low,Citation77 and the authors’ experience suggests that few physicians or patients avoid ICS therapy as a result of this risk. In summary, the physician and patient must consider the benefit of ICSs in reducing the future risk of exacerbations in relation to the increased pneumonia risk of ICS-containing therapy.Citation70,Citation72

Table 2 Distribution of pneumonia events and incidence rates by treatment in the UPLIFT study

Role of ICSs in current COPD treatment

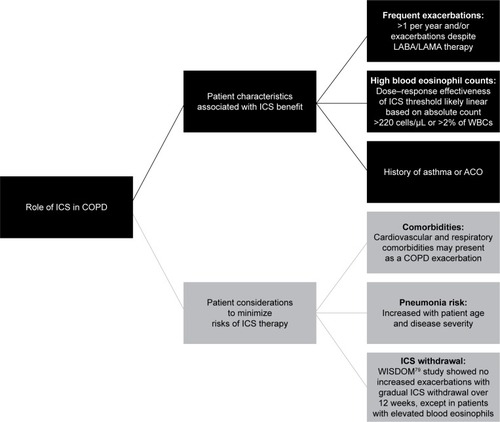

Large clinical trials and systematic reviews/meta-analyses of clinical trial data provide evidence for the development of COPD-treatment guidelines.Citation1 Currently, GOLD guidelines provide recommendations for drug selection based on a patient’s symptom intensity and disease severity assessed by prior and future risk of exacerbations.Citation1,Citation45 ICS-LABA combinations have been shown to reduce exacerbations, improve lung function, and improve health status.Citation14,Citation26,Citation28–Citation30 ICS-LABA combinations are thus recommended as a treatment option for COPD patients with a history of frequent exacerbations,Citation1 but they are commonly prescribed as first-line treatments, regardless of COPD severity.Citation38,Citation74 Over the past 5 years, there has been an increase in new drugs and delivery devices, adding to the complexity of COPD treatment options.Citation45 However, the data reviewed herein provide information to identify patient groups that may benefit from ICS use (). Concerns with ICS use are related to the safety considerations described in the previous section and the potential risks associated with withdrawal of ICS therapy.Citation45,Citation74,Citation78 Long-term adverse events described in some studies are complicated by concomitant oral CS use and confounding disease severity, as well as comorbidities. It is important that exacerbations be differentiated from other events that may be related to common comorbidities of COPD, including acute coronary syndrome, worsening congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia.Citation1 Although for many years it was believed that stopping ICS use could trigger an exacerbation, it has recently been shown that withdrawal of ICSs is possible, particularly when other medications are introduced concomitantly.Citation45 In the Withdrawal of Inhaled Steroids during Optimized Bronchodilator Management (WISDOM) study, ICS therapy was withdrawn gradually over 12 weeks from a triple combination, without an overall increased risk of exacerbations compared with the group that remained on triple therapy (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.94–1.19).Citation79 However, in the group in which ICS therapy was withdrawn, FEV1 declined and health status tended to worsen significantly, albeit modestly, compared with patients who remained on ICS therapy. Moreover, in a subset of the overall patient population (~20%) with eosinophil counts ≥4% or ≥300 cells/µL, withdrawal of ICSs was associated with an increased risk of exacerbations.Citation46 Still, for patients who are at low risk of exacerbation (ie, FEV1 >50% predicted, fewer than two exacerbations/year), ICSs can be withdrawn safely as long as maintenance LABA therapy is continued.Citation80

Figure 2 The role of ICS in patients with COPD.

Abbreviations: ACO, asthma–COPD overlap; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; WBCs, white blood cells.

Future directions: triple therapy and beyond

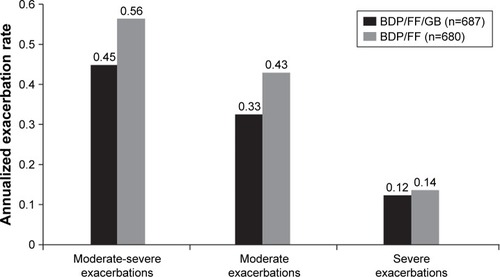

The step up to triple therapy with ICS + LABA + LAMA may improve lung function and patient-reported outcomes for COPD patients (eg, the addition of LAMA to ICS-LABA reduces exacerbation risk).Citation1 In the Single Inhaler Triple Therapy vs Inhaled Corticosteroid Plus Long-acting β2-Agonist Therapy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (TRILOGY) study of COPD patients with severe or very severe airflow limitation (ie, FEV1 <50% predicted and at least one moderate or severe exacerbation in the previous 12 months), triple therapy (beclomethasone dipropionate–formoterol fumarate–glycopyrronium bromide) in a single inhaler significantly improved predose and postdose FEV1 and SGRQ total score and also reduced the exacerbation rate by 23% compared with beclomethasone dipropionate–formoterol fumarate ().Citation81 Patients enrolled in this study could have been receiving ICS-LABA, ICS-LAMA, or LABA-LAMA combination therapy or LAMA monotherapy and entered a 2-week run-in phase in which they received ICS-LABA prior to randomization. As such, escalation from LABA-LAMA therapy directly to triple therapy needs to be evaluated. The recently published Lung Function and Quality of Life Assessment in COPD with Closed Triple Therapy (FULFIL) study results support a benefit of single-inhaler triple therapy compared with ICS-LABA for lung function, health status, and exacerbation rate at 24 weeks.Citation82 Moreover, results of the Informing the Pathway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) study demonstrated that the triple combination of fluticasone furoate–umeclidinium–vilanterol reduced the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations more effectively than both the ICS-LABA (fluticasone furoate–vilanterol, 15% difference, P<0.001) and the LABA-LAMA (umeclidinium–vilanterol, 25% difference, P<0.001) combinations.Citation83 Interestingly, these results imply that ICS-LABA might be superior to LABA-LAMA in reducing exacerbations in this >10,000-patient study, in direct contrast to the findings from the FLAME study.Citation39 A number of factors may have contributed to the disparate findings in the IMPACT and FLAME studies, including different patient populations, study-design differences for the run-in period and ICS withdrawal, and different methods of statistical analyses of end points. More data are needed to determine appropriate patient selection criteria for ICS-LABA, LABA-LAMA, and triple-therapy regimens.

Figure 3 COPD exacerbations in the TRILOGY study.

Abbreviations: BDP, beclomethasone dipropionate; FF, fluticasone furoate; GB, glycopyrronium bromide.

In contrast to these positive results for triple therapy, a 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of seven trials of triple therapy using tiotropium and an ICS-LABA fixed-dose combination in a separate inhaler vs tiotropium monotherapy showed no significant benefit for triple therapy on mortality or exacerbations.Citation84 Improvement in FEV1 and SGRQ score was greater with triple therapy, but lower than the minimal clinically important difference. Six of the seven trials were ≤24 weeks in duration. These findings highlight potential differences in triple-therapy regimens, the need for studies of longer duration, and the impact of single inhalers (presumably as a result of increased adherence) compared with multiple inhalers. Indeed, the use of multiple inhalers adds complexity to the treatment regimen, especially when considering the different types of inhalers currently available and patient preferences.Citation85

An analysis of prescribing patterns in the UK indicated that 32% of patients received triple therapy between 2002 and 2010, regardless of GOLD severity category.Citation86 Few patients in GOLD groups A, B, C, or D (as defined in the 2011 GOLD report) received triple therapy prior to or at initial diagnosis, but after initial diagnosis, prescriptions for triple therapy occurred in 19%, 28%, 37%, and 46% of patients in GOLD groups A, B, C, and D, respectively.Citation86 The most frequent treatment-escalation pathway was from ICS-LABA to triple therapy. Therefore, the majority of COPD patients may be overtreated compared with GOLD guidelines, with 75% of those receiving triple therapy having only mild or moderate COPD.Citation87,Citation88 However, it is important to note that there have been no studies to evaluate the use of aggressive treatment to reduce COPD exacerbations followed by de-escalation of the therapy. Triple therapy may allow the assumption that a patient is receiving optimal treatment for COPD with optimal bronchodilation via two mechanisms plus anti-inflammatory effects.Citation86 In addition, triple therapy does not appear to be associated with a greater risk of adverse events compared with ICS-LABA or LAMA monotherapy.Citation81,Citation84

Fluticasone furoate–umeclidinium–vilanterol inhalation powder (Trelegy Ellipta; GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) was recently approved by the FDA as the first once-daily single-inhaler triple therapy for COPD.Citation89 Combination triple therapy in a single inhaler may increase the likelihood of better adherence,Citation85 but it also increases the expense of the product in the absence of generic equivalents.Citation45 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines state that triple therapy is cost-effective only in patients who have FEV1 <50% predicted and frequent exacerbations (two or more in past 12 months).Citation86,Citation90 In this regard, it is interesting that only 2.1% of patients in the SPIROMICS cohort, of whom 30% had severe airflow obstruction, had two or more exacerbations in each year over a 3-year period.Citation91 Therefore, the frequent exacerbator phenotype appears to be much less common than reported in the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE) study.Citation92 Accurate assessment of exacerbation history and future risk is thus necessary to guide individualized therapy decisions in patients with COPD.

For patients with COPD who continue to experience exacerbations while receiving LABA-LAMA-ICS therapy, the addition of a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor or macrolide antibiotic has been recommended.Citation1 Moreover, therapeutic agents targeting eosinophils, namely anti-IL5 and anti-IL5-receptor monoclonal antibodies, have been evaluated to reduce the risk of exacerbations in COPD patients with high eosinophil counts and a history of exacerbations despite optimized standard-of-care therapy;Citation43 however, results have been inconsistent.Citation93–Citation95

Overall, the use of ICSs in dual and triple therapy for COPD has been shown to reduce exacerbations and improve symptoms. Furthermore, individualizing therapies based on each patient’s phenotype, including risk factors and comorbidities, has the potential to maximize the benefit:risk ratio of COPD treatment.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Katie Gersh, PhD of MedErgy (Yardley, PA, USA), in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and funded by AstraZeneca (Wilmington, DE, USA). AstraZeneca reviewed the manuscript for medical accuracy.

Disclosure

DPT has served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Sunovion; as a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Sunovion; and as a consultant for Theravance/Innoviva. CS has current, past, or pending grants in COPD from Adverum, the Alpha-1 Foundation, BTG, CSL Behring, Grifols, MatRx, NIH, Novartis, PneumRx, and Shire. He consults for Abeona, AstraZeneca, CSA Medical, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, and Uptake Medical on COPD. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPDBethesda (MD)GOLD2018

- SaettaMFinkelsteinRCosioMGMorphological and cellular basis for airflow limitation in smokersEur Respir J199478150515157957838

- FinkelsteinRFraserRSGhezzoHCosioMGAlveolar inflammation and its relation to emphysema in smokersAm J Respir Crit Care Med19951525 Pt 1166616727582312

- ThompsonABMuellerMBHeiresAJAerosolized beclomethasone in chronic bronchitis: improved pulmonary function and diminished airway inflammationAm Rev Respir Dis199214623893951489129

- ConfalonieriMMainardiEdella PortaRInhaled corticosteroids reduce neutrophilic bronchial inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax19985375835859797758

- PaggiaroPLDahleRBakranIFrithLHollingworthKEfthimiouJMulticentre randomised placebo-controlled trial of inhaled fluticasone propionate in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLancet199835191057737809519948

- WiseRConnettJWeinmannGScanlonPSkeansMEffect of inhaled triamcinolone on the decline in pulmonary function in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2000343261902190911136260

- PauwelsRALöfdahlC-GLaitinenLALong-term treatment with inhaled budesonide in persons with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who continue smokingN Engl J Med1999340251948195310379018

- VestboJSørensenTLangePBrixATorrePViskumKLong-term effect of inhaled budesonide in mild and moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trialLancet199935391671819182310359405

- BurgePSCalverleyPMJonesPWSpencerSAndersonJAMaslenTKRandomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of fluticasone propionate in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ISOLDE trialBMJ200032072451297130310807619

- HighlandKBStrangeCHeffnerJELong-term effects of inhaled corticosteroids on FEV1 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysisAnn Intern Med20031381296997312809453

- SorianoJBSinDDZhangXA pooled analysis of FEV1 decline in COPD patients randomized to inhaled corticosteroids or placeboChest2007131368268917356080

- AnthonisenNRConnettJEKileyJPEffects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1: the Lung Health StudyJAMA199427219149715057966841

- SinDDMcAlisterFAManSFAnthonisenNRContemporary management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: scientific reviewJAMA2003290172301231214600189

- AgarwalRAggarwalANGuptaDJindalSKInhaled corticosteroids vs placebo for preventing COPD exacerbations: a systematic review and metaregression of randomized controlled trialsChest2010137231832519783669

- YangIAClarkeMSSimEHFongKMInhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20127CD002991

- BarnesPJShapiroSDPauwelsRAChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: molecular and cellular mechanismsEur Respir J200322467268814582923

- BarnesPJImmunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseNat Rev Immunol20088318319218274560

- ChengSLSuKCWangHCPerngDWYangPCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with inhaled medium- or high-dose corticosteroids: a prospective and randomized study focusing on clinical efficacy and the risk of pneumoniaDrug Des Devel Ther20148601607

- BoardmanCChachiLGavrilaAMechanisms of glucocorticoid action and insensitivity in airways diseasePulm Pharmacol Ther201429212914325218650

- PowellHGibsonPGHigh dose versus low dose inhaled corticosteroid as initial starting dose for asthma in adults and childrenCochrane Database Syst Rev200422CD004109

- FoodUSAdministrationDrugChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: developing drugs for treatment2016 Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-20/pdf/2016-11855.pdfAccessed July 12, 2018

- UsmaniOSItoKManeechotesuwanKGlucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation in airway cells after inhaled combination therapyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005172670471215860753

- HaqueRHakimAMoodleyTInhaled long-acting β2 agonists enhance glucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation and efficacy in sputum macrophages in COPDJ Allergy Clin Immunol201313251166117324070494

- BarnesPJScientific rationale for inhaled combination therapy with long-acting β2-agonists and corticosteroidsEur Respir J200219118219111843317

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- FergusonGTAnzuetoAFeiREmmettAKnobilKKalbergCEffect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50 µg) or salmeterol (50 µg) on COPD exacerbationsRespir Med200810281099110818614347

- NanniniLJLassersonTJPoolePCombined corticosteroid and long-acting β2-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting β2-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20129CD006829

- NanniniLJPoolePMilanSJKestertonACombined corticosteroid and long-acting β2-agonist in one inhaler versus inhaled corticosteroids alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20138CD006826

- ObaYLoneNAComparative efficacy of inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta agonist combinations in preventing COPD exacerbations: a Bayesian network meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014946947924872685

- MiravitllesMD’UrzoASinghDKoblizekVPharmacological strategies to reduce exacerbation risk in COPD: a narrative reviewRespir Res201617111227613392

- CalverleyPMErikssonGJenkinsCREarly efficacy of budesonide/formoterol in patients with moderate-to-very-severe COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201712132528031707

- CalverleyPMPostmaDSAnzuetoAREarly response to inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids as a predictor of 12-month treatment responder status and COPD exacerbationsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20161138139026952309

- VogelmeierCHedererBGlaabTTiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2011364121093110321428765

- DecramerMLChapmanKRDahlROnce-daily indacaterol versus tiotropium for patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (INVIGORATE): a randomised, blinded, parallel-group studyLancet Respir Med20131752453324461613

- TrudoFKernDMDavisJRComparative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol combination and tiotropium bromide among COPD patients new to these controller treatmentsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102055206626451101

- WedzichaJACalverleyPMSeemungalTAThe prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromideAm J Respir Crit Care Med20081771192617916806

- RodrigoGJPriceDAnzuetoALABA/LAMA combinations versus LAMA monotherapy or LABA/ICS in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171290792228360514

- WedzichaJABanerjiDChapmanKRIndacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPDN Engl J Med2016374232222223427181606

- BafadhelMMcKennaSTerrySBlood eosinophils to direct corticosteroid treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121861485522447964

- SiddiquiSHGuasconiAVestboJBlood eosinophils: a biomarker of response to extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2015192452352526051430

- BafadhelMPetersonSde BlasMAPredictors of exacerbation risk and response to budesonide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post-hoc analysis of three randomised trialsLancet Respir Med20186211712629331313

- TashkinDPWechslerMERole of eosinophils in airway inflammation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20181333534929403271

- ChengSLLinCHEffectiveness using higher inhaled corticosteroid dosage in patients with COPD by different blood eosinophilic countsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016112341234827703344

- CalverleyPVliesBA rational approach to single, dual and triple therapy in COPDRespirology201621458158926611377

- WatzHTetzlaffKWoutersEFBlood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trialLancet Respir Med20164539039827066739

- PascoeSLocantoreNDransfieldMTBarnesNCPavordIDBlood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trialsLancet Respir Med20153643544225878028

- HastieATMartinezFJCurtisJLAssociation of sputum and blood eosinophil concentrations with clinical measures of COPD severity: an analysis of the SPIROMICS cohortLancet Respir Med201751295696729146301

- ChristensonSASteilingKvan den BergeMAsthma-COPD overlap: clinical relevance of genomic signatures of type 2 inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2015191775876625611785

- TamadaTSugiuraHTakahashiTBiomarker-based detection of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome in COPD populationsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102169217626491283

- AlshabanatAZafariZAlbanyanODairiMFitzgeraldJMAsthma and COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS): a systematic review and meta analysisPLoS One2015109e013606526336076

- TashkinDPMurrayRPSmoking cessation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med2009103796397419285850

- SimmonsMSConnettJENidesMASmoking reduction and the rate of decline in FEV1: results from the Lung Health StudyEur Respir J20052561011101715929955

- TamimiASerdarevicDHananiaNAThe effects of cigarette smoke on airway inflammation in asthma and COPD: therapeutic implicationsRespir Med2012106331932822196881

- HoonhorstSJten HackenNHVonkJMSteroid resistance in COPD? Overlap and differential anti-inflammatory effects in smokers and ex-smokersPLoS One201492e8744324505290

- SohalSSReidDSoltaniAChanges in airway histone deacetylase2 in smokers and COPD with inhaled corticosteroids: a randomized controlled trialPLoS One201385e6483323717666

- van OverveldFJDemkowUGóreckaDde BackerWAZielińskiJDifferences in responses upon corticosteroid therapy between smoking and non-smoking patients with COPDJ Physiol Pharmacol200657Suppl 427328217072055

- TashkinDPMurrayHESkeansMMurrayRPSkin manifestations of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD patients: results from Lung Health Study IIChest200412641123113315486373

- EichenhornMSWiseRAMadhokTCLack of long-term adverse adrenal effects from inhaled triamcinolone: Lung Health Study IIChest20031241576212853502

- CummingRGMitchellPLeederSRUse of inhaled corticosteroids and the risk of cataractsN Engl J Med199733718149203425

- WangJJRochtchinaETanAGCummingRGLeederSRMitchellPUse of inhaled and oral corticosteroids and the long-term risk of cataractOphthalmology2009116465265719243828

- MillerDPWatkinsSESampsonTDavisKJLong-term use of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol fixed-dose combination and incidence of cataracts and glaucoma among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in the UK General Practice Research DatabaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011646747622003292

- RennardSITashkinDPMcElhattanJEfficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol in one hydrofluoroalkane pressurized metered-dose inhaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a 1-year randomized controlled clinical trialDrugs200969554956519368417

- SilvaDRCoelhoACDumkeAOsteoporosis prevalence and associated factors in patients with COPD: a cross-sectional studyRespir Care201156796196821352667

- FergusonGTCalverleyPMAAndersonJAPrevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the Towards a Revolution in COPD Health studyChest200913661456146519581353

- LokeYKCavallazziRSinghSRisk of fractures with inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studiesThorax201166869970821602540

- ScanlonPDConnettJEWiseRALoss of bone density with inhaled triamcinolone in Lung Health Study IIAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004170121302130915374846

- RommeEAGeusensPLemsWFFracture prevention in COPD patients: a clinical 5-step approachRespir Res2015163225848824

- BourbeauJAaronSDBarnesNCDavisKJLacasseYNadeauGEvaluating the risk of pneumonia with inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: retrospective database studies have their limitations SARespir Med2017123949728137503

- DiSantostefanoRLSampsonTLeHVHindsDDavisKJBakerlyNDRisk of pneumonia with inhaled corticosteroid versus long-acting bronchodilator regimens in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a new-user cohort studyPLoS One201495e9714924878543

- SinghSAminAVLokeYKLong-term use of inhaled corticosteroids and the risk of pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysisArch Intern Med2009169321922919204211

- SinDDTashkinDZhangXBudesonide and the risk of pneumonia: a meta-analysis of individual patient dataLancet2009374969171271919716963

- JansonCLarssonKLisspersKHPneumonia and pneumonia related mortality in patients with COPD treated with fixed combinations of inhaled corticosteroid and long acting β2 agonist: observational matched cohort study (PATHOS)BMJ2013346f330623719639

- MorjariaJBRigbyAMoriceAHInhaled corticosteroid use and the risk of pneumonia and COPD exacerbations in the UPLIFT studyLung2017195328128828255905

- KewKMSeniukovichAInhaled steroids and risk of pneumonia for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD010115

- JansonCStratelisGMiller-LarssonAHarrisonTWLarssonKScientific rationale for the possible inhaled corticosteroid intraclass difference in the risk of pneumonia in COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017123055306429089754

- YangHHLaiCCWangYHSevere exacerbation and pneumonia in COPD patients treated with fixed combinations of inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β2 agonistInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017122477248528860742

- SinghDMiravitllesMVogelmeierCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease individualized therapy: tailored approach to symptom managementAdv Ther201734228129927981495

- MagnussenHDisseBRodriguez-RoisinRWithdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2014371141285129425196117

- RossiAGuerrieroMCorradoAWithdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO)Respir Res2014157725005873

- SinghDPapiACorradiMSingle inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting β2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trialLancet20163881004896397327598678

- LipsonDABarnacleHBirkRFULFIL trial: once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017196443844628375647

- LipsonDABarnhartFBrealeyNOnce-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPDN Engl J Med2018378181671168029668352

- KwakMSKimEJangEJKimHJLeeCHThe efficacy and safety of triple inhaled treatment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis using Bayesian methodsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102365237626604734

- MäkeläMJBackerVHedegaardMLarssonKAdherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPDRespir Med2013107101481149023643487

- BrusselleGPriceDGruffydd-JonesKThe inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UKInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102207221726527869

- SimeoneJCLuthraRKailaSInitiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the USInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201712738328053518

- ManninoDYuTCZhouHHiguchiKEffects of GOLD-adherent prescribing on COPD symptom burden, exacerbations, and health care utilization in a real-world settingChronic Obstr Pulm Dis20152322323528848845

- Trelegy Ellipta (fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol inhalation powder) [package insert]Research Triangle Park (NC)GlaxoSmithKline2017

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Management of Adults With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Primary and Secondary CareLondonNICE2009

- HanMKQuibreraPMCarrettaEEFrequency of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an analysis of the SPIROMICS cohortLancet Respir Med20175861962628668356

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- PavordIDChanezPCrinerGJMepolizumab for eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2017377171613162928893134

- AstraZenecaAstraZeneca provides update on GALATHEA Phase III trial for Fasenra in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [press release]2018511 Available from: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2018/astrazeneca-provides-update-on-galathea-phase-iii-trial-for-fasenra-in-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-11052018.htmlAccessed July 12, 2018

- AstraZenecaUpdate on TERRANOVA Phase III trial for Fasenra in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [press release]2018530 Available from: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2018/update-on-terranova-phase-iii-trial-for-fasenra-in-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-30052018.htmlAccessed July 12, 2018